The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask is a game nearly as old as I am. It’s one that I indulged in well before I could read, let alone have any comprehension of the game’s tones or themes. I have replayed the game again and again throughout my life, losing count of the number long ago. Often, I used it as an emotional palate cleanser through moves, graduations, and heartbreak.

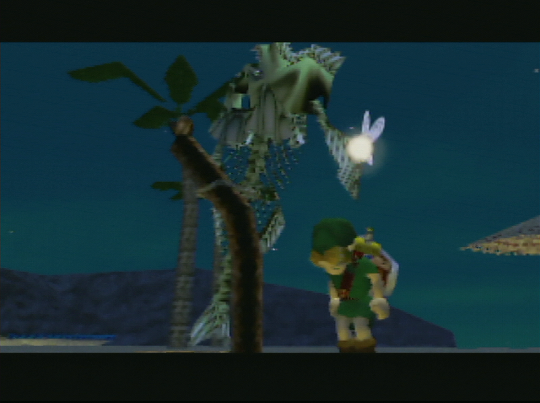

And yet, playing through this game for the umpteenth time, I noticed something that had never registered before. There, in the spotlight shining down on Skull Kid as he floats menacingly above a newly transformed Deku Link, lay a single detail I had never clued in on.

A broken Triforce.

A newly transformed Deku Link, watching Skull Kid hover above a broken Triforce.

The image sent me down a spiral of questions, rejuvenating my love for games, life, and narrative design in one frame. Link has now fallen so far down the proverbial rabbit hole that he is in another realm. He is stuck in a weak and helpless form, with his sword, horse, and ocarina stripped from him; powerless, alone, and not himself.

This is a detail in Majora’s Mask that many have noticed and looked to contextualize, but perhaps let go as a minor detail as it is never repeated. Some refer to the image as an inverted Triforce, theorizing it represents the strangeness of Termina.[1]

However, the image itself isn’t inverted relative to Link’s visual field. From Link’s perspective, this is the Triforce, with one piece of it smaller and fallen below the rest. From Link’s perspective, it represents how far he feels he has fallen.

And in parallel with the image in the spotlight, Link himself, the wielder of the Triforce of Courage, has fallen. He is disconnected from his context, his past, and his perception of himself, no longer even worthy of being connected with the stories of Wisdom and Power, of Zelda and Ganon.

It was this new thought that would set me out on my favorite task and coping mechanism: analyzing characters as a way to avoid analyzing my own self. So instead of doing my own therapy homework (sorry to my amazing therapist), I would pursue recontextualizing my understanding of Link, exploring my newfound enlightenment of his past of Ocarina of Time through his present journey in Majora’s Mask.

And in a surprising twist, this focus on therapizing Link to avoid my own healing proved to be deeply therapeutic in its own way.

An image of the opening text of Majora’s Mask.

Majora’s Mask is often framed as a story of Link’s grief over the loss of Navi, and of his efforts to help the strangers of Termina be happy. Instead, I now see it as the story of Link helping himself, coming to terms with all aspects of himself. Link is on his journey to find his way back to the identity that is represented by the Triforce, attempting to make it whole once again. And in doing so, he moves beyond it, forming a new identity for himself.

The journey allows Link to fully explore and accept all sides of himself, and allows us to witness his very personal journey, using it as a tool to better understand him, and even ourselves.

We’ll make sense of Majora’s Mask as a study of Link’s personal growth by exploring the following:

- How the Hero’s Journey pertains to Ocarina of Time and shapes the player’s understanding of Link throughout their first playthrough.

- The psychological concept of ego states, a model of thought and processing of events that we can use to dissect the actions and mechanics of Link in Majora’s Mask.

- The experiences Link undergoes in Majora’s Mask through the lens of ego states, and how they parallel and shed light on his trauma throughout his time in Hyrule.

- The transformations Link undergoes both physically and psychologically, and the unity of his selves.

- The identity of Link’s core self, how he uses this core self to heal and support others, and how his core self is strengthened after his personal journey.

As a disclaimer, I am using the dissection of Majora’s Mask as a literary and personal psychological analysis using a framework taught to me—I’m not a licensed therapist, and I do not claim to know the developers’ minds regarding official Zelda canon. My interest is in studying the content of the game in order to understand how it can allow players to make a new and deeper sense of our own identity, through the process of making a better sense of Link’s.

Part One: The Hero’s Journey and Ocarina of Time

Majora’s Mask draws its player into Link’s experience by showing them that they didn’t pay him the proper amount of attention in Ocarina of Time.

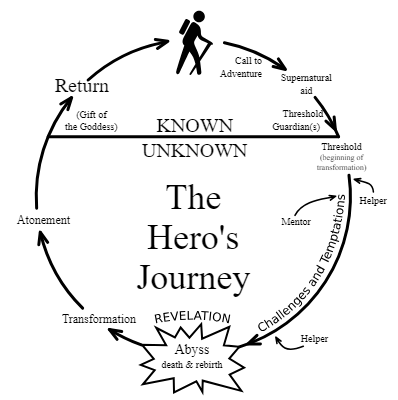

Ocarina of Time is widely considered to be a strong example of the Hero’s Journey, with strong examples of this including articles from Eduardo Ota and GaroXicon. Dan Hughes even discusses the topic in another With a Terrible Fate article. The Hero’s Journey, popularly known due to Joseph’s Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, is a common story template following a hero who sets out on an unexpected journey, faces trials, and returns home changed. Many stories follow this outline, from books such as Lord of the Rings, to movies such as Star Wars, and so it should come as no surprise that video games would take on this narrative device to tell captivating, strong tales.

A diagram of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. (Source.)

Link’s Hero’s Journey can be broken down as such:

The Backstory: Link lives his life in Kokiri Forest and is a somewhat isolated boy, never fitting in with his Kokiri peers. This isolation stems from his lack of having a guardian fairy, as well as his species—we know Link to be a Hylian, after all. We learn, some time later, that Link’s mother left him at the foot of the Great Deku Tree amidst the Hyrulean Civil War, and that he was adopted into the Kokiri children’s lives.

The Call to Adventure: When Link is called, he is a lonely, relatively lazy (and likely depressed) boy living in Kokiri Forest. He is then summoned by the Great Deku Tree, given the supernatural aid of Navi, and then sent on his way.

Link being awoken by Navi at the start of Ocarina of Time.

Crossing the Threshold: Link does this the minute he attempts to save the Great Deku Tree and fails. From there, a great trauma and change has occurred in Link, and he is unable to go back. He obtains the first of three Spiritual Stones, and goes on his way.

Challenges and Temptations: Link finds the remaining spiritual stones and meets various helpers and mentors in the form of Zelda, Rauru, Sheik, Ruto, and Darunia.

The Abyss and the Transformation: Link learns of his true history as a Hylian, and he is locked away for seven years, his child self dying and his hero form being reborn. In his transformation, Link fails once again, allowing Ganondorf to enter the Sacred Realm and steal the Triforce of Power. With this, Ganondorf takes over Hyrule, and this is what Link is set to atone for, working to seal him away once again.

Link encounters a grittier Hyrule following his transformation.

The Atonement: Finally, with the power of the Sages, along with the powers of Princess Zelda, he seals away Ganondorf.

The Return: Link returns home, a child once again, forever changed, forever altered under the weight of his adventure.

Link being sent to his child form at the end of Ocarina of Time.

Once the player recognizes, even subconsciously, that they’re taking a silent protagonist on the Hero’s Journey, they set aside questions such as the plot’s outcome and its psychological impact on Link.

The story takes a familiar form, and Link unquestioningly undertakes the player’s actions in pursuit of that story. As such, the player is free to focus on their own personal experience of playing the game. This allows the player to treat Link as a mere conduit to that experience, instead of his own character with a backstory and an arc.

This contrasts rather jarringly with Majora’s Mask.

A side-by–side image of Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask.

Time repeats itself, unlike the linear narrative of the Hero’s Journey. Three days are always going to go by, whether the player has Link interact with the world or not.

