The following is a Critical Review focused on The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake. Critical Review is a series in which With a Terrible Fate’s video game analysts critically evaluate the work of themselves and other analysts, with the goal of advancing our collective understanding of video-game storytelling. The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake is a series that analyzes how and why the remake of Final Fantasy VII is a landmark innovation in both Final Fantasy and video-game storytelling more broadly.

While other incomplete games were being recalled, Final Fantasy VII Remake was teaching a master class in how to tell a story that was brilliant precisely because it was incomplete.[1]

(Spoilers are ahead for Final Fantasy VII Remake, Final Fantasy VII, and Six Characters in Search of an Author.)

As appreciators of modern video-game stories, we have every reason to be anxious about games whose stories appear to drop off at the end, leading the game “to be continued” in a sequel or DLC: the cynics among us have plenty of evidence for game series that appear to have used this manner of incompleteness simply as a way to make gamers buy two things rather than one in order to get the full story that they were promised when they bought the first thing. However, just as Dark Souls and Bloodborne challenged cynics by creating compelling stories that could only be told as DLC, Final Fantasy VII Remake has shown how a game with an incomplete plot, when structured correctly, can represent cohesive and satisfying themes that wouldn’t be as well-represented any other way.

I want to convince you that the way in which the finale of Final Fantasy VII Remake leaves its plot unfinished is what makes possible the theme that Aerith describes as “boundless, terrifying freedom”: it liberates its characters not only from the player’s expectation of what story they are participating in, but also from the very concept of belonging to a story. While this might initially seem like a very esoteric achievement in storytelling, we’ll see that this theme is not only one that other storytellers have tried to achieve over the years, but also one that succinctly represents many of the core ideas at work in Final Fantasy VII.[2]

I begin by reviewing the reasons that I initially worried it would be impossible for Final Fantasy VII to be remade as multiple games; the twist is that the way in which Final Fantasy VII Remake reconceived of Final Fantasy VII uses those very same reasons to make its own story uniquely tractable. With this background in view, I show that the finale’s sequence of (1) battle against the Whispers, (2) battle against Sephiroth, and (3) Cloud’s encounter with Sephiroth at the Edge of Creation undoes not only the plot of the original Final Fantasy VII but also any context that the player could use to situate the game’s characters within a story. Finally, I show how this unusual twist on episodic storytelling offers unexpected explanations for a wide range of elements in Remake, from the meaning of the final confrontation with Sephiroth to the relationship between the Planet and the Lifestream.

How Final Fantasy VII Remake interrupts Final Fantasy VII’s story

Final Fantasy VII Remake set itself apart by taking advantage of a storytelling limitation that I initially worried would totally undermine it.

When Square Enix first announced that its remake of Final Fantasy VII would be episodic rather than a single game, I responded with an article explaining my fear that the basic nature of video-game storytelling, combined with the apocalyptic nature of Final Fantasy VII’s plot, meant that a multi-game remake of Final Fantasy VII was inappropriate despite the fact that the original PlayStation game spanned three separate disks.[3]

My basic argument to that conclusion was this: video games’ stories are fundamentally interactive in the sense that the events in their plot depend on the player to come about.[4] If a single story is split over multiple games, then either (1) the totality of a player’s choices and the consequences of those choices are maintained across all of those games, in which case those are not really separate games but rather one game split across multiple “disks” (like the original Final Fantasy VII), or (2) subsequent games in the series disregard at least some of the player’s choices made in earlier games, in which case the series is not really a single story split over multiple games but rather a collection of related but different stories.

I pointed out that this challenge to turning one game into many games is even more acute in games that have a feature I called “apocalyptic narrative teleology”: stories in which the actions of the player all tend to drive the world toward a conclusion that radically changes the nature of the game’s entire world, “ending” the world with which the game began and creating a totally new one. I noted that this kind of storytelling is not an essential feature of video-game storytelling but rather a very popular kind of video-game story, particularly within the world of JRPGs—and, more to the point, FFVII is an example of this kind of story because the player’s struggle against Sephiroth, together with Meteorfall, radically and irreversibly changes the structure of the Planet.

Meteorfall, the world-changing climax of Final Fantasy VII.

The combination of these storytelling attributes in Final Fantasy VII, I argued, meant that it simply wouldn’t be possible to split the agency of the player across multiple games in a way that successfully represented Final Fantasy VII’s apocalyptic kind of story:

it’s implausible to suppose that the causal influence of a player extends across multiple games, such that the very same actions made by a player in one game directly influence the world of another game. […] [It] is oxymoronic to design a game that both stands on its own and is a direct extension of a different game.

[…] [If] the entirety of a game’s universe, insofar as the player causally impacts it, is essential to the game’s narrative, then video games will be aimed (at least partly) towards making their own universes meaningful. In order for a game to do this while retaining a sense of cohesion in its narrative, the game’s story must address the totality of its universe on its own terms—that is to say, the game’s narrative must not stretch beyond its own universe. For to do otherwise would be to make a game whose narrative focuses on a universe other than the game itself, and it’s not obvious why or how a narrative could address something other than its own universe.

Granted, I also noted in that article’s conclusion that “if the remake ends up simply being some sort of reimagining or retelling of the FFVII series, then such a new story could be exciting”—which, in hindsight, I recognize to be an understatement. What’s especially “exciting” about the conclusion of Final Fantasy VII Remake in this regard, though, is that its reimagining of the original’s story doesn’t merely circumvent the challenges of splitting one story into multiple games: it also uses the very aspects of video-game storytelling that I highlighted above to make its cliffhanger sort of ending uniquely meaningful.

Quite to the contrary of my initial fears, Final Fantasy VII Remake turned out to be a game with an “unfinished” plot that, for that very reason, stands alone as an artwork that grants its characters an unprecedented degree of freedom, regardless of whatever may happen in Final Fantasy VII Remake 2 and beyond.

