The following is an entry in Tales of Praxis, a weekly series studying the storytelling and philosophy of Bandai Namco’s Tales series through written analyses and streamed playthroughs of a wide range of the Tales games on With a Terrible Fate’s Twitch channel and YouTube channel.

Elementally-separated aer transitions into matter in stages, and eventually becomes stable. I’m going to stop its transition between the two states and develop a converter formula.

[…] It’s a state that’s closer to matter than to aer, but it’s still not quite matter. We call it “mana.”

—Rita Mordio, Tales of Vesperia

I want to say one final word to you. I lied to you. You were not chosen. In the beginning, people were blessed with the power to truly understand one another. However, this power was lost by the time of the Aeth’er Wars. But you found that quality within yourself even before you met me. It was very unusual to find someone like you, but your abilities are not extraordinary. This is because this power, this ability, lies dormant within everyone.

[…] I think I can leave the world in your care. We’ll protect the world for the present. But you must decide the future of the world by yourselves.

—Dymlos, Tales of Destiny

Tales of Vesperia teaches us how to forge a sword, and Tales of Destiny teaches us how to return a sword to its forge.[1] Together, they show us what it means to act freely and shape the world as individuals through our communal relationships, rather than being subsumed or estranged by them.

(Spoilers for Tales of Destiny (PlayStation, 1998) and Tales of Vesperia: Definitive Edition (PlayStation 4, 2019).)

In isolation, these JRPGs tell stories of heroes embedded in a world whose broader dynamics threaten to nullify any autonomous value in their individual actions: Tales of Destiny presents a party enacting a destined course of events that history demands be reenacted; Tales of Vesperia illustrates an irreducibly diverse group of characters whose choices and journeys constitute 9 more threads in a universe ruled by chaos rather than a singular, coherent narrative. Once we place these games in conversation with one another, however, those very same narrative elements that threaten to disenfranchise our heroes’ autonomy present themselves as two sides of a dialectic analyzing what it takes to distinguish one’s autonomy from the influences of history and entropy, the past and present forces which relocate our decision-making outside of ourselves. Experienced jointly, the quests of Stahn, Yuri, their friends, and our paths as players define a praxis of radical individualism: the principle of will that allows people to determine not only their own actions, but also the future course of events in their world, without undue interference from factors beyond themselves.

Judith opines on the relationship between weapon and user as Yuri inherits Claiomh Solais from the lower quarter.

I want to convince you that these two Tales games thread the needle of individual agency between the two existential poles that threaten to render our personal choices inert: the threat of the world’s past entirely determining its future, and the threat of world events being too purely stochastic to respond to any principled, guidance influence from an actor within that world. By analyzing the personal growth of each game’s party in parallel, we unlock a model for how individuals can change the world by (1) releasing the grip of history on the present and (2) supporting others in their personal journey to decide what they care about independently of any historical context. In so doing, we discover not only a principle of action we can apply in our lives beyond these games, but also a lens through which to understand and share the unique value of our playthroughs without erasing the narrative value common to all playthroughs of video games.

This study is forged in 3 parts:

- I first motivate and analyze “the symbology of the swords,” the nature and thematic content of the Swordians and Dein Nomos in Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia. I argue that the Swordians represent a method of agency that allows the wielder to be motivated by the past without reducing herself to the past, whereas Dein Nomos represents a method of coordinating collective action by empowering the personal narratives of diverse individuals on their own terms.

- I then trace the development of the swords’ symbology across the plots and conflicts of each game, each broken down into 3 “acts” according to the antagonists around which each successive conflict is organized. I argue that both Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia illustrate characters that develop their own principles of action—and, ultimately, the ability to shape their world’s future. In both games, this is achieved through a progression from (1) overcoming personal inertia by undertaking an instrumental quest through which one uncovers one’s desires, to (2) experiencing betrayal as a means of clarifying how one’s desires relates to those of other agents, to (3) empowering and situating the stories of everyone other than oneself within their proper contexts.

- I finally step outside of the games’ plot and argue that their structure and avenues for player choice empower us, the real players of Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia, to learn and enact the games’ praxis as we play them, using their optional characters and optional storylines to define our own relationship with the overall narrative according to our specific playthroughs, without thereby invalidating the principles of action motivating specific characters or other players.

When all is said and done, we arrive at a perspective on the Tales armory that rejects all flavors of fatalism in favor of clear, practical methods for reshaping the world by witnessing and catalyzing the mosaic of every willful agent who inhabits it.

(Note: this study specifically treats the English releases of Tales of Destiny for the PlayStation (1998) and Tales of Vesperia: Definitive Edition for the PlayStation 4 (2019).[2])

Swordians and Dein Nomos as Principles of Volition in Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia

To wield a sword is to take up an instrument forged by a community, for the sake of your individual maxims.

Swordian Dymlos (left) and Dein Nomos (right), official artwork.

While magical, plot-centric swords are common across stories and Tales games alike,[3] the Swordians and Dein Nomos have an intimate connection: they are both artifacts of the energies that have animated their worlds, and they are the tools with the power to liberate their worlds from dependence on that energy. In the hands of the enlightened wielder, they replace the animus whence they came with a more personal and transparent motive force: human will. By analyzing the ontology of each type of sword—what it is, what it does, and how it came to be—we can interpret them as symbols for particular systems of agency within each story, enabling their wielders to achieve particular ends in the same way that a sword literally functions as a tool for advancing and defending one’s agenda. When we then turn to the plot of each story, we’ll see that these symbols can function as ciphers for interpreting how our heroes empower themselves, each other, and the world to determine their own future based on nothing other than clear-minded, individual volition.

Swordians Bridging Past and Present in Tales of Destiny

The Aethersphere reasserting itself over the planet as Hugo’s plan comes to fruition in Tales of Destiny.

The world of Tales of Destiny is one in which the course of society, economics, and world events are shaped by a foreign energy: Lens, derived from the comet that hit the planet over 1000 years before the events of the game—making magitechnology possible, but also devastating the planet’s ecosystem, seeding the disparity that would color the future trajectory of the world onward from the point at which those who left to live in an elevated Aethersphere, the Aetherians, enslaved those Er’thers left behind on the surface. The Lens fuel everything from monsters, to monster barriers, to weapons of mass destruction like Belcrant—to the Swordians, sentient swords developed by repentant Aetherians who defected back to the planet in an effort to overthrow the fascist regime of Kronos’ Aethersphere.

