A game I initially took to be too childish for me ended up teaching me more about my experience as an adult than any other story in recent history.[1]

(Spoilers are ahead for Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch.)

I picked up and put down Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch more than once over the course of almost a year before finishing it. The reason was one I’ve heard echoed by other gamers: despite the beautiful worlds of the game, the charming characters, and breathtaking soundtrack, the game simply felt “childish,” like a simplistic fairy tale better suited for a nine-year-old closer to the age of the avatar, Oliver, than for a twenty-six-year-old looking for games with “sophisticated stories.”

When I finally finished the game, however, I discovered that those elements that once pushed me away from the game had all along been part of a sly, highly sophisticated storytelling plan to get me to rediscover my own past as a nine-year-old gamer and to critically assess how my relationship with games has changed with my personal development. I want to show you how this game did that to me by creating an unusual and challenging role for its player to fill: namely, Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch makes its player the unwitting soulmate of Cassiopeia, the White Witch.[2]

I begin by laying out exactly how the game’s characterization of its avatar and enemies generate the sense in its player that the game is intended for children. Then, I show how the carefully crafted constellation of characters and interactions at the climax of the game set up a close relationship between the player and Cassiopeia, rendering the player functionally equivalent to Cassiopeia’s soulmate. The consequence is that, just as is the case for the many other soulbonds encountered throughout Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch, healing Cassiopeia consequently heals the player, compelling her to reflect on her own preconceptions of the game and the implications they have on her adult relationship with gaming as a storytelling medium.

Child’s Play: The Misdirection of Audience Expectations in Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch

A childish game implies a childish audience, and Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch’s childishness is exactly what sets up the unique resonance of its story for the adult players who reach the game’s end.

The claim that a game featuring a child protagonist is childish might seem too obvious to explore, but the reality is that there are plenty of child-avatar games from which adults derive plenty of storytelling value. If anything, Link’s status as a child in Majora’s Mask only amplifies the horror an adult player will experience by playing it; Sora’s youth at the beginning of the Kingdom Hearts saga does nothing to prevent the series from tackling squarely adult themes of identity, existence, and relationships, riddled with Disney characters though the games may be; the deeply unsettling universe of EarthBound is intimately related to the relationship between its young heroes and an all-too-adult world.

It’s worthwhile, therefore, to interrogate exactly what makes Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch feel “childish” to the adult gamer in the sense that it seems as though the experience of the game is apt for children and inapt for adults—particularly because the way in which the game establishes this feeling is essential to the story of how it ultimately forces its player to confront her expectations and reevaluate her relationship with gaming. There are two core elements to the game’s childishness:

- Its use of a vocal young avatar

- The status of the game’s enemies as “friends waiting to happen”

Let’s examine each of these in turn.

Oliver as an Unavoidably Childish Avatar

The impact of the first of these elements is clearest when viewed in contrast to a game with a silent child avatar. Time and again, analysts note the utility of Link as an effective “link” between the player and the world of The Legend of Zelda by virtue of his silent character, making him an easy canvas on which the player can impress her own personality; a less obvious consequence of this silence, however, is that an adult player can easily play a Zelda game without feeling like a child.

Though characters like Clock Town’s guards recognize and treat Link as a child (at least until they see his sword), it’s easy for an adult player to conceive of Link as an extension of her adult identity.

When a silent child avatar finds itself in a quest with adult stakes—for instance, the usurpation of Hyrule by Ganondorf, or the annihilation of Termina by a lonely, nihilistic child—the player, directing that avatar’s actions,[3] can easily insert her own adult-oriented reasons motivating those actions. The player directing Link to reunite the star-crossed lovers Anju and Kafei at the cost of sacrificing the world of Termina, for example, can decide to do so based on sophisticated judgments about the transcendent value of love that young Link presumably wouldn’t be in a position to make on his own. Even if it’s not plausible that Link would act for those reasons, it’s perfectly consistent for the adult player to do so; in situations like this, because the avatar doesn’t say anything explicitly ruling out the player’s reasons in favor of more childish reasons motivating the action in question, there’s little friction that comes about from making adult-motivated decisions for a child avatar.[4]

As an avatar, Oliver stands in stark contrast to this model: he vocally expresses his views and motives throughout the story, typically as one would expect a child to do. From classically childish expressions of joy like “Neato!”, to crying when he gets overwhelmed, to expressions of fear about the creatures populating the game’s dungeons, to pure expressions of belief in others, Oliver’s behavior robs the player of any opportunity to gloss over his motivations with their own more mature perspective. The result is that the player remains keenly aware that her avatar is a child with a much different outlook on the world than her own; insofar as the avatar is the player’s direct conduit to the story of a video game, that makes it difficult for the mature player of Ni No Kuni to take it seriously as a game for her rather than a game for a child.

The White Witch’s “right-hand bird,” Apus, succinctly captures the perspective of the adult player: Oliver is the central protagonist of the game, and he is unavoidably characterized as a child.

Again, I’m not identifying this as a shortcoming of the game. Far from it: the preliminary events of the story sew the seeds for this aspect of its storytelling to eventually blossom into a key aspect of the impact this game will have on its adult player. Inside of the first hour of the game, everyone from the hero’s newfound sidekick (Mr. Drippy) to the mysterious, unidentified villain’s feathered henchman (Apus) explicitly points out that Oliver seems too young to undertake the heroic quest set out before him. The player who notices this should be prepared for the game to challenge her assumptions that it’s too childish for her to be playing; yet the trick of the game is that, as time passes and the journey unfolds, the adult player forgets about these early cues and is merely left with the impression that this is an outright childish game—particularly as she travels to another world with Oliver and discovers an arguably more childish element of the game’s storytelling.

“Naive Mechanics”: Conflict as a Prelude to Friendship

Oliver has the opportunity to befriend almost every single one of his combat opponents in one way or another.

Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch offers a tidy explanation of how the creatures that Oliver battles came to be, as well as why those creatures are apt for befriending by Oliver and his companions:

- As Mr. Drippy tells Oliver, creatures come into being from an accumulation of “life force,” which can be positive or negative and respectively begets “friendly familiars” or “wild and vicious beasties”

- Mr. Drippy explicitly characterizes combat with these creatures as a means of “teaching” those brought about by negative life force not to “go round attacking people”

- As Supreme Sage Solomon tells Oliver, Esther, and Mr. Drippy, creatures whom Oliver and his friends impress in combat will “fall in love” with the party

- This creates an opportunity for Esther to use the “heart-winning harp” to convert those creatures into familiars, described by Mr. Drippy as “soldiers of the soul” connected to one’s heart

Consistent with the rest of Ni No Kuni’s world, combat-oriented creatures manifest as a result of human sentiment being either in or out of balance; from this and the nature of familiars, it follows that every creature that initially appears to be an enemy is really just a friend waiting to happen: a being that is apt to bond with the heart of a party member, becoming an ally.

Cerboreas explains that Oliver’s heart saved him from the madness brought on in him by the power of the Star Stone (catalyzed, as we know from the Council of Twelve’s conversations and Horace’s testimony, by Shadar’s influence and the Council’s banishment of him ages earlier).

This nature of “friends waiting to happen” applies equally to the majority of the bosses in the game, who bequeath Oliver with gemstones after Oliver defeats them: after Khulan repairs the wand Mornstar for Oliver and gives him the spell “Unleash,” she explains that these creatures were “guardians, whose poor hearts had been broken by Shadar,” and that “these gems are symbols of the guardians’ gratitude, and contain a part of their spirit and life force” that Oliver can channel by using the new spell in battle. Thus, with very few exceptions, virtually every apparent foe in Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch is implicitly waiting to become the hero’s friend (and most of those that are not, we’ll see, play special roles in the ultimate story of challenging the adult player’s preconceptions about her relationship with gaming).

