Great horror makes the familiar monstrous, and in a video game, nothing is more familiar than the person behind the controller.[1]

Code Vein is an ambitious artwork that I worry many have overlooked because of its apparent mishmash of various genres: it blended the punishing, death-oriented gameplay of Dark Souls with the rich character focus of Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs) and added a vampire motif for good measure. Yet what seems at first glance to be a random mix of concepts empowers Code Vein to present a challenging, horrifying image of what it means for a player to invest herself in games that treat the very characters she’s meant to care about as pawns rather than intrinsically valuable individuals.

I want to convince you that true horror Code Vein is you, the player. More precisely, I want to show you that by setting up a point-by-point analogy between the player and Cruz Silva, the game’s apparent main antagonist, the game frames the player as a kind of metaphysical vampire: a horrifying entity that parasitically engages with the world of a video game, sustaining the world for her own sake rather than the sake of the characters within the world.[2] While this horror may seem bizarre and niche at first glance, I ultimately argue that this increasingly common model for video-game storytelling may hold the key to further innovation in players’ relationships to the worlds and stories of games.

I begin by articulating precisely what features of Code Vein come from Dark Souls, JRPGs, and vampire stories. Then, I show how the game presents Cruz Silva as its main antagonist—and how she ultimately functions as a mirror to reveal the vampiric nature of the player as the true antagonist. After that, I step back to examine how the blend of elements from Dark Souls, JRPGs, and vampire stories unexpectedly managed to trick the player into taking on the role of metaphysical vampire without even realizing it. Finally, I explore how we can view Code Vein as a blueprint for a new way of telling stories about the ethics of players and video-game worlds.

(Be warned: spoilers for Code Vein abound.)

What “Anime Dark Souls” Really Means

The downside of having shorthand for everything we’d ever want to talk about is that the nuance of new stories gets lost in our rush to compare them to those stories with which we’re more familiar. In reality, Code Vein’s unique blend of elements from games like Dark Souls, Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs), and vampire stories is precisely what enables it to slyly turn the player into a monster without their even realizing it—but you wouldn’t intuit this by simply knowing the game as “anime Dark Souls.”

In that spirit, before I can articulate the exact kind of monster that the player of Code Vein is, I want to articulate just what the game borrows from these three genres so we can see the storytelling sleight-of-hand that makes the player monstrous.

From Dark Souls, Code Vein borrows gameplay that emphasizes an avatar dying many times in the course of trying to progress through the world of the game before actually succeeding in making progress. One of the many elements of the Dark Souls series that other games have sought to emulate is that of an unforgiving world whose labyrinthine paths and aggressive creatures lead the avatar to die many times as the player fails, learns, and retries brief stretches of the adventure before finally gaining enough skill to make an iota of progress—at which point the cycle typically begins anew.

This is the mechanical foundation of Dark Souls, upon which the game and the series built robust meditations on futility and the Sisyphean task of making meaning in the face of incorrigible meaninglessness. Code Vein builds a different structure upon that same foundation, with the player flinging the avatar—a Revenant, or a human corpse that has gained the ability to reconstitute itself nearly infinitely after death by bonding with a Biological Organ Regenerative (“BOR”) Parasite that connects to its heart, pumps its own blood through its veins, and takes control of all its vital functions—into death after death, only to see the avatar endlessly respawn at blood springs, Code Vein’s version of Dark Souls’ proverbial bonfires.

From JRPGs, Code Vein borrows storytelling anchored in complex, evolving, explicit relationships between a wide array of characters. While there are exceptions to every rule, chances are good that your favorite JRPG features a team of diverse and unlikely companions where other games might feature a standalone avatar. A game like Xenoblade Chronicles or Final Fantasy VII Remake is identifiable to many as a JRPG, among other reasons, because of the amount of time—and number of cutscenes—committed to developing and explaining the relationships between the four or more characters embarking on the game’s central quest together.

In interactive stories featuring a number of main characters, it makes sense, as a practical matter, to commit this focus to ingratiating the player with those characters such that she would actually want to spend the 60-80 hours typical of a JRPG helping these characters to achieve their goals. Code Vein is straightforwardly a JRPG in this regard: it features a ragtag group of seven core party members, including the player’s avatar, each with their own histories and motivations for embarking on a quest to save their world from impending annihilation—each with many accompanying opportunities for the player to learn about his or her backstory if the player should so desire.

This tableau preceding the party’s battle with Mido encapsulates how Code Vein blends Dark Souls with JRPGs: ahead of a challenging boss fight inviting many deaths, a lengthy cutscene has explicitly articulated Mido’s “evil plan,” and previous cutscenes have explained exactly what motivations the party members in the foreground—in particular, Louis and Yakumo—have for seeing Mido fall.

From vampire stories, Code Vein borrows the legacy of deathless beings who sustain themselves by preying upon power imbalances between themselves and others. Vampire stories, through centuries of storytelling in different contexts and different media, have spun allegories for everything from a fear of infection to a fear of sin. At a structural level, though, stories of bloodsucking vampires represent existential power asymmetries: not a relationship of master with slave, but rather a relationship of a deathless entity—the vampire, who sustains himself by literally absorbing the substance that sustains the life of mortals (blood)—to those more fleeting, death-apt beings who are nothing more than food to the vampire. The former is immortal by virtue of its parasitism on the latter.

Bela Lugosi defining vampirism in Tod Browning’s 1931 Dracula.

Code Vein’s overt focus on blood consumption belies the subtleties of how vampirism permeates its post-apocalyptic world. Revenants consume blood in order to sustain the BOR Parasites that control their bodily systems in exchange for transcendence from death; these blood needs are satisfied by a combination of human sources (willing and unwilling) and blood beads, encapsulated blood generated by blood springs. Yet we later learn that blood springs and their concomitant beads are sourced from the Revenant tasked with housing the heart of the deathless “Ur-Vampire” intended to govern all Revenants (Karen, bearing the Relic of the Heart)—and this sets the stage for the metaphysical vampirism that invites the player into the role of monster.

For our purposes, then, to say that Code Vein is “anime Dark Souls with vampires” is to say that Code Vein tells a story focused on a diversity of characters with robust backstories progressing slowly and meeting countless deaths in a world characterized by parasitic power relationships sustaining those who have transcended the finality of death. With this analysis in hand, we’ll be better poised to understand how this exact, unusual mix of elements from different genres of storytelling turns Code Vein’s player into the most horrifying vampire of them all.

The Red-Herring Antagonist: Cruz as a Villain and Cruz as a Mirror

In Cruz Silva, the player of Code Vein is presented with a character that looks like the game’s ultimate antagonist but is actually a kind of mirror: by setting up an uncanny analogy between the character of Cruz and the role of the player, the game lulls the player into a false sense of complacency before opening her eyes to her own monstrous nature.

To show you how the character of Cruz leads the way to analyzing the player as a metaphysical vampire, I’m going to tell you a story giving a broad overview of Cruz’s role in the story of Code Vein; then, I’m going to tell you a very similar story about the player of Code Vein by changing only a few words in the story about Cruz. By comparing three “Story Events” pertaining to Cruz and the player, the act of playing Code Vein—and, indeed, playing many video games—will become more insidious than it may initially appear.

Cruz as Villain: The Frenzied, Deathless God

Cruz Silva, Queen of Revenants, in a frenzied state, preparing to attack with her Thorns of Judgment.