The upshot of the video-game-story dynamics I outlined above is that the extent of a player’s direct influence on the story of a game is limited to those events that are contained within the bounds of the game. In ordinary cases where a complete story is represented by a single game, this observation is almost too obvious to mention—of course we wouldn’t expect, for example, the player of Ocarina of Time to continue exerting influence over Link’s life after the defeat of Ganondorf—but the observation becomes more interesting when a plot is left half-finished at the conclusion of a game. At the end of games that fall into this less ordinary category, players find themselves in the peculiar situation of having directly brought about all the events in the game’s plot yet, for the reasons I just discussed, knowing that the events that will continue the plot in a subsequent game will be indifferent to the player’s impact on the first game. Most of the time, this will just lead to a frustrating sense of discontinuity in games that try to split what ought to be a single story into more than one game; in the case of Final Fantasy VII Remake, though, this termination of the player’s agency at the end of the game makes possible an unexpectedly literal interpretation of Aerith’s warning about Cloud and his friends changing fate by defeating the Whispers and Sephiroth: winning those battles empowers the characters to change themselves, rather than to be changed and manipulated by the player, by virtue of advancing into a section of the plot that exists beyond the bounds of the game and is therefore outside the purview of the player’s agency.

But the termination of the player’s agency at a cliffhanger moment in Final Fantasy VII Remake’s plot is just one aspect of makes this “boundless, terrifying freedom” possible; to fully appreciate the degree to which this game’s unusual ending liberates its characters, we need to situate that termination of agency in the broader context of the Whispers, Sephiroth, and—of all things—the storytelling value of cutscenes.

Final Fantasy VII Remake’s Triad of Narrative Freedom

To understand how Final Fantasy VII Remake liberates its characters in an unsettlingly thoroughgoing way, we need to first ask and answer two similarly unsettling questions:

- What does it even mean for a character to be free?

- What would it take to tell a story in which a character achieves freedom?

These might initially seem like the sort of idle question that only literary critics would care about, but they drive to the heart of what a decent amount of more modern and experimental literature concerns itself with—and when we reflect on the substance of these questions, I think we’ll find them more relatable than we’d initially believe.

My personal favorite example of this type of literature outside of video games is Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author.[5] The play features a theater company that, in the middle of a rehearsal, is interrupted by six characters that have been abandoned by their author and are in desperate need of actors and a director to tell their story. As the play evolves and the actors bring the characters’ story to life, the lines between reality and fiction blur ever further, with the characters discovering aspects of their relationships and history that may not even have been part of their original, intended story—up to and including the death of one character, The Son, which ends the play, ambiguous between being part of the character’s story and something spontaneous and “real” that happened during the enactment of that story.

The characters and theater company staging the characters’ story in Act III of a Tavistock Little Theatre production of Six Characters in Search of an Author, London, 1948.

There’s plenty more to say about Six Characters in Search of an Author, but I only bring it up (1) to point out that these seemingly obscure questions of the lived experience of characters in stories have literary precedent well beyond Final Fantasy and video games, and (2) to illustrate that studies about the nature of characters can be more illuminating than we might expect. The fact that characters are designed and bound to enact stories designed by others (i.e. authors) facilitates any number of interesting meditations about what it is like to feel as though one has no agency over one’s life or the “story” one is living. (Not to mention that, in the case of Final Fantasy VII Remake, we’ll see that this study of characters directly informs much more central and less esoteric themes within the game.)

With that in mind, what does it even mean for a character to be free? Fundamentally, a character is basically a representation of a person (what Mieke Bal calls a “complex semantic unit”) that’s used by an author in a story to express certain themes, lessons, emotional experiences, or whatever other goals of storytelling you might favor.[6] Within that fictional, representational framework, a character can have motivations and act for certain reasons—but these are all selected by the author for the ultimate end of expressing the goals of the story as a whole. So, for our purposes, what it means for a character to be free is for that character to act from motivations independent of the story within which they are embedded.[7]

That brings us to our second question: what would it take to tell a story in which a character achieves freedom? Six Characters in Search of an Author gives us some guidance here: as Pirandello does by making his audience confused as to whether the play’s six characters are living out their story or are otherwise creating something new and unscripted, this kind of storytelling needs a way of distancing characters and their actions from the authorial forces that are presumed to have created those characters. To achieve this, a story needs to distance its characters from three concepts:

- Characters must be distanced from authorial intent. If the story in which a character is embedded retains the sense that its plot has been architected by an authorial entity for the purposes of expressing certain kinds of narrative meaning, then the characters, as constitutive elements of that plot, will retain the sense of being directed by an authorial entity for those same purposes.[8]

- Characters must be distanced from audience expectations. Even if it’s not clear what an authorial entity may have been expressing through a story, an audience that has reason to believe that they know how the story’s plot is going to evolve will believe, to the extent that they are right, that the characters are acting in service of that plot rather than of their own volition. Adaptations of well-known stories are illuminating examples in this case: if I’m watching a production of West Side Story and know that it’s an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, I can have the sense that its characters are bound by and acting in service of Romeo and Juliet’s plot archetype without having any idea what the authorial entity behind West Side Story is trying to express through it.

- Characters must be distanced from having narrative valence in their relationships with one another. By narrative valence, I mean dispositions that irreducibly pertain to a story that is being told by an author to an audience. For instance, in a story featuring a king and a usurper, the latter of whom is the story’s protagonist, those characters stand in a relationship with narrative valence: by virtue of the usurper being the protagonist and the king being essentially antagonistic to the usurper (simply because of what a king is and what a usurper is), the story’s audience can (1) not know what the story’s authorial entity is trying to express and (2) not have expectations as to the precise plot that the story is going to enact yet still believe that the universe of possible plots will be defined by this protagonist-antagonist relationship between the king and usurper, in which case their actions would be guided by the parameters of that narratively valent relationship rather than their intrinsic motivations.

The high bar of these desiderata—what I’ll collectively call the triad of narrative freedom—may make it seem impossible for characters to ever truly seem free within the context of their story. That’s exactly why it’s so remarkable that the disparate elements of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s finale came together in such a way that they perfectly met the burden of this triad, giving the game’s characters the “boundless, terrifying freedom” that Aerith portends.

This happens in a three-step journey that the characters take in the last chapter of the game: (1) the battle against the Whispers, (2) the battle against Sephiroth, and (3) the cutscene between Sephiroth and Cloud at the Edge of Creation.

The Battle Against the Whispers

The Whispers of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s finale slyly trick the player into defeating her own expectations of how the plot of the game is supposed to evolve.