It’s on the player to decide what sequence should be prioritized, what tasks should be completed, as opposed to following the pre-destined path set for Link in Ocarina of Time. There is a level of active engagement from the player’s obligation to choose which events constitute the plot on each 3-day cycle in Termina, rather than following the rigid, linear plotline in Hyrule. And as the player reflects on which events to include per run, they access a different understanding of those events.

Because of the cyclical nature of Majora’s Mask, and the lack of clear Hero’s Journey template, the player of the game must be more engaged and aware than they were when playing Ocarina of Time. They do not know the common story beats, and thus have to find direction on their own. In this awareness, the player is much more likely to notice parallels between various characters, or pay closer attention to lines of dialogue. And what this awareness led me to is the fact that Link is undergoing an impressive psychological journey throughout his time in Termina.

Part Two: Ego States, and How They Manifest in Majora’s Mask

Without the structure of the Hero’s Journey, or a similar story beat structure, it can be easy to feel disoriented and directionless throughout Majora’s Mask. One may not know how to make sense of Link, despite recognizing the need to understand him to advance the plot. In my desire to better understand Link’s headspace, and by extension the story, I found ground in a psychoanalytical model as opposed to a literary model: Ego State Therapy.

Ego State Therapy, developed by John G. Watkins, was introduced to me by my own therapist, hence why it’s a topic that I am quick to apply to my own writings and perception of creative pieces—after all, why psychoanalyze myself when I could apply it to fictional characters? Ego states were explained to me as a conceptual model for how a person might relate to the various parts of their own identity, or label the various voices in their head.

Good Therapy describes ego states as “the amalgamation of several distinct people or egos, such as the wounded child or controlling personality.” These distinct egos are representations of facets of an individual person. While some describe it as a family of selves, I personally associate it with a metaphorical office boardroom: a round table with various chairs, with each ego state having a spot at the table.

A standard boardroom. (Source.)

It’s important to note that ego states are not “multiple personalities.” When relating to oneself through distinct ego states, there is no full switch, there is no drastic change in behavior, and there is no lapse in memory of events. Instead, each person has a “core” identity, which exists as the base individual prior to, or without, the facets. This is the person that the ego states formed within, traditionally to protect the core self. For example, I, writing this, am my own core. I am sitting at the head of my internal office room table, and I am what created all of my ego states sitting around it. Even if I struggle to be in touch with myself at times, I’m aware of the elements that make me myself, and, more importantly, which of those elements come from my ego states.

Then, at the other seats around the table, there are the ego states. While Good Therapy breaks it down into four types of states, I’ll simplify it into two:

Conflicting ego states work against the core, either by causing emotional reactivity, conflicting with other ego states, or simply being useless to the core. Conflicting ego states can be triggered by an endless list of things, from someone speaking in a particular tone to dropping and breaking your favorite mug. Often, when an ego state is in conflict, you have little control over when they surface and how long it takes to regain control of your thoughts.

Normal ego states are healthy ego states that are “openly acknowledged, not in conflict, and not maladaptive.” Normal ego states may be triggered by the same triggers as a conflicting ego state, but will not be as reactive or intense, instead making the core aware of a discomfort, offering solutions, and then taking a step back. They can also be accessed and summoned with some inward thought, allowing the core to connect with these voices as it sees fit.

Normal ego states work in tandem with the core, and can be as useful as taking on and off a transformation mask. They can offer a deeper awareness of oneself and one’s triggers, and give a deeper array of emotional skills and coping mechanisms.

Link with two of his transformation masks.

Ego states are typically formed or strengthened out of traumatic events.

You might create a form of yourself that is able to cope with childhood abuse, pushing aside your feelings of sadness and fear until it becomes its own voice. You might have a perception of yourself as a productive, hard-working individual that helps you in some cases, but is also the voice that calls you to neglect your personal needs in the name of being “productive.” You might have rage from your youth, a voice that burns hot and lashes out, filling you with glee when you act on it, but filling you with regret as the voice fades.

When these states are unidentified and misunderstood, it can leave a person lacking a sense of self. If a person were to unknowingly have a “productive” ego state, mixed with a “withdrawn” ego state, and perhaps with a “fearful child” ego state thrown in, there would be a significant amount of conflict in the day-to-day.

From personal experience, she would struggle deeply with taking actions to better her life, as the productive ego is pushing her to do it, criticizing her if she does not, and triggering the child ego as she is being reprimanded. The child ego may want to perform well for the sake of praise from others, but it may be fearful of trying new things without help. This would all be fodder for the withdrawn ego, as she would take this conflict as an excuse to not even try, choosing to rest while sinking deeper into herself in a vicious depressive cycle. To top it all off, the core self would struggle coping with the shifting wants and needs, unsure of her genuine needs and what would help her break this cycle.

Mido bullying Link at the beginning of Ocarina of Time, highlighting his lonelier childhood.

We can also see how ego states can harm relationships. Were one to have been abandoned as a child, they might have formed an ego state that clings to romantic partners, taking even the slightest tone change as a sign that they are leaving. Their more productive, pragmatic ego state might welcome the chance, believing they could do better, and they may even have a self-destructive ego state that urges their partner to leave due to erratic behavior. This combination would then be incredibly harmful to the core self, as well as the partner, being caught in a vicious tug-of-war with only one person.

These are examples of conflicted ego states at its worst. Any sort of emotional understanding is thrown out the window when your emotions are changing on a confusing, uncontrollable whim. You can find yourself going in constant spirals, unending cycles, until you have absolutely no idea who you are or what to do.

It takes a lot of work to connect with conflicted ego states. For the most part, you cannot just choose to ignore them: if you’ve ever been told to “just stop feeling sad” or “just cheer up,” you’ll know how disheartening that can be to hear. In contrast, you also can’t only listen to the conflicting state; that will typically end in a negativity spiral.

And so, at least in my journey with my own ego states, the key work has been in “normalizing” the ego state. This is done through identifying the states, listening to them as they arise within me, understanding where they are coming from, and ultimately deciding from my “core” self if my ego state is working to help me or hinder me. I listen to my inner child when I require some self-care and nurturing, but I also know when she’s throwing a bit of a tantrum. I listen to my more emotionless productive self when I need to overcome a particularly difficult work hurdle, but I also know when I’m using work as a method of avoiding my feelings. And I listen to my more nihilistic self when I find myself fantasizing instead of working towards my goals, but I don’t let her send me into an “everything is meaningless” spiral.

In simpler terms, I ask myself how I can utilize these masks of mine to enhance myself, as opposed to allowing the masks to consume everything I am. I ask how these more toxic relationships with my selves can become healthy, thriving ones that empower me. I ask myself how I can turn a subconscious limitation into a conscious form of agency.

Link’s transformation masks in Majora’s Mask. Top Left: Zora. Top Right: Fierce Deity. Bottom Left: Goron. Bottom Right: Deku.

As Link undergoes his personal journey in Majora’s Mask, he is not only encountering new individuals with striking parallels to his own, but also new sides to himself, externalized as these souls. He is encountering his own ego states.

Link’s lost, lonely, inferior sense of childhood is represented through the Deku Child Mask.

Link’s constant need to succeed, save, and fight is represented through the Goron Hero Mask.

Link’s sense of love, caring, and providing is represented through the Zora Singer Mask.

Link’s expectations and delusions are represented through the Fierce Deity Mask.

Part Three: Majora’s Mask as an Examination of the Events of Ocarina of Time

Sometimes, we can only clearly see how we’ve formed our own identity through time and distance. After all, hindsight is 20/20, as many of us have experienced. This time and distance is precisely what we offer Link in the events of Majora’s Mask.

