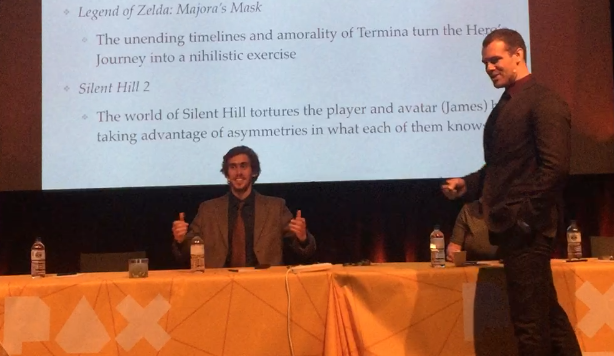

After With a Terrible Fate connected with the good people of Zelda Universe at our PAX South 2018 panel, “Which Games Belong in the Video Game Canon?”, they asked to interview us, and we were honored to accept.

Dan Hughes (the seriesrunner of Now Loading) and I sat down with ZU’s Eduardo Hernández to discuss the origins of the With a Terrible Fate, the ins and outs of constructing a video game canon, and what you can expect from us at PAX East 2018 this coming week.

ZU: What started With A Terrible Fate?

AARON: I was fortunate to get the chance to study video games in high school: in my senior year, I proposed and conducted an independent course of study in which I analyzed how role-playing works in Majora’s Mask, Nier, Dishonored (in three parts here, here, and here), and Deus Ex: Human Revolution. This work evolved out of my long-standing interest in theater: I wrote, directed, and acted in plays throughout high school, and I had a hunch that video games had a way of picking up the art of storytelling where theater left off. That project was transformative: it proved to me that it was possible to study the stories of video games in an academic setting.

When I moved on to college, I forgot about video games for a while. Then, in 2014, I started studying philosophy at the same time that Nintendo announced its plan to remake Majora’s Mask for the 3DS. Dan, a friend of mine from high school, remarked to me that it was “the most important video game of all time.”

That remark stuck in my head—and, the more I reflected on my recent exposure to philosophy, the more convinced I became that there might be something philosophically interesting about the special way that Majora’s Mask tells its story.

I originally conceived of With a Terrible Fate as a way to prove that Majora’s Mask’s storytelling really was philosophically interesting: I spent three months—the time from the remake’s announcement to its release—analyzing virtually every aspect of the game’s story in an effort to better understand what makes it such a compelling work of art.

During those three months of analysis, I made two discoveries that shaped With a Terrible Fate into what it is today:

- It wasn’t just Majora’s Mask: video games as a medium were advancing storytelling in rich ways that weren’t yet (and still aren’t!) anywhere near fully understood.

- It wasn’t just philosophy: many academic fields of study had insights to share with us the special stories that only video games can tell.

In order to turn With a Terrible Fate into a space where everyone could analyze the storytelling of video games, I started publishing other people on the site as “Featured Authors”—starting with my friend, Nathan, after we had the good timing of spending spring break discussing video games together just a month after I finished my work on Majora’s Mask. The site also started analyzed games beyond Majora’s Mask (and beyond the Zelda franchise—sorry, Zelda Universe!), starting with my work on the role of the player in Xenoblade Chronicles.

Since then, With a Terrible Fate has become a team of video game analysts united by a single mission: to give everyone new tools for understanding and appreciating the storytelling of video games. We’re a team of 14-and-counting, and we’ve had the pleasure of discussing all sorts of games with all sorts of gamers—both online, and at conventions all over the world.

By the way, we’re nowhere near capacity: we’re still actively looking for passionate gamers and thinkers to join our team.

ZU: You frequently write about creating a video game canon, but the type of canon you write about is different than the type of canon that video game fans are used to discussing. Can you briefly explain the difference between the two?

AARON: I think that it was an important choice for us to have chosen the term ‘canon’ for our work, but it’s undoubtedly caused some confusion for the precise reason you raise in this question: it’s an entirely different use of the term ‘canon’ than what a lot of gamers are used to.

