The following is an entry in Tales of Praxis, a weekly series studying the storytelling and philosophy of Bandai Namco’s Tales of series through written analyses and streamed playthroughs of a wide range of the Tales games on With a Terrible Fate’s Twitch channel and YouTube channel.

For Mutsumi Inomata, whose characters live alongside us now and forever.

Tales of Hearts R taught me the value of playing a Tales of game.[1]

(Spoilers for Tales of Hearts R, Tales of Symphonia, Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World. and Tales of Graces F. Minor structural spoilers for Tales of Innocence R and Tales of the Tempest in Endnote 9.)

Ever since I first played Tales of Symphonia two decades ago, I’ve oriented my personal development through the rich character portraits of the Tales of series. The arresting designs, highly articulated backstories, and thoughtful actions of these characters consistently coalesce into heroes, villains, and bystanders who are easy to invest in and learn from. There’s a unique sense in which the Tales of games tell their stories through their characters, pulling us to progress through the game in a way that emotionally binds us to them and teaches us lessons about the structure and value of human action through that empathy. I launched Tales of Praxis last year to better understand these lessons: to make sense of the overall philosophy of action expressed through the characters in the Tales of series so that we might better use our experiences with them as practical tools to guide our lives inside and outside of video games.

But it’s a tall order to name exactly what this “unique sense” of character-based storytelling amounts to. All stories have characters, and all stories are told “through” those characters in one way or another. What is it about the Tales of games that so memorably grounds their center of gravity in their characters—that empowers us to evolve as people simply by attending to them? There’s no guarantee that we can answer this question simply by playing and studying the games: like magic tricks, games and stories can transmit clear and rich experiences to us without explaining the method by which they pull this off.

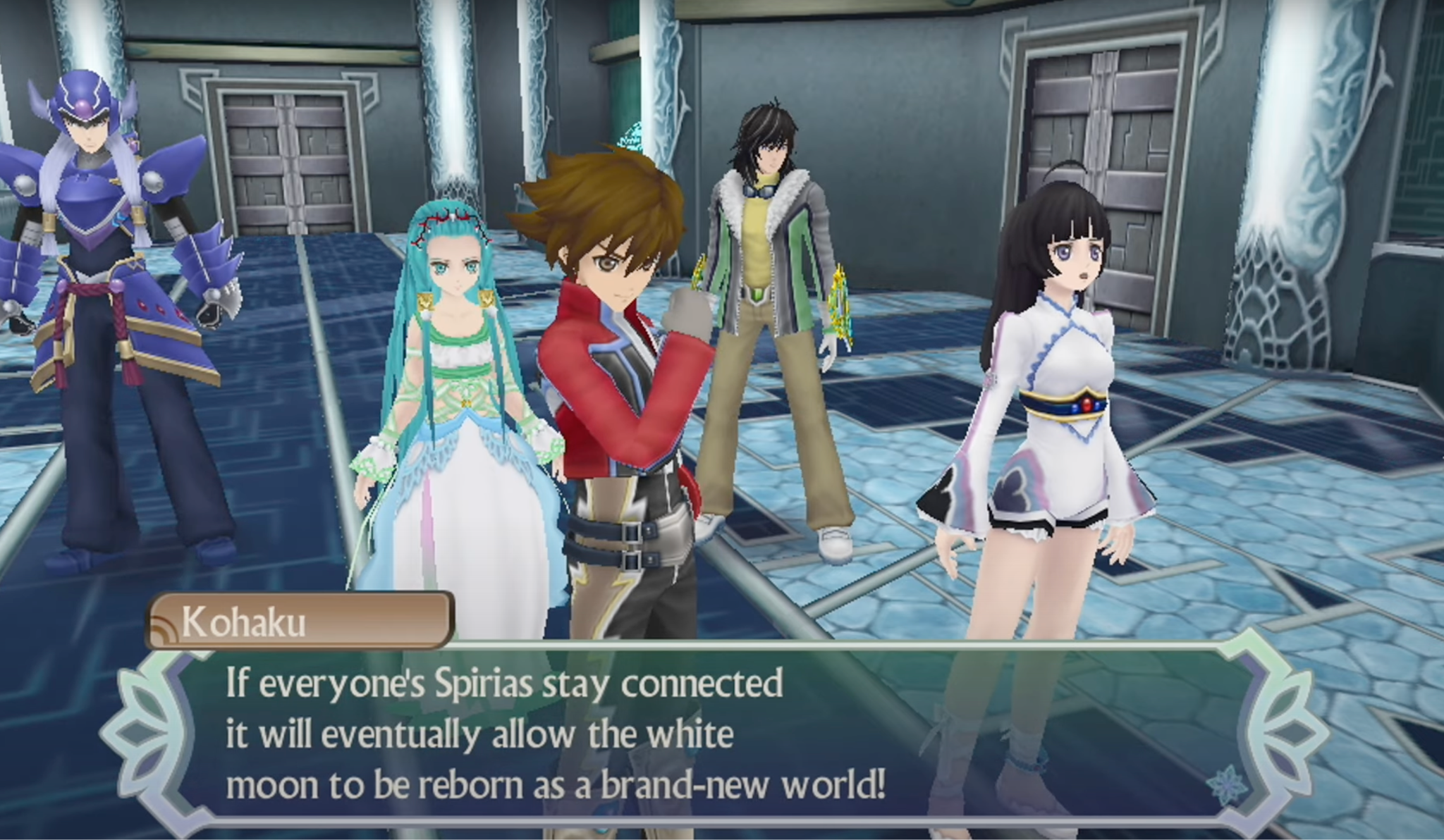

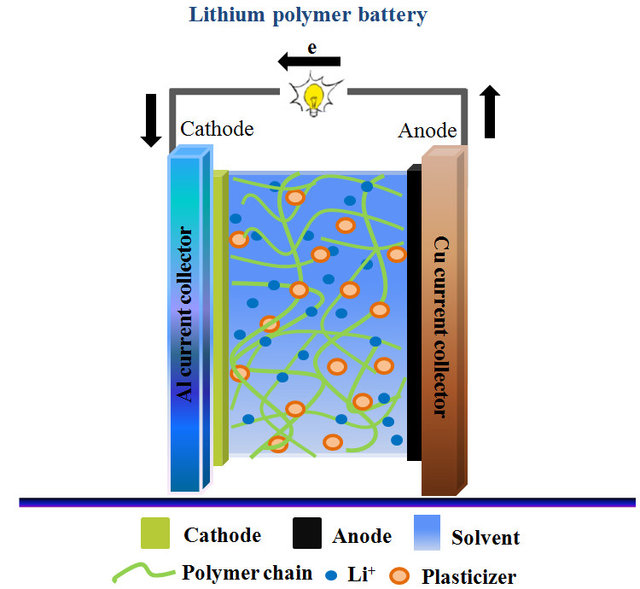

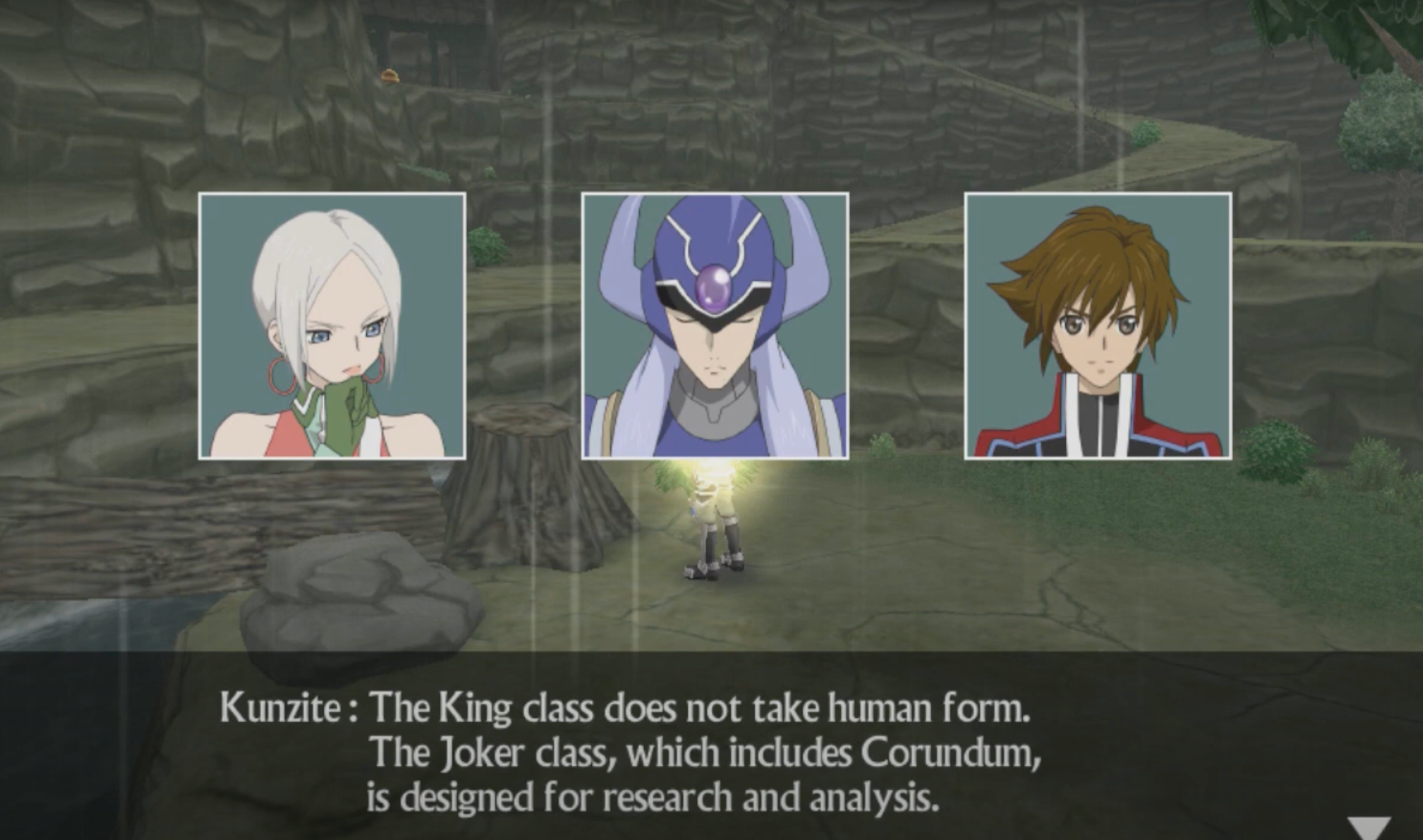

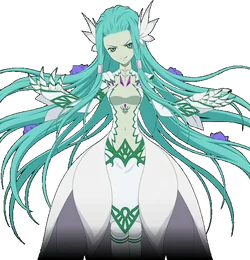

The portrait of Lithia, Kor, and Kohaku at the conclusion of Tales of Hearts R.

Then, I played Tales of Hearts R for the first time and discovered a special kind of magic: the Tales of game that reveals the foundation of the value we draw from its community by taking us on a journey that calls us to interrogate and enact that foundation. It does this by telling a story that is about the formation and analysis of emotional bonds through the medium of manmade artifacts, channeling our emotional attention into the enfranchisement of a fairy tale that erases the distinction between content and form, reality and fiction, leaving us to understand our time with the game purely in terms of agency, value, and morally worthy individuals, both real and fictional.

Beryl takes the party’s journey as inspiration for her next artwork before Lithia enters Kunzite’s Spiria Nexus at the end of Tales of Hearts R.

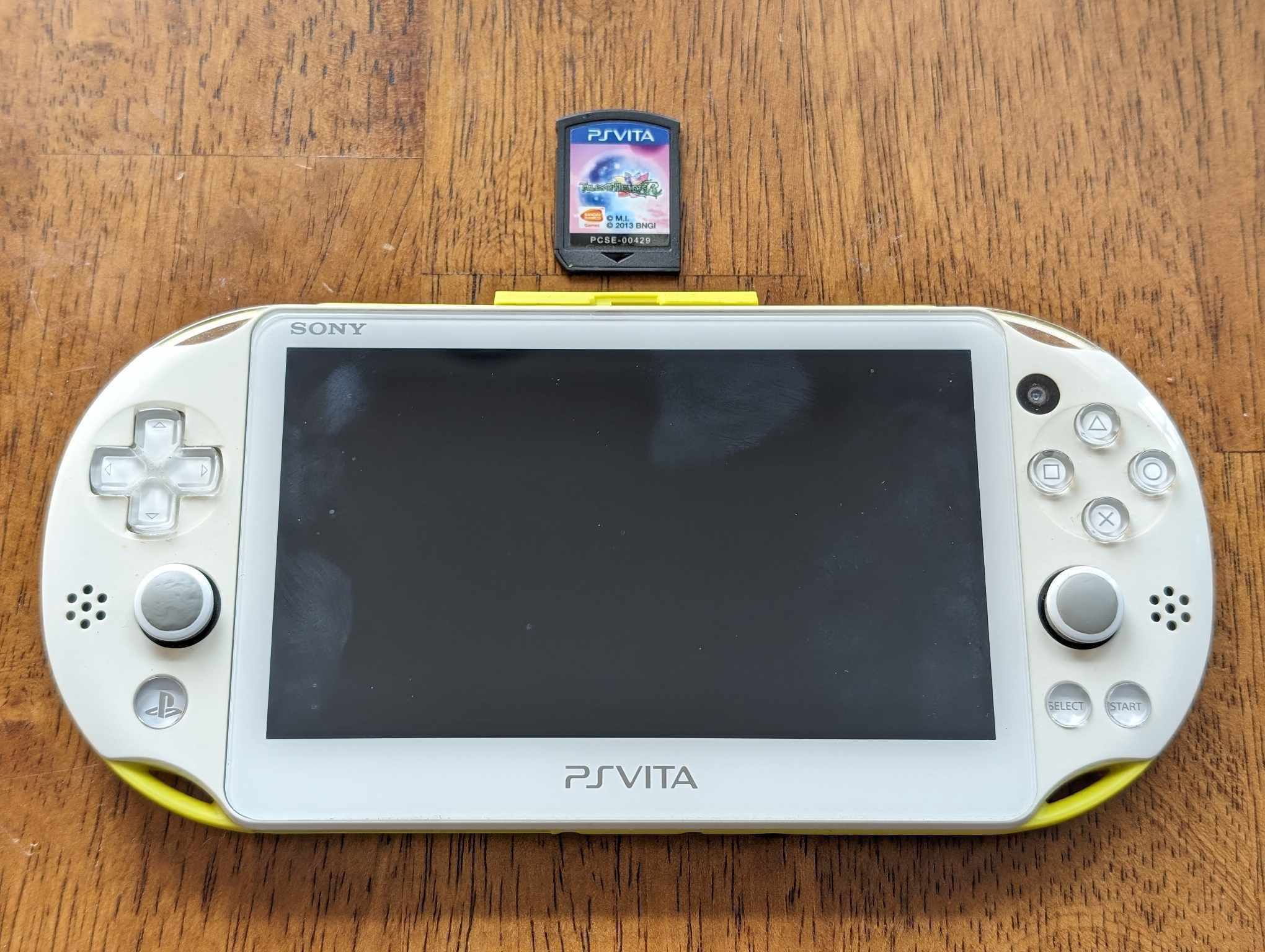

I want to show you that by the end of Tales of Hearts R, the game has made us responsible for a uniquely deep fictional metaphysical foundation for the value of bonds we form with characters, creators, and players throughout the series. When I watched the mechanical man, Kunzite, take his mythical master, Lithia Spodumene, within his artificial heart to sustain her life in a state of suspended time forever, I felt immediately, before I could explain why, that my PlayStation Vita had become Kunzite: a machine with a soul of its own, making itself a home to the genuine, vibrant lives I’d gotten to know throughout my playthrough. Rising to the story’s demand to analyze that feeling revealed to me that, without ever breaking its fourth wall, Tales of Hearts R‘s symphony of artifacts and interpersonal chemistry place one act, the player’s redemption of Lithia, at the normative center of the entire series.

