Compelling science fiction uses the fantastical to represent the deeply personal, and nothing is more personal than the need to be seen.[1]

(Complete spoilers for Scarlet Nexus follow, along with very minor spoilers for The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Final Fantasy IX, NieR: Gestalt/Replicant, Silent Hill 2, Kingdom Hearts II, and Final Fantasy XIII-2.)

Stories that submerge you in complex science-fiction worlds or metafictional content are a gamble: like an ornate, 400-part Swiss watch, a perfectly orchestrated science-fiction or metafictional story can leverage every one of its parts to give us a unique, aesthetically meaningful perspective on the human experience that we couldn’t find anywhere else—but only if the pieces fit together perfectly.

In this analysis, I want to show you that Scarlet Nexus is a beautiful timepiece that functions flawlessly. Its intricate story represents something subtle, tragic, and deeply relatable: the pain of becoming obsessed with fixing a senseless accident that remains unfairly outside of one’s control no matter how much one tries to make things otherwise.

We’re going to focus on reading Scarlet Nexus as a meditation on the pathos of its main “villain,” Karen Travers: I’m going to show you that Karen is a tragic character because his “villainy” comes from seeking agency in a world that has the means to furnish him with it yet denies him, regardless of the worthiness of his cause. We’ll see that the science-fiction and metafictional elements of the game turn Karen’s fate into a uniquely moving and human story about the power of being seen—and how deeply one can be wounded when denied that opportunity.

My analysis proceeds in two parts. First, I motivate the view of Scarlet Nexus as a fiction whose ontology motivates the value of being seen; I do this by analyzing the origin and functionality of the Red Strings and Design Children, both within the context of the fiction’s plot and in the structural, metaphorical context of how players and avatars engage with video-game fictions more broadly. Through this analysis, we’ll see that the world of Scarlet Nexus is one that imbues the player’s attention with special meaning and power; this will put us in a position, second, to analyze Karen as a tragic figure who is denied that attention: one who deserves to be seen, yet cannot be. Ultimately, we’ll come to see Karen as the natural terminus of video-game storytelling’s genre of antagonists who recognize and rail against their limited agency in worlds governed by avatars and players.

(A special, heartfelt thank-you to Bandai Namco for providing With a Terrible Fate with a download code for Scarlet Nexus, which made this analysis possible.[2])

The Value of Attention and Being Seen in Scarlet Nexus

My claim is that Karen Travers’ pathos comes from deserving to be seen, yet not being seen, in a world where agency is derived from the player’s attention. Before we can understand the tragedy of Karen’s circumstances, we first need to understand what about Scarlet Nexus’ world grounds this particular relationship between attention and agency.

In order to explain this ground, I’m going to provide an ontology of the Red Strings, the time-travel psychic ability that weaves the main threads of Scarlet Nexus’ story together. In the course of providing this ontology, my claim will be that the Red Strings are a metaphor for the attention paid by the player of a video-game story to that story.

A note on method: by making an argument about the symbolic meaning of the Red Strings, I’m doing two things: first, I’m establishing the facts of what the Red Strings, Design Children, and related concepts actually are on the level of the game’s plot; second, I’m inferring how they relate to a more general understanding of player and avatar engagement in video-game stories, allowing us to set up a textually motivated analogy that imbues Scarlet Nexus with a particular kind of metaphorical content. That’s not to say that the metaphorical content is something that the literal creators of the game explicitly intended to imbue it with, but that’s also not to say that this method of theory-building is mere “speculation”: the virtue of this inferred symbolic content is that it’s motivated by a cohesive understanding of the story’s content, meaning that we can treat it as a sound way of interpreting the material in the game rather than extrapolating beyond that material.[3]

We’ll build up this groundwork in four steps:

- The motivation for the Red Strings

- The nature of Design Children

- The nature of the Red Strings

- The subordination of the rest of Scarlet Nexus to the Red Strings and its wielder

Design Children, Avatars, and Agency

The story of creating the Red Strings is that of creating an avatar.

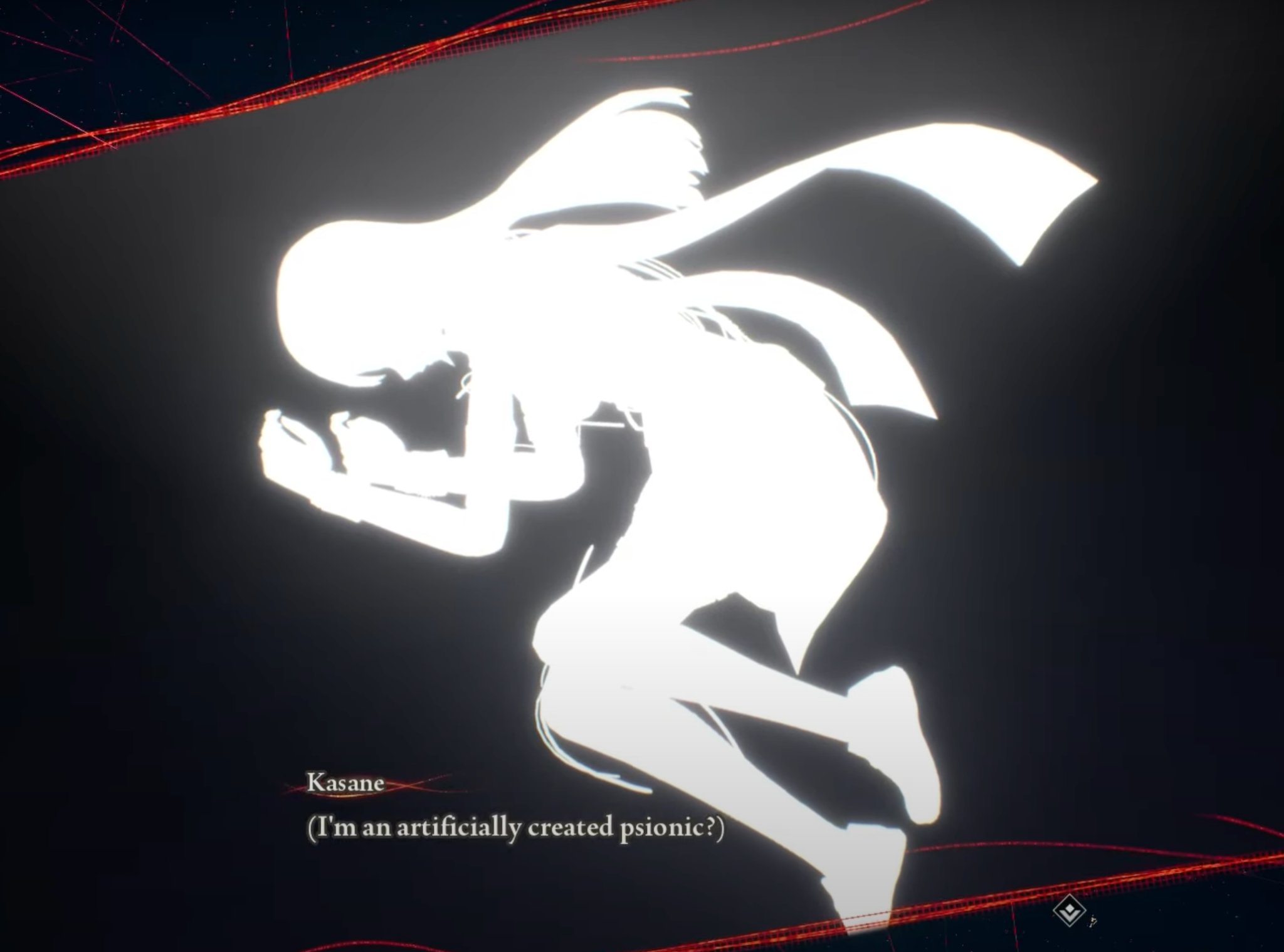

The combination of Yuito and Kasane’s journeys to Togetsu reveal Kasane’s origins as a Design Child: 3,000 years before the start of Scarlet Nexus’ story, a shift in the earth’s orbit ruined its climate, forcing humans to flee to the moon; after 1,000 years of climate rehabilitation, the moon sent a group of colonizers, including leader Yakumo Sumeragi, back to the earth to found New Himuka (and to mitigate lunar overpopulation); thereafter, Other Particles began appearing on the moon and transforming lifeforms into Others, leading society on the moon to push the Other Particles into the space between the earth and the moon that would become the Extinction Belt, isolating the earth and moon from each other. The sovereign religious nation-state Togetsu sought to “return” to the moon in the only way it thought possible: manipulating time in order to undo Yakumo Sumeragi & co.’s emigration from the moon.

Togetsu’s Design Children were those artificial lifeforms it engineered with the goal of creating an individual with the theorized Red Strings psychic ability, the capacity to traverse and alter timelines. This ability is a fully realized form of gravikinesis, the power to mentally manipulate gravitational fields (also described by Year-2070 Yuito as “the power to create dimensions”). Kasane was the successful Design Child who managed to cultivate the Red Strings ability—an ability that we learn is governed by its user’s emotions, as articulated by Yuito in an apocalyptic Year 2070 and elaborated upon by Arashi in the present-day 2020 thereafter:

The time travel power, the Red Strings, is affected by Kasane’s strong emotions. When something shocking occurs, her emotions must be stored as a kind of energy. Since Kasane is unable to control her time travel power, it activates immediately. I was worried there was a danger she could become lost in time and unable to return to the present. However, that doesn’t seem to be the case. There must be some kind of guide when Kasane makes a jump. She must be attracted to time periods she has already experienced or is familiar with. And Kasane sees that guide as red strings.

While it’s not made explicit over the course of the story, the “guide” to which Arashi refers, anchoring Kasane’s jumps through time, seems to be Yuito. The moments in the future and past to which Kasane travels focus on moments in Yuito’s history (his separation from his mother; his final moments in a cataclysm he brought about) rather than Kasane’s; in this way, he acts as a “beacon” tethering Kasane’s travel, as he describes himself ahead of her jump to the past to find their mother, Wakana.

The story of the Red-Strings-bearing Design Child, then, is one of an artificial human being created in order to resolve an unexpected outcome from an inexplicable force that turns people into unrecognizable, antagonistic creatures (nearly) robbed of their sentience—an artificial human being who can resolve this outcome through spacetime jumps that are fueled and governed by emotional salience, tethered to a relationship that being has with someone else.