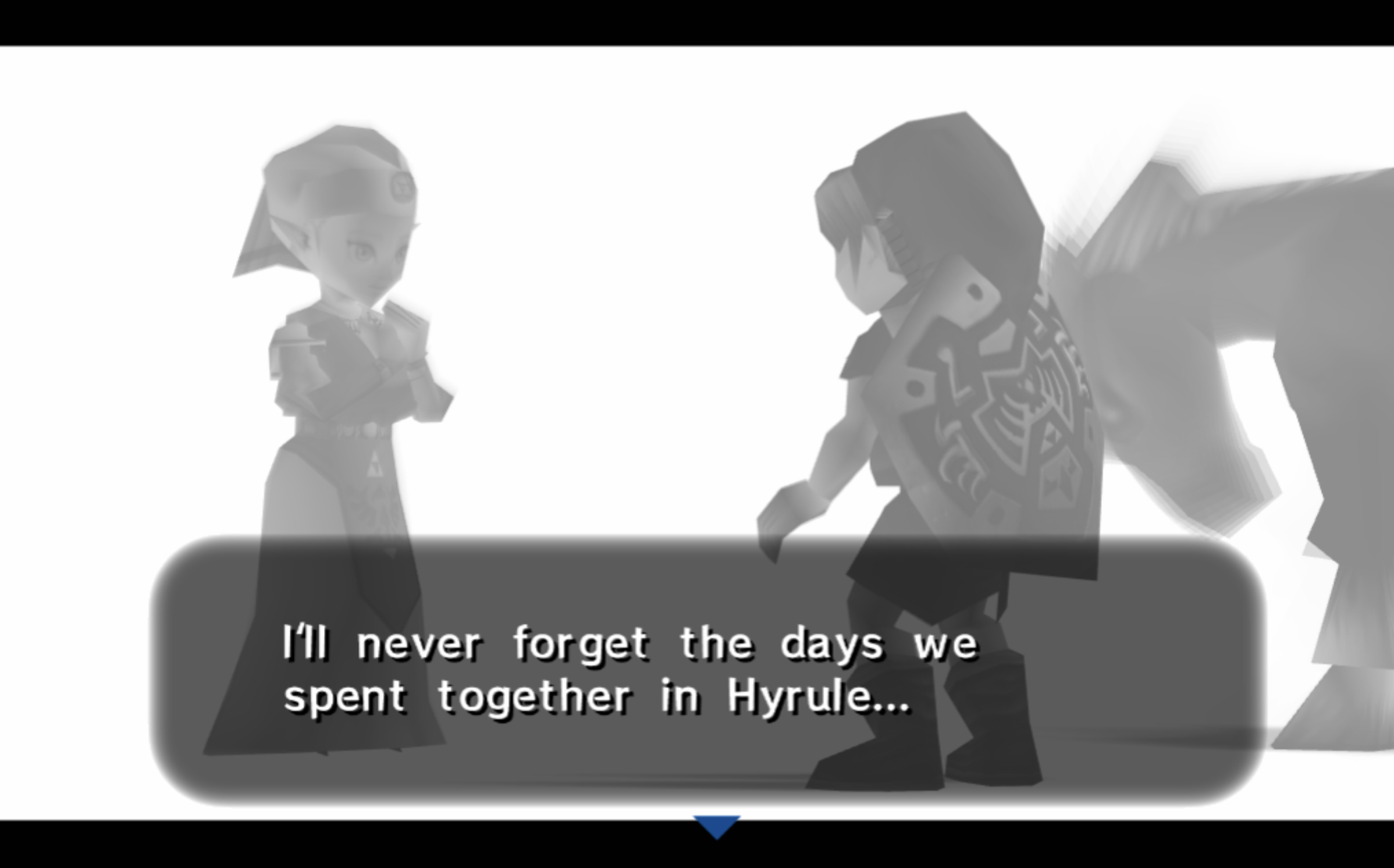

A flashback of Link and Zelda, post-Ocarina of Time.

If I could, I’d like to ask you to take a moment and sit inside yourself. Remember being younger, that age within late single-digits, early double-digits. That sensation of the world being at your fingertips for the first time: yours to explore, to conquer, but also yours to fail in. Can you remember the first time a dear friend told you they didn’t like you anymore? Perhaps it was a move, a change in school and setting, shifting the entire world under your feet, or perhaps the person asking you out on a dare in middle school really did give you trust issues in your future dating life.

Childhood events affect us deeply, at our core. We repress them, we relive them, we even fund entire careers of therapists to help us work through the darker parts of these impactful times. Children are impressionable, children’s minds are malleable, and no matter how rambunctious, strong, or courageous the child, they are delicate.

It’s in this delicate state that ego states form. We find coping mechanisms in our younger years that help us navigate the confusion of adult struggles in a younger mind, and as we grow, these coping mechanisms serve us less and less. The moldability forms unhealthy models and core beliefs that follow us well into adulthood, often unbeknownst to us until it is too late.

And that moldable age is exactly when a certain Hylain outcast child is confronted with the struggles of being the Hero of Time.

Link standing in the Temple of Time.

We may not pay such a mind to those struggles in Ocarina of Time. As discussed, the use of the Hero’s Journey allows us to focus on our own personal experiences of the game, taking Link for granted as a silent protagonist.

But because of the lack of a familiar structure in Majora’s Mask, we look more closely at our character in order to understand his wants, needs, and what he’s actively going through. And once we do so, we realize that his nature as a silent protagonist makes it difficult to get clear data on his thoughts and feelings. Therefore, it’s on us to reflect on our shared experiences with Link in Ocarina of Time, as well as the storytelling in Majora’s Mask, and empathize with how it must have been for him to bear the burdens of the journeys we previously took for granted.

Within Majora’s Mask we can look at the transformation masks, the souls they stem from, and their mechanics to garner a deeper understanding of Link and how he perceives his adventures. In so doing, we can derive narrative parallels between the main phases of Link’s journey in Termina and the conflicting ego states he must confront and normalize.

At the start of the game, these ego states exist in a conflicting state, unidentified by Link and the player. But throughout the course of Majora’s Mask, we are helping Link identify his ego states and normalize them. We do this by guiding him, supporting him by being familiar with him and his trauma thanks to our time spent with him in his journey in Ocarina of Time.

Part Three A: The Deku and Link’s Youth

Link encountering the lost Deku child’s body.

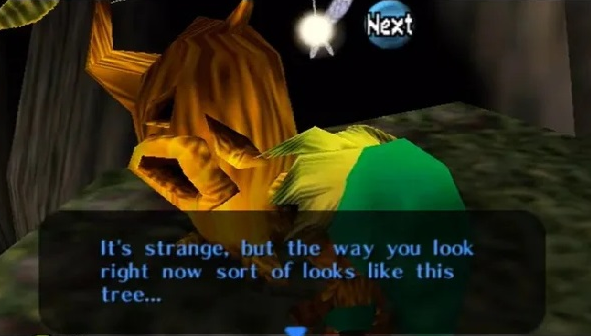

When entering Termina, Link is turned into a Deku by the Skull Kid, without Link’s input or agency. In time, we come to learn that the mask contains the soul of a lost Deku child, the young son of a butler who strayed a little too far from home and met an untimely end.

This parallels Link’s own childhood. In Ocarina of Time, much of that childhood is expressed through quick lines of dialogue and subtext. His sudden loss of childhood is a tragedy, one understated and unexplored in his adventures as a great hero. He was born amidst a war and was abandoned by his mother against his will, and he was deemed an outcast through no fault of his own. This sense of loneliness and inferiority was created by something completely out of his control, similar to his initial transformation into the Deku.

Left: Deku Link. Right: Child Link.

His time as a Deku Scrub is incredibly telling of how he feels in his child form: he is small and ineffectual. He has only the spin attack and a bubble, mirroring his slingshot and wooden sword that do very little damage. He is attacked by dogs, unable to leave town, unimpressive to the children of Clock Town, and all around ignored and underestimated—very similar to how he was perceived by Mido and the other Kokiri children. His lack of power also parallels Link’s time walled off in Kokiri Forest; sequestered in a foreign place, left without the agency or strength to leave or alter his own world.

Deku Link demonstrates his bubble shot to Jim, one of the children of Clock Town.

The Deku Mask, representing Link’s lost child ego state, is one filled with fear, helplessness, and isolation.

And what’s worse, Link is initially unable to remove it.

No matter how much he may want to, or how uncomfortable it is for him, he is forced to sit within this ego state.

Deku Link observing Clock Town.

This act of forcing the player through a three-day cycle in which Link is stuck in this Deku child’s form allows us to feel the same loss of control and helplessness that Link himself is feeling. We are stuck for three days in Link’s lost child ego state, formed in the prelude to Ocarina of Time.