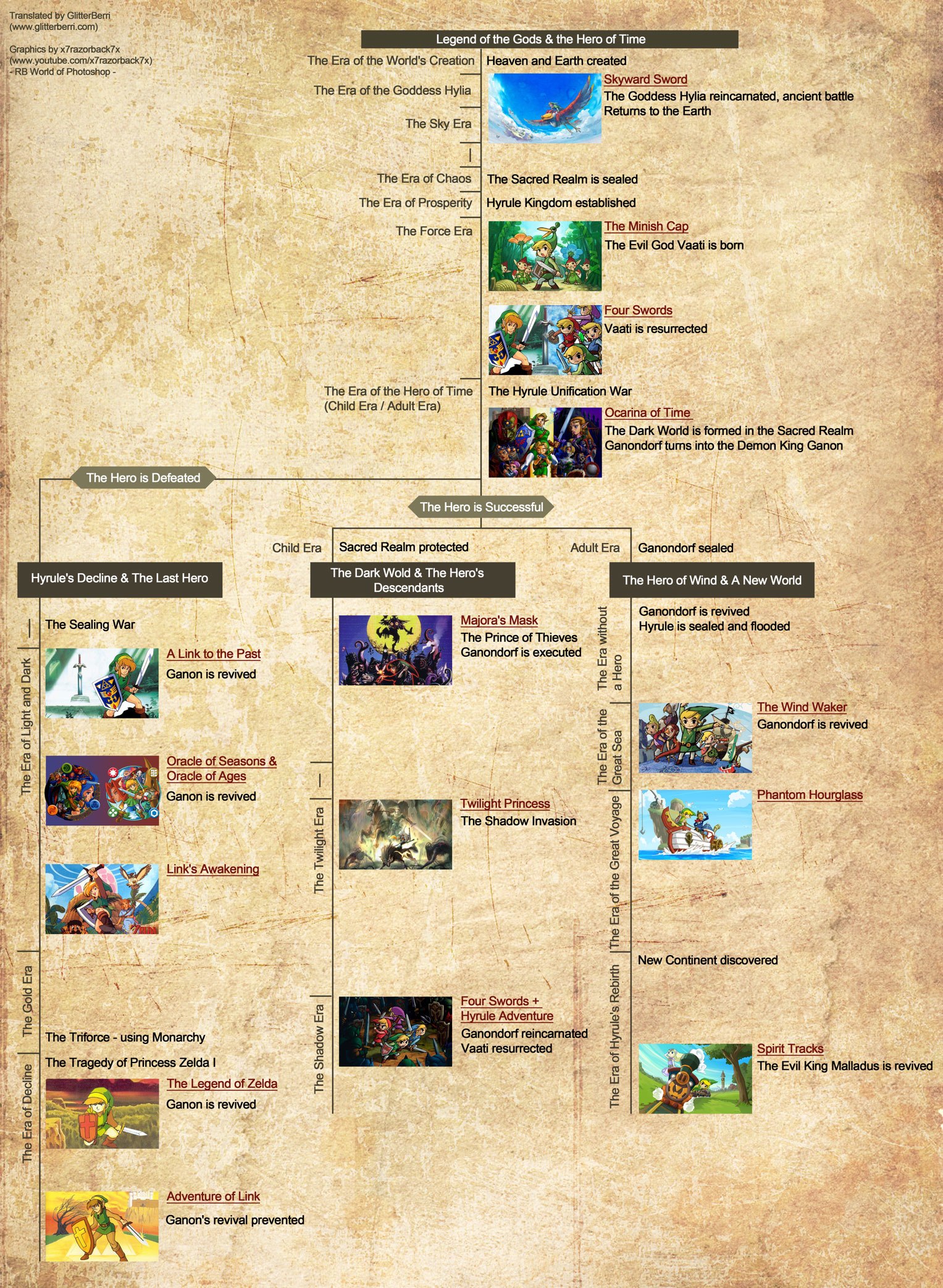

These days, people often talk about a canon of events: those events in a story or series of stories that have been “officially sanctioned” by the story’s creator. In this context, the “canonical” Zelda stories are those that have been sanctioned by Nintendo. With a Terrible Fate actually has a whole other series that’s centrally concerned with analyzing the canonical gap that exists in the Zelda timeline between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess—but that’s not at all what we’re talking about when we write about, as you say, “creating a video game canon.”

