“No one else could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you. I am now going to shut it.”

—The Doorkeeper, “Before the Law,” Franz Kafka (Trans. Willa & Edwin Muir)[1]

In one of Kafka’s most renowned short works, he tells the story of a man from the country who seeks admittance to the Law through a gate watched by a doorkeeper; the doorkeeper tells him that he could gain entry, but not now, so he patiently waits for years, never to gain admittance. As he is dying, he asks the doorkeeper why, in all those years, no one else has ever come to ask for admittance to the Law, at which point the doorkeeper utters the above epigraph.[2]

Kafka saw this story published during his lifetime and later wove it into his novel The Trial as part of a dialogue between the main character, K, and a prison chaplain—a dialogue that makes clear that Kafka knew just how torturously ripe for interpretation this parable is. It’s the one part of Kafka that’s stuck in my head ever since my high school English and German courses, and I’ve come to think it’s gotten lodged there because my life with video games has called “Before the Law” back to me time and time again.

“Before the Law” is like a koan: it presents a scenario that feels paradoxical to the reader and is, therefore, hard to understand intuitively.[3] The interpretations discussed in The Trial underscore this: did the doorkeeper deceive the man from the country? Was the doorkeeper himself deceived by his servitude to the law? Why doesn’t the man cross the gate’s threshold if this passage to the Law if that gate was meant for him alone?

I won’t attempt to dissolve the koan here: instead, I want to show you how particular elements of Kafka’s parable map to particular aspects of video-game stories in ways Kafka couldn’t have anticipated, giving us both a new way to think about the source text and a new set of koans through which to meditate on our experiences in gaming. By the same token, I hope that you will read this not as a contribution to theory, but rather as a perspective that might afford a different way of contemplating and discussing the marvelous puzzles of video-game storytelling that serve as such fruitful focal points of theorizing.

(Note that this article discusses plot details of Dark Souls, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, The Stanley Parable, Xenoblade Chronicles (1), Final Fantasy XV, The Monster at the End of This Book, Undertale, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, Dark Souls II, Elden Ring, and Maquette. People have different definitions of “spoilers,” but I would personally say that only Majora’s Mask, The Stanley Parable, The Monster at the End of This Book, and Maquette are discussed in ways that “spoil” aspects of the plot rather than mentioning something less consequential in passing.)

The Telic Dissonance of Video-Game Objects

“This gate was made only for you.”

One of the metaphysically unsettling aspects of “Before the Law” is the fact that we’re meant to understand a specific object—in this case, the first gate of several granting access to the Law—as something that is meant to be used by a specific person yet apparently unavailable for that person’s use.

In the modern world, we typically don’t think of most natural (i.e. not man-made) objects as existing for a specific end—or having what Aristotle and other philosophers refer to as a telos (a goal in virtue of which it exists)—that essentially refers to a particular person’s use of that object: it is possible for Aaron Suduiko to chop down a tree and use its lumber for firewood, but it doesn’t follow from this fact that the tree exists in order for Aaron Suduiko to use it as firewood. In games, on the other hand—not just video-game stories, but rather games more broadly—we’re accustomed to objects existing within the game by virtue of satisfying a specific end related to a player of that game: in chess, for instance, an object exists as a knight by virtue of being something that the player is able to move in an L-shaped diagonal during a game.[4]

The object I’m holding here exists within the game of chess as a knight by virtue of being something I am able to move in an L-shaped diagonal during a game. (Photograph by Aaron Suduiko.)

In the stories of video games, we get an unnerving blend of these two cases: natural objects within the fiction of a video game are typically meant to appear as ordinary objects (like our tree example) within the context of the avatar’s experience, yet within the context of the player’s experience, such objects typically have a telos that essentially refers to the avatar and player’s use of them—a tree within a game like Breath of the Wild may really “exist” in this second sense for the purpose of the player’s being able to have Link, her avatar, chop it down. We can call this uncomfortable juxtaposition of different perspectives on objects within video-game fictions telic dissonance.

We don’t always realize it, but, because of this telic dissonance, video-game stories demand of us a kind of “double sight” when we play them: we simultaneously view them as naturalistic worlds in order to make sense of the avatar’s place in the story, and as worlds where every object is just waiting for us to find and use it for its specific purpose, the purpose according to which it was “made only for you.”

The telic dissonance of video-game-story objects requires us to have a “double sight” as players: we see trees Link encounters as ordinary natural objects Link is encountering, yet also as objects that were designed for us to use in a particular way (e.g., as firewood for Link).

We don’t always realize this because the stories of video games are often structured such that our objectives naturally align with what it might make sense for the avatar to do; for this reason, there typically isn’t a perceived dissonance between our intended ends and “moves” as players of a game and what avatars, as characters within a fiction, would happen to do within a naturalistic world regardless of a narrative arc.[5] But this needn’t be the case, and it’s in moments in which our aims diverge from the natural order of the fictionally represented world that Kafka looms large.

