The following is an entry in Tales of Praxis, a weekly series studying the storytelling and philosophy of Bandai Namco’s Tales series through written analyses and streamed playthroughs of a wide range of the Tales games on With a Terrible Fate’s Twitch channel and YouTube channel.

I believe we all forge our own destiny. Fortune tellers often say that our destinies are already 99% decided, but the remaining 1% can be changed through a person’s effort.

—Harold D. Morrison, Tales of Phantasia

[The significance of the direction of time’s arrow] as a governing fact “making sense of the world” could only be deduced on teleological assumptions. If physics cannot determine which way up its own world ought to be regarded, there is not much hope of guidance from it as to ethical orientation. We trust to some inward sense of fitness when we orient the physical world with the future on top, and likewise we must trust to some inner monitor when we orient the spiritual world with the good on top.

—Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World, pp. 338-339

A character I’d forgotten taught me what it takes to act when the world has forgotten you.

(Spoilers for Tales of Phantasia, Tales of Symphonia, and Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World.)

Chester Burklight is easy to forget in Tales of Phantasia because he’s written out of his own story. After a disciple of the wicked sorcerer Dhaos razes Chester and Cress’ hometown to the ground, kills their family, and revives Dhaos, Chester shields his friends from one of Dhaos’ attacks while the friendly mage Trinicus D. Morrison sends everyone but Chester back in time to learn how to stop Dhaos’ rampage. The consequence is that Cress makes new friends, works through his trauma, and becomes a hero in the war against Dhaos 100 years in the past—only to then chase Dhaos back to the moment when he attacked Chester in the present, defeating him with the power they lacked before their journey into the past.

Cress and his new party return to Chester and Dhaos moments after being sent back in time, fresh off of an entire war they waged 100 years in the past.

From Chester’s perspective, his best friend vanishes in what could very well be Chester’s dying moment, only to reappear an instant later with the fortitude and sense of purpose that Chester had just lost at the hands of Dhaos. And from the player’s perspective, as we follow Cress Albane into the past, the story of Tales of Phantasia quickly turns Chester into a footnote. In a 50-hour game, Chester has only 123 lines of dialogue—well under half the average of 303 lines per party member, and easily the lowest number of lines of any mandatory party member (second only to the optional Suzu, who sports 30 lines).[1] It’s easy to suppose that characters that don’t get much time in their own stories are somehow being done an injustice by the storyteller (“That character was robbed by only arriving in the final third of that game!”), but many stories teach us lessons that can only be expressed by marginalized characters. When I replayed Tales of Phantasia last year, one of its final shots led me to consider Chester as one of those characters:

The party prepares to return to their native times, with Chester facing away from the group.

After reuniting with Cress and following the rest of the party 50 years into the future to stop Dhaos once and for all, Chester faces away from the rest of the party as they say their goodbyes, as if to indicate the unbridgeable distance between their story and his. That’s not to say Chester has abandoned his friends: rather, what makes him so admirable is that he finds the resolve to support them and become the man he wants to be despite that unbridgeable distance. He is not only a literal archer but also a symbolic one: like the arrow of time, progressing inexorably in one direction, he gains the quiet wisdom of how to march on and make choices for himself even when his friends travel in all directions across time, gaining experience and understanding that will always elude him.

I want to pay tribute to this forgotten character from the source code of Namco’s Tales series. Almost 30 years ago, Tales of Phantasia set the standard for compelling character portraits illustrated through absence rather than presence, a standard that ripples through Tales games to this day. First, I’ll analyze Chester Burklight as a model for how we can make the impact we want in full awareness that we’ll never have enough context to fully understand our place in the world. Then, I’ll show how this model gives us a new way of unifying the “Aselia games”—the Phantasia, Symphonia, and Dawn of the New World trilogy—as three meditations on taking morally motivated leaps of faith in the absence of sufficient context for making sense of our actions’ impacts on the world.[2] Ultimately, we’ll see that Chester, in just 123 lines of dialogue, teaches us how to read out-of-focus characters, how to will ourselves out of inertia and into action, and even how to make sense of the “right” order in which to play the games of the Tales series.

Chester Burklight Lives His Life as a Sidequest

Chester begins Tales of Phantasia as one of the two major heroes in the story’s inciting incident, yet his development through the story is entirely optional.

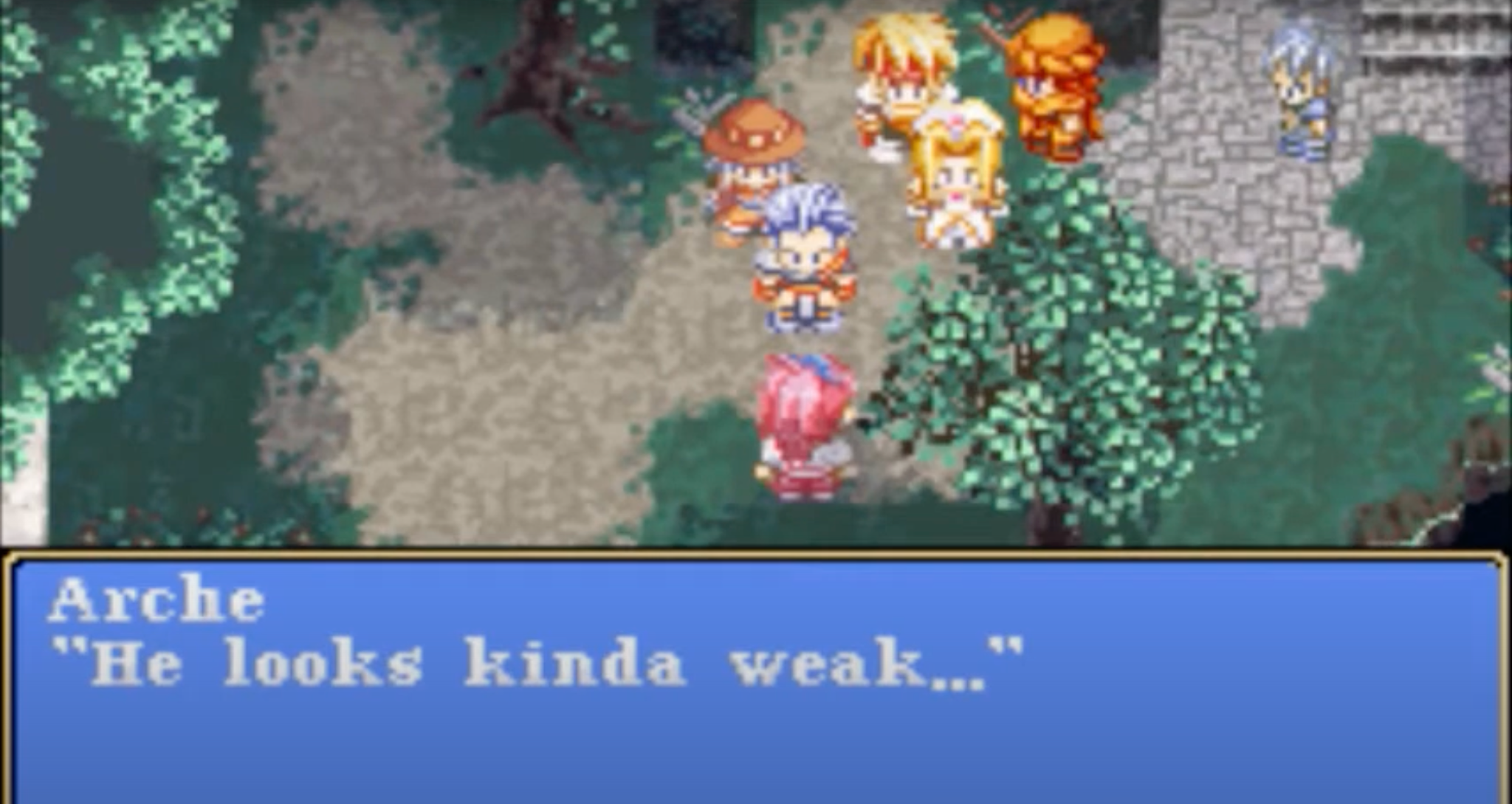

Arche assesses Chester’s fitness as they prepare to chase Dhaos into the future together.