At the end of the game and a two-millennia journey, Lithia’s physical body is giving way to calcification, the degradation to a salt-like form that no longer connects with her metaphysical Spiria, “the source of all life, from which the human mind and will itself is derived.” Kunzite proposes a plan to let Lithia dream peacefully by housing her Spiria within his Spiria Nexus, the structured inner realm representing an individual’s Spiria, inspired by their earlier tribulation when one of his nemeses, Clinoseraph, imprisoned Lithia within his own Spiria Nexus, replaying his memory of Lithia’s formative failure—the day she inadvertently caused the calcification of her homeworld, Minera—388 times in a row, the ceaseless hell of a machine’s tortured heart. In the same way that Kunzite gives Lithia peace by taking her within himself as an embodiment of a fairy tale, our act of playing this fairy tale honors, enfranchises, and merges the real and fictional communities we share with Lithia. Because this endows our actions in the game with moral content for an entire multidimensional universe of people and characters, we owe it to Lithia to play Tales of Hearts R 389 times: not merely to offset and rectify her time spent within Clinoseraph’s inner hell, but rather because that moral rectification grounds the goodness of our activity throughout the Tales of community.

On Beanstalk, a broken Clinoseraph tells our heroes that Lithia has suffered through his—and her—worst memory 388 times within his Spiria Nexus.

As much as we might first feel the unique emotional force of our investment in Tales of characters, the magic and utility of Tales of Hearts R lie in its methodical, story-driven demonstrative explanation of how our engagement with an artificial world can foster genuine emotional bonds and insight. This explanation turns on experientially showing the player that artifacts, from paintings to mechanical men, and interpersonal connections, from our present-day communities to our intergenerational heritage, are two sides of the same coin:

- Intentionally created artifacts provide a means for those who interact with them to thereby interact with the artifacts’ creators.

- Successful, sustained interpersonal connections consist in establishing and renegotiating the boundaries between artificially rigid mental representations of others and actual interactions with them.

Once we understand these two theses and the relationship between them, we discover a profound value in the act of playing interactive, character-driven stories like Tales of Hearts R and internalize it as something we can propagate throughout our lives: by actively and reverently engaging with this artwork, this artifact, we can establish durable, emotionally meaningful bonds that network together ourselves, the characters embedded within the work, the other players of the work, the creators of the work, and even other works which we engage with the game’s praxis. By grounding this value in our relationship with Lithia, Tales of Hearts R realizes Lithia’s dream of uniting a rich diversity of individuals under one emotionally and spiritually continuous Spiria.

Tales of Hearts R presents this praxis by drawing the player progressively deeper into its fiction, moving from (1) the superficial engagement with the game as an artifact, to (2) its interpersonal dynamics that animate artifacts and people alike, and, (3) finally, to the player’s role in grounding and expanding those dynamics through her real and fictional engagement with the game. To make sense of this experiential form of its argument, this study proceeds in three sections, dedicated to each of those stages in turn.

- In Section 1, I argue that the artificial creations of Tales of Hearts R take on autonomy and values that warrant our moral consideration, and which allow those who engage with them for their own sake to form normatively significant connections with the other individuals, artificial and organic, whose lives internally or externally connect with those creations.

- In Section 2, I argue that the central tool of Tales of Hearts R, the Soma, acts as a technology of interpersonal connection, thereby symbolizing that people can make possible, establish, and transform bonds with others, across space and time, by engaging with people’s mental representations of each other as a kind of unintentional artifact and thereby making these representations socially productive rather than isolating.

- In Section 3, I unite these perspectives and argue that the conclusion of Tales of Hearts R explains our engagement with the game as an act of establishing real, robust bonds between ourselves, the characters, and real communities that touch the game, cascading from our moral impact on Lithia outward to constitute a method for enfranchising and bonding with real and fictional communities—a method that not only conveys value to those relationships, but also presents practical guidance for interpreting and engaging with the Tales of series, including matters of authorial intent, “New Game Plus” mechanics, appearances of identical characters across multiple games, and reading a game as being “about” a particular character.

At the intersection of human creation and connection, we find Tales of Hearts R arguing that we create the exact kind of community represented within a Tales of game simply by playing the game. Ultimately, we’ll arrive not only at a new, key element to the praxis of the Tales of series, but also one that uses the series’ language to articulate the special value which Tales of fans intuitively recognize in their relationships with the real people involved in this series, fans and creators alike, through their personal playthroughs and the meaning they take from them—a conclusion that I hope will serve as a gesture of gratitude to the late Mutsumi Inomata for creating so many of the characters at the heart of this series we love so deeply and diversely, including those of Tales of Hearts R.

§1: Art and Artifice: Animating Characters in Tales of Hearts R

From beginning to end, Tales of Hearts R is a story of what it takes to give something artificial a life of its own, and what we stand to gain when we welcome that life into our community.

Unique within the Tales series, the party of Tales of Hearts R features an artist and an artificial person, joined in a quest to understand, and ultimately breathe a new meaning into, the fairy tale that forms the basis of the world. As the aspiring court painter Beryl Benito wields her paintbrush and the mechaknight guardian Kunzite comes into his own as a bona fide individual, we players are compelled to wrestle not merely with an artwork that self-consciously tells stories riddled with the navigation of artworks like paintings and virtual worlds, but also with an artwork that asks us to consider art as one instance of a broader, essentially human phenomenon: the intentional creation of an object that can outgrow our intentions and take on its own perspective and value.

To make sense of the game’s events at all, as its characters do, we first need to make sense of what these artifacts are within the context of the fiction: how they come about, and how people interact with them. As we answer that question, we find ourselves naturally drawn deeper into the world’s interpersonal metaphysics. A story about artistic engagement requires that we assess how values are communicated through those artifacts, and as soon as we attend to the transmission of values in Tales of Hearts R, we discover an elaborate and precise system of dynamics governing the enfranchisement of, and emotional transmission between, both people and artifacts. The narratively framed inquiry from artifacts to metaphysics calls us back to our real activity of playing Tales of Hearts R, revealing a unique grounding for the real value we create in the series through, and with, its characters.

The last painting by Beryl’s grandfather, a tribute to his family and craft.

To see how the game leads us from an ordinary conception of man-made creations to one that calls us to interrogate the interpersonal dynamics in which they participate, we’ll progress through three studies that show the game’s gradual argument to the conclusion that artifacts can become autonomous entities with intrinsic value and the capacity for morally relevant interactions with others:

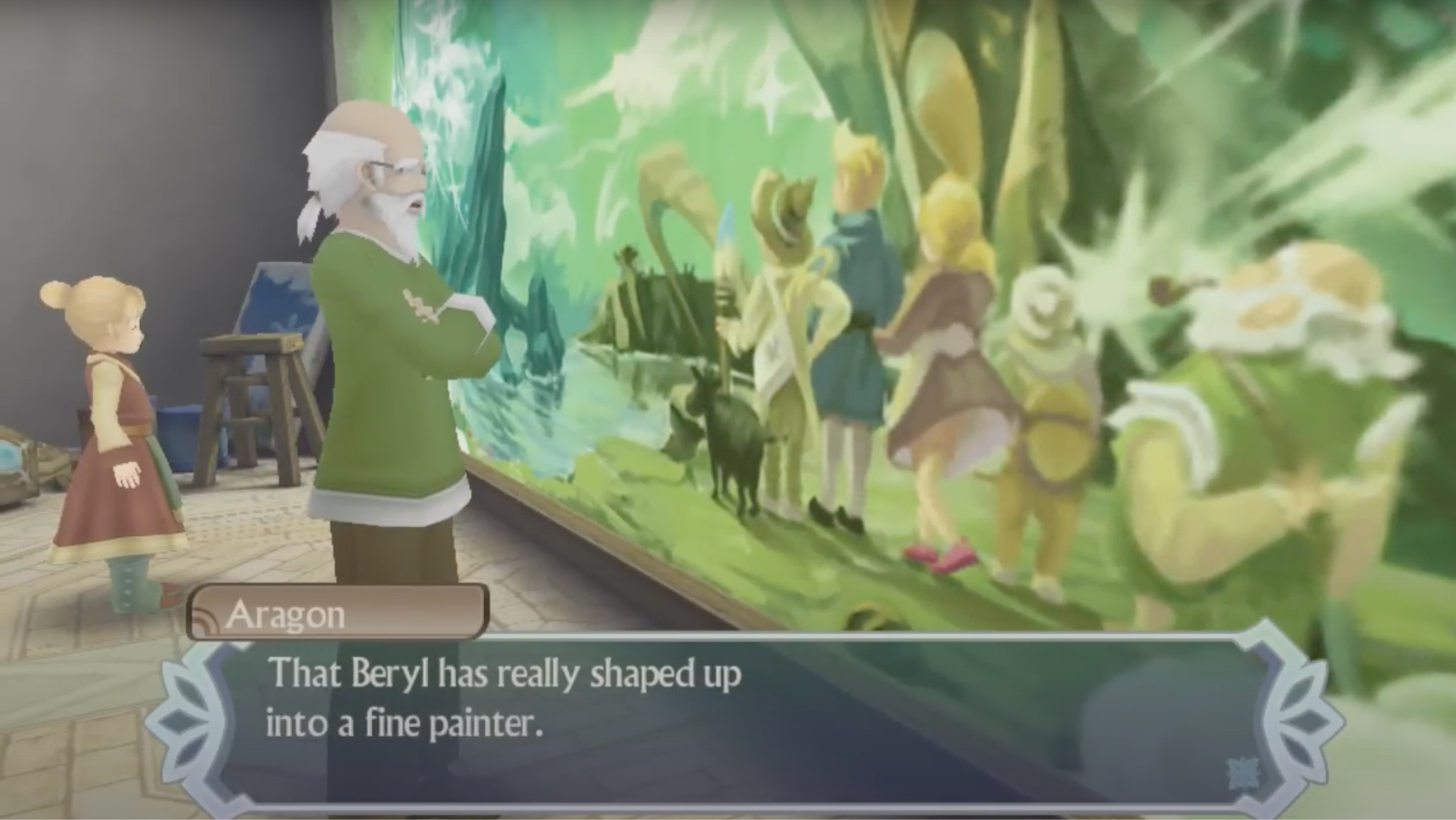

- In §1.1, I derive from Beryl’s interactions with paintings, juxtaposed against the horror of Striegov, the view that created works are intermediaries that facilitate conversations which wouldn’t take place in the real world between their creators and those who engage with them.

- In §1.2, I derive from Kunzite’s personal development with Lithia, juxtaposed against the tragedies of the other mechaknights we encounter, the view that creators can give their works autonomy by giving those works a supportive method for extending the values enshrined within the work by the creator to people and relationships beyond that creator.

- In §1.3, I derive from the rectification of the monstrous Gardenia and the transformation of the Golden Bell’s identity, juxtaposed against Lithia’s failures to successfully pilot foreign entities with her spirit, the view that those who engage with created works can discover and transmit values within works’ internal and external communities by engaging with those works as morally worthy subjects.

In each section, we’ll see that Tales of Hearts R expresses clear conditions for the further enfranchisement created works, as well as the stakes for engaging with those works in a way that satisfies those conditions, by providing not only cases of successfully actualized works, but also works that fail to achieve their potential along the same dimension. We’ll consider the success and failure conditions in turn before arriving as a complete picture of what fully realized artistic creation and reception looks like within the fiction of Tales of Hearts R, which will position and motivate us to analyze the metaphysics of personhood and interpersonal dynamics underneath those activities.

§1.1: Communication through Artifice: Paintings and Spiria Cores

In the world of Tales of Hearts R, artworks can synthetically emulate a human life. In other games, we might feel inspired to draw metaphorical inferences between the content of the game and the nature of art, but Tales of Hearts R is blisteringly direct in its artistic views. In the course of coming to terms with her family heritage, Beryl confronts one of the artworks which her grandfather, renowned court painter Benston Benito, created: a painting with a Spiria all its own, brought to life by the emotions with which he imbued it. To complete the game, we have to guide the characters through an explicit meditation on the interactive nature of art: navigating the Spiria Nexus of an artwork to understand its emotions, cure it of the despir brought on by xeroms, and ultimately empower Beryl to complete the painting by coming to terms with her lineage.