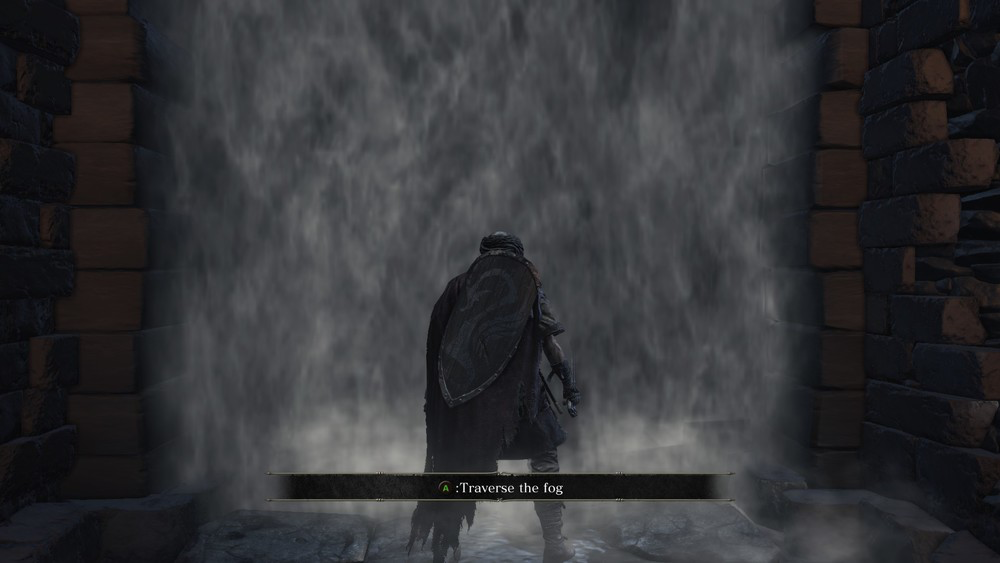

Stop and meditate on the final approach to Ornstein and Smough in Anor Londo in Dark Souls, or the approach to your favorite “Boss Door” in another video game. There are natural explanations within the fiction for why the bosses are there, why the avatar needs to fight them, and where each of these entities came from—but it’s also true that, as players, our best prima facie explanation of what’s going on at this moment is that Ornstein and Smough are simply in Anor Londo’s main chambers, holding vigil in front of the illusory Gwynevere’s alcove, waiting for us to arrive.[6] We press our buttons to make our avatar approach the fog wall and traverse the white light, peering through to the other side:

“the man stoops to peer through the gateway into the interior. Observing that, the doorkeeper laughs and says: ‘If you are so drawn to it, just try to go in despite my veto. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the least of the doorkeepers. From hall to hall there is one doorkeeper after another, each more powerful than the last. The third doorkeeper is already so terrible that even I cannot bear to look at him.’”

It’s moments like this that turn video-game stories into a pressing puzzle, but this is also how they blossom into complex stories that couldn’t be told in another medium such as Kafka’s written word. The bizarre paradox of Mikau existing in an unresolved state between life and death until Link’s arrival is precisely what points the way to a radical kind of solipsism—and, ultimately, radical freedom—in reading The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Games that make thematic meaning out of this telic dissonance can color the reading experience in hues unavailable to other media, whether that’s the hue of guilt in Silent Hill 2, the hue of nostalgia overcoming cynicism in Ni No Kuni, or the hue of empowerment as the consumer of a narrative in Elden Ring.

3 Meditations

With this peculiarity of video-game worlds in view, we can dissect Kafka’s parable into three distinct objects of meditation for gamers: imagining the man from the country as the avatar, and meditating on either (1) his plight or (2) the plight of the player; or, (3) imagining and meditating on the man from the country as the player.

Meditation 1: Before the Fog Wall

Before the Law stands a boss. To this boss there comes an avatar and prays for admittance to the Law. But the boss says that he cannot grant admittance at this moment.

Link standing before Odolwa in The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask 3D.

From its very first phrase onward, Kafka’s parable is metaphysical: it’s not clear what “the Law” is, such that someone could physically stand before it or gain admittance to it. There’s a metaphysical analogue in the case of avatar confronting boss: although most literally, a boss typically stands before some kind of item or desired concrete objective, there’s also something quite “Law-like” to which bosses block an avatar’s access: a promised meaning to life.

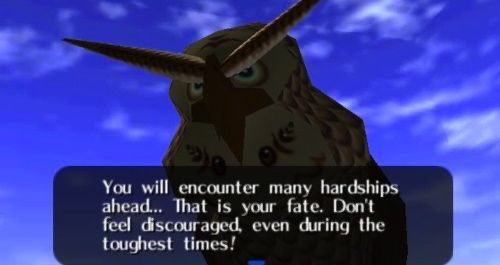

Ask yourself why, within the context of your favorite video-game fiction, the avatar would choose to proceed along the game’s plot, and the typical answer is that they are offered some explanation of how the events constituting this plot afford them a special opportunity to bring about, or participate in, a sort of meaning that couldn’t be realized otherwise. Kaepora Gaebora lays out for Link the world’s need for a hero in both Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask (albeit with antithetical connotations); Dark Souls calls a Chosen Undead to rekindle a dying fire; James has an opportunity to answer a letter that never should have been sent in Silent Hill 2.

What we aren’t saying is that the avatar is fighting in order to proceed along the game’s story: remember, the point of this meditation is to consider the situation from the perspective of the avatar, and the typical video game (contra an overtly self-aware fiction like The Stanley Parable[7]) doesn’t represent its avatar as aware of the fact that it is an avatar playing a role within a work of fiction. We might imagine in some cases that avatars are presented with opportunities to tell a certain “story of their lives” by virtue of enacting the events that constitute the plot—imagining, for instance, that Link is able to tell a story about himself whereby he becomes a hero by acquiescing to Kaepora Gaebora and becoming the Hero of Time (not unlike we construct narratives by which to understand our own, real lives)—but, both because it’s more generally applicable and because it avoids ambiguity with the self-aware case considered above, I prefer to consider the “Law” in this meditation as some kind of promised meaning for the avatar’s life.[8]

Like a normative law—whether that be a law governing legally permissible conduct, morally permissible conduct, or socially permissible conduct—a promised meaning to life offers certain advantages to those who elect to be governed by that law’s prescriptions for their conduct. The avatar who chooses to enact the events constituting the game’s plot is afforded the advantage of special meaning, whether that’s becoming a hero, coming to understand its own identity, or simply finding a place in the world that wouldn’t otherwise be available to it. Many strive to earn this privilege: Dark Souls, Bloodborne, and Elden Ring are littered with NPCs who were charged with the same quest designated for the avatar, only to have failed or given up; even Skull Kid may be read as someone desperately seeking the agency afforded Link, only to be denied it.[9] For that meaning, though it seems like the kind of thing that ought to be accessible by anyone within the avatar’s world, was made only for the avatar: though the avatar (typically) has no reason to know it, there is a metaphysically real sense in which this path and kind of meaning is uniquely designed for the avatar, not NPCs (this being a recapitulation of the telic dissonance I defined in the previous section).