Before understanding Cruz’s role as the Queen of Revenants, we need to understand what necessitated Revenants and a Queen in the first place.[3] Prior to the events of Code Vein, the world was ravaged by a cataclysmic event called “The Great Collapse,” which introduced eldritch, violent beasts called “Horrors” into the world. This was the context within which BOR Parasites were conceived as a way of creating Revenants:

Queen Story Event #1: BOR Parasites allow hosts to transcend death at the cost of humanity, becoming flawed supersoldiers to fling against Horrors.

However, BOR Parasites introduce an unexpected problem for Revenants: bloodthirst, a craving for the consumption of blood, which, if not satisfied, will cause the Revenant to frenzy, becoming overstimulated by the BOR Parasite and ultimately, if the bloodthirst is not quelled, causing the Revenant to lose its mind and become little more than a hollow, violent shell (called “Lost”). In an attempt to free the Revenants from this crippling flaw:

Queen Story Event #2: A single, deathless entity is introduced to govern those supersoldiers and quell their bloodthirst.

The creation of this entity was the goal of Project Q.U.E.E.N., which conducted experiments and blood infusions on Cruz Silva, a test subject with remarkably strong will, turning her into a transcendent, unique kind of Revenant capable of manipulating blood and exercising an almost divine kind of agency that puts her in the desired position to govern and manage the thirst of Revenants.

This plan goes awry when Cruz herself frenzies, turning from a beneficent bastion of hope into a cataclysm rivaling The Great Collapse. The remaining Revenants take up “Operation Queenslayer” in an attempt to kill Cruz—yet, although the player’s avatar is able to defeat Cruz during this operation, the profound immortality with which she had been endowed by Project Q.U.E.E.N. prevented her from being killed with finality.

In the absence of the possibility of permanently annihilating Cruz:

Queen Story Event #3: The only way to quell that entity’s own madness is to distribute her being across strong-willed entities from that world.

The best that the surviving Revenants can manage is separating the body of Cruz into discrete “Relics” and binding those Relics to individuals who have sufficient willpower to resist their influence (called “Successors”), effectively becoming living prisons preventing Cruz from reconstituting herself and wreaking havoc upon the world’s population once again.

Cruz as Mirror: The Frenzied, Deathless Player

The horror I found in Code Vein wasn’t its desolate world, nor its ruthless monsters, nor even the Horrors of The Great Collapse: my horror came from the gradual realization that Cruz, for all her metaphysical and vampiric quirks, was holding a mirror up to exactly what I was doing as the player of Code Vein. The story of Cruz’s horrific and tragic transformation was quietly mirroring the player’s transformation into a metaphysical vampire.

To reach this realization, we have to tell the story of what it is for a player to tell the story of a video game.

Think first in very general terms about what a video-game story is. It’s a work of fiction representing the goings-on of characters: complex semantic objects that (typically) aim at representing humans or something human-adjacent. However, the structure of many video-game stories—including Code Vein—give these characters unusual, distinctly non-human qualities: (1) the characters are not able to act and make decisions on their own and (2) if the characters are killed by the many enemies that populate their world, they are able to “respawn,” avoiding the finality of death in one way or another.[4]

In other words:

Player Story Event #1: The structure of video games allows characters to transcend death at the cost of humanity, becoming flawed semantic objects to fling against antagonists.

In order for this unusual sort of semantic object to successfully approximate a human, an actual human needs to intervene: someone of flesh and blood has to pick up a video-game controller and allow her own decision-making abilities to guide the character’s actions in a way that seems believably human. This player exists outside the character’s world, deathless and otherwise beyond the reach of all the hazards that threaten the character itself—and yet, the player is able to “reach into” that world through the controller and make the character whole through the act of playing the game:

Player Story Event #2: A single, deathless entity is introduced to govern those characters and impute them with humanity.

But it’s not enough to simply hand the player a controller and expect that she will commit to caring about these characters enough to treat them as humans: if the player does not genuinely care about the characters in the game she is playing, she runs the risk of viewing and using them merely as tools. The other side of video-game stories, after all, is that they are part of games: if the player is not given reason to be invested in the constituents of the story, she may revert to seeing the video game merely as a game, its characters mere chess pieces to be dispassionately used in order to achieve what is not the end of the story but rather a mere win-condition of the game.

So:

Player Story Event #3: The only way to stoke that entity’s own humanity is to ingratiate her with the most compelling characters from that world.

This perspective on player engagement provides an alternative explanation of JRPGs’ heavy focus on exposing character relationships and motivations, which I mentioned as a key element that Code Vein integrates into its own storytelling: if a player is going to commit tens or hundreds of hours to accomplishing the mission of a party of characters, the story ought to be structured in such a way as to make her not merely interested in one character but rather invested in the stories and motivations of all the party’s members.

To borrow from Kingdom Hearts for the sake of analogy, this story of player engagement claims that players need to be invested in characters in order to treat them as the people playing chess rather than as the chess pieces.

In the character of Cruz Silva, then, we have the haunting image of what can happen if a capricious, immortal entity with agency over an entire world—an entity structurally analogous to the player—loses any reason to treat the beings of that world as human.

Of course, the player of Code Vein might still be breathing easy at this point, telling herself that she always cares about the characters of the games she plays and that she is therefore never at risk of “frenzying” as Cruz did. Unfortunately, there’s a further problem for the unsuspecting player: Code Vein’s narrative structure goes out of its way to prevent the player from becoming invested in its characters, turning her from a beneficent, god-like entity into a metaphysical vampire.

Code Vein and Metaphysical Vampirism: Sustaining a World to Feed Off of It

Code Vein distances the player from investment in its characters through (1) punishing gameplay that encourages the player to focus more on mechanical execution than engagement with its story and (2) making it difficult and underwhelming to access the backstories that would ordinarily lead the player to be further invested in its core cast of characters. The consequence, I argue, is metaphysical vampirism: the positioning of the player in the role of maintaining the game’s world merely for the sake of playing the game, rather than for the content of its story.

The Challenge of Focus

In defining Code Vein’s relationship to Dark Souls and the genre of video-game storytelling that has arisen around it, I referred to “gameplay that emphasizes an avatar dying many times in the course of trying to progress through the world of the game before actually succeeding in making progress.“ The upshot of this from the player’s perspective is that, all else being equal, she has to allocate more focus to the operational task of progressing through the game (defeating enemies, navigating convoluted and dangerous areas, etc.) versus other potential objects of focus—for instance, investment in characters and their evolving relationships.

The threat of death around every corner changes how a player engages with a game’s world and story.

This is fairly typical of any video game that’s coded, for better or worse, as a “Dark-Souls-inspired” game. What’s atypical in the case of Code Vein is the manner in which this focus on technical execution of game mechanic integrates with the ontology of its main characters—that is, the Revenants—in order to yield a disturbingly cohesive narrative experience of total estrangement of player from characters.

While Revenants persist beyond death by virtue of their BOR Parasites, death does not leave them unscathed: over the course of many deaths, Revenants lose their own memories, manifested physically in the form of “Vestiges” (shown above) that may be discovered and probed by the player and her avatar throughout the course of the story. In an unexpected way—particularly for a game borrowing character-driven storytelling from the genre of JRPGs—this puts the characters of Code Vein on a par with the player, for both the player and the characters tend to lose their broader recall of the story and stakes of the world in proportion to the number of times they must experience failure before making any progress.