Cloud faces Whisper Viridi, Whisper Rubrum, Whisper Croceo, and Whisper Harbinger.

In my article explaining how the Whispers allow the player of Final Fantasy Remake VII to challenge fate in an unprecedentedly relatable way, I argue that the game establishes a tight analogy between Whisper Harbinger and the player of Final Fantasy VII, thereby forcing the player of Remake to defeat her own expectations of how the plot will evolve in order to bring about a world in which the characters can live out a different plot:

Like Whisper Harbinger, the player of a video game presides over its world while (in most cases, and certainly in the case of Final Fantasy VII) remaining unreachable, beyond the ken of its inhabitants. Like Whisper Harbinger, the player of a video game guides its world’s trajectory from a distance. Like Whisper Harbinger, the player of a video game only does battle and can be fought by proxy through the medium of an avatar or a party, whom she appears to control in some non-specified way. And, like Whisper Harbinger, the player of Final Fantasy VII has a stake in Cloud and Midgar’s story going a certain way: namely, we expect it to conform to the narrative of Final Fantasy VII since we played that game, brought its outcomes about, and saw that, within the universe of that game, things couldn’t have turned out any other way (i.e. there were no “multiple endings” for us to access, altering the fate of the world).

So, in the epic climax of a story that we thought we knew very well, the Whispers that we once thought to merely be interesting narrative manifestations of a game’s “invisible rails” are revealed to be perfect metaphors for our own expectations of and stake in the way the story went the first time: without consciously reflecting on it before our confrontation with Whisper Harbinger, that version of ourselves that played and knew Final Fantasy VII was guiding us along the expected path of the game’s story. Then, upon this final confrontation, the game challenges us to metaphorically defeat those expectations and create a Final Fantasy VII world in which things could be otherwise than they were in the original game.

By defeating the Whispers, defined by the Assess Materia’s skill as being connected to and defenders of “all the threads of time and space that shape the planet’s fate,” the player distances Final Fantasy VII Remake’s characters from audience expectations that the plot will evolve in accordance with the outcomes of Final Fantasy VII. We leave this confrontation, then, with one third of the triad of narrative freedom satisfied.

(While it’s not essential to the argument here, it’s worth mentioning that the appearance of the Whispers—faceless, amorphous creatures with the sole purpose of enforcing the plot—is an apt foil for Cloud and his friends to confront as they try to achieve true freedom. The Whispers are characters wholly defined by and fully subordinate to the plot, which makes them the ideal augur of, to paraphrase Red XIII, what would happen to the characters if they were to fail in their battle against the Whispers.[9])

The Battle Against Sephiroth

To defeat Sephiroth at Destiny’s Crossroads is to undermine the very notion of his villainy.

Sephiroth manifesting from a confluence of Whispers, following the defeat of Whisper Harbinger.

When I first played Final Fantasy VII Remake, I found the final battle against Sephiroth to be one of the most challenging puzzles that most urgently demanded explanation. It’s not obvious why Sephiroth—little more than an ethereal presence guiding Cloud throughout most of Remake—chooses that moment after the party’s escape from Shinra HQ and defeat of Whisper Harbinger to confront them. It’s not obvious what his threat is: he appears to cast Meteor during the battle even though there’s no reason to suppose he has the Black Materia yet, so it’s not clear whether it’s truly threatening the planet or merely acting as some more metaphorical threat to the party in the metaphysical space where the battle happens. And, perhaps most unsettlingly, it’s not obvious what the reward for defeating Sephiroth is.

In the original Final Fantasy VII, there is a complicated but clear explanation of how Cloud’s bond with Sephiroth, via injection with Jenova cells, leads him to inadvertently serving Sephiroth’s plan and ultimately finding and defeating Sephiroth. It might be tempting, therefore, to try to apply this explanation to what happens in the Sephiroth confrontation in Final Fantasy VII Remake; in my view, though, this is ultimately a fool’s errand. While it’s evident that Cloud struggles with Sephiroth’s influence over the course of Remake, the best explanation we have available within the game of the Whispers (from the Assess Materia and Aerith) identifies them as agents safeguarding the fate of the Planet, ostensibly by virtue of connection to the Lifestream (“the threads of time and space that shape the planet’s fate”), whereas Jenova is explicitly understood to be an alien, invasive lifeform on the Planet. Because Sephiroth’s appearance in the final confrontation not only happens on the other side of a metaphysical portal effected by an accretion of Whispers but also appears to show him and the Whispers mutually channelling each other, it seems murky at best and tendentious at worst to try to infer the role of Jenova in the original Final Fantasy VII as an explanation for how the party arrived at this particular confrontation with Sephiroth or what the meaning of that confrontation is.

Sephiroth channeling the Whispers at the climax of the final battle between him and the party.

What is clear about the context of the final battle between Sephiroth and the party in Final Fantasy VII Remake is that the Whispers are evoking and defending the plot of the original Final Fantasy VII and Sephiroth, the ultimate antagonist and final boss of the latter game, is the entity they’re channeling as the “final boss” in defense of that plot. Remake, as Adam Bierstedt rightly notes in his article on apocalypticism in the game’s narrative, “is completely framed by Sephiroth’s presence,” yet characters beyond Cloud barely register any knowledge of him (besides Aerith, who presumably recognizes the threat of his relationship to the Planet). Sephiroth is primarily known by Cloud, bearing his (presumably jumbled) memories and other imprints from their time together, and the player, who, similarly to Cloud, imports her assumptions and background experiences about Sephiroth without a firm basis for knowing that those data obtain in Remake.[10]

When we look at the sentiments expressed by Sephiroth throughout Remake, his primary stated objective is to heal the dying Planet: this is the focus of his very first encounter with Cloud, and it colors their final conversation in the game (we’ll turn our focus there in a moment). Meanwhile, it’s not at all clear why Sephiroth wants to confront Cloud and the gang at Destiny’s Crossroads: the only invitation he offers before stepping through the portal to the metaphysical playground of the Whispers is to tell Cloud that he’s “waiting.”