This cycle of time might feel slow, even pointless to a player. At times, when picking up Majora’s Mask for a replay in the past, I’ve wondered how best to use my time during that period. I’ve danced with a scarecrow to advance time, fallen asleep to an old woman’s stories, even glitched outside of Clock Town’s walls to advance the plot and maximize the use of my time.

But in this latest playthrough, I remembered something. When considering one’s ego states, it serves one well to listen and accept the state, instead of just ignoring it. So, I was compelled to simply explore as Link, and as such, explore Link.

Throughout those three days, Link has the chance to fully connect with his lost child.

He has those three days to fully understand this ego state. Through the player’s actions, he befriends the reluctant Bombers Gang, accessing their hideaway. He helps another Deku secure a gift for his wife, and he restores the Great Fairy back to normal. And above all, despite his form, he perseveres and stands against the Skull Kid on the final day.

An important element to this: Link cannot afford to fail at this self-reflection. If he does, the moon falls, and Termina is wiped out. The stakes are higher for Link to come to terms with his lost child, and due to this, I believe this ego state to be one of his most damaging in its conflicted state.

In Part Two, I explained how damaging conflicting ego states can be to us, and to our relationships. There are some ego states that can be more damaging to us than others: those that hinder our abilities to make relationships, versus those that simply cause burnout once in a while, for example. In Link’s case, his lost child is actively demolishing his sense of self and accomplishment, and he is consumed by it, unable to stop his spiral. It is destructive; it influences his entire being and his relationships; it is the one that is rooted the deepest in him. Because of this, it is the ego state that is most important for him to overcome in order for him to truly begin his healing journey.

If he cannot overcome his lost child, he isn’t ready to overcome the rest of his journey, and as such, the game ends.

However, on a successful playthrough, Link perseveres. Once Link is reminded that he has overcome being the lost child once before, grounded as he remembers his time with Princess Zelda, he is able to accept that he is more than just that ego state. He returns to himself, his core personality, with a normalized ego state under his belt. With that, he is able to remove the mask, waving his lost child self farewell for now.

Link waving the lost Deku spirit farewell, giving birth to the Deku Mask.

Part Three B: The Goron and Link’s Renown

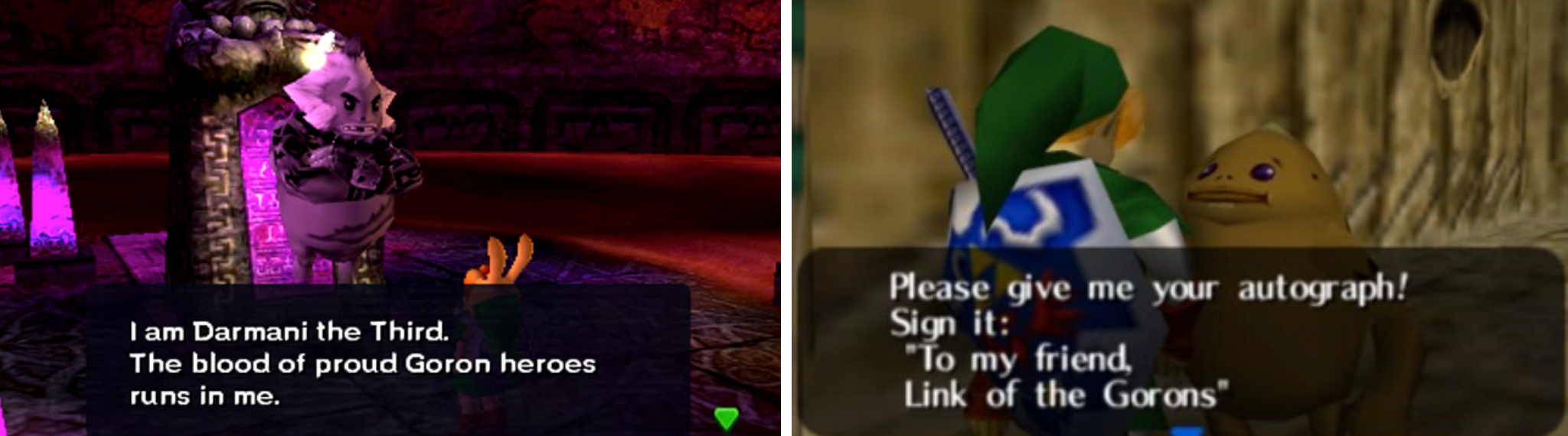

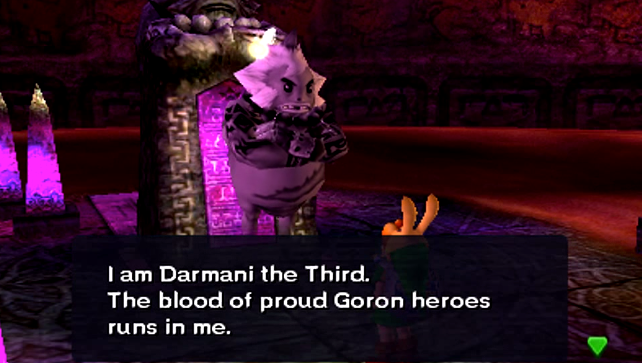

Left: Darmani, the Hero of Gorons in Majora’s Mask. Right: Link, the Hero of Gorons in Ocarina of Time.

As we venture through Termina, Link encounters the spirit of Darmani the Third. It is important to note that unlike the Deku mask, Link does not take on the next ego state unwillingly. He encounters a city in need of help, and a lost soul.

This soul is the Goron Hero, Darmani the Third. He is a proud, vain man determined to go on saving his people. He has achieved the highest honors and praise, with his grave being the most ornate of all the Gorons’. In death, he is restless, distraught that he cannot go on saving his people from the endless winter, unable to accept that it’s no longer his duty. He begs Link to revive him, and when that fails, he begs Link to heal his sorrows, and leaves Link with his unfinished duties.

Darmani the Third’s introduction in Majora’s Mask.

Link’s first true taste of public heroism, along with external pressure and expectations, was not as the Hero of Time, but rather as the Dodongo-slaying hero of the Gorons. This act is the first grand success he has, replenishing their food source and killing a monstrous beast. This feat is so great that even 7 years later, Darunia has named his son after the Legendary Hero.

While Link was not forced into confronting this ego state, as he was the child state, there is importance to the timing in which this ego state is introduced.

Shortly after finding comfort and peace with his child ego state, Link enters yet another realm in need of saving: the Goron Village. Reminded of his triumphs after preventing the moon’s fall and saving Woodfall and the Deku Princess, Link is beginning to fall into an old identity, and another ego state in conflict.

The Hero.

The Hero of Time.

The lost child is a more obviously conflicting ego state—fear is viewed as a negative emotion, after all. But a sense of heroism (while brave and kind) can fuel recklessness, and an obsessive, unfulfilling impulse to always be saving. This ego state wouldn’t allow Link any sense of rest, reprieve, or above all, safety—should he never come to terms with its identity.

After failing to save the Great Deku Tree in Ocarina of Time, Link would likely feel a great rush at his first grand success upon saving the Gorons from starvation. As such, it is likely that Link’s first sense of heroism and praise was addicting, and he would continue to chase that high throughout his adventures, no matter how reckless or strong he may need to be in order to achieve victory. It is fitting that his hero ego state, shown through the Goron’s mechanics, would pack a powerful punch and race with little control across perilous cliffs.

Goron Link rolls perilously along the narrow path to Snowhead Temple.

Link was not forced into this ego state (or mask) as he was that of the Deku: he did ultimately choose to be a hero… somewhat.

After Kaepora Gaebora explains to Link his path as the Hero of Time, he asks Link if he understands his destiny. The player can give an answer of “yes” or “no.” Choosing “no,” however, only causes the owl to repeat himself until Link says “yes.” To Link, at this point in his journey, he is already addicted to the rush of being a hero, determined not to fail in the way he did with the Great Deku Tree, determined for his great destiny.

The conflict comes not from being his hero self, but rather learning that he must eventually come to terms with taking off the mask.

After all, as I’m learning with my creative side, I cannot leave that engine running 24/7. Every soul, no matter how heroic or strong, needs to learn how to take a break.