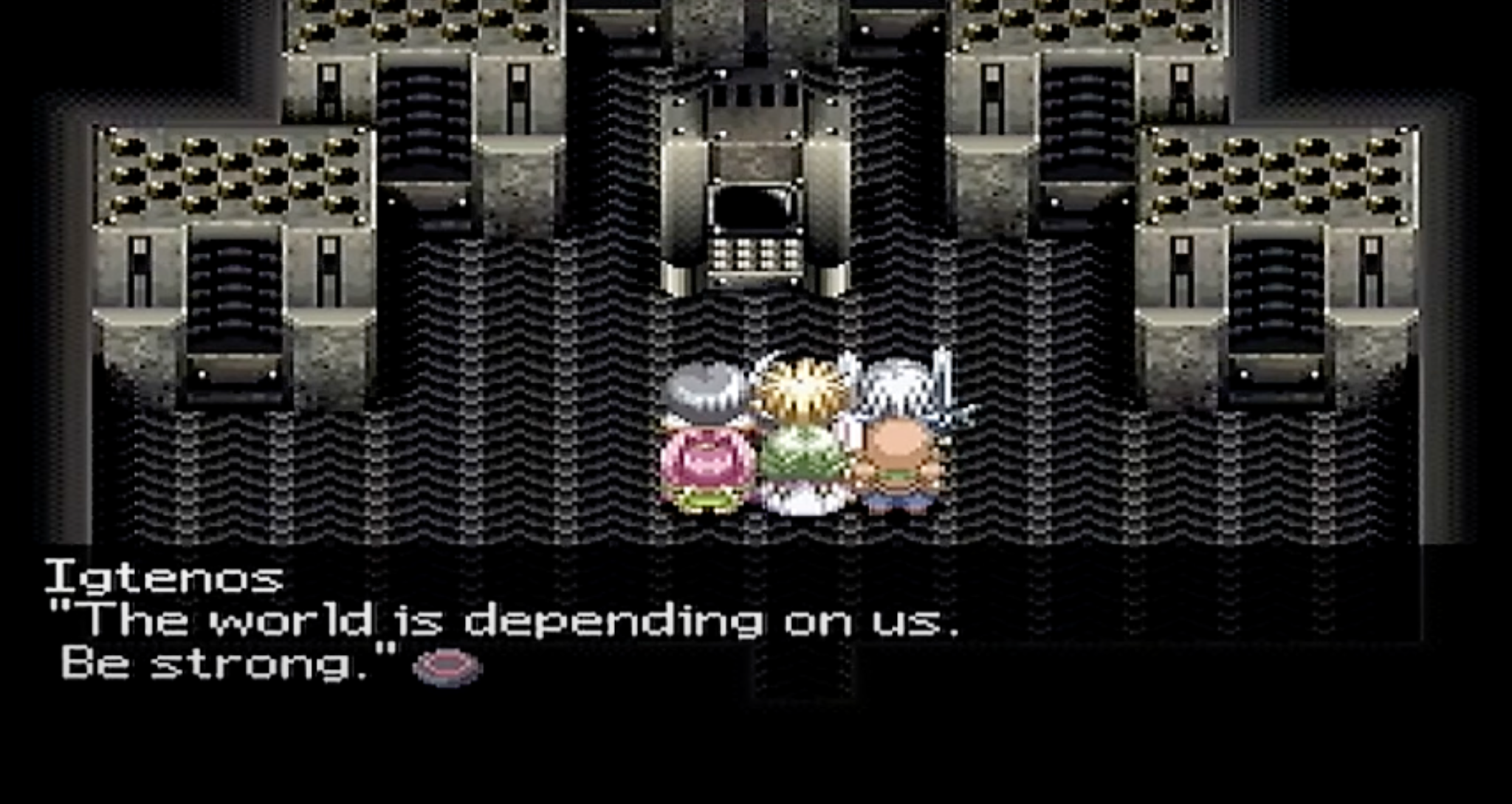

Igtenos reflects with fellow Swordians Dymlos, Atwight, and Clemente as they prepare to resolve their history from the Aeth’er Wars.

The Swordians, like the Lens from which they are derived, reach backward to a foreign world in order to serve as tools in their present-tense context. Their Core Crystals store imprints of human personalities, turning heroes from the 1000-year-old Aeth’er Wars into tools to empower those who can hear their voices and use their abilities in the present. In only the second entry in the Tales series, Namco created a format for bringing 8 party members into battle at once: 4 humans, Swordian masters, equipped 4 with Swordians—weapons, but weapons with a point of view, the ability to use equipment (Aura Discs), and gaining experience to unlock new spells and parameter increases. These living swords await those who are apt to relate to them, and they empower those “masters” to pursue and succeed in their own missions—all despite the fact that these swords were forged and defined by a mission from an entirely different era than the masters.

Symbolically, these Swordians represent conflicts from the past empowering new principles of action in the present. The obstacle to overcome in successfully availing oneself of this tool, we’ll see, is in understanding how to relate one’s activity to the past without collapsing into the history that preceded one.

Dein Nomos Bridging Individuals with Community

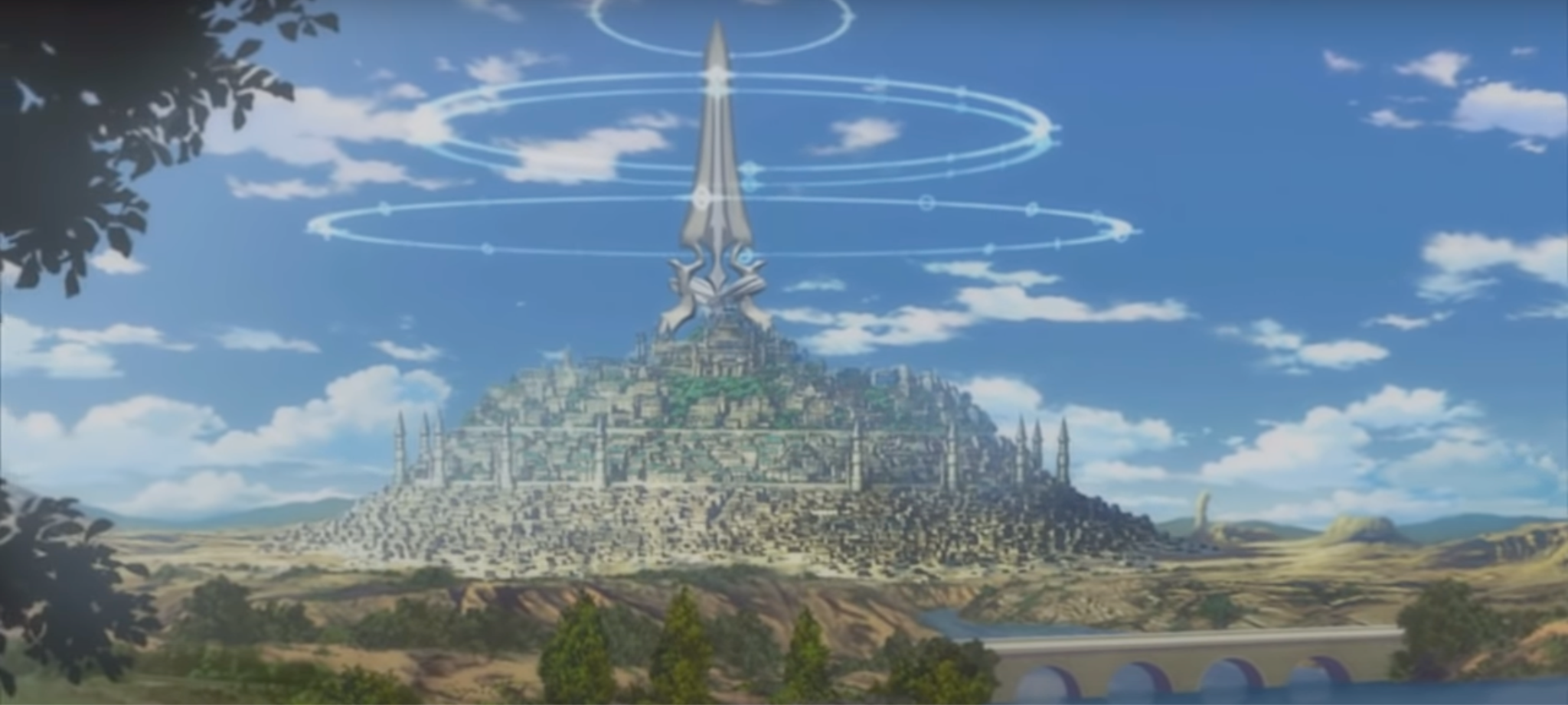

The Imperial Capital of Zaphias shielded by its barrier blastia, as seen during our introduction to Terca Lumireis at the start of Tales of Vesperia.

Tales of Vesperia introduces us to Terca Lumireis, a world animated by chaos. Humans have protected themselves from monsters, waged war against each other, and advanced society by manipulating aer, a substance defined more so by its functions and consequences than by its origin or essential attributes. Aer is introduced to us as a source of “primeval power” which emanates from Terca Lumireis through the natural springs of aer krene, and we eventually come to know it as “the lifeblood of this world”: the “sublimation, reduction, formation, and dispersion” of aer’s distinct and diffuse elemental forces undergirds all of existence and the very possibility of the material world.

Humans manipulate aer by interjecting themselves and their desires into Terca Lumireis’ natural ecosystem, repurposing apatheia—the ensouled masses of aer coagulated within Entelexeia, the species that monitors and regulates fluctuations in the flow from aer krene—to craft blastia, gems that yield certain effects by expending aer according to specific, engraved formulae. The rise of a blastia-dependent human civilization disrupts the natural balance of aer in the world, causing aer krene to overproduce aer to the point of toxicity, metamorphosing the Entelexeia into constituents of the Adephagos, a world-enveloping cataclysm that consumes the technology and society that begets the surplus.

The Adephagos, as witnessed in Duke and the party’s final confrontation with it at the climax of Tales of Vesperia.

Already, it’s evident that the nature of Tales of Vesperia’s world is more complex than that of Tales of Destiny‘s, and that difference is crucial in their representation of different kinds of inertia which the protagonists must overcome in order to claim their individual volition. Where Tales of Destiny’s players and characters are primarily kept in the dark as to the question of who stands in what relationship to which segments of the world’s relatively simple history, Tales of Vesperia’s players and characters are constantly trying to locate themselves within chaos. The history of Terca Lumireis is itself one of humans struggling to find a foothold from which to establish a sense of stability in a world with primeval, undirected elemental energy, and monsters with which rational communication is impossible. In the midst of such entropic origins, even our ability to access and understand history is limited: the Great War that transpired only a decade before the events of the story is a veiled conflict that doesn’t receive a full explanation by the end of the game;[4] where Tales of Destiny features a literal Tower of Knowledge and journeys to meet the characters and explore the central set-pieces of the world’s history, Tales of Vesperia leaves us and its heroes to uncover anecdotes about world history and ecology from second-hand sources like fairy tales, esoteric murals, and Entelexeia, distrustful guardians of the world order who act as much by evolutionary instinct as by rational deliberation.