What we do know as players is that in the final confrontation of Final Fantasy VII Remake, deep within the lair of metaphysical entities that are singularly concerned with bringing about the plot of the original Final Fantasy VII, those narrative-enforcing enemies bring about a final battle against the original game’s final boss.

This has two consequences:

- It primes Cloud and the player to interpret Sephiroth as the ultimate antagonist of Remake, even though the rest of the party has little reason to naturally arrive at this conclusion given the plot of Remake itself.

- It creates the opportunity for the party to defeat Sephiroth in the middle of the plot that will presumably unfold from the combination of Remake and its follow-up games, thereby undermining the ability for Sephiroth to function as the ultimate antagonist of the overall Final Fantasy VII Remake series.

The Whispers—presumably in an effort to enact the outcome of the original plot after Cloud manages to defeat Whisper Harbinger—effectively “skip ahead” to the end of the plot, trying to bring about the resolution of the original game (Meteorfall). However, that means that when Cloud and his friends defeat Sephiroth, they too have “skipped ahead” and defeated what the player took to be the game’s main antagonist in a game that represents only the first portion of the original Final Fantasy VII’s plot. That leaves the player with an interesting quandary: now that Sephiroth’s been defeated so early in a way that seems closely analogous to his endgame in the original, he seems unable to function as the ultimate antagonist for the entire series that they assumed he would be—particularly when the scenes with Sephiroth that preceded this confrontation, as well as the scene that follows it, provide little basis for that framing of him.

Now, the player has defeated Sephiroth and inadvertently distanced him from the narrative valence his relationship had to other characters: after his defeat at Destiny’s Crossroads, it’s become hauntingly unclear exactly what role the still-very-much-alive Sephiroth will play in the remainder of the series—and indeed, perhaps even more frighteningly, the version of Sephiroth we’ll see next, at the Edge of Creation, seems almost relieved to have been freed by Cloud and the player of the traditional narrative valence ascribed to him by the Whispers, raising the question of what he will do now that he is no longer bound by that role.[11], [12]

With two thirds of the triad of narrative freedom satisfied, then, the player moves with Cloud and Sephiroth to the Edge of Creation.

The Cutscene between Sephiroth and Cloud at the Edge of Creation

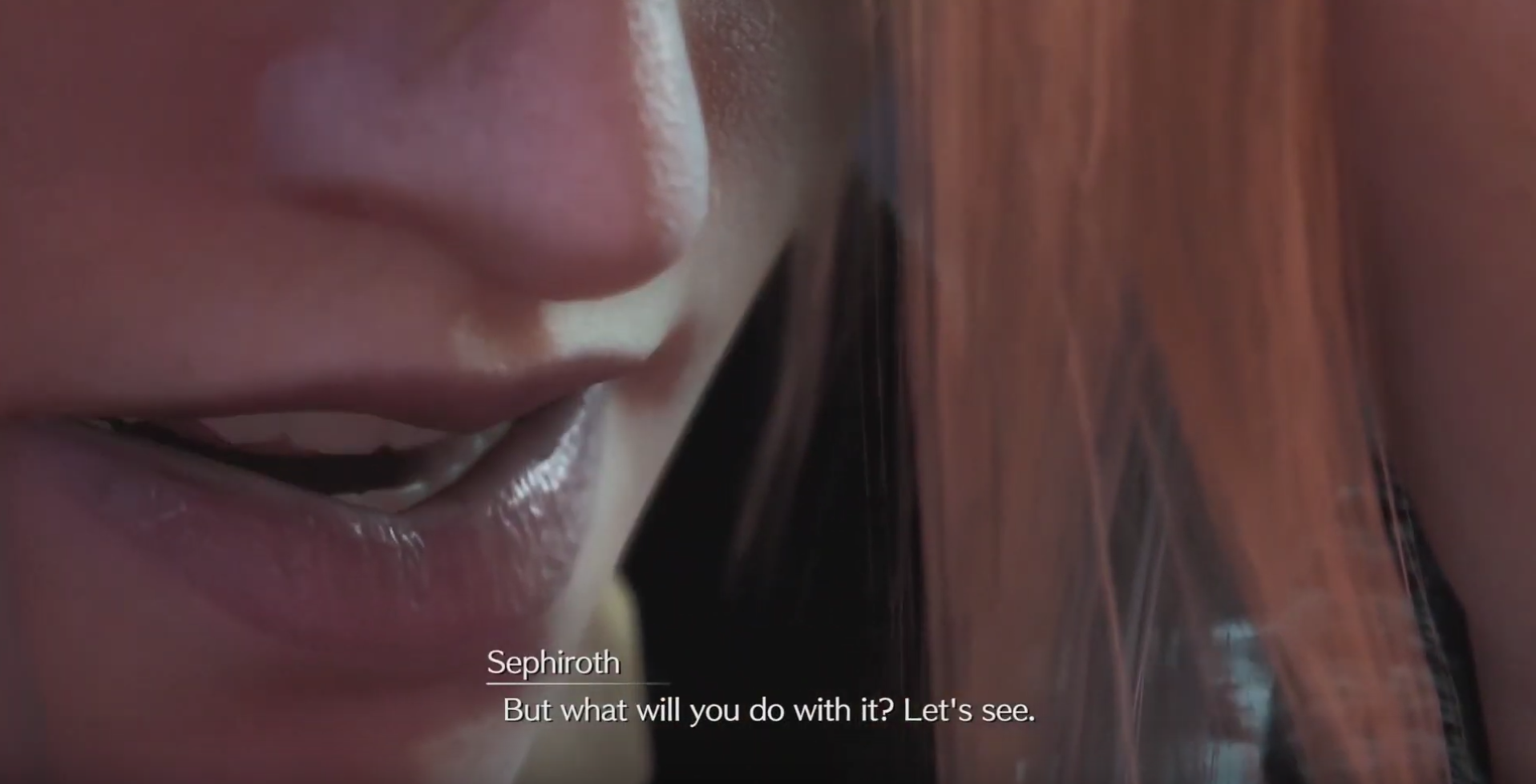

The non-interactive scene between Sephiorth and Cloud in the galactic precipice that Sephiroth calls “the Edge of Creation” is less than three minutes long, but, as the last step in Cloud and his friends’ path to “boundless, terrifying freedom,” it speaks volumes.