After Cress and the other time-traveling heroes rejoin Chester in the present, Arche is quick to note that “[h]e looks kinda weak” and will have to “try to keep up” with the rest of them. This is true in more ways than one. Mechanically, Cress and his friends have advanced roughly 30 levels in experience ahead of Chester during their time in the past, rendering him virtually useless in combat alongside them. Emotionally, Cress has had the support of Mint, Arche, and Claus in processing the loss of his family and the pain Dhaos has caused to so many. Moreover, Cress has the opportunity to experience a deep catharsis over the loss of his family by learning about the schemes of Dhaos and the loss of mana in the world and taking up arms against Dhaos in the War of Valhalla, effectively stepping into his own family heritage to begin the battle against Dhaos which his father passed on to him in the present day. Chester, meanwhile, has no role in the lineage of heroes who opposed Dhaos in ancient times, and therefore has no way of coming to terms with the death of his family as part of some grander heritage to which he belongs. The most he can manage by way of coping with his loss is to sacrifice himself for the sake of his remaining friends, but he survives Dhaos’ blast, left only with a deep loss and no means of processing it. Chester’s weakness is a multidimensional prison of survivor’s guilt: he endured in the present when his sister, Ami, was killed and his friends were drawn away from him, into their own pasts. His only family member’s death and his own survival are both fluke accidents of collateral damage, and the one friend in whom he could previously confide has been so extensively submerged in his family history that he is now too far out of phase to help Chester process his pain.

Moments after Morrison passes their family heritage on to Cress and Mint, Chester sacrifices himself to take a blow from Dhaos in their stead.

In Tales of Phantasia, time travel represents how we make sense of our place in the world nonlinearly. We live our lives across a single trajectory of time, but the question of our identity and life projects often criss-cross into the past, the future, and a range of counterfactual timelines. To defeat a villain who, we’ll see, doesn’t care about time at all, our heroes need an encyclopedic, four-dimensional understanding of the world: rather than simply traveling across a spatial world map as a party would in another JRPG, they traverse a spatiotemporal map to understand the impact Dhaos is having in three distinct ages and how they can guarantee that their actions will have the desired effect in killing him and saving Aselia, the world of Tales of Phantasia.

- Cress and Mint learn about the actions their ancestors took against Dhaos and why they were insufficient.

- Cress masters the techniques of past empires to learn techniques that distort the fabric of space-time.

- Arche comes to understand Dhaos’ cruelty when she is possessed by the departed spirit of her friend, Rhea, who was killed at the hands of Dhaos’ minions.

- Claus bonds with the world itself by forming pacts with the Spirits who embody the elements supported by mana, which Dhaos is imperiling.

In effect, Cress and his friends are able to get the better of Dhaos by gaining enough context from across history to turn Dhaos’ atemporal assaults on the Aselia into historically grounded narratives. In the past, they participate in a historical war with the help of the divine horse Pegasus to overcome Dhaos’ armies and defeat him in his castle; in the present, they use Mint’s healing skills, bolstered by the support of a Unicorn, Claus’ summoning abilities, and the magical knowledge Arche has gleaned from spellbooks around the world (including Indignation, the heritage of Edward D. Morrison in the past) to overwhelm him at the same moment that Chester had previously been powerless.

When the party confronts Dhaos in his castle 100 years in the past, Dhaos has no interest in fighting them.

When Dhaos (chronologically) first meets the party 100 years in the past, he is explicitly disinterested in them. He says that he has “no reason” to fight them because, as we later learn (150 years later!), he is only interested in taking Aselia’s mana for the sake of revitalizing his own dying world, Derris-Kharlan.[3] For this reason, he is only invested in destroying those enterprises that compete for mana, such as magitechnology, rather than interfering in any particular events of world history. In the same way that Dhaos’ ultimate castle is hidden outside of the normal flow of time, Dhaos himself is aiming at something beyond the ordinary flow of time: he doesn’t care about interjecting himself in the timeline’s series of causes and effects, but rather about annihilating a possibility from all states that obtain across time, regardless of cause and effect. This is why he’s happy to rely indiscriminately on possessed minions, like Demitel and Jahmir, to enact specific schemes that undermine Midgards and magitechnology while he personally stays above the historical minutiae. In the face of Dhaos’ temporal indifference, Cress and his friends leverage their four-dimensional education to enact a saga in which they defeat him as time-traveling heroes. As Cress says, even if Dhaos doesn’t have a reason to fight them, his actions have given everyone in the party reasons to fight him—and their journey across time and space has afforded them the unique understanding and ability to move beyond all of Dhaos’ lackeys, find Dhaos himself, and drag him down into the minutiae of historical events to defeat him. By the time they return to Chester, they have already become legendary heroes, reshaping history in their image.

Chester’s location throughout the party’s journey in the past: fallen, on the ground of the Catacombs, clinging to life in the present.

Chester isn’t a part of that history. While his friends have gained a robust understanding of time travel, the wars of ancient kingdoms, international conflicts, and Dhaos’ schemes, he has quite literally stayed in one place—the Catacombs—and can only move forward from there. Seen in this light, against the backdrop of Dhao’s atemporal scheme and his friends’ time-traveling heroism, Chester can be read not just as a literal archer, but also as a symbol for the arrow of time: our experience of time as necessarily having a singular, irreversible direction from the past toward the future. Time’s arrow was first introduced almost 100 years ago by the astrophysicist Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, who presented it as part of a seeming paradox: whereas time seems to have this necessary directionality, there doesn’t appear to be anything essentially “one-way” about fundamental physics.

In the four-dimensional world […] the events past and future lie spread out before us as in a map. The events are there in their proper spatial and temporal relation […]. We see in the map the path from past to future or from future to past; but there is no signboard to indicate that it is a one-way street. […] I shall use the phrase “time’s arrow” to express this one-way property of time which has no analogue in space. It is a singularly interesting property from a philosophical standpoint. We must note that — (1) It is vividly recognized by consciousness. (2) It is equally insisted on by our reasoning faculty, which tells us that a reversal of the arrow would render the external world nonsensical. (3) It makes no appearance in physical science except in the study of organization of a number of individuals. Here the arrow indicates the direction of progressive increase of the random element.

—Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World, pp. 68-69

Cress, Mint, Ache, and Claus traverse this spacetime map in any number of ways to make sense of their relationships and create a narrative of their progress against Dhaos. Mint’s revival of the World Tree Yggdrasil in an age before her mother existed “render[s] the external world nonsensical,” but it allows her to make sense of the healer’s mantle which her mother passed onto her without ever explaining, using that understanding to heal the Great Tree that makes healing skills possible in the first place. Cause and effect don’t retread each other’s steps like this, but this is often how we make sense of our place in a world where actual and possible events touch us in the past, present, and future. We imagine our way through tautologies to justify our actions based on how those actions established the legacies into which we were born; the accomplishments of our future selves motivate us to shape our current identity to conform with that future.

Cress, Mint, Claus, and Arche time-travel back to the present to face Dhaos again after their war in the past.

This is what allows Tales of Phantasia to be an effortlessly straightforward narrative despite its timeline being convoluted by time travel: through our heroes’ actions, space and time are made to conform to their own character development, telling a story that condenses the chaos of war into a highly ordered journey that helps them make peace with their place in the world and channel that world’s energy into the intention of a Mana Seed—progressing from chaos to order in the way that time’s arrow seemingly won’t allow. A map of space-time is oriented relative to the perspective from which we experience the present moment, and Morrison’s act of time-travel magic in the Catacombs reconfigures our reference frame, as players experiencing the story, from one focused on Dhaos in the very first scenes of the game to one focused on Cress and Mint. But Chester isn’t a part of this reorganization of energy. By the time the party returns to him in the present, the narrative context of their struggle against Dhaos has been solidified without him. All that he can do is continue moving forward as a part of their story, and the only space in which he can enact his own story is the margin, moving according to a law that doesn’t apply to the rest of the party.

Chester explains his method of coping with trauma to Cress during a night at an inn.

Once Chester rejoins the party and they march on from the present to the future in pursuit of Dhaos, he diligently focuses on honing his skills with the bow and arrow in the face of Arche’s criticism. As players, we have the opportunity to witness two of these training sessions, both of which are optional: in the dead of night while the other party members are resting and dreaming at inns, Chester takes up arms against a dummy outside. Mechanically, these training sessions show Chester’s resolve to pull his weight in battle: a player would never rotate Chester into her battle party when he was at a 30-level deficit, and these sequences allow him to actually claw back experience points, rising to a level commensurate with the group average. He gains all this experience entirely through his own agency, training in cutscenes that don’t depend on the player’s influence and actions—in stark contrast to the real-time battles from which party members’ experience points typically derive. Emotionally, these sessions also cast a light on what it takes for time’s arrow to process his trauma in a world that has moved beyond him. He can only make this kind of progress on himself in optional windows beyond the scope of the main narrative the rest of the party has constructed—and, in fact, we only get the chance to witness Chester at his craft when Cress and Arche peek in on his training, so it may well be the case that he trains during other nights without any witnesses, fully beyond the view of the narrative and its audience. And this progress on himself is the only option Chester has available to make sense of his deepest wounds when he’s fallen out of phase with his entire support system. When Cress finds Chester training outside, Chester confides in him that he feels “the need to catch up” with Cress because Cress grew stronger than him “while living in a different timeframe,” after a childhood in which they always supported each other by training together. He then immediately shares with Cress that he’s tormented by dreams of those who were slaughtered in their hometown, confessing that training is all that can give him “a measure of peace.” With his mind on those victims, including his sister, he quietly, finally, tells Cress: “Cress, did you know? Ami, she liked you…”

Cress stands silent after Chester tells him that his murdered sister, Ami, liked him.