Darmani dies a restless soul, tormented by the fact that he will not be able to save his people one last time. Yet there will always be another fight, another mission, another battle, and this is a fact that Link must slowly come to terms with. If he chooses to only be The Hero, as Darmani has, he will die a restless spirit, and forever be plagued by unwon battles.

Darmani mourning his own death.

As Link heals Darmani and allows his spirit to rest, he offers a short nod to Darmani, one of understanding and respect. It’s a gesture that’s later mirrored in his final salute to Captain Keeta in Ikana. He is saluting farewell to fallen soldiers, and in so doing, he is respecting that not all battles can be fought—that one must eventually remove the mask and moniker of The Hero.

And with the recognition that the hero ego state is not all he is, he normalizes that ego, returning to his core self with one more tool under his belt.

Link saying farewell to the Goron Hero Darmani.

Link saluting Captain Keeta farewell.

Part Three C: The Zora and Link’s Love

Left: Lulu and Mikau. Right: Link and Ruto.

Once Snowhead Temple has been cleared, Link reunites with a loved one he believed was once lost: his trusty steed Epona. It’s not a stretch to imagine that this reunion would be a moving one for this silent protagonist, as he and Epona were traveling together for some time after the events of Ocarina of Time, her being his only companion in this journey prior to Tatl.

Thus, finding her again would reveal joy, hope, and his third conflicting ego state: his love.

Link’s love is paralleled in the soul of Mikau the Zora.

Mikau is a loveable, renowned guitarist. He died appreciated by his peers, adored by his fans, and genuinely loved by his girlfriend Lulu. He died as an act of love and devotion, entering the Pirates’ Fortress to attempt to save the stolen eggs of his love. It’s his love that costs him, in the end, and he dies in vain.

Link enters Great Bay Coast, and finds the Zora Mikau half-dead and floating in the water. Link then saves him… only for him to immediately die. Link then buries Mikau, erecting a gravestone and offering a moment of silence to the fallen musician.

Link offering a moment of silence to Mikau’s grave.

How beautiful that Link’s loving ego state is represented through the soul of a musician, when the ocarina is such a core part of him.

How utterly morbid, that upon the meeting of his loving ego state, it immediately dies at his feet.

Love is not an inherently negative trait, and as such it may be a stretch to understand how it is conflicting. It’s possible, however, for love to create conflict in the psyche of someone also bearing the ego state of a lost child.

Love is likely a strong trigger for Link as the trauma he primarily faces is loss. He had to reconcile with growing apart from his childhood friend, he was left by Ruto due to her becoming a Sage, and he was wordlessly left by Navi, for whom he continues to search all this time after.

Link parting ways with Saria as he begins his adventure in Ocarina of Time.

To understand the conflict between a lost child and love more granularly, let’s examine the case of Saria through the eyes of the ego states. Link, who has been ostracized from other children growing up due to being different, finds a deep connection in Saria, who accepts him for himself. His lost child would cling to her, her being the one person who makes him feel good about himself, loved and protected. His child ego would effectively crave her affection, and would be completely shattered when he aged and she didn’t, thus causing their bond to weaken. His lost child would be screaming that they’re being abandoned.

And as this case generalized into the pattern of Link’s relationships across his adventure, his lost child would grow to assume that to love is to be left.

Navi flying away from Link at the end of Ocarina of Time.

There is a strong, negative connotation with love that would immediately trigger his sense of abandonment, which would cause a strong reaction in the lost child ego. Therefore, even if it’s not intrinsically negative, the love ego becomes damaging to Link because of its intrinsic conflict with the lost child ego.

This sense of negativity in relations is represented even more through Mikau’s relationships, when Link interacts with his friends. Lulu is mute (understandably, as her own children have been ripped from her by pirates), his band is in conflict: all of his relationships require fixing. Link likely shares the sentiment, seeking not to forge new relationships, but instead attempting to hold together the fading ones he currently has.

The mechanics of the Zora Mask underscore how dangerously magnetic love can be. While Link’s Zora form can effortlessly swim through perilous waters, it can also be a difficult mechanic to control once you get going. Much like in life and love, you need to follow the current and go where the water takes you, even if it is a piercing heartbreak at the end – you cannot swim against it. Even with that risk, love can be as electric as the shocks that Link can emit in this form, and the metaphor illustrates how Link perceives these strong emotions: as fluid and damning as a current, and as electric and fatal as a shock.

Zora Link swims and shocks his way through the Great Bay Temple.

It is only when Link succeeds in helping the individuals of Great Bay, but decidedly not lingering on them, that he normalizes his loving ego. While Link’s relationships are clearly important and vital to who he is, they are not all that he is. He is not defined solely by Navi, Zelda, Saria, Tatl, or anyone else he meets. He is still himself, his core, and he no longer relies on past relationships to define him in his entirety.

Part Three D: The Fierce Deity and Link’s Expectations

Left: Fierce Deity Link. Right: Hero of Time Link.

This final ego state Link encounters is one that stems from a good place, but over time comes into conflict with the core. It is obtained after he has gone through many cycles of healing, found after completing every single mask sidequest in the game. This ego state is that of the perfectionist. This ego state is Link’s internal expectations, the voice urging him to complete every task, break every pot, and save every person.[2]