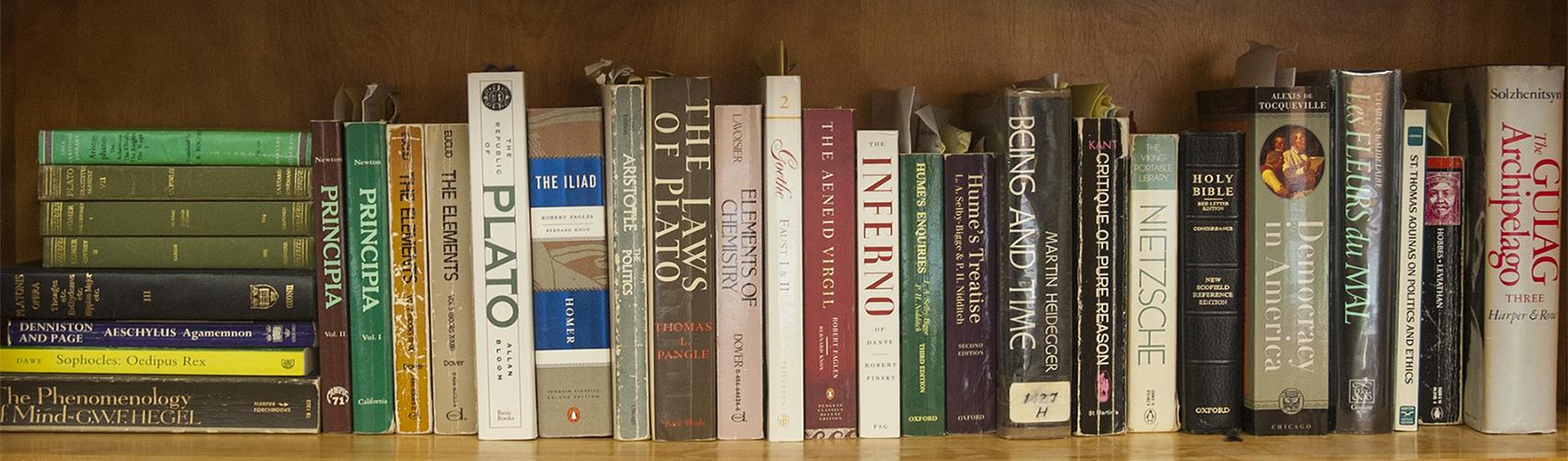

In our series, Now Loading… The Video Game Canon!, we’re concerned with a canon of works: a set of video games that have made seminal contributions to the unique storytelling abilities of video games. If you ever took a “Great Books” course in high school or college, you were probably exposed to this kind of literary canon—works like Oedipus Rex, The Divine Comedy, Hamlet, Ulysses… and so on. When we talk about creating a video game canon, you can think about it as constructing the syllabus for a course on the “Great Books” of video games.

So we end up getting a decent number of confused comments saying things like: “Obviously, Ocarina of Time is canon: it’s the basis for the entire Zelda timeline!” Of course it’s nonsense to ask whether an official Nintendo Zelda title is “canon” in the canon-of-events sense of the term. That’s not what we’re doing: we’re asking which video games have made crucial advances to the storytelling craft of the medium, and what exactly those advances were.

ZU: What are the benefits of establishing a video game canon?

AARON: At With a Terrible Fate, we feel that it’s important to think of “establishing a video game canon” as a particular perspective we can adopt in analyzing the storytelling of video games. We do believe that this perspective has distinct advantages over other common ways of discussing and reviewing games, but it also comes with distinct disadvantages. It’s important to see both the pros and the cons of this kind of perspective, and to decide with open eyes whether or not it’s worth adopting.

The major benefits of establishing a video-game canon are fourfold:

- It establishes reference points for better thinking about our relationship to video games as a medium.

- It gives us clearer, functional standards that we can use to better assess the quality of video games.

- It provides a more precise analysis of the special elements of video-game storytelling.

- It equips us with a better understanding of what video games can do as a medium that other storytelling media can’t.

Let me say a bit about each of these, in turn.

Reference points. At bottom, a canon—whether it’s a set of “Great Books” or a set of “Great Video-Game Stories—is a set of works that people can turn to as a tool for better discussing and understanding the subject matter of the canon. The works of the canon serve as reference points in three ways:

- They’re reference points in our conversations with others. When you discuss a particular game with other people, how frequently do you analyze the game by comparing it to other, “canonically successful” (or canonically unsuccessful) video games? “Breath of the Wild is like The Legend of Zelda meeting Skyrim.” “PREY is like SOMA meeting Dishonored, with just a hint of BioShock.” When we do this, we draw on a common knowledge base of just the kind that canonical reference points provide—the kind of knowledge base that colleges like Columbia University aim to impart to students by requiring them to take “core classes” that teach everyone the same set of canonical texts.

- They’re reference points for understanding our own feelings about video games. When I play video games, I often have a gut reaction of liking or disliking it, without immediately knowing why I have that reaction. When I want to know why I have those reactions, it’s natural to reference canonical games in order to provide context around why I might be feeling this particular way. “Why do I feel so cheated by Final Fantasy XIII-2? Maybe it’s because it featured many of the best elements of Chrono Trigger—a game whose storytelling I really enjoy—but it framed those elements with the story of an avatar who literally didn’t want to be in the game’s world or story.” A canon empowers us to make more robust judgments of every game we play much quicker than would otherwise be possible.

- They’re reference points for better understanding other works. If you try to start from scratch every time you analyze a video game, pretending as if it were the first video game to have ever existed, your process is severely limited: you end up having to reinvent the wheel in order to understand foundational storytelling elements like interactivity, choice structures, theming, and so on. In contrast, if you have a canon on which to draw, you can more clearly see how each new game is in dialogue with older games. Shakespeare didn’t write Hamlet in a vacuum: he was responding to classic literary works like The Oedipus Cycle and The Divine Comedy. Similarly, Okami didn’t appear out of the ether: it was engaging with a rich history that included both classical, mythological sources, and other games, like Ocarina of Time.

Functional standards. When most reviewers determine the quality of a new video game, they do so by rating it on a variety of features: features like “story,” “replay value,” “gameplay,” and so on. They’ll grade the video game on each of these features, and then they’ll average those grades in some way to determine the game’s overall grade.

I think this is a misguided way to determine the value of video games. The problem is that this kind of review fails to distinguish between the different functions a video game can serve. Video games can serve a variety of functions: they can be a medium for storytelling (that’s the function we care most about at With a Terrible Fate); they can be a form of entertainment; they can be a tool for learning new things; they can be a way of socializing with other people; and so on. To judge a game’s “overall quality” with a numerical rating is to ignore the question of what functional role we’re judging the game to have succeeded (or failed) in filling.