Yet it’s necessary to this kind of meaning that it must be seized, not happened upon. Its doorkeepers are existentially precarious in the way that Kafka’s doorkeeper is: as Kafka articulates in The Trial (through the mouthpiece of a prison chaplain who is discussing various interpretations of the parable with the novel’s protagonist, K), the doorkeeper seems to be subordinate to the man from the country despite barring his entry to the Law:

Now the man from the country is really free, can go where he likes, it is only the Law that is closed to him […] But the doorkeeper is bound to his post by his very office, he does not dare go out into the country, nor apparently may he go into the interior of the Law, even should he wish to. […] One must assume that for many years, for as long as it takes a man to grow up into the prime of his life, his service was in a sense an empty formality, since he had to wait for a man to come, that is to say someone in the prime of life, and so he had to wait a long time before the purpose of his service could be fulfilled, and, moreover, had to wait on the man’s pleasure, for the man came of his own free will.[10]

The boss exists as a finite link in the chain of progress servicing the avatar’s quest for a specific meaning; it challenges the avatar, only to be overcome. Its existence is an empty formality until the avatar arrives, and is often trivialized in an unexpectedly comic way afterward by turning the boss into a commodity, be it a Boss Weapon (the pathos of Artorias transposed into a sword in Dark Souls), a memento (Odolwa transposed into portable remains in Majora’s Mask), or an object through which the avatar can further focalize its own identity (the reward of a cinematic cutscene illuminating Shulk’s character more than the boss’s in Xenoblade Chronicles).

Yet even with the boss bound to this fate of servitude, the avatar sits in existential discomfort. Why must the avatar persist in the face of being denied access to the Law? Particularly in video-game fictions where bosses are unavoidably challenging, this is a psychically vexing tension for avatar and player alike. Why is it so unpalatable to imagine the Chosen Undead settling in Undead Burg, or the Firelink Shrine, rather than plunging to its death in Sen’s Fortress again and again for the sake of a quest that denies them entry?

One of the joys of watching video-game stories innovate is getting to watch them fill out the world around this parable of avatar and boss threshold in a range of different ways. Particularly relevant here is the diverse family of games collectively called “open world” in one sense or another, unified by the sense that there are intrinsically meaningful paths for the avatar to take in the world that are orthogonal to all series of events that advance the game from its beginning to a state in which the end credits roll. What does it mean when the man from the country finds himself before the Law in a game like Breath of the Wild or Final Fantasy XV? When there exist more things to do outside the Law than within it, does it remain the case that “Everyone strives to reach the Law?” I personally know people who reflectively elect not to defeat the final bosses of games like this, in order that they and their avatars might continue to have adventures within that fiction for a long time still to come.

Yet from the avatar’s perspective, is it really possible to be happy refusing the call of destiny? Could we even take Noctis seriously as a competent agent if he fully recognized the onus on him to save the world, yet soberly chose to go on drives and mercenary adventures with his friends ad infinitum instead of fulfilling that duty?[11]

Meditation 2: Before the Boss

“[The man from the country] decides that it is better to wait until he gets permission to enter. The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down at one side of the door. There he sits for days and years. He makes many attempts to be admitted, and wearies the doorkeeper by his importunity.”

The middle section of Kafka’s parable presents a puzzle of motive: why does the man, free as he is, elect to spend a lifetime waiting for admittance to the Law, rather than either walking away or trying to gain access regardless of the doorkeeper’s admonition?

Imagining the man from the country as an avatar gives us a new way to schematize this puzzle: instead of the man’s motive being opaque to us, the man’s motive is now relocated to the player. By meditating on the player’s position before the boss, we contemplate what it means to push onward in a story that both needs and rebukes our involvement.

Nowhere is this meditation more illuminating than in one of the original video games, which turned a whopping 50 years old last year:

The cover of one of the oldest video games in the world. This is also the appropriate time to cover the “Compares Sesame Street with Kafka” square on your Bingo sheet for this article. (Source.)

In many regards, The Monster at the End of This Book shows just as much (if not more) nuance as many modern video games in how it treats the sort of player-avatar relationships that pertain to our current meditations.[12] The conceit of the book is that Sesame Street’s Grover greets the reader on the book’s cover, notices the name of the book, becomes scared of the monster waiting at the book’s conclusion, and begs the reader to stop turning pages—going so far as to place illustrated “obstacles” in their way intended to prevent them from turning pages, which obviously do nothing to actually prevent a child or her parent from turning to the next page. Thankfully for Grover, by the time he and the reader arrive at the end of the book, he realizes that the title referred to Grover’s own presence at the end of the book.