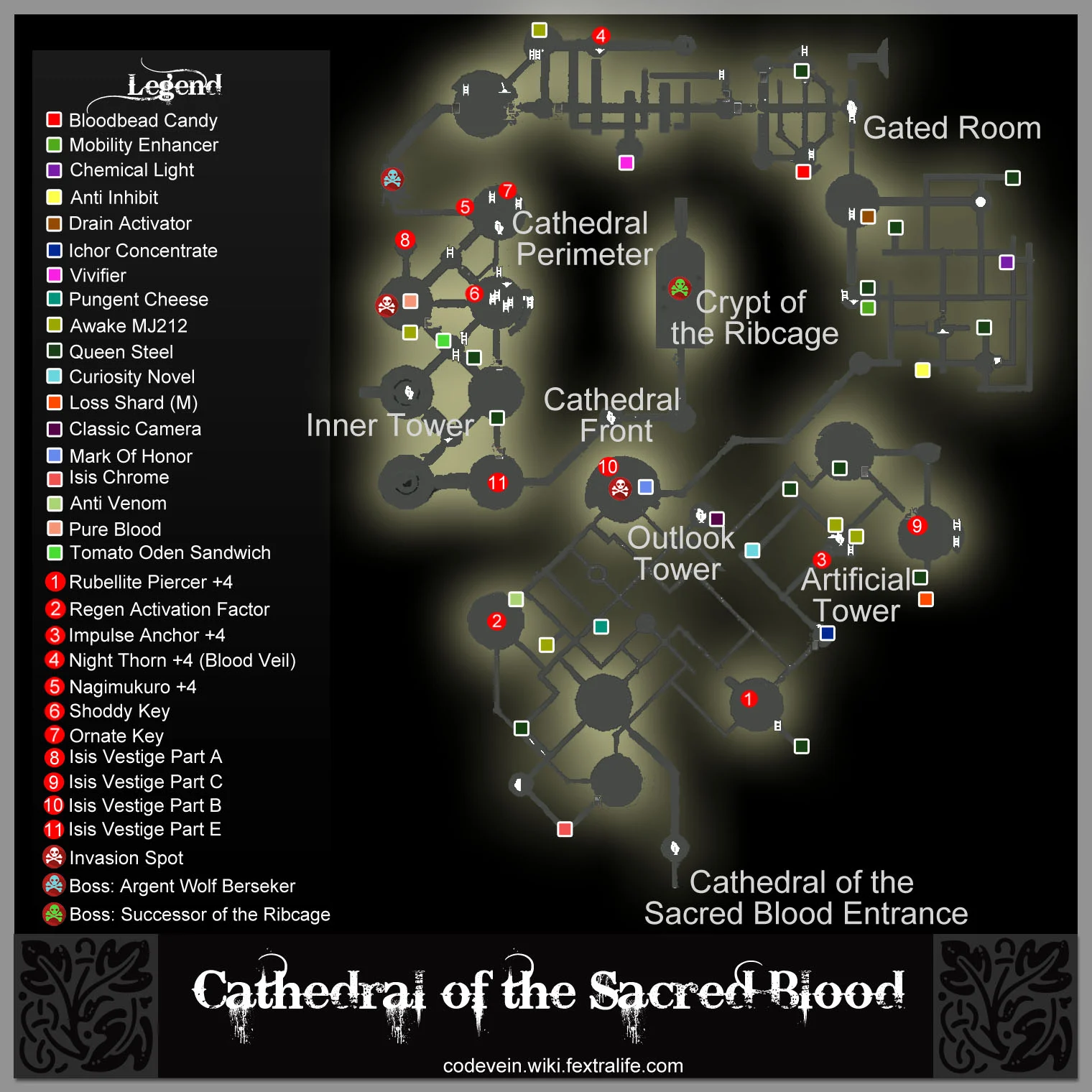

This aspect of Revenants’ persistent yet fleeting existence already distances the player and characters from the backstories that would ordinarily bond the player to her playable subordinates, but the narrative dynamics of the Vestiges push this estrangement even further by (1) making it hard for the player to find the Vestiges in the first place and (2) tempering the reward for finding those Vestiges by rendering the Revenants to whom those Vestiges belong much more indifferent to the reclamation of their past memories than the player might reasonably expect.

A representative map of an area in Code Vein. Notice how challenging it would be in such an area to make a point of locating all the Vestiges—marked Numbers 8-11—in a video-game-storytelling mode that requires significant focus on mere survival while navigating to the boss.

In regions with convoluted paths and enemies keeping nearly constant pressure on the avatar, it can be challenging enough to reach the boss and progress further in the story without worrying about hunting down the Vestiges that are often well off the beaten path. Adding insult to injury, though, those players who do put in the effort to find and restore the memories contained within the Vestiges are met with a more tepid response than they might expect from the Revenants to whom those memories belong.

Allowing the avatar’s companion, Io, to restore Vestiges lets the avatar wander through the memories contained within, witnessing them represented as spotlit tableaus in abstract space. It is implied that the character to which those memories belong also gains access to them by virtue of the avatar committing this act, for after the experience of the memories concludes, that character reflects on the content of the memories in a conversation with the avatar. Yet despite the characters thanking the avatar for collecting their memories and often asking the avatar to collect more Vestiges if possible, the restoration of characters’ memories doesn’t seem to make much of a difference to the characters, inviting the question of why the player is going to the trouble of collecting Vestiges at all.