This matters because the factors that contribute to a game’s success in one functional role may be totally different from the factors that contribute to its success in a different functional role. To see this, consider an analogy: a knife, too, can serve a variety of functions. For instance, it can function as a tool for cutting things, or it can function as a ceremonial decoration. Now, a factor like sharpness might make a knife better at cutting—but it might make it much worse as a ceremonial decoration (maybe, for instance, you don’t want to use dangerous objects in your ceremonies, and sharpness makes knives dangerous).

So suppose that we’re considering a really sharp knife, and I ask you: is it a “good knife”? Well, based on what I just told you, you should tell me that the question I’ve asked you is incomplete: I need to specify whether I’m asking if it’s a good knife as a cutting implement (in which case the answer is “yes”) or if it’s a good knife as a ceremonial decoration (in which case the answer is “no”).

The kind of video-game review I’ve described is basically trying to answer the question of whether or not the knife is a good one, without specifying whether they’re evaluating it as a cutting implement or as a ceremonial decoration. We need to know whether we’re thinking of the video game in question as a device for storytelling, a device for social engagement… or as a device for something else entirely. By developing a video game canon that analyzes the contributions of video games to a specific functional role (in our case, to the function of storytelling), we establish coherent standards by which to evaluate video games as succeeding or failing according to that function, regardless of its success or failure at other functions.

A more precise analysis of video games’ storytelling elements. Ever heard the term ‘game feel’? It’s my go-to illustration of the fact that we just don’t yet have a very precise lingua franca for talking about the various elements of video-game storytelling: a lot of what we have, at least in popular discourse, are hand-wavey gestures at feelings that games either elicit or fail to elicit in their players. (Any of my team members would tell you that my skin crawls at the term ‘immersion’, for the same reason.)

This dearth of precision is to be expected: after all, video games are still a very young storytelling medium, and I don’t believe that they’re finished even discovering all of the storytelling elements available to them. But I think that the way to begin making progress towards a more precise understanding of video games’ storytelling elements is to take a serious and sustained look at which video games have excelled in storytelling and exactly how they did it. That serious and sustained look is exactly what the establishment of a canon is all about.

Understanding what video games can do as a medium that other storytelling media can’t. Consider the critically acclaimed Spec Ops: The Line (one of the games I discuss in my rebuttal of Ian Bogost’s claim that “video games are better without stories”).

Spec Ops was lauded for its story—a story that was basically a reimagining of Apocalypse Now’s story (a film), which was a reimagining of Heart of Darkness’s story (a novel). So we can ask: is Spec Ops’ story good because Spec Ops accomplishes something uniquely effective in video-game storytelling, or is its story instead good simply because Spec Ops has tapped into a story that is compelling regardless of the medium in which it’s represented?

I firmly believe that video games can tell kinds of stories that other media can’t. If we want to get a firm understanding of precisely what storytelling features are unique to video games, we need to survey the storytelling of video games as a unique medium—and that’s exactly what the video game canon aims to do.

So there are many benefits to thinking about video-game storytelling in terms of a canon. But, like I said at the outset, there are also drawbacks. In particular, the act of making a canon is inherently exclusionary: it excludes certain video games from the discourse, and it also excludes certain aspects of video games from the discourse.

The canon excludes certain video games by deeming that they don’t belong in the canon. When you think in terms of canons, it’s tempting to write off works that aren’t canonical as not worth your time—and, worse yet, you can end up being biased and only end up considering popular works (or your personal favorites) for admission into the canon in the first place. No canon can avoid this risk entirely, but we can mitigate the risk by consciously trying to consider as many works as possible for admission into the canon in the first place—and by reminding ourselves that works can still be valuable even if their contributes don’t warrant admission into the canon.

The canon excludes certain aspects of video games by only considering video games as a form of storytelling. Remember my discussion of the many functional roles that video games can play? A canon of video-game storytelling can be analytically productive because it focuses on the singular function of video games as a form of storytelling; but this also runs the risk of ignoring the success of video games in other functional roles. The best way to mitigate this risk? Establish canons for the other functions that video games can serve: a canon of video games as educational tools; a canon of video games as a social forum; and so on. (That’s a tall order, but a worthwhile one!)

We need to go into discussions of canon with our eyes open, and with the expectation that we almost certainly won’t end up reaching a consensus on which video games do and don’t belong in the canon. Consensus on a singular canon is not the goal: the goal is to use the perspective that “canon thought” affords to have more productive conversations about the storytelling of video games—conversations that reap all of the above benefits, while avoiding the above risks as much as possible.

ZU: Canons of works already exist for other entertainment mediums, like books. Is the storytelling in video games different enough to make a separate canon necessary? If so, what makes it different?

DAN: When it comes to the question of whether or not storytelling in video games is different enough from literature, cinema, and other forms of media, the short answer is, “Yes, absolutely.” Whereas novels and movies tell a story to a passive observer, video games put the player in the driver seat and tell her that the story doesn’t happen unless she’s progressing forward with it.