Duke expresses the praxis of Dein Nomos as he sees it, as he and the party approach Alexei and a kidnapped Estelle in the Shrine of Baction.

Individuals make sense of this chaos through the same approach embodied by the nageeg, the Krityan exegetical practice of using an incantation to unlock stories contained within objects. When the party needs to know how to guide their actions to help Estelle and cope with excess aer, Judith is able to draw a practical meaning out of the lore contained in Myorzo’s mural with the nageeg. Dein Nomos is an embodiment of this principle: it cuts through the chaos of the world by coordinating various, otherwise chaotic elements of the world in accordance with a single principle of action. Most literally, the bonafide Dein Nomos mitigates chaos by quieting overtaxed fonts of aer, and serves as the “key” to the tack humanity took in escaping their pure dissolution into entropy after the first appearance of the Adephagos in ages past: the key to Zaude, the enormous defensive blastia that suppressed the Adephagos, and proof of the lineage of surviving Children of the Full Moon, those people with the ability to directly manipulate aer who fueled Zaude and begot the bloodline that would birth the Imperial Royal Family thereafter.

But the irony of Dein Nomos is that at the very same time as it is a unique sword with a central role in human history, the universe of Tales of Vesperia is riddled with individuals working to create and/or wield their own “Dein Nomos”: either an overt copy of the royal sword, a functionally equivalent sword, or a different unique sword with similar symbolism (e.g., Claiomh Solais, Rag Querion). In all of these cases, from Alexei’s False Dein Nomos to Brave Vesperia’s Vesperia No. 2, the wielder seeks to enact a certain activity, a certain worldview, through the support of a wide range of other individuals—though whether those individuals are willing or unwilling, present or past, are factors that vary widely, illuminating the path by which one can arrive at radical individualism by interrogating the missteps one can take along the way.

Symbolically, Dein Nomos, in all its forms, represents the collective will of a community to enact a specific principle of will in the world—to legislate oneself according to a collectively defined law, or ‘nomos’ in Greek. This sword is forged by many individuals with their own reasons for supporting its use, yet it is the kind of thing that can only be wielded by one person at a time—the instrument of one person who motivates and inherits the intentions of many, without erasing the unique desires of community members in service of the collective.

Left: Stahn and the other Swordian masters let their Swordians go for the sake of annihilating the Eye of Atamoni. Right: Brave Vesperia and its affiliates pool their individual life energy to collectively fuel Brave Vesperia No. 2 and transform the Adephagos.

On this reading of the swords, it’s no coincidence that human lifeforce is just as capable as providing and channeling energy as aer; it’s no coincidence that the Swordians’ journey ends with the collective sacrifice of their lives in exchange for the Eye of Atamoni’s destruction. The joint lesson of Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia is that the free, intentional expression of one’s own life requires understanding and supporting the lives and intentionality of others: self-determination is possible, but not in a vacuum.

Learning How to Wield the Sword: Progressing from Inertia to Radical Individualism through the Plots of Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia

Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia are a remarkable duology because they show how to logically progress from a total sense of personal disorientation to a justified, beneficent ethos which one can consistently impose on the world beyond oneself. The journey to radical individualism from a complete lack of self-determinism is one that must occur piecemeal.

For the arrival at this kind of personal autonomy to be meaningful, the agent must begin his journey from a position of fatalism: the complete lack of confidence in one’s choices to influence the course of one’s life and the world’s trajectory. The value of reading Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia in conversation with each other comes from their antithetical yet complementary approaches to this journey. Both jostle their heroes out of inertia, but Tales of Destiny situates its heroes in an idle inertia, whereas Tales of Vesperia presents its heroes in a directionless course of action with no reason to correct their trajectory.

A world of new possibilities bursts forth from its confines within the oppressive, historical influence of the Aethersphere at the end of Tales of Destiny.

The parallelism of the remedy in these cases shows that a single kind of willpower can cure us of the full manifold of existential paralysis we might encounter in our lives: through a measured progression from (1) instrumental activity to (2) betrayal to (3) intrinsic recognition and support of others, we can define and enact our will as something that makes a metaphysical difference to world history, actuating itself in the conceptual space between the two poles of (A) a fully deterministic, “destined” model of events, and (B) a completely chaotic and random evolution of actions which could not be coordinated for any collective purpose.

To reach and understand the content of this praxis, we’ll consider the three “acts” of each game in parallel: the struggle between the heroes and the first villain, the confrontation between the heroes and the puppetmaster of the first villain, and the finale between the heroes and the final obstacle to their fully actualized individualism.

Act 1: Overcoming Inertia through Instrumentalism

How do you discover your agency, your reasons for action, in a world that factors you out of your own life’s trajectory?

Rita prompts Estelle to self-consciously consider her future course on the party’s way from Halure to Capua Nor in Tales of Vesperia.

Before you can take up a sword, you need clarity on your reason for doing so. Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia illustrate that this initial call to action looks remarkably similar whether one finds oneself subordinate to the past or lost in the noise of the present. In either case, awakening the protagonists’ internal motives requires connecting their conception of their own actions with a finite model for the motivation and impact of those actions on the world. By presenting the heroes to themselves and each other as instruments, the story invites them to evaluate their genuine motivations and how they want their lives to impact the world beyond themselves.

Tales of Destiny: Contextual Dishonesty

The most efficient way of connecting past context with present action is convincing current heroes that their actions are destined.

Dymlos motivates Stahn into getting both of them off of the Draconis and onto their mutual story by deceiving him, claiming that Stahn and he were destined to meet and unite.

Tales of Destiny opens on a set of human heroes who all need to be called to action to overcome the inertia of their idle states:

- Stahn, through whom the plot is focalized, identifies his goal in leaving his small-town country origin to be “see[ing] the world and maybe becom[ing] rich and famous along the way.”

- Garr is in a kind of self-imposed exile from his princely duties in Phandaria, instead studying archery in the mountains under Alba.

- Rutee is seeking Lens, treasure, and money in an ad hoc way with an amnesiac, trying to save the Cresta orphanage, in which she was raised, from demolition, with no clear plan for doing so—more of a “money-obsessed maniac,” in Atwight’s words, than a proper savior.

- Philia is literally petrified and figuratively paralyzed, her faith upended by a schism with her spiritual leaders, Lydon and Batista, along with the weaponization of a religious object, the Eye of Atamoni.

Those with no clearly defined principle of action guiding their lives are apt to be manipulated by others who instill them with a “purpose” in the form of a quest with ulterior motives, and Tales of Destiny’s first act is saturated with this kind of manipulation from both heroes and villains. High Priest Lydon Bernhardt, in his efforts to seize the Eye of Atamoni’s power and dominate the kingdoms of the world with a monster army, uses religious followers like Batista and political aspirants like King Tiberius as pawns to conquer territory and effect his relocation with the Eye of Atamoni to Phandaria. The heroes’ journey itself begins as something between a hostage situation and a fetch quest, led by Leon (another character with ulterior motives) by order of the Kingdom of Seinegald, under threat of electric-shock tiaras and the promise of financial reward, to retrieve the Eye of Atamoni from Lydon.

Following his defeat at the hands of the party, Tiberius rues that his ambitions turned him into one of Lydon’s tools.

Most saliently for our purposes, three swords call out to their new masters and empower them to act, all the while hiding their true mission to destroy the Eye of Atamoni. The Swordians Dymlos, Atwight, and Clemente motivate Stahn, Rutee, and Philia to inadvertently advance the Swordians’ agenda by articulating the special roles that these human masters have to play in the world, absent any particular objectives the weapons might have: Clemente tells Philia that he has awoken “a hidden skill within [her]” and that she will conquer “many trials” which lie ahead of her; even Atwight, saddled with the more reserved Rutee who refuses to open her mind to her Swordian, motivates Rutee through her (Atwight’s) instrumental utility to her, casually mentioning that Rutee would be “a defenseless girl” if she didn’t have a Swordian, as well as motivating a collaboration between her master and Dymlos’ by saying that “[i]t would feel safer if Dymlos was with us.”

The Swordians—these unresolved conflicts of the past, lacking the autonomy to see their missions through on their own—are left to tell a kind of half-truth to their masters, inspiring them to overcome their inertia without illuminating the stake they have in their masters’ activity. This is an intuitive place for the masters’ self-actualization to begin: before they can relate their experiences to those of anyone else, they need to clarify their own desires and intentions in the present-tense of their lives. Conceiving of their relationships with the actions of history is a vacuous exercise without a point of reference in their present-day identities. Thus:

- Philia draws strength from Clemente’s paradigm of her hidden skill and promised trials to evolve from (1) a position of inert submission to Atamoni to (2) a personal relationship with Atamoni based on belief in the innate kindness of the world, asserting her newly articulated values in the face of priests and her own mentor, Batista.