During this exchange, Cress says all of two words to Chester, mostly standing in silence. That silence is exactly why Chester must train like this: the friend to whom he could once best relate has now moved beyond him; the genocide that haunts Chester is now ancient history for Cress, who’s made new friends, become a war hero, and defeated Dhaos twice since then. Chester’s raw anger over the genocide of Toltus calls to mind the righteous anger with which Cress helped the spirit of Rhea, possessing Arche, exact vengeance on Demitel for razing her town, a cathartic opportunity for Cress to work through the loss of his own hometown. Cress had the privilege of processing his indignation 150 years earlier in a scenario that also helped him make sense of the bigger picture behind Dhaos’ seemingly senseless violence; he may have been able to travel back in time, but he can’t travel back to his raw, unprocessed emotional state in order to empathize with Chester.

When our heroes rest, their minds wander into dreams that relocate them to those moments in their lives they need to work through. For Cress, the legendary time-traveler, those dreams take him back to his father’s dojo, where his recollection allows him to internalize and learn the secret technique of his clan, Dark Blade. His journeys through time have made it possible for him to draw new power out of his past traumas, learning lessons rather than suffering; as players, we experience these dreams as a kind of reward, further developing our hero with an advanced combat ability. But we never get the chance to see Chester’s nightmares: for him, dreams are only the past’s way of haunting him and spurring his arrow to better strive toward the future goals he believes in. Cress barely speaks to Chester here because Cress has vanished into a context in which Chester cannot share, taking the player with him; the two boys are too far apart now to make sense of what it means to them that Chester’s murdered sister liked Cress, and so the statement simply hangs heavy in the air, unaddressed, over Chester’s continued training.

Chester expresses his pain to Arche during the second scene of his training.

Arche betrays the party’s misconception of Chester when she stumbles upon his training, hears him expressing his frustration that Dhaos robbed him of the opportunity to avenge his sister, and then asks, “Isn’t that the same for Cress? I’m not saying you should forget about your sister. But your frustration and impatience is too obvious. Looking at you… I can’t even breathe.” What Arche perceives as suffocating impatience is the same thing that separates Chester from Cress. Chester has lost everyone in his home as well as the understanding of the only friend who could grasp that loss, and so all he can rely on to process that grief is his own actions—actions which he can aim at his principles of justice, but actions which can never fell the man who killed his sister, Mars Uldole, since Dhaos slew him first. That kind of intercepted causal chain—where Dhaos killed the murderer of Chester’s family and robbed him of revenge—doesn’t mean much to a time-traveler like Cress, who has come to understand both Dhaos’ schemes and his own family’s legacy in holistic, non-causal ways. For Chester, the potential to make the right kind of causal impact is everything. “Impatience” is the perspective of someone with one, finite path on which to make his mark on the world, an impatience which Arche—a half-elf with a lifespan of hundreds of years—won’t understand until her hero’s journey is over, at which point she’ll need to lean on that archer whose arrows she couldn’t understand at the time.

Arsia gives Chester his strongest weapon, the fully enhanced Elven Bow, as a gesture of gratitude for the party’s efforts in reuniting her with Brambert.

The story of Chester’s strongest bow, the Elven Bow, highlights that his identity as the arrow of time is a burden which must be borne with neither myopia nor resentment: the context required to fully make sense of his actions might be sequestered beyond his reach, but he is still bound to that context, and he must trust those who do have access to that context. Chester’s original hunting bow—the tool with which he acts upon the world—is lost to time along with Cress and Mint when it gets caught in Trinicus D. Morrison’s time-travel magic. In another sidequest—one of the game’s longest, spanning a full 150 years—Cress, Mint, Arche, and Claus work together to repair the bow for Chester. Like the rest of the game, the sidequest quickly turns its focus away from Chester per se as the party finds itself in the middle of a fraught romance between Brambert, leader of the isolationist Elven Colony, and Arsia, a half-elf living quietly exiled in a mansion just outside the Colony. In an effort to rekindle Brambert’s affections, Arsia uses her magic to turn Arche to stone, using her as collateral to force the party to bring Brambert to him; acknowledging that the schism between elves and half-elves is too deep to ever allow the elven leader to live his life with a half-elf, Brambert nonetheless allows Arsia to turn him into a statue in Arsia’s place, sacrificing his autonomy to become a literal object of her affection. 150 years later, the party, now with Chester in tow, finds that Arsia turned herself into a statue in Brambert’s place following his gesture of self-sacrifice. Once Brambert finally acknowledges that his love for Arsia is more important to him than his sense of duty to the elves, the curse Arsia placed upon herself is lifted: she is freed from her stone prison, and the two resolve to live together, offering Chester that original, broken bow which Arsia has refashioned to be more powerful than ever.

Their effort to mend the bow shows that Cress and Mint don’t deserve resentment for shifting out of phase with Chester: even when his friends fall into a different time and lose the ability to intimately relate to him, they do what they can to support and honor him. And the conflict between elves and half-elves at the heart of this sidequest’s dialectic shows that Chester still, crucially, has the ability to influence those people and cultures he touches even if he must stand ontologically outside of them. Chester is a human and never journeyed to the past: he doesn’t know Arsia and Brambert, and he has scarcely any frame of reference for grasping their interracial conflict. Yet the central mechanic of the quest, Aria turning people into statues, strongly correlates with the thematic meaning of Chester as time’s arrow. Under what conditions would you resolve to fix yourself, statuesque, in space, progressing through time with no further ability to chart your own future: accepting that you will be blind to the activity of the world around you, all for the sake of one decision it was within your power to make? Arche answers this question when she pushes Mint out of the way of Arsia’s blast and becomes a statue as collateral in her place; Brambert answers it when he takes Arche’s place and resigns himself to exist forever as a decoration in Arsia’s mansion; Arsia answers it when she makes herself into a statue, removing herself from the world until and unless her beloved acknowledges her without qualification.

Arche takes Brambert to task for living in a purgatory of guilt over his mixed-race love with Arsia rather than embracing his true feelings, prompting him to confess his love and unwittingly lift Arsia’s self-imposed curse.

Even though that influence of Chester isn’t explicitly acknowledged in this sidequest, I think the party feels it, particularly Arche. Only after witnessing Chester’s resolve to train through the night in a full embodiment of his impassioned frustration, and only after seeing the color of that same straightforward resolve in Arsia making herself a statue, is Arche ready to take to task the leader of the elves—the figurehead of the race who persecuted her and forbade her from living with her own mother—for his lack of honesty about his feelings. In the face of Brambert’s hand-wringing over the uncertain crossroads of future elf/half-elf relations and the guilt he feels over his role in that crossroads, Arche channels Chester’s ethos when she speaks up: “I think how a person feels is more important… More important than whether they’re elf or a half-elf! […] Your indecisive attitude makes me madder than anything!” Chester has taught Arche that it does violence to oneself and one’s actions to reach for a complete understanding of the world when that understanding simply isn’t possible: the future-timeline Brambert couldn’t know with certainty how his choices would shape the future relations of elves with half-elves any more than he could have known this during his 150 years as a statue. The more painful and authentic option is to act according to one’s most deeply held values in full knowledge that one can’t possibly know all the potential factors or outcomes interrelated with one’s actions: to simply, decisively, voice one’s feelings, as Chester did during his training and as Brambert ultimately does for Arsia. I think that this insight is ultimately what bonds Arche with Chester, a bond on account of which she turns to him—and turns him around to face the group as a whole—in their final goodbye, when Arche must find a way to also live as time’s arrow for 100 years: marching forward from her original timeframe, beyond the lifespan of Claus, until she can catch up with the rest of her friends in their native eras.

Chester and Arche say goodbye at the end of Tales of Phantasia, until they meet again 100 years later (from Arche’s perspective).

Though the rest of the party can’t bridge the gap between their history and Chester’s, they can witness and acknowledge the strides he takes on his own to square his journey with theirs. In yet another optional scene, the party is invited to use the Ninja Village’s hot spring after freeing Suzu’s parents from the yoke of Dhaos. While the legacy of hot springs in the Tales series has mostly been one of comedy (and these very first scenes are no exception to that rule), there’s also a special kind of symbolism in these scenes which we ought to be alive to: stripped of their outfits (outfits that often project specific aspects of characters’ roles, histories, and personalities in Tales games), characters of the same sex are placed in a social scenario that forces a certain level of interpersonal intimacy: they witness each other immediately in a more vulnerable light than is possible in virtually any other area of the world. So, even if Cress has lost the common language with which to help Chester work through his trauma, he can sit in the hot spring with him and witness how vividly his resolve to train has changed the nature of his body—and he can acknowledge that effort before Chester, despite being unable to discuss the emotional content underlying that training. Is it any wonder, then—sexual attraction notwithstanding!—that Arche would want to peek over the fence at the body of someone whose training symbolizes such a personally salient form of resolve for her?