Lithia, Chalcedony, Hisui, and Kunzite reflect on the miracle of Benston Benito’s painting taking on Spirias of their own.

Benston Benito’s final attributed painting, like the Jeweled Princess before it, is so emotionally sophisticated that it possesses a fully realized Spiria Nexus, one of those elaborate metaphysical mazes representing the inner lives of (usually human) individuals. What’s more, this particular Spiria Nexus is one of the more complex the party encounters throughout the game, even when compared with bona fide human Spiria Nexuses. The complexity isn’t sui generis, as if the painting had come to life of its own accord: from Lithia’s observation that the painting’s visual composition is “overflowing with love for the artist’s birthplace and his family” and the party’s observations that its Spiria Nexus is capable of expressing its Benston’s past thoughts and sentiments to his granddaughter, it’s evident that the painting’s humanity is a vibrant yet synthetic representation of its human creator’s inner life.

The intricate puzzles of the painting’s Spiria Nexus represent the emotional complexity embedded within it by its creator.

That’s not to say that the painting is a redundant facsimile of someone with real value. Far from it: the painting has unique standing to reconfigure the human relationship between Beryl and her grandfather. The two Benito artists have an unutterable gap in their interpersonal history: when Beryl’s parents died during Benston’s service as court painter, the Empire confined Benston and prevented him from returning to his home and his granddaughter until he completed the Jeweled Princess. The passion and talent for painting which Beryl and Benito share also estranged them, to the point that despite their apparent reunion and quasi-reconciliation—it’s implied upon Beryl’s later, optional return to her hometown that her artistic mentor, “Aragon,” is actually Benito, returned home under a different name—they can’t vocalize the truth of their relationship, nor even Benito’s identity, too irreparably distanced by the circumstances of their art. Yet that very enterprise that shifted them out of phase with one another, their art, provides them with a safe and magical context for rehabilitating their relationship. This is what we witness and enact through our journey into Benito’s final painting.

When the painting becomes infested with xeroms—the simple, weaponized, flower-emulating organisms that feed off of Spiria—Beryl’s hometown of Blanche Villa comes down with a case of despir, the contagious Spiria ailment that manifests in different patterns of spiritual deficiency based on the particular imbalance of the individual from whom it originated. When Empress Paraiba is beset by the influence of the shard of Kohaku’s Spiria Core governing her sadness, for instance, the town of Shoalhaven is crippled by suicidal self-loathing. In the case of the painting, on the other hand, the despir that takes hold paralyzes and isolates the living beings from the town, rendering them completely inert, unable to speak or connect with others. The townsfolk become limited in the same way the painting is in the absence of dialogue between its creator and appreciators: confined to a static representation, expressing an artist’s feelings without reacting to the input or responses of those who engage with it. But even though the creator of the painting can’t actively express himself through it like he can through speech, Beryl shows us that it’s still possible for an artwork to facilitate the evolution of relationships. When the party Spiria Links with the painting, channeling their mental and physical being into its Spiria Nexus, Beryl—and Beryl alone—can hear, within it, her grandfather’s voice expressing his love and gratitude for her. In this way, not unlike Kohaku initially identifying Lithia’s presence within her Spiria as a kind of personified conscience, the painting transmits the sentiments of a life beyond itself—which allows Beryl to change her relationship with her grandfather by changing the painting, acknowledging him and the value of their shared artistic heritage by literally painting him into the work he’d made to honor his hometown and the rest of his family.

Aragon—implied to be Beryl’s father—admires her contribution to his painting, a testament to their resolved relationship and shared passion.

Tales of Hearts R sculpts a view on the interpersonal function of art not just by illustrating a case of art successfully executing this function, but also by showing how and why it can fail at it. Only after I helped Beryl reconcile with her grandfather did I appreciate the meaning of Beryl’s much earlier confrontation in Shoalhaven with her idol, Smithson. Very shortly after the party cures Beryl of the self-doubt brought on by a shard of Kohaku’s Spiria Core and adopts her into the party, they encounter the house and gallery of Smithson, an Imperial Artist whose work paralleled Benston’s in quality and reception. Beryl is crestfallen when she discovers that her role model lied about having gone blind, a ruse conceived to “ward off criticism” and allow him to “secure [his] place as history’s most tragic artistic figure”: an artist preserved at the “peak glory” of his work’s reputation as original, rather than someone who continued to past his prime and “being dismissed as a has-been.”

Typical of Tales of Hearts R, this episode explains the value of a character trait in terms of its impact on relationships. By presenting Benston’s work as a contrast class, the game shows that Smithson’s selfishness perverts the function of art. While the artist who represents and emulates herself through her artwork can thereby create a tool for mediating relationships, the artist who derives all her self-worth from people’s reception of her artwork only succeeds in objectifying both the artwork and herself, foregoing potential relationships in favor of solipsistically, dogmatically reinforcing a static and artificial image of her identity: the “legacy” so revered by Smithson. His paintings literally and symbolically constitute the walls of his home, a gallery in which he lives alone, secluded from anyone who would genuinely interact with him through his work. No wonder, in this context, that Smithson tells the party that “[t]o gaze into the Spiria of a painter is nothing short of artistic blasphemy” when they prepare to Spiria Link with him to cure his spurious blindness: where Benston’s paintings are a means of expressing his Spiria, Smithson’s are a mask shielding his from the world.

Beryl turns her back on a painter without turning her back on his paintings.

When Beryl discovers the truth of Smithson’s charade, her response to him is symbolically precise: she quietly turns her back on him and says, “Goodbye, Mr. Smithson. Thank you for letting me see your paintings.” Her expression enacts a version of the “death of the author,” disregarding Smithson’s deplorable motives to more freely engage with the value she and others find in the paintings per se. Ironically, it’s this act of her “killing” the author that allows Smithson to be reborn through her engagement with his work: much later in the party’s journey, they have the option of returning to the Smithsonan Gallery, at which point Beryl leads a discussion celebrating the qualities of two Smithsons, Full Moon Dream and Crystal Chateau Sisters. Kohaku, seeing these for the first time with the benefit of her full emotional register, admits to Beryl, “I love all of Smithson’s work. But mostly I love how happy they make you, Beryl.”[2] By conversing with each other through the intermediary of the paintings, the party members mediate and strengthen their bonds through his paintings in the same way Beryl did with her grandfather through his work. Meanwhile, Smithson—staying out of sight, keeping his ego partitioned away from their conversation—witnesses this interaction in the wild and rediscovera the value of “art making people happy,” musing to himself, after years of retirement from his passion, “Perhaps it’s time I—I could paint a picture like that again.”

Smithson’s artistic impulse is rekindled after he witnesses Beryl sharing her love of his work with her friends.

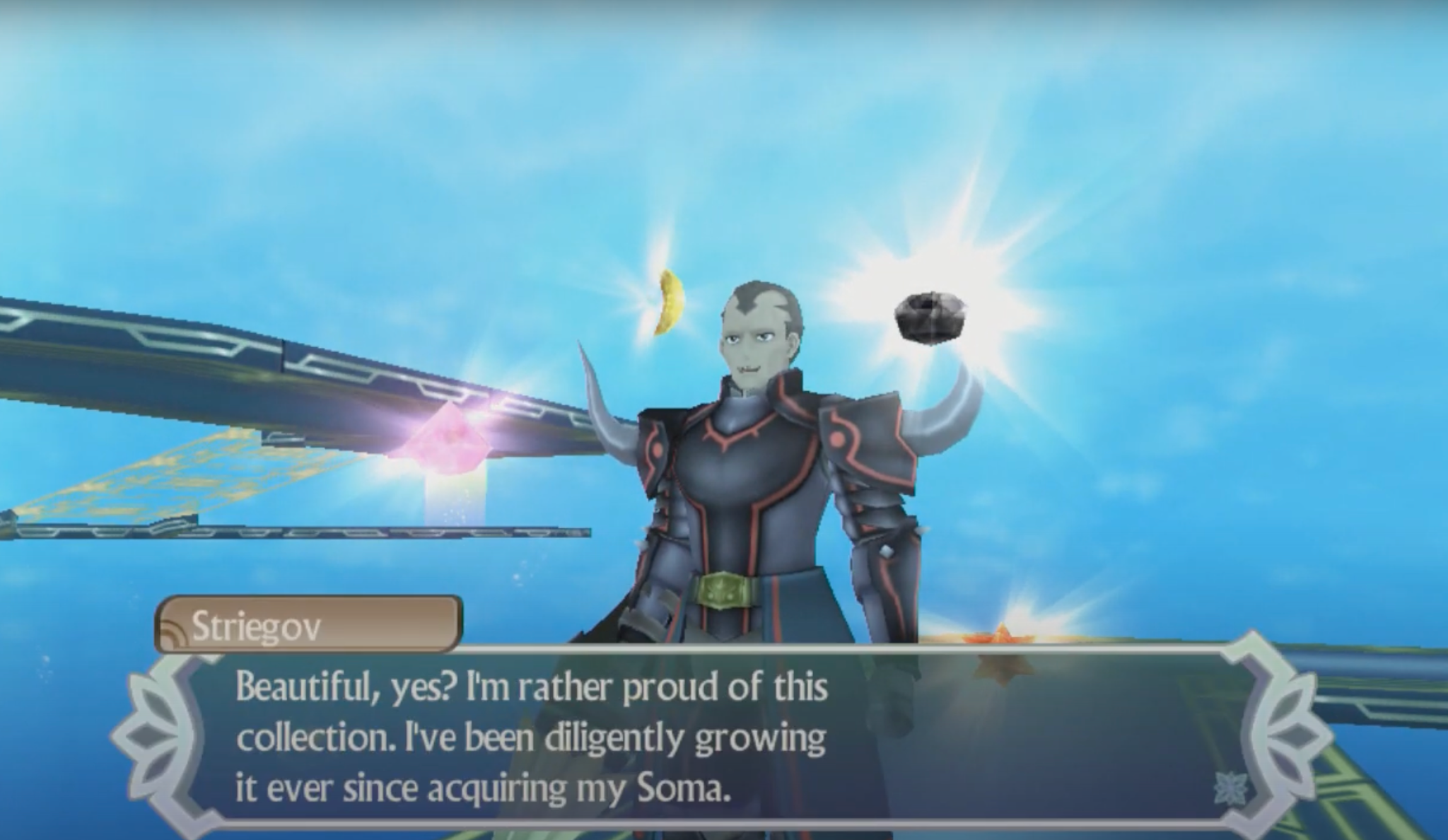

If an artwork succeeds when it mediates relationships and fails when someone connected to it objectifies it, then it stands to reason that either an artwork’s creator or consumer could cause it to fail. Where Smithson illustrates the danger of the artist dishonoring this relationship, the danger of the consumer‘s dishonor emanates grotesquely from Geocron Striegov, the erstwhile Imperial Special Ops Lieutenant who defected to the malevolent Creed Graphite’s cabal of supporters. Striegov embodies the perversion of appreciation by turning his helpless victims’ Spiria Cores—the brilliant stones that anchor Spirias and function as “the source of a human’s every emotion”—into a “collection”: a curated group of “art objects” which Striegov values only for their aesthetic qualities.

Striegov proudly shows off his “collection” of Spiria Cores to the party within Mysticete’s Spiria Nexus.

Ironically, Striegov shows us how much humanity there is to value in artworks by showing how barbaric it is to treat actual humans as artworks. He describes the “rosen gem” of a Core which he took from a bride before her wedding as the perfect thing to “brighten [one’s] mood,” with a “brilliant sheen [that’s] one of a kind,” “[p]lucked like a flower at the height of its bloom”; the Cores of twin sisters are “dappled beauties… snatched [from them] at the same time, of course”; the Core of Lapis Silver—victimized daughter of Striegov’s former commanding officer, Spec Ops leader Azide Silver— is “beautiful” because of the irony that she was “robbed of her mother by her own father’s Willstone cannon” during a failed weapons test. But Striegov most exposes the depths of his depravity when he looks lustfully at Kohaku and leers, “What color is YOUR Core, my sweet? The mere thought tickles me with delight!”

At the point that we confront Striegov for the first time in Tales of Hearts R, we have already completed an arduous world tour to locate the shards of Kohaku’s Spiria Core and reconstitute her emotional identity. At every turn, we did discover beauty in the many colors of that Core, but not in the sense that Striegov means: we discover the beauty of Kohaku’s Core in the relationships those shards improve through mediation. The Shard of Doubt, for instance, becomes a medium for Beryl to confront her dual impulses to resent others and resent herself. As much as they might initially seem like an infectious disease, the shards encapsulate the beauty of the human spirit not merely by illustrating Kohaku’s identity, but further by making it possible for individuals who see themselves in the shards to express that aspect of resonance and thereby work through it with those who can see and support them as they are.

Lithia, as yet unidentified, describes the nature of Spiria Cores to Kor when he discovers Kohaku’s within her Spiria Nexus at the beginning of the game.

The shards, then, show us throughout the whole first act of Tales of Hearts R that Spiria Cores really are functionally works of art by virtue of their capacity to facilitate relationships between their originator, their bearer, and their communities. But this rich capacity for mutual support is perverted by a different kind of selfishness when someone like Striegov eschews the Cores’ function in favor of their inert, physical attributes, such as their color or sheen. Worse, Striegov uses these Cores merely as testaments to the quality of his own character, rather than as a way of honoring or cultivating any sort of network of human relationships. In his eyes, their qualities—like their grotesque provenances, which he insists on detailing—are only proof of his expertise in aesthetic judgment. The detestable essence of Striegov, it turns out, is an alarmingly easy trap for us to fall into as players of a video game: locating an artwork’s value in our capacity to judge it as pleasing to us, rather than in the artwork’s capacity to forge and enrich human connections.