The existence of an ability for the player to add defeated enemies to her team, most commonly associated with Pokémon, doesn’t entail that the storytelling of the video game in question will be childish. Just consider Persona 5, which features its avatar, Joker, subsuming enemies (Shadows) as a kind of teammate (a Persona) to use in future battles. Despite this relationship with enemies being superficially similar to the one we’ve seen in Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch, I doubt that many would identify Persona 5—a game concerned with confronting the most adult kinds of corruption to be found in the world—as a childish game.

Turning an enemy, a Brutal Cavalryman, into a kind of party member, Berith, in Persona 5.

What makes Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch feel childish, in contrast, is the combination of the two factors we’ve analyzed: Oliver’s constant, vocal expression of his childish perspective hinders the adult player from applying her own more mature reasons and motivations to the actions she directs him to undertake, which makes it similarly difficult for the player to impose any more mature interpretation on combat than the idea that this child, Oliver, is traveling around the world making many friends as a menagerie of creatures bonds to his heart. Over the course of tens of hours exploring the world, this can lead the player to question, or even forget about, the putative stakes of the plot as a quest to save a parallel world from annihilation by an evil force. In the place of that plot, we’re left with a child who’s having a lot of fun with a variety of cute monsters in a fantasy world. While there’s nothing intrinsically faulty about such a plot, it’s the kind of plot whose subject matter might strike an adult as suitable for a child yet insufficiently rich to satisfy the desires of a more mature player.

But this is the kind of clever trap that a story fully explains to you in its first few scenes, knowing full well that the trap will still work because you’ll have forgotten that explanation by the time the game reaches its climax. Within the first thirty minutes of the game, the White Witch—her plot to kill Oliver foiled—(1) underscores that he is only a child, (2) wonders who will be able to guide him on his quest, and (3) muses that the ending of his story will be engaging.

Once the player gets caught in the trap of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch’s ending, she need only look back to those first scenes to see that the game’s message was squarely in front of her all along—foretold by none other than the player’s soulmate.

How the Player of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch Heals Herself by Healing Her Soulmate

On the foundation of a self-consciously childish story, Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch builds a complex analogy of players, avatars, and creators, not unlike the White Witch’s Ivory Tower: by the time the player grasps the analogy’s structure, she looks down to realize the foundation is nothing but clear sky, unveiling the beautiful, pristine world down below.

I want to show you how the game challenges the player to confront her assumptions of what it is for a game to be “childish” and reengage with her own childhood of gaming by telling a story that casts Shadar as a foil to Oliver, the player as a foil to Cassiopeia, and the Zodiarchy and Pea as mirrors for the adult and childhood incentives for playing video games, respectively, with the Wizard King bridging the gap between the two. By the end, we’ll see not only how sophisticated and illuminating the game’s story can be for adult gamers, but also how otherwise confusing elements of its design—for instance, the story’s coda of the confrontation with the White Witch after Shadar’s defeat, the absence of a traditional “New Game Plus” system, and the apparent ability of Cassiopeia to use Ashes of Resurrection without paying the price—are puzzle pieces in a single, cohesive message it is imparting to its audience about the value of optimism over cynicism.

Avatars as Objects and Avatars as Characters: Shadar vs. Oliver

Shadar is more than Oliver’s soulmate: together, he and Oliver constitute a subtle meditation on the nature of avatars—uniquely setting up the player and the White Witch to reflect on their relationships to each other and the world of the game.

Shadar’s title, too easily glossed over as “Executioner,” is a telling, early nod to his function as a foil to the avatar that is Oliver: true to the function of an avatar within the story of a video game, an executor puts into effect the will of another. In the real world (outside the much more interesting realm of video-game analysis), it’s a term most commonly used in reference to the person who carries out the terms of someone’s legal will after they’ve died—directly putting their commands into action. Therefore, while we might be tempted to think of Shadar as the “executioner of the world,” it’s more accurate—and, ultimately, more illuminating—to recognize him as an entity that’s carrying out the will of someone else who is removed from the world and therefore using this entity as the agent of her desires: the White Witch.

Like the avatar of a game, Shadar executes the will of a self-proclaimed “arbiter of the fate of the world” who uses him to arbitrate from afar. Like the avatar of a game, Shadar is solitary in his capacity as Executor: able to marshall assistance as needed, but ultimately solitary in his responsibility for enacting the arbiter’s will (he demands as much in the scene shown above). Like the avatar of a game, he acquires new abilities over the course of the mission with which he is charged (in his case, power to harness storms and to control guardians, just as Oliver is ultimately able to do with “Unleash”). Shadar himself directly tells Oliver, “because I have been granted eternal life, you have been reborn many times over,” though Oliver has no memory of this—an observation I take to be an explicit claim connecting Shadar’s capacity to transcend death with Oliver’s capacity, as an avatar, to restart his quest with no memory of his death each time the player fails in combat.[5]

Functionally, Shadar is deeply similar to a game’s avatar, far beyond the obvious level of sharing a soulbond with Oliver. It’s precisely this symmetry that makes the diametric opposition in the motivation behind their functions so glaring, putting the player in a position to contemplate the dichotomy between the avatar as a disheartened, “adult” object, and a hopeful, “childlike” character, establishing the context for her to subsequently interrogate her own dichotomous relationship to the White Witch.

Shadar’s avatar nature was born from the despair of Lucien, a soldier who was initially an optimist, eager to defend his homeland of Bellicosia and save those who could not defend themselves. The horrors of war—senseless violence against women and children, together with the destruction of his village as punishment for “disobeying direct orders” after saving the girl who would become the Great Sage Alicia—break Lucien’s spirit and lead him to see the world as a place devoid of hope, at which point the White Witch grants him a new identity and purpose as her Executor. This is how Shadar, Dark Djinn and antiparallel to Oliver the avatar, is created.

With this origin story in front of us, the image of Shadar becomes one of the avatar treated as an object: he is a character whose aspirations and identity were beaten into the ground, punished for not following “direct orders” until all that remained in his hollowed-out heart was the directive to obey. This is how he became an apt vessel to be manipulated by the White Witch, who, like disenchanted players of video games, viewed her Executor as a mere tool rather than a robust character with interiority and intrinsic value.

In this context, the quiet redemption of Shadar after his final confrontation with Oliver is made all the more heartbreaking: in a final conversation between Shadar and Alicia transcending time and space, Alicia remarks that Shadar seems to have achieved his goal of “protecting [their] world” by putting an end to war. In the White Witch’s clutches, however, Shadar achieved this sad victory by breaking the hearts of everyone around the world, rendering them as incomplete—and, therefore, as incapable of anything as coordinated and existentially cataclysmic as war—as he personally was.

Analyzing Shadar as the objectified avatar—whose character has been erased by the player in favor of pure, conflict-oriented execution—casts the unavoidable, vocally childish perspective of Oliver in a new light. Oliver is the avatar created as the soulmate of and counterbalance to Shadar. Alicia—the very person whom the once-idealistic Lucien showed pure, selfless kindness—created the perfect vessel to function as that counterbalance: a boy who was spurred on in his own video-game quest by the purest, most thoroughly incorruptible motive imaginable: the love for his mother.