With this reconstruction of the meaning of the Red Strings and Design Children within the plot on the table, we’re now in a position to understand the symbolic relationship that these elements bear to avatars, players, and agency within a video-game fiction. In order to articulate this symbolism, let’s take a step back from Scarlet Nexus for a moment and reflect on the structure of video-game stories more generically.

Like a Red-Strings-bearing Design Child, an avatar is an artificial being designed with certain abilities in order to serve a certain function within a story: namely, an avatar provides a point of view and conduit through which the player can make sense of events within a story and exert her agency to advance those events to an emotionally meaningful conclusion. Without a unifying point of view, the antagonistic elements within a work of fiction are as illogical as Other Particles turning characters into monsters: the concept of antagonism in the absence of a coherent protagonistic perspective is chaotic at best and incoherent at worst, lacking the holistic meaning that comes from a well-constructed story’s plot. Like the Red Strings, an avatar’s unique ability within a video-game story is the power to navigate the world through spatiotemporal means unavailable to other characters, whether that’s quasi-teleportation (commonly known as “fast travel”), small jumps backward in time (returning to earlier “save points” after the avatar is killed in battle), or huge jumps to alternative timelines (“New Game Plus” mechanics).[4]

Yet, also like the Red Strings, this ability of the avatar isn’t boundless: the bearer of the Red Strings depends on emotional fluctuations and the “beacon” of another character that’s relevant to them in order to use that power; similarly, an avatar’s capacity to navigate the world in which it’s embedded is governed and limited by the story in which it is embedded, through which it must navigate. Its progress through that story, like the Design Child’s travels with the Red Strings, is typically informed by (1) the avatar’s relationships with other characters, which motivate the avatar’s decisions and thereby inform the choices available to the avatar (and, by extension, the player) in its travels, and (2) the emotional content of those choices, insofar as the overall arc of a story is organized in such a way as to create a certain emotional cadence for the characters and audience.[5] And, in both cases, the agency of the spacetime-manipulating entity in question is derived from and dependent upon an observing entity engaging with the avatar’s world from outside of that world.

While the avatar of a video game has unique ontological qualities based on its relationship to point of view and ability to determine events through its actions, these qualities are ultimately in service of the player’s engagement with that story: as the audience of the story, the player is the one for whom the emotional cadence of the story is architected, and the one for whose access the point of view was designed. She is the one who experiences the real impact of the story being told, and she is also the one choosing how to advance it based on the actions available to her, most of which consist in making it the case that the avatar acts in various ways.[6] Seen through this lens, the player’s attention—the focus directed toward understanding and deriving a story’s meaning from particular fictional content within that story—can be seen as the ultimate energy advancing the story of the game that the player engages, for it is this attention that drives the player’s choices of what to do within that story, consequently determining the actions of the avatar.

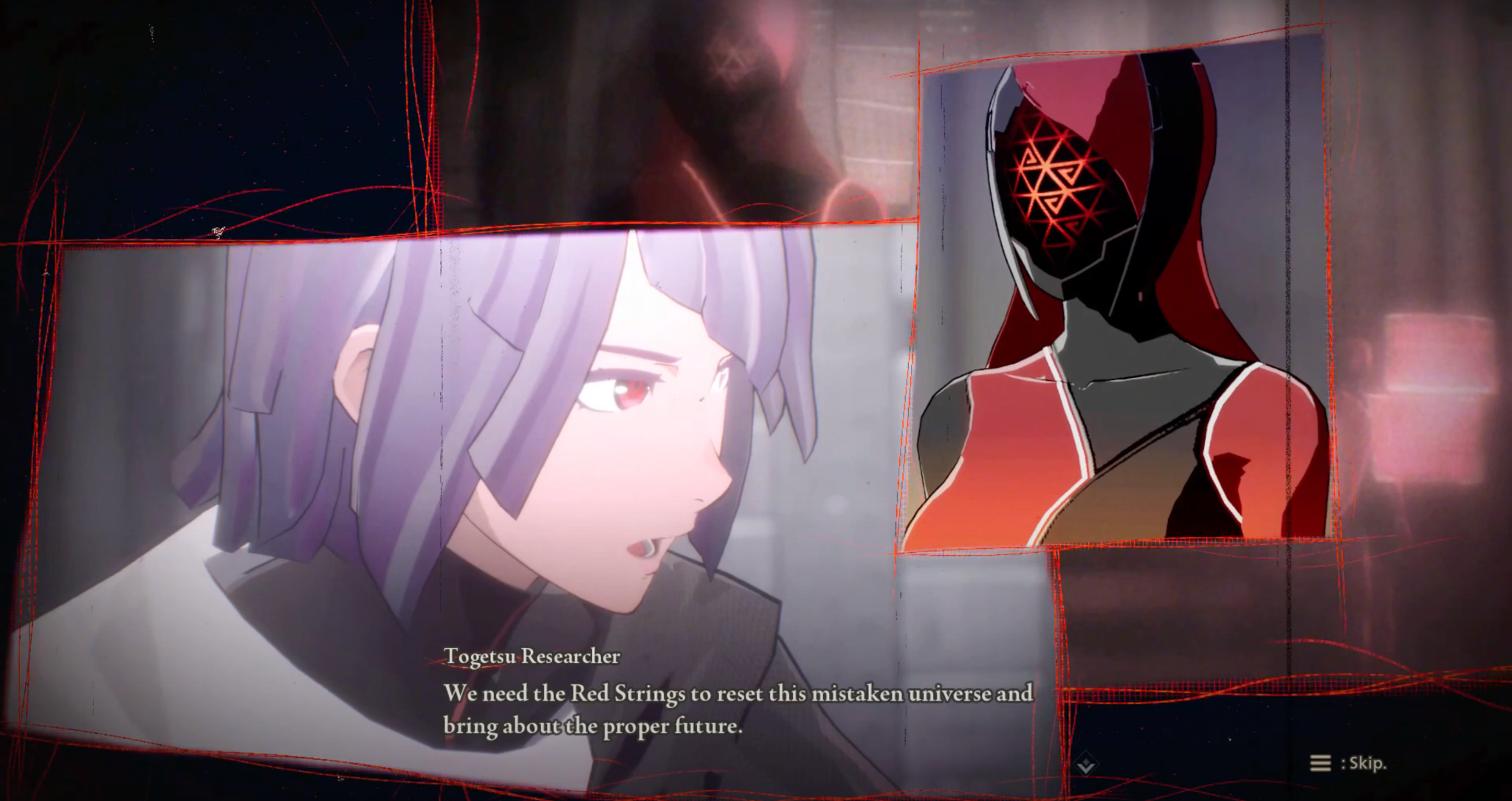

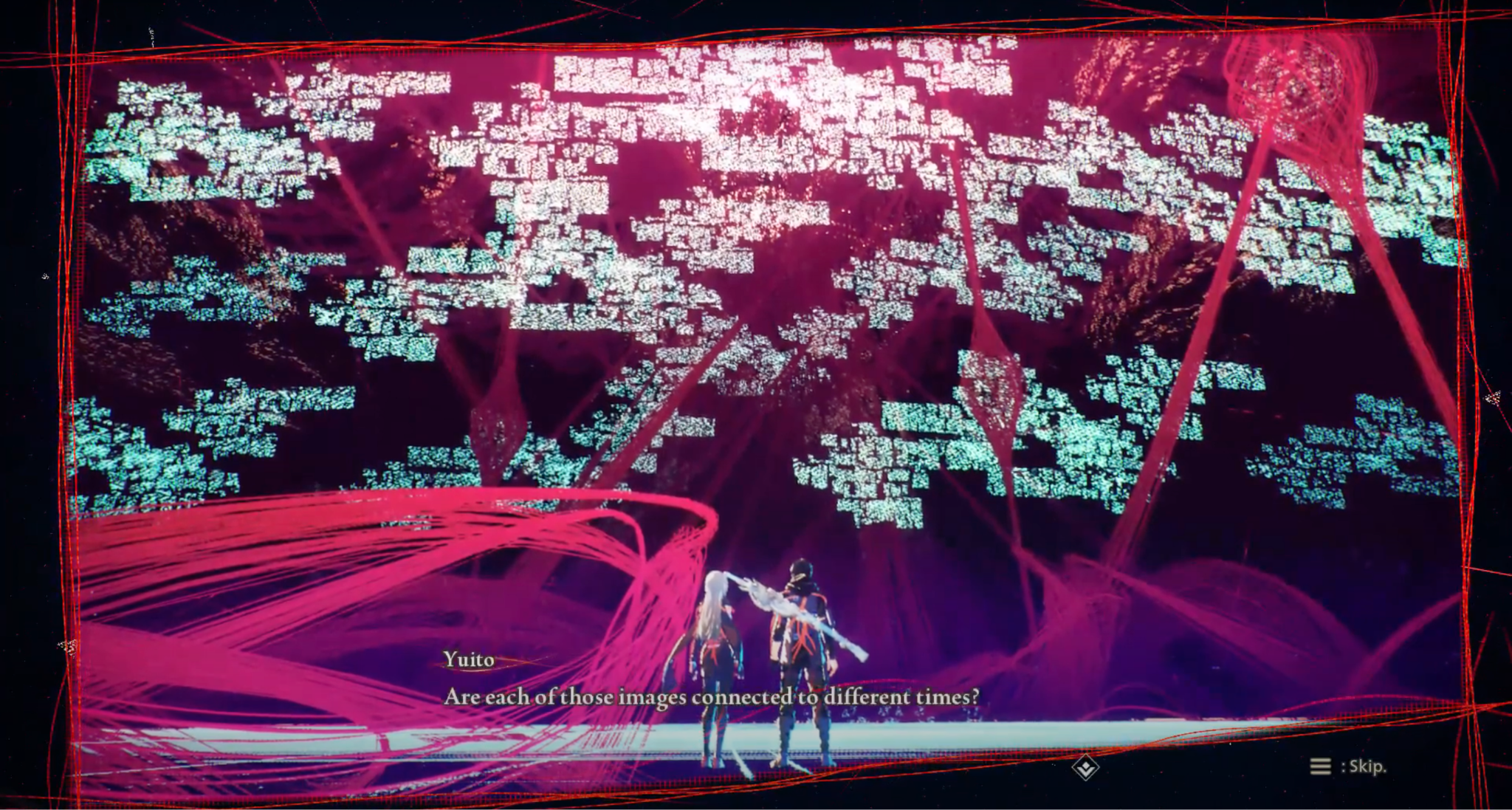

Scarlet Nexus’ story prioritizes the player’s attention in a structurally analogous way. The means through which Red-Strings users are able to navigate time is represented by an abstract space Togetsu called the Chronos Terminal: in Wakana’s words, “an imaginary world” that is “built from [the] consciousness” of the users, only perceptible to the users and physically affected by their emotions and relationships to history. This terminal models the users’ relationship to space and time through myriad images framed by red strings (depicted above), representing different moments from throughout their history. It’s salient, in this context, that the mode of presentation through which the player experiences the world of Scarlet Nexus is oftentimes just like the Chronos Terminal: a sequence of red-strings-bordered panels suspended in an abstract space, even with the objects later identified as spatiotemporal entanglements sometimes passing by in the background (depicted below).