This book is a beloved childhood memory for many, myself included (I could not even begin to estimate the number of times I made my dad mimic Grover’s voice as I “played the game” by turning pages despite Grover’s protestations). It’s also a book featuring a protagonist that’s something like an avatar and something like a boss: he rejects his own role in the promised meaning of the story (at least, the role as he conceives of it) and seeks to prevent the reader from “playing the game” at all, asking the reader to abstain from bringing about his “fated outcome” within the fiction (prefiguring, in this regard, Toby Fox’s similar call to abstention in Undertale, 44 years later). This story is, therefore, a good path into contemplating the kind of authority and mentality the player really has when her avatar stands before the boss.

Grover is powerless to stop the reader from turning the page because he and the reader exist on different levels of the fiction: although the reader participates in the fiction, she does so through a physical medium (the actual matter of the book) which Grover’s illustrated obstacles can’t influence, by virtue of being bound within the individual, static pages of the book.[13] This may seem like an obvious point to dissect, but it points the way to a similar kind of powerlessness arising from a difference in fictional level in the case of video games: as we discussed earlier, video-game objects are “made only for” players in a fundamentally different, telic way than they are for avatars, meaning that the considerations which objects within the game raise for the avatar don’t exhaust, nor even necessarily exist within, the set of considerations which those objects raise for the player in making decisions within the game. Like Grover, the avatar may desperately want something that is within the player’s power to effect (like a disengagement from the quest for a promised meaning), yet those desires, like Grover’s makeshift obstacles, aren’t always the right kind of thing to motivate the player.

This divergence in player motive and avatar motive can cut both ways, either keeping the man from the country before the Law when he’d rather leave or insisting that he go elsewhere when he’d really rather beg admittance to the Law.[14]

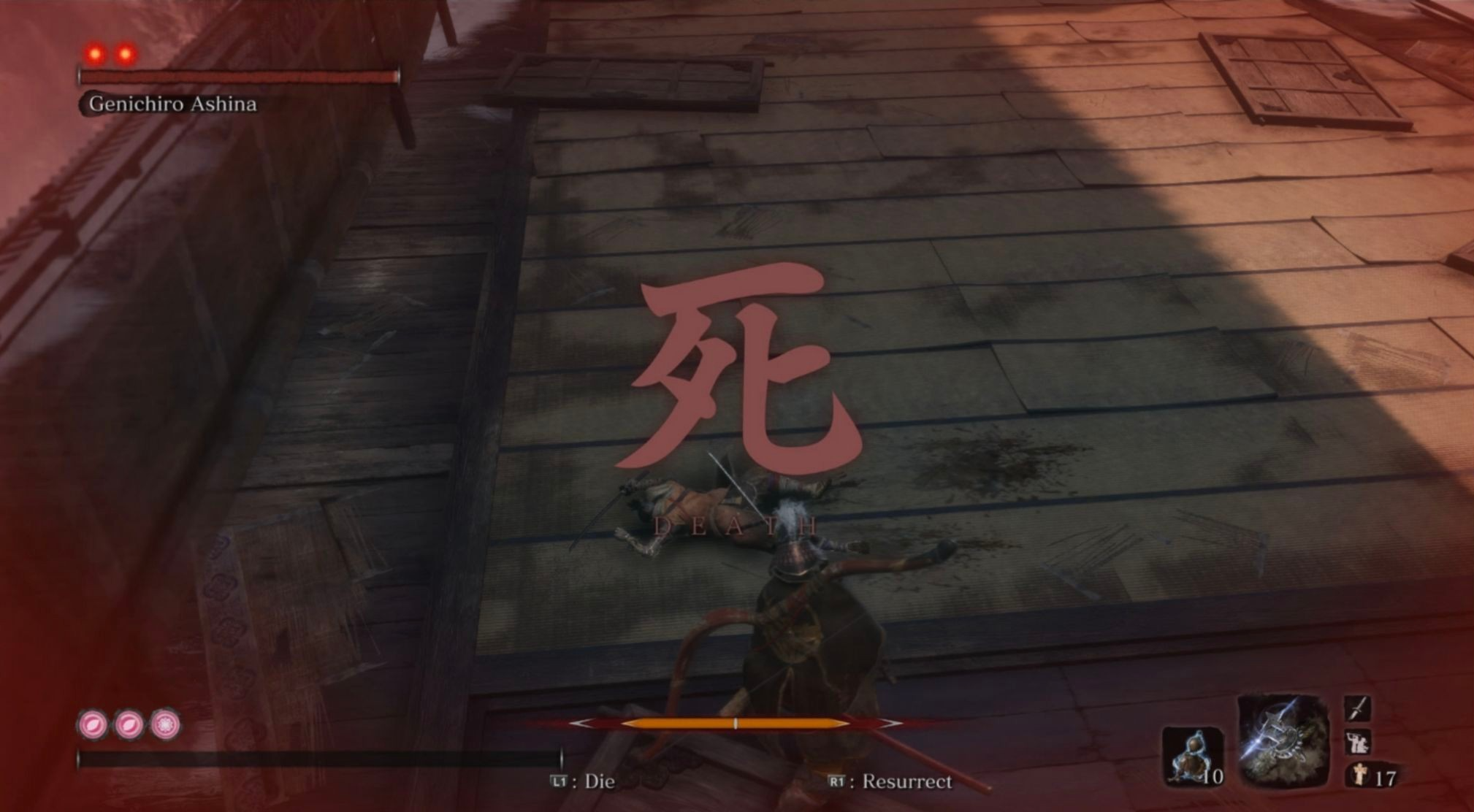

Imagine a case like trying and failing again and again to make Wolf victorious over Genichiro Ashina in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice (an experience that demonstrates how much more effort can be required to “turn the page” in a video game as opposed to in The Monster at the End of This Book). Genichiro Ashina stands at the vanguard of doorkeepers in the case of Sekiro’s Law: none of the promised meanings for Wolf’s life—nor any of the promised narrative satisfaction, from the perspective of the player—are accessible without defeating him, yet he is also considered to be the first boss that challenges the player’s technical prowess to the full extent that the game routinely demands thereafter. As the player and avatar are repeatedly denied passage over this threshold to the Law, we can imagine and meditate on 4 distinct possible outcomes:

- Wolf feels driven to push on and continue trying for the sake of his mission (and, more specifically, for the sake of his lord, Kuro), but the player is enervated by her many failures, refusing to continue seeking access to the Law despite the man’s desires to the contrary.