It is this capacity for love, belief, hope, and all the other virtues of heart that identifies Oliver as the “Pure-Hearted One,” and our analysis allows us to more precisely understand why one who is pure of heart in this sense would also be fated to save this world: his purity of heart is what allows him to be an avatar motivated by hope, driving the story of the game to a positive conclusion rather than the inert malaise brought about by his counterpart, ensconced in a thick, symbolically apt miasma until Oliver’s intervention.

Coming to this understanding of Oliver also leads the player to confront a pressing question as she reflects on her earlier preconceptions about the game’s childishness: if Oliver’s explicitly childish perspective is what ultimately empowers him to be such a compelling avatar and hero in contrast to the hollow, desolate avatar of Shadar, what does it say about the adult player that she initially found that childishness to be so off-putting?

It is in answering this question that the player looks in a mirror to another world and confronts the White Witch staring back at her.

How to Save a Player’s Soul: Cassiopeia, Pea, the Zodiarchy, and the Player

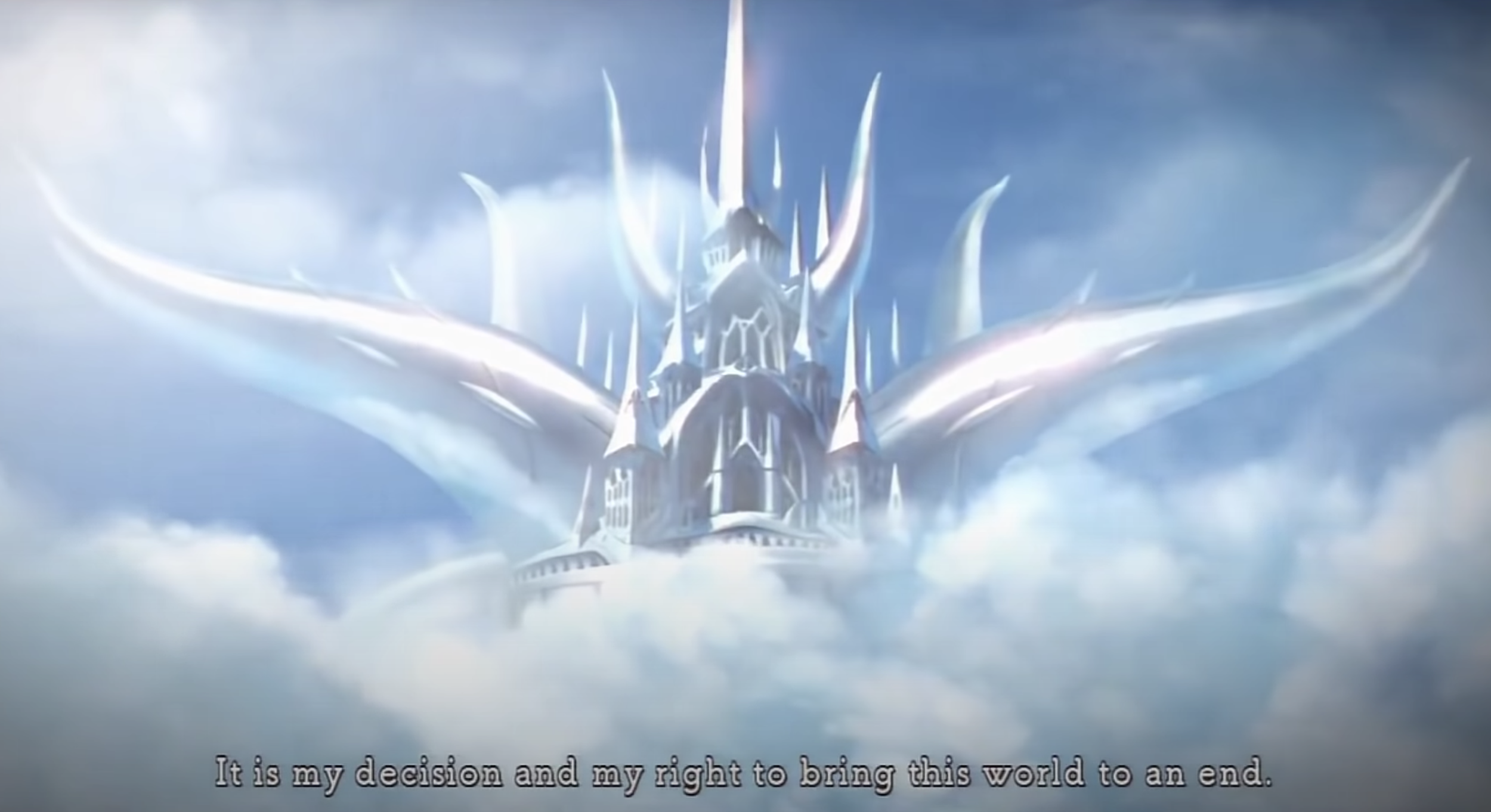

When the player of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch has every reason to expect that the story is over, the world is destroyed before her eyes.

Right in the middle of Oliver waving goodbye to his friends, world, and journey, the disembodied voice of the White Witch introduces the existential threat of manna, the Forbidden Spell.

Despite the presence of foreshadowing regarding the casting of “the Forbidden Spell,” the White Witch’s act of actually casting it after the defeat of Shadar can seem, at first glance, like a total non sequitur: a game that appeared to have just finished a touching and complete story, rounded off with the redemption of Shadar and Oliver fully processing the loss of his mother, suddenly sees a booming voice from above turning all of its beloved supporting characters into violent zombies. Yet once the player steps back and contextualizes manna with her broader understanding of the White Witch, she discovers that this spell is grounded in an impulse that’s much more familiar to her than she might like to believe—and, once she realizes that, a path is opened for her to save herself by saving the White Witch.

Reflect for a moment on what it means for the White Witch to demand an end to the world at the moment of her choosing, particularly when we’ve come to understand her relationship with Shadar as an instrumental player-avatar relationship, devoid of connection to the avatar’s character. The White Witch describes manna as the ability for her and her council to “shape the fate of the world as [they] will,” end it at a time of their choosing, “and start afresh whenever [they] please.” Doesn’t that sound like the action taken by a player who completes the story of a video game, only to wipe out all of the world’s development by resetting the story in a second, “New Game Plus” playthrough—starting afresh whenever she pleases?[6]

The Forbidden Spell, manna, is an application of the White Witch’s perspective on her avatar, Shadar, to the entire world over which she exerts her agency.[7] Manna directly rejects and reverses the dimension of the world that casts even Oliver’s “enemies” as friends-waiting-to-happen: in place of this dimension, it corrupts the nature of every NPC that once had robust, human interests, quests for Oliver to complete, and hearts to be healed: where those characters had relationships and values, manna recasts them as mindless creatures with no function other than being enemies in battle, totally antithetical to the creatures Oliver has come to befriend and literally welcome into his heart.

These “manna monsters,” I contend, aren’t terrifying to the player because of their unsettling visual design or their unexpected position in the conclusion of the plot: they’re terrifying because they indicate that the White Witch’s perspective is a natural consequence of the “mature player” who has distanced herself so far from her childhood perspective on games that she treats games, implicitly or explicitly, as mere processes to complete again and again, demanding unambiguous enemies, a clear-cut conclusion to an easily replayable plot, and entertaining objects to use as instruments of her entertainment along the way. Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch thus turns an apparent non sequitur into a hauntingly logical climax, setting up the player to ask and answer two final questions that lead to a uniquely restorative and cathartic conclusion:

- How did the White Witch—and, by extension, the player—arrive at this corrupted, cynical perspective in the first place?