A typical cutscene presentation in Scarlet Nexus. Notice the overlaid windows into various characters and moments of interactions, framed by red strings; notice also the shape in the bottom-right-hand corner, similar to the entanglements represented inside the Chronos Terminal in Phase 11.

We also see a flurry of interwoven footage from the “real world” (i.e. footage of real people rather than animated characters) when Kasane and Yuito first discover and activate their brain fields, physical extensions of their minds that can draw other entities into their mental influence by pushing their psychic abilities beyond their natural limits. While this footage is never discussed within the game, it stands out for the unexpected connection it draws between the game’s world and the real world.

An excerpt from Yuito’s experience of activating a brain field for the first time.

Yuito’s collapse of identity following Karen’s use of Arahabaki to steal his power also gradually erases both his experiences and his own name as he wanders the Chronos Terminal, lost; before his friends and his mother reconstitute him from their own memories and data from his earcuff, his name in the game’s subtitles is gradually reduced from ‘Yuito’ to ‘Yu’, a provocative suggestion that he has been erased of everything except for his relationship to the player directing him (“you,” the audience).

Yuito, his identity ground down to merely ‘Yu’ in the Chronos Terminal following Karen’s assault at Arahabaki.

This constellation of data—(1) the player’s perceptual relationship to the imagined world through which the avatars implement their abilities, (2) the avatars’ subliminal connection to the real world upon most fully actualizing their mental abilities, and (3) Yuito’s foundational connection to the player’s agency—suggests that, like an avatar beholden to the attention and directives of a player, the Red-Strings-bearing agents in the world of Scarlet Nexus are able to realize and implement their abilities through the attention of the player, who engages with their world through their perspective and chooses to use their abilities according to what in the story is meaningful to them.

That isn’t to say that the player is a literal character within the fiction of Scarlet Nexus, manipulating the minds of Kasane and Yuito. Rather, this is taking the observation that the Red Strings empower their user to manipulate space and time in a way that is organized around emotional experience rather than ordinary causal logic and arguing that the game’s fiction supports interpreting the person who is experiencing the story’s emotional content (i.e. the player) as the explanatory force that makes this non-causal navigation of the world possible within the fiction’s world. Just as the player of a generic video game is able to empower and direct the avatar’s unique agency by virtue of her attention, so is the player of Scarlet Nexus able to empower and direct the users of the Red Strings by virtue of the attention she pays to the world and its characters. In this context, it is reasonable to identify the player’s role with the power of the Red Strings itself: she and her attention are precisely what enable Kasane and Yuito to navigate the spacetime of their world in an emotionally charged way unavailable to others. The consequence is that the story and world of Scarlet Nexus ultimately depend on the player’s attention for their value; and, since Kasane is the Design Child in whom the Red Strings initially developed and it’s through her perspective that players access and engage the world, we find that the other characters—and, indeed, the rest of the world—are therefore at the mercy of their relationship to her for their value.

The Consequences of Subordinating Scarlet Nexus’ World to Kasane

To show us the pathos of a villain who deserves the player’s attention yet is denied it, Scarlet Nexus carefully illustrates the extent to which every entity in its world depends on Kasane, the Design Child bearing the power of the player’s attention, for its value. It shows the full range of the kinds of value that can be conveyed through this attention, from the good, to the bad, to the paradoxical. To understand the character of Karen Travers, we’ll explore case studies of the player and Kasane’s impact on entities that fall into each of these three categories:

- The good: Kasane and the player’s capacity to bond with and empower other party members

- The bad: the subordination of society’s total consciousness to Kasane and the player’s abilities

- The paradoxical: the untenable elevation of Yuito to the position of avatar by virtue of Kasane and the player’s intervention

In line with our metaphorical reading of the story, these three categories correspond to the avatar’s influence on party members, NPCs, and its closest relationship with another character, respectively. Once we examine each of these in turn, we’ll understand how the entirety of Scarlet Nexus’ world bends to the authority of the player and Kasane’s attention, making Karen’s plight significantly more intelligible in the process.[7]

Making Connections through Attention

Hidden in the mechanics of Scarlet Nexus’ bonding system is a subtle way of showing how Kasane, Yuito, and the player’s attention can strengthen those they cares about by strengthening their relationships with them.

In the final Bond Episode between Kasane and Arashi, in which Arashi acknowledges that Kasane has changed her mind about the value of sentimental keepsakes (presumably also changing her perspective on her relationship with her brother, Fubuki, in the process).

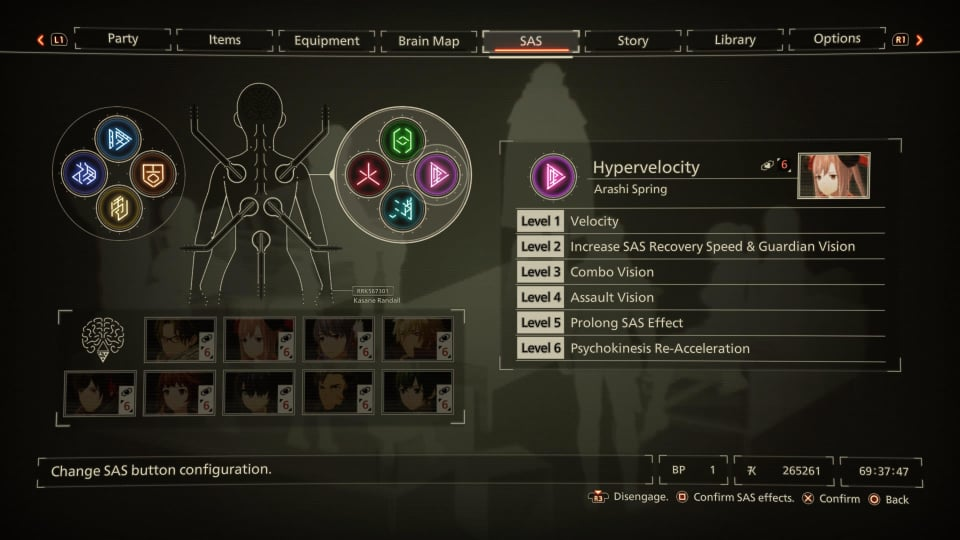

Kasane and Yuito are able to develop their connections with their nine eventual teammates (including each other) through Bond Episodes, one-on-one interactions in which they gradually comes to know everyone better and vice versa, developing mere acquaintances into close confidants. Between these episodes and giving their allies gifts that they find uniquely meaningful, Kasane and Yuito are able to team up with them in new ways out in the field, getting new combat abilities and being able to literally connect their minds for longer, more robustly.

A representation of the improvements available to Kasane and Arashi’s combat relationship through SAS; these unlock as their relationship deepens through Bond Episodes and gift-giving.

These relationship-building mechanics simultaneously make the bonds between Kasane, Yuito, and their friends narratively meaningful and reinforce the avatars’ status as the nexus of those relationships. The SAS—or struggle arms system, which allows the minds of psychic individuals to link together, ostensibly administered by the Arahabaki mainframe that underpins New Himuka psionic technology—provides a narrative explanation for how Kasane and Yuito’s time spent with allies makes them stronger together: because Kasane and Yuito’s minds are linked to those of her companions, they can better coordinate and synergize their actions as they come to better understand each other, as they do through Bond Episodes and knowing enough about each other to give meaningful gifts. Yet notice that in a given playthrough, the avatar is the only member of the group with the ability to cultivate and strengthen bonds in this way: there’s no mechanism, for instance, for Arashi and Luka to spend one-on-one time together and utilize each other’s abilities more effectively, even though they’re connected each other through to the same SAS matrix that connects them both to Kasane and Yuito.

This reinforces the value that the player’s attention can impart to characters within the world of Scarlet Nexus. We’ve established that Kasane and Yuito’s unique abilities to traverse space and time are grounded in their connection to the player’s attention; now we see that, by virtue of connection, Kasane, Yuito, and the player’s choice to focus attention on characters close to Kasane and Yuito allows those characters to more deeply know Kasane and Yuito and thereby be able to further participate in Kasane and Yuito’s unique powers, making Kasane and Yuito’s companions more relevant and capable within the story in proportion to the amount the player focuses on them. Inversely, if players find these Bond Episodes tedious and don’t bother to engage with getting to know Kasane and Yuito’s companions, then those companions’ stories factor less into the overall story and they are correspondingly less capable in the party’s adventures.[8]

This structure of developing not only the avatar but also the player’s relationship with supporting characters manages to achieve something unusual: an interested player can come to have a rich understanding of ten different characters—a marked increase from the six or eight typical of JRPGs, especially Bandai Namco’s—by the time she’s completed Kasane and Yuito’s stories.[9] This makes the celebratory, final Team Bonding episode (shown above), bringing all ten party members together after Kasane or Yuito has gotten to know every one of them very well, all the more gratifying. Yet we only know these characters so well in relation to Kasane and Yuito: we know, for instance, that Kagero and Tsugumi are friends, but we aren’t privy to what that friendship looks like “from the inside.” Like the powers Kasane and Yuito’s friends can develop, the player’s understanding of these characters, the focus of her attention, is entirely relational to Kasane and Yuito, our point of view and window into the world of Scarlet Nexus: we don’t know these characters per se so much as we know how they relate to the avatars, and thus their relevance, while material and fulfilling, is subordinate to the avatars’.[10]

Though party members’ places in the story are subordinate to the avatar, this still affords them with the potential for an entirely fulfilling story: by virtue of being connected to Kasane and Yuito, they can draw the player’s attention, and this means that a player who is sufficiently interested can spend the time to engage with all Bond Episodes, giving these characters the equivalent of complete, emotionally satisfying “short stories” to Scarlet Nexus’ novel. The same, tellingly, cannot be said for the much broader swath of society with which Kasane and Yuito lack direct, intimate connection.