- Rutee recognizes that the utility of others, like Atwight to her, is valuable for others’ own purposes and not necessarily something to be co-opted by her, leading her to counsel Mary, her first companion, to stay behind and “treat the wound in Dalis’ soul” after Mary and Dalis, Mary’s husband, recover their memories, as that is “something [Mary] can do that other people can’t”; subsequently, we witness Rutee finally finding the presence of self to confess to Stahn why she’d been seeking money all along.

- Stahn, acknowledged by Dymlos as someone who “seem[s] like a good person” for all his naivete, extends that same recognition and encouragement to virtually everyone else he encounters, quickly reconfiguring his journey from something that inertly gestures at ambition (“and maybe become rich and famous along the way”[5]) to something that finds its purpose in those with whom Stahn surrounds himself: he acknowledges and vocalizes the kindness in Rutee when she stands up for bullied orphans in Neuestadt without a utilitarian agenda, well before she’s ready to admit her origins and motives; when Philia is ready to collapse into her own naivete for having trusted Batista, Stahn recognizes that she’s not naive, but rather kind, paving the way for her personal understanding of Atamoni; he welcomes Karyl into the party in Aquaveil without a second thought despite Karyl’s personal motivation to save his best friend rather than prioritizing the defeat of Lydon, telling his comrades that “it’s better to have more people on our side” and it should “count for something” that he facilitated their escape from guards upon their arrival in Aquaveil; he even asserts his friendship to Leon at the last, upon their return to Seinegald after defeating Lydon, in the face of Leon’s physical nausea from air travel and psychic nausea at being forced, for reasons yet unclear, to callously deceive and manipulate everyone around him.

Philia asserts her new understanding of Atamoni as universal kindness to her former religious mentor, now puppet of Lydon, Batista.

We identified the Swordians as symbolizing conflicts from the past empowering new principles of action in the present. At this first stage in the development of these principles of action, these tools turn sheltered individuals into sword-wielders by providing them with a framework to orient themselves in their present world, remaining deceptively silent about the historical influence impressing its gravity upon that world and its people. In this first act, the Swordians are remarkably similar to another sword: the nameless blade borne by an amnesiac Mary, acting as a tool for her to help the party in their current mission against Lydon while binding her to a past which she cannot access alone.

Mary shows Stahn her sword, her one link to an unknowable past.

The antagonist of each act in Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia shows us the limitations of the party’s current agency and what they must overcome in order to reach the next stage of defining and enacting their volition. Tales of Destiny begins this dialectic with the portrait of Lydon: he wields a critically damaged version of the Swordian Igtenos, with no sentience that could begin to articulate the relationship between Lydon’s present plot and the history within which Igtenos was forged. In the absence of a robust understanding of the relationship between one’s actions and the actors of the past, one’s goals in life assume a kind of toxic timelessness: like a corrupted priest obsessed with an esoteric religious artifact, the agent’s perspective on her actions transcends any particular historical context, leaving her vulnerable to being consumed by the historical relevance she fails to see in her own tools—as Lydon is when he is unceremoniously swallowed up by the Eye of Atamoni, that historical relic which he took to be proof of his divine right to supreme power (a denouement that occurs, fittingly, in the middle of an enormous clock face, the irony of which Lydon could never grasp).

Lydon is overtaken by the power of the Eye of Atamoni, a historical tool he does not understand, at Heidelberg Castle before the party’s eyes.

It’s no wonder, then, that this first step in the heroes’ journey, which must begin with their finding a sense of self in an ahistorical present, is also rife with those who take advantage of that ahistoricism for reasons more malicious than the Swordians. Hugo Gilchrist’s vision for the world’s future shapes the Oberon Corporation into a global institution using Lens, objects of the past, to manipulate the course of international events; Leon’s attachment to his own past shapes him into a broken traitor in the party’s midst; in the background, Kronos looms over them all, even the Swordians, invoking the past most unambiguously through means entirely opaque to our temporally muddled party. The Swordians had to begin their relationships with their masters from a position of contextual dishonesty, but it’s also this lack of honest communication that makes possible Leon’s final con, putting the Swordians into stasis with clandestine Aura Discs and lying that they fell silent because their innate purpose had been fulfilled.

To shape the future through their individual principles of will, Stahn and his friends must learn how to become more honest about the different contexts in which their wills and their tools are embedded.

Tales of Vesperia: Chaotic Self-Discovery

When your world is too chaotic to locate yourself within it, sometimes the best you can do is to choose a “flow” in the streams of chaos within which to cast your lot.

In Capua Torim, Flynn bemoans Yuri’s inertia in the time since he rejected the path of a Knight without undertaking an alternative positive course of action.

Where Tales of Destiny opened on characters that were inert in the sense of not moving in any clearly defined direction, Tales of Vesperia opens on a cast that is inert in the sense of carrying on with a course of action which they didn’t positively choose to undertake based on their desires. Each member of the party is guiding their actions based on what they don’t want to do in the world rather than something they want to do:

- Yuri has rejected the path of the Imperial Knights, living in Zaphias’ lower quarter in the absence of the direction the Knights provide their members.

- According to Yuri, Repede “doesn’t think of himself as a dog,” which is “why he uses weapons and items.”

- Karol is constantly running away from, or rejected by, the guilds that take him in, seeking a home only to find places and worldviews in which he does not fit.

- Estelle jumps at the prospect of a journey that will justify leaving her seclusion in the castle.

- Rita withdraws herself from the uncertainty and potential for abandonment and betrayal that come with human relationships.

- Judith is “cleaning up the mess” of her father’s Hermes blastia “before anyone [can notice],” erasing the legacy of her family.

This might seem like a more decisive set of activities than Stahn and his friends’ at the beginning of Tales of Destiny, but it doesn’t go any further distance toward defining these characters’ individual principles of will: to define oneself solely through the rejection of one principle of action, particularly in a world with a diverse range of obscurely interrelated factions and possible modes of engagement, is to lose oneself in the deluge of all other possibilities, with no promise of a coherent path that will yield personal insight or impact. But this kind of inertia does provide a different developmental path than Stahn and the Swordians have available to them: rather than being manipulated by others into acting from unclear contexts, they can send themselves on instrumental quests with no clear promise of a broader mission or intrinsic fulfillment, and set themselves up to clarify their personal motivations and desires through the pursuit of that quest’s finite objective.

At the end of Tales of Vesperia‘s first act, Estelle reaffirms her desire to continue on the loosely defined party’s even more loosely defined adventure.

The heroes of Tales of Vesperia begin their journey simply by finding some quest to begin based on what’s right in front of them, without some further agenda or high-minded mission: Yuri takes it upon himself to find the thief of the lower quarter’s aque blastia; Estelle sets off to warn Flynn of those conspiring against him and the Imperial Knights. Along the way, other party members attach themselves to the party not because of some shared vision of a future they wish to create together, but rather for their own instrumental reasons: Rita wants to investigate blastia and investigate Estelle as a clue to the Rizomata Formula; Karol looks to Yuri and Estelle as a means of helping him to prove himself to Nan, and to give him a new sense of group identity in place of his latest failed guild membership; Judith partners with Yuri when his mission to retrieve the aque blastia intersects with her journey to destroy Hermes blastia.

As the characters set off on their first tasks together, they repeatedly emphasize the priority and primitivity of their desires in grounding their actions: Rita can’t articulate her attachment to blastia beyond her sense that “they’re fun”; Yuri acknowledges that, for many of his interests, “the reason I like them is because… I like them”; Judith is “destroying [Hermes blastia] because I want to.” This is a group of people that explains their courses of action to each other purely through their immediate desires, which is enough to get them in conversation with one another—but it’s also why we see them, remarkably often, getting together to reevaluate whether and why they will continue traveling with each other to the next destination. It’s always through a coincidence of near-term objectives that the party members stay with each other—Estelle forming a party with Yuri through a coincidence of the path Flynn and the aque blastia thieves take, Karol heading back to the Hunting Blades in the same direction as Yuri following the aque blastia’s trail, Rita deciding to come along to the next town in order to investigate its blastia—until there’s enough of a “critical mass” of coincidence in their journeys for them to begin defining and articulating reasons to stay together as a group rather than individuals in constant conjunction.

In Heliord, Karol quietly asks Yuri if he’d like to start a guild with him, sowing the seeds of Brave Vesperia.