- Can the White Witch—and, by extension, the player—return to the purity of a more childlike appreciation for this world and its inhabitants?

Cassiopeia’s Path to Corruption

The answer to the first part of the first question is that Cassiopeia, Queen of Nazcaä, was thrust into a role of agency and authority too quickly. In the final stages of the game, we learn that that Cassiopeia’s father, the Wizard King, was a peerless war hero who united a fraught civilization and came to be crowned a wise ruler who “treated all his subjects equally, be they humans, animals, or magical creatures”; under his leadership, “[a] new era of peace was dawning” in the ancient kingdom of Nazcaä.[8] In the face of this beneficent omnipotence, the majority of the Council of Twelve—the consortium of wizards at the head of day-to-day governmental operations in Nazcaä—feared that their own power would be eclipsed; to avoid this, they clandestinely assassinated the Wizard King.

This led Cassiopeia to become a classically naive childhood ruler, wishing the best for her subjects while the Council of Twelve quietly orchestrated all the real governmental decisions, driving Nazcaä to ruin while making Cassiopeia the public entity for citizens to view as responsible for those decisions. The Council banished all of the Wizard King’s most trusted supporters, robbing Cassiopeia of anyone who would give her proper guidance on how to become a benevolent capable ruler like her father—not to mention how to use the kind of powerful magic that only such a ruler could responsibly manipulate.[9] It’s telling, in this regard, that Cassiopeia’s only apparent friend, Apus, is a parrot, a creature who only echoes what he’s taught to say: Cassiopeia found herself in a position of authority with no one to show her how to responsibly use it as a wise adult, such as her father, would.

Cassiopeia’s well-intentioned desires to improve the lives of her subjects, ground into the dirt by the will of the Council, lead her to cast the Forbidden Spell, which she expects to restore the well-being of her citizens—only to see them transform into monsters of the kind Oliver encounters after the White Witch casts manna following Shadar’s defeat. The manna persisted until “there was no one left” except for Cassiopeia, leaving her “completely and utterly alone.” Cassiopeia became crippled by her loneliness and guilt such that, when her younger self came in the form of Pea to confront her, she banished this representation of her past self—and it was this banishment that fully aligned her perspective with that of the Council, causing her to manifest illusions of them as her advisers and transforming her into the White Witch.

It is at this moment, upon her transformation into the White Witch, that Cassiopeia reinterprets her use of manna, changing her view of the spell from something gone horribly wrong to something that is her divine right: the ability to “start [the world] afresh whenever [she pleases],” after shaping it according to her will. This journey of Cassiopeia’s—from a well-intentioned but naive child to a corrupted cynic who understands the capacity to restart the world as something to which she is entitled—forms the groundwork for understanding Cassiopeia as someone who shares a soul with the adult player of Ni No Kuni, paving the way for the player to save herself by saving Cassiopeia.

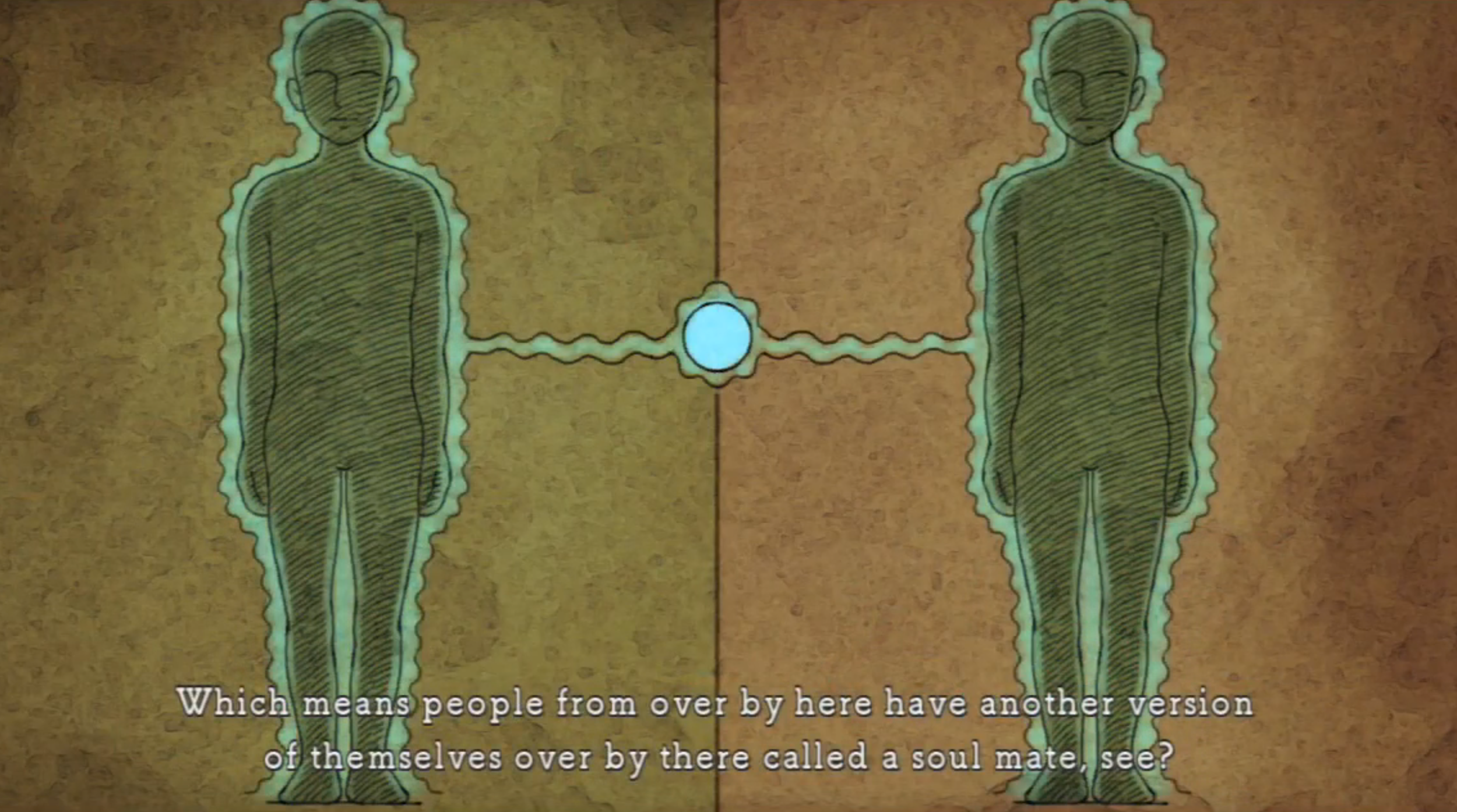

The Player as Cassiopeia’s Soulmate

To quote Mr. Drippy, “If two people are soul mates, there’ll be similarities somewhere. You’ve just got to keep an open mind and a peeled eye!” With an open mind and peeled eye, then, let’s retrace Cassiopeia’s journey and see whether we can find the image of the player of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch in her fall from grace.

Like Cassiopeia, the player who first encountered video games as a child initially found herself in a magical world with wonderful creatures and compelling individuals. Perhaps, like Cassiopeia, the player had a more adept guide who helped her to first explore the world of video games before she started playing them herself—a parent, an older sibling, or some other “Wizard King,” whose mode of engagement with these interactive worlds she idealized.