At the Ninja Village’s hot spring, Cress acknowledges how Chester’s training has changed him.

Fully developed, Chester ends up having some of the strongest attacks in Tales of Phantasia, striking enemies from afar with everything from one giant arrow to a barrage of smaller homing arrows. Like him, those arrows decisively and impatiently advance, laying into enemies much more efficiently than, say, the Spirits or spells that suspend the entire battle’s progress in order to take effect, radically lengthening the duration of combat. You’d be forgiven for not taking advantage of his power, or even for forgetting about him entirely: in a deep sense, Tales of Phantasia isn’t his story. But the remarkable aspect of Chester as a symbol, as time’s arrow, is that this dismissal is the source of his strength. By resolving to march forward according to his inner sense of discipline and justice regardless of how isolated he may feel from the rest of the world, he becomes a force of nature that seeps out into all the context surrounding him, inspiring and orienting his companions even when they lack the standing to name his influence on them. It’s in this sense that he embodies the ethos of this study’s epigraphs, in which Morrison’s descendant reflects on the role of personal effort in the face of destiny and Eddington reflects on the role that remains for the mystical in a physical world: by taking stock of his lot in life and diligently making whatever effort he can, Chester not only chooses his own linear path through the world, but also orients the ethical stratum of his world according to that path.

Reading Phantasia, Symphonia, and Dawn of the New World through Time’s Arrow

Over the years, I’ve struggled to put my finger on what element or theme unifies Tales of Phantasia, Tales of Symphonia, and Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World as a coherent trilogy, beyond the fact that they all take place in the same fictional world.[4] In the time I’ve dedicated to Chester, I’ve come to think that might be because they’re better unified by an absence than a presence, along with a certain praxis for coping with that absence.

In order of original release: Tales of Phantasia (1995), Tales of Symphonia (2003), and Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World (2008).

I want to share with you a picture of how we can read these three games as different applications of the time’s arrow model we’ve drawn from our character study of Chester. Part of the power of this model, I suggest, is that it furnishes us with a lens to see virtually every aspect of a story—and of our real place in the world—differently. We can follow Chester’s lead by taking a leap of faith: acting with a disciplined commitment to our beliefs while fully aware that we can’t be certain of how our actions connect with the world, other people, or even ourselves. I’ll illustrate Phantasia as an application of this perspective to an antagonist, Symphonia as an application to a world, and Dawn of the New World as an application to a protagonist.

Tales of Phantasia: Separating Means from Ends

In Dhaos’ Castle, a stone tablet offers guidance to one of the game’s final puzzles, in which the party must step on pressure plates throughout the floor in a certain order: “Start from the end.” The puzzle is a microcosm of the party’s relationship with Dhaos: they chase him back and forth throughout time and space, yet it’s only at the end of their confrontation with him that they finally learn what his goal is.

A stone tablet offers guidance for one of the final puzzles in Dhaos’ castle.

As we considered above, Dhaos isn’t invested in the events of Aselia per se: he’s only concerned with aggregating enough mana to extract a Mana Seed from Yggdrasil and rejuvenate his dying world, Derris-Kharlan. The party soldiers onward in their quest to defeat Dhaos primarily through a combination of their own family history in a multigenerational battle against him—as recounted in the book which Trinicus D. Morrison gave Cress and Mint before sending them through time, orienting their journey—and the scenes of violence enacted by his minions, brainwashed to act as Dhaos’ pawns within Aselian history. Mint succinctly captures their perspective when the Spirit Origin, Source of All Things, provocatively asks the party whether they really know anything about what Dhaos is or why he is in Aselia: “True,” she says, “we really don’t know much about him. But… Do you know how many people have suffered because of him?” Our heroes travel through time counteracting the consequences of Dhaos’ actions even as they remain unaware of the purpose those actions serve. And then, at the last, something remarkable happens for the first entry in a long-running JRPG series, setting the tone for the rich complexity of the many conflicts we’d see in later Tales games: our heroes fulfill their villain’s wish, sending his dying world a Mana Seed—at the cost of Aselia’s own mana supply—for the sake of those same people whom Dhaos had championed all along.

The heroes send a Mana Seed to Derris-Kharlan for the sake of Dhaos’ people, the final moment in Tales of Phantasia before its end credits.

This time-bending battle against Dhaos is a macrocosm of Chester’s discipline as time’s arrow. As Chester trusts in the practical sufficiency of his actions despite lacking the context to make sense of his own life, so too must the party as a whole trust in the moral sufficiency of their actions despite lacking the context to make sense of Dhaos’ identity and goals. Where Chester diligently hones his agency in the isolation of training, the party charts its irreversible pursuit of Dhaos by focusing solely on the vignettes of suffering set out before them: killing Demitel to settle the score for his decimation of Hamel; liberating Prince Laird from the influence of Jahmir; ending a war to minimize Aselian casualties against a monster army. In the one case where the party seriously questions Dhaos’ motives, they quickly retreat from the question like Cress retreated from conversation with Chester during Chester’s nighttime training. On the cusp of the War of Valhalla, Arche muses that Dhaos may have some hidden agenda since he’s primarily targeting Midgards while sparing other regions of Aselia; after Edward D. Morrison sacrifices himself to save a child hostage from Justona, one of Dhaos’ minions, Cress rebukes Arche: “Do you still have doubts about Dhaos now? […] You saw it, didn’t you!? He’ll stop at nothing to kill us!” “I know,” Arche replies, “I’ll keep my mouth shut from now on”—and she does, refocusing their efforts on the suffering they can address rather than those agendas they can’t understand.

Arche decides to stay silent about Dhaos’ broader motives after confronting another scene of the immediate suffering a minion of his caused.

After the final battles—witnessing the sheer force of will with which Dhaos invokes the prayers and gods of his world more than once to persist against them in multiple forms—the party achieves something beautiful: they condemn Dhaos’ means while validating and bringing about his end. Claus captures this perspective crisply when the party finally stands before Yggdrasil and decides to send a Mana Seed to Derris-Kharlan: Dhaos, he reminds everyone, “slaughtered countless people. And we’ve made it this far by believing in what we were doing”; but, he adds, sending Derris-Kharlan a Mana Seed is “the least we could do… after his lonely struggle for what he believed was right”—a struggle, perhaps, just as lonely as Chester’s. While the party’s only recourse for morally correcting Dhaos was killing him and his minions, their adherence to their “inward sense of fitness” throughout their journey allows them to remain focused on the mitigation of suffering, rather than on the categorical villainizing of a man. They couldn’t speak to him on his own terms any more than Cress could with Chester, but they can wordlessly empower his people with a gift beyond their world, just as Cress empowered Chester with the Elven Bow. Ironically, Dhaos’ sequestration of himself beyond the realm of historical cause and effect makes it easier for our heroes to denounce his evil actions without denouncing his reasons, and it also makes it easier for them to put his actions on a par with other sources of suffering in the world: it’s reasonable to suppose that it’s a kindness to Aselia and Derris-Kharlan alike for Yggdrasil to send the comet a Mana Seed since this also eliminates the possibility of magitechnology on Aselia—the cataclysmic sorts of weapons that Midgards unleashed against Dhaos’ forces in the War of Valhalla, not dissimilar to the terrible force of nuclear warfare.

Tales of Symphonia: Marching through Spider Webs

Lloyd Irving may be the most consistent protagonist in a Tales story. He finds himself in a story where each of his actions ripples out to shift worlds and relationships that are entirely invisible to him, as if he were walking along a vast spider web and only very gradually coming to see its constitutive threads as he went; yet through it all, he steadfastly orients himself with his inner sense of justice.

Lloyd expresses his renewed resolve to save everyone moments after learning that Kratos is his father.

I wrote previously about the phenomenology of gradually realizing, as a player, that the world of Tales of Symphonia is much larger than the quest that had been framed for us: first expanding from Sylvarant into Tethe’alla, then into Derris-Kharlan, then into the deep past of the Kharlan War and its aftermath. A corollary is that our party of heroes constantly has to evaluate the fit between their principles and their conception of the world as they learn more about how expansive and interconnected that world is. Can their Journey of Regeneration save Colette? Can they find a way to save Colette, Sylvarant, and Tethe’alla? Can they restore the natural order of the universe? At each juncture, Lloyd applies the same principles: that every life has value; that people have a duty to save those whom they can save; that people must constantly act, acknowledge their mistakes, and atone. His growth over the course of the story doesn’t center on his developing those principles, but rather on his recognizing context he had overlooked and squaring his principles with that new context:

- He relies on the narrative of Colette as a holy, chosen savior to motivate the righteousness of their journey, only to realize at the Tower of Salvation that she had been quietly preparing to sacrifice her life at the end of the journey, with Lloyd never realizing her burden despite relying on her. This prompts Lloyd to take charge of leading the group out of Sylvarant and into Tethe’alla in pursuit of a way to save her and atone for not seeing her suffering earlier. As he tells Sheena, “I’m going to fulfill my role. I’m not going to let Colette bear the burden all by herself anymore.”