- Wolf is beaten down from his many failures and ready to submit, similar to the state in which he’s found at the beginning of the game, but the player—resolutely? masochistically? incorrigibly?—insists on trying again and again and again, keeping the man from the country before the Law for days, months, years.

- Wolf and the player both fight on steadfastly.

- Wolf and the player both submit, their wills jointly broken.

Outcomes [3] and [4] are certainly conceivable, but they aren’t interesting for the purpose of this meditation: the point here is that there’s nothing in the structure of video-game fictions to rule out outcomes [1] and [2] prima facie, and in those outcomes manifests the divergence of player-avatar motives in a way that casts the man’s inertia before the Law in a new light.

The avatar’s whole raison d’être may seem bound up with the meaning promised to it by the plot, but there’s no reason to suppose we must extend that feeling of bondage to the player: as the reader of The Monster at the End of This Book can happily turn its pages with blatant disregard for Grover, so, too, can the player elect to ignore the avatar’s quest and instead pursue those options that seemed so “unpalatable” for the avatar in our previous meditation. The player can spend time enjoying the ambiance of Undead Burg even if it does violence to the concept of a “Chosen Undead” for her avatar to do so; the player can elect to go sightseeing and enjoy the atmosphere in a way that may cut against the grain of a battle-hardened avatar’s constant struggle; the player can even partake in an excessive “grind,” having the avatar slaughter countless more enemies than may be warranted by its quest, for any number of reasons.

And indeed, these aren’t mere conceptual possibilities: as players, many of us have made these behavioral patterns a part of how we play games, or what some might call different “metagames” that we play within a game when we aren’t directly engaging with its plot. While there may not be much fan sentiment toward Undead Burg, there is a cottage industry of memes celebrating the quiet, distant comfort of Dark Souls II’s Majula (here is one of my favorites, and here’s another). I still remember my surprise when Nathan Randall first stopped paused in the middle of a new Dark Souls title to simply look around and appreciate the breathtaking landscape; then, I found myself (and the rest of the community) doing the exact same thing upon discovering the starry underground wonderland of Nokron for the first time in Elden Ring (below). I’ve watched in awe as Dan Hughes has ground out more levels on his Elden Ring characters than any content in the game could possibly require, just for the pleasure he took in it.

To contemplate this second meditation on “Before the Law,” therefore, is to confront an aspect of our psychology as players. We have the option to guide the avatar in a way unavailable to Grover’s readers: orthogonally to the plot and the architecture of its promised meaning. To do so may be natural from the perspective of acting on our own motives, but it distances the avatar from its quest without divorcing it from that quest: taking Link on mushroom-foraging adventures doesn’t sever the expectations Princess Zelda has put upon him, leaving the man from the country in an irrational yet explicable position of spending his existence bound to this gate that was meant only for him, despite never passing through it.

Meditation 3: Before the Author

In our first two meditations, we made sense of the man from the country through the lens of video games by analyzing the telic dissonance of the video-game fiction’s content as it pertains to the avatar versus the player: it’s that dissonance that places the avatar in a different existential relation to the Law than the player, highlighting the parable’s components in a way that allows us to puzzle over specific aspects of what it is to play a video-game story. But there’s a third meditation that allows us to put ourselves as players in a position epistemically closer to the avatar’s place in the first meditation, giving us a more complete picture of the forces pulling us in opposing directions every time we wrestle with a game: we must put ourselves in the place of the man from the country, and we must put the game’s creative source in the doorman’s place.

This is a more abstract and ephemeral analogy than we applied in our previous meditations, but I think that’s precisely why, for me, it drives more directly to the heart of what’s at stake for many of us players when we sit down to play a game with a story in which we are invested. For, try as we might to avoid it, we’re easily tempted into obsessing over what the ultimate “Meaning of the Game” is. This might take many forms:

- Maybe we ask what the game is “‘About’ with a capital ‘A’”

- Maybe we seek a single interpretation to make sense of the totality of our personal experiences with the game

- Maybe we try to divine a singular message that we believe the creators of the game were trying to express through the artwork

Here we have a basis for the Law in this third meditation: whereas the avatar qua man from the country sought admittance to a promised meaning for its life in our first meditation, the player qua man from the country seeks admittance to a promised meaning for her experiences within the video game’s fiction. Structurally, we might think that a similar pursuit arises in non-gaming storytelling media—for instance, when we read a novel or watch a film—but I think that the interactive component of game stories colors this case in a way that resonates with the avatar’s plight in Meditation 1. Because video games are interactive, I think that many of us feel the desire for a framework to give our actions some kind of higher meaning—just as we seek to impose a narrative upon our own real lives, or indeed as the avatar qua man from the country seeks in its own fictional life.