Yet, like Cassiopeia, when this player was young, a point came when she had to pick up that controller on her own for the first time and play a game without the watchful guidance of her “Wizard King,” thrust into the role of authority and agency too quickly. In the absence of this role model to emulate, the player is left to the guidance, rules, and counsel intrinsic to whatever game she’s playing: she is a naive, good-intentioned agent being directed by systems that are oftentimes, in one way or another, more cynical than she is at that moment in her development.

It may seem at this juncture that I’m making the supposed experience and history of an adult player of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch too specific to be broadly applicable and relatable, and perhaps I am—but I’d encourage you to consider whether this part of the story I’m telling you is really that unusual. While there’s no hard-and-fast rule of video-game storytelling in this regard, it strikes me that those video-games with more sophisticated stories and interesting worlds generally tend to be more oriented toward violence, treachery, and the other more “adult” themes that make a game’s story more engaging at the cost of contravening childlike innocence.[10] With this in mind, as a child gamer begins gaming on her own and seeking “games worth playing,” it’s likely that she’ll be exposed to these more adult themes—not to mention to subtly sinister game mechanics such as “New Game Plus” systems.[11]

Like manna, New Game Plus—a system by which the player of a game is given the ability, and is encouraged, to restart the game’s story with the same avatar upon completing it—is an unexpectedly central and telling symbol in this story of the path to cynicism. The childhood, naive response to a story beset with violence and conflict for all of its characters is to try to find a way to save them all, yet the naive child who proceeds through one of these more “mature” stories with this goal will ultimately find a system that concludes not with a final “and they lived happily ever after,” but rather with a directive for her to start the world afresh, effectively erasing whatever humanity the player might have seen in those characters in favor of treating them as mere game objects to be annihilated and reset as the player sees fit.

If you, like me, are a gamer who has become so “literate” in games as to treat New Game Plus mechanics as a mere stylistic norm, then step out of the analysis for a moment, think back to the ash falling on Ding Dong Dell, and consider how barbaric it is to invest tens or hundreds of hours in saving a people and their world only to wipe that out and set everyone back to zero as soon as their story has reached its happy end.

It’s no wonder, then, that a player who was subconsciously taught to treat these systems within games as the norms and absolutes of “serious” video-game storytelling would recoil at any sign that invites her to reconsider that child who first fell in love with the characters and worlds of games in the first place. Like Cassiopeia, who banishes Pea and transforms into the White Witch, the player turns away from games with avatars like Oliver and “enemies” like Familiars as “too childish to warrant taking seriously”—and, in so doing, she becomes a cynical player who treats even those games she loves as mere systems for her to manipulate, rather than worlds and characters to honor and enjoy without pretense.

By exercising her agency over that system and its conflict-based story over and over again, the player condemns its characters to suffer… forever.

The player of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch looks at Cassiopeia and sees “another version of herself.” Another game could stop here and simply leave the player horrified at the parallels between herself and this tragic antagonist. However, Ni No Kuni is not a horror game: it reveals these aspects of its player only to give her an opportunity to heal herself along with the White Witch, unlocking a kind of pure-hearted optimism she may not recognize save for, like Cassiopeia, within her most distant, fading memories.

We’ve arrived at the second of our two questions: Just how can Cassiopeia and the player bridge the gap from their corruption to their salvation?

How the Intercession of the Wizard King, Pea, and Oliver Heals Cassiopeia and the Player—and Topples the Zodiarchy

The great conspiracy of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch is a plot between three characters to heal both Cassiopeia and her soulmate, the player.

Breaking through the “barrier” (to use the Wizard King’s word) of the White Witch and the player’s cynicism is no small task, especially given the agency they are both able to exert over the game’s world. Accomplishing this task requires the carefully orchestrated coordination of a triad of characters, each of which plays a key, distinct role:

- The Wizard King’s ghost, masquerading as Gallus, is, true to his title, “The Power Beyond the Throne”: he understands what it looks like to govern omnipotently from a place of wisdom and beneficence; he understands how his daughter, Cassiopeia, erred and became corrupted in the first place; and he understands how to coordinate Pea and Oliver in a bid to save Cassiopeia—and, by extension, Cassiopeia’s soulmate, the player.

- Pea, a manifestation of Cassiopeia’s younger, innocent self, serves dual functions: she is quite literally Cassiopeia’s missing “inner child,” who must confront her and reintegrate with her in order to sanctify Cassiopeia’s soul, and she is repeatedly the agent who empowers Oliver to have mobility and agency as a protagonist and avatar, encouraging him—with her own older self’s errors in full view—to be the kind of hero who can truly save the world, showing a better outlook for the world that can heal both Cassiopeia and the player.

- Oliver, the Pure-Hearted One, is the avatar so pure that the player initially balks at his childishness; emboldened by Pea and guided by the Wizard King’s distant plotting, he gains the courage to show a better path than Shadar’s to an avatar saving the world: one that truly saves everyone and restores in Cassiopeia and the player their childlike bond with the world and its characters.[12]

Pea gives Oliver his first wand, a branch of the Nazcaän Sky Tree, empowering him to traverse worlds and begin his pilgrimage; Pea helps Oliver to understand and navigate the world of soulmates in Motorville in order to heal both his world and Cassiopeia’s; Pea shows Oliver the countless brokenhearted people he’s healed—across both worlds—when he withdraws inwards following the revelation that his mother is dead and he cannot save her. When the manna falls, Pea purifies the actions of her older, cynical self in the way that only a child can: by casting a spell she calls “Sanckify.”

In the background, the Wizard King quietly guides Oliver to gain the proper tools of wizardry as he becomes ready for them, cultivating him into a capable and thoughtful wizard whose only peer is the Wizard King himself. By gradually gifting Oliver with both of his own wands as Oliver gradually explores the world and uncovers his own strength of heart, the Wizard King gives Oliver the requisite power to accompany the wisdom and perspective on the world with which Pea and his friends have imparted him.

The result of this conspiracy is that Oliver, a character whose purity the mature player initially cannot take seriously, becomes, by the end of the story, a hero capable of reminding both Cassiopeia and the player the very adult virtues of a childlike connection to the characters and worlds of stories.

When a fully actualized Oliver finally reaches the chambers of the White Witch with his friends, the White Witch’s challenge to him is simple: she wants to know what the world is, that it would warrant preservation rather than annihilation. Her complaint against the world is even simpler, albeit deeply provocative: she objects that the world is “imperfect like the human heart.” This is a provocative claim because it contains, in one simple statement, both (1) the adult player’s original resistance to the intrinsic value of video-game worlds and (2) the answer that Oliver, Pea, and the Wizard King have subtly given her to that resistance over the course of their entire journey together.

It’s natural that the player who’s been conditioned to treat games cynically as mere systems would view games’ worlds as imperfect: when conceived as a mere system waiting for the input of a player, these worlds simply are imperfect in the sense that its characters cannot be fulfilled and its conflicts cannot be resolved without the agency of some entity that exists beyond the world itself (i.e. the player). For the player who takes this stance toward the worlds of games, the entitlement of the White Witch is a natural sentiment at which to arrive: “After all,” the player might say, “if any perfection in the world is entirely contingent on my input, then why shouldn’t I be able to wipe the world’s slate clean and start it over whenever I wish?”

At the same time that the player empathizes with the White Witch’s complaint, her phrasing calls to mind all the stories the player has enacted over the course of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch that show why the White Witch is ultimately misguided. Time and again, Oliver and the player have encountered brokenhearted characters—those with hearts that are imperfect by virtue of lacking a key attribute—only to use Oliver’s wizardry of “Take Heart” and “Give Heart” to restore the balance and happiness within them.