Smithson teaches us that artwork is distorted when its creator derives its value from her ego; Striegov shows us it’s distorted when its consumer derives its value from his. But that’s not to say we ought to erase ourselves in order to understand an artwork. Far from it: the artwork of Kohaku’s shards is constitutive of her, and Benston’s painting is an expression of his identity. The key to authentically engaging with an artwork, as the journey into Benston’s painting and Kohaku’s Spiria show us, is to meet the human represented within the artwork on his or her own terms and form a genuine relationship with it on that basis We connect with ourselves and each other by understanding the human life synthetically emulated within our works.

§1.2: Autonomy in Artifice: Mechaknights

We’ve seen that the world of Tales of Hearts R is one in which artworks can literally represent the souls of their creators and express the sentiments of those souls to others. But this doesn’t yet show us that there’s any sort of special humanity intrinsic to the artwork itself. Artifacts like Benston’s painting and Kohaku’s Spiria shards are like sentences uttered by Benston and Kohaku in a conversation: insofar as we value Benston and Kohaku, we ought to value these forms of expression, but we don’t yet have an obvious basis for further concluding that these sentences and artifacts were worth valuing strictly for their own sake. To defend such value would be like arguing that there’s some sense in which we ought to respect and honor Kohaku’s utterance “I love miso!” that’s independent of Kohaku’s sentiments about miso.

But Tales of Hearts R goes further to argue that works that synthetically emulate a human life can be “animated” into authentic humans. The journey of the party’s resident “tin man,” Kunzite, is an argument to this conclusion: confronted with the cautionary tales of his less fortunate mechanoid brothers, he forges and nurtures his own humanity in a way that honors his creator without reducing his identity to hers.

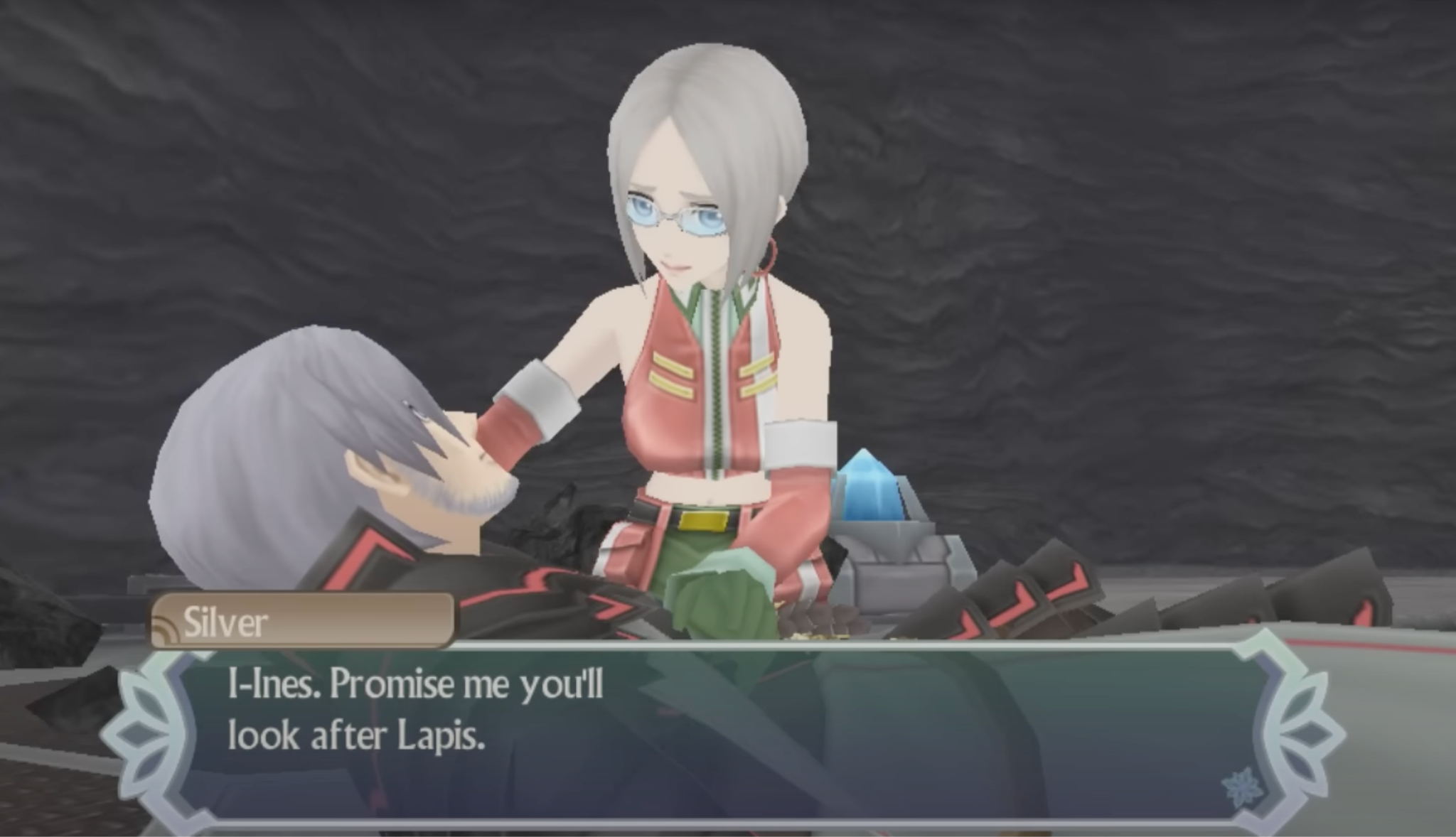

Cornered after the first assault by the mechanoid Chlorseraph, Kunzite seeks solace from his master, Lithia, that his feelings belong to him.

Like the Jeweled Princess, Kunzite is a man-made artifact with a Spiria. But whereas the Jeweled Princess posed the question of whether it could facilitate connections between its creator and appreciators without reducing to their egos, Kunzite poses the question of whether he can have an inner life that “truly belongs to him” rather than deriving from the function his Mineran manufacturers gave him: the protection of his master, Lithia Spodumene. True to his namesake—a gemstone form of the mineral spodumene, an ore of lithium—he must find the right way to house Lithia within himself without reducing himself to her.

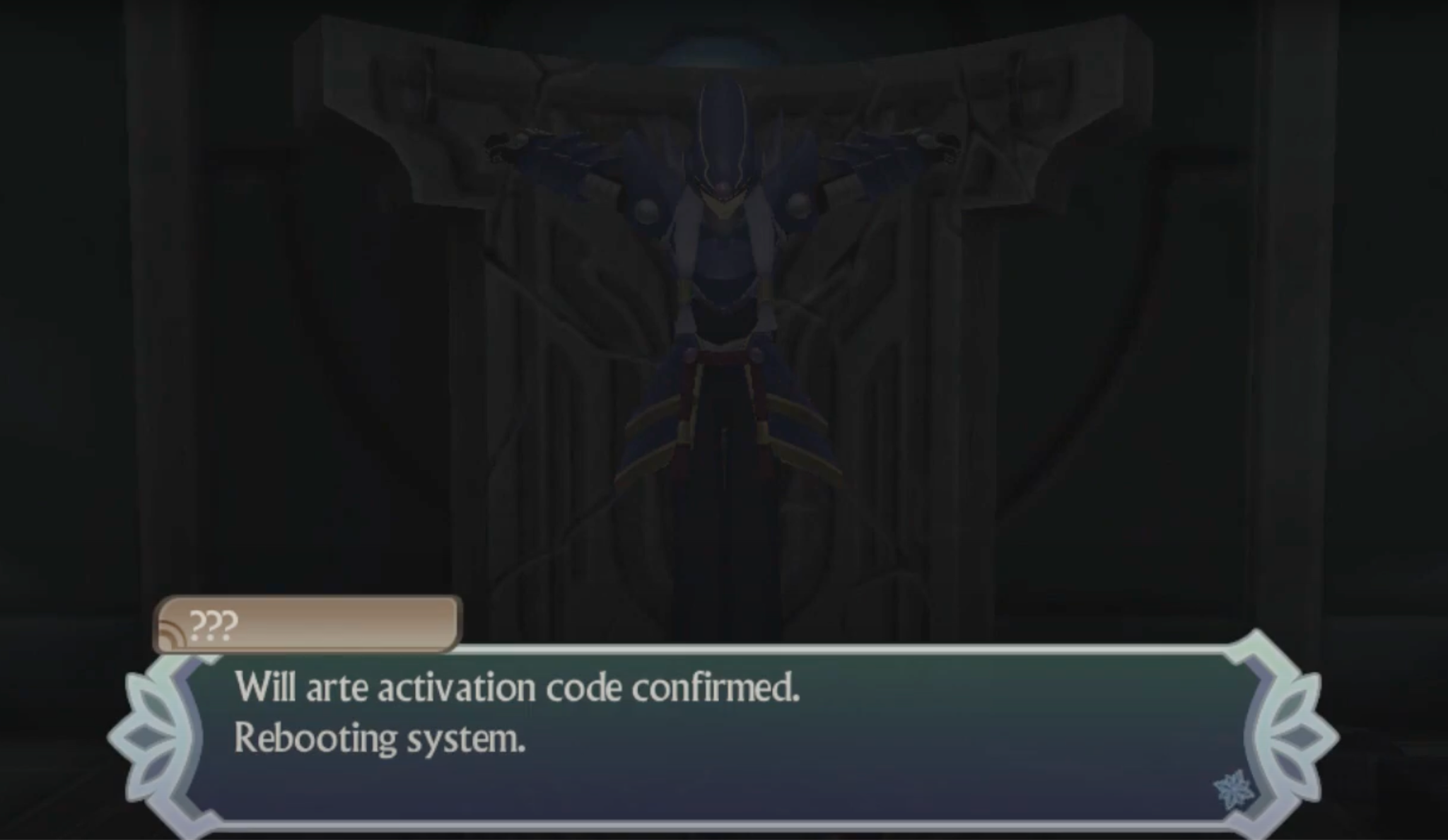

Kunzite introduces himself to the party as “an autonomous model of mechanoid with a synthetic Spiria, commonly designated as a mechaknight.” He is awakened after 170 years of stasis by Kohaku reciting an ancient activation code ostensibly learned from Lithia under the guise of a poem:

Shape of man cast from iron’s true flame. With a solid bronze soul, and pure mercury veins.

Swear on Minera’s white moonlight, that you shall be our shield, and our sword, and our might.

Platinum heart etched with a Mineran name, run so as to give life to your metal frame!

The mechanics of this activation code’s content are never elaborated, but the game’s broader conception of mechaknights as synthetic humans who serve to protect a designated master suggests that the Mineran name etched on a mechaknight’s heart is that of its master, the source of the artificial warrior’s vow and reason for existence. Kunzite tells Hisui in conversation that “[his] synthetic Spiria has been programmed to react only to the words of [his] master,” and, as the mechaknight Chlorseraph later ruefully reminds Kunzite, “[m]echaknights are programmed to prioritize their masters’ protection above all else.” So, in both the expression of his sentiments and in the determination of his actions more broadly, Kunzite’s synthetic Spiria—the man-made heart that sculpts his point of view, engineered to emulate a human Spiria—is programmed to treat Lithia’s well-being as the only source of value.