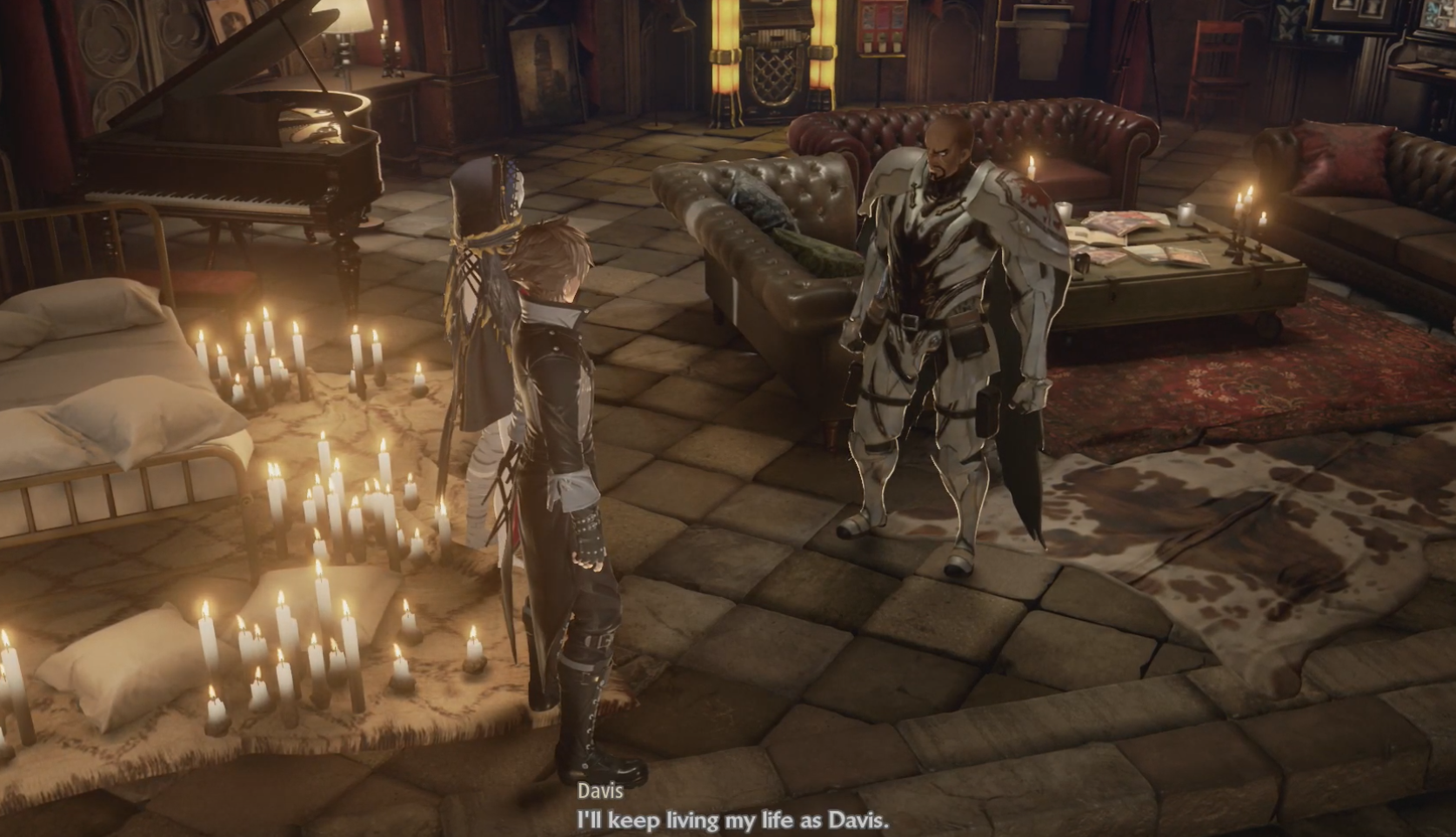

Davis’ memories are a particularly salient example of these Vestige mechanics. By collecting the Vestiges of Davis and Naomi, one of Davis’ old companions, the avatar is able to learn—and cause Davis to learn—that Davis went by “Tyrone” back when he was human and had a fiancée named Jessica, who was rescued from rogue Revenants by Naomi and sent to a government shelter. Davis thanks the avatar for restoring his memories and allowing him to learn about the fates of Jessica and Naomi, but he explicitly refuses to go in search of either of them, despite his once having feelings for both of them and despite both of them putatively still being alive.

This is an unusual and unsettling mode of accessing character backstories and building relationships, something that’s typically the bread and butter of how JRPGs ingratiate their players with their characters. In a game that features a perfectly realistic and playable memory from the avatar’s own past (the memory of Operation Queenslayer), the memories of other characters seem like dim gestures by comparison, and those characters, so long divorced from their memories, seem to view those memories more like stories of people to whom they bear a vague resemblance, rather than aspects of their own identity that would incentivize them to actually behave differently within the story.

And indeed, giving these characters back their memories won’t do anything like give those characters new abilities or motivate them to pursue people from their past—in fact, the most obvious “reward” for restoring Vestiges is not empowering the characters to which the Vestiges belong, but rather giving the avatar new abilities.

Davis’ Blood Code, which gives the avatar new abilities as the player collects Vestiges telling the story of Davis’ past.

The avatar, by virtue of possessing the Relic of Queen’s Blood, has the unique ability to absorb and use the Blood Codes of other Revenants, each of which possesses abilities that reflect the Blood Code’s original owner. Many of those abilities are locked until the Vestiges of the Revenant in question are restored, an apt reflection of the avatar being able to better tap into characters’ powers as the avatar comes to know more about the character.

The result of these Vestige dynamics—difficulty of discovery, underwhelming character response to restoration, and material change only to the avatar—is that the player is naturally encouraged to reconceptualize the game’s primary mechanic for learning more about characters as a mechanic for improving their avatar’s ability to navigate and conquer the ruthless challenges of progressing through the story. Rather than becoming more attached to characters, the player uses those characters—including their very memories—as a means of progressing through the story.

That story through which the player progresses, of course, is one of preserving the world in the face of imminent annihilation—but if the player does not manage to truly invest herself in the characters of the world, then to what end is she really preserving that world? This is pure vampirism in the sense I specified earlier: the deathless entity of the player is sustaining herself by siphoning mere mechanical utility from others.

Metaphysical Vampirism

By establishing a haunting analogy between Cruz and the player and subtly distancing the player from the game’s characters, Code Vein turns its player into a metaphysical vampire: an entity that, rather than feeding on an individual for sustenance, feeds on an entire world in order to maintain her parasitic existence.

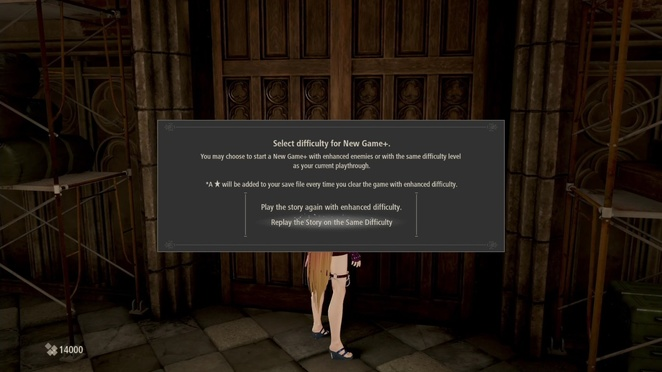

The story of Code Vein presents three possible outcomes, each of which sustains the game’s world at the cost of sacrificing one or several characters, and, following the ending, the player is provided the opportunity to take their avatar and start the whole story over—endlessly perpetuating the world for the sake of the player rather than those characters who actually live within the world.

From left to right: scenes from the “Heirs” ending, the “To Eternity” ending, and the “Dweller in the Dark” ending.

The “Heirs” ending is particularly instructive in this regard: if the player proceeds through the game in as tactical and disengaged a way as possible—represented by not bothering to restore the memories of any of the Successors whose frenzying the avatar must quell, killing them rather than saving them—then the avatar ultimately absorbs all of the Queen’s Relics and becomes a reincarnation of the Queen herself.

The avatar reincarnating the Queen in the “Heirs” ending.

It’s fitting that the ending that most reinforces the callousness of metaphysical vampirism literally identifies the avatar, the conduit of the player’s agency, with the Queen, the other transcendent, vampiric entity that so resembles the player. In fact, given what we know about BOR mechanics using blood to manipulate all functions of their host Revenant, it’s not implausible to suppose that the avatar bearing the Queen’s transcendent blood is precisely what allows the avatar to be controlled and manipulated by the player, a metaphysically vampiric entity that transcends yet interacts with Code Vein’s world in a way functionally similar to the Queen.

Once the rest of the party recognizes the avatar’s identity with the Queen, Louis strikes the avatar down and the party becomes the new group of Successors, sacrificing themselves to act as cages for the Queen’s Relics and thereby ensuring the perpetuation of the world.

Though the other two endings superficially seem like “better” outcomes, they don’t present any opportunity for the player to truly abnegate her metaphysical vampirism. “To Eternity,” the outcome of the game if the player saves only some of the frenzied Successors she faces, sees the avatar (along with Io, in a supporting role) sacrificed to literally take the place of Gregorio Silva and maintain the world’s status quo. “Dweller in the Dark” is the most deceptively parasitic of the endings, for it sees Io absorbing the Queen’s Relics and sacrificing herself to become an endless fount of blood beads to sustain the world; while the avatar and party subsequently set off to adventure into the parts unknown beyond the Gaol of Mists that circumscribed the game’s world, the game immediately invites the player to restart the story with the same avatar, reconceiving Io’s grand sacrifice as yet another way of maintaining the world for the sake of the player playing the game again.[5]

The option to start the story again upon completing any of the three endings.