- After stumbling upon the fact that Sylvarant and Tethe’alla are held together in interdependence by links between the mana of their Summon Spirits, Lloyd promptly decides that the best course of action is to “separate the two worlds” by severing those links, putatively saving everyone from cycles of suffering. When the last link is severed and the party realizes they’ve only managed to germinate the Great Seed in a corrupted form that threatens to destroy both worlds, Lloyd takes in this new information and quickly fashions a plan to fix his error and restabilize the worlds by calming the Great Seed with the Renegades’ Mana Cannon.

- He supports Genis in helping out one of Genis’ only friends—Marble, an old woman imprisoned by the Desians at Iselia’s Human Ranch—only to inadvertently set in motion a multigenerational chain of torture inflicted upon Marble’s lineage by the Desians: they first turn Marble into a monster and lead her to kill herself (an effort, on Marble’s part, to protect Genis and Lloyd from the Desians), and they later reveal to her granddaughter, Chocolat, that Lloyd “killed” Marble in order to break her spirit and turn her against Lloyd. Rather than condemning himself or writing the family off, Lloyd goes out of his way to find and rescue Chocolat from the Desians: fully aware that he hates him, but resolving, as he later tells Presea, that “[w]hether or not you’re forgiven isn’t important. It’s the effort that matters.”

Lloyd saves Chocolat without attempting to resolve her hatred of him.

That effort which Lloyd doggedly and consistently invests in embodying his values vividly echoes Chester’s perspective, propelling himself with the inertia of his own actions even as the world’s structure keeps the consequences of his actions “out of phase” with him, unknowable until far after he’s already acted. But Lloyd is unlike Chester because he is far from alone in these actions: part of the magic of Tales of Symphonia is watching Lloyd’s deep sense of virtue catalyze rich bonds between him and the eight other party members, who discover, adapt, and react to the unfolding world alongside Lloyd.

I think the model of time’s arrow helps us to see what makes the game symphonic, harmonizing Lloyd’s journey through physical worlds with his journey through relationships: although Lloyd has plenty of companions, his relationships with them are opaque in the same way his relationship with the physical worlds is. As I discussed in my study of Regal Bryant, the game features a sophisticated and invisible system for quantifying and comparing Lloyd’s relationships with other party members based on the player’s choices of whom to interact with and what to have Lloyd say in certain scenarios—some mandatory, and some optional. Further, Lloyd travels across the world alongside (and, later, in opposition to) his biological father before ever learning his identity, and he completes his entire journey with his mother’s spirit on his hand, dormant until the very last moments of the game. Sometimes, Lloyd’s interactions strengthen his bonds to the point that a character ends up intervening on Lloyd’s behalf where he or she wouldn’t otherwise (e.g., Kratos rejoining the party, a best friend standing up to Mithos on Lloyd’s behalf); at other times, the distance between Lloyd’s interactions with someone and the person’s background, unbeknownst to Lloyd, opens the door to betrayal (e.g., Zelos selling the party out to Cruxis, Governor-General Dorr misleading the party and undermining Palmacosta). In Tales of Symphonia, getting to know another person is functionally equivalent to exploring a world: their own personal history, beliefs, and desires are equally part of the spider web Lloyd is navigating, and he must equally trust in his own principles to have an authentic, if unpredictable, impact on his bonds with them.

If Kratos returns to help the party stop Mithos’ resurrection of Martel, Mithos calls it a second betrayal, whereas Kratos calls it an expression of regret that he couldn’t alter his old friend’s path in life.

The current state of the world in Tales of Symphonia, which Lloyd and his friends rectify, stands as a warning of what can happen if we allow ourselves to be ruled by the risk of betrayal borne by other people. As soon as there is contextual distance between ourselves and the other, it is possible for the other to break our trust—for a nameless human to cut down our sister in cold blood, as was the case for Mithos Yggdrasil (as it was for Chester Burklight, after him). In coping with this senseless tragedy without processing it, Mithos illustrates the suffocating loneliness that comes from corrupting the ethos of Cress and Chester in sequence: first trying to master all possible factors that could have been related to his personal tragedy, and then finding himself so isolated by that process that only a single, fruitless path remains available to him. Where Cress came to make sense of his parents’ murder by traversing space-time, mastering space-time, and understanding the mesh of historical factors that led his parents and Dhaos’ minions to that tragic meeting, Mithos tries to conquer Martel’s murder by controlling all possible aspects of existence that could possibly have contributed to her death. What Mithos masks behind the vision of “a world without discrimination” and an end to magitechnological warfare is really just a desperate struggle to turn his “dream of a world for my sister and me” into reality (using the cessation of magitechnology as an excuse to justify his selfish goal, rather than arriving at the cessation of magitechnology as a consequence of pursuing a selfless goal, as Cress and his friends did when they sent Derris-Kharlan the Mana Seed). The hampering of civilizations, the conversion of living beings into Exspheres, and the manipulation of bloodlines all serve the purpose of mastering the factors that led to her death: bending history so that her mana signature would persist in a host so that she never died, and eliminating both individual and societal variability so that conflict could never arise. When the world is only Mithos’ world, no one can betray him because there is no context beyond his own, no role for trust to play; when his sister is identical with that timeless context, not even existence itself could threaten her. Yet as we’ve seen, Tales of Symphonia teaches that relationships require a discrepancy in context: when our principles limit us to only those aspects of the world and people which we can directly access and understand, those principles wall us in, preventing us, by definition, from bonding with anyone beyond ourselves.

As Genis and Mithos become closer friends before Genis knows Mithos’ true identity, Mithos begs Genis not to betray him.

This is the way in which Mithos’ scheme perverts the symbology of time’s arrow, rendering him completely out of reach of everyone where Chester was only out of phase with his companions. Even when friends like Kratos genuinely try to correct him, Mithos only sees betrayal; when Martel herself wakes up and identifies herself as someone beyond Mithos’ conception of her, Mithos sees only rejection. In this light, I find Mithos’ time spent traveling with Lloyd’s party incognito especially heartbreaking. I think that he reaches out to Genis in hopes that someone beyond himself—”the first half-elf friend I’ve had that is near my age”—could come to empathize with him and endorse his same ideals, proving that he didn’t make himself an enemy of the world when he reshaped it. In skits with Genis during their time together, Mithos confesses that he “couldn’t forgive the humans who killed [his sister]” and asks, hopefully, “You understand my feelings, don’t you?” When they travel together to find a cure for Rain’s sickness atop the Fooji Mountains, he asks whether Genis would side with him or Lloyd if the two were to get into a fight; when Genis playfully picks Mithos, Mithos tells him that “I wish we could stay together forever.” And after Mithos saves the party from the Remote Human Ranch, Genis promises to help Mithos if he ever needs it; Mithos quietly, sadly, replies, “Please don’t betray me, Genis.” Mithos is the tragic paradox of a boy who wants to control everything but wants the kinship of someone beyond himself who can validate that control; when everyone refuses him, he’s left with a hollow gesture of resolve as his final words: “Farewell, my shadow. You, who stand at the end of the path I chose not to follow. I wanted my own world, so I don’t regret my choice. I would make the same choice all over again. I will continue to choose this path!” His is the resolve of Chester with no actual principles substantiating it: in the place of something like Lloyd’s justice, Mithos only marches forward for the sake of a formless oblivion. I think this hollowness inspires his singular suspicion—uttered in confidence to his “old friend,” Noishe—that “there’s no meaning to life.”

Lloyd literally and figuratively shatters the illusion in which Mithos imprisoned Genis and Raine in Welgaia.

In my character study of Regal Bryant, I analyzed the method by which characters in Tales of Symphonia (and Dawn of the New World) interpret their past in positive, motivational ways in order to have the impact they want on the world, honoring their history without being imprisoned by it. Our study of Chester as time’s arrow gives us another way to put this, from Lloyd’s perspective rather than the perspective of those he helps: as characters like Regal wrestle with their history and psychology, Lloyd enters the “world” of their identity and explores it while applying his simple, consistent principles to help them unlock new ways of seeing themselves, like Regal reinterpreting his sadness for Alicia as a symbol of Alicia’s importance to him. In this light, the final scenes in Welgaia where Lloyd liberates his friends from Mithos’ illusions is a microcosm of time’s arrow giving us the strength to embrace the world rather than shrinking from it: Mithos tries to crush Lloyd’s friends under the weight of every specific event, possibility, and judgment from across their history, like an illusory Mayor and mother’s rejection of Genis and Raine as having “no place in this world”; Lloyd cuts through this paralyzing morass of history with his same clear principles of justice—in Genis and Raine’s case, declaring that “People who can’t accept those who are different are the ones to blame.” Revisit these scenes and reflect on the sheer complexity of the illusions’ characters, backstory, and dramatization, compared with the short, incisive, idealistic interjections of Lloyd; within that contrast rests the heart of Tales of Symphonia.