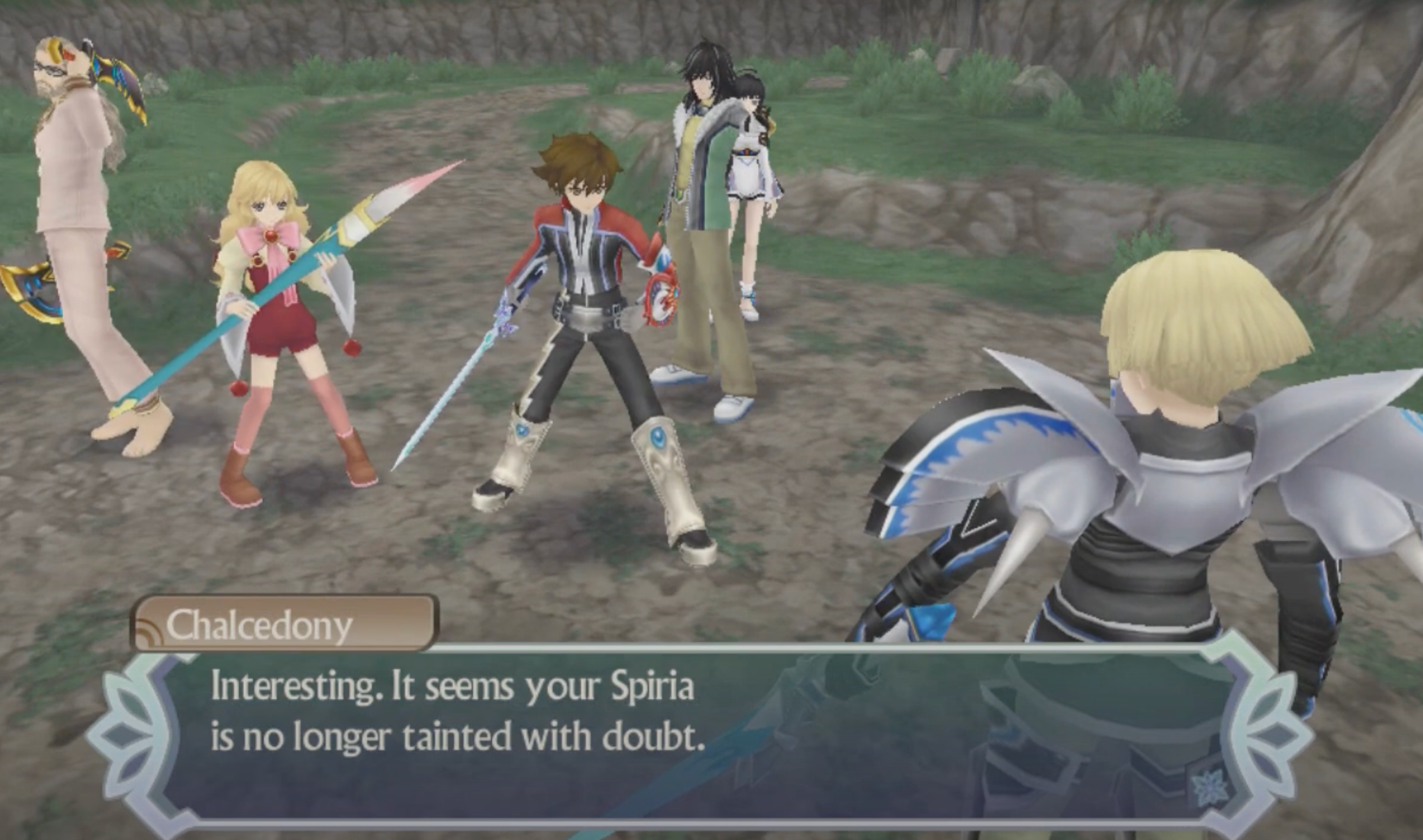

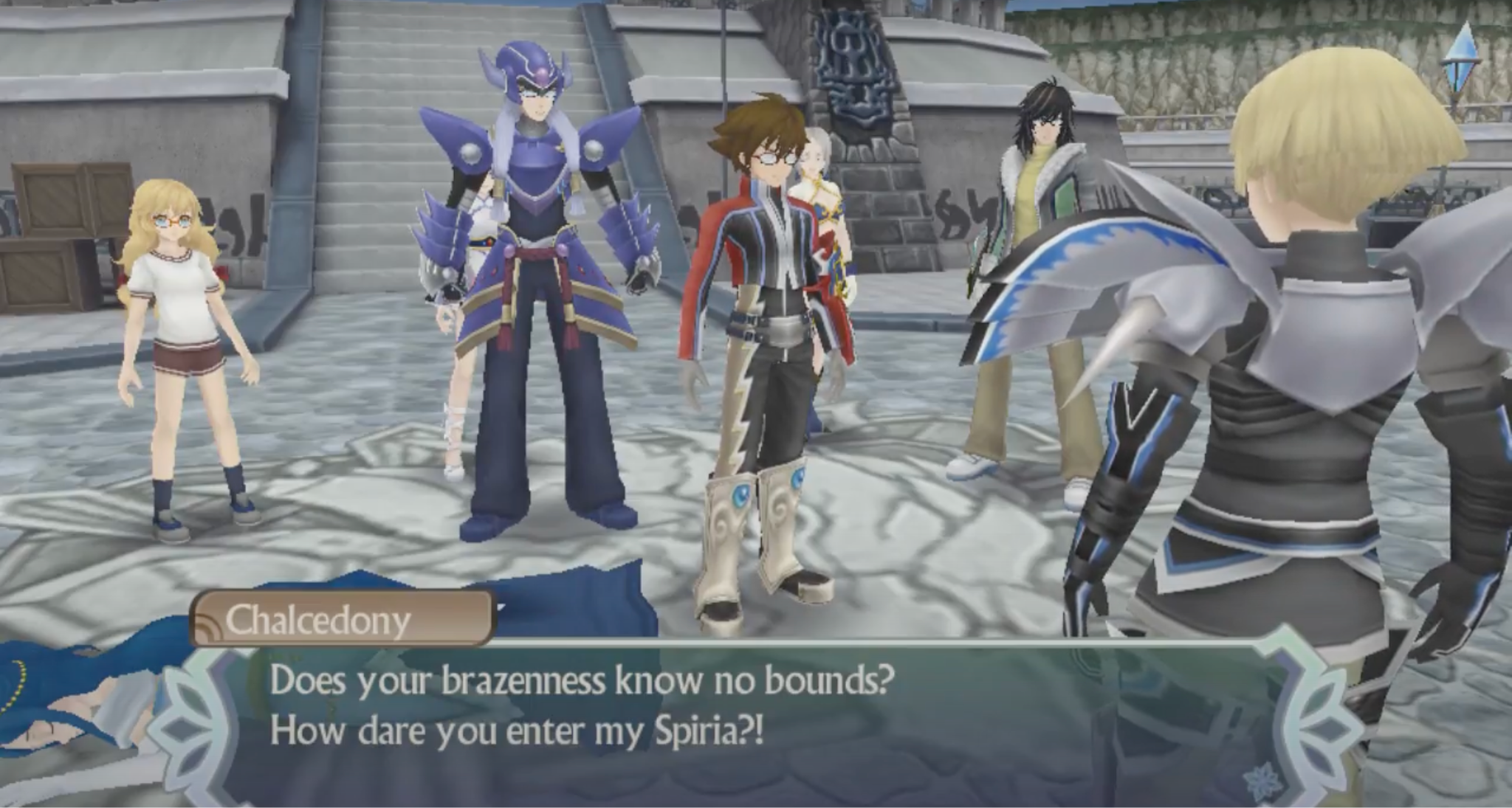

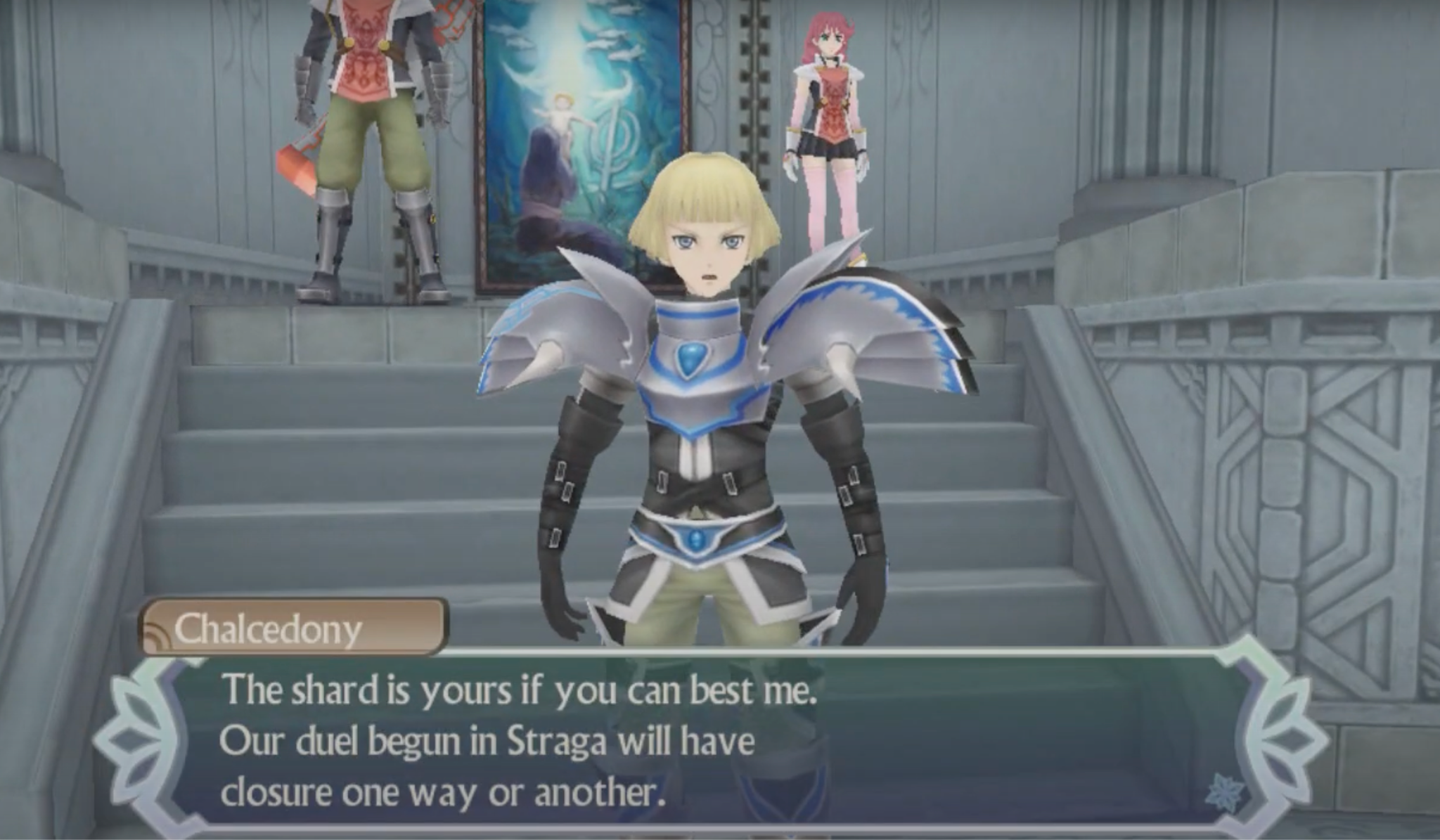

Speaking with Hisui when they enter Chalcdeony’s Spiria Nexus, Kunzite flatly states that his inner life depends on Lithia’s commands.

We feel the force of this in Kunzite’s procedural treatment of our hero’s party in their journey to reconstitute Kohaku’s Spiria Core, before Lithia returns:

- When Kunzite decides to formally join the group, his decision is phrased as a logical conditional that lays bare the primacy of Lithia’s well-being in his decision-making: “If I wish to revive my master,” he tells Kohaku, after learning that Kohaku’s Core shattered as a method of self-defense for Lithia, “I must make assisting you my top mission parameter.”

- After Kunzite saves the young Annaberg from a monster in Douze Mois Forest and she immediately develops affection for him, he gains the “Synthetic Spiria” title, featuring a first-person description that illustrates his indifference to all aspects of life beyond his directive to protect Lithia: “My Spiria is synthetic. Devoting resources to unnecessary tasks is irrational.”

- The game mechanics reinforce Kunzite’s fidelity to Lithia above all else—even the party and their shared mission to rebuild Kohaku’s Core—when he instantly transitions from a party member to a boss following a misunderstood exchange between Kor and Kohaku on the way out of Straga, mistakenly believing that Kor was responsible for “[his] master’s vessel [having] an incomplete Spiria Core.” Only in the wake of the battle and a proper explanation from Kohaku does his logical reasoning allow him to rejoin the party for Lithia’s sake.

Once Lithia’s Spiria reunites with her body and joins the party to rectify the mistakes of her past, her relationship with Kunzite opens the door to a beautiful evolution for Kunzite: because of their bond, Kunzite is able to become a person on his own terms.

In Lithia’s presence, Kunzite is awash with emotions, yet he insists that these merely derive from his programming, designed to make him a better guardian of his master. He supposes that his behavior of “a clear drop in performance” when he faces Chlorseraph, who is hell-bent on killing Lithia, “closely resembles the definition of fear”; he insists that he’d only told Lithia that her singing “warmed [his] heart” in their days on Minera “because [he] heard Fluora,” Lithia’s sister, “say [such things] to [her] previously.” But when he’s called to engage with those emotions as such—as when Hisui tells him to “[o]vercome” his fear—he retorts that “such behavior is beyond the parameters of [his] programming.” Though he was designed to emulate the inner lives of humans, he laments that he “cannot understand human emotion. I am merely a low-end machine into which a synthetic Spiria has been installed,” he tells Hisui and Lithia: cursed with the experience of emotions and will that originate not from within himself but rather from Lithia and his servitude to her. Despite having a human-like perspective, Kunzite seems no better off than Benston’s last painting: expressing emotions sourced from someone else, a “real” human, the final author of the creation’s essence and actions.

But the bonds between Spirias make something miraculous possible: Lithia can give Kunzite ownership over his feelings and thereby empower him to act independently of his original purpose. When Kunzite dismisses his commentary on Lithia’s singing as mimicry of Fluora, Lithia counters, “No, Kunzite—you chose those words to make me happy. There is no coincidence in that.” When she assures him that his fear is something he will overcome, she gives him a reason to believe in himself, couched in terms that his mechanoid logic can accept: “I am your master, am I not? If I say so, then you can trust it.”

Lithia gives Kunzite ownership over his feelings following their narrow escape from Chlorseraph.

By using her role as his master to convince him that he can actively participate in his relationship with her, Lithia gives Kunzite a paradigm for extending his inner life to people beyond his master:

- He is able to participate as one node in the village-wide Somatic bond, a network of connections that allows the free transmission of emotions between participating individuals, when the people of Dronning come together to hope for the future in the face of Gardenia’s emergence.

- In that same village, he discovers an old cook who’s fallen into possession of the same hot pot with which Kunzite cooked for Lithia on Minera thousands of years earlier, and he collaborates with him to cook exotic new dishes for the party, helping the cook to fulfill his personal dream of “extreme hot-potting.”

- In Blanche Villa, he “assimilate[s] the baking method into [his] long-term memory” for peach pie, Heliodor’s crowd-pleasing dish that unified the party, along with Pyrox and Peridot, during their first visit to Beryl’s hometown.

- Ahead of their adventure’s conclusion, he validates Annaberg’s affection for him and helps to emotionally heal Chalcedony’s father so that he might agree to officiate the long-overdue wedding of Annaberg’s parents, creating a new Somatic bond between them in the process.