I mentioned this scene in my previous article on the Whispers in the context of Sephiroth’s observation that “that which lies ahead does not yet exist,” a doubly salient remark in view of both (1) the original Final Fantasy VII’s plot being nullified by the party’s defeat of the Whispers and (2) the fact that, by virtue of this marking the end of the game, the next installment of the plot literally does not exist within the world of Final Fantasy VII Remake. In the context of liberating the characters of the game, though, this scene has two other key features that leaves players totally adrift and the characters on the path to a hauntingly authentic kind of agency: Sephiroth’s new motives and the cessation of player agency.

First, as if Sephiroth himself had been waiting to be released from his original role by virtue of being defeated at the Crossroads of Destiny, he invites Cloud to join him in defying destiny. Especially to the player who has played the original Final Fantasy VII and expected Sephiroth to occupy his same archetype as the final boss, this appeal to Cloud ought to be extremely unsettling. The apparent collaboration between the Whispers and Sephiroth in the previous stage of the finale made it all but obvious, lack of evidence from Remake notwithstanding, that Sephiroth intended to bring about the same plot he had enacted in the original game; now that he has been defeated, however, he doesn’t have the air about him of a bested villain grasping around for an alternative plot: confident that all possibilities other than the original plot are now metaphysically possible, he seems eager to change destiny with Cloud. With “Sephiroth the Final Boss” undermined by his earlier defeat, this new apparent motivation of his casts his desire to help the dying Planet, which he expressed at the beginning of Remake, in a different light.

Of course Sephiroth could ultimately end up having a different apocalyptic scheme up his sleeve, but that’s not the point: the point is that, within the context purely of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s story, with the pre-existing framework of Sephiroth of an antagonist undermined by the defeat of the Whispers and Sephiroth himself, we as players simply cannot know what his intentions are in the plot from this point on. We’ve been robbed of the grounding to interpret him as a character—and that confers freedom upon him and his subsequent role in the plot that is beyond our ken as players of Remake.

And—to the second point about this encounter—even if we had a firmer sense of Sephiroth’s new identity at this moment, we would be powerless to do anything in response. We have arrived at the moment where the game’s shrewd interruption of plot and cessation of player agency, which I discussed at the outset of this article, come in to tie the bow on the present of boundless, terrifying character freedom: at the beginning of this encounter, Sephiroth takes Cloud’s hand when Cloud reached for his sword, as if to underscore the formal fact that this is a cutscene: a moment of non-interactive video-game content in which the player is forced to watch events unfold and characters take action without any input from the player. This is the moment when, for better or worse, true freedom is achieved: Cloud’s actions are beyond the scope of the player, underscoring the more foundational fact that, because this is also the end of the game, the subsequent events of the plot, and the character’s actions therein, are also, for the reasons we considered at the outset, beyond the reach of the agency of the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake.

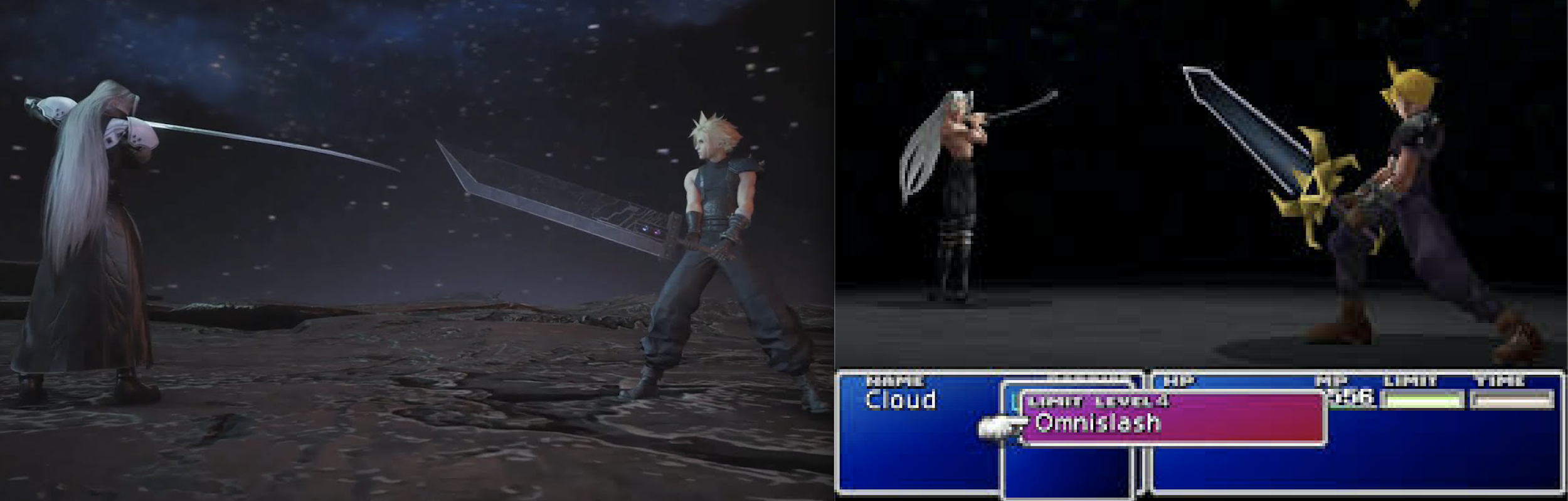

The mirror between Cloud and Sephiroth’s confrontations at the Edge of Creation in Remake and the Northern Crater in the original Final Fantasy VII (shown above) is especially illuminating in this regard. Final Fantasy VII concludes with two battles against Sephiroth: the first featuring the party against him, and the second featuring a one-on-one battle in which the player directs Cloud to use the Limit Break move Omnislash to defeat Sephiroth. This second battle is poignant and pertinent to our analysis for two reasons:

- Putting the ultimate defeat of Sephiroth in the hands of the player, who chooses for Cloud to use Omnislash, underscores Cloud’s newfound agency and the fact that, rather than acting as a pawn or extension of Sephiroth, Cloud is now standing up to Sephiroth and asserting his identity.

