The following is an entry in Tales of Praxis, a weekly series studying the storytelling and philosophy of Bandai Namco’s Tales series through written analyses and streamed playthroughs of a wide range of the Tales games on With a Terrible Fate’s Twitch channel and YouTube channel.

The linear storyline of Tales of Symphonia opened my world more than any “open-world” game.

(Spoiler warnings for Tales of Symphonia, BioShock, and Nier.)

Think back to the first serious video-game story you played, before you were a seasoned gamer with expectations of how games are designed and what you’re expected to do in them. At that moment behind your controller, you were innocent in the best of ways: not guiding your avatars’ actions based on where other games had trained you to predict the game was going to go, but rather making decisions based on the present moment in the game and the motivations its premise alone had given you and those avatars.

Tales of Symphonia was this game for me. At eight years old, I played it and learned that video games can tell stories—and that those stories can make meaning out of our own expectations just as much as they make meaning out of their characters’ journeys.

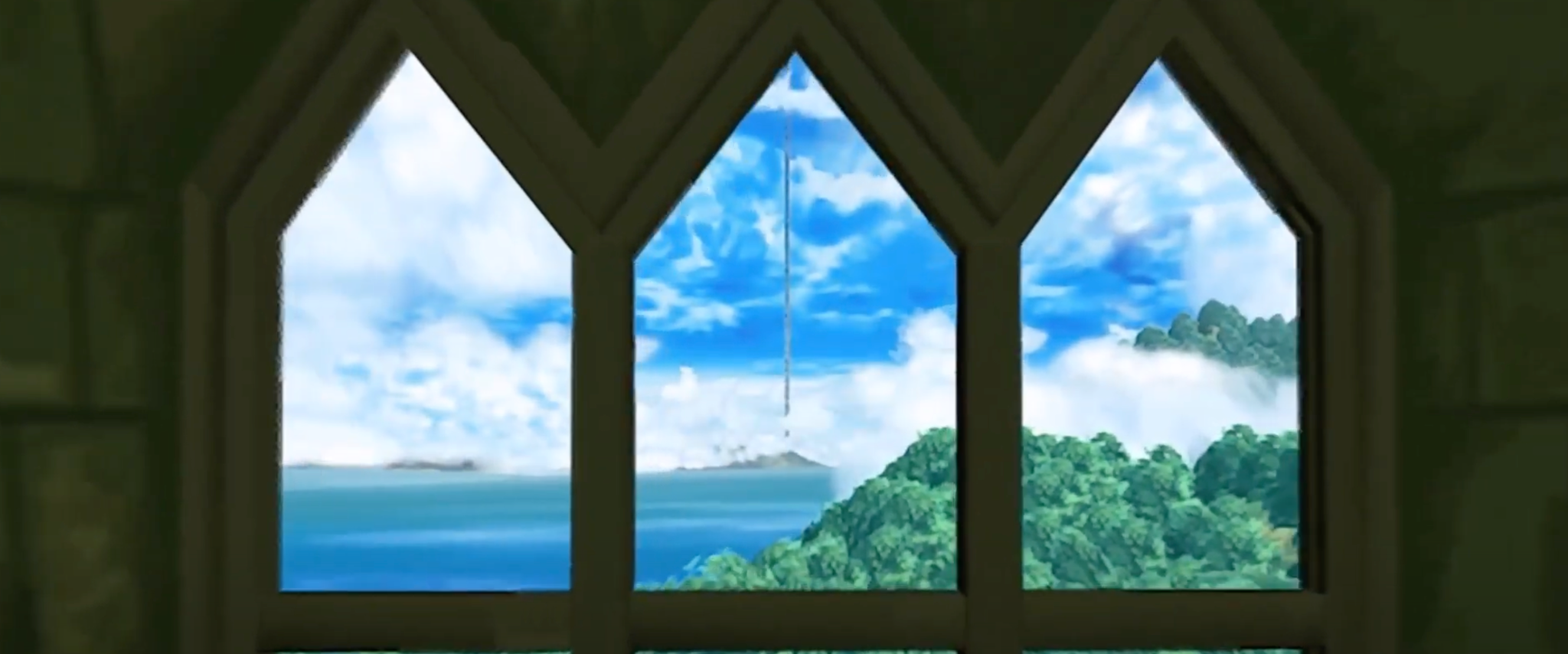

The first in-game appearance of the Tower of Salvation in Sylvarant, marking the path of the Chosen One’s Journey of Regeneration.