Once the party finds Flynn—not just the object of Estelle’s first mission, but also a representative of the Imperial Knights, the enforcers of order across the empire—they begin to take account for the paths on which they’ve sent themselves, deciding and articulating how to square their inner desires with their actions in the world. In Capua Torim, Estelle asks Flynn for permission to stay with Yuri rather than return to Zaphias; in Heliord, retrieved from Caer Bocram by Cumore and Schwann’s Knights, Rita uses her affinity for blastia to save human lives, Estelle uses her healing artes to save Rita, and Karol digs himself out of his depression over the Hunting Blades and Nan rejecting him to meekly ask Yuri whether they might someday start a guild of their own. It’s with this newfound coordination between desires and future courses of action in mind that the party is able to vocalize what they positively want to do next when issued orders by Alexei, following the events at Heliord, to investigate the aer krene at Keiv Moc:

- Rather than pursue her work as an imperial blastia researcher, Rita vocalizes that “if Estelle is going back to the capital, I want to go with her,” a sentiment that aligns not only with her suspicion of Estelle’s connection with the Rizomata Formula, but also with her growing affections for another person rather than a blastia: a person who’s willing to risk her life to protect and heal Rita.

- Rather than return to the Zaphias, Estelle, upon hearing Alexei’s order for Rita to explore the Keiv Moc, insists that she join Rita in Keiv Moc since “[her] healing artes would prove useful,” as they did with the Great Tree of Halure and protecting Rita from the out-of-control blastia in Heliord.

- Yuri accepts Estelle’s request that he accompany them in order to make the empire feel comfortable with its princess traveling to a dangerous place—choosing to stay with the group despite the fact that Alexei asks that he do so “only because you once sought to join the Imperial Knights,” the role which Yuri had previously defined himself by rejecting in favor of anything else.

Now, from beginnings in quests decided by what they don’t want, our heroes are ready to start recognizing and articulating their desires, those ends which they do want. Remember, however, that we’re tracing the symbology of a sword, and for all its influence in the story, Dein Nomos barely makes an appearance in Tales of Vesperia’s first act: we see Duke using it to “[slice] through the aer” in Keiv Moc, calming the aer krene while explicitly refusing to provide background context on it (“What good would that knowledge do you?”, he asks Rita when she wants to know how he was able to use his sword in this way), and Ragou wistfully invokes its name—the name of a principle at which he never arrived—when Yuri slays him. These characters don’t sufficiently understand the dynamics of their world to coordinate their desires into a principle that can legislate their activity and reshape the world as a law; short of the contextual clarity to do so, their desires only fashion them into well-animated pawns for those who do understand the wider machinery according to which the world’s factions interact.

On this reading, it’s no coincidence that the party begins to find its desire-based footing in the first act in the midst of an assignment by Commandant Alexei, the very same puppet master who uses the twin antagonists of Vesperia’s first act, Blood Alliance leader Barbos and Imperial Councilman Ragou, in the unwitting construction of his own Dein Nomos, his own will to power.

Alexei sets in motion the party journeying to Keiv Moc together from Heliord.

Like the party, Barbos and Ragou articulate and pursue their own desires, only to inadvertently serve Alexei’s ends for lack of coordinating their actions beyond themselves. The two conspirators are portraits of myopic men blinded by ambition, putatively leading organizations yet isolated in the pursuit of their missions. Barbos is the head of one of the five master guilds in the Union, yet he stands alone atop his Tower of Ghasfarost, a testament to his hubris, with a sword and blastia he expects will grant him the power to kill Don Whitehorse and take control of first the guilds, then the empire, and finally the world—with no clear path from one point to the next, besides faith in his own power and desire for domination. Ragou, meanwhile, seeks merely to manipulate the weather of his own little corner of the world, Capua Nor, in order to prey upon his townspeople as a means to “enjoy [him]self” and “dispel [his] boredom” as a councilman, conspiring for the sake of nothing beyond his own desire.

That Barbos and Ragou scheme with each other to achieve these ends with an agreement of “mutual non-interference” explicitly in place underscores how unable and unwilling they are to coordinate with each other for the sake of a mutual end. This isolation makes it child’s play for Alexei to use them for his own purposes: destabilizing the council in order to reinforce the authority of the Knights, and using Barbos to design and contribute to the network of blastia underpinning Alexei’s plot to forge his own Dein Nomos and seize control of Zaude.

Without coordination between the antagonists’ desires, it’s easy for Alexei to insert one of his enslaved agents—Yeager, with a blastia heart animated by the Commandant, and his Leviathan’s Claw guild—into their midst to coordinate their actions on Alexei’s behalf without their even noticing, since they aren’t sufficiently aware of the context in which they exist in order to recognize what such coordination looks like. Without coordination between the protagonists’ desires, it’s easy for Alexei to insert one of his enslaved agents—Captain Schwann, with a blastia heart animated by the Commandant, in the guise of Raven—into their midst to coordinate their actions on Alexei’s behalf without their even noticing, since they aren’t sufficiently aware of the context in which they exist in order to recognize what such coordination looks like.

Alexei calls on Captain Schwann after sending the party to Keiv Moc.

Blind to the system within which their own desires are expressed, it’s as simple and unceremonious for Barbos’ sword to be neutered by Duke and the actual Dein Nomos as it is for Lydon to be swallowed up by the Eye of Atamoni. This public act of a law, the principle of Duke and the Entelexeia’s will, wiping clean the senseless ambitions of a directionless leader suffices to eradicate not only Barbos, but also, effectively, the Blood Alliance, the guild saddled with that senseless leader and his lawlessness. In contrast, a confrontation between two insufficiently articulated desires—Ragou’s desire for sadistic self-satisfaction, and Yuri’s desire to see him punished in a way impermissible by the empire—can only conclude with a clandestine act under the cover of darkness, Yuri’s extralegal execution of Ragou, effecting no broader change in the nature of the council, the empire, or the global ecosystem in which they are embedded.

With these two villains gone, our heroes are free of their inertia, but in its place, they’re left with a newly formed guild bearing neither a name nor governing principles, a princess whose healing powers earn her the title of an “insipid poison of this world” by a yet-unidentified Phaeroh who offers no further context or explanation.

To shape the future through their individual principles of will, Yuri and his friends must learn how to organize their actions into an expression of will that can impact the world beyond themselves.

Estelle resolves to learn enough about the world to situate her newly awakened desires within it, following her encounter with Phaeroh.

We’ve begun the process of forging two swords with which to enact a future on the basis of our individual volition, but only just: the Swordians haven’t been honest about their nature, and Dein Nomos has barely shown itself, let alone presented itself as a tool to be used or understood by the party. Two groups have found their way out of inertia by learning to act instrumentally, whether ordered by others or themselves, and to discover their internal interests along the road; in order to transition now from honoring their authentic feelings to shaping the world beyond themselves, they need a reason and vantage point from which to interrogate how their personal desires relate to those of the others who came before them and who stand beside them.

Act 2: Through Betrayal, Resolution

You cannot grasp the impact of your desires until they publicly conflict with those of someone you trusted.

Leon reveals himself as a traitor and Hugo as the mastermind of the events in the first act of Tales of Destiny.

Tales games are known for their sympathetic portraits of complicated traitors, and Tales of Destiny and Tales of Vesperia illustrate how betrayal can be a surprisingly empowering force in helping individuals discover the contours of their own volition—how to take up a sword as a tool of projecting your values beyond yourself for the sake of creating a different world. Once Stahn, Yuri, and their friends experience how the actions of those inside and outside of their group can distort, co-opt, and reinterpret their own actions, they also discover how they can shape their wills to have a positive and additive impact on those beyond themselves.

Tales of Destiny: Reading a Marionette’s Strings as Information

The difference between destiny and self-governance is a choice in how to relate our actions to those of the past, and that choice is a privilege only possible when the past’s impact on us is laid bare for all to see.

The Swordians confess their deception to their masters after the return of the Aeropolis.

After Leon submerges the Swordians’ consciousness with his trick of the Aura Discs, Act 2 of Tales of Destiny opens with the revelation of that betrayal laying the foundation for the party to better understand their personal relationships with the present and the past. The characters have the opportunity to bear witness to the lives and connections the others have chosen—not out of inertia, but out of the clarification and vocalization of values they underwent in the game’s first act:[6]

- Philia finds Stahn home in Lienea with his sister and grandfather, living a quiet country life.

- Stahn and Philia witness Rutee caring for the children at the orphanage she sought to protect in Cresta.

- Stahn, Philia, and Rutee see Garr assuming the role of King of Phandaria following the death of his father, presiding over a restabilized kingdom from his throne.

- Mary is readjusting to life with her memories and her husband, Dalis, after finding him in Phandaria, overcoming the amnesia he’d imposed upon her to protect her, and freeing him from the yoke of Lydon’s mind control.