The Perils of Disconnection

The ultimate impact of two supercomputers unifying countless minds is the illustration that those minds are at the mercy of Red-Strings users.

Interwoven with Scarlet Nexus’ tales of interpersonal, geopolitical, and existential conflicts is a tale of two “bio computer[s] comprised of brains”: Arahabaki, the computer that controls operations in New Himuka and is connected directly to the minds of its psionics, and BABE, the sentient computer that operates Togetsu, controlling its Design Children and architecting its plot to change history.[11], [12]

In terms of base functionality, these machines have antithetical purposes. In administering New Himuka, Arahabaki collects unfathomable amounts of data about humanity on Earth, running simulations (according to Karen) to better understand the world—this earning its Secure Site the appropriate title of “Humanity’s Wisdom” (shown above). Contrast this with BABE, which, rather than openly intaking and learning from external data about the world, has all of its operations and computational power focused on the singular task of erasing that world and changing history to undo the emigration from the moon, primarily by way of developing and taking advantage of someone with the Red Strings—in its view, securing the path to the “One and Only Future” (shown below).

Yet despite their antithetical purposes, these computers share a deep similarity: despite having access to, and being constituted by, a staggering amount of literal brainpower, they are subordinate to Kasane and Yuito. We see this most clearly in the anticlimactic confrontation between the party and BABE: despite being an artificial sentience with tremendous computational power and centuries of research on the Red Strings, BABE’s final move to seize the power it needs from Kasane and Yuito is to appeal to their emotions through the flaccid, almost comical ruse of projecting a vision of their mother, Wakana, and trying to emotionally motivate them to erase the emigration event in just the way that BABE wants.

Though it may seem comical, BABE’s method in this confrontation is illuminating evidence for the primacy of Red Strings, Design Children, and the player’s attention in the world of Scarlet Nexus:

- BABE begins by saying that it manifested the form of Wakana because it knows “she is important to both Yuito and Kasane” and therefore believed it “would be [the best way] to get [them] to listen.”

- BABE then tells them that “all of the people who are important to [them]” are at risk of being destroyed by the Kunad Gate, the anomaly caused by the temporal entanglements of Kasane, Yuito, and Karen, and that it needs their help in order to save them.

- Finally, BABE appeals to the most emotionally charged content to which it would have access about each of them: knowing that Wakana left Yuito alone when he was young, it promises that “[his] loneliness will be cured” if he helps it; knowing that its researchers tested Kasane’s powers by murdering a puppy she loved in order to elicit an emotional response, it warns Kasane that the death of everyone to the Kunad Gate would be just like the death of that puppy (pictured above).

Despite being able to complete complex computations and project its own data through time (by virtue of having assimilated Wakana’s brain), BABE recognizes that the very Red Strings it covets empower Kasane and Yuito to navigate the game’s world with an agency that it cannot impede; its only option, therefore, is to try to make its mission emotionally compelling to them—and, by extension, to the player—in order to intrinsically compel them to use the Red Strings in the way it desires. It does this by [1] putting its mission in the mouth of their mother, with whom they have an intimate, familial bond, [2] appealing generically to the idea of people whom they value (people like the other eight party members we discussed above, for instance) and who are at risk of suffering if its mission is not enacted, and [3] trying to trigger their emotional receptivity by calling to mind their previous emotional experiences.

Notice that the player’s experience of this confrontation with BABE is consistent with the unity between the player’s attention and the power of the Red Strings, as I argued above. The player, watching the hollow entreatments of the fake Wakana, probably won’t feel persuaded or interested at all, instead recognizing the speech of BABE’s Vision as an empty argument being made by a computer without the leverage to do anything else. This appeal, therefore, does nothing to stoke the player’s attention and interest in making the executing of BABE’s plan a part of Scarlet Nexus’ main plot, ontologically explaining the inability of BABE to take advantage of Kasane and Yuito’s abilities.

On the level of Scarlet Nexus’ symbolic content, this also extends the metaphor of the player and avatar’s power to the role of NPCs. We previously described avatars as the locus of point of view through which the player of a video game perceives its story; this gives players not only insight but also attachment to the avatar’s experiences, seeing them as the main events that make narrative meaning out of their actions upon the game. In comparison to events in the avatar’s life that the player’s actions make possible, the lives and plights of NPCs can oftentimes feel hollow to players. Picture the generic NPC standing in the middle of a JRPG town, inviting the avatar to listen to his plight and help him with some problem in an ensuing sidequest: one of the foundational reasons that it’s so much harder for a player to emotionally invest in such an NPC’s history than in an avatar’s is that the events in the NPC’s history are conveyed descriptively, whereas the avatar’s are conveyed experientially: we are simply told about things that have happened to the NPC in its life, whereas we experience the events in the avatar’s life along with it—and we are oftentimes responsible for bringing those events about. BABE shows the gulf between these two types of narrative content exaggerated to the extreme: computerized brains with no concept of experience, only able to engage with or deploy descriptive content, are persuasively inert in the face experientially-driven players and avatars who have already been through tens of hours of plot together.

This mode of NPC subordination is mirrored, albeit more subtly, in Arahabaki. Rather than a sentience that wants something it cannot possibly motivate, as we saw in BABE, Arahabaki is essentially a superpowered terminal for using the majority of all NPCs in the world as a tool for one’s own ends. As Luka says (pictured above), the administrative mainframe for New Himuka “can forcibly access and broadcast to all citizens at once” (presumably with the exception of duds, people without psychic abilities). Over the course of the game, we see Yuito and his platoon use Arahabaki to expose Kaito’s plan to use the citizens of Suoh as pawns to go to war with the moon, “forcibly” uploading a covert recording of him to all of their minds; in that recorded conversation between Kaito and Yuito, Kaito expresses a plan for Yuito to connect to tens of thousands of ordinary citizens using SAS in order to move the Extinction Belt, a move that would kill those citizens and presumably use Arahabaki to facilitate the mass SAS connection; in the game’s finale, Kasane, Yuito, and Karen use the power of Arahabaki to actually move the Extinction Belt, drawing power from other psionics and the brainpower of the supercomputer in the process; Karen, too, connects to Arahabaki after traveling to the past, using its connectivity to the minds of humanity to accumulate data and run simulations for his own ends.[13]

One can imagine a story in which the aggregation of NPCs’ wills is used at the NPCs’ discretion to empower the avatar (e.g., Okami’s finale), in which case the NPCs find themselves in a position of agency and self-empowerment despite their distance from the player. Arahabaki shows us the dark reflection of this: a way in which the avatars can “empower” themselves by taking advantage of countless other minds that lack the agency to say otherwise.

Once we’ve understood Kasane and Yuito to be the center of Scarlet Nexus’ story and universe, advancing its plot through their emotional content that directs the player’s attention, we can understand the extent to which other characters are privileged in the plot by virtue of the degree to which the avatars personally care about those characters and the degree to which the player, correspondingly, attends to those characters. Our study of the other party members showed us that those close to the avatars can be empowered and elevated in the plot; our study of BABE and Arahabaki has shown us that those beyond the realm of the avatar’s personal interest are at the avatar and player’s mercy, used in the plot without being integrated into it.

The Paradox of Multiple Avatars

Things get more confusing when we look more closely at the avatars themselves.

So far in this section, we’ve been treating Kasane and Yuito as two entities on a par with each other, both having priority over the other entities in the world of Scarlet Nexus—but remember, we discussed earlier the fact that Yuito functions as a kind of “beacon” for Kasane’s use of the Red Strings. Now, we’re in a position to expand that observation and see that, as their disparate heights on the game’s title screen suggest, Kasane actually has ontological priority over Yuito and functions as the “true avatar” of Scarlet Nexus.

Remember that the metaphorical link we established earlier between the nature of avatars and the nature of a Red-Strings-bearing Design Child applies specifically to Kasane’s particular origins and abilities; while Yuito can also be used as an avatar with his own path through Scarlet Nexus’ story, the closer one looks at him, the more he appears to be a kind of artificial or “false” avatar whose abilities are parasitic on Kasane’s inherent and authentic abilities.[14] Once we understand exactly how this is the case, we’ll come to see Yuito as a compelling and unusual meditation on the paradoxical nature of a video game’s main character fully investing in another character.

BABE (through Wakana) and an older Yuito (in the year 2070) both identify the unexpected resonance of Yuito with Kasane’s Red Strings as the cause of the Kunad Gate, the pseudo-black hole that threatens to swallow all of time and space after the death of Seto triggers Kasane’s power. And indeed, as Yuito’s history is unfurled across the course of the game, it becomes clear exactly how and why the very nature of his existence is fraught with contradiction.

- We learn that Yuito was born a dud, lacking psychic abilities until Kasane and the player used the Red Strings to travel back to his childhood to bring their mother to the future in an effort to undo the Kunad Gate; during this episode, it’s implied (shown above) that Kasane intuitively shared her own power with Yuito when saving him from an Other attack, giving him a kind of artificial access to gravikinesis. This explains why his Red Strings power isn’t robust enough to fully traverse time as Kasane does, as well as why we see him gradually lose control of its power as it degrades over the course of the game—a loss of power that, true to our analysis of the Red Stings as the player’s attention and agency, is represented by the player literally losing the ability to control Yuito during his breakdowns.

- We learn in the game’s conclusion that Yuito’s entire lineage originates from a spacetime entanglement since Karen traveled back in time, killed Yakumo Sumeragi, and took his place, making Yuito the heir to an altered and causally incoherent history.

- By the end of the game, Yuito is even more artificial than Kasane in the sense that, following Karen’s fracturing of his identity at the Arahabaki Secure Site, his entire sense of self had to be reconstituted using data from his friends’ memories of him and his personal history stored on his ear cuff.