The longer one stares at it, the more Code Vein becomes a delightfully deceptive puzzle box: it purports to have a more robust and narratively central cast of characters than Dark Souls and its cousins, yet the ways in which it encourages players to use those characters in order to progress makes the player into a vampire far more terrifying than any blood-fueled Revenant: the player looks in the Queen’s eyes and sees a mirror to her own role, playing the game simply to sustain the game’s world so that she may continue to play the game, with no room for direct investments in characters who barely remember their own identities beyond their function as soldiers.

Toward an Ethics of Player-World Relations

Code Vein shines for telling a horror story that makes the player the monster and makes sure she doesn’t realize this until it’s too late. Beyond this being an intrinsically compelling story, though, I’ve found myself returning to Code Vein repeatedly as a jumping-off point from which we can begin to explore more sophisticated meditations on ethics in video-game storytelling.

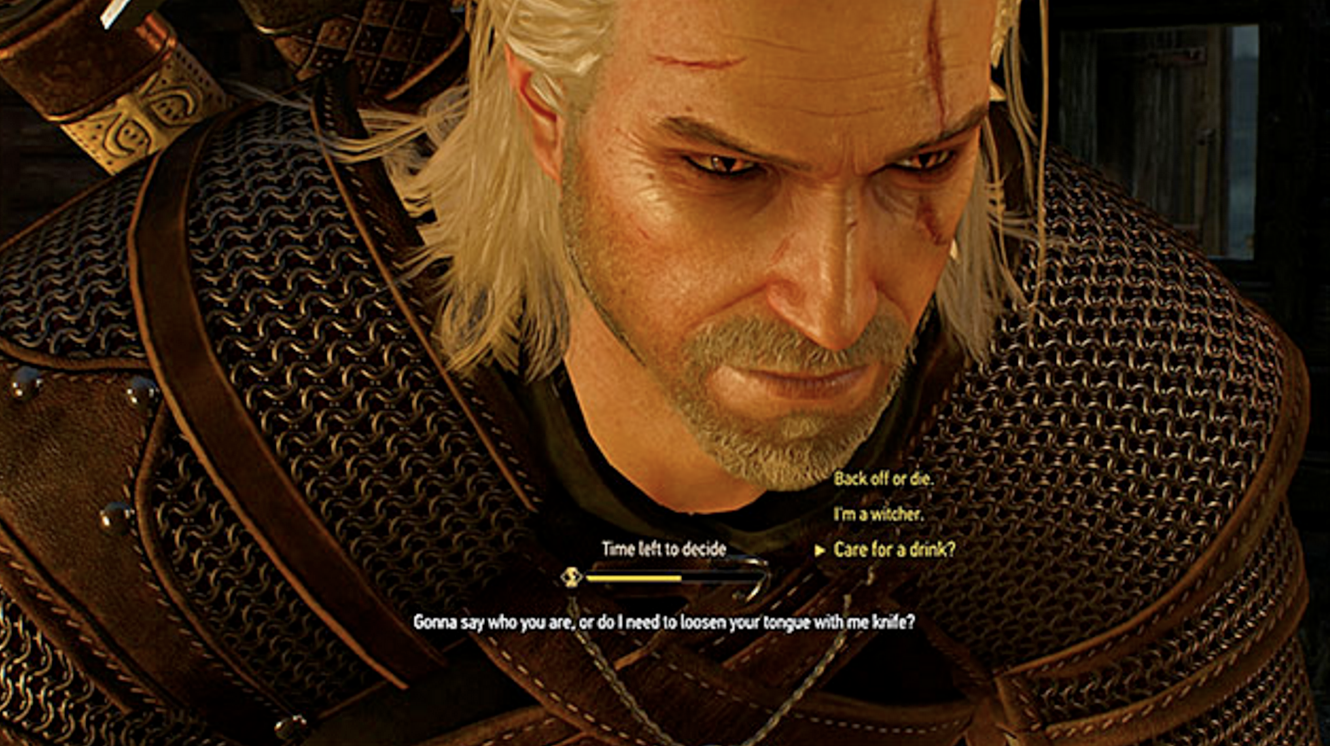

For many years, the storytellers of games have recognized that video games’ interactive nature makes them an apt playground for moral decision-making: at various moments in the story, the player may choose to make it the case that her avatar takes different actions with different moral valances. In many games, such as the Fallout series, those different actions are explicitly coded with different “good” or “bad” karma points; other games, such as The Witcher 3, have been lauded for offering the player decisions that have non-obvious consequences and no clear “morality value” assigned to them, encouraging the player to think more directly about the substance of her choices rather than optimizing for build an ideally “good” or “bad” avatar.[6]

While this variety of decision-making within games can be interesting, it doesn’t go far beyond fairly basic matters of practical ethics. Even the choices offered within The Witcher 3 sit well within the realm of classic-but-tired ethical thought experiments such as trolleys and murderers:

- A runaway trolley is barreling toward two workers on the track. You can pull a lever to divert the trolley to a different track where there is only one worker. Do you pull the lever?

- You’re hosting your friend at your home. A murderer knocks on your door, says he wants to kill your friend, and asks you if your friend is in your house. Do you lie or tell the truth?

What excites me about Code Vein is the fact that it shows the path to contemplating ethical questions that much more thoroughly take advantage of the special nature of video games as a storytelling medium. Forget, for a moment, about the ethics of the avatar’s actions, and think about the ethics of the player as a god-like entity who is able to manipulate the world of a video game from outside of that world—the entity whose engagement is the direct goal of that entire world. What are good and bad ways in which the player can relate to that world? What does the moral universe of a video game look like to the player who steps back from her avatar and thinks about her own relationship and responsibility to the content of the game’s fictional world?

Code Vein has shown us just one of many possible stories that can be told when we take this perspective: the player, separately from her avatar, can be the monster in a horror story, bending the video game’s entire world to her will for the sake of detached and perpetual entertainment. There are many other stories that can make the player distinctly heroic, monstrous, pitiful, and many other attributes in this light; some of these have already been published, and many more are lurking in the imaginations of storytellers and gamers.

It’s my hope that other games will pick up the gauntlet that Code Vein has thrown and allow us to explore the full range of possible roles that we can assume as players. In my experience, it’s the substance and implications of those roles, much more so than any particular action taken by an avatar, that keep the player thinking about a game long after she’s put it down.