- The fact that the player is able and prompted to make Cloud defeat Sephiroth with the Omnislash move even if they Cloud hasn’t “earned” that Limit Break in the broader universe of the game (i.e. by obtaining it as a Battle Square reward, making it available as a Limit Break in all battles) underscores that at the conclusion of the game, the player is using her agency to enact a specific, inevitable plot: the only possible conclusion of Final Fantasy VII is that Cloud defeats Sephiroth with Omnislash, and it is up to the player, as the agent bringing about the plot and determining Cloud, to make that happen.[13]

In contrast, while Final Fantasy VII Remake also concludes with two confrontations with Sephiroth, the latter of which is one-on-one between Cloud and Sephiroth, the second battle is beyond the reach of the player: there is no singular outcome, no purely protagonistic Limit Break to deploy, and no narrative closure of the kind we experience in the Northern Crater. Instead, we see two characters sparring with each other on equal footing, their motives determined not by the player, nor by an authorial entity. Their intentions are so opaque that it is disingenuous for us even to suppose the authorial intent of where their relationship will evolve next, completing the triad of narrative freedom.

At the Edge of Creation, Cloud and Sephiroth battle each other for reasons ultimately inaccessible to the player; they do so of their own volition rather than the demands of the plot. When Sephiroth disarms Cloud and wonders aloud what Cloud will do with the “seven seconds till the end,” his sentiments echoes that of the player: through the uncanny exercise of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s final chapter, we have found ourselves in a position where our very own actions have liberated its characters from our influence, granting them a freedom unmatched even by the characters of stories like Pirandello’s—a freedom so genuine that our former avatar, standing there uncertain in the face of Sephiroth’s words, seems unprepared to act on it.

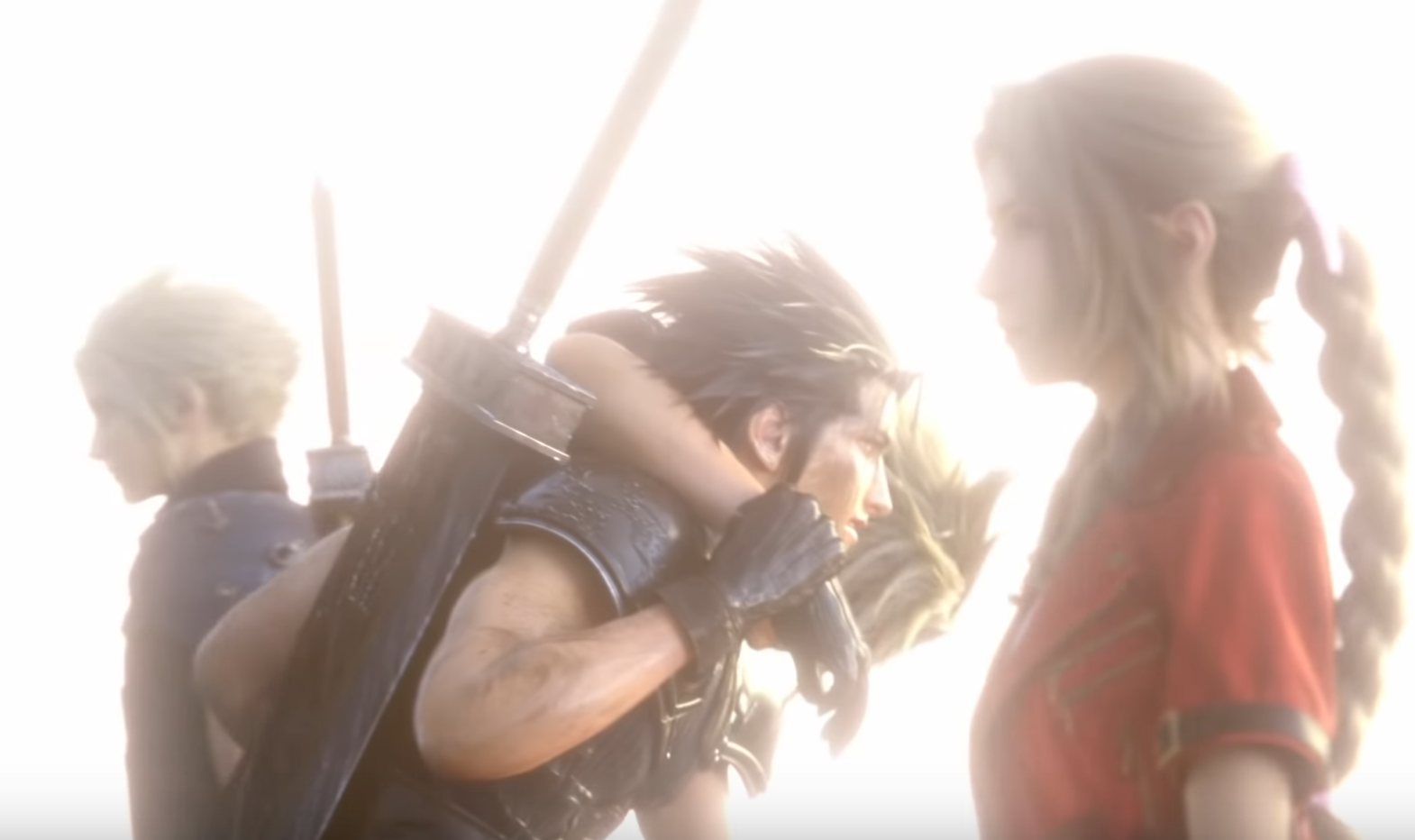

What about the fact that there will be another game following up on Final Fantasy VII Remake in which the player will presumably exert influence over the characters and plot: does this cheapen, or otherwise render fleeting, the radical freedom imputed to the characters at the end of this first entry in the Remake series?[14] No: the precise impact of ending this first game in the middle of the plot after this sequence of events in the finale is a severance of the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s agency from the characters’ actions. As I discussed at the outset of the article, the interruption of the plot at the end of this game means that the actions of this first game’s player will, by virtue of the mere structure of game narrative, not be able to determine the evolution of events in the portion of the plot represented by later games—even if the same flesh-and-blood person assumes the role of the player in those later entries in the Remake series. While I think this kind of character liberation makes the first Remake game a fascinating meditation on freedom in its own right, it equally invites us to get excited about what it will mean for players of Final Fantasy VII Remake 2 to step in and use their agency to direct a party that, by virtue of the first game, has experienced a deep kind of narrative empowerment known to few, if any, characters before them.