This interactivity opens a whole world of possibility when it comes to telling a story and creating a narrative experience for the player in a way that older forms of media simply cannot. And so, just as we would say that the audiovisual medium of cinema deserves to be examined and analyzed as something separate from the imaginative medium of literature, so too do we say that video games have a great deal to offer that no other medium can, and therefore should be examined on their own.

For example, consider The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, which is a perfect retelling of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. Most people are familiar with the hero’s journey thanks to a little film called Star Wars, which George Lucas specifically wrote and directed to be a science-fantasy retelling of Campbell’s heroic formula.

When you sit down to watch Star Wars, you are a spectator watching the story unfold. Ocarina of Time, on the other hand, presents the player with the exact same beats that Star Wars or any other hero’s journey would have, but gives you the chance to control the hero. To become the hero. You’re not just watching Link’s journey across Hyrule, you are taking it, and experiencing what it’s like to be a hero for yourself. For this and many other reasons, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time deserves to be examined through a canonical lens.

This being said, the reasons for a specifically video-game-centric canon are more than just seeing how a new medium can iterate old stories. There are innumerable stories that could only be told via the interactive medium of video games.

Take, for example, a series like Silent Hill, which, on the surface, seems like it could have just as easily been a movie for all its cinematic qualities.

And yet, when you delve deeper into the world of Silent Hill and all its monstrosities, you start to become enveloped by a deep paranoia that what you are seeing isn’t really happening: rather, your experience is being warped by the town itself. The game, by virtue of being about a town that messes with your mind, actually has you questioning your motives as a player. Silent Hill presents true psychological horror because it actually makes you experience it firsthand.

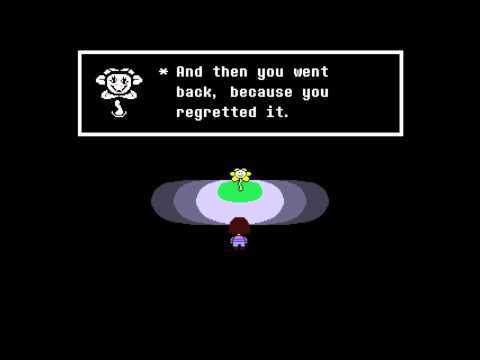

And what of the controversial case of Undertale? Here you have a game that could only exist after decades of other games coming before it. Not only is it a visual throwback to a bygone era of games, but the majority of story and gameplay elements also presume at least a basic knowledge of how video games tend to work, both adhering to and subverting those tropes as the player progresses through the story.

Games like Undertale ask questions of players that most games don’t, and it frames those questions in familiar video-game aesthetics and conventions to make the player question why exactly she even plays games in the first place. And what’s more, from where we’re standing, any story that gathers such vitriolic, hyperbolic attention from the gaming community is worth examining.

So that was the long answer to the question, but, to go back to the short answer: yes, video-game storytelling is vastly different from other forms of media. While it certainly borrows conventions from media that came before it, the interactive medium of video games separates itself by asking the player to take an active part in creating the story. This is the core reason why we should allot games their own canon, and the reason why we do what we do on our website. Video games tell stories that nothing else could.

ZU: What is your process for determining if a game belongs in the canon?

DAN: When I first proposed the idea for Now Loading…The Video Game Canon! to Aaron, we had three main goals that we wanted to accomplish:

- Establish an “In-Between” stage of analysis. The bulk of articles on With a Terrible Fate are steeped in research and analysis, but most of them sprouted from a conversation between two or more analysts on the site about their first impressions of the game. We wanted to show that all of these critical looks at games stem from that initial experience that we all have with a game, refined over and over until we have a nuanced argument to present. Now Loading was an idea we had to bridge the gap between first impression and deep, critical analysis: articles that retained some of that opinionated voice from the initial conversations, but which still had a principled argument to present.

- Create a reference guide to the great video game works. Naturally, one of the goals in making a series about a canon should be to create the canon of works. We thought that it would be prudent to create a reference guide that provides some basic information about a game and what it has to offer. In this way, if someone hasn’t played a particular game and would like a sort of informational primer on it, they could turn to the Now Loading series and get a good idea about the game in question. And, of course, for the series dedicated to making a canon of great works, we wanted to take a good look at certain games so that we can determine whether or not they have reason to be remembered as a great work of art.

- Structure the articles in an engaging way to promote conversation. Perhaps most importantly, we wanted this series to actively encourage community engagement and discussion. Often when people hear the term ‘canon’, they rightfully shy away from it or dismiss it because of how inherently exclusionary it can be. To combat this, we wanted to structure the Now Loading articles in a way that not only could anyone read and enjoy them, but anyone could write one, too. As such, they’re structured in a simple collegiate format, with an introductory paragraph, a few body paragraphs, and, ultimately, a conclusion. So, if someone reads my article on The Legend of Dragoon, say, and doesn’t agree with my points or decision to leave it out of the canon, they can easily write a response piece in the same format that straddles opinion and deep analysis.