- Thanks to Dan Hughes, Matt McGiil, Shannon Diesch, PAX South 2020, and PAX East 2020 for helping to develop the concepts of this article in their previous iterations as convention presentations. Those who would rather watch than read can find a recording of With a Terrible Fate’s panel analyzing games inspired by Hidetaka Miyazaki—including Code Vein, Hollow Knight, and Nioh—here. ↑

- For clarity’s sake, it’s worth pointing out that I am not claiming that the developers of Code Vein, as a matter of empirical fact, designed the game with the intention of making the player a metaphysical vampire in the way I specify in this article; analyses that speculate about the intentions of authors are not what interest me. What I’m interested in is the most cohesive understanding of the overall ecosystem of a game’s story and everything it implies for the player participating in it, regardless of whether or not its creator intended for the ecosystem to be most conducive to that particular understanding. It’s in that spirit that my analysis contends that this novel way of understanding the role of the player in Code Vein is one that is especially illuminating and explanatory in light of the game’s overall storytelling structure, whether or not the developers had it in mind when creating the game. ↑

- Interesting work has been done to connect the world and events of Code Vein to the God Eater corpus, another of Hiroshi Yoshimura’s works. I don’t intend to take a position on that relationship here; rather, I’m analyzing Code Vein as an artwork on its own terms. I believe that the substance of my arguments in this analysis remains the same irrespective of Code Vein’s relationship to God Eater. (More context on the relationship between these two modes of analysis, which I call ‘Narrative-Grounding Analysis’ and ‘Narrative-Event Analysis’, can be found in the “Preliminaries” section of my article analyzing the grounds of humanity in NieR: Automata.) ↑

- This isn’t equally applicable to all video games that feature avatars and party members that die frequently: in many games, the best explanation of what happens when a character respawns is simply that the player has returned to a moment in the game’s history before that death occurred, meaning the character itself isn’t really the kind of thing that can avoid death. However, many modern games—including, crucially, Code Vein—make narrative meaning out of their respawn mechanics by offering an explanation as to how and why these characters really are able to avoid death (in Code Vein, that explanation is the BOR Parasites). ↑

- Some might object that this is a hollow criticism of “Dweller in the Dark” because a video-game story simply has to provide a means for the player to restart upon the story’s conclusion, but that’s not a necessary feature of video-game stories at all: in fact, some of the most innovative video-game stories have endings that can only be achieved by the player choosing to irrevocably erase all of the save data representing her progress through the game, effectively preventing herself from further engaging with the game. Thus, the capacity for the player to seamlessly restart the story with her avatar upon the conclusion of “Dweller in the Dark” is an aspect of the game that warrants narrative analysis like anything else. ↑

- Richard Nguyen has the best analysis I’ve seen of this universe of decision-making within games. ↑

13 Comments

K · November 23, 2020 at 7:49 pm

👏👏wow, amazing work sir.

Aaron Suduiko · November 23, 2020 at 8:06 pm

Thanks so much for taking the time to read, K; I’m delighted that you enjoyed it! Hope you get the chance to check out some of our other work as well. Don’t be a stranger!

J · November 23, 2020 at 10:06 pm

Interesting read. I don’t quite agree with the overall premise, and that’s more of a personal stance, but some of your points are off base or opinionated. As far as the connections between endings and starting new game cycles go, the option to start NG+ in Code Vein is in no way indicated to be canon. It doesn’t even make sense in terms of story continuity. It’s purely a game mechanic to facilitate replayability, so tying it to the value of the endings and character sacrifice isn’t logical. To give an example, one of the few games that actually did tie certain endings to NG+ cycles was Dragon’s Dogma. (SPOILERS) If you lose to the Seneschal at the end or use the Godsbane on yourself instead of them, your pawn gets sent to your body at the start of the story, and you get reborn as the red dragon, literally, not figuratively, starting the cycle from the beginning. (END SPOILERS) This isn’t the case with Code Vein. As for difficulty and the corresponding value of finding vestiges, that’s mostly down to opinion. Challenge is relative, and I personally didn’t find that having to explore for character story tidbits devalued anything. Code Vein isn’t particularly difficult or punishing in comparison to many other Soulslike games, and it did a decent job giving relatively frequent Mistle locations for resting in most areas, which eases exploration. Also, and this is mainly a personal issue, you might want to refer to the player with a neutral term. One of your main focuses was Cruz, and the message gets a little garbled when referring to her in the same points as an assumed female player.

Aaron Suduiko · November 24, 2020 at 12:04 am

Hi, J! Thanks for taking the time to read my work; I’m glad you found it interesting. I’d love to share a little more of my perspective with you to clear up where I’m coming from.

I honestly don’t know what people mean when they talk about events “being canon” because, to my ear, that term can mean a number of very different things, but I take your point that choices at the end of a path through the game may not seem to overtly influence the next playthrough in the way that’s true of Dragon’s Dogma or the like. What I’d point out, though, is that data like avatar experience and items (among other things) do carry over to subsequent playthroughs of the game, and I find myself unable to see how there’s a different in kind between Vein and Dogma in this regard rather than a difference in degree.

Footnotes 2 and 4 also come into play here: whether the replay mechanics were intended to “facilitate replayability” or intended to do something else, they still constitute part of the overall video-game fiction and, with respect to the analytical approach I lay out in Footnote 2, are therefore susceptible to interpretation as part of the overall video game story, beyond any singular strip of plot that constitutes one playthrough of the game. That’s especially justified, I think, when, as I discussed in Footnote 4, we have not only theoretical examples but also real-life examples of games that have stark alternatives to these sorts of replay cycles in their own storytelling structures. If you’re interested in a deep-dive into one such example that ends up serving as a very compelling counterpoint to the kind of metaphysical vampirism present in Code Vein, I’d encourage you to check out my analysis of the missing soulmate in Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch.

It’s great that you didn’t have trouble exploring and progressing through Code Vein, but I think it’s a fairly noncontroversial statement that the average player would experience difficulty by virtue of the elements I mention that is has in common with Dark Souls. (Dark Souls itself is a good example of this point: these days, lots of people (not me!) are able to complete that game without being hit a single time, but that fact doesn’t preclude it from being understood to be a difficult game.) Every player is different, so no analysis that analyzes the role of the player in a video-game fiction will be one-size-fits all, but I don’t see how that precludes us from considering what player experiences a given game is naturally conducive to and how that impacts its overall storytelling.

And, for what it’s worth, my habit of referring to the player with “she/her/hers” is a personal one I inherited from a fellow philosopher who had the same habit: he once explained to me that he does this because it costs nothing and implicitly makes fields like philosophy or gaming, which are far too saturated with male bias, more welcoming, even if only a little, to women. I do take the point that it was a little confusing with the Queen/player comparison and I did try to add clarification with that in mind—let me know if there were any particular places where that fell flat, and I’m happy to clarify further.

Hope that helps to clarify my overall project here to you! If you’re interested in digging further into different standards of evidence and approaches to analyzing the storytelling of games, you might also be interested in this separate piece I wrote detailing on a more granular level how we approach those topics at With a Terrible Fate. Cheers!

Tisha · November 23, 2020 at 11:44 pm

Well i guess thats not realy exclusive to code vein though you can say the same about every game basically gamers are just metaphysical vampires i mean take any other game and it still fits dark souls for example the avatar has no choice what its gonna do all it can do is go through lordran dranglaic & lothric slay a bunch of demons gods dragons and just powerful beings and choose to either prolong the age of fire or usher in the age of dark all for the players enjoyment not realy careing for the aftermath of the choices they made but its not just souls like games that this can be said about like i said its true for every game mario kart take control of the racer win the tournament get the prize after its over get prompted to do it again like i get the sentiment of what you were trying to say but to just limit that and say it makes gamers the true villain of code vein is simply something i just cant get behind i mean one part of the article says the game wants you not to care about the characters but the game gives truely heart breaking backstory for the characters like take mary for example her and her brother were (from there point of view) betrayed and abandoned by there care taker so they look after eachother but mary didnt no that her brother was the hole time trying to protect her just as much as she was trying for him he even went and became a successor to save her a might robot hero something jack advised against since it would be hard to maintain he did it anyways all for her he even made a copy of himself to keep her blind to the truth and away from harm like all the characters have powerful stories that make you care for them jack and eva louise and karen even rin and shes only a tiny bit character thats suppose to operate as a shop and thats something not realy any game does non-important npcs dont usually get backstory and good lore code vein went above and beyond to make you care for there characters

Aaron Suduiko · November 24, 2020 at 5:58 pm

Hi, Tisha! Thank you so much for taking the time to read my work and share your own feedback with me. First, I should say, I hope it came through in the piece that I’m a huge fan of Code Vein: I think that its storytelling and cast of characters are wonderful, and I agree with you that the backstories of the characters can be very moving (especially Nicola and Mia’s, as you mention); I only intended this article to show how I believe the game also goes “above and beyond” by putting the character in a unique position of alienation and vampirism relative to those characters and their world.