Toward Intrinsic Value

The manner in which Final Fantasy VII Remake’s finale undoes traditional frameworks of meaning around its characters grants them the exact kind of freedom that Aerith foretells at Destiny’s Crossroads. This freedom is boundless in that the characters, after the events of the final confrontation against Sephiroth, are able to act outside the construct of a plot. This freedom is terrifying in the sense that it puts those characters—characters from one of the most teleological, fate-driven worlds in modern storytelling—in the position of acting on their own maxims, an ability which, by definition, puts their intentions beyond the realm of that which the player of Remake can know at Remake’s conclusion.

When small nuances in continuity suggest that characters like Zack Fair, dead in the original Final Fantasy VII, may in some sense be alive in the world of Final Fantasy VII Remake after the defeat of the Whispers, it’s missing the point to suddenly infer the existence of multiple timelines and suppose that players have suddenly “jumped” to an alternate universe or distinct “continuity”: the challenging and revolutionary storytelling consequence of the confrontations against the Whispers and Sephiroth is that Remake ends at a moment when, by its own admission, there is more plot to come, yet that plot could evolve in any direction. Particularly by highlighting the fact that Zack—the character whose death in many ways incited the events of the original Final Fantasy VII—could be alive, the game underscores how truly unknowable the future of its plot is: players and authors alike, for that moment in the evolution of the series, have absolutely no standing to determine how characters will act next—nor, indeed, even which characters will obtain in or pertain to the plot still to come.

We ought to take the game’s narration at its word when it ends with the promise that “The Unknown Journey Will Continue.” This doesn’t just mean that the Remake series will represent a journey distinct from the journey of Final Fantasy VII: this means that, by virtue of the player untethering the game’s character from the very concept of plot and story, the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake cannot know where the journey will go next: they are caught between the knowledge that the plot must continue and the understanding that, as Aerith said, the party’s defeat of the Whispers has endowed them with the capacity to change themselves in an act of true self-determination. Final Fantasy VII Remake 2 could go in virtually any direction—a fact underscored by the volume of plot speculation in which players have engaged in the months since its release—and whatever direction it ends up actually going in cannot alter the vast universe of possible plots and character actions left on the table at the conclusion of the first Remake.

While this act of liberating a story’s characters is intrinsically interesting and remarkable, it also invites us to explore one of the Final Fantasy VII series’ core themes, intrinsic value, from a radically new perspective. Whether we’re considering the identity of Cloud, the influence of Sephiroth, or the nature of the Planet, the Final Fantasy VII series constantly challenges us to consider what something is essentially worth versus how that thing is used or contingently valued by other people and entities. Cloud constructs a makeshift self-concept out of bits and pieces of Zack, himself, and Sephiroth following deep personal trauma; in the original Final Fantasy VII, it takes Tifa conducting a metaphysical reconstruction of his mind to help him form an authentic self. Sephiroth becomes confused about the identity of his parents and diffuses himself across a network of clones that are at once subordinate to his will and yet also aspects of his self-concept. The Planet, despite being a singular, living entity, is also constituted by a manipulable stream of life with a particular energy and trajectory—the kind of thing that everyone from the Cetra to Shinra to Sephiroth manipulate for good and evil reasons alike.

A representation of Shinra’s Mako reactors siphoning energy from the Planet for their own ends, as shown in a Shinra HQ propaganda video.

At bottom, all of these characters and entities have meaning and value that is not contingent on others; one of the main thematic challenges of Final Fantasy VII is working to recognize what that meaning and value is while simultaneously understanding the relationships in which those beings stand to others. In a world where all aspects of the story are tightly interconnected and bending towards the broader arc of the plot, it can be virtually impossible to actually grasp this intrinsic value beyond the story of the game nominally inviting us to do so; in the Remake of this world, however, we have no choice but to acknowledge it: by committing to the true freedom of Cloud, his friends, and even Sephiroth, we jettison, as players, our capacity to know or even plausibly project what the world or its constituents can do next. No matter what actually happens to transpire in the inevitable follow-up to this game, Final Fantasy VII Remake itself concludes with characters for which any number of follow-ups are possible.

As players, all we can do is appreciate this universe as a plurality of beings that have transcended the concept of story—and bask in the awe that, as players, we have brought about a world that genuinely reaches beyond the fiction that brought it about in the first place.

- Thanks to Adam Bierstedt, Dan Hughes, and Shannon Diesch for input on earlier formulations of the ideas presented in this article. ↑

- As an upfront point of clarification, I am not arguing that any of this analysis is literally, as a matter of biographical fact, what the developers of the game intended to express with it: as in the majority of my work, I am arguing that this analysis is an illuminating and well-supported of understanding the overall set of data presented by the “text” that is the video game as an artwork unto itself. See my conversation with Caymus Ducharme in the comments section of my article on metaphysical vampirism in Code Vein for further background. ↑

- In a stroke of cosmic irony, I mentioned in that first article that I published it shortly after the announcement that Cloud was joining Super Smash Bros.; it’s only fitting, then, that this current article is published shortly after the announcement that Sephiroth was joining Super Smash Bros. ↑

- The exact manner in which a game’s events depend on the player is complicated and beyond the scope of this article, but you can find my preferred analysis of how this works in my “The Role of the Player in Video-Game Fictions.” ↑

- I previously conducted a comparative analysis of Six Characters in Search of an Author and The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask in an effort to explore the similarities and differences between the modes of role-playing present in each work. ↑

- See Mieke Bal’s Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative (1985), p. 113. ↑

- One might object that this whole exercise is pointless because, within the context of the fictional world represented by their stories, many characters are free. For example, the character of Tom Sawyer may have been created by Mark Twain, but within the context of Tom Sawyer’s fictional world, readers are meant to conceive of Tom simply as a regular boy who’s perfectly capable of acting freely for his own reasons. This objection confuses the level on which we’re analyzing characters: when we imagine characters as part of their fictional worlds, unless we’re told otherwise, we imagine those characters not as characters, but rather as people, exactly as the example of Tom Sawyer shows. On the other hand, when we’re considering characters as characters, that analytical perspective presupposes that we are viewing them as the semantic creations of authors who are using them as a storytelling element. This objection therefore misses the point of the question because we are considering what it means characters qua characters to be free. ↑