Especially within the canon of Tales games, Tales of Symphonia sends its heroes and players off into the world with a relatively simple premise: the world is in a state of decline, and the Chosen One, descendant of angels, must go on a journey across all of Sylvarant to regenerate the mana of the declining world and seal away the Desians who have been wreaking totalitarian havoc upon humanity. Few of the specific mechanics or consequences of the quest are known to the characters at the outset of the Journey of Regeneration, and so it’s easy for the player to treat it as more mythological than realistic: as a child, I was completely willing to jump into this plotline as an analogue to Christ’s biblical journey to redeem humanity. Particularly when Colette, the Chosen One, is characteristically devout, and her friends and teacher have been raised in a town deeply embedded within the traditions of the Church of Martel, there’s not much of a vantage point from which to even question this mythos within the game for its first several hours.

Once you play a number of JRPGs, you develop an intuition for the norms of the genre, just as you would for mystery novels or superhero movies: you expect that your party will end the journey after no fewer than sixty hours, facing off against a god-like entity, most likely in some far-off metaphysical realm they couldn’t have imagined at the start of the story. But without that model in your head, a journey to save the world can be exactly what it looks like: Colette and her entourage of guardians travel the whole World Map of Sylvarant, learn about previous Journeys of Regeneration, release the Seals to regenerate the world and mold Colette into an angel, and confront the depths of Desians’ inhumanity in the course of liberating and destroying human ranches.

Colette expresses the resolution of a savior to Lloyd in Triet as they begin the Journey of Regeneration in earnest, setting the context for the first part of the player’s journey as well.

As an adult with a sensitivity to JRPG stories and plot twists, you can see how further plotlines quietly suggest themselves in those first hours of the game, like the existence of a group that resembles yet is distinct from Desians (the Renegades) and a secret super-weapon with no obvious relation to the Chosen’s quest (the Mana Cannon); as a child navigating a world with a wide range of towns, characters, and side-quests, though, it’s intuitive to keep yourself tethered to the world’s reality by focusing solely on that Journey of Regeneration, particularly when the characters in your party do the same—and particularly when the game’s mechanics, lacking more modern “quality of life” guidance systems that point to your next destination, virtually require you to hold the primary quest and character motivations in your mind in order to keep track of where to direct the party next. The Journey of Regeneration is sufficiently long and cohesive to make the uninitiated player feel as if it really were a satisfying and complete story, with nothing waiting beyond the Tower of Salvation.

This was my mindset during my first Tales of Symphonia playthrough two decades ago, when Sheena first stood up in front of the rest of the party and told them that she was from another world. Following the release of all four Summon Spirit Seals in Sylvarant, when the Chosen has lost her voice, Sheena picks a quiet moment at a campfire to find her own voice, and Raine—quick on the uptake, as ever—charges her to “Tell us about your homeland. A land that doesn’t exist in this world.” Similar to Raine and Colette’s description of the Journey of Regeneration at the start of the game, Sheena’s description of Tethe’alla is relatively simple and unadorned: she speaks of “another world that lies entwined with Sylvarant, as shadow is to light,” and tells her Sylvarant friends that Sylvarant and Tethe’alla “can’t see or touch each other, but they do in fact exist next to and affect each other,” with the flourishing of one implying the decline of the other.

Sheena introduces the party to the concept of her homeland, Tethe’alla.

I can’t overstate how radically this revelation impacted me as a new gamer, and, twenty years later, I think it stands the test of time as a distinctive kind of twist for the player of a video game. Nowadays, we’ve become accustomed as gamers to plot twists that change the valence of our actions in the game in unexpected ways: BioShock reveals that our actions with our avatar were actually serving the goals of the game’s villain; Nier reveals that we were actually having our avatar slaughter humans when we’d thought he was culling monsters. It’s true that Sheena implies that our actions on the Journey of Regeneration have had a negative impact we hadn’t previously gleaned, but for me, the most immediate reaction to her exposition wasn’t that my actions in Tales of Symphonia thus far were villainous. Instead, I felt as though those actions were what we might call “wrong-sized”: we spent upwards of ten hours traveling a full world in service of that world’s monolithic religion and in opposition of its totalitarian oppressors, only to discover that we had been limited to half of the world. Because our mission as a player was initially defined in morally unambiguous terms of saving the world, we find ourselves in a similar situation to Colette at the end of this campfire conversation: not in a position to reject Sheena, nor in a position to abandon the Journey of Regeneration, but rather at a total loss for what to do next, needing to appeal to Remiel—the party’s source of truth for the meaning of the Journey of Regeneration—to determine the morally good action in light of both worlds.