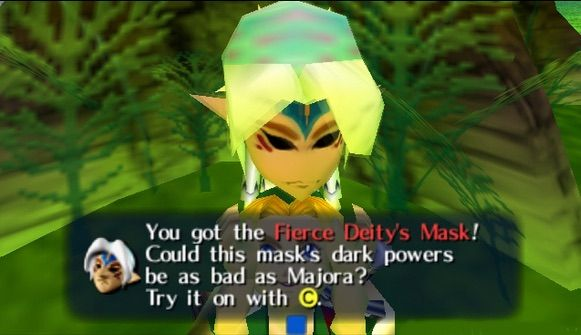

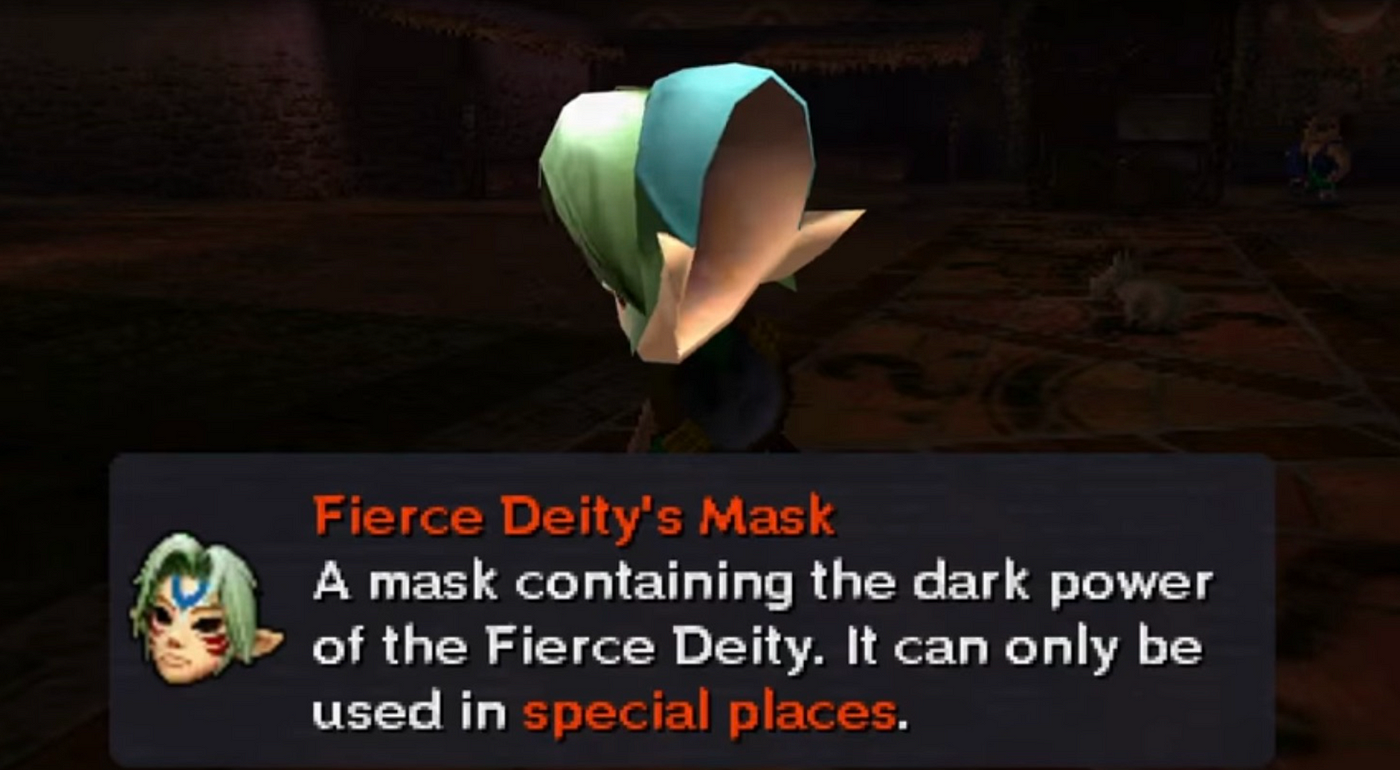

The Fierce Deity is presented as an ominous figure, with very little said about it throughout the game. It is a very powerful mask, and once it is given to Link, it can be examined to give the following messages: “Its dark power can be used only in boss rooms” and “Could this mask’s dark powers be as bad as Majora?”

This invites the question: what element of Link’s could be as dark as Majora? What could consume him and inflict pain to others? We must go back to his adventure in Ocarina of Time to answer this.

Obtaining the Fierce Deity’s Mask.

Link was given a grand task at the start of his adventure, one that he had pummeled into his head at every moment: he was to be the Hero of Time. He was to be a grand savior and defeat the evil Ganon. This was his path, his fate, his destiny. And over time, Link would begin to perceive himself in the way we, the player, did in his initial Hero’s Journey: not as a human (or Hylian) person, but as a Hero.

We see how far this determination to be a hero has warped through the mechanic in which we obtain the Fierce Deity’s Mask: healing every individual’s problems within Termina.

A complete collection of masks within Majora’s Mask.

Link is fueled by the fear in his lost child ego, the obsession in his hero ego, and his kindness in his loving ego: he must save everyone, and he must be perfect. He feels that he must be a deity, carrying the hopes of all he meets, soothing all of their worries, and winning every battle.

The final trauma which Link must work through is expectations, particularly his own. There is a danger in “shoulds.” While having goals, aspirations, and ambitions is incredibly healthy and motivating, when they morph into expectations, they become slightly more damaging. If one’s self-expectations are too high, not only does one not allow oneself room to grow, but one also doesn’t allow oneself room to fail, to learn, to hurt, to be human like everyone else.

The idealized self, the Fierce Deity, can be a very dangerous ego state when left unchecked. Link cannot be this ego consistently, mechanically and emotionally. It would take a toll on him because while he may wish to be this form all of the time, it’s not who he is. It’s not his core self.

There is, however, another element of this ego state’s introduction that is of note: Link immediately recognizes that this could be dangerous for him.

The description of the Fierce Deity’s Mask indicates its scarce usage.

This is shown through the warning text, in which it is noted that this mask’s dark powers could rival Majora’s. From the description, Link appears aware that this is what consumes him in the same way that Skull Kid’s rage ego consumed him through Majora’s Mask. Link is aware that he cannot be the Fierce Deity—or the Hero of Time—forever.

He accepts this awareness through the game’s mechanics, in which he is cautious as to when he dons this ego state. He chooses to access it only in boss fights, when the situation is dire and when he truly cannot afford to fail. He normalizes his ego state by accepting that it is only one for extraordinary circumstances, and one not to be consumed by.

And it’s with acceptance of this that he is able to remove the Fierce Deity’s Mask and return it to his arsenal, ready and waiting to pull out when the right time calls for it.

Fierce Deity Link facing off against Majora’s Mask.

Part Four: Transformation and Unity

Regardless of the mask Link is wearing, or how he obtains it, there is a consistent element in the transformation process.

Pain.

Link putting on each of the transformation masks, in pain.

That’s not to understate the obvious—he’s physically transforming into a completely different being, of course it’s painful. But if these masks are in fact to be recognized as various ego states of Link, it also makes complete sense that getting in touch with these sides would be unfamiliar, uncomfortable.

Self-reflection and discovery is difficult, and it is painful. While it gets easier over time, it is not something that ever really goes away. And as such, Link’s consistent pain when entering a state is one that strongly reflects how hard it can be to work on and with oneself.

So then, what’s the point? If it hurts, why do the work? Why not spend the entire game as Link’s core? Why might one take the time to get in touch with one’s selves?

From personal experience, I can say that without a doubt, regardless of the struggles I have with my various ego states, I am one hundred times stronger and more at peace when I am unified with my selves. When I listen to all voices at my round table, not actively working to repress them, their voices don’t linger: rather, they are heard, accepted, and allow me to move forward as my core.

This is where I’d like to take the time to examine Ikana Canyon, and the Stone Tower Temple, the area that is the most important for Link’s growth throughout this entire process. This may seem hard to believe, as it is primarily a barren desert with some funky skeletons. However, there is a key factor here: you do not receive a transformation mask upon entering this area.

But before I jump any further into that, let me first make a nod to our sponsor: the Clock Town Milk Bar.

Link in all his forms, performing at the Milk Bar.

There are some whacky parts in Majora’s Mask—elements of the game that feel out of place, even in a world that has a falling, crying moon and time travel. The one that always struck me was the soundcheck Link does in the Milk Bar.

This side quest is very out-of-the-way. You need to have acquired all of the transformation masks, as well as the Romani mask, before completing it. Otherwise, it’s a very simple task: get onstage and play your instrument wearing each of the transformation masks, creating a one-man/four-man band for the Indigogos’ soundcheck.

What’s weird about this, you ask? Well, it’s the only instance of all four versions of Link existing in the same space at the same time, excluding the use of the Elegy of Emptiness. And even with the Elegy, those are statues—this soundcheck is the only instance of all versions of Link existing live, together, in one space.

The majority of Link’s special skills come from using his ocarina, or conducting, or playing a harp; music is an integral theme throughout many of the mainline Zelda titles. Which is why I find it very beautiful and very fitting that the only time all of Link’s ego states are in perfect sync is the one instance of playing music with them, creating a beautiful melody that brings tears to the members of the Milk Bar.

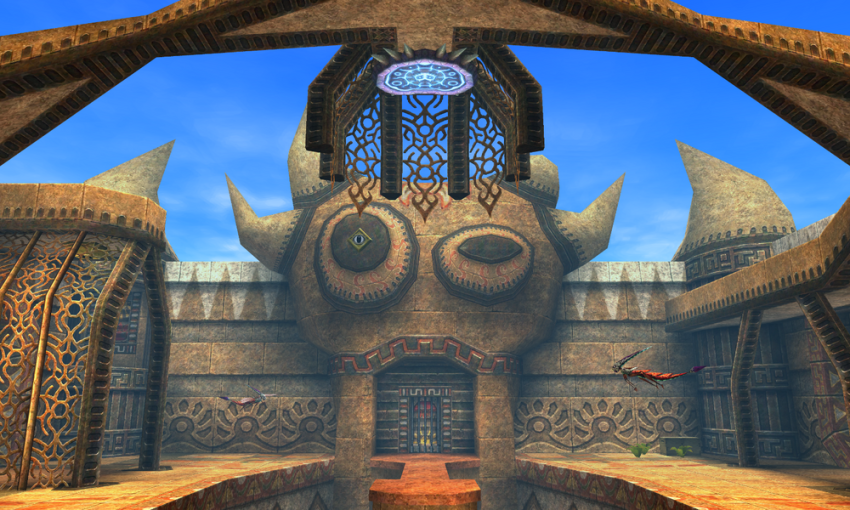

This sense of harmony and self is what the Stone Tower Temple exists to solidify.

The entrance to the Stone Tower Temple in Ikana Canyon.