Taking all of these challenges of his identity together, we arrive at the view that Yuito is a character not fundamentally meant to be an avatar, who had the agency of an avatar artificially thrust upon him by the attention paid to him by the actual avatar, Kasane. It’s in this sense that Yuito is a “false” avatar whereas Kasane is the “true” avatar of Scarlet Nexus: the Red Strings that effect the spatiotemporal agency unique to an avatar are native to Kasane, whereas they are only artificially imposed on Yuito by Kasane, meaning that he is ontologically subordinate to her. Understanding Yuito and Kasane as these two foundationally different kinds of avatar illuminates how Yuito’s many paradoxes complete our image of the total primacy of the player and Kasane’s attention in the world of Scarlet Nexus.

Yuito’s particular type of paradox within Scarlet Nexus’ plot might initially seem esoteric, but I think his character has surprisingly broad applicability in the realm of video-game storytelling. Remember that, in our preliminaries, we identified Yuito as the “beacon” whose relationship to the avatar, Kasane, defines the limitations of her capacity to use the Red Strings, thereby shaping the trajectory of the overall plot as represented by her jumps through time. In stories generally (as in life), main characters typically find their actions motivated by their closest relationships—that’s part of what makes the logic of stories comprehensible. This structure, I think, is even more common in video games because the main character, the avatar, depends on the player to determine and effect many of its actions; for the player to do so in a way that’s consistent with the emotional arc of the game’s plot, the actions available to her ought to be guided by the avatar’s interest in another character, “tethering” them to the logic of the world as Yuito does Kasane. Thus we see:

- Zelda/Sheik motivating Link’s actions in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time

- Garnet motivating Zidane’s actions in Final Fantasy IX

- Yonah motivating the protagonist’s actions in NieR Gestalt and Replicant

- Mary motivating James’ actions in Silent Hill 2

The list could go on, but it should be sufficiently clear that this structure is common and transcends genre. The only limiting requirement I see is that the video game ought to have as a main focus a substantive and explicit plot such that this motivational structure can guide the avatar and player along it, and we see that borne out by games that lack this kind of plot as a focus: think of a game such as Skyrim, where an avatar that lacks this kind of motivational structure leads the player to focus more on boundless exploration of the world than on the game’s plot.[15]

While it’s not immediately obvious, there’s a tension in this structure that the relationship between Yuito and Kasane deftly captures: an avatar that is sufficiently invested in another character will want to give that character the same position of primacy and privilege within the plot that the avatar itself has, but the structure of video-game stories doesn’t allow that—and, as we see with Yuito, an attempt to overcome that limitation only riddles the story with intractable paradoxes.

The problem is a feature of video-game storytelling that I called event-relativity in my ontology of video-game stories (§2.2.3, “Characters,” pp. 28-33): this is the fact that “changing the perspective through which events are conveyed to the audience—i.e. changing the avatar—changes the fundamental events of the narrative.” Because the events of a game’s narrative are determined by the actions of its avatar and the reactions of NPCs, changing which character is the avatar changes the fundamental structure of the events constituting the game’s story. My favorite example illustrating event-relativity is the dissonance between Dishonored and its DLC from a violation of event-relativity: put simply, the main game and its DLC both purport to represent the same event in which Corvo (the main game’s avatar) confronts an assassin (Daud), but the fact that the event is represented by Corvo as the avatar in one case and the assassin as the avatar in the other case means that it cannot be the same event after all: based on which character has the agency, the factors that determine the dynamics and outcome of the confrontation are totally different in the main game and the DLC.[16]

An example of mutually exclusive and incompatible story events from Kasane (left) and Yuito’s (right) storylines: in the final confrontation, Karen grabs and attempts to steal the power of whichever one of them is serving as the avatar, with the other intervening and stopping him at the last moment (Yuito image flipped for effect).

We see discontinuities of this flavor in the two different paths through Scarlet Nexus. For instance, based on the player’s choice of avatar (Kasane or Yuito), Karen will confront and try to steal the powers of someone different at the end of the final battle—Kasane or Yuito, whoever the chosen avatar is—and the would-be avatar that the player did not choose will intervene and stop him (shown above). These discontinuities in the events within the plot in which Kasane and Yuito both participate illustrate the breakdown in logic that happens when the character that serves as the point of view determining factor in a plot’s progression attempts to share that role with someone else, regardless of how intuitive is is that a main character would want to grant that ability to their closest companion. Seen through this lens, it’s telling that in every example of avatar-character bonds I listed above, the plot avoids paradox and discontinuity by ironically disempowering the character that motivates the avatar: Sheik is captured by Ganondorf; Garnet is routinely crippled, withdrawn, and even rendered mute; Yonah is seized by the Shadowlord; Mary is captured by the mystery of Silent Hill and James’ own guilt-ridden psychology.

In a world governed by the player’s attention directed through a character that’s motivated by a relationship so fated as to be literally represented by Red Strings between their hands (shown earlier), it’s natural for the player’s attention and investment to extend to the other character in that relationship; the paradox of Yuito’s subordinate relationship to Kasane shows that this is untenable to the point of generating a spatiotemporal discontinuity powerful enough to consume the entire plot (the Kunad Gate). It’s especially interesting in light of this analysis that the resolution of Scarlet Nexus, following the unraveling of all temporal entanglement, sees Yuito accepting that his avatar-like powers will fade and aspiring to govern the earth—a position more aligned with the NPCs we’ve seen throughout the world, populating and governing its society—whereas Kasane intends to continue fighting Others on the moon—a path more aligned with the attributes of an avatar and the actions the player has been taking throughout the story so far.

The Nexus of Attention

We now have the full picture of Scarlet Nexus’ fictional ontology, which will allow us to understand just what makes Karen’s position as the antagonist so tragic. Let’s take stock.

The player engages with the game’s story through the point of view of an avatar—the Design Child, Kasane—who, by virtue of the player’s attention, which follows the content that is emotionally salient to that avatar, is able to traverse time and space in ways that give itself a priority unavailable to other entity. Those other entities only have agency and presence in the story to the extent that the player and avatar attends to them, and they benefit from that attention to the extent that the player and the avatar are invested in them: those with personal connections to the avatar, like party members, can become increasingly relevant in relation to the plot and the avatar, whereas NPCs, like those amalgamated by BABE and Akihabara, are more instrumental to the plot than intrinsically valuable entities in it. Yet those entities are always subordinate to the avatar and the player’s attention: those who get too close and try to participate in the avatar’s agency, like Yuito, create paradoxes in the plot and undermine their own essential nature.

It’s into this world that Karen Travers makes his plea, only to be met with cosmic indifference.

Karen Travers and the Agony of Video-Game Antagonism

To paraphrase the man himself, the tragedy of Karen Travers is that he has but one wish in the world, and it is denied to him.

Karen’s is an emotionally moving story that deserves satisfaction: he lost one of his few and closest friends, Alice Ichijo, to a senseless accident deeply related to the core issues of Scarlet Nexus’ world. Despite this, his distance from the attention of Kasane and the player leave him imprisoned in an apathetic universe where his only option to save Alice is to erase himself from the game’s plot completely.

To understand the pathos of Karen, we’ll explore his story in three steps:

- The content of Karen’s pain, and why it warrants Kasane and the player’s attention

- The plots Karen sets in motion in an attempt to ease his pain

- The final confrontation between Kasane & co. and Karen, and how Karen comes to remove himself from a world that doesn’t care for him

When we’re through, we’ll understand and appreciate the clockwork of Scarlet Nexus as a melancholy reflection on villains whose only sin is distance from the player’s agency.

The Lived Pain of Karen Travers and Alice Ichijo

Karen is the epitome of a well-intentioned outsider without the ability to will the change he desires in the world.

Karen Travers, Luka’s brother, was a dud (like Luka) who was given psychic powers artificially through experimentation. His power, “Brain Eater,” is the ability to copy and use the powers of other psionics, rather than any non-relational power intrinsic to him. Despite being singular in his intentions and convictions, Karen had two close friends from his childhood onward: Fubuki Spring and Alice Ichijo, the two of whom eventually become engaged to marry each other.[17] Karen’s power is renowned, his psychic and combat abilities are universally feared and respected, but he is always on the outside: outside of the kinds of powers other psionics have, outside of the romantic bond his two best friends shared; even those actions that seem to singularly belong to him in the plot, such as inciting Seian’s rebellion, are merely carried about by a different nameless rebel once he erases himself from history at the end of the game.