The nature of this healing mechanism flies in the face of the White Witch’s—and, by extension, the cynical adult player’s—expectation of the world’s imperfection. The White Witch’s own actions reinforce her views of the world being something that cannot be completed without the intercession of an outside force: remember, it is the White Witch’s avatar, Shadar, who is responsible for breaking characters’ hearts in the first place. In this way, the actions of the White Witch’s avatar are actually a kind of logical fallacy, rendering the world imperfect and subsequently claiming that she is entitled to shape the world as she wishes because it is imperfect.[13] In stark contrast to the White Witch and Shadar, the healing actions of Oliver and the player show that the world of the game intrinsically possesses everything it needs to restore its characters and make everyone happy. The mending of broken hearts doesn’t come from tapping into some kind of unknowable wellspring of virtues that exists beyond the game’s world: rather, it is a rebalancing of the world, borrowing from those characters with excess of a virtue in order to help those with a dearth of that virtue. This shows the player that the White Witch is being myopic: she thinks the world is imperfect because she is focusing on individual shortcomings rather than seeing the holistic picture of a world in which characters can empower each other to be happy and lead fulfilling lives.

This understanding of the capacity of characters to heal each other empowers the player to ultimately sympathize with the ruthless optimism of an avatar who once struck her cynical, adult self as “too childish” to warrant taking seriously; it empowers her to find a world in which apparent “enemies” can be restored and befriended as aspects of the avatar’s heart refreshing and mature. The player coming to this understanding thus forms the final step in the Wizard King, Pea, and Oliver’s conspiracy: the player is able to overcome the brokenheartedness of her own adult cynicism, putting her in a position to thereby heal her soulmate, Cassiopea.

I don’t take it to be a coincidence that Cassiopeia’s transformation into the “Monster of Manna” is preceded by, to use Mr. Drippy’s words, “black misty stuff” (shown above): stuff of the exact same variety he claims are characteristic of a Nightmare, “an evil spirit that latches onto the brokenhearted.” In my view, this indicates that the Monster of Manna really is, just like the other Nightmares in the game, the final bastion of spiritual corruption that the party must invade in order to purify the afflicted character and her soulmate. The boss’s name is all the more telling in this regard since, as we discussed above, Cassiopeia and the player’s misinterpretation of manna as their right to restart the world forms the core of their corrupted perspective about the value of this world and its characters.

Recognizing the error in her own previous perspective, together with the final defeat of Cassiopeia’s Nightmare, puts the player in a position to heal both herself and her soulmate, Cassiopeia, merging a brokenhearted Cassiopeia with Pea and recalling the player to her own purer, younger perspective of the intrinsic value of simply enjoying the world and characters of a game for the rich entities that they are. This, by Cassiopeia’s own account, is how she is “restored to her true self”—not her child self, but rather the authentic and holistic identity she had shunned in favor of a cynical mask. Her relationship to the player is underscored in a final flourish when she later expresses to Oliver and his friends that, rather than restarting the world, she wants to use flowers to “make everyone happy” and allow the world to bloom, embracing an ending in which she cherishes the world for what it is rather than starting it over as a mere system designed for the exercise of her will.

But recall, before we reach “Happily Ever After,” that Cassiopeia and the player’s hearts did not break on their own: they were made cynical by the external systems of cynical, manipulative Councils and game systems they were too young and innocent to understand. It’s only logical, then, that Cassiopeia and the player would not be able to truly assert their restored perspective on the world until they thoroughly denied those systems that broke their hearts in the first place—a trial represented by the final enemy in the story, the Zodiarchy.

As an amalgam of the Council that led Cassiopeia down the path of corruption and the systemic design that led a younger player to cynicism about game worlds, the Zodiarchy makes a chilling promise: now an independent entity that determines the fate of the world, it shall bring the world to the end, and “a new White Witch shall reign supreme.”

That promise is precisely, to use Marcassin’s words, a “declaration of independence”: it’s a declaration that neither Cassiopeia nor Ni No Kuni’s player is the White Witch per se: rather, “the White Witch” is a role that can be occupied by any sufficiently powerful, metaphysically influential agent made cynical in the way that Cassiopeia and the player were made cynical. To truly “save the world,” then, the player and Cassiopeia must not only heal themselves but also destroy the system that broke their hearts in the first place. They must, in the final confrontation of the game, reject that existential, almost inevitable impulse to start the game all over again.

This, in my view, is the meaning of the final confrontation with the Zodiarchy, and it’s their defeat that makes it metaphysically possible for the world of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch to persist, happy and complete, rather than being endlessly reset by pernicious systems and players. This is the reason that, rather than following the final battle with an invitation to “start your adventure over from the beginning with the same characters,” the reward for completing the primary storyline of Ni No Kuni is the simple directive to “enjoy everything this world has to offer,” with more quests, more people to make happy, and no reset button.

But this healing of Cassiopeia and the player’s perspective is not without sacrifice, and that sacrifice shows why the player, like Cassiopeia, doesn’t merely revert to her childhood self once she’s healed: rather, she comes to appreciate the childhood love of a game and its characters from a more adult vantage point. Again, Cassiopeia’s story shows us what this sacrifice means not only for her, but also for the player—and understanding this final chapter in her story requires us to revisit the nature of manna, “the Forbidden Spell.”

The rune representing “Ashes of Resurrection,” the Forbidden Spell—crossed out to indicate that it is off-limits.

After the final face-off with the Zodiarchy and the conclusion of the game’s primary storyline, the Forbidden Spell, “Ashes of Resurrection,” is added to the Wizard’s Companion, clarifying that this is the spell that the White Witch misunderstood as “manna”: it is described as a spell “capable of bringing the dead back to life,” albeit at “a terrible price to the caster.” This explains how a young Cassiopeia—left without her magic teacher (Horace) to explain to her the dangers and proper uses of such a spell—could misinterpret the spell and be corrupted into viewing her capacity to “bring the dead back to life” through annihilating and restarting the world, just like the player, as some kind of divine right. However, this poses another pressing puzzle: after Cassiopeia has been healed, she joins Oliver and his friends in battle against the Zodiarchy, and she is able to “properly” use “Ashes of Resurrection” to revive party members in the event of the Zodiarchy killing them. Since Cassiopeia appears to be fine after the battle and no one in the party turns into a “manna monster,” this raises the question: exactly what price does Cassiopeia pay for using “Ashes of Resurrection” to empower Oliver’s party to defeat the Zodiarchy’s expectations for the future of the world?

The price she pays, in my view, is one of self-erasure: her mature use of “Ashes of Resurrection” empowers the world of the game to be preserved and its people to be made happy, but Cassiopeia herself is not able to participate in that world. When Oliver is left to enjoy everything the world has to offer after the Zodiarchy is defeated, Cassiopeia reverts to her state prior to the final battle: she still awaits Oliver and his friends in the Ivory Tower in the form of the White Witch. I see this as an especially compelling way to understand the price a player-like agent would have to pay for committing herself to the preservation of a game’s world: to preserve that world is to recognize the value of its characters and allow them to live their lives without interference from that agent, meaning the agent cannot participate in that final, happy outcome of the world.