Even before Hugo reveals his intentions and the Swordians confess to the party about their true mission, these tableaus show that different individuals are called to wield the tools of the past in different ways, and that it remains their choice to answer this call. When Stahn and Philia see Rutee happily presiding over the orphanage, they both feel that it would be best to let her stay in Cresta rather than asking her to rejoin them, whereas Dymlos and Clemente insist that, as a master, her service is necessary for the group to combat the catastrophic threat of the Eye of Atamoni; when push comes to shove, though, Rutee is adamant that only she can decide what’s the right thing for her to do—and that she feels more at home traveling with her friends than at the orphanage, especially if she can do so in service of saving the orphanage from destruction at the Eye of Atamoni.

Rutee asserts her right to participate in the party’s journey for her own reasons, interrupting Stahn, Philia, Dymlos, and Clemente’s debate about whether to take her with them to Seinegald.

At this stage—with the Eye of Atamoni back in play and the Swordians insisting on their knowledge of its danger from 1000 years ago—the heroes are in a position to understand that they are being called back to deal with some kind of history. They’re no longer muddled in the toxic timelessness of Lydon’s struggle, understanding now that this has more to do with the Eye of Atamoni than him or any present-day actor per se, but the relationship between past and present remains opaque: Why is the Eye of Atamoni back? What is the Swordians’ relationship with it? Their choice, then, is one to confront history whatever it may bring, for the sake of improving the present and everything they care about. The Swordian masters reuniting with each other in their home environments allows them not only to make that election individually, but also to see and support each other’s reasons for making the same election.

Mary, meanwhile, makes a structurally analogous decision to wrestle with and interrogate her own past, now that she has rediscovered it—a decision that leads her to refuse to come with Stahn and the others as they are recalled to Seinegald to deal with the Eye of Atamoni because the past that is relevant to her calls her to a different present-day principle of will than that which the masters take up.

During the regrouping of the party following Hugo and Leon’s theft of the Eye of Atamoni, Mary rejects rejoining the group in favor of engaging with her own, newly discovered past and relationship with her husband.

The honest rediscovery of the masters’ native contexts as separate from the Swordians is a prelude to discovering a tragically inverted state of context in the treachery of Leon and Chaltier, Hugo’s marionettes. Where Stahn, Rutee, and Garr are Swordian masters who exert their own agency and chosen roles over their home lives—Stahn being a supportive big brother to Lilith, Rutee acting as a kind of surrogate older sister or mother to the Cresta orphans, and Garr ruling his family’s domain—Leon is a tragic shell of a “master” forced into a role by a manipulative and artificial conception of his home manufactured by Hugo, his own father, and Marian, a hapless housemaid whom Hugo brought into the household because she resembles Leon’s deceased mother. Stahn and his friends’ newfound sense of fulfillment in their place in the world is counterbalanced by Leon’s imprisonment in a home that’s completely predicated on treating people as tools: as the President of Oberon Corporation, Hugo is an expert at using people instrumentally to advance his own agendas, whether that’s coordinating international trade for the bottom line of his company, guiding Lydon’s machinations to put the Eye of Atamoni in motion, or threatening his housemaid to secure his son’s cooperation in manipulating our heroes into getting that Eye of Atamoni into his hands.

When the party confronts Leon beneath Libra IV—the secret, recommissioned base of his father’s company—he reveals himself not just as a traitor, but specifically as a kind of “anti-Swordian master,” clarifying the importance of the masters and Swordians’ own growth by showing them how deleterious the opposite dynamic is. Where the Swordians represent those with a purpose in the past acting as tools to enable their masters’ new principles of actions in the present, Leon is made into a tool for someone else’s ends by being bullied into a subservient relationship to his own past. Where Lydon’s toxic zealotry was timeless, Leon’s enslavement by Hugo perverts relationships between past, present, and future: Chaltier, his own Swordian, is entirely submissive to the will of his “young master” in the present, while his Swordian comrades hold fast to their true mission from the time of the Aeth’er Wars; back in the first act of Tales of Destiny, we now understand, Leon pulled the strings of the party using Hugo’s electric tiaras to keep them bound to Hugo’s vision of the future rather than anything to do with their present-tense goals.

Entirely robbed of the ability to determine the context motivating their actions, all that remains for Leon and Chaltier alike is to lapse into a purely defeatist form of fatalism: not a prudential lie about destiny to empower others of the sort that characterized the first act, but rather the resignation and self-abnegation at the heart of the only two sentiments Chaltier utters to to the Swordians—or to anyone for the remainder of the story—after the party has learned of his betrayal: “it’s out of our control […] You should acknowledge the fact that it is useless to go against the ancient ways.”

Leon’s Swordian, Chaltier, expresses the fatalistic perspective that subjugates him and Leon to Hugo’s machinations.

The revelation that Rutee is also Hugo’s child—a revelation which Leon hurls at Rutee like a knife meant to fatally wound her before the battle has even begun—is a devastating discovery for Rutee, but it also poses a clear and present danger to the Swordians. Leon is a living testament to how thoroughly these corrupted networks of influence can co-opt not just an agent, but a Swordian and its master, specifically. Without an explicit demarcation between the agents of the past and the agents of the present, those agents can be so completely dislocated as to completely lose the will to govern themselves at all. If Hugo could achieve this with his son—a son who recognizes himself as “merely a disposable tool” to his father—one might worry that there would be little to stop him from repeating the process with respect to his daughter, replacing his current tool once the heroes “dispose” of it. Atwight seems to recognize this risk immediately, calling out to Rutee that Leon’s claims about her lineage are “nonsense” and ordering her not to believe him; it’s this same recognition, I think, that explains why the Swordians quickly become more honest with their masters once they defeat Leon and witness Belcrant and the Aethersphere rising, evidence of how high the stakes of Hugo’s mind-games are.

Atwight expresses the Swordians’ collective fear of the past reasserting itself in the present following the advent of the Aeropolis and Belcrant.

In the face of the revived Aetherian homeworld, the Swordians confess what their true purpose has been since they first found their new masters, acknowledging not only their own deception but the contributory role their deception played in Leon’s manipulation of the party:

Dymlos: “At the end of the ancient wars, when we were about to enter our sleep… We were given a mission.”

Clemente: “We were ordered to destroy the Eye of Atamoni so that Dycroft could never be restored.”

Atwight: “Ever since we were reawakened, our intent was to destroy the Eye of Atamoni. As a result, we ended up deceiving you all…”

Dymlos: “But Leon was aware of what we were doing. And he led us around by the nose. At this rate, the surface will be totally destroyed by Belcrant.”

This explanation sets the tone for the rest of Act 2: to overcome the risk of the temporal perversion that swallowed Leon, the Swordians and their masters both accept more personal responsibility in actively vocalizing the contexts within which their lives and principles of will are embedded. On the Swordians’ part, this consists in helping their masters to reach and overcome Hugo by introducing them to the history, characters, and actual machinery of the Aeth’er Wars that spawned them in the first place:

- They introduce their masters to the digitized personality imprint of “Marius Raiker, commander of the Er’ther forces during the Aeth’er Wars.”

- They band together to revitalize Radisrol—now reinterpreted from the mysterious, Atlantean city in which Clemente called out to his “destined” user, to the Er’ther Aeropolis in which an ancient army ascended to the sky to finish their oppressors once and for all—in order to reach Hugo and his brood, entrenched in their mausoleum of a sky fortress.

- Igtenos, that same Swordian whose damaged, non-sentient form symbolized the inability of Lydon to grasp the distinction between present and past, now must be revived by his comrades and their masters specifically for his expertise from his own, past context as an expert in high-energy physics, so that he can help the party in their present-day context of reaching Hugo in Dycroft, protected by a Mirror Shield.

Igtenos immediately apologizes to Garr upon being revived in Helraios.

As in Tales of Destiny‘s first act, Igtenos is a telling marker for the group’s progressive development. When Garr and his friends revive the Swordian in Helraios on the way to Dycroft in the Aethersphere, Igtenos’ first reaction is to apologize to his master for failing to protect his father from Lydon, the usurper. Garr, the ruler, is able to take responsibility for the burdens and failings of his kingdom in the present, absolving Igtenos of his guilt and inspiring him to do the job that only someone with his expertise from the past could do: the job of undoing a magical barrier that’s of a piece with Igtenos, another object of the world’s past.

Suppose, like the Swordian masters—like Leon, like Garr, like Rutee—you discover that your world and your capacity to act within that world—the very sword by which you enact your will—are contingent upon agents and events from the past—a mother whose legacy is manipulated by your father, a war whose leaders left the central conflict unresolved to fester over centuries. At that moment of discovery, you find yourself to be a marionette, your limbs animated not by your own volition, but rather by a set of invisible strings, the ghost of something that ought not to exist in your present context. Once you see those strings, you have two options: you can interpret your own agency as impotent and fully surrender to the whims of the hand pulling the strings, as Leon does with Hugo, or you can take those string as an expression of information about the connection between you and someone beyond yourself, and use that information as an opportunity to communicate with the hand on the other end, allowing both the marionette and hand to act better in concert with each other according to their own intentions, as Garr does with Igtenos.