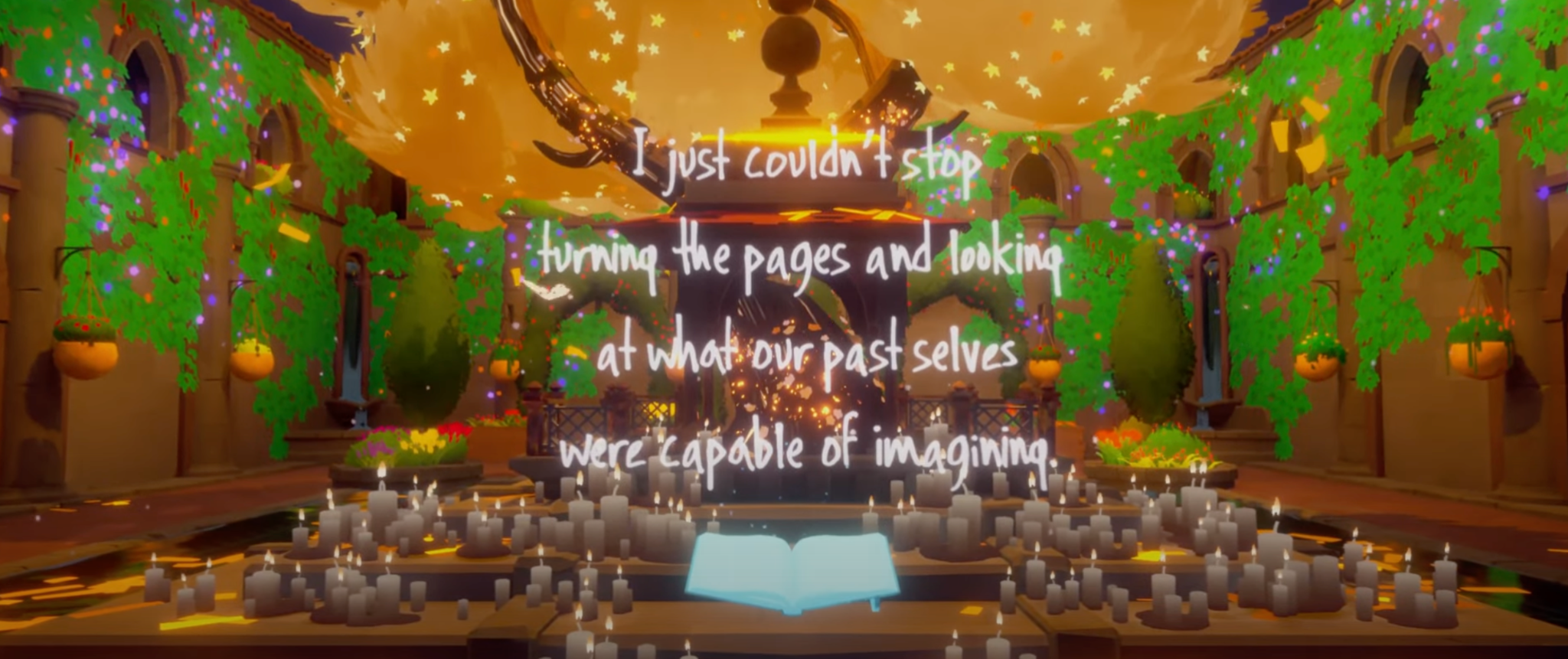

The doorkeeper—promising the player the possibility of access to this Meaning of the Game, yet barring her admittance to it—is a complex and variable entity, ultimately just whatever entity we want to interpolate in order to personify, within the fiction, the creative force that brought about this story and presents it to the player as something worth experiencing by virtue of conferring a certain meaning upon her. Maybe this is an idealized, fictional representation of the game’s flesh-and-blood creator, if it’s a game that feels as though it were crafted by an auteur (“What was Yoko Taro trying to say with NieR?”). Maybe this is a narrative voice within the fiction that seems to be focused more on framing the overall story for the player than on motivating the actions of the avatar. Recent years in gaming have been rich with incisive examples of this sort of narrator; some of my favorite examples are The Beginner’s Guide, Elden Ring, and the recent—and, in my view, criminally underappreciated—Maquette (above).

Maquette invites the player into a reflection on how a relationship began, bloomed, fell apart, and healed. It’s tense with a pathos that captures the essence of our third meditation: the player excavates the relationship between Michael and Kenzie, in partnership with an avatar that silently explores an abstract world, inspired by Michael and Kenzie’s sketchbook, from a first-person perspective, led along the journey by non-voiced writing that appears throughout the world, as though the writer were speaking to the avatar and working through the journey alongside it.

Grounded in this structure, the game manages to take the player through the entire relationship without ever clarifying whether the avatar is Michael or Kenzie, nor which of them is writing the text throughout the world. It’s even conceivable that the identities of these entities switch off, given the fact that the world is inspired by the sketchbook the two of them “would take turns drawing in.” The player enters the game with little orientation, looking to grasp a story in the writing on the wall in order to find some firm footing with which to navigate the world. But just like the world’s puzzles of perspective and physics, the narrative voice slips through the player’s fingers: what the player wants to be told to her as a regimented “Meaning of the Game” is, in fact, a conversation between two people without clear boundaries or distinction between each other in the world.

In my mind, it’s hard to imagine a better metaphor for a relationship, especially one that’s analyzed after it’s ended: you want to be able to tell yourself the whole story of what happened in the relationship and what caused it to end, but it’s impossible for you to do that because the meaning-making in a relationship is a fundamentally collaborative activity. There is no fixed meaning, but rather a conversation of meanings between two storytellers.

It’s like this when The Trial illustrates that the doorkeeper, for all his apparent authority, is at the mercy of the man’s freedom. It’s like this when we seek admittance to a game’s own framework of narrative meaning, when the interactivity of the work demands that we make choices based on maxims of our own. When we ask the doorman, “Everyone strives to reach the Law […] so how does it happen that for all these many years no one but myself has ever begged for admittance?”, the answer comes: only we can pass through this gate to it, because the game’s meaning cannot be divorced from a player’s experience with it.