Ikana Canyon allows for the most important mask of all to be appreciated: Link’s Mask. He does not gain a new ego state, but rather has a period of isolation in which to better come to terms with himself. Stone Tower does not rely on one of Link’s ego states to survive, nor does it offer a new one—it relies on all of them working in harmony to ascend.

By the time Link enters the temple, he has come to terms with his ego states. He is able to access each form at will, connecting with their abilities and calling on their strengths when the situation calls for it, all while retaining the ability to return to his core whenever he desires.

There is proof of this in two key elements: his ability to complete the tower without relying on one particular mask, and the return of the Triforce symbol.

The Triforce symbol on the bottom of blocks in the Stone Tower Temple.

This image has been a large point of controversy across the Zelda community, sparking theories, polls, and more. However, through the model in which we’ve been working, particularly in terms of Link’s journey to become whole, this symbol has one very clear meaning to me:

The Triforce is no longer shattered. Link is once again confident, whole, and feels himself worthy of the Triforce of Courage. The Triforce’s presence on the underside of the statue, however, points to me that Link is no longer as inclined to present this as his whole personality. It’s a part of him, his Hero of Time self, but it isn’t his face; it isn’t his whole.

Towards the second point, Link utilizes various ego states to complete this temple, while still retaining his core self.[3] He’s also able to leave behind each ego state’s form, its essence, and step back from it, examining it for what it is. He accepts their use in the moment, and then moves forward without clinging to them as a part of his essence.

All four of Link’s statues formed by the Elegy of Emptiness.

Something important that I’ve learned amidst my journey with my own ego states is how to identify them, how to call on them when I need them, and how to step back, look at them, but still make my own decisions. It’s about harmony in the boardroom: listening to every voice when needed, but still taking control at the end of the day.

This is what Link needs to do in the Stone Tower Temple. In fact, more often than not he is in his core form, choosing to swap between masks merely as placeholders or for quick tasks.

So, standing apart from all facets, all additional voices, the Stone Tower Temple poses the question of what voice our so-called silent protagonist has. Who is Link? When he is stripped of all of his transformations, his titles, what remains?

In the events of Majora’s Mask, I come to respect not Link the Hero of Time, but rather Link the Healer.

Part Five: Link’s Core Self, and the Moon

Link playing the ocarina.

The first song Link comes to learn that is unique to this journey in Termina is the Song of Healing, one used to heal pained spirits. Link, throughout his entire journey in Majora’s Mask, goes out of his way to ease the troubles of all the residents of the land. Even if the deed is small, even if time insists on erasing his efforts, Link focuses on the individuals.

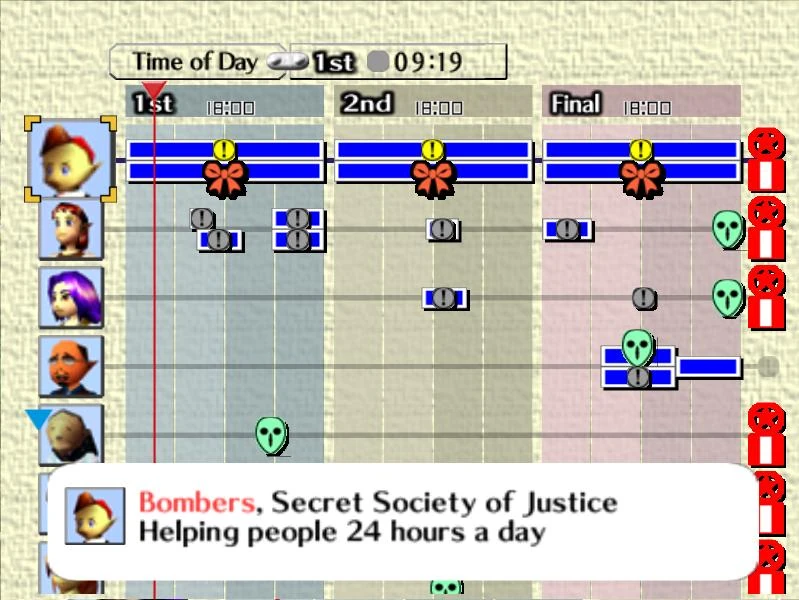

We keep track of these deeds through the Bombers’ Notebook.

One of Link’s first actions when returning to his core self at the start of the game is to acquire the Bombers’ Notebook. This notebook allows the player to keep track of every individual within Termina, their locations, and if they have been healed yet.

The Bombers’ Notebook in the original Nintendo 64 version of Majora’s Mask.

While it’s a useful tool, it’s significant to Link as one of the driving forces to understanding the world he’s in, a world that is a representation of his own psychological journey.

Before video games had clear game guides that could be Googled at the slightest hint of confusion in where to go, you had to rely on the game to guide you through itself. The constant guiding force throughout Majora’s Mask is this notebook, allowing you to explore routes you have yet to see, identifying damaged souls in need of healing, and presenting a path for Link and the player.

It is meaningful that this driving force for the player mechanically is Link’s personal driving force: his desire to help.

The Bombers’ Notebook in Majora’s Mask 3D.

And in helping others, in healing others, he only comes to understand himself more, evident by obtaining smaller, less transformative masks throughout the game.

Perhaps he recognizes his lightness on his feet when collecting the Bunny Hood. Perhaps he respects the Gorman Brothers’ tears and feels comfortable crying his own when wearing the Troupe Leader’s Mask. Perhaps looking at the Couple’s Mask is reinforcement to Link of his own ability to love deeply.[4]

As Link helps and understands others, he helps and understands himself. That is who he is: a helper, a healer. This does not erase that he is a scared child, a relentless hero, a passionate friend, or a frightening god, but it reinforces that those elements of him are not all that there is to him.

Over the cycles of Majora’s Mask, Link becomes unified, in sync with himself and all of his normalized egos. There is a poetic sense to how internal battles are fought: they are long, they are hard, and they are continuous. They crop up frequently, at times feeling as repetitive as one might feel if stuck in a three-day cycle. But with every pass through the cycle, with every small internal victory, the following victories grow easier.

After all, in any therapeutic process (at least those which I have encountered), healing is never linear.

The clearing in the Moon.

It is this growth that allows him to move forward into the final area of the game, the one that had been looming over him since his arrival: the Moon.

We know the Moon in Majora’s Mask to be a very frightening visage, threatening the ruin of all things. However, there are hints to Link’s psychological journey in its very being, too.

Left: the N64 Moon. Right: the 3DS Moon.

The moon, in various spiritual beliefs, often has a connotation of inner work. In terms of tarot reading, the card represents the inner work, things hidden in the subconscious. In astrology, your moon sign reflects your emotions, fears, longings, and dreams—once again reflecting the inner self. It’s even believed by some that the phases of the moon bring forth various hidden emotions to the surface, once again being a symbol of the true self.

Interesting, then, that on the exterior, the moon in Majora’s Mask is so frightening. This goes hand in hand with Link’s pain with the transformation masks: he views his self-reflection as frightening, painful.

Thus, it is all the more impactful when he stands up to this fear, entering his final battle within the Moon. Link is given one last test: a fight not with a villain, but his own questions, doubts, and fears—a fight with his inner self.

Inside the moon is a bare-bones parallel with Kokiri Forest: a tall, towering tree, surrounded by running children.

The Moon Children.

Each of the running children wears a mask of one of the bosses fought throughout the game. Each greets Link with a cryptic question, before sending him to play a “game” relating to each of his transformation masks. These questions each target a particular trigger of each of Link’s ego states, testing him to ensure he truly has achieved inner growth.

The Odolwa Moon Child, corresponding with the Deku Mask and Link’s child ego state, asks Link if his friends truly see him as a friend as well.

The Odolwa Moon Child.

This question relates to the very nature of friendship, and is one integral to Link’s early years. Living forever as an outcast amongst his so-called peers, he likely asked himself this very question many times, calling into doubt the nature of his friendships with Saria and the other Kokiri children.

This question would only persist in his later childhood years, the years when Link would forge a bond with Princess Zelda through his dreams and destiny, only to have minimal interaction with her, and forming a deep bond with his fairy Navi only for her to fly away.