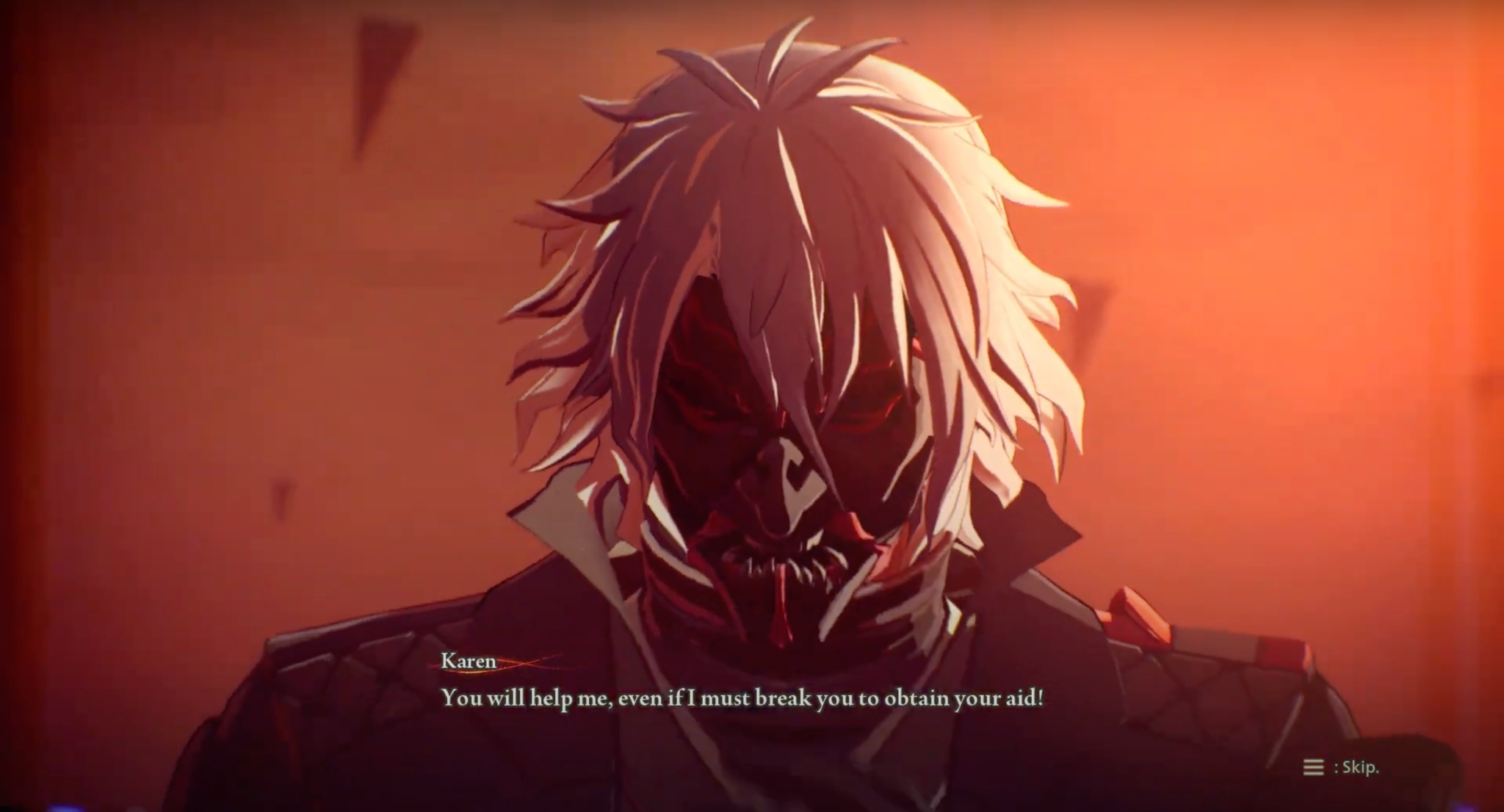

Karen’s inescapable pain comes from a selfless act that saved him from a senseless nightmare. When Karen, Fubuki, and Alice went patrolling, the Extinction Belt fell low to the level of the earth’s surface—an extremely rare event with no apparent logic to it. Seeing that Karen was about to be swept up in it, Alice pushed him out of the way, only to suffer the consequence of transforming into an Other from exposure to the Other Particles constituting the Extinction Belt (pictured above). Ever stoic, Karen quietly shouldered the pain and guilt from Alice’s sacrifice and made it his mission in life to find a way to save Alice, to the exclusion of all else.

Karen’s character and motivation have all the hallmarks that one would expect the main character of a video game, its avatar, to have:

- Like Kasane and Yuito, he has the ability to deploy a wide range of psychic powers, albeit on his own rather than through SAS connections.[18]

- Karen is the only entity besides the avatars that the story represents as able to reliably deploy a Brain Field on his own, a sign of his mental fortitude and combat abilities.[19]

- Karen has the motivation of an avatar: the guiding desire to rectify something he recognizes as unjust and broken within the universe (Alice’s transformation), and this motivation stems from a character that has been robbed of all agency, thereby avoiding the paradoxes of Yuito (fitting the model of Ocarina of Time, Final Fantasy IX, and NieR, as we discussed earlier).

In spite of his aptness to serve as an avatar that would be able to fulfill his goal of saving Alice, Karen finds himself entirely outside the radiating glow of the player’s agency. Beyond suffering the loss of a loved one at the hands of a capricious and indifferent world, Karen encounters perhaps even more painful indifference from the player: his personal tragedy simply doesn’t factor into the world of Kasane, the conduit for the player’s attention in Scarlet Nexus’ world. Given that the power and value of all entities within that world are governed by the extent to which the player attends to them and integrates them into the plot, Karen seems to be at a tragic loss as to how he can avail himself of the power he seems to deserve as a means of bringing Alice back.

But remember that Karen’s drive is unparalleled and indefatigable. When someone like Karen is faced with a world in which the avatar’s story is not about his goal, he takes measures to make it about his goal.

Karen Travers’ Unique Antagonism

In this day and age of literary video games that recognize the need for complex characters, it’s oftentimes less appropriate to speak of “heroes” and “villains” than it is to speak of “protagonists” and “antagonists”: heroes and villains connote a sense of being in the moral right or moral wrong, whereas protagonists and antagonists are defined in terms of their relationships with a plot’s progression, with the protagonist favoring the movement toward the plot’s goal (literally “in favor of the struggle”) and the antagonist working against fulfillment of that goal (“against the struggle”).[20] Even within this paradigm, though, Karen is an unusual character: rather than acting to foil the protagonist’s goal, he acts to try to divert the story’s entire plot to instead realize a different goal.

The core conflict of Scarlet Nexus’ plot, convolutions caused by the Red Strings aside, is the conflict between Suoh and Seiran as Seiran secedes from New Himuka. The two have different philosophies with regard to psionics, Others, and government: Suoh tries to augment psychic powers through human experimentation, develops and implements technology to turn humans into Others, and controls its population through total surveillance (facilitated by Psynet and Arahabaki) and the reprogramming of dissenters’ personalities (“personality rehabilitation”); Seiran pays lip service to the freedom of its citizens, develops technology for the warehousing, rehabilitation, and control of humans who have become Others, and engages in political subterfuge rather than totalitarian control (e.g., the Seiran faction that tries to compel Kasane & co. to assassinate Yuito off the books). As Karen describes it, the fundamental difference between the two cities is their approach to the Extinction Belt: Suoh wishes to eradicate it and its Other Particles whereas Seiran want to do the best it can while maintaining the Extinction Belt in order to avoid the danger of a war against the society on the moon.

Alone, this conflict is a comprehensible one and an interesting story that follows the basic tensions set up from the history of humanity and the Other Particles—and indeed, this is the singular trajectory of the plot after all timeline entanglements are undone and Scarlet Nexus comes to an end. In a desperate bid to save Alice, however, Karen hijacks this conflict for his own ends: he steals the fundamental power of avatars, the Red Strings, in an attempt to massage the storyline into something that can prevent Alice from becoming an Other.

What’s compelling and not immediately obvious about the Suoh/Seiran conflict is that it equally well describes a conflict between two societies and two distinct strategies for saving Alice. By using the Red Strings, Karen is able to insert himself into both sides of the conflict and put both of these strategies into action:

- On one side, Karen travels back in time and kills Yakumo Sumeragi to take his place and create the “source code” of Suoh’s preventative research. Kaito tells Yuito that the will of Yakumo Sumeragi was to “destroy the Extinction Belt and attack the Moon” (shown above); ultimately, we learn that Karen used the Red Strings—presumably many times—to travel back to the time of Yakumo Sumeragi, kill him, and take his place, impersonating him beneath a mask. This might seem like a non sequitur, but the agenda of New Himuka explains why he would approach his mission in this way: the timely annihilation of the Extinction Belt would prevent Alice from becoming an Other (no Extinction Belt with which to accidentally interact); barring that, research advances to understand the powers of psionics and the mechanisms through which humans metamorphose into Others has the potential to lead to preventative treatment helping people like Alice to avoid the fate of metamorphosis, in much the same spirit that Year-2070 Yuito confesses to Kasane that he “continued the research on powers” in an attempt to find an alternative way to close the Kunad Gate.

- On the other side, the Karen paradoxically left in the present leads the Seiran rebellion, takes command of its OSF, and works on measures to ameliorate and cure humans who have become Others. Seiran’s efforts at the Supernatural Life Research Facility, where Alice is kept and cared for after becoming an Other, are all geared toward a better understanding and treatment of humans who have metamorphosed. Brains are processed into food to maintain their sentience; even research into “Other Weapons” could be interpreted as an unhappy consequence of research aimed at better understanding Other psychology. The Karen who heads up Seiran’s forces and enlists the help of Kasane and her platoon is clearly focused on maintaining Other Alice’s quality of life, better understanding her condition, and, in the event of ultimate failure (i.e. Alice’s death), stealing the Red Strings from Kasane and Yuito to start the cycle of killing Yakumo all over again.

Karen is trying to steal the power of an avatar to traverse time, reset its own history upon failure, and try again as many times as it needs to in order to get the plot’s desired outcomes—and, in doing so, he creates a new purpose for the Suoh/Seiran conflict that allows him to simultaneously try to prevent Alice from ever becoming an Other and undo her metamorphosis in the event that his preventative efforts fail. Yet we know from the relative stability of the world’s timeline after Karen erases himself from history that these efforts didn’t actually do much to change the plot or alter history in the way an avatar can. This is where can begin to understand the true pathos of Karen: because he is not the avatar, the most he can do is change the meaning of the game’s plot, not changing the events of the plot itself.

Unable to take the real power of the Red Strings, the player’s attention, with him through time, he is relegated to the role of the game’s main antagonist merely because he wants to make the plot’s focus something other than what it is.

The Crucifixion of Karen Travers

As with many JRPGs, the cipher to understanding Scarlet Nexus’ plot and tragic antagonist lies in its final boss fight and resolution. While the final confrontation between Kasane, Yuito, and Karen at the heart of Sumeragi Tomb is a typically epic final showdown, it’s also a meticulous meditation on Karen’s pain and futility.

Memories of Karen and Fubuki manifesting within Karen’s defensive brain field in the approach to Yakumo Sumeragi’s cold storage unit.

The approach to the final confrontation consists in a massive brain field that Karen (qua Yakumo Sumeragi) has been maintaining as a defensive mechanism protecting his cryogenically preserved body for centuries. This is where Kasane, Yuito, and the player finally learn the truth about what happened to Alice, the source of Karen’s agony. Remember that one of our insights from the comedy of BABE’s appeal to Kasane and Yuito was that the merely descriptive content of NPCs’ lives can’t draw the player’s attention and investment in the same way that the experiential content of avatars’ lives can; it’s salient in this regard that Karen subconsciously leads the avatars and players to experience his history rather than merely describing it to them, even leading them into combat with a memorable Other that he and Alice fought together back during their brief, joint time in the OSF (Dominus Circus). The game’s final “dungeon” is not only a dungeon in the video-game-structural sense of the term, but also a dungeon by virtue of the degree to which these experiences have imprisoned Karen, robbing him of the freedom to desire or do anything else.

The player experiences this pain through the avatar’s navigation of the area and discovery of Karen’s memories, yet she is powerless to focus on Karen as someone to empower: within the plot, his memories are coded as an obstacle that must be overcome in order to reach the story’s conclusion.