This article was made only for you. I am now going to delete it.

“Before the Law” evokes the kind of esotericism that we intuitively feel even if we don’t always put a name to it. As we travel with avatars through the worlds and gates of video-game fictions, Kafka presses against the back of our mind, troubling the water with the unavoidable tensions between player and avatar, plot and freedom, bosses and monsters. Far from making games unplayable, these are the tensions that pull us back to games old and new, finding meaning in the least scrutable corners.

I think these tensions explain why we reach so readily toward metaphysics in our efforts to understand video-game stories where we wouldn’t be so inclined when considering a novel or film. I’ve previously described my own approach to video-game-story analysis as “metaphysics-first,”[15] but I think this need strikes players even as they sit and play games pre-theoretically: we recognize that the objects in game worlds are meant for us, yet also meant for us to imagine as not meant for us, and our brain needs to resolve this tension—reaching for rules within the fictional world that reach beyond that world’s physical constituents and establish “laws” governing how our interactions relate to those constituents.

We are hounded by the urge to understand the video game, a form which, at least as far as “Before the Law” goes, may be the most Kafkaesque storytelling medium to date.

The cover of the Fischer Verlag 1990 German edition of Amerika, Franz Kafka; Illustration by Franz Kafka. (Source.)

- In Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories, Franz Kafka, Ed. Nahum N. Glatzer. New York: Schocken Books, Inc., 1971, pp. 3-4. Quotations throughout refer to this citation except where otherwise noted. ↑

- The original parable is all of 591 words and bears reading in full, both with respect to this reflection and with respect to life generally. The story is available online in full as a part of Project Gutenberg here, as part of their publication of The Trial, Chapter 9 (see history below in the main text). ↑

- Dan Hughes and I discuss the interaction of game stories and koans more broadly in our recent lecture on the Final Fantasy VII series at PAX West 2022. ↑

- The two cases collapse if a person decides to “play a game” using natural objects: for instance, a tree would exist within the “game” of someone competing with someone else to see who could amass the most firewood by virtue of being something the player could chop down in order to amass firewood. But we don’t see natural objects as having this use-oriented telos unless we subordinate them within a game in this sense. ↑

- Telic dissonance is of a different kind than the popular game-studies term ‘ludonarrative dissonance’. As Richard Nguyen outlines in his “What Game Development Can Learn from Filmmaking,” ‘ludonarrative dissonance’ now traditionally refers to cases in which the story of a game implies the availability or prohibition of certain actions in a way that conflicts with the actions that are actually available to, or required of, the player (e.g., a game with a pacifism-oriented story and gameplay that requires a certain amount of killing in order to complete the story). The dissonance I have in mind is that between the avatar’s naturalistic relationship to its world and that world’s telic relationship to us as players. To see that these two concepts of dissonance are not coextensive, consider: there is no obvious sense in which Dark Souls (discussed immediately below in the main text) suffers from ludonarrative dissonance, yet it exemplifies the more Kafkaesque, telic dissonance I have defined in this section. ↑

- Like every great nuance of video-game storytelling, this motif—I learned while researching this study—has inspired charming jokes, such as Crispy Parsnips’ “Beyond the Fog Gate,” a comic strip “exploring exactly what every Soulsborne boss is doing before you get to them.” ↑

- And even in this, the most seemingly “obvious” case, it’s unclear to me whether the game’s avatar is really self-aware in the sense required by our argument. For The Stanley Parable to count as a game in which the avatar can contemplate its progression along the story of a game, the avatar must be aware of the fact that it is an avatar. The Stanley Parable feels “meta” because of the presence of a narrator that responds to the player’s choices and becomes frustrated by divergences from the narrated plot, but so far as I am aware (and I haven’t yet played the Ulta Deluxe edition of game), there is no content within the game to strongly suggest that we, as players, are supposed to ascribe to Stanley, our avatar, the (fictional) mental state of believing that he is an avatar within a video game. It may, therefore, be a reasonable explanation to instead suppose that we, as players, are choosing to make decisions that take our avatar away from the plot, while Stanley, within the fiction, experiences mental states such as desiring to go for a walk around his office, or desiring to follow a yellow line painted on the ground, with no reference to a belief that he is a character intended to follow a plot. The fact that the narrator, in one possible outcome, responds to the player’s stubborn incorrigibility by acknowledging “You are not Stanley!” reinforces the idea that most of what we consider “meta” about The Stanley Parable happens on the level of a dialectic between the narrator and the player, leaving Stanley epistemically untouched—in which case, even the seeming paragon of metafictional video-game storytelling wouldn’t be a counterexample here. ↑

- Note that, by the same reasoning, the avatar, from its perspective, would not conceive of a boss as a ‘boss’ in the sense of the term that refers to a character serving as a certain kind of gameplay obstacle within a story: the avatar, presumably, would simply see the boss, most generically, as some kind of antagonistic entity within the world. I use the term ‘boss’ in this meditation for the same reason as I use the term ‘avatar’: while these entities wouldn’t ascribe these terms to themselves, it gives us the clearest handle on the objects of our current meditation. ↑

- For those familiar with my own reading of Majora’s Mask, this is a gloss of my argument that Skull Kid needs to trick Link into playing a game in order for Skull Kid to cure his own loneliness through the player’s agency, to which only Link has direct access. ↑

- The Trial, Franz Kafka, Trans. Willa & Edwin Muir, Rev. by E. M. Butler. New York: Schocken Books, 1968, pp. 218-219. ↑