This opens the way for us to see the sacrifice of the player in the same way: it’s true that, unlike Cassiopeia, the player is able to participate in Oliver’s further adventures once the game’s world further opens up after the defeat of the Zodiarchy, but there still comes a time when the new quests are completed, everyone in the world is happy, and there’s simply nothing left for the player to do there that would further advance the world. In a game with New Game Plus mechanics, as the Zodiarchy advocates, the basic architecture of the universe is built such that the player always has something to do and can always stay attached to the game’s world by virtue of wiping the story clean at the end and restarting from the beginning; in contrast, in a world such as Ni No Kuni’s, the player is compelled by virtue of recognizing the inherent value in the world’s characters to step back, put the game down, and truly walk away once there’s no one left to help or otherwise make happy. There is a point at which the player, having done everything she can to honor the world’s characters, must erase herself from that world, severing her direct connection to it much as Shadar severs his soulbond with Oliver.

To do that requires a nuanced combination of characteristics that Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch uniquely cultivates in its adult player: it requires the maturity of letting go, motivated by a childlike capacity to genuinely honor the lives of the characters in a work of fiction, with no ulterior motives. It’s this nuanced character that gives Ni No Kuni a deceptively sophisticated and adult story that accomplishes something perhaps only possible through a collaboration between Studio Ghibli and the medium of video games: it causes you to look back on your own “Pea,” your own childhood gamer, and rediscover that perspective on games without lapsing fully backwards into it.

“Oliver… I have to go now.”

It’s Christmas Day, 2003. You are nine years old.

For the past few months—it seems like years—you’ve been sneaking glances in Toys “R” Us at the elusive, sequestered corner of the store where the “video games” live. On the screen facing out of that corner, you’ve seen the same miracle take place every time: a plumber flies through the air, jet-propelled by a water-pump backpack, going on all sorts of adventures. But the miracle isn’t the plumber himself: it’s this portal to other worlds, a magic box that turns the TV you only use for TV shows into an entire new universe where you—yes, you!—can be someone else, meet new people, and do the truly fantastical.

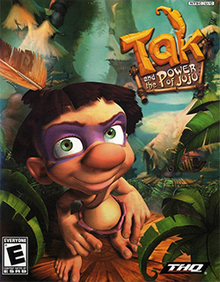

Christmas Day, 2003, and you unwrap one of these magic boxes at the crack of dawn under your Christmas tree. Just shortly after that, you unwrap an entire world that was waiting nearby, just next to the box under the tree: Tak and the Power of Juju.

You don’t yet know that the unexpected games bundled together on the box’s promotional disk, which you’d never even heard of before, will eventually change your life and shape your perspective on how stories can and should be told; right now, you don’t think enough about storytelling to understand the final impact of Santa giving you that magic box.

What you do know is that you are about to disappear into that box for days, weeks, months on end, living in the world the box spins into existence what you put in that tiny Tak and the Power of Juju disk. Tak isn’t a means to a story: he’s an extension of yourself, the means by which you get to live in this world—battling Tlaloc, befriending Flora, saving Lok (you have no idea who Patrick Warburton is yet)—and fall further in love every day with this world that is fantastical, charming, and something that this magic box allows you to experience as yours.

In the years to come, you’ll discover that there are more magic boxes, more worlds they can call into existence, and the more closely you look at those worlds, the more you’ll uncover how remarkable their stories are, teaching you lessons that you’ll never get from novels, movies, or plays. You’ll fall in love with the storytelling, and instead of spending time with characters like Lok, you’ll start talking about characters as “complex semantic units” as you try ever harder to understand just what it is about this magical thing called ‘video-game storytelling’ that lets it accomplish narrative feats inaccessible to other media.[14]

Then, one day, you’ll find a game called Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch, and, seventeen years after today, you’ll be right back here, on Christmas Day, 2003, remembering Tak not as a story but as a collection of friends you were proud to have in a world you were champing at the bit to live in. It will be at that moment that you can be thankful for video games not just as an unparalleled mode of storytelling, but also as a staggeringly sophisticated experience machine that lets you simultaneously appreciate stories and form authentic, unique relationships with those stories’ worlds and characters.

Before Ni No Kuni, you’ll be convinced that you have to choose one or the other of these perspectives on video games. From Ni No Kuni onward, you may hold both of them in your mind and heart as a player at every moment you spend gaming.

- Thanks to Dan Hughes for comments on earlier versions of the ideas represented in this article. ↑

- I should add three qualifications at this point. First, I’m not claiming that this interpretation of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch renders it a game that’s only appropriate for adults: the fairytale and childlike elements of it, which serve a particular function in this analysis, also make it a perfectly charming and moving game for younger gamers. Second, I’m not claiming that this analysis of the story is what the creators of the game literally intended to express through the story: my claim is that there are enough data within the game itself to support reading it in the way I propose in this article, whether or not the creators intended that to be the case, and not necessarily to the exclusion of other interpretations. My hope is that, at a minimum, other gamers who fit my own persona of having played this game at an adult stage in their life after growing up with video-game stories will feel the pull of this perspective on the game. Third, in the spirit of the first two points, when I refer to the ‘player’ of the game in this analysis, I’m assuming an adult player who grew up playing video games from a young age. ↑

- I use the vague language of “directing that avatar’s actions” because you can run a version of this argument regardless of the particular theory you have of how the player of a video game relates to the avatar of the game within the fiction of that game, though the details of the argument will vary based on your favored theory (cf. Note 4, below). My own preferred theory of the fictional player, which I introduce and defend in my “The Role of the Player in Video-Game Fictions,” offers a clean explanation as to how the player can make it the case that the avatar does things for reasons unavailable to the avatar: simply put, the player’s actions within the fiction are of a separate, more metaphysically foundational kind than those of the avatar. ↑

- Little friction, but there is a modicum of friction that points to a broader theoretical issue that’s beyond the scope of this article: when the player is directing the actions of an avatar based on reasons that the avatar itself couldn’t possibly be acting on, we probably need some way of inferring the reasons on the basis of which the avatar itself chose to act. Where you come out on this issue depends on the broader epistemic relationship in which you believe the avatar of a game stands to the player of the game (cf. Note 3). ↑

- Some have taken this claim of Shadar’s and instead inferred that Shadar gained eternal life by defeating many previous incarnations of Oliver in the past (for instance, the entry on Shadar on Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch’s Fandom Wiki, as of the time of this article’s publication). Unless I’m missing further evidence in favor of this conclusion, this strikes me as a pure misinterpretation of what Shadar is saying. In the first place, it gets the causal relationship between Shadar and Oliver backwards: Shadar says that Oliver has been reborn many times because Shadar “gained eternal life,” not that Shadar gained eternal life because he defeated many previous incarnations of Oliver. In the second place, I see no other evidence in the game for the view that there were many previous versions of Oliver that Shadar somehow defeated: the closest we come to this is Shadar’s declaration, in the memory of his confrontation with Alicia, that he “[severed] all ties with he who shared [his] soul,” after which Alicia declares that “souls are reborn after a time” and travels to Oliver’s world in the future, implicitly giving birth to Oliver thereafter. In the absence of further context, it seems that whatever Shadar did to sever ties with his previous soulmate was a one-time occurrence since he portrays the act to Alicia as something he expected to be permanent; since we know that “Breach Time,” which Alicia uses to reach Oliver’s world, can only be used once in a lifetime, it doesn’t seem plausible that there was somehow a plurality of Alicias who begot many incarnations of Oliver. The conjunction of these factors and what I take to be ample support I’ve shown for the functional, avatar-based symmetry between Oliver and Shadar leads me to view my own proposed interpretation of Shadar as the most coherent way on-net of understanding his admittedly cryptic claim. ↑