The player, Kasane, Yuito, & co. encounter the two faces of Karen we outlined above (Karen as Yakumo Sumeragi and Karen as the rebel leader, shown left & right above) in the depths of Sumeragi Tomb, beyond the reaches of the brain field. Karen the Rebel is as confused as anyone as to why he was rejected when he attempted to travel back in time, only to find that space already “occupied” by Karen as Yakumo, whom he reabsorbs, acquiring all of his knowledge and history. It’s at this point that Karen is in a logical position to steal the Red Strings power from Kasane and Yuito to travel back in time and take Yakumo’s place again, but it’s worth dwelling on what this paradox of the two Karens means in order to see how it prefigures the resolution of Karen’s story.

We only get opaque insights into and speculation on the exact nature of the Kunad Gate and its relationship to the Red Strings, but Wakana, armed with all the knowledge BABE uploaded into her brain, offers one telling illustration of its self-contradiction: she tells Yuito and Kasane that the Kunad Gate is “persisting in a distorted state,” contrary to the typical dimensional holes that Red-Strings users can open and immediately close thereafter; it is distorted because of Yuito’s power resonating with Kasane’s, and “[u]sing a distorted gate for a time jump creates entanglements.” Recalling our analysis of the Red Strings as a representation of the player’s attention, this concept of distortion can be understood as the impossibility of splitting the player’s attention within the game’s plot. It’s impossible for the player to simultaneously attend, and extend her agency in equal measure, to both Kasane and Yuito, which generates the problems of event-relativity I discussed earlier; just so, when Karen attempts to steal the power of the avatar in order to change the trajectory of his world’s history, he is simultaneously trying to personally alter the initial conditions in a causal chain (by guiding the trajectory of New Himuka as Yakumo Sumeragi) and trying to personally participate in the outcome of that causal chain (as the present-day Karen who hopes to live a life with the saved Alice). He is at once trying to take the player’s power in order to alter the plot to which they are attending and also stay within the realm of their attention on that plot so that his desired outcome can become a part of this plot.

Time-travel stories, by their very nature, will always involve some variety of causal paradox: the storyteller’s task is to structure the meaning of that paradox so that it informs a grander, non-paradoxical message or theme within the story as a whole.[21] Karen’s is this kind of story: in a single moment, he is both acknowledging the primacy of Kasane and the player’s attention, while trying to divorce the player’s spatiotemporal agency from that attention for his own ends. At bottom, he is looking for a way to both be the sole savior of Alice and have someone bear witness to his suffering and vindication—and the impossibility of reconciling these two objectives is what tears him apart.

The sequence of three final boss fights against Karen gradually unfurl the determination and pain he harbors, drawing the player further into his pathos before his final resignation from history. The first phase highlights the singular drive that Kasane, Yuito, and the player have seen from Karen the Rebel throughout Scarlet Nexus’ plot, now squarely focused on seizing the power of the Red Strings by force (shown above). The theme of this first third of the fight is insistence on the power of a united team over a singular entity: as Kasane says in both paths through the story after this first Karen is defeated, “No matter how much you use your power alone, all it takes for us is to use the SAS.” This highlights the difference between Karen’s approach to his goal and the teamwork of Kasane, Yuito, the player, & co.: while Karen is able to absorb the powers of many, he acts alone, hampering his capacity to fulfill his goals.

But of course, Karen isn’t really alone: part of the essence of his tragedy is that his efforts to save Alice are so all-consuming and multitudinous that he has split himself, through countless instances of time travel, into countless versions of himself that bind his entire existence to his impossible goal.

The transition between the first and second phases of the battle with Karen is one of those meticulously crafted scenes whose filmic language tells an entire story with very little dialogue. Frustrated by his inability to overcome Kasane and Yuito, Karen looks down to see shadows emanating from his hand, followed quickly by countless shadowy versions of Karen emerging from that same dark substance. Karen recognizes these as “thousands of hopes and dreams” (shown above) before the shadows overtake him, spilling out of his now-bloodshot eyes as he expresses frustration that the player’s cohort and the entire world are “nothing more but stepping stones” to him yet still impede him. Finally, four titanic Others manifest, each holding one of the flowers that have represented the Red Strings throughout the story; Karen, suspended in a clear pose of crucifixion, is spirited away behind the fan of the Other named Sorrow, at which point the battle to dispatch the Others and Karen commences.

Karen suspended in a gesture of crucifixion by Sorrow, moments before Sorrow hides him behind its fan.

Karen connects the shadow versions of himself to “thousands of memories and hopes,” and the four Others that appear, as Arashi notes in the battle, all seem to emanate from Karen, provocatively named after the emotions that jointly constitute Karen’s pain: one is named Sorrow, one is named Rancor, and two are named Rage. Given what we know about Others’ origins in the metamorphosis of living beings, I think the best available explanation of what’s going on here is that the countless versions of Karen that have traveled through time in previous, failed attempts to save Alice are manifesting in his moment of desperation channeled through the strength of his emotions in concert with the total attention of the player, the force behind the Red Strings and its spatiotemporal distortions. This explains the origin of the four Others not merely as ominous metaphors for Karen’s feelings but actually as alternative versions of Karen from previous timelines who lost themselves in their emotions and metamorphosed into Others through one catalyst or another, transfixed by the Red Strings’ potential as symbolized in the Others’ intense gaze directed as their flowers.

The four Others, from top to bottom and left to right: Rancor, Rage, Rage, and Sorrow.

The setup for this battle is an elegant and moving representation of Karen’s psychology. Through countless failed attempts to save Alice, Karen’s character has faded into faceless shadows of a person, defined by cardinal emotions of sorrow, rancor, and rage; it is Karen’s sorrow for the loss of Alice that tethers him to this prison, perpetually sacrificing him for Alice’s sake and trying to absolve the sins of his continued failure, while his rage pushes the cycle onward ad infinitum, numerically more influential in his mind than the instigating sorrow or the rancor cultivated through this cycle. More ironic and tragic still, despite Karen’s obsession with the Red Strings, the four Others illustrate that he is entirely at the mercy of this power: Kasane, Yuito, and the player are able to undermine Karen’s emotional cycle, knock him off his metaphysical cross, and beat him into submission precisely because the Others’ masks can be manipulated and turned into supermassive projectiles with gravikinesis, the metered-down version of the Red Strings.

While the stature of these Others might initially seem intimidating, the overall tenor of the fight instead calls to mind Fubuki’s mournful expression to Karen after all the fighting is over: “I never knew how much pain you bottled up inside.” This is not the typical case of a JRPG final boss evolving before the avatar’s eyes: this is a case in which the avatars and player are led through combat to understand the overwhelming emotions that have trapped the antagonist in a well-intentioned but self-destructive existential paradox—the only kind of emotional content, sadly, that can make Karen pertinent to the plot.

Once Karen is physically and mentally shattered, his resilient psychology of self-torment broken as the four Others fall, he returns to his state of being alone—but not in the same way as he was alone in the first stage of the battle. Now, the darkness representing his countless other attempts becomes amorphous and swallows everything, crowding out the party’s psychic bonds of SAS and pulling the avatar into a worldview as empty as Karen presumably views life without Alice. One-on-one, the vacant desperation of Karen easily bests the abilities of the avatar: we see this in the fact that Yuito or Kasane alone literally cannot damage Karen. Yet Karen has again overlooked the power of the player and the attention that she and the avatar have paid to the various party members over the course of Scarlet Nexus’ plot: this attention-driven power of the Red Strings, which Karen cannot hope to understand, supercedes the dark noise of Karen’s other timelines and allows the avatar to access their bonds with their friends irrespective of SAS being down, reuniting the party to overwhelm Karen a final time.

In the end, Karen is forced to recognize what was already implicit in the image of his body crucified by Sorrow: limp, hands bound, unable to act, Karen is causally impotent without the attention of the player, no matter how many times he tries to rewrite the story and steal the powers of an avatar.

Once Fubuki and the memory of Alice enjoin Karen to give up the ghost—again lowering his hand in a gesture of surrendered agency (shown above)—Karen recognizes the futility of his paradoxical crusade to both save Alice and experience a life with her. Karen’s recognition of “the end,” in his words, “leaves [him] with only one choice”: unable to seize the attention of the player away from Kasane despite the experiential recounting of his past and the battle with his inner pain, his only option is to erase himself from the causal chain of the story altogether: if he cannot make his story the focus of the player’s journey, then it is at least within the logical limits of his powers as a time-traveling NPC to remove himself as an aspect of the plot.[22] Since the monstrous accident that metamorphosed Alice was her selfless act of sacrifice to spare Karen the same fate, this allows Alice to finally be saved and remain human into the story’s present day, as we see in the story’s conclusion after Karen’s final jump through time to relocate himself to the past without taking Yakumo Sumeragi’s place, ending his entangled cycle of suffering.

The ultimate pathos of Karen Travers is that he exists in a world that has a mechanism that ought to be able to give him what he wants, and the content of his character and pain ought to be sufficient reason to give him access to that mechanism—yet he remains beyond the player’s focus of attention, divorced from the interests of Kasane. In a position where his attempts to change the game’s plot are nothing more than entanglements that must be resolved for the sake of the plot, he can only resolve the paradox of his pain by choosing one or the other: remain in the player’s focus by staying in the plot and accepting Alice’s metamorphosis, or leave the player’s focus entirely to change the substance of that plot in such a way that preserves Alice. For a rancorous Karen who metaphorically erased himself for Alice many timelines ago, this is no choice at all.

The end result of Karen’s self-erasure: rewriting the record of the game’s plot, represented in the credits, such that he no longer factors into any of its constitutive events.

Lack of Agency as Antagonism

Karen’s self-erasure from a world in which value is governed by the player’s attention might seem like an unusual kind of pathos to cultivate in a character, and that’s part of what makes the clockwork of Scarlet Nexus remarkable. However, Karen’s character is also a trenchant exploration of what I see as a rare but especially compelling theme that has been on the minds of a few video-game storytellers here and there for quite some time: antagonists whose primary fault is merely being denied the player’s agency.