- As I discuss in my automaton reading of Breath of the Wild, one of the favorable consequences of that particular theory of mine is precisely that it provides an unusual path out of this challenge to favoring world-exploration over plot-completion in open-world games: by making the game’s avatar the kind of thing that is solely a conduit for the player’s will, the game also makes it plausible within the fiction that the avatar could elect to ignore Zelda and simply go on adventures forever instead. Notice, though, that in the context of this meditation, this kind of “solution” is no solution at all: it simply reduces the avatar’s point of view to that of the player, whereas the purpose of this meditation just is to contemplate Kafka’s parable from the perspective of an avatar. ↑

- The Monster at the End of This Book,: Starring Lovable, Furry Old Grover. Jon Stone, Ill. Michael Smolin. New York: Little Golden Books, 1971. ↑

- A full analysis of this phenomenon would require defining these distinct “levels” of fictional representation and their relations to each other, which would take us beyond the scope of this meditation. In the case of video-game stories, I have done this work elsewhere. ↑

- This is another case (cf. Fn. 5, above) where it is tempting to identify a tension I’m articulating with ‘ludonarrative dissonance’; as in the previous case, I think what we’re exploring here is conceptually distinct, but the territory is less clear-cut. The “divergence” I discuss in the main text consists in the playing the game from motives that conflict with those we would naturally attribute to the avatar, whereas ‘ludonarrative dissonance’ typically refers to a contradiction between the actions that the game’s fiction suggests the avatar should be able, required, or unable to do, and the actions that the player must actually make it the case that the avatar executes in order to progress through the story. A case in which a player is motivated to do something the avatar doesn’t want strikes me as a different sort of dissonance. The case of Dark Souls works here, just as it did in Fn. 5: it’s possible that the player of Dark Souls might get involved in activities like grinding, sightseeing, and masochism in ways that do not intuitively map to the psychology of the Chosen Undead, but this dissonance is caused by the player’s choices rather than limits imposed by the designers upon what is possible within the game (which I take to typically be responsible for ‘ludonarrative dissonance’). This strikes me as an important distinction of cause because player motivation is a distinct factor in the storytelling of video games, but I recognize that the effect of the dissonance I’m defining here may be very similar to that of ludonarrative dissonance—a similarity which may warrant a more thoroughgoing taxonomy of game-narrative tensions in the future. ↑

- The relevant citations are in my two-part study of open- vs. closed-world storytelling. In the first part, “Why It’s a Good Thing That Dark Souls Isn’t Coming Back,” I close by observing: “I’ve always seen the metaphysics of game worlds as central to understanding games’ stories, and games that specify their worlds’ metaphysics tend to tell a story about that entire world. That’s exactly the kind of story that’s a prime candidate for closed storytelling [(i.e. the creation of a story where no aspect of the plot is left unresolved, and so there is nothing about the story to resolve in a later story)], and I think it’s also some of the most interesting kind of video-game storytelling because games whose worlds have a clearly defined metaphysical structure tend to thereby also specify particular relationships between their player, their avatar, and their world. As I’ve emphasized many times before, these relationships are where all the action happens in the special storytelling of video games.” In the second part, “How Dishonored 2 Tried to Undo Dishonored,” I refer to this in the introduction as “my metaphysics-first approach to the analysis of video-game storytelling.” I’m not convinced that this is the best characterization of my approach; others may have done better than I did here by emphasizing the player-centric element to my philosophy of video-game storytelling. To the extent that my characterization is apt, though, I think it’s so because it captures the degree to which my own work is reactive to the general player impulse to grasp at metaphysics, as I describe in the main text. ↑

1 Comment

prfctstrm479 · November 28, 2024 at 12:27 pm

I find the second meditation especially interesting in regards to Xenoblade Chronicles 3. For most of the game, the party is on a race against time to defeat Moebius before Mio’s Homecoming in just under 3 months. There are several scenes in the game that focus on the tension between Mio’s need to finish the quest as soon as possible and the pace at which the party travels through Aionios. However, from the player’s perspective, Mio has all the time in the world. No matter how much time they spend spend playing the game, unless they directly advance the main story to the point where it happens, Mio’s Homecoming will never arrive. Sure, days and nights go by in gameplay, but weeks and months don’t. Hypothetically, the player could spend years just doing side quests, fighting monsters, and/or simply existing, but the avatars would never run out of time. Or, they could put down the game for decades, and not a single second would pass for the avatars. The player really is the doorman keeping the party from the Law.

What I find most interesting about this is how this ludically builds into XC3’s own themes. Just as it does as a fictional world, Aionios exists in an “endless now” as a game world, because without the direct intervention of Ouroboros (fictionally the party, ludically the player), it remains utterly static. This endless now protects its inhabitants from future uncertainty (Mio’s homecoming never gets any closer) but at the cost of developmental/moral/societal stagnancy (the party members cannot finish their growth without continuing the story, colonies cannot be liberated, and Moebius remains the dominate force in the world). The only one with the ability to change things is the player, who can decide to either act as Moebius by playing the game but refusing to advance its main story, or as Ouroboros by making the party progress in their journey, no matter what dangers and unknowns lie down that path.

This works especially well since both Moebius and Ouroboros are in the fiction ultimately concepts, or in my view, attitudes—do you cling to the comfort of the present, or do you boldly face the uncertainty of the future—rather than factions, and everyone is capable of both. Because of that, just by playing the game, the player is required to engage directly in the core conflict of the story on a personal level. That is some very compelling ludic storytelling, (it’s also part of why I’m interested in playing the game and choosing what optional parts of the game to engage with based on what I think the characters would choose to do at the points when they encounter them) and I don’t think I would’ve noticed it without reading this article. Thanks for writing it, and happy Thanksgiving!