You are absolutely right that my concept of metaphysical vampirism could be applied to the players of many different games: in fact, whenever a player plays a game and uses its characters as means for merely beating the game rather than intrinsically valuing them, you could rightly apply this concept to her—whether she’s playing Code Vein or Dark Souls or Mario Kart. (I actually discuss this more directly in a presentation I gave on the same topic; I omitted it from the article simply because the article was already rather long and I didn’t want it to become too unfocused.)

I am not trying to say that the concept itself is uniquely applicable to Code Vein; rather, what I’m saying is that Code Vein is unique by virtue of using a blend of JRPG-inspired storytelling and Dark-Souls-inspired mechanics (in the ways I specify in the article) to make its player disposed to taking on the role of a metaphysical vampire only to have her subsequently realize the horror of their vampirism, in a world where she should be caring about the characters that constitute the story. In other words, it is precisely because of the way the game articulates all the characters’ backstories that it is jarring and haunting to the player when she feels herself estranged from those characters; the storytelling simply wouldn’t work if the characters weren’t as thoroughly fleshed out because, in that case, the player would not feel unsettled or horrified by her estrangement from the characters.

One of the consequences of Code Vein’s mode of storytelling that amazes me, Tisha, is exactly how players who are made to recognize themselves as metaphysical vampires are then able to apply that concept to their engagement with other games. In a similar way to what you spelled out in your comment, playing Code Vein actually caused me to reflect back on other games I’d played and wonder how much I’d really cared about the characters in those games. That’s a scary thing to think about, but it’s also a line of thinking that’s encouraged me to get further invested in characters in subsequent games—so I think it’s equal parts a scary and uplifting realization to go through.

In that same spirit, it might be helpful for me to point out that, while you paraphrase me as saying these dynamics make the player the “true villain” of Code Vein, the word I chose—which is related but has a slightly different force to it—was ‘antagonist’. I mean ‘antagonist’ in the sense of ‘a character or entity that obstructs the progress of a story’s protagonists’. I think that’s structurally true of the player whether or not she appreciates the backstories of the characters by virtue of the way in which the game is structured to get her to focus on merely completing it and playing it, making it cyclical and estranging both the player and the characters from characters’ history in a way that obstructs real and final narrative progress.

I think it’s also helpful to consider that a single entity can function as both an antagonist and a protagonist (something I also didn’t mention in the article for the sake of focus). This is another way in which Cruz can be seen as a mirror to the player: she is certainly an antagonist in the sense that the reconstitution of her frenzied state spells doom for the world and is what the party is trying to prevent, but Cruz as a person was also well-intentioned, creating the Attendants and sending the avatar on its quest to try to improve the world and ease suffering. Similarly, the player is an agent who, in my view, advances the game’s plot in a protagonistic way (by making the avatar complete events and progress) yet also is ultimately parasitic on the game’s world, trapping it in endless cycles and distancing the characters from their very compelling backstories for the sake of the game.

I hope that’s helpful, Tisha; as I said, I love the game and am glad to meet someone else who does as well—and, even if you don’t ultimately agree with every point of my analysis, I hope it offers you a new lens through which to contemplate how this game tells such a rich and, I think, masterfully unsettling story. Cheers!

Jt · November 24, 2020 at 12:08 am

I fundamentally disagree with your hypotheses. The worst ending is easily the fastest and most achievable and is obviously punitive about the lack of effort by the player. IE: you don’t give a damn and everyone pays for it. Whereas the best ending, Io (who would have died if everything came to pass otherwise because of the loss of the player) is given a new purpose and thereby saved. Additionally, everyone on the team is restored to their sanity and your mission can continue to save the broader world from the horrors that still exist beyond the protective barrier around the city. It’s not a story about a metaphysical vampire as much as it is a story about someone whose choices and efforts are directly proportional to the success and well being of the player and their comrades.

Aaron Suduiko · November 24, 2020 at 8:59 pm

Hello, Jt! Thanks for taking the time not only to read my analysis but also to offer your own perspective; I hope you found my framework useful despite favoring a different one yourself!

I do appreciate your reading of the endings—in fact, I think it’s especially interesting to consider how our two interpretations might not be mutually exclusive but actually interact with each other to say something else interesting about Code Vein.

I agree that the structure of the story is such that the endings seem like better outcomes based on the amount of effort the player is willing to put in, but I’d reiterate that all of these endings sustain the world only to see the story restarted by a metaphysically vampiric player looking to “play again” (for all the reasons I walked through in the body of the article). Even in the case of “Dweller in the Dark,” Io’s new purpose is the sustaining of the game’s world and does not overcome the capacity or inclination of the player to start the game right over again, despite the party heading off beyond the Gaol of Mists at the end. In my mind, this presents an interesting opportunity to think about the effort/outcome gradient in the endings as yet another level of the player’s metaphysical vampirism: by virtue of the endings being tied to the amount of effort the player is willing to put in and in light of everything else we’ve discussed, the task of “collecting” these endings could become a kind of “metagame” for the objective-driven player to put in the effort to get in all the endings, more focused on something like completionism or merely seeing everything that could happen than on actually achieving the materially best outcome for the sake of the characters. I have a feeling that might resonate with the experience of a lot of players who feel the need not just to experience the “best” ending but rather to experience “every” ending (and I’ll own up to the fact that it certainly describes me: I went back to get the two “worse” endings after getting “Dweller in the Dark” on my first playthrough, an act that now strikes me as especially vampiric!).

In any event, I’m grateful for the opportunity to have teased out this further idea with you; in my experience, you can’t really ever fully appreciate the total scope of an interactive artwork like a video game without putting different interpretations of it into conversation with each other. Thanks again for joining the conversation, and I hope you get the chance to check out our other analyses in the future!

Foisted_Bread · November 24, 2020 at 1:33 am

I love Code Vein, it is a really great game, the only gripe I have and it isn’t much of a spoiler cuz no that hasn’t played wont know what I mean.

There is a part of the game when you become the “mirror” later thru a flashback, some time after that and some story later you become the vessel of blood but you cannot be the vessel of blood because you are not even a part of the project that created vessels.

That is my only gripe about some of the story.

Josh · November 24, 2020 at 3:14 am

Wow, this is a really good article right here. I’ve played through the game a whole bunch of times and I enjoy it a lot, but I’ve never thought about the story this way, this gives me a whole new appreciation for the story. Thanks for the awesome read! 👍

Aaron Suduiko · November 24, 2020 at 4:01 am

Thanks for your kind words, Josh! I’m delighted that you took the time to read it and that it gave you a new appreciation for the story; that’s the goal of literally everything we do here at With a Terrible Fate! I hope you get a chance to take a look at our other work at some point as well. Cheers!

Caymus · November 29, 2020 at 1:12 am

Definitely an interesting perspective, Aaron! I think this interpretation offers a lot to think about, both within and beyond Code Vein. As someone who personally disagrees with the idea of the Death of the Author, though, I find a lot of your analysis difficult to parse. I formulate most of my interpretations as an articulation of what I think the author is trying to do, and in this case, I find it difficult to argue that much of what you discussed was intentional on the part of the developers. But the whole “intentional vs. unintentional” discussion is a monstrous beast, and one I don’t plan on tackling today.