Dawn of the New World: Humanity as an Intermediary

Chester experiences the deeply human loss of undergoing trauma and losing his means of processing it. Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World takes Chester’s symbolism as time’s arrow and rephrases it as a challenge: can the player convey humanity to someone who lacks any of the context necessary to be human?

Yuan, the guardian of Yggdrasil, asks Emil what he thinks of his own identity as the party finally comes to understand what’s been at stake throughout the plot of Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World.

Between monster companions, three mutually incompatible endings, a chapter-based story, and a postcard-like world map, there’s a wealth of unusual structural elements that make Dawn of the New World hard to square with the broader Tales series. I want to consider one way in which those elements come together to form a puzzle for the player, which can only be resolved by treating our avatar as we would Chester.

First, let’s get the game’s final scenario fresh in our minds. We ultimately learn that our avatar, Emil, is an artificially constructed personality housing the real Summon Spirit, Ratatosk, who is recovering his strength after being wounded by Richter. In order to re-seal the door in the primordial Ginnungagap between Aselia and Niflheim, the realm of demons, Emil tries to trick his friends into thinking that Ratatosk has taken over his body and is trying to kill them, so that they will fight back, wound him, and force him to return to his dormant core state, sealing him within the door as a kind of lock. The outcome of Emil’s gambit depends on the player’s choices.

We’re given control of Emil in a fight against Lloyd and Marta when he tries to trick them. If we go along with the game and defeat Lloyd and Marta, Emil mistakenly thinks he’s killed Marta, and he responds by desperately killing himself, sealing the door in a way that causes everyone lasting agony and leaving the world dependent on Derris-Kharlan’s foreign mana, which has caused so many wars and fractures in the natural order. However, if we let Emil lose against Lloyd and Marta, Marta recognizes his charade and prompts him to reach a different, better understanding with Ratatosk, at which point one of two things can happen: either (1) Emil and Ratatosk fully integrate with each other, combining Emil’s compassion with Ratatosk’s metaphysical authority, and team up with Richter to rewrite the universe’s laws, shielding humanity from demons without an ongoing dependency on mana, or (2) Ratatosk takes up this task with Richter and, at Richter’s request, gives Emil his own, separate human body in which to live out a life in Aselia with Marta and his friends. So, from Emil’s perspective, the three endings represent three distinct outcomes for a personality that was insubstantial to begin with: self-annihilation, integration with the parent identity, or full individuation, validated with the substance he’d never had.

The player is put in control of Emil, pretending to be Ratatosk, with Lloyd and Marta as “enemies” to defeat in the Ginnungagap.

So, here’s our puzzle. The difference between the player having access to the ending in which Emil integrates with Ratatosk and the ending in which he individuates from Ratatosk is in seemingly inconsequential decisions the player makes throughout the game: to access the ending in which he individuates, the player must have Emil not pledge his loyalty to “Lloyd the Great” at the beginning of the game under pressure from other townsfolk in Luin, during a time when Emil mistakenly believes that Lloyd killed his parents; she must make sure that he doesn’t backtrack a large number of times from the Triet Ruins before making it to the end and acquiring the Core of Centurion Ignis; she must make sure that he doesn’t stand idly by and get hit by a large number of lightning bolts in the Temple of Lightning before making it to the end and acquiring the Core of Centurion Tonitrus.[5] To give Emil the opportunity to individuate, then, the player must have him stride forth along the main story’s path with unyielding determination: holding fast to his beliefs about Lloyd in the face of peer pressure, and striding confidently into the Centurions’ resting places without flitting back and forth to other locations or loitering about with uncertainty. Yet for Emil to successfully individuate rather than annihilating himself, the player must also stop pushing Emil forward at exactly the right moment: she must know to let Marta and Lloyd win when Emil feigns possession as Ratatosk and attacks them, despite the game coding Marta and Lloyd as “enemies” for the player to defeat. So, what about this game makes it reasonable that the player would doggedly push Emil forward at every step in his journey except the last one, and what does that tell us about what it takes to give someone enough context to make them human?

Richter encourages Emil to fight for his values with his own strength during one of their optional adventures together.

The solution to this puzzle presents itself when we look again to Chester: as in the case of Tales of Phantasia and Chester, there’s a sense in which Dawn of the New World isn’t Emil’s story, despite being deeply concerned with him. Its main story isn’t catalyzed or anchored by Emil per se, but rather by the Summon Spirit Ratatosk trying to regain his strength to wipe out humanity, Richter acquiring the means to resurrect his friend Aster and kill Ratatosk, and the Vanguard terrorizing Tethe’allans in a misguided effort to earn Sylvaranti better treatment in the new world of Aselia. In contrast with this suite of agents, Emil is, as Tenebrae says, “a fabrication put together by Lord Ratatosk.” But regardless of his etiology, Emil has a special power, the game’s slogan (courtesy of Aster): he can use courage to turn dreams into reality. More concretely, Emil can make decisions to speak up, engage with others, and come to understand them; in doing so, he can share that courage with them, inspiring them to vocalize and justify their own desires, beliefs, and dreams. This is how I read Richter’s comment to Emil during the second of their optional adventures together, in which Emil unwittingly helps Richter acquire the Sacred Stone Richter intends to use to sacrifice his life and seal the door to Niflheim after getting his revenge on Ratatosk for killing Aster. When Emil unexpectedly encounters his uncle Alba on that journey and cowers in fear, Richter tells Emil that Emil has the power to change his relationship with Alba:

[Alba’s] actions mirror your own. You were afraid and retreated into your shell, so he did the same. […] “Courage is the magic that turns dreams into reality.” […] Courage is also what you need to break out of your shell. That’s how you got Marta to join you. She opened up to you because you risked your life to protect her.

We see this concept of people mirroring Emil and inheriting his courage, for instance, when Emil “give[s] [his] courage” to Marta by insisting that she owes it to herself to try speaking with her father, Brute, one more time during his Vanguard uprising, rather than preemptively giving up and resolving to do battle with him instead. She absorbs and internalizes his praxis in the way Arche does with Chester. With Marta, Richter, and even the heroes of Tales of Symphonia, Emil gains context for the world by surfacing their context: not passively witnessing them from afar, but consistently investigating them and encouraging them to account for themselves. And, crucially, because Emil is a construct outside of the actors motivating the game’s main plot, he has equal reason to engage people inside and outside of the main plot in this way. This is the solution to our puzzle: to understand Emil sufficiently to halt his gambit in the Ginnungagap and make possible his individuation, the player must have him stride forth along all possible paths in the story with unyielding determination, not just the main story. Perhaps this shouldn’t surprise us, either, in a story whose main elements come from optional content in its predecessor: from the demons we first discovered in the sidequest confronting the demon lords Mithos sealed away in a book, to the Summon Spirit of Heart whom Sheena can optionally will into existence with her love for Corrine and her friends, Dawn of the New World is centrally concerned with surfacing and squaring the least perceptible threads of context in Tales of Symphonia’s spider web.

Richter lets Emil know that helping him on his sidequests probably won’t help him better understand Ratatosk.

Dawn of the New World features unusually long, easy-to-miss sidequests threaded throughout its eight chapters that allow the player to exercise Emil’s single-minded focus on the background of the main story’s villains: Richter, Alice, and Decus. Beyond merely learning about Richter’s background, the player is able to properly ally Emil with Richter on three different occasions and travel as a two-person party to help Richter acquire the chain of items that ultimately give him access to the Sacred Stone. In the case of Alice and Decus, we get the opportunity to excavate their shared childhood history, which transforms them from comical sideshows into tragic, admirable, and deeply informative figures in the story. As we unearth the context of these villains, Emil doesn’t personally gain more context that would grant him identity where there was none (say, discovering a hidden history that he actually had as a human being, which proved that he was not a fabrication of Ratatosk), but he makes these characters’ own context accessible to others in a way that can change their conception of the world and their actions:

- Genis and Raine witness and come to admire Alice’s unapologetic “self-confidence” despite the prejudice and persecution she’s faced as a half-elf and orphan, seeing her as a model for the half-elf race moving beyond its tortured history.

- The party learns what it actually means for demons to walk the earth from Decus’ explanation of Alice making a pact with a lesser demon to control monsters and save Decus’ life, and Marta learns from Decus’ example that it’s possible to freely surrender ownership of your life to someone else for good reasons—say, love—as Decus did when he “decided to give [his life] to [Alice]” to honor what she did for him in childhood.

- As players, we learn from Emil joining up and sharing adventures with his enemy, Richter, that labels of “companion” and “enemy” are fungible in this world; and from (1) Richter, (2) Alice, and (3) Decus together, we learn that (1) we can change the people around us through our actions, (2) we must act of our own volition rather than relying on others, and (3) we can choose whom or what we live for.