The marionette model of discovering one’s volition in Tales of Destiny. (Source.)

This clarity of communication allows the masters to ascend to the upper echelon of the Aethersphere of their own accord with the support of the Swordian’s full knowledge and practical facility with the past, reenacting the Er’thers’ ascension in Radisrol for their own, modern reasons. Nowhere is the human impact of this growth more poignant than in the case of Rutee gaining the depth of insight her tragic brother could never access, allowing her to see Marian’s relationship with him more holistically than Marian and Leon can—and to call her father back from oblivion in his final moments.

Rutee takes Marian to task for mischaracterizing Leon’s feelings for her.

After the party defeats a maddened Rembrandt in Mikheil, Marian, his hostage, mourns the death of Leon, lamenting that she “couldn’t do anything for him. He died without knowing what true kindness meant […] [H]e didn’t really open his heart to me. He only opened himself to a shadow of his mother.” Rutee confronts Marian with the bluntness and incisiveness only available to a sibling of Leon’s who escaped his fate: she tells Marian flatly that “Leon is dead” when Stahn hesitates to say anything and Philia wants to hold on to the unreasonable hope that Leon survived his confrontation with the party beneath Libra IV; when she hears Marian’s lament, she immediately rejects Marian’s despairing point of view, yelling at her that Leon sacrificed his life for hers: that Marian was someone whom Leon loved, not “some kind of tragic heroine, and that, if Marian “really love[d] Leon,” she must honor those feelings in order for Leon to be able to rest in peace.

For those whose lives and actions have been hijacked by puppeteers with agendas reaching backward into the past, the submission to the strings that guide their actions is total: even the emotions they might feel are interpreted as superficial artifacts of the puppeteers’ actions, from which the marionettes themselves can derive no value or sense of personal identity. Thus we saw Leon, all the way back on the party’s return voyage from the battle against Lydon, rejecting Stahn’s gesture of friendship when Leon is airsick on the Draconis, exclaiming that he doesn’t have friends and adding the fatalistic perspective of a broken marionette moments later: “Let me tell you something,” he tells Stahn: “People will deceive you no matter how much you trust them!” Thus, too, we see Marian describing Leon as someone who chased a shadow, robbed of the experience of true kindness. Yet for Rutee, who has undergone the growth of (1) appreciating others’ utility as a means to their own ends and (2) understanding Atwight’s mission and reasons for withholding Rutee’s own history from her, the influence of the past has no power to nullify the emotions and intentions of the present. Once the relationships between Leon Magnus, Chris Katrea (his birth mother), and Marian are clarified, it’s perfectly consistent to acknowledge the resemblance between Chris and Marian according to which Hugo was able to make Leon his pawn, while also validating the feelings which Leon and Marian have for each other as individuals sharing a home together in the present tense.

When all is said and done, the tragic difference between Rutee and Leon is that Rutee has the privilege of being able to develop in a group of humans and Swordians who empower her to reconceptualize her manipulative tendencies as a lens through which to relate and support the autonomy of herself and others, whereas Leon remains sealed within a prison in which he is governed by the most instrumentalist mastermind in the world, leaving Leon to treat his own manipulative tendencies—perhaps a family trait between Hugo, Rutee, and Emilio—as a method of reinforcing the same, all-encompassing machine in which he’s been taught to see himself as a cog.

Gripping the Swordian “Berselius,” Hugo offers what he calls a “premonition” in the form of an invitation for the party to join him in creating a new utopia, divorced from the past.

By understanding the distinction between past and present agents and reasons for action, Rutee, Atwight, and their friends can overcome the instrumental manipulation that bound them in the first act and bound Leon from birth to death; absent Lydon’s toxic timeliness and Leon’s temporal perversions, our heroes are in a position to evaluate their actions in terms of ideals which they wish to impart upon the world’s global community. Accordingly, in their journey through the Aethersphere following Leon’s betrayal of the party and self-sacrifice for Marian, the party engages in philosophical debates with Hugo’s acolytes who sincerely believe in his vision for the world’s future, rather than those who served his purposes unwittingly or against their will. Oberon Regional Managers Ilene and Baruk—the kind-hearted confederates who kept the party on Hugo’s intended path for them during their pursuit of Lydon—now both reveal themselves as disciples of Hugo in every sense, advocating that the only way to cure the personal and societal ills of the world is to “start all over again” (in Ilene’s words), in “a true utopia” made possible by Hugo “harnessing the Eye of Atamoni’s power” to “transform himself into a superior being,” governing a new world order as a god whose “motives are not clouded by his ego or any hidden agendas” (in Baruk’s words).

Whereas Lydon, a priest presumably isolated from the outside world through his practice in the Straylize Temple, was so consumed by his ego as to enact a scheme of world domination that offered no rationale to justify itself, Ilene and Baruk, Oberon operators deeply embedded in their regional communities, have robust, justified perspectives on why the world is “suffering from a disease” and therefore needs to be reshaped. In Stahn and his friends’ his journey around the world in pursuit of Lydon, both Ilene and Baruk endeavor to give them quietly curated windows into those experiences that inspired their ideals:

- Ilene takes Stahn on a one-on-one date, showing him around Neuestadt, sharing with him its history of having “lost something important” as its natural environment was exploited for the sake of societal progress. During their day together, she meticulously tailors their progression from a serendipitous, intimate moment of sharing a couple of popsicles together to wandering into Neuestadt Arena and being berated by the champion, Khang, for the sake of sport and human entertainment.

- Baruk’s legacy precedes him: the party learns about, and sees the influence of, “the Baruk Fund” before they meet Baruk himself as he legislates from a building designating the “Baruk Fund Office” (whereas the party interacts with Ilene in a Lens Shop and her family mansion). The Baruk Fund is an institutional embodiment of Baruk’s will, “a non-profit foundation established by Baruk to focus on charitable activities,” supporting “orphaned children” and “sen[ding] donations for disaster relief,” all for the purpose of “helping the weak [for the benefit of] society,” in a world which Baruk sees as suffering from self-destructive factionalism across the course of history—particularly, in a corner of the world, Calvalese, which the party witnesses as plagued with xenophobia that’s been entrenched in its communities since the aftermath of the Aeth’er Wars, at which time the surviving Aetherians were sequestered in that unlivable desert continent and “systematically discriminated against for countless years.”

Hugo calls to his “four generals”—Leon, Rembrandt, Ilene, and Baruk—to commit themselves to him in changing the world “for true peace to reign supreme.”

Ilene and Baruk jointly illustrate how well-intentioned people can be misled into sacrificing their free will in the service of an apocalyptic idealism from diametrically opposed perspectives: Ilene from disillusionment with individuals, and Baruk from disillusionment with society. As Ilene shows Stahn a personal connection and portraits of individual life within Neuestadt, so she laments as an antagonist in the Aethersphere that “Countries, kingdoms… they’re not important at all. The most important thing is what’s inside people’s hearts:

You should have experienced things like suspicion, hatred, discrimination, and calculated kindness during your travels… I’ve had enough of this world! There’s no choice except for us to start all over again.

Further on in the Aethersphere, when Philia tries to convince Baruk of humanity’s potential to band together and improve, he rejects her individualistic perspective in favor of the macrocultural perspective that inspired his non-profit Fund in the first place: she tells him that “[p]eople are capable of understanding each other and working together towards a common goal,” and he counters that “That might be true among individuals, but it’s not necessarily true if we looked at society as a whole. Look at all the social ills that plague this world […]:

It is impossible for mere mortals to achieve order and perfection. […] Didn’t you experience Lydon’s rebellion first hand? […] It’s not just him. His followers like Batista and Tiberius as well. There are plenty of fools like that in the world. […] [D]on’t you feel that senseless destruction and chaos should be avoided at all costs? Every time someone like Lydon appears, many lives are sacrificed.

Coming from these two perspectives of personal failings and societal inadequacies, Ilene and Baruk arrive at an ideology to which they are willing to sacrifice their individual volition completely: Ilene “belong[s] to Oberon Corporation [and] can’t disobey Hugo,” and Baruk “has no choice” but to obey Hugo’s orders, to the point that “that man [who Baruk formerly was] no longer exists”—both individuals subsumed by Hugo, but not for a lack of conceptual distinction between past and present, as was the case with Lydon. Rather, Ilene and Baruk see the present state of human nature and the culture within which it exists as irredeemably self-destructive, preventing the peoples of the world from progressing over any time horizon. This kind of pessimism is like a lock joining with its key: far from being ahistorical, Baruk sees the long arc of history poisoning entire continents like Calvalese, and Ilene sees the corrosive emotions of human life stoked by these circumstances, corrupting those who could otherwise do good in the world. When the present and past offer only confirmation of negative outcomes rather than a blueprint for progress, the only model for change appears to be a clean break, fully rebirthing society under the governance of a god rather than its own agency; to this model, Ilene and Baruk surrender themselves.