- Those familiar with my work on metaphysical vampirism in Code Vein will mark the structural similarities between the relationships in which the player stands to the main antagonist of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch and the main antagonist of Code Vein. It’s especially interesting in this regard to note that the horror of Code Vein, in my view, comes in part from the inability of the player to escape or act outside of this cycle of completing the story only to repeat it; in contrast, as we’ll see (similarly to the scenario I discussed in some of my commentary on that Code Vein article), Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch offers a path of healing and optimism for the player in part by preventing them from restarting the story upon its conclusion. ↑

- The savvy reader might point out that the game ultimately reveals to us that “the Forbidden Spell” is actually “Ashes of Resurrection,” rather than this perverse version of it that the White Witch uses following Shadar’s defeat. At this moment in the analysis, I’m interpreting the meaning of the spell as it is understood by the White Witch, as it is her perverse understanding of the spell that illuminates her as a mirror of the adult player’s own perverse tendencies. Shortly, we’ll see that this analysis also illuminates the meaning of the spell as a beneficent mode of resurrection and explains why a spiritually restored Cassiopeia is seemingly able to cast the spell during the Zodiarchy battle without adverse consequences—one of the most seemingly intractable puzzles of the game’s finale. ↑

- The ghost of Horace—the Wizard King’s brother-in-arms, a member of the original Council of Twelve, and Cassiopeia’s tutor—is the source of this history of the rise and fall of the kingdom of Nazcaä. Along with the illusions of the queen’s honor guard and the flowers containing Cassiopeia’s memories, Horace is one of the primary windows available into Cassiopeia’s origins. ↑

- Horace’s ghost eventually admits to Oliver, ashamed, that he was responsible for Cassiopeia’s magical education and fled Nazcaä before its completion, sensing the danger he was in and prioritizing his desire for revenge on the Council over his obligations to Cassiopeia. ↑

- The reader might point out that there is an increasingly popular strain of video games that challenge the assumption that video games require violence in order to be engaging and sophisticated in their storytelling and gameplay, but that’s exactly my point: this analysis of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch counts the game as a part of this strain, and as an early and especially advanced entry in that strain, at that. Undertale, which many laud as the benchmark in compelling, anti-cynical video-game storytelling, was published in 2015; Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch was first published in 2011. ↑

- I hope at this point that this goes without saying, but, at the risk of being misinterpreted, nothing I say ought to be construed as to support the baseless claim that video games somehow cause their players to become violent. My analysis here is merely making observations about the way in which child gamers are led to treat the worlds and characters of those games as disposable entertainment systems and are thereby distanced from their original enchantment with those worlds and characters. Nothing here makes the leap from what people do inside of fictional worlds to what they do in the real world—a leap that, not coincidentally, is where I think many of the “video games cause violence” arguments make their key mistake. ↑

- “Gaining courage” here is a manner of speaking because the Pure-Hearted One, by definition, bears all the virtues of heart attributed to the Locket in the world of the game and one of those virtues is courage. Strictly speaking, it’s probably more accurate to say that Pea either reminds him of his courage or imparts him with the maturity to recognize his courage. ↑

- More specifically, this is a rather metaphorical instance of begging the question: through the actions of Shadar, the White Witch is assuming the truth of the very thing she is trying to prove (by rendering the world imperfect and thereafter deeming it to have been imperfect even before Shadar’s actions) ↑

- No disrespect meant at all to Mieke Bal, from whose work I learned and often borrow this definition (see Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative (1985), p. 113.) ↑

2 Comments

Caymus · February 6, 2021 at 11:49 pm

Interesting. Definitely a good partner to the Code Vein article, though I find this interpretation more believable than that one. Just goes to show you that entertainment aimed at children isn’t inherently childish, immature, or unsophisticated (Looking at you, Avatar: The Last Airbender!).

The more I consider this idea of the player unintentionally perpetuating the game world to the detriment of the characters they grow to love over the course of the game, the more I notice similar concepts tackled in other games. One that immediately jumped out to me was Dark Souls. Despite telling a story about the consequences of perpetuating cycles, Dark Souls has fostered a fanbase that loves NG+ runs, and the game itself somewhat promotes this behavior with the potential for a NG+7. Thinking about it further, it seems like Dark Souls wants the player to replay it at least once since it’s two endings represent two drastically different thematic outcomes: the “Link the Fire” ending perpetuates the world in the same way Gwyn did while the “Age of Darkness” ending breaks the cycle and accepts the uncertainty of the future. It’s almost like Dark Souls wants the player to play once, get the “Link the Fire” ending, and play a second time to get the “Age of Darkness” ending. This interpretation makes some sense seeing as the “Link the Fire” ending is available to all who beat the game, but the “Age of Darkness” ending requires some effort to unlock, with the latter ending being the more thematically resonant one. Through this structure, Dark Souls seems to decry the perpetuation of game worlds through systems like NG+. I could see this making an interesting article in the future!

As a final point, I want to ask you, Aaron, to elaborate on your personal thoughts on NG+ systems, considering you’ve written two articles about games that arguably criticize them. Do you see any solutions to combat this issue of malicious perpetuation of game worlds?

Thanks for the engaging read. Looking forward to what you’ve got coming next!

Aaron Suduiko · February 7, 2021 at 6:17 pm

Caymus! Thank you for reading; I’m delighted to hear you enjoyed my work. And, yes: cheers to “childish literature” that oftentimes teaches us more than “mature” artworks.

I’m also thrilled that these explorations of mine in Code Vein and Ni No Kuni are getting you to notice similar themes elsewhere. As a biographical aside, that’s a big part of what inspired me to grow With a Terrible Fate into what it is today: after getting deep into my theory of Majora’s Mask, I picked up Xenoblade Chronicles for a replay and discovered that my research had given me a new way to read its ending. Analyzing video games can truly be a virtuous cycle in this regard.

…and, speaking of cycles: what a great context in which to consider Dark Souls! I absolutely love the idea you’re playing with of there being a “narratively correct” sequence in which to play games with multiple endings; we should talk about that further. For my own part, one of the many, many things I love about Dark Souls is that the inescapably cyclical nature of its storytelling makes it uniquely poised to force the player to confront the classic absurdist challenge of making meaning in a world that refuses to offer you any meaning or even a conclusion to your journey. In my own view, it’s instructive to view Dark Souls’ storytelling not just as a single game but rather as the overall series: when we do so, I think we uncover a surprisingly heartwarming journey in which the player who is initially forced to confront a world that refuses to make her actions meaningful ultimately gains the power to enact that very same universe through the sheer force of asserting her will (I spell out how I take these awesome dynamics to come about in my article on Dark Souls’ special brand of “closed storytelling”).

Dark Souls is a good bridge to your last point, too, Caymus, because it’s an example of a video-game story that I think has special meaning by virtue of its peculiar cyclical mechanics. So, I don’t think NG+ systems are intrinsically “bad” or anything like that (although, to the extent that a given game’s universe casts that kind of resetting as bad, narrative devices like Ni No Kuni’s anti-NG+ or Nier‘s data deletion are compelling alternatives): my broader point at the moment is simply that these systems, which many gamers and analysts still consider to be beyond the scope of what we ought to call a game’s “story,” often have stark and informative ramifications for how we ought to consider a game’s story and our role in it. As I teased at the end of my Code Vein article, I believe that many of the most interesting meditations on the ethical universes of video games are happening nowadays on this level of the moral valence of the player’s metaphysical relationship with a game’s world. I have a few more bugs in my brain about games that offer really interesting and provocative meditations on this topic, so stay tuned!