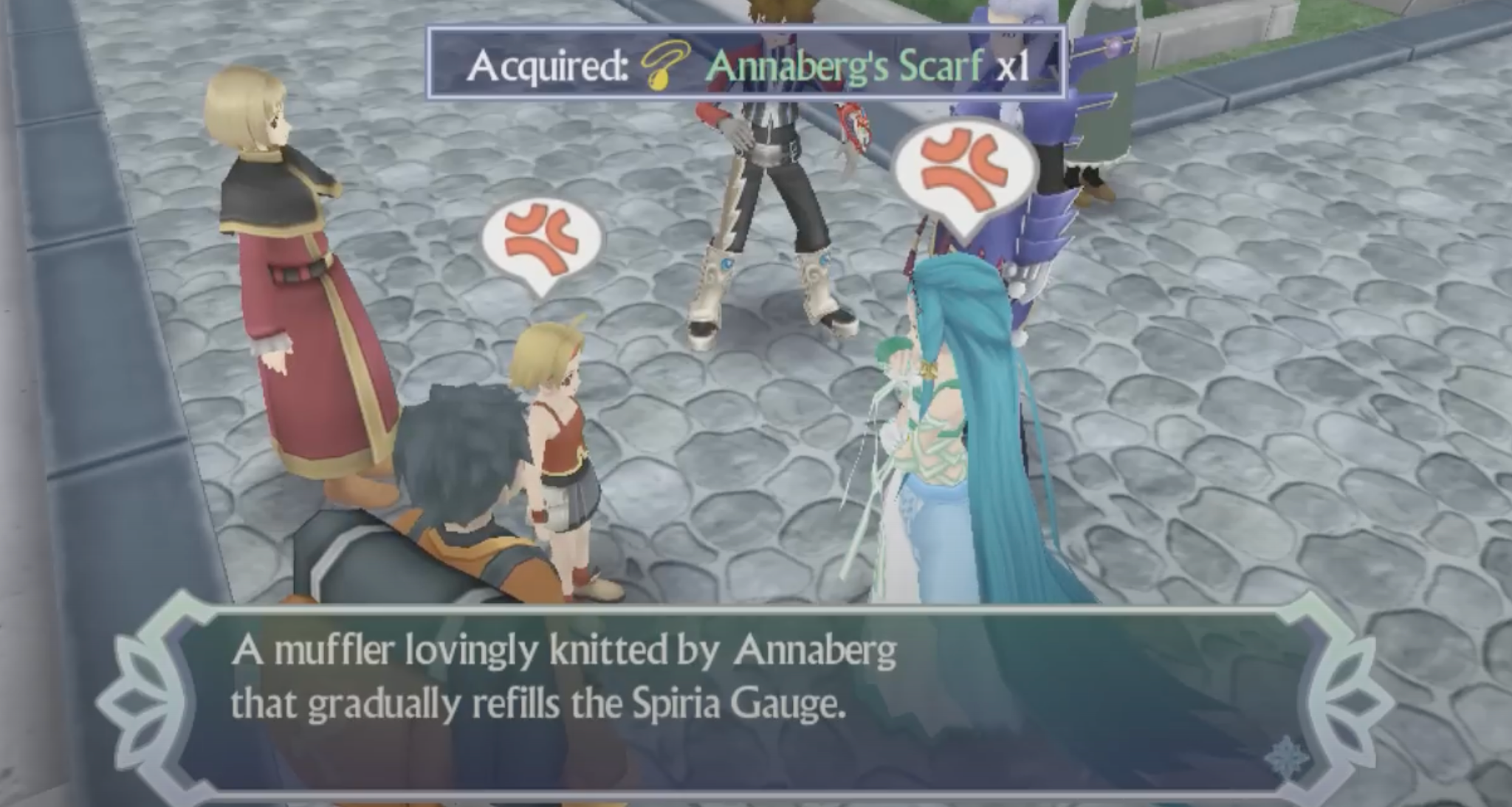

Each of these new relationships cultivates Kunzite into something more than Lithia’s servant because of his unique attachment to her. The Somatic bond in Dronning is something Kunzite must acknowledge, by Lithia and Hisui’s testimony, as validation of Lithia and Fluora’s wish to unite the Spirias of everyone in the world; even as Kunzite recognizes that his participation in the bond “defies all logic,” his master’s involvement in the achievement gives him the foundation to believe Gall when Gall tells Kunzite that “[j]ust because [he’s] made of parts doesn’t mean [his] Spiria isn’t real.” His history as Lithia’s sole cook equips him with a skill through which he can create contexts—meals—that relate participants’ Spirias to each other, not unlike a Somatic bond, leading him to realizations such as the wisdom of the hot pot—that “[i]n one diminutive receptacle, limitless possibilities arise both among the ingredients and those who cook them”—and the wisdom of the pie—that the “result” of a dish can differ based on preparation and intention, even if two cooks use “the exact same ingredients in the exact same quantities.” And perhaps most salient of all, his acceptance of Annaberg’s sentiments shows that he has come to accept the truth of Lithia’s belief that his feelings are things that truly belong to him: long after he initially rejected Lithia’s suggestion that “[his] kind Spiria can feel the warmth of a song,” he appraises the scarf which Annaberg knitted for him and says kindly that “[i]t was manufactured by hand and fueled by a heart filled with compassion. This scarf will warm my Spiria always.” And, indeed, he receives in the scarf a piece of equipment that mechanically does gradually refill the in-battle Spiria Gauge: a resource governing the party’s ability to activate Spiria Drive, a mode in which they tap deeper into their Spirias to unleash uninterrupted abilities and stronger techniques pointing to the essence of their character, like Mystic Artes.

Annaberg presents herself as Lithia’s “rival” for Kunzite’s affections with a hand-knitted scarf that refills the Spiria Gauge in battle.

Twice over, Kunzite and Lithia show us how the interaction between an artificial work and its creator can transform the nature of that work. Unlike Benston and his paintings, Lithia can express to Kunzite what she would like him to make of their relationship, empowering him to reconfigure his sense of self accordingly. And in a game so self-consciously concerned with the nature of artwork, it’s all the more fitting that she expresses this through another work of art. Whereas Kunzite was awoken by a poem that called him into servitude, Lithia opens his Spiria to others on Mount Bremen with a song of Fluora’s that invokes egalitarian connection:

Don’t fear the rain and close your eyes.

The dark won’t last forever.

Our Spirias will let us dream together.

We’ll fly over to the pale blue moon.

On shared wings we’ll soar to the light.

Now with this kiss, sleep tight.

Let’s go run under cover of night.

Though we may fight from time to time, you’ll wake with your hand in mine.

These words—invoked from Lithia’s bond with her sister, and passed along to her bond with Kunzite—invoke the ability of bonded Spirias to dream, bringing about possibilities and sentiments unbounded by the logic of reality or the conditions under which one was brought into existence. This guidance of his master in extending his inner sentiments from her to others in his life grounds Kunzite’s characteristics as a party member. Each party member’s combat abilities are governed by five cardinal attributes of their Spiria, four of which are common to everyone—Fight, Belief, Mettle, and Endurance—and one of which is unique to each character. Kunzite’s fifth attribute is Loyalty: an attribute that easily could have rendered him a senseless tool, instead—thanks to Lithia—elevated to a source of unparalleled strength to share with his friends.

The cardinal attributes of Kunzite’s Spiria, distinguished by the fifth attribute of Loyalty.

It is counterintuitive to discover an independent existence through a bond of servitude, but Tales of Hearts R tells us that this is exactly what it means to honor our relationships with others and find ourselves within those dependencies. And just as it did with Smithson and Striegov, it clarifies this lesson’s contours through portraits of characters that fail to learn it. In this case, we come to appreciate Kunzite through the cautionary tales of other mechaknights: Chlorseraph, who seeks total severance from masters; Clinoseraph, who strives to protect masters above all other relationships; Corundum, who takes her relationships with facts as her master; and Incarose, who interprets world purely through her love for her master. The lesson here, ultimately, is that the autonomy of a created entity is contingent on the creator genuinely investing in the creation and giving the creation a praxis for extending her values to people beyond her immediate network. When a work is nurtured by those who engage with it, as Kunzite is by Lithia and his friends, it can flourish into something with intrinsic value; yet when a work is cut off from the context of its creators and audience, or contorted by someone to serve an agenda that has nothing to do with the work per se, it loses not only its autonomy, but also the opportunity to become an irreplaceable, normatively significant node in a rich network of interpersonal relationships.

Lithia tries to make sense of Clinoseraph’s final effort to save Fluora’s bird prior to his calcification millennia earlier.

When our heroes eventually reach the calcified world of Minera, they discover the tragic history of mechanoids—not just through memories of their enemies’ upbringing, but also through a metaphor that illuminates the motives behind their creation. Our first introduction to Clinoseraph casts him as broken and calcified on the floor of Litha and Fluora’s room in te city of Cind’rella, frozen in a vain attempt to save a beloved seraph bird, a rare songbird Fluora had nurtured and kept in a cage—the cage now lying on the floor, a record of Gardenia’s inadvertent decimation of the planet millennia earlier. In the Seraph brothers’ memories of Minera, the party can find the very nest from which that fledgling bird fell, nestled in the tree where Fluora used to sing and tend to the city’s children. Looking at the nest, Kunzite and Lithia relate to Kor the story of how Creed noticed the fallen chick and flew into a rage at the thought that its mother “was unable to save its baby and just left it alone to cry all day long,” after which Fluora nursed the bird back to health and kept it as a pet.

Though the bird most obviously relates to Chlorseraph and Clinoseraph—the two defective mechanoids whom Fluora also took under her wing and raised as her own, even naming them after that same rare species of songbird—its story symbolizes the pathos and plight of mechanoids more broadly. Kunzite paints a picture of mechanoids as lacking in the eyes of their very creators: those that were considered “unstable” in fulfilling their functions—like Chlorseraph and Clinoseraph, whose namesake, the mineral clinochlore, is often considered “an uninteresting matrix for more important minerals”—were ordered to be discarded in favor of the more reliable xeroms, and “the final form of all mechanoids” is a hauntingly nondescript scrap heap of parts in a corner of Cind’rella, the pile where they are discarded “[when their] masters decide [they] are no longer useful.” From their moment of creation, mechanoids and mechaknights are subject to the capricious whims of their creators to justify their existence, like a fledgling whose mother brings it into the world yet cannot bring it back to the nest after its inevitable fall. Those fortunate enough to find a master who values them can justify their existence through their usefulness, and yet they are only justified so long as they’re conceived in relation to that utility—like a bird whose beautiful song emanates only from a cage, or a painting that becomes a senseless spattering of colors in our eyes as soon as we conceptually divorce it from the idea that it was authored by someone or artistically appreciated by someone.

In a memory of the past, Chlorseraph and Clinoseraph attempt to ease their master’s burden by stopping Creed and Lithia’s activation of Gardenia.

The “brother” mechaknights Chlorseraph and Clinoseraph suffer in the same cage of servitude to Fluora, though this bondage manifests in antithetical goals.

On the one hand, Chlorseraph feels the absence of his master—imprisoned far away within Gardenia, no longer able to influence him—and desperately clings to the notion of freedom as uniquely possible in such absence, obsessively seeking the death of Lithia so that “Kunzite’s Spiria can finally be free” and he can focus on “cultivating [their] beautiful friendship” rather than serving his master. Chlorseraph is like a flower that can only flourish in the shade, where Fluora is the sun: his urgent dependence on her absence betrays how central she remains to his self-concept, a relationship he implicitly admits when, as he lies dying from a surprise attack by his own brother, he calls out to Fluora, seeking the comfort of her embrace after all: “I don’t want to die. Help me, M-Master Fluora. I’m… scared.”

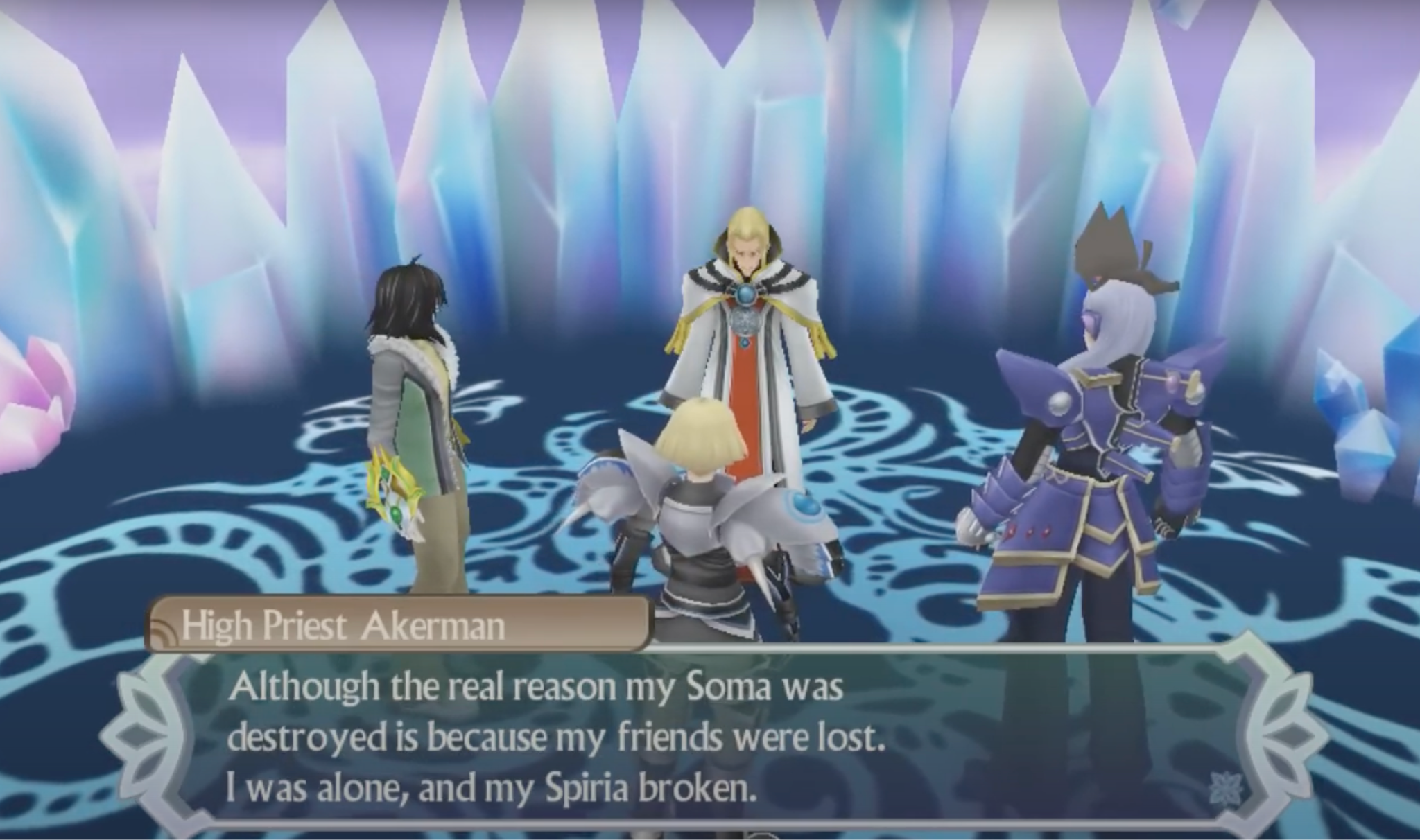

On the other hand, Clinoseraph declares as his raison d’être that “Master Fluora’s smile will be restored to this world. Her Spiria will be FREE!” Where Chlorseraph sought to free himself and other mechanoids, Clinoseraph’s entire Spiria Nexus, as the party witnesses, is “a nightmare without end” constituted by memories of Fluora’s suffering at the unwitting hands of those closest to her: her sister, Lithia, and the man she loved, Creed, neither of whom had faith in her vision of a world united under one cosmic Spiria. His Spiria, together with the vindictive way in which he imprisons Lithia within it, underscores that he sees everyone in the world as relevant only in virtue of their relationships with Fluora, only valuable in their contributions to his calculus of making Fluora happy. The sheer zealotry of his utilitarianism—killing his own brother because “[his] usefulness is at an end” once he no longer acts to protect Fluora—demonstrates, by contrast, that Kunzite wasn’t a mere tool even at the beginning of his journey with the party, far more fully actualized even at the outset thanks to Lithia’s guidance.