The first two of the above goals are accomplished simply by virtue of writing the articles, but the third goal takes a bit more doing. We want the pieces to have a slightly more opinionated edge than other articles on the site, because writing from a certain point of view props the door open for responses from people with opposing or different perspectives.

That’s why I have the articles structured thusly:

Introduction. Here we establish a brief history of the game, and allude to what makes it an interesting candidate for the canon. That “interesting point” can be anything from a well-developed thematic structure in the Silent Hill series to the community-driven development of Shovel Knight.

Story and Characters. This tends to be the bulkiest part of the article, as we at With a Terrible Fate are principally interested in the unique way that video games tell stories. It’s this section that covers the basic plot of the game, as well as the characters and avatar that you play as. It’s also where we typically dive into the nitty-gritty regarding the thematic throughline of the game.

Gameplay, Music, and Visuals. It wouldn’t be much of a video-game analysis without looking at the technical elements that comprise the game, so this section takes a greater look at the way you play the game and how it visually and aurally presents itself to the player. This section can be fairly by-the-numbers, but we often try to focus on elements of gameplay that reinforce the game’s narrative or theme. So for instance, a game like Pokémon Red, which has strong themes of exploration and challenging oneself to be better at every turn, is designed in a way that promotes gathering and putting together better and stronger Pokémon teams so that, eventually, you become the best. Often in games that don’t present an overt story to the player, this section is where visual and interactive storytelling really shine.

Impact on Video Gaming and Culture. Though we tend to judge the game based on its own merits—namely, that of the “text” that is presented by the game itself—we do find it important to see how a game changes video games in general, if at all. This can range anywhere from how a development team changed over time, as with Team Silent, to how a particular game in a long-running series is viewed in the context of the other titles in that series, as with Super Mario Sunshine. This also speaks to an important part of the method we employ in constructing the canon: we look at games that have been part of the culture for a few years so that their impact can be accurately gauged.

BONUS LEVEL. In this section, the author of the article has free rein to talk about whatever she personally feels is worth remembering about the game. It can be anything from just one scene, to a musical leitmotif, to a particular line that a character says that makes the entire game stand out in some small way. BONUS LEVEL is the section of the article that gives the game its proper due, even if the author ultimately decides not to allow it into the canon. It’s the place, for instance, to zoom in on the iconic moment from Silent Hill 3 that makes the player fear she may have been killing people, rather than monsters.

VERDICT. The verdict on whether or not the game is let into the canon is the final piece of the puzzle. It’s the portion of the article in which the author sums up her analyses, critiques, and opinions on the game in question. While the author’s argument is woven throughout all of the article’s sections, this particular section is the “line-in-the-sand” moment that, hopefully, serves to engender some discussion among the readers. Maybe Reader A agrees with every argument that the author made, but has some important reason why the game should get a different verdict than the one the author gave it. Maybe Reader B agrees that the game should be allowed into the canon, but for totally different reasons. The final “yes” or “no” verdict is what not only cements what the author was saying, but also leaves the door open for everyone else to cast their vote, and explain the reasons behind their vote.

Every video game offers a huge scope of possible experiences for the player, and, as such, it would be arrogant to assume that one person’s perspective is the be-all and end-all when it comes to deciding whether or not that game is important. It is our hope that, by presenting these objective criteria and sprinkling our subjective opinions throughout, we lay the groundwork for communal analysis and start discussions about these games that lead to more and better articles. The more we discuss a game, the more we get out of it, and that’s precisely what we’re going for with Now Loading…The Video Game Canon!

ZU: How will you know when the canon is complete? What does it take to truly establish a new canon of works?

DAN: The easy, pithy—and, frankly, classically academic—answer to this question would be to say that, if we ever feel as if we’ve “completed” the video game canon, then we have ultimately failed in what we have set out to do.

Our goal in constructing the video game canon is to establish an index of great video game works that acts as a primer for analytical discussion on the interactive medium. What we are not trying to do is pass down a permanent judgment on every single video game and then etch into stone the perfect list of perfect games.

A canon, as we see it, should be fluid: open to debate and change. Sticking too rigorously to a determined list carries with it a whole host of problems for good video-game analysis, not least of which being the risk of appearing arrogant or elitist. To avoid this sort of elitism that is typically associated with literary, religious, and other cultural canons, we want to keep the canon as open to discussion and revision as possible.

A huge issue we take with other academic canons is their rigidity and unwillingness to accept new arguments or different points of view, and the construction of the video game canon is by no means free of that issue. In fact, for reasons we delve into in other articles on the site, it is actually more difficult to put together this reference guide because video game analysis has to navigate the murky depths of “personal experience.”

Personal experience is an important datum when it comes to analyzing video games and their stories. Games are, after all, an interactive medium, and so the experience that a player has when playing a game is just as important to analyze as the story, gameplay, or visuals. As such, you and I could agree on every single technical aspect of a game, but then have completely different personal experiences with it that color our overall opinion of the game and what it has to offer the medium. We could both be presenting valid, argumentative points for whether it should or should not be recognized by a greater video game canon—even though we disagree with each other, based on our different experiences.