- I say “authorial entity” because this doesn’t need to be a case of believing that one knows what the literal author, as a biographical matter, happened to be trying to express through her story: this requirement applies equally, if not more so, to the “authorial entity” that Wayne C. Booth calls the “implied author,” the conceptual entity that the reader of a text infers, representing what kind of author—according to the substance of the text, and nothing else—could be said to have created the text in the way that it exists in order to express certain kinds of narrative meaning. That implied author may or may not resemble the literal, flesh-and-blood author of the text and that author’s fact-of-the-matter reasons for architecting the text in the way that she did. (See Wayne C. Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction for more on the concept of the implied author.) ↑

- This also, in my view, makes the rampant speculation about which characters the Whispers are meant to represent all the sillier. The Whispers could easily have been shown to be literal versions of characters like Tifa or Loz; that they are almost entirely nondescript, together with their thematic consonance relative to the themes I’m articulating here, makes me feel as though analysts miss the point when they try to ascribe particular identities to them. ↑

- Just as I did in my first article about the Whispers, I’m stipulating a player of Final Fantasy VII Remake who has previously played Final Fantasy VII and has broader familiarity with the Final Fantasy VII literature. The experience of a Remake player who lacks this context will of course be different. Anecdotally, though, I’ll offer one datum here that only reinforces my point in the main text. I played Remake for the first time with my partner who had never played Final Fantasy VII before, and one of the only things I felt obligated to explain to her as “background knowledge” in order for her to understand Remake was information about Sephiroth’s status as the archvillain of the series. In my view, this only underscores my argument that the Whispers (and, by extension, the narrative of Remake as a whole) preys on players’ preconceptions of who and what Sephiroth is. ↑

- Thanks to Adam Bierstedt for underscoring the implications of the Whisper-based Sephiroth defeat for the identity of Sephiroth in Remake. ↑

- The reader might object that despite this confrontation with Sephiroth, Cloud and the gang seem fairly sure that he is the ultimate enemy when they plan their next moves in the final scene of the game, outside of Midgar. However, a close reading of this scene suggests otherwise: outside of Midgar, the party finds themselves unclear as to what their next moves ought to be (Tifa directly asks, “So… What now?”). Cloud is the one to bring up Sephiroth, and he does so in a telling way: watching a black feather, symbolizing Sephiroth, dissolve in his hand, he remarks, “Sephiroth… As long as he’s still out there, I…” Cloud, who has been the player’s direct mode of engagement with Sephiroth throughout the story of Final Fantasy VII Remake, is here intimating that Sephiroth will still obtain in the ongoing plot of the story, yet the narrative valence of Sephiroth appears unclear even to Cloud: it’s not as if Cloud identifies him as a craven villain who must be stopped, and the subsequent remarks about stopping Sephiroth, offered by Aerith and Barret, seem to be merely filling in the blanks in a way that seems reasonable but doesn’t have significant backing in the overall context of Remake’s story at this point. (Thanks to Adam Bierstedt for pushing me on this.) ↑

- Thanks to Dan Hughes for this observation. ↑

- Thanks to Adam Bierstedt for raising this challenge. ↑

Continue Reading

- The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake series navigation: < “Solving the Puzzle of Roche in Final Fantasy VII Remake” | “The Drawing Board: The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake, Article Postmortem #2″ >

- Read more Critical Reviews

6 Comments

Borivoje Kostic · December 30, 2020 at 12:37 am

Just wanted to say that this may be the best article i have ever seen written for a Game. So much love and detail

Aaron Suduiko · December 30, 2020 at 2:32 am

Thank you so much for your kind words, Borivoje! In my opinion, the best analyses about video games help us better understand why we love them so much; it was a labor of love, so I’m glad that came through!

I hope you get the chance to check out the other articles in this series and the many other works our fine analysts have written about a wide range of games. Don’t be a stranger!

Subpar · December 30, 2020 at 1:40 am

I’m absolutely in awe of what this game accomplished. When FF7-R was in development I was terrified of potential changes damaging my feelings of the original story, but by going in such a bold direction and ending on a cliffhanger, it’s actually made me realize part of what made the first game so special, and I immediately found myself back on internet forums digging through interviews and synopsies to theorycraft what could be coming next, just like I did as a child when I played the original. Thats the strongest feeling of nostalgia that I could have ever asked for.

By completely breaking the boundaries on what it means to be a “remake”, FFVII-R has changed storytelling forever. We’re already seeing other franchises in other mediums adopting the “sequel disguised as a remake” formula. Thats a real advancement and argument for video games as a medium that matters. It’s almost frustrating as so many video game publications have shafted an actual revolutionary title that demonstrates the power of video games as a unique medium of art like FFVII-R, while simultaneously putting games like The Lastof Us 2 on a pedestal for poorly imitating film in order to feel like a “big boy” story.

Aaron Suduiko · December 30, 2020 at 2:37 am

I’ll admit that I do have a soft spot for The Last of Us Part II, but I couldn’t have expressed my feelings about FFVIIR better myself! It’s that belief in its genuinely groundbreaking storytelling potential that forms the mission statement at the heart of this whole series.

It’s a sad state when publications overlook such revolutionary material, but know that the one and only thing we do here at With a Terrible Fate is take video-games seriously as storytelling innovations and strive to better understand what makes them so special. Thanks for reading! Hope you keep in touch.

Peter Sanders · December 31, 2020 at 4:49 pm

Thank you for the excellent analysis! I have played through the game twice already, and after reading your article, felt the need to immediately go back and play the Destiny’s Crossroads chapter again. Playing it with the lens provided here was an incredible experience!

Aaron Suduiko · December 31, 2020 at 5:04 pm

Thank you for your kind words, Peter — I’m delighted that you enjoyed reading it and that it inspired you to play the game from a new perspective (that’s basically the ultimate goal of all the work we do at With a Terrible Fate!). I hope you check out some of the team’s other work when you’re able, too. Happy gaming!