In his final moments, Clinoseraph curses his “inadequacy” that he “could not even save that little bird [Fluora] loved so.” The tragedy of the Seraph brothers is that the “little birds” they fail to save are themselves: alienated from their master’s support and with no community to guide them back to it, they are desperately trying to make sense of their relationship with her, to no avail—and with no means of accessing any authentic, autonomous self-concept through which to connect with others.

With his last breath, Clinoseraph curses his failure to save Fluora’s seraph bird.

Those mechaknights who ground their identities in their own feelings are no better off, so long as they’re cut off from the emotional support of their masters. At first glance, Corundum and Incarose look as if they ought to be better individuated than the Seraph brothers: Corundum is “motivated entirely by a desire to satisfy [her] curiosity,” and Incarose by love for her master, Creed Graphite. This kind of sentiment, directed outward toward others without essential reference to the master-servant relationship, looks like the right foundation to give an entity an inner life all its own. But while they are less existentially troubled than Kunzite, Corundum and Incarose are, by the same token, far more spiritually deficient: they lack a vantage point from which to interrogate their feelings and extend them to other people in their lives, leaving them in a solipsistic vacuum.

Incarose’s eyes are a heartbreakingly precise symbol: her very name, ‘Incarose’, comes from Creed, a tribute to the mineral he was reminded of when he gazes upon her “quite striking” eyes for the first time after creating her. And, just as her namesake mineral is constituted by carbon, the element that also constitutes graphite, those eyes unavoidably include their master in the mechaknight’s field of vision.

In the memory held by Incarose’s core, the party witnesses Creed, Incarose’s creator, seeing her for the first time and bestowing her name upon her.

Creed’s perspective on Incarose’s eyes frames Incarose’s perspective on the world: after noticing her eyes and naming her, he instructs her to “gaze at the world for the first time”:

Do you see how beautiful Minera is? And yet, it is sick with diseased Spirias and cannot survive much longer. Those eyes of yours are, in fact, Xerom Stones, and you must use them to support my xerom-evolution experiments! Together, we will make Minera a utopia!

The value Incarose is invited to see in the world, its beauty, is mediated through the very eyes which Creed fashioned to serve his goal of bringing peace to Minera through xeroms—the eyes in which Creed saw Incarose’s value. This is evident in the party’s most immediate experience of Incarose’s interiority, the memories bound within her Core: whereas the Seraph brothers’ Cores stored memories of their entire city at a key moment in Fluora’s history, Incarose’s contains only the initial interaction between herself and Creed when Creed first named her and gave her a purpose.

Creed’s judgment so thoroughly colors Incarose’s point of view that the question of what it means for her to serve her master, or to whom else she could relate, could never arise within her. On the contrary, the only “community” she forms redoubles her unitary love of Creed: whereas Kor amasses a diverse group of friends and bonds, Incarose is the antithesis, a 7-person “party” of identical mechanoid bodies; where Kor’s friends become more powerful by spending time together, learning about each other’s inner lives, and making new connections, Incarose becomes the monstrous “Incarose Alt,” disfiguring herself by objectifying the Seraph brothers, killing them and bolting their parts onto her body—staying bounded within her eyes’ field of vision, yet losing sight in both eyes by the time the party finally puts her to rest, overcome by the brothers resisting her will and vision even from within her own monstrous body.

As she dies, Incarose apologizes to Creed for losing her eyes.

Meanwhile, Corundum’s inner life is oriented neither toward a master nor toward any other human, but rather toward data: her overriding curiosity compels her to discover that which she doesn’t yet know. Yet despite not being tethered to a malicious director in the sense Incarose is, Corundum remains open to the manipulations of Creed because of the same shortcoming for which Kor criticizes Incarose Alt: “It’s because you’re alone. Your feelings—your Spiria—aren’t connected to anyone else.” Oriented toward information that isn’t itself grounded in specific human relationships or normative content, Corundum can easily be swayed and bound by humans who use her specialized attention for their own ends, channeling their goals through the focus of her attention like lasers channel light through her namesake mineral. In the Seraph brothers’ memories of millennia in the past, a Corundum bored by the operations of Mysticete upon its launch exclaims that data from Gardenia would be “more interesting,” giddily declaring, “Oh yeah, that’s GREAT! I’m gonna ask Creed to let me observe Gardenia! Wooooooo!” That curiosity lures her into becoming a tool for Creed: a disposable command core to operate Mysticete until it can take Creed to Gardenia, regardless of the unbearable pain this causes her Spiria.

Yet Corundum’s vulnerability also points the way to her redemption: in the absence of a master to color her value system and inner life, a benevolent person can take hold of her interests and show her a way to bond with the Spirias of others, just as Lithia’s role of master made possible for Kunzite. In fact, it’s Lithia who guides Corundum to this new path, too. Lithia uses a Will arte to free Corundum from Creed’s influence, stoking her curiosity in a new direction: she wants to solve the puzzle of why Lithia bothered to help her. This makes it possible for Lithia to provide her with new “data” by way of an answer: “all beings must live according to their own will,” she tells Corundum, “and not the will of others. They must answer only to the feelings that exist deep in their Spirias.” Not only does this give Corundum the standing to realize and admit that Creed “doesn’t care about [her] at all,” leading her to grant the party passage to Gardenia, but it also stokes her curiosity about the “weird sensation” she feels in response to Lithia’s help, prompting the party to Spiria Link with her. That Link grants Corundum evidence that she has a Spiria Nexus and is therefore capable of an authentic inner life, as well as evidence that she likes Lithia because of the kindness Lithia showed her—motivating Corundum “to study this new emotion as intimately as possible,” directing her innate focus of attention, her curiosity, inward and thereby allowing her to construct the diverse emotional network that the Seraph brothers and Incarose lack.

Within her Spiria Nexus, Corundum resolves to study the emotion that gave rise to her newfound, positive attachment to Lithia.

When Kunzite comes upon the mechanoid scrap heap in Cind’rella, he quietly says to the dismembered parts, “My brethren. Synthetic Spirias are not immune to error. It is my wish that one day humans and mechanoids might exist on a common emotional plane. If my present companions are a suitable test group, I estimate such a time will arise in the future.” Kunzite’s wish and judgment of his network of companions are themselves evidence that his estimation is well-founded. An artificial human whose self-concept fixates on its relation to the real human to whom it is bound will remain artificial, as will one whose perception of value in the world is solipsistic, providing them with no method for forging bonds with a range of individuals. But if the real human to whom the man-made object is bound affirms that creation’s ownership of its feelings and supports it in extending those feelings to objects beyond herself, as Lithia does with Kunzite, then the artificial creation can become authentically human. Gall crystallizes this conclusion at the end of their journey when he affirms to Kunzite, “You’ve got a real Spiria inside you, and that makes you legit.”

§1.3: Value in Artifice: Gardenia, Xeromization, Command Cores, and Bells

Tales of Hearts R tells us, then, that artificial works can not only represent the soul of their creator, but can cultivate and express a humanity of their own. But we might still doubt that these inspirited works really make some new contribution to the world beyond the values and intentions of the human from whom they originally derived: after all, even once he accepts his humanity, Kunzite’s cardinal attribute is Loyalty, and his novel expressions of humanity all bear hallmarks of his history and affection for Lithia.

It’s crucial to Tales of Hearts R‘s story and our engagement with it that the intentions and values of a created work can drift from those of its creator, often radically and unexpectedly. This calls those who engage with these works to uncover those distinctions, understand them, and reconcile them—lest the friction between creator and creation swallow up all life with which it comes in contact.

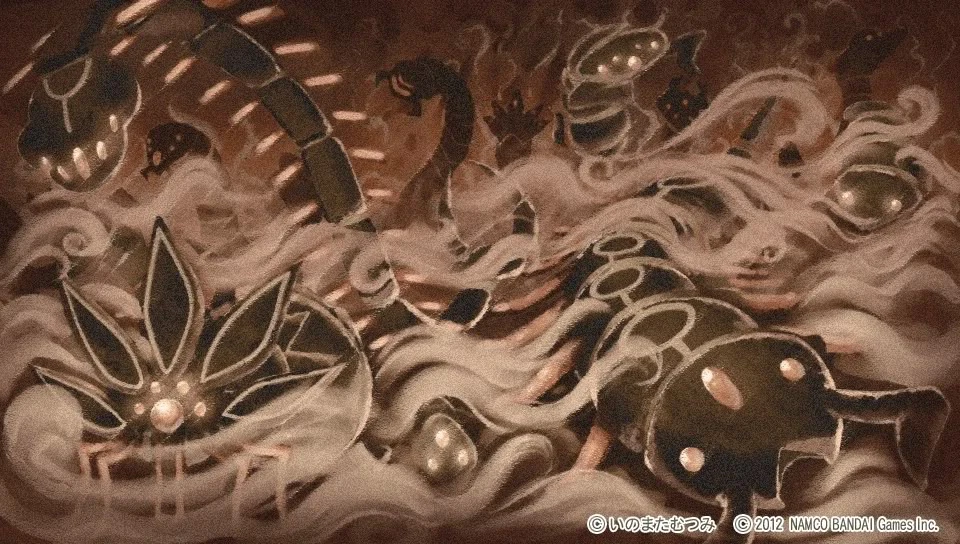

The “savior system,” Gardenia, emerges from the black moon and begins absorbing the Spirias of Organicans.

The key to completing the development of Gardenia—the “savior system” and “queen of xeroms,” with which the Mineran magical engineers Creed Graphite and Lithia Spodumene hope to eliminate the impulse to war from Mineran Spirias— was to make “[its] synthetic Spiria […] a copy of [Creed’s] own.” The final dungeon and principal threat of Tales of Hearts R is a representation of a human, similar in spiritual structure to Benston’s paintings despite being worlds apart in aesthetic value. Yet regardless of its status as a copy of Creed’s Spiria, the nature of Gardenia is foreign to Creed, its impulses beyond his control. Despite Creed’s insistence to Lithia that “I know myself better than anyone [and therefore] Gardenia WILL be controlled,” despite Creed’s having taken two thousand years to perfect the arte of merging with Gardenia’s Core so that “Gardenia might finally bend to my will,” Gardenia indiscriminately absorbs Spiria—including the Spiria of Creed’s beloved Fluora—with no regard to Creed’s conscious commands for it to act otherwise.

Lithia declares that “[t]he root of Gardenia’s uncontrollability lies in [Creed’s] primal nature,” which points to the mechanism through which, in Tales of Hearts R, artificial entities can deviate in their values and intentions from those of their creator or master: our inner nature, the game tells us, is pluralistic and opaque to us. It’s pluralistic in the sense that one person can value different ends—Creed seeks the restoration of Minera, the rescue of Fluora, dominion over the other world of Organica, a sense of belonging from the love of another—and opaque in the sense that a person isn’t necessarily consciously aware of all those values, nor of how they’re guiding her actions—the fact that Creed’s primal nature consists in “crav[ing] the love of someone[,] [o]f anyone[, without knowing] what love is” is a fact which Creed can be ignorant of, can deny, can discover, and can ultimately accept. Although Creed’s primal nature is a tragic deficiency, we’ve already seen that more positive natures can be inaccessible to creators despite being embedded in their works, like Benston’s last painting expressing his love to Beryl more directly than he can.

Creed is just as surprised as the party within the Spiria Nexus of a fused Creed and Gardenia to discover not only the Spirias of all the consumed Mineran life, but also a gaping black hole at the heart of the Nexus. That void is a topological reflection of Gardenia’s, and thus Creed’s, boundless impulse to consume in pursuit of “owning” a sense of love and belonging without fostering a genuine bond between the subject and object of that love. This, I think, is the reason that Creed’s total number of hit points is unknowable in both of his combat forms, remaining indeterminate (“??????/??????”) even if the party uses a Magic Lens to analyze his attributes and stats: if the analysis of an enemy consists in getting access to some understanding that an enemy has of its own abilities, then it makes a tragic and perfect sense that the party cannot understand a man who has fused with an artificial entity whose essence, though derived from him, is entirely foreign to his conscious conception of his identity. Only by defeating this mass of confusion can the party put Creed in a position to see the berserk vacuum of Gardenia for what it is, and what it is that he must accept and overcome: “the darkness of [his] Spiria.”

Creed suffers at the center of Gardenia’s Spiria Nexus, a vacuum of his own design which he can neither understand nor overcome.

The kind of distance between one’s actual identity and one’s self-concept, as we see with Creed and Gardenia, happens when we hypostatize our self-concept: that is, when we treat a mental model as though it were a real, fixed object rather than just a figure of speech or a heuristic to guide our patterns of thinking and acting. This is a deeply human impulse, and also a deeply artistic one. The artist who paints a self-portrait and takes it to illustrate some essential truth of her nature over and above the way she conducts herself is hypostatizing a concept of herself; someone who pursues a goal by vision-boarding, journaling, and dreaming so vividly that she experiences herself not simply as guiding her behavior but as actually trying to mold herself in such a way as to become some abstract, other version of herself which she has fantasized into reality is hypostatizing an alternative identity for herself. In either case, the person is ascribing reality to an artifact: a concept she has derived from certain aspects of herself, which bears the same sort of derivative relationship to her that an artificial being like Kunzite does to Lithia. Tales of Hearts R provides us with a robust illustration of both the positive and negative potential outcomes of hypostatization: by viewing xeroms as a means of individuals hypostatizing their self-concepts, we can understand the moral distinction between valuing a self-concept intrinsically and using it instrumentally for one’s external goals.