For us to sit atop lofty thrones making concrete decisions on whether or not a certain game deserves to be analyzed or remembered would be to foolishly turn down other people’s opinions and render their arguments completely irrelevant, and we don’t want to do that with this series.

Now Loading…The Video Game Canon! began as a series designed to both create a list of canonical works that we can use as a reference guide for analysis, and to initiate more discussion with our readers. Every canon article is written around a central argument that we hope will elicit a conversation with our readers, because we believe that the construction of a canon must be a communal endeavor. Video games are a medium that we all love and appreciate, after all, so we find that feedback not only exciting, but also intellectually stimulating.

By listening to feedback and starting the conversation, we are able to—as analysts, readers, and people who enjoy video games—gain a broader perspective on video games that we may have otherwise categorized and shelved away, never to be thought of again. This is obviously a mission statement we have for our specific series, but we also wholeheartedly believe it should be how any canon should be approached. As we see it, the more arguments we have, the better, because they can only lead to a deeper understanding and greater appreciation of the work being discussed.

So, we hope that the canon is never truly finished, because that would also mean the end of the discussion.

ZU: The canon of works is not the only topic that With a Terrible Fate covers. One of your articles suggests that the Switch has the potential to revolutionize the players’ relationship with characters and avatars in video games. Can you elaborate on that?

AARON: The seeds for that article about the Switch came from my original work on Majora’s Mask. While I was waiting for Majora’s Mask 3D to come out, I wrote an article speculating about how Majora Mask’s story might change by being represented on the portable console of the 3DS. (When I analyzed Majora’s Mask 3D after its release, I concluded that the change in console does indeed change the story in thematically foundational ways.)

This work planted an idea in my head: maybe the features and limitations of specific consoles influence the kinds of stories that it’s possible to tell about them. When I say this, I’m not talking about the ability of the Xbox One to tell stories with better graphical definition than the NES: I’m talking about the ability for different systems to influence the very relationship in which you, the player, stand to the worlds of your favorite video games.

When I got my hands on a Switch, I didn’t just get excited because it felt amazing to game on it: I got much more excited because I saw the potential it has to tell new kinds of stories that other storytelling media, and even other video-game consoles, can’t.

My central idea about the Switch is this: the console’s dynamism—that is, its ability to change from being stationary to being handheld, and from using button inputs to using motion controls—empowers it to tell new stories that feature similarly dynamic relationships between the player and the game. More specifically, the Switch has the ability to establish new relationships between:

- The player and the avatar

- The player and the game’s world

- The player and other players of the same game

I go through the theory that underlies these claims at great length in the article itself, so for the purposes of this interview, I just want to highlight the examples I give of hypothetical stories that centrally depend on the kinds of dynamic relationships that the Switch makes possible.

A game with a dynamic relationship between player and avatar: “The player encounters a mechanized avatar—it’s a robot, or automaton, or whatever your preferred term for a remote-controlled humanoid is. The player, within the fiction of the game, is explicitly given the task of controlling this robot in order to go on a quest and save the world.

“Now, the player can use all of the ordinary, symbolic controls (A/B/X/Y buttons, control stick, etc.) to manipulate the robot; or, they can use the Switch’s motion controls to ‘embody’ the robot and allow it to commit much more nuanced and powerful actions—maybe, for instance, there are some doors or enemies that can only be surmounted when the player uses special motion commands.

“However, there’s a catch: using motion controls is so powerful because (within the context of the fiction) the motion controls bind the player’s soul to the robot; as a result, if the player uses motion controls too much, the robot will actually develop a soul of its own, thereby gaining free will, and the game will end in failure because the player will no longer be able to control the robot.”

A game with a dynamic relationship between player and game world: “Imagine a game in which the avatar has some kind of quest to complete in their ‘real world’ (i.e. the avatar’s real world, not the player’s). However, the avatar also has a unique ability: at night, he can use his dreams to access a parallel dream world to allow him to advance in his quest in altogether different ways.

“This dream world, unlike the avatar’s real world, is directly linked to the player’s real world: using location-based data (maybe collected from Wi-Fi networks, or whatever), the game generates dream-world locations that correspond to nearby locations in the player’s world. Maybe these correspondence relations are somewhat direct—maybe, for example, real libraries in the player’s world serve as dream-world libraries that provide new, uniquely useful information on the game’s world and characters. Or maybe the correspondence relations are more symbolic: maybe major landmarks in the player’s world correspond to something like procedurally generated dream dungeons in which the avatar can acquire unique abilities, equipment, and the like.”

A game with a dynamic relationship between player and other players: “Imagine a game that’s like Dark Souls in the following sense: it has a world and quest that’s perfectly well-suited for a single player and avatar to traverse, playing through a story from beginning to end; yet it also has multiplayer functionality, supported by a narrative explanation of that functionality: there’s some kind of item in the game’s world that allows avatars to summon other avatars (and, consequently, other players) from other ‘dimensions’, or planes of existence, or whatever spatiotemporally distinct form of existence you prefer.