Despite all the twists and revelations that happen once the party first reaches the Tower of Salvation, I was more thoroughly disarmed by the subsequent journey to Tethe’alla than I was by Remiel and Kratos’ deception. Sheena’s explanation of Tethe’alla was the reason for this: we learn that there is a parallel world totally inaccessible to us, beyond the domain of our journey to save the world, and then we suddenly find ourselves in that parallel world with no objective except undoing the impact that our quest to save the world has had on Colette (her Angel Toxicosis, and the loss of her soul). Tales of Symphonia doesn’t offer its players a wide range of different paths through its world and story in the way that an “open-world” game like Skyrim or The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild does, but it left more of an impression on me in terms of what it feels like to “freely” make decisions within the world of a video game. After spending between ten and fifteen hours in a seemingly self-contained world on a quest literally motivated by an Oracle, we arrive in a world where that destiny doesn’t apply; rather than going along with a clear hero’s mission, as Lloyd and all his friends did, we now have to proceed along a storyline without a clear sense of moral compass or success conditions.

Kratos, in his role as an agent of Cruxis, meets the party in Tethe’alla and implies how far beyond the pale of their destined quest they’ve already gone.

Nowadays, we tend to judge the freedom we’re afforded in games proportionately to the range of activities we can explore in their worlds at any given time: you have more freedom, this view suggests, if you can decide whether to confront Ganondorf, or cook a meal, or build a house, or go rock-climbing, and so on. This is one face of what many have described as ludonarrative dissonance: when we can take a wide range of actions in a game that don’t seem to all equally align with what the avatar is motivated to do within the narrative (for example, making a sandwich when there’s a princess to save), we discover friction between how the game presents its story and the story we actually end up telling through our actions. Yet, if we want to feel a sense of freedom as players, we might think ludonarrative dissonance is a necessary evil: without all of those vectors of choice, wouldn’t we simply feel as if we were experiencing a movie, occasionally pushing buttons to little narrative effect?

Twenty years ago, Tales of Symphonia taught me that this is a false dichotomy. By changing the context of a long game’s story from a comprehensive quest for salvation to a journey that fails to accommodate the totality of the game’s world, we discover the overwhelming freedom of diverging from destined heroism at the same time, and for the same reasons, that Lloyd and his fellow Sylvarant natives do. As with many of the game’s sidequests and relationship mechanics, this journey along its main quest shapes our experience as players in ways we discover organically: precisely by treating the game innocently, as a world rather than an instance of a genre, we experience our own arc of reevaluating our actions and role in the world just as the characters do, without the artifice of external guidance or infinitely explorable paths.

Sheena speaks up about her origins for the first time.

Sheena’s confession of her origins encapsulates the power of Tales of Symphonia’s particular breed of linear storytelling. There is a sense in which she cannot speak up until Colette loses her voice. Even before we learn that the Desians and Cruxis are two sides of the same coin, the Journey of Regeneration presents itself as hegemonic just like the Desian’s oppression: with our path through the world determined by a literal Chosen One who is unimpeachably beneficent, there’s no space to act according to a different perspective; small wonder, then, that Sheena is coded as an enemy and assassin when she first meets the party. It’s only once that narrative is muted that Sheena is empowered to share her origins and change the meaning of the path we’re walking together. When she does change its meaning, true to the convictions that undergird Tales of Symphonia’s moral universe, the party is quick to adjust their expectations, pursuing the best possible outcome even if they don’t know what it is—and partnering with like-minded individuals to bring that outcome about, regardless of the gulfs between their identities. Only a short time after she was trying to assassinate Colette, Sheena desperately exclaims that she wants “[a] way for Sylvarant, Tethe’alla, and Colette to all be happy,” and Colette, despite being born and bred for the purpose of fulfilling Sylvarant’s Journey of Regeneration, immediately volunteers that she will ask Remiel how to save both worlds. For me, this ethos embodies a different kind of “open-world” storytelling: one that forces the player and her party alike to become more open-minded as they continue pursuing a singular mission, giving each other the opportunity to share their histories and perspectives and change the bearing of that mission’s linear path midstream.

We never stop walking in Tales of Symphonia, but, with the same resolve that we undertook the Journey of Regeneration, we walk into a different world.