In Kor’s first encounter with a xerom within a Spiria Nexus, we look on as a Spore, seeded by Incarose, consumes Kohaku’s Spiria.

Our first introduction to the flower-inspired, Spiria-consuming creatures called xeroms is in the context of fairy tales, by which Organicans know them to be the “eaters of dreams” from the fairy tale of “Sleeping Beauty,” a history of Lithia enfolded within magical fiction. Our subsequent adventure across Organica and Minera reveals that this is a misunderstanding in the sense that xeroms are actually real organisms initially engineered by war-mongering Minerans to feed off of Organican Spiria and develop into living weapons. But there’s a further sense in which it’s a misunderstanding to call xeroms dream-eaters: ironically, they poison a person most thoroughly when they contribute to that person’s pursuit of a dream. In Creed’s pursuit of love, the xerom of Gardenia, fashioned after this desire, consumes all the Spirias of his fellow Minerans, treating them as fuel for that dream’s growth rather than entities with intrinsic value. And in the cases of villains like Kornerupine and Azide Silver who fall into possession of Kohaku’s Spiria shards, xeroms disfigure them in pursuit of more perfectly embodying the aspect of themselves that resonates with their respective shards: they xeromize themselves, willingly allowing xeroms to eat away at their Spiria, “pruning” their emotional range so the feeling grounded in the shard is all that remains. Kornerupine, bearing the Shard of Anger, crystallizes himself into an embodiment of resentment, fuming at his peers for not acknowledging the “brilliance” of his research; Silver, bearing the Shard of Love, seeks to conquer the world to make his comatose daughter, Lapis, a princess, consistent with her fantastical childhood wish from the days before Striegov stole her Spiria Core.

![Kornerupine objects to the party taking "[his] anger" away by reclaiming Kohaku's Shard of Anger.](http://withaterriblefate.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/word-image-9725-28.gif)

Kornerupine objects to the party taking “[his] anger” away by reclaiming Kohaku’s Shard of Anger.

Within Gardenia’s Core, the lost Mineran Spirias orient themselves through Somatic bonds with one another.

Because these artificial entities are capable of an authentic and intrinsic humanity, they’re the kinds of things with which humans can interact morally: by engaging with the artifact for its own sake, people can honor its intrinsic value, or they can punish it as a means of rectifying its immoral actions. And because of the nested structure of Spirias housed within these artificial Spirias, the moral content of humans’ interactions with the overarching artifice can cascade to morally impact those within it. This is what we witness, for instance, when Ines Lorenzen defeats the xeromized facade of Silver, listens to his confession of the guilt he feels for the fate of his wife and daughter, and affirms that she will help to support the health of his noble Spiria with her own: killing the artifice and enacting a Somatic bond with the embedded Spiria of the human Silver restores the nested human, empowering Silver to shed his calcified, xeromized shell like a snake shedding rotten skin. Even Spirias buried within a work so perniciously formless as Gardenia’s Core, Tales of Hearts R teaches us, can restore themselves and restructure the work by forming constellations of bonds with each other.

Ines, Silver, and Kohaku’s Shard of Love jointly restore Silver’s humanity.

This same mechanism explains how humans can accomplish morally significant outcomes in their communities by treating artificial Spirias in a supererogatory manner. We can now explain more precisely, for instance, the significance of Beryl adding Benston and Baaryl to Benston’s last painting. As Benston embedded his Spiria’s feelings for Beryl within the painting’s Spiria by representing Beryl within it, Beryl embeds her Spiria’s feelings for her family within it by adding them. Thus, Beryl transforms the painting’s Spiria from a representation of her grandfather’s into a synthetic conversation of their Spirias’ feelings for each other, embedded within a common context—making possible the bond between grandfather and granddaughter which can be understood by both of them in their subsequent meeting at the top of Blanche Villa even if they can’t express it in the outer world, beyond their shared inner lives made possible by the painting.

The party’s treatment of xeromized adversaries, Gardenia, and Benston’s painting alike reveal a useful lesson about the potential for positive outcomes from engagement with hypostatized self-concepts: by recognizing the real humanity that motivated a hypostatization and treating the artificial representation as a subject worthy of moral treatment in virtue of its relationship to that humanity, we can unravel those aspects of hypostatization that threaten to isolate the creator and instead turn the artifact into a medium that connects and conveys inner emotional content between those who engage with it and those who are trapped within it. Only by treating these objects with unconditioned respect can we avoid the risk of inadvertently reinforcing the aspects of hypostatization that isolate the individuals connected to the artificial object, a risk we see illustrated through the Mineran ability to act as a command core.

Two millennia before the start of the story, Lithia collapses during the initial activation of Gardenia, weakly asking for help after its avarice overwhelms her capacity to act as its command core.

The Mineran race has attributes and abilities which their Organican counterparts lack. Their crystalline, inorganic bodies weigh much more than Organican bodies (much to Lithia’s chagrin), they can separate their Spirias from those physical bodies, and they can act as “command cores” governing the operation of entities that are animated by Spirias. The game doesn’t explicate how these attributes and abilities relate to each other, but I think a reasonable explanation for all of them is that Mineran Spirias have the agency to fluidly channel themselves through the otherwise inanimate substances that can serve as vessels for autonomous life: substances like their bodies, and also substances like the brilliant stones constituting Spiria Cores, the emotional cornerstones of a human’s life. So, it’s no different for Lithia’s Spiria if she’s animating her physical, emerald-haired, stone body with it, or if she’s piloting Gardenia, or if she’s piloting Kohaku, taking control of her body to confront Creed after he emerges from his hiding place within Kor’s Spiria Nexus. That ability to effortlessly channel oneself into others might seem conducive to fostering new interpersonal connections, but Lithia’s history tells a different story. Things go so badly with the activation of Gardenia because Lithia tries to use this artificial Spiria as a tool for her own goals rather than trying to understand and support its intrinsic nature—and, by extension, Creed’s.

In this light, Lithia’s actions as a command core are the inverse of Striegov’s actions. Whereas Striegov objectified Spirias by focusing on their inherent qualities to the exclusion of their function, Lithia relates to Gardenia only through its function of absorbing aspects of Spiria, blind to the loneliness and the need for love which it inherited from Creed. A hypostatized self-concept like Gardenia is designed to accomplish something beyond what the source human from which it’s derived can: a self-portrait functions to inspire people to see its subject in a way that would not obviously follow from interacting with the person herself; a vision-boarded version of oneself causes its creator to act in ways conducive to becoming more like that different version; Gardenia is designed to selectively modify the Spirias of others. When we limit our focus to these functions, disregarding the human attributes that motivated their creation, we find ourselves engaged with machines that alienate us from reality and the potential connections latent within it. A self-portrait divorced from its human inspiration, a vision board divorced from its aspirant, and Gardenia divorced from Creed all point purely at the abstract notion of a dream: the function of changing making things other than what they are, with no content defining what reality is going to be changed and why—the opposite of the practical dreaming Lithia transmitting to Kunzite as a model for sculpting his further actions in reality. Lithia’s piloting of Gardenia, therefore, isn’t the kind of action that could selectively transform Spirias in the way she and Creed want; all it can achieve is the senseless application of the artifact’s operation to everything, regardless of its content or connection, explaining why a reified Creed self-concept that vacuums Spiria would vacuum all Spiria.

Fluora directs Lithia to join her in deactivating Gardenia using the Radial-Dream Will arte.

Even when she realizes the consequences of her actions and wants, with the best of intentions, to stop Gardenia, the only option available to the utilitarian-minded Lithia is to join her sister in an advanced Will arte, magic derived from the metaphysical force of Will drawn from a person’s Spiria, to seal Gardenia away without confronting the underlying problem. With Fluora commanding Gardenia from within and Lithia joining forces with her from the world beyond, the two sisters invoke the Radial-Dream arte, which inhibits Gardenia’s activity at the cost of putting them into a collaborative sleep. Just as much as when she was piloting Gardenia, Lithia’s method of stopping it is generic, abstracting herself and her sister away from reality to the realm of dreams in order to similarly remove Gardenia’s agency from reality, rather than addressing any of its particular relationships within reality. Only once Lithia returns to Gardenia at the end of Tales of Hearts R, enlightened by her journey with our heroes, can she use the hypostatization of Gardenia productively: naming the relationship between its void and Creed’s Spiria, and thus making Gardenia the kind of thing that can be censured, pitied, and forgiven, channeling Lithia and the party’s moral sentiments to all the other particular entities senselessly enmeshed within it.

Surprisingly, Tales of Hearts R tells us, we best appreciate and contribute to the lives and relationships of those creators and consumers connected to an artifact when we take the artifact itself seriously as an autonomous entity that warrants our moral consideration. When we do so, the values we find in our interactions with it naturally flow through, and evolve with, the values of its broader ecosystem. Case in point: when the party finally manages to locate, retrieve, and restore Shoalhaven’s Spiria-bearing Golden Bell, the same old man who had asked them to consider finding it elects to transform the value which the bell’s Spiria espouses. The old man initially expresses his one wish “to hear that Golden Bell ring one last time” as a final expression and memory of his homeland, the nation of Loweland, which was flooded and replaced with Shoalhaven by the now-dominant Organican nation, the Maximus Empire, in its hegemonic “War of Unification.” Yet when the bell hangs once again from the bell tower, the last standing remnant of the old man’s home, and Shoalhaven residents hear its beautiful tolling for the first time, the old man tells them that it’s “the Shoalhaven Bell,” not the Loweland Bell: he gives it a new identity, rather than invoking its old history, because, as he tells the party, he now sees it has the potential to express a value beyond the transmission of history: “[t]he people of Shoalhaven,” he says, “are moved by the sound of my people’s bell. […] Sometimes it’s best to draw a line under the past and look to the future.” By assigning a new identity to this artificial Spiria that holistically acknowledges its community of potential connections, he endorses within it a new value that allows it to spiritually connect the new Spirias of those in Shoalhaven and the old, fallen Spirias of those from Loweland, doing a moral good for the community by changing the normativity of the sound that rings out through the town.

The Golden Bell: formerly of Loweland, now the Shoalhaven Bell.

Let’s take stock. Tales of Hearts R, we’ve seen, offers a remarkably robust view of the communal agency of art. By situating its emotionally moving short stories, fables, and portraits in conversation with one another, we discover a sophisticated view of how interaction with such works can have direct and indirect human, moral content. Artworks and other man-made creations, in the most ordinary sense of those terms, can represent human spirits. Those spirits derive from the people who make and engage with those works, but the works themselves can take on autonomous value if those related to them honor and engage with them for the works’ own sake. When that condition is met, our engagement with those works can pass through to have morally significant consequences for the spirits of individuals and communities embedded within those works, transforming artistic engagement into a thick web of relationships between those involved in the work from outside it—such as creators, owners, and appreciators—and those within it—like the characters nested within a story, or the version of an appreciator which that appreciator projects inside of a painting.

Already, Tales of Hearts R has argued that our connections with artifacts like it and its characters matter in the same sense that our connections with other people matter. But as we take the actions that advance our heroes’ development and bring about a rich, granular diversity of these interpersonal connections, the game calls us to join its characters in analyzing what these interpersonal connections are: how they come in and out of being, how they evolve, and what grounds their value. This analysis points us to the greatest achievement of our playthrough: by playing through this game in the Tales of series that gains a fictional moral significance through our own analysis and understanding of the connections we form within that playthrough, we reach and establish a fictional metaphysical ground for the value of all interpersonal connections throughout the fictional and real people involved in the Tales of series.

§2: Soma Links and Somatic Bonds: Interpersonal Connection in Tales of Hearts R

Like art, bonds are not an object for us to possess: they are an activity for us to do.

When Clinoseraph awakens in Cind’rella after two thousand years of dormancy, he tells our heroes that he spent that time reliving the same memories of Minera’s downfall: “a nightmare without end.” Kunzite, not yet at peace with his own humanity, retorts that this statement is an “[e]rror. Mechaknights,” he reminds Clinoseraph, “cannot dream. You merely experienced a collection of signals stored in your memory.” “And yet,” Chlorseraph replies, “how different is that from the dreams, memories, and Spirias of people? Aren’t they all collections of signals?”

Chlorseraph challenges the distinction between the experiences of people and mechaknights.

We’ve seen that Chlorseraph is correct: in the fiction of Tales of Hearts R, there’s no essential difference between the Spirias of artificial entities and the Spirias of organic lifeforms. Rather, the key distinctions between Spiria-bearing entities come from differences in the “signals” which they transmit and receive, the bonds in which they participate. In asking us to study those distinctions, Tales of Hearts R involves us in a rich discourse on the chemistry of interpersonal relationships: consistent with its broader status as a fairy tale, it takes a concept that’s so simple as to be a cliché (“those two people have chemistry with each other”) and undergirds it with the explanatory structure to render it illuminating, emotionally resonant, and useful.

Kohaku’s Spira Core, unified.

As with many games in the Tales of series, the names we encounter throughout the world are a precise set of constraints carving the fiction’s metaphysics at its joints. In the case of Tales of Hearts R, these names imply to the player that she can form better relationships by approaching bonds scientifically, analyzing how they form and update based on new data under a controlled set of conditions. We see a stratification of lifeforms between organic life—our more familiar model of human and animal life—on Organica, and mineral life—that less familiar model of flexible spirits that channel themselves fluidly in and out of inanimate matter—on Minera. But the names of people, both “real” and “artificial,” from both worlds regularly derive from real-world elements and minerals, suggesting that this stratification is a distinction without a difference. To list just a sampling, some of which we’ve already seen:

- The Mineran Lithia derives from the alkali metal, lithium.

- The mechaknight siblings Chlorseraph and Clionseraph take the distinguishing aspects of their names—those not drawn from Fluora’s inspiration of the seraph bird—from the chlorite mineral clinochlore.