Nonetheless, you proposed a lot of fascinating ideas, and I couldn’t help but consider other games within this framework. Despite never playing it, I immediately went to was Spec Ops: The Line since it accomplishes something similar by essentially projecting the mindset of the protagonist onto the player to show the consequences of that mindset. In the game, the protagonist gradually denies responsibility for what amount to war crimes that he commits throughout the game (Looking at you white phosphorous scene). By the end, he is absolutely deranged and refuses to accept the fact that he has become the real villain of the story, with the stated villain being revealed to have killed himself long before the events of the game.

Spec Ops sees this mindset and draws a parallel to the player. You, the player, committed these war crimes, albeit fictional war crimes, vicariously through the protagonist. If someone were to criticize you for your actions, you would likely say, “It’s not my fault. It’s just a game. I had no control over the outcome.” The catch is: this is exactly how the protagonist sees his own actions. He reasons that it was never actually his fault; it was all the fault of the fictional villain he created in his head. You, the player, abdicate responsibility for your actions in the same way the protagonist does, and the events of the game show the consequences of such a thought process. We all say we don’t have control over the outcome, but we do, somewhat. If we stop playing the game, none of it ever happens. No war crimes, no suffering, no death and destruction. This sort of meta commentary made Spec Ops: The Line the classic it is today, and I see a lot of that commentary in your analysis of Code Vein – although I would argue that the developers of Spec Ops absolutely intended for the game to be that way.

Ultimately, what I am trying to say here is that though I may disagree with some aspects of your analysis, the relationship it describes certainly exists and absolutely should be explored more in the medium. It presents an interesting opportunity to elevate the storytelling of video games even further, and I would hate to see that go to waste. Thanks for the interesting read!

Aaron Suduiko · December 1, 2020 at 11:58 pm

Caymus, always a pleasure to talk games with you, and I appreciate you taking the time to read and contemplate my work here!

You raise a great point about Spec Ops; as I mentioned in my reply to Tisha in this article’s comments section, I absolutely agree that part of the value of Code Vein‘s storytelling is in giving us a framework of metaphysical vampirism that we can apply to our roles in other games. In my view, Spec Ops is actually an even better instance of this than you suggest because there is not exact correspondence between the mindset of Walker, the avatar, and you, the player: the game suggests that Walker is slowly being driven insane by the horrors of war, which is part of what leads him to hallucinate and commit war crimes; the player, on the other hand, is completely sane.

That difference between the player’s sanity and Walker’s insanity is part of what makes Spec Ops‘ condemnation of the player so memorably jarring. It’s not that Walker and the player are companions in guilt who both willingly and rationally bought into the premise of the hellish landscape of Dubai presented in that game: rather, it’s the fact that the player, of sound mind and judgment, willingly chose to keep going through the game and effecting the actions of an insane person who, by virtue of his insanity, cannot be held responsible for his actions in the way that you, the player, can be. (If you’re interested, I cover this further in my “The Role of the Player in Video-Game Fictions.”)

It’s not much of a leap to see that story from a hauntingly vampiric perspective: the player is, one might say, driving her avatar to violent madness merely for the sake of her own entertainment. And, while I won’t dwell on it here (for the sake of brevity and avoiding too many spoilers), I’ll add that the multiple endings of Spec Ops fold very nicely into the commentary about ending-oriented metaphysical vampirism I mention in my reply to Jt in this article’s comments section—all the more so for the fact that, by the end of Spec Ops, poor Walker’s psyche has been totally decimated by the player.

Did the developers intend for the particular kind of epistemic dissonance I outlined above to inform the story of Spec Ops in this way? I don’t know, and that’s my point about method, Caymus: the structural aspects of the story that bring about the above effects exist and yield those effects whether the game’s flesh-and-blood creators intended them or not. I honestly don’t know what an “argument” that the developers intended the game to be that way would even look like, beyond simply asking them what they meant or reading a bunch of interviews and background about them and drawing inferences; such an exercise might be interesting as a matter of biography, but insofar as we’re interested in thinking about the game itself rather than the psychology of the people who created it, I’d challenge you to think about what you’d want to know about the game’s story that could possibly be answered by reasoning about the author’s intention rather than simply reasoning about the content of the work itself.

(By the way, I’m not being flippant in the above statement: I think game developers are amazing and fascinating, and it’s absolutely worth learning about their biographies—that’s one of the reasons why I myself have interviewed some of them in the past! That’s just, in my view, a fundamentally different exercise than understanding how best to interpret an artwork.)

Once an artwork has been created and is out there in the world, an author can certainly tell us how she interprets her own artwork, but it’s not clear to me why an author’s interpretation ought to have any privilege over anyone else’s. While there are many ways into this mindset I’m outlining about literary analysis, I’d invite you to consider two that I find especially fun:

1. Authors who try to privilege their interpretive position relative to their own work after its creation often come off—rightly, in my mind—as comical. J.K. Rowling is a known offender of this, decreeing on Twitter “truths” about her stories that have no basis in the texts themselves. It’s why she’s become a beloved source of parody for publications like ClickHole, poking fun at the fact that it’s silly and baseless when authors try to inject facts into their texts that simply are not there. And, to the extent that the facts the authors are interpreting are in the text, why does it matter that the author, rather than any other reader, is articulating a particular way of seeing them (unless the author is merely offering one of many compelling interpretations and then appending the phrase, “and, by the way, that’s what I intended to do”—at which point we’re back in the realm of studying biography rather than studying the text itself)?

2. There is a conceptual difference between what an author intends to do in her work and what is actually done by her work, even if those two concepts happen to be coextensive in some artworks. My favorite example demonstrating this conceptual difference is owed to Wayne C. Booth in his Rhetoric of Fiction (a text that I can’t recommend enough): in 1702, Daniel Defoe wrote a pamphlet called “The Shortest Way with the Dissenters.” Defoe, a Whig, wrote the pamphlet as an ironic work intended to parody Tory extremists (those in the political party opposite the Whigs). However, Defoe’s irony was so thorough that readers actually thought his pamphlet was a sincere endorsement of Tory views! Defoe, in other words, had created a text that implied an author with different views and intentions than its literal, flesh-and-blood author. As readers, we can always infer a conceptual entity—what Booth calls the “implied author”—that would have created the text in question in order to express certain views, but, as the case with Defoe shows, it’s a matter of contingency rather than necessity that that conceptual author aligns with the literal author of the text. (I discuss this case and some related issues of authorship that might interest you in my analysis of Davey Wreden’s The Beginner’s Guide.)

That’s all to say, Caymus, that I hope you can come to appreciate and engage with this approach to textual analysis because it strikes me as the soundest analytical approach, by a mile, that we have available as analysts. “Death of the Author” is a sad moniker because it makes it sound as though analysts are throwing out anything the author may have intended and willfully creating an interpretation as far-removed from the author as possible. That’s not the case: the approach is merely one of looking at the thing the author created and trying to uncover the semiotics inherent to the various parts that make up the whole of that text. If the author was mindful in crafting her creation, then there may well happen to be a significant overlap between her intentions and the uncovered semiotics—but I fail to see a reason to privilege that overlap, let alone to begin from the point of speculating about an author’s psychology rather than simply reading the text.

Cheers! Appreciate your engagement—and looking forward to your own future articles.