Decus explains his history with Alice to the party in Hima, giving them their only model of demons’ influence on the world in the process.

The last of these three points shows us how Emil’s journey through others’ lives teaches players the right choice to make on Emil’s behalf at the end, even as it cuts against the grain of every video-game experience that’s taught them they must kill their enemies. In order to earn the full individuation and humanity of Emil, the player must make a metafictional leap of faith, on a par with the moral leaps of faith we’ve taken with respect to Dhaos’ goals and Lloyd’s sense of justice: we must trust that Emil, our avatar—this tool that relies on our actions for its own agency in the game—has value independent of our input, and we must put our controller down. In effect, we must turn Emil into something other than an avatar in the same way he turns Richter into something other than an enemy during their sidequests, allowing him to pursue his own agenda without our context—the same affordance Cress and his friends gave Chester.

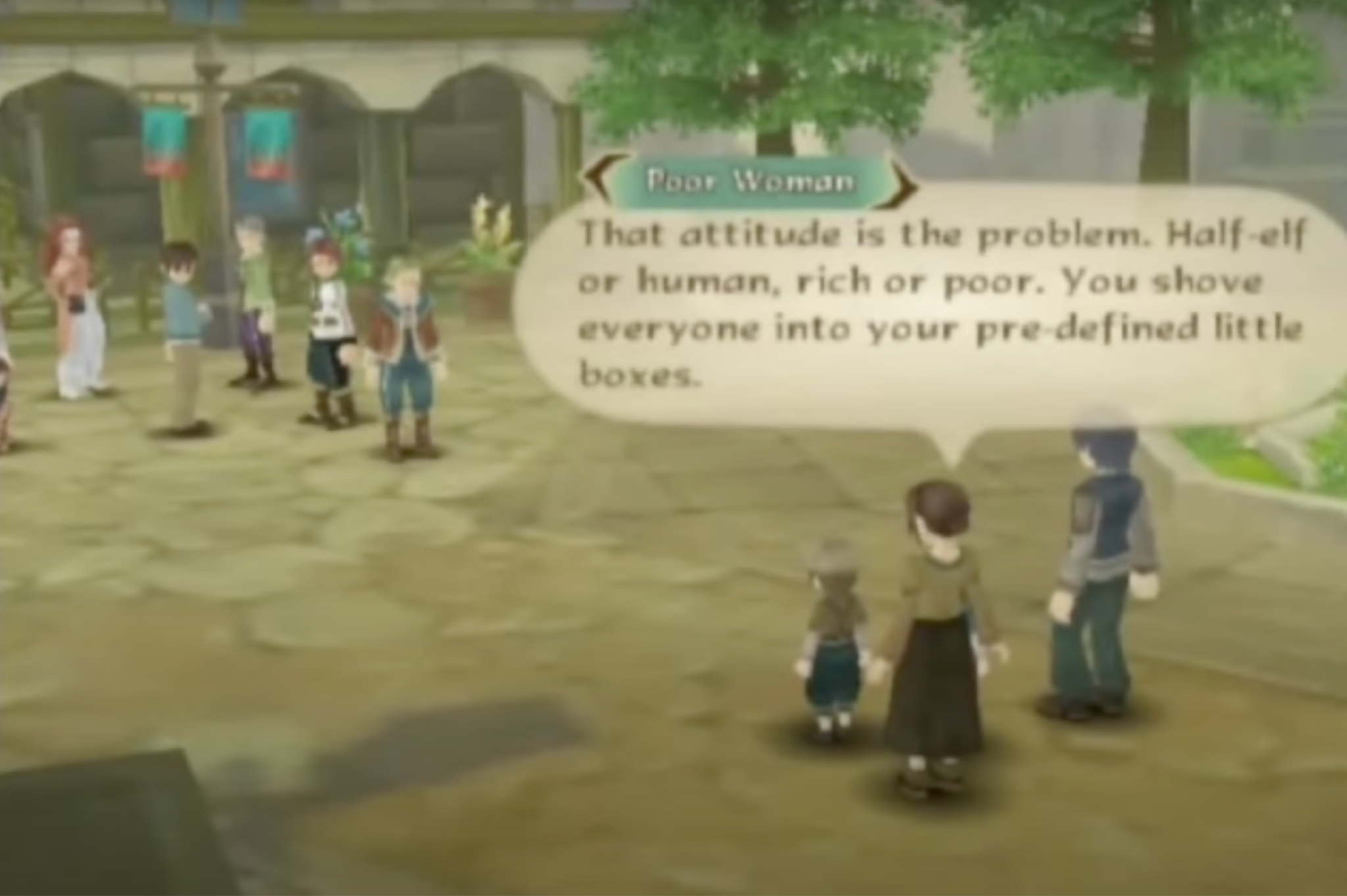

Poor Tethe’allans stand up to Tethe’allan nobles who are bullying a Sylvaranti and the party.

Emil earns his independent human life by consistently and rigorously making the context of everyone around him come alive, even though he doesn’t share it with them. In so doing, ironically, he fulfills the cosmic function of that Summon Spirit from which he’s individuated, Ratatosk. In Norse mythology, Ratatoskr is a squirrel who runs up and down the World Tree Yggdrasil to convey insults between the serpent that gnaws the tree’s roots (Níðhöggr) and the eagles that perch on its top branches.[6] That might initially seem like a somewhat morally bankrupt squirrel, but consider that the Norse cosmos is often understood to be born from disparity: from the interaction of the bright fire of Muspelheim and the dark ice of Niflheim came the primordial being Ymir, who occupied the void of the Ginnungagap, and the gods killed Ymir to fashion the heavens and earth from his body. The universe is fashioned and refashioned through violent acts of destruction and creation by different kinds of beings, from gods to animals to elves to dwarves. And, as Dawn of the New World shows us, much of the conflict can come from our senses of disparity festering, unspoken, rather than being voiced. It’s when the squirrel distributes hateful messages—when, for instance, Emil intervenes and exacerbates a conflict between entitled Tethe’allan nobles and a wayward Sylvaranti during another lengthy sidequest—that prejudices are laid bare and our preconceptions can be challenged, with poor Tethe’allans and peasants speaking up against the nobles. As Emil says, “maybe the problem is that we’re still looking at people in terms of Sylvarant and Tethe’alla”—a problem that can only be solved when people stop segregating themselves and start sharing their context with each other.

In the final, spiritual confrontation between Emil and Ratatosk, Ratatosk comes to understand and accept the praxis of Emil’s courage as an aspect of himself.

In a way similar to Luke in Tales of the Abyss, Emil’s journey is one of cosmic rectification: by becoming a medium in which individuals can benefit from each other’s context, he makes it possible for humans, half-elves, and elves to act harmoniously, charting their lives with mutual support—and this capacity for community makes it rational that the people of this world could survive and chart their own futures without the undue outside influence of demonic pacts and foreign mana animating their lives and wills, embracing the other—even “monsters,” whom Emil befriends throughout his adventure—as substantive and valuable. Emil earns individuals’ freedom in the cosmos by creating the conversational conditions to keep those with different heritages engaged with each other, proving to the withdrawn and distrustful Ratatosk that Mithos’ act of betraying him to restructure the world was an aberrant act of Mithos’ ideological solipsism, not proof of mankind’s fundamental corruption.

The Aselia games sit at an uncanny intersection of mythopoeia and scientific revolution. In a universe where the foreign species that made life possible on the planet is sequestered in a village bearing the name of Ymir, the dismembered and forgotten primordial progenitor of life, we encounter signpost after signpost of those who try to dominate the cosmos. The time-traveling Morrison clan evokes Philip Morrison, who contributed to the development of atomic warfare in the Manhattan Project only to later become an activist against nuclear proliferation, and who pioneered the gamma-ray astronomy that has helped us map our place in the universe. The Boltzman whose healing technique allows Raine to resurrect her fallen allies calls to mind Ludwig Boltzmann, whose work defining entropy for physical systems helped provide one path to solving the paradox of time’s arrow by showing how fundamental physics might have a “direction” in the same way we experience time. And Richter’s confrontation with a primordial keeper of the cosmic order rhymes with Burton Richter‘s discovery of a new subatomic particle through experimentation with a particle accelerator. Through all these portraits of investigating, mastering, and threatening the world with analyses that seek to transcend our individual perspective and explain all aspects of existence, the one constant that makes positive spiritual progress possible is the individual resolve to march forward and orient the ethical universe according to the direction of our action. The gift of Emil’s individuation is to make this action possible for everyone in the world.

The Ground of Action

When Marta finally comes to terms with the story of Colette’s life beyond her role in the destruction of Palmacosta and reflects on how myopically she’d viewed Colette previously, Tenebrae remarks that “We all play the starring role in our own stories. When those other than ourselves appear on stage, we tend to view them only as minor characters.” Chester teaches us that it may be conceptually impossible to turn those minor characters into main characters, and he also teaches us that those “minor characters” can color the entire fabric of the story by making sense of their lives beyond its reach in thematically meaningful ways.