We see Link’s growth as he easily navigates this portion of the Moon’s playground with the help of his normalized child ego state. He is no longer frightened and alone, but rather trusts that his bonds will give him strength.

We next see the Goht Moon Child, corresponding to the Goron Mask and Link’s hero ego state. They ask Link what makes him happy, and if that makes others happy too.

The Goht Moon Child.

It’s not a long shot (or a hoookshot) to imagine that Link once questioned this about his own heroism. He has been met with sorrow and disapproval after tackling the issue of the Great Deku Tree in his early adventures. He’s left thankless after his adventures as the Hero of Time. And due to the nature of time in Majora’s Mask, many inhabitants of Termina never know that he has helped them.

Link may have once been deeply hurt by this thought that his heroism might not always positively affect the lives of those he saves. However, his newfound assuredness and confidence in himself and his deeds allow him to roll along into his next inner conflict.

The Gyorg Moon Child corresponds with the Zora Mask and Link’s loving ego state. The child wonders what the right thing is, and if the right thing makes everyone truly happy in the end.

The Gyorg Moon Child.

It’s no wonder why this would trigger Link’s loving persona. After all of his abandonment, particularly from Navi and his own mother leaving him without explanation, he would likely spend a vast amount of time wondering if they did the right thing, and if they were happier for it.

Not to mention, Link is likely very unsure of if what he’s doing is officially “the right thing.” But like everyone else, all he can do is trust himself, make a choice, and keep on swimming, which is exactly what he does in this section of the Moon’s playground, before facing the final question.

“Your true face…What kind of…face is it? I wonder…The face under the mask… Is that…your true face?”

What a question to be asked by the Twinmold Moon Child, representing the Stone Tower Temple and Link’s core self.

The Twinmold Moon Child.

Who is Link, really? Is he a hero, is he a child, is he a god, is he someone who loves deeply? Is he a mixture of all, or none?

Recall that in my explanation of ego states, I discussed that having them in conflict with the self results in a complete lack of a sense of self. It can be confusing and frightening to wonder if you are existing as your true self, or merely putting on a facade to others.

However, his sense of self, as the healer that he is, is strong by the end of his journey. As he’s readying for his final fight with Majora, Link is equipped with all of his ego states waiting in the wings to help him, but he is not depending on them taking him over.

Dawn of a New Day

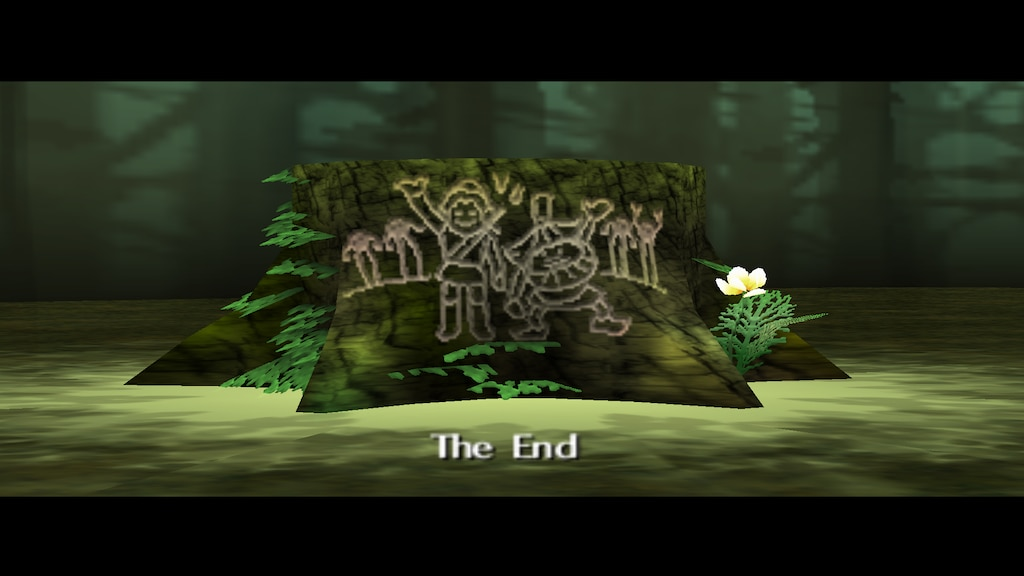

As we enter Dawn of a New Day, Link has done significantly more than saving Termina: Link has saved himself.

He fell to the truest depths. He lost his purpose as the Hero of Time, lost countless friends, lost his human form, lost his powers, and even lost his beloved horse. And while, yes, he does gain some of these precious items back, he gains something even more valuable.

A sense of understanding.

It is through Link’s travels, through his own journey of healing, that he is able to grow. He is able to recognize his masks, wear them, control them, and know when to step away. He has his sense of self restored, beyond some idealized perception of himself, beyond the ever-present doubts, fears, and questions.

He’s no longer aimless, lost, with no sense of self. He’s come to terms with his losses, he’s come to terms with his strengths, and it’s with this recognition of all aspects of his ego that he is able to part ways with Tatl to go on his own path, confident and whole. He is able to pursue the search for Navi once again, allowing it to drive him, but not consume him.

The understanding Link gains on his journey through Termina is not exclusive to himself, however.

The Giants advising Link to forgive his friend.

As a kid, I remember being very let down by the ending of the game. Skull Kid was forgiven, by the Four Giants, Tatl and Tael, and by Link. I couldn’t fathom this—he had caused so much pain!

But after the journey I had been through as an adult with my own ego states, I came to better understand the Skull Kid, and as such found a beauty in everyone forgiving him, particularly Link.

Link, after all, would fully understand Skull Kid by this point. Skull Kid took on Majora’s Mask as his own ego state: a sense of rage and cruelty formed by his feelings of abandonment. But where Link sought to work with his ego states and normalize them, the Skull Kid acted as an example of what would occur if the ego state remained in conflict and overtook the core self.

Link came to understand that the Skull Kid was simply in need of the same growth that Link himself had undergone. In forgiving him, he gave the Skull Kid the chance to forgive himself, and to undertake his own journey.

Skull Kid asking Link to be his friend.

After two decades of adoring this game, I have found an even deeper well of admiration for it. While I have long admired the writing of the story, the dialogue of the characters, and the aesthetics of the game, I had never fully grasped the complexity of Link’s psychological and emotional journey throughout his adventures.

Through my new lens of this game, I deeply resonated with the themes. My childhood avatar undergoing not the Hero’s Journey, but rather a personal one that so deeply mirrors the themes of my own. In its own graphical, mechanical, and artistic way, Majora’s Mask took me on a reflective therapeutic journey in a way that only a video game could. And as Link rode off into the dawn, I noticed that I, and all parts of myself, felt a deep sense of comfort and belonging.

Healing isn’t linear, and neither is Majora’s Mask. Yet the value of going through the cyclical process of healing is shown beautifully throughout the events in Majora’s Mask. If Link can go through such a deep and personal journey, then what is to stop the player from doing the same?

- Debates on this can be found on forums such as Zelda Universe, Zelda Dungeon, and GameFAQs. ↑

- Notice that this perfectionist ego state contrasts directly with the hero ego state. While the perfectionist state is internal expectations and wishing himself to be flawless, his hero ego state derives from external expectations and wishing others to be safe and/or happy. ↑

- What about the fact that one of these statues seems to represent Link’s core, his Hylian form, rather than an ego state? I postulate that this is a representation of Link’s newfound ability to identify his core self amidst his other ego states. This differentiation is a difficult task in early stages of ego state therapy, as when your ego states are in conflict, you can lose a sense of your core self. Link’s ability in the Stone Tower Temple to step back and see his own core is further evidence of his growth throughout the events of Majora’s Mask. ↑

- One might wonder how the psychological function of these lesser masks relates to Link’s ego states, considering that Link has to give away each of these masks in order to obtain the Fierce Deity’s Mask, which acts as his perfectionist ego state. Given our earlier analysis of the perfectionist ego state, I think the best explanation is that his handing off these lesser masks is a symbol of him needing to relinquish his emotions in order to call upon his perfectionist ego. This comes from personal experience with a similar ego state, and how difficult it can be to feel any minor emotion within said state. ↑