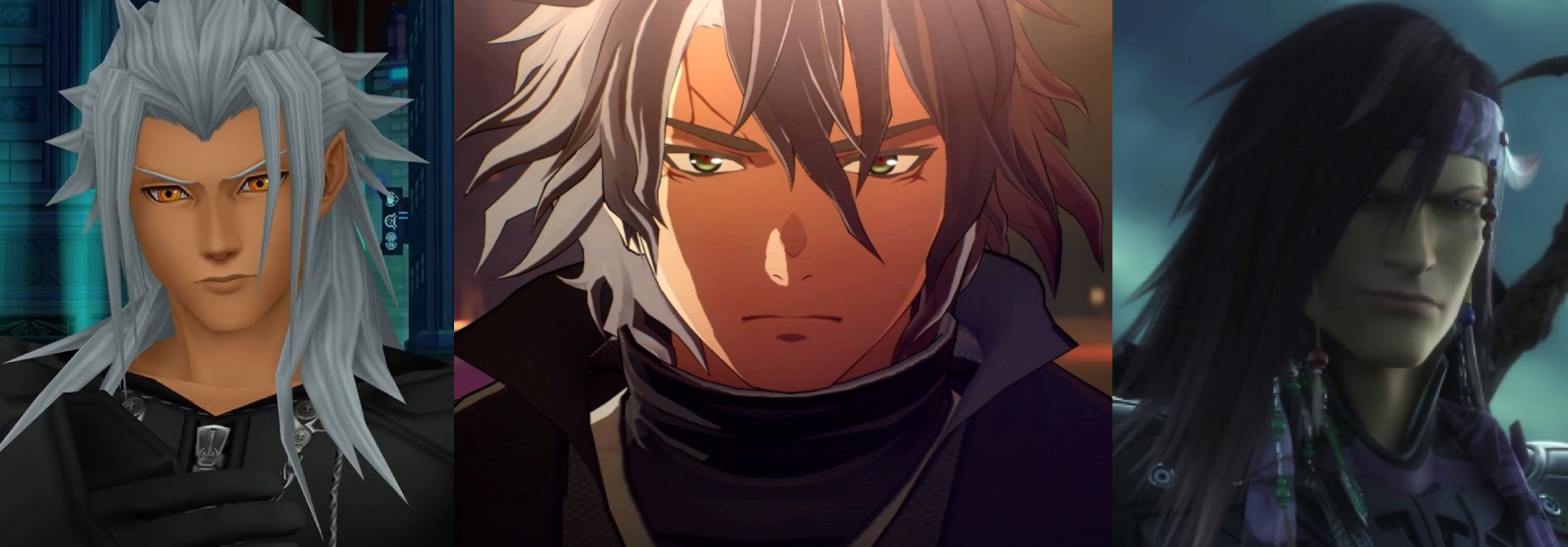

Left to right: Xemnas, Karen Travers, and Caius Ballad, video-game antagonists denied agency.

In his character study of Xemnas in Kingdom Hearts II, Dan Hughes argues that the game’s antagonist suffers from recognizing that he is a character rather than a fully actualized person, that the game’s avatars have the opportunity to be fully actualized because of their relationship with the player, and that he will never be able to access that same opportunity. In my critique of Final Fantsy XIII-2, I argued that the “villain,” Caius Ballad, is left helplessly trying to stop the player and avatar, Serah, as they use their spatiotemporal agency to edit the game’s timeline in countless ways to make it consonant with the events of Final Fantasy XIII, torturing Caius’ ward and undoing his world in the process. These antagonists are sympathetic because they recognize that their formal position within the story precludes them from getting what they want—not unlike Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of An Author or other metafictional works in which characters suffer by realizing that they are representations of people rather than people per se.

Karen Travers takes this theme of video-game antagonists lacking agency to its natural, tragic conclusion: where antagonists like Xemnas and Caius recognize their impotence and suffer for it, Karen desperately tries to seize the powers of an avatar for himself, acknowledging his plight as worthy of this agency and stopping at nothing to redirect the plot in his favor. His pathos is all the more arresting, then, once the player grasps the overall architecture of Scarlet Nexus’ clockwork work, sees the pain of Karen’s wound, and yet discovers all of this far too late to make the plot about Karen in a way that would save both him and Alice.

By erasing himself from his game’s plot, Karen shows the full potential for a video game’s antagonist to influence its story: without the metaphysical power and priority of the player’s attention, the only thing to do is recognize the impact of one’s mere existence on the plot and change the plot by factoring oneself out of the equation. It’s this heartbreaking logic of negating oneself for the sake of another that renders Karen one of the most memorable antagonists in modern storytelling.

- Thanks to Dan Hughes and Stefan Heinrich Simond for review & discussion of an early conception of this analysis on With a Terrible Fate’s weekly podcast. Thanks to Dan Hughes also for review of an earlier written draft of this analysis. ↑

- My very first JRPG was Namco’s Tales of Symphonia, well over 15 years ago; this was the first game that opened a young Aaron’s mind to the possibility that video games could tell stories (not to mention the game that cultivated his lifelong passion for Namco’s Tales series). To say that I’m grateful that With a Terrible Fate’s first publisher-furnished download code came from Bandai Namco would be a gross understatement. ↑

- For further background on method, see my three-stage method for analyzing video-game stories and With a Terrible Fate’s PAX Aus Online 2021 presentation on how to metagame video-game stories. The distinction between literal and symbolic content I’m drawing here also loosely corresponds to the distinction between narrative-event analysis and narrative-grounding analysis I coined in my work on NieR: Automata, but I take that correspondence to be mostly coincidental. ↑

- Remember that, at this point in our current dialectic, my goal is to establish an analogy between (1) the nature of Design Children and the Red Strings, and (2) the general structure of avatars and player agency in the ontology of video-game stories. It’s only in this context that such generalized comments about fast travel, save points, and new game plus mechanics stand: in the context of specific video-game stories, the ontology of these mechanics can be elaborated upon or specified in ways that have radically diverse spatiotemporal and metaphysical implications (cf. the mechanics of time travel in Majora’s Mask vs. the “convoluted” nature of time in the Dark Souls series). ↑

- For more on the role of emotional cadence in the ontology of stories, see J.D. Velleman’s “Narrative Explanation” in The Philosophical Review, 112(1), pp. 1-25. For more on how this kind of emotional cadence factors into the ontology of video-game storytelling, see my “The Role of the Player in Video-Game Fictions,” pp. 13-15. ↑

- Most, but not all: it’s a mistake to claim that the player’s agency in a video game somehow reduces to, is coextensive with, or supervenes on the actions of the avatar. See “The Role of the Player in Video-Game Fictions” for arguments to this effect, as well as a presentation, definition, and defense of the fictional player, my preferred ontology of the player’s role in video-game fictions. ↑

- For convenience and because Yuito is also an avatar I refer to the power of the player, Kasane, and Yuito in the subsequent two sections, rather than the player, Kasane, and Yuito; thereafter, however, we’ll see that, on this interpretation of Scarlet Nexus, even Yuito is ontologically subordinate to Kasane and dependent on the attention of the player and her. ↑

- An exception here is the player who “cheats” the relationship system by initiating Bond Episodes and subsequently skipping all of the cutscenes that constitute the majority of those episodes: in that case, the character in question would gain abilities without really having the player’s attention. But even though this is technically possible and an authorized feature within the game (i.e. a “Skip” button coded into cutscenes, rather than some kind of user-developed exploitation), I think we have reason to treat it as a case of “cheating” in the sense of not fully engaging with the story according to ordinary rules of engagement, in which case it shouldn’t factor into an analysis of the game’s storytelling. I see it as analogous with a reader who merely skim a novel rather than fully reading it, or a viewer who watches a streamed TV series at 1.5x normal speed: the mode of engagement is technically possible, but it’s a material deviation in mode of engagement from the one according to which the story was designed. (Are there “licensed” or “non-cheating” uses of Scarlet Nexus’ “Skip” button, then? I’d suggest that such uses may be limited to players who are on a repeat playthrough of the game and elect to skip a cutscene that they know they’ve already fully witnessed in a previous playthrough.) ↑

- As an aside, notice that the kind of relationship-building system we’ve just analyzed makes much clearer how a relationship-building system such as Code Vein’s makes narrative value out of the impossibility of developing relationships with its supporting cast. Previously, I argued that Code Vein uses its “relationship-building” system between avatar and other party members to distance the player from those party members by showing them to be largely unattached to their own pasts and the avatar to be vampically absorbing their abilities rather than bonding with them. Such an argument might be difficult to buy into without a clearly contrastive case of a relationship-building system that makes narrative meaning out of the cultivation of robust connections between a game’s avatar and party members; Scarlet Nexus is just such a contrastive case. ↑

- It’s worth pointing out that part of the value of playing through both Yuito and Kasane’s stories is that, by viewing Bonding Episodes between party members and the two different avatars, we can create a kind of Venn diagram, the intersection of which can teach us about the party members’ identities independent of either avatar (e.g., the player might say, “If Hanabe shared her aspirations to reform the OSF with both Yuito and Kasane, then that probably reflects something fundamental about her character”). That being said, the very fact that the player’s only means of conducting this kind of analysis comes from comparing and contrasting the interactions that different avatars have with these party members reinforces the fact that the identities of non-avatar party members are subordinate to the experience and attention of the game’s avatars, Kasane and Yuito. ↑

- This clearest description of the computers’ nature, as with most explanations of esoteric elements of the game, comes from Arashi, in the midst of the final confrontation with Karen in Phase 12 of the story. ↑

- As far as I know, the meaning of the name “BABE” remains a mystery at the time of this analysis’ publication, though the consistent stylization makes me think it’s an acronym. Explanations, guesses, or jokes are welcome. ↑

- It’s true that this last example makes it look like Arahabaki is subordinate to Karen despite Karen not being an avatar, but, as I discuss below, Karen’s ability to do this is conditional on his ability to rob the avatars of their unique ability, the Red Strings. ↑

- A small but material distinction: Kasane is an artificial being within Scarlet Nexus’ fiction but a natural instance of an avatar in the fiction’s ontology; Yuito is a natural being within Scarlet Nexus’ fiction but an artificial instance of an avatar in the fiction’s ontology. ↑

- Can any readers tell me that they’ve honestly completed the plot of Skyrim and, if so, what motivated them to do so? I, for one, sunk over one hundred hours into the game without moving beyond the first confrontation with Alduin, then got exhausted and put it down. I used to think that this was a personal failure of mine, but as I’ve discussed it with more people, I’ve found this to be a surprisingly common experience. ↑

- I discuss this particular case study in much more depth in the section of my ontology cited earlier in this paragraph, as well as in an earlier, more formalist analysis of event-relativity (then called “perspectival fixedness”) that you can read here. ↑