On the way to Verius, Summon Spirit of Heart, Tenebrae reflects on the challenges of making sense of others in our life narratives.

For us players, there’s a surprising corollary about the order in which we ought to play these games. When chronologically related stories are published outside of chronological order, they always raise one pressing question for newcomers: “Should I experience them in the order they were originally published, or should I experience them chronologically?” Surely, there has to be a “correct choice” when we’re deciding whether to play these games in the order of release—Tales of Phantasia, Tales of Symphonia, Dawn of the New World—or in the order of historical events in their fictional world—Tales of Symphonia, Dawn of the New World, Tales of Phantasia. But the disciplined directionality of Chester suggests that this is the wrong way to think about these games. In a collection of games where we learn many more details about overall world history than we do in most other Tales games, our interpretation tells us that there is no single way to arrange all the etiological information about a story’s events in order to get a single, comprehensive understanding of that story; such an understanding is the same kind of fantasy as Mithos’ ideal world for himself and his sister. Nor can we blindly play these games without regard to order and interpret their stories as unrelated events; that would do violence to the interconnected structure of these fictions in the same way that Dhaos’ atemporal schemes do violence to Aselia. What the symbolism of Chester prescribes is a middle path: mindfully journeying through these games in whatever order we choose, recognizing that we will never fully identify with the total context of these fictional worlds, but being conscious of why and how we’re choosing to play them, along with what our experiences in the games are revealing to us about those choices. In this light, it’s equally permissible to (1) discover Tales of Symphonia as a kid, fall in love with Lloyd’s commitment to justice in the face of discrimination, and follow this experience with Dawn of the New World and Tales of Phantasia as a way of tracing and making sense of the legacy of Lloyd’s ethos (as I did as a kid), or (2) discover the negative space of Chester in one’s own attention to the story of Tales of Phantasia, and trace that attention through Tales of Symphonia and Dawn of the New World to see how that negative space colors the series’ theming more broadly (as I’ve done in this study). My friend and colleague Dan Hughes went so far as to play part of Dawn of the New World before playing Tales of Symphonia and told me that, far from muddying his ability to make sense of the story, this drew his focus to critically and skeptically evaluating Lloyd’s actions and beliefs throughout Tales of Symphonia, unsure, in light of the Blood Purge that begins Dawn of the New World, whether Lloyd was really trustworthy.

This points to a broader insight about what it is to play Tales as a series, as well as why I’ve been criss-crossing throughout the series in my Tales of Praxis studies rather than studying the games in the order of their release. Most of these games aren’t related by representing a single fictional world like the three we’ve just studied, yet they are all related when we choose to chart our own path through them, focus on particular themes we find them reflecting in our journey, and see how every further game in our journey further sculpts our understanding of those themes. As members of a series, the Tales games offer a common skeleton of concerns about the nature of identity, action, and the method through which individuals create the future through community; by attending to the friction between our own gaming experiences and that skeleton, we can uncover a meaning in the series that uniquely derives from our specific journey and interests, rather than some encyclopedic understanding unifying all the lore and trivia. And Chester suggests that the latter sort of understanding, attractive though it may be, is an illusion: the only kind of understanding we would want to give ourselves and others is the experientially grounded one that informs how a specific gamer can make sense of her lived experiences within the game, not one treating the games as abstract and static objects.

In my comparative study of Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia: Definitive Edition, I argued that the symbolism of the Swordians and Dein Nomos teaches us how to become free as individuals by respecting and supporting those in the past and present who live in contexts different than our own. The symbolism of Chester stands one step further back in the Tales series’ philosophy of identity and action, grounding our capacity to act in the first place.[7] Especially in the heroic sagas of JRPGs, it’s tempting to imagine protagonists like Stahn, Yuri, Cress, and Lloyd as idealized agents. We may not know how their actions will impact their relationships and communities, but we see it as a foregone conclusion that they will act: it’s in their nature as the main characters of their stories that their identities are sufficiently well-defined, their motives sufficiently strong, and their traits sufficiently vivid that they will have the reason and agency to conceive of and take an action in any given scenario. More deeply human than such a facade, Chester Burklight shows us all the messiness that coagulates in the gap between what it takes to live and what it takes to act. So often, we find our sense of self nested within traumas, goals, communities, and history that simultaneously define the context we would require to be fully at peace with who we are and deny us access to that context: we see the need to process our sister’s murder yet have no means to do so; we feel the need for justice in the world but don’t know enough about the world to understand what that looks like; we see the value in others’ lives yet cannot infer that value in ourselves. Chester’s arrow teaches that the first step in taking action—the one that might seem so obvious that we’re rarely even aware of it—requires a mystical leap of faith. If we are to achieve any sort of harmony between ourselves and the world beyond, we must recognize the necessary deficiencies in our understanding of precisely how we’re connected to the myriad causes and effects across the cosmos, and we must turn ourselves into an effect all the same. We must create our identity as agents by committing to action, allowing the world to orient itself around the principles our bow and arrows bring to life.

Chester Burklight, as represented in Tales of the Rays.

- I collected and calculated these figures from the game script transcribed and published by Unos Hambalos on GameFAQs. My thanks to him for creating and sharing an invaluable resource for the close reading of a video game. ↑

- Note that Tales of Phantasia also received the sequels Tales of Phantasia: Narikiri Dungeon and Tales of the World: Summoner’s Lineage, which actually marks the Aselia games as a quintet rather than a trilogy. Since we haven’t received an official localization of these sequels in the West, I’m limiting this analysis to the other three Aselia games, treated somewhat artificially as a trilogy. As we’ll see, though, my analysis implies that there isn’t a “correct” sequence to play these games, which we might read as further theoretical validation that there isn’t anything essentially “trilogy-like” about their storytelling at all. With that in mind, it would be interesting to extend the interpretation presented here to Narikiri Dungeon and Summoner’s Lineage and see whether the thematic and structural conclusions hold equally well. ↑

- In the West’s Game Boy Advance localization, Derris-Kharlan is anglicized as “Derris Karran” (like the Aselian calendar is called the “Aserian calendar”). I’ve chosen to update the stylization to render it consistent with the naming convention in Tales of Symphonia and Tales of Symphonia: Dawn of the New World. ↑

- In conversation on the Tales of Praxis stream, Grailzy5 suggested “racism” as a unifying theme. As we’ve already seen in Tales of Phantasia, there’s plenty of racism in the relations between humans, elves, and half-elves, and other forms of discrimination take center stage in the games as well (e.g., between Tethe’allans and Sylvaranti following the reunification of the worlds). These concepts certainly need to be part of the story of how we make sense of these games, but, to my mind, they leave some of the games’ core, organizing conflicts relatively untouched. How can we explain Dhaos’ atemporal desire to bring energy back to his dying homeland in terms of discrimination? How does the struggle between human conscience and primordial will in Emil and Ratatosk reduce to matters of discrimination? My hope is that my suggested model of time’s arrow can make sense of these broader conflicts while also illuminating why discrimination naturally resonates with those conflicts. ↑

- This is an oversimplification for the sake of clarity. More precisely, having Emil pledge loyalty to Lloyd, enter the Triet Ruins, and get hit by lightning in the Temple of Lightning all increase an invisible quantity tracked throughout the game (the pledge by 5 points; the other events by 1 point each). If this quantity reaches or exceeds 10 in a playthrough, then the player will only be able to access the self-annihilation and integration endings, not the individuation ending. Thanks to GameFAQs user Kirby647 for this exceptional Dawn of the New World sidequest guide, which details this mechanic and the structure of other optional paths through the game. ↑

- I’m by no means a scholar of Norse mythology and haven’t made an adequate study of the literature here to offer an entire “Norse reading” of the Aselia games in the way I previously offered a Lurianic Kabbalistic reading of Tales of the Abyss. My hope here, rather, is merely to show how a superficial familiarity with this mythology provides another textually motivated, thematically resonant and reinforcing dimension to the interpretation I’ve already derived from these games through the rest of this study. ↑

- That Chester’s symbolism is only a first step, insufficient as a full philosophy of action, is most apparent to me in the fact that all of these Aselia games lack a key moment I discuss in both Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia (and which also features in Tales of the Abyss): neither Mithos and his party, nor Lloyd and his party, nor Ratatosk and his party, nor Cress and his party get consent from the rest of the world for the ways in which they elect to change the nature of the universe (splitting the world, bringing it back together, weaning it off of mana, making a Mana Seed and sending it to Derris-Kharlan). The conceptual distance between what it takes to catalyze one’s own activity and what it takes to square that activity with others, to my mind, captures the deepest thematic divide between my Destiny/Vesperia duology and the Aselia games. ↑

2 Comments