In Cloudius, Baruk commends the party’s optimism at the end of their debate about the nature of social progress, just before they come to blows, unable to resolve the difference between their views.

Of course, pessimism isn’t the only ideology at which one can arrive after experiencing the people of the world and their relationship to history: its counterpart, which both Ilene and Baruk explicitly recognize in the party, is optimism, the belief that it’s possible for enough people to collaborate in pursuit of a better future and overcome the patterns of the past, be those patterns interpersonal or international. In the wake of her confrontations with Leon, Atwight, and Marian, it’s a foregone conclusion for Rutee to not only reject but even revile Baruk, a man whom she once admired, from a place of optimism in the face of his resigned, utilitarian pessimism: she has the self-awareness to admit that at the beginning of her journey, when she saw people as tools to be used, she held up Baruk as a paragon of someone who used his own means, and the means of those within his domain, for reasons that resonated with hers, like helping orphans; but she has also evolved to the point that she now recognizes the final conclusions of Baruk’s method as monstrous, and that the true ideal by which one govern’s oneself ought to be an end to tragedy for all those among the living:

Rutee: I always thought the world was full of worthless people… Then there was someone like you… someone who I thought I could respect… I can’t forgive myself for ever thinking that way about you.

Baruk: You sound as if you’re against everything I stand for. Remember, judging people while you’re emotional will cause you to make serious mistakes.

Rutee: I just want to prevent any further tragedies.

Similarly, Stahn’s unshakable faith in the simple ability for people who care about the world to work together for the better is something that the pessimistic Ilene decries as “impossible,” so opposed as it is to her view of the human condition—though she quietly, hopefully, recognizes that a world with more people like Stahn might be able to turn his dream into reality.

Stahn reflects with Rutee on the nature of the “optimism” Ilene identified in his approach to his journey.

We’ve identified the symbology of the Swordians as representing conflicts from the past empowering new principles of action in the present. In Tales of Destiny‘s first act, these living swords showed their users how to wield a sword, take up a desire with which to orient their actions at all, absent the temporal demarcations required to understand where the tool’s purpose ends and the user’s begins. In this second act, the revelations of treachery and manipulation are a tempering fire for the swords, putting their origins and designs into finer definition, and thereby empowering their wielders to more precisely define how they want to use that specific object from the past to impact themselves and their fellows in the present world. This distinction of past and present between tool and user effects the transition from an isolated, instrumentalist worldview with no room for autonomy to an idealistic worldview in which agents can articulate what kind of change they want to bring about in the communities to which they belong.

Instead of looking inward to discover their desires and then inhabit their desires in their home environments, they now look outward to unearth the shape of their intended impact, a process best realized through a combination of (1) clashing with differently-minded idealists and (2) deliberating with like-minded idealists. Stahn asserts his “naive” optimism to Ilene, who wants to believe him yet doubts the capacity of humankind, and then, after the battle, Stahn speaks with Rutee, Atwight, and Dymlos, helping the masters to determine the impact they want to have on society’s future as the output of their unique journey to use the Swordians in the Swordians’ own mission to destroy the Eye of Atamoni: they “don’t think our world is something you throw away,” yet they help the world not by thinking about “stuff like ‘the world'” in an abstract way—rather, they do so by “fighting to protect the people who are important to [them].” This mode of cherishing the world by virtue of cherishing those within it gives them a different understanding of their historicity—how their actions in the present stand in relation to those of the past and future—than Hugo, who would schematize everyone within this ideal of erasing the world’s present and past in favor of a discontinuous future.

Hugo stands before the party basking in the power of “Berselius”—in fact, Kronos, leader of the Aetherians, masquerading as the ancient Swordian hero.

The tragedy of Hugo is also the lesson of why the party’s idealism is insufficient to determine the world’s future course through their individual volition. Hugo, like the party of Tales of Destiny‘s second act, understands enough about the past and present states of the world to wield a sentient Swordian (unlike Lydon), articulating and enacting an ideology through his blade. Yet the substance of Hugo’s ideology reads as a total refusal to process the past: rather than work with the people of the world to understand how the legacy of the Aeth’er Wars and its wounds have shaped their world, helping to chart a course to heal those wounds, Hugo’s raison d’être is to erase all of civilization, all of history, in favor of a fresh start governed solely by his will.

The instructive irony is evident: those who reject the past are dominated by it. Hugo’s will is puppetted not by Berselius, but by Kronos: the ancient leader of the Aetherians from the time of the Aeth’er Wars; the despot whose only agenda is to finish the conflict in which he was embroiled 1000 years earlier.

Hugo, finally released from the grip of Kronos, calls out to his daughter, in hopes that an intimate moment with her might be his final moment.

Even if we understand the difference between our actions and those of the past, unless we fully address the conflicts of the past and put them to rest within their native context, their influence will bleed through and constrain the desires, intentions, and choices of everyone in the present. Without addressing the past, all we can do is grasp for meaningful moments with good intentions in a kind of mindless presentism—as poor Hugo did when he had one fleeting moment of clarity in which to push Rutee and Atwight away from him, to Cresta’s orphanage, before losing any capacity for volition whatsoever; as poor Hugo does when he reaches out to see his daughter’s face one final time for a moment of true happiness as he lays dying, finally freed from Kronos’ puppetry. Kronos’ revival demonstrates that this danger is just as pressing for our heroes as it was for Hugo: the masters may understand their desired future, but without addressing and helping their Swordians to fully put their past—and, by extension, themselves—to rest, their actions amount to little more than a recapitulation of a war from 1000 years ago.

To shape the future through their individual principles of will, Stahn and his friends must learn how to inter their tools within the forges whence they came.

Tales of Vesperia: Discovering Your Group’s Principles by Learning What It Means to Betray Them

When you form order out of chaos, you need to witness that order breaking before you understand what holds it together.

Don Whitehorse charges all those in Dahngrest, including our heroes’ party, to make the world’s new age for themselves—his final words before dying as recompense for the death of Belius.

As Yuri, Repede, Estelle, Karol, Rita, Judith, and Raven set out from Dahngrest followed the deaths of Barbos and Ragou along with the visitation by Phaeroh, they’re no longer following instrumental missions to recover a blastia or find a Knight: now, they’re on a mission to understand the world and their places in its networks of communities in order to have the epistemic standing to coordinate groups that can impact the world according to the groups’ desired outcomes. A consequence of this new resolve is that the outset of Tales of Vesperia‘s second act is itself more chaotic than the first act, and diametrically opposed to the outset of Tales of Destiny‘s second act: where Stahn and his friends progress from attuning to their desires at the end of a fetchquest to expressing those desires isolated from each other in the presentism and simplicity of their homelands, Vesperia‘s party sets out with a newly-formed guild that lacks both laws and a name, encountering a wide range of communities under the influences of leaders with agendas bearing no obvious connection. While Barbos and Ragou were unwitting pawns of Alexei in Act 1, they both bore a clear connection to the party’s quest to reclaim the aque blastia and reunite with Flynn, preserving the player and party’s sense of narrative continuity from one town to the next; now, in pursuit of Phaeroh and Estelle’s “destiny,” the party bounces across self-contained portraits of Cumore’s oppressive regime in Heliord and Mantaic, the Flynn Brigade and Hunting Blades’ occupation of Nordopolica, Duke’s respite in a projection of the ancient Yormgen, and Yeager’s antics in Heliord, Nordopolica, and the Weasand of Cados.

The signal within all of this noise only becomes clear once the party learns how to convert its desires into constraints on their group’s collective will: something that is only possible by witnessing the death of a man whose will superseded that of the very Union for which he stood, and finding within his legacy a method for holding their own members accountable to the group’s laws.

Karol reflects with Yuri on their decision to start a guild prior to deciding what it stands for.

The end of Act 1 showed Karol and Yuri’s decision to start a guild based on Karol’s desire to do so, with neither a name for the guild nor laws for its members to uphold. They begin Act 2 by putting laws and a name to their fledgling guild, without understanding what it really takes for the guild to collectively advance an agenda based on its laws. In large part, this second motion of Tales of Vesperia‘s story—the movement in which its characters must refine their desires into publicly accessible principles of action to which communities can subscribe—is the story of Brave Vesperia learning the difference between the solipsistic enactment of a principle in private, incommensurable ways by the members of a group, and the coalescence as a group behind a unitary, publicly determined course of action.