“This game spells out the fictional mechanics of this summoning process in more detail than Dark Souls does: in particular, it’s part of the game’s fictional universe that these avatars are controlled by ‘spirits’, powerful extra-dimensional gods who have taken a special interest in these avatars for one reason or another. ‘Summoning’ taps into the fabric of the game’s universe and causes these gods to resonate with each other, and—crucially—the closer the gods are to one another, the stronger this resonance is.

“In practice, that means that when real-life players are literally closer to one another, their avatars can summon each other and get all kinds of additional abilities that they couldn’t get otherwise: maybe players’ being within a certain radius of each other would allow their avatars, upon teaming up, to access supremely powerful magic, or to access the special abilities of other classes (e.g., a knight could use the others of a mage), or other kinds of powers altogether.”

One of the reasons why I love Nintendo is that, beyond producing great series like Zelda, they’re constantly innovating new ways for us to play video games. I can’t imagine a new version of the PlayStation or Xbox like opened the door to new kinds of storytelling in such a radical way as the Switch has done. I haven’t yet seen this focus on the storytelling capabilities of different consoles penetrate mainstream video-game discussions very much, but I’m hopeful that this will change soon, especially given the advent of the Switch.

This article on the Switch also points to one of the tenets of With a Terrible Fate that guides every piece of our content: in order to fully understand and appreciate the storytelling of video games, you need to analyze video games holistically. A video game’s story is not identical with its plot: everything from music, to user interface, to hardware is a part of the cohesive story that a gamer experiences when she plays through a game.

An approach to video-game analysis that takes all of these factors as story-relevant data is what With a Terrible Fate calls object holism, and you can learn more about it in the footage of our PAX West presentation and my article on a three-stage method to analyze the stories of video games. It’s our ardent hope that this methodology will continue to gain traction as a way to correct some of the shortcomings in current popular discourse about video games.

ZU: Some Zelda Universe team members were in attendance at your panel at PAX South earlier this year, and you are scheduled to present again at PAX East on April 5th and 6th. What can attendees expect to hear at your next panel?

AARON: We’re honored and thrilled to be able to announce that we’ll be offering three panels at PAX East this April. On Thursday, we’ll be presenting “Can Fan Fiction Teach Us About the Official Zelda Timeline?” and “Which Games Belong in the Video Game Canon?” On Friday, we’ll be presenting “Sequels, Series, DLC: How Games are Changing Storytelling.”

Our first Thursday panel is all about With a Terrible Fate’s ongoing series, Hero of Time Project. Two of our analysts, Jaron and CJ, are working on writing a new kind of analytic fan fiction: a fan-written video-game story intended not only to fill the gap between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, but also to provide an entirely new way of understanding the Zelda series itself. Aaron will kick things off by discussing the common conception of fan fiction and what makes analytic fan fiction a different kind of storytelling; then, Jaron and CJ will dive into what motivated them to take on this project and how you can start making your own analytic fan fiction! Zelda fans shouldn’t miss out on this.

Our second Thursday panel will focus on our ongoing series, Now Loading… The Video Game Canon! It will be a version of the panel we gave at PAX South, and we’ll cover a lot of the canon-centric issues that we’ve discussed in this interview. What we’re really excited about is that we’ll be spending the second half of this panel working with the audience to actually decide whether or not a particular game belongs in the canon. We did this at PAX South with Portal, and we’re excited to continue the conversation in Boston.

Here’s how that’ll work. We’re going to have five members of our team—Aaron, Dan, Richard, Skylar, and Matt—on tap, with a list of ten games that we’d love to discuss with PAX attendees. We’ll have attendees vote, live, for which game they’d like to discuss. Then, we’ll take the top-voted game and debate with the audience whether or not it belongs in the video game canon. We did this at PAX South with Portal, and we’re excited to continue the conversation in Boston. The project of building a canon is at its best when we get the whole community involved in the deliberation process.

On our Friday panel, four members of our team—Aaron, Laila, Jaron, and CJ—will explore the ways in which video games are innovating new, rich methods of serial storytelling. Increasingly, video games are telling their stories episodically—where this might include anything from story-rich DLC, to series with a ton of flagship titles (looking at YOU, Zelda), to games that are released in bite-sized installments (e.g., Telltale’s games, or mobile games like Brave Exvius). We want to explore which of those episodic tactics are changing the landscape of storytelling, and how they’re doing it.

We don’t want to give too much away about this one, but here’s something in between a teaser and a synopsis. The presentation will be in three parts.

- Aaron will be examining Dark Souls III’s DLC in order to answer the question: are there any stories that must be told as DLC, rather than as part of a full video-game story?

- Jaron and CJ will dive headfirst into the Zelda series and try to convince you that you should care way less about the games’ timeline than you probably do.

- Laila will draw on her recent work on Okami to show you that many games you think of as standalone titles are actually part of a long-running series: a series of retold and reimagined myths.

We’re fortunate that this will be the fifth PAX at which we’re presenting our work, and we love the convention: every time we go, we meet so many compassionate, interesting, and sharp-minded gamers. We can’t wait to keep this tradition going at PAX East 2018, and we hope to see some of you there!