The immersive virtual worlds of video games can generate an unrivaled level of investment and engagement on behalf of the player. Given that this is the case, allowing a player to create an avatar, customizing features like background and skills, should only serve to increase the level of investment possible. Paradoxically, though, this exact kind of customizability can hugely hinder player immersion if it’s executed poorly.

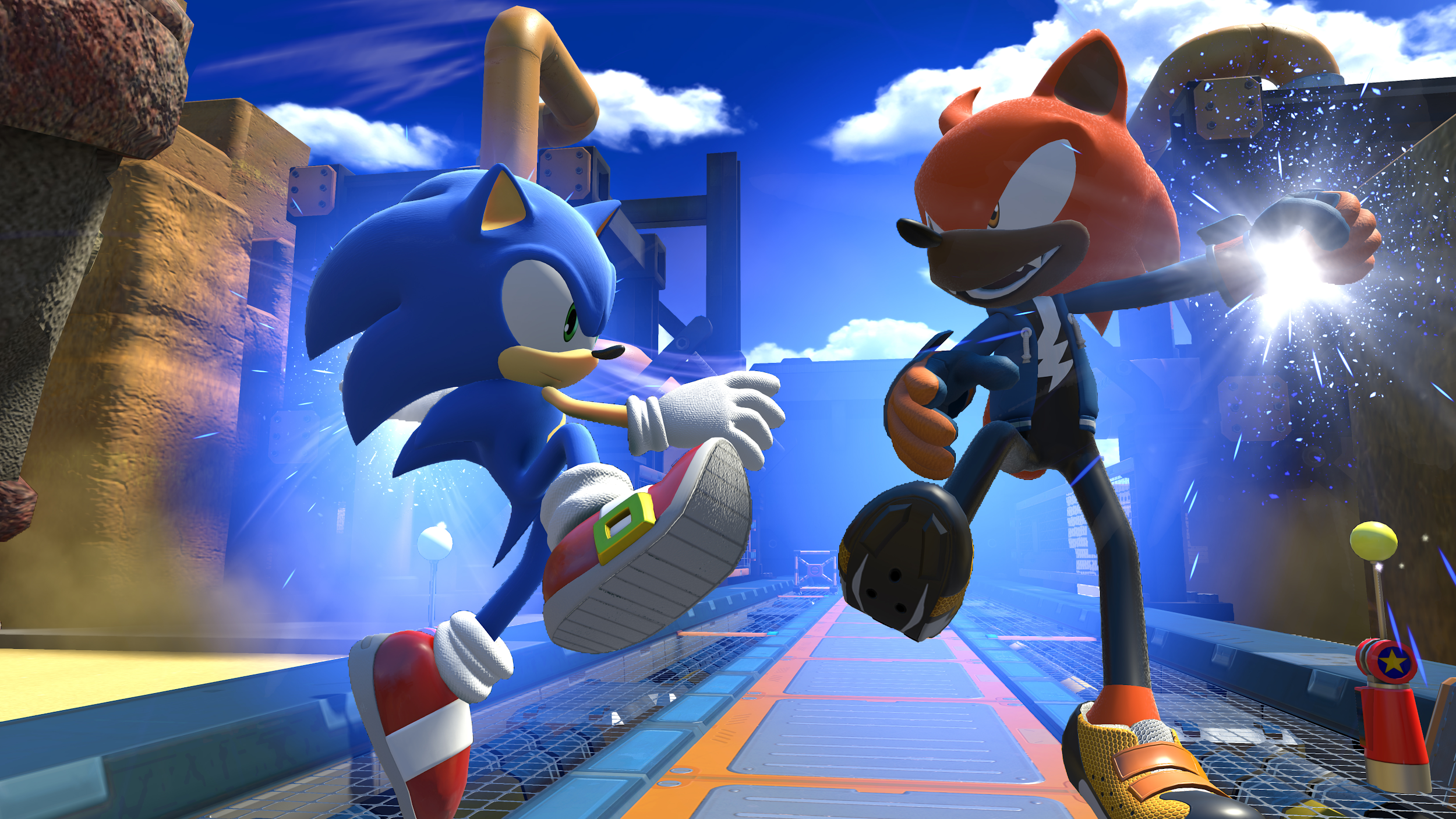

Such is the case of the player-created avatar in Sonic Forces, Sonic the Hedgehog’s most recent video game, a bleak scenario in which series antagonist Eggman has conquered over 99 percent of the globe.

I am hardly the first person to point out that Sonic Forces displays an abundant number of storytelling gaffes. As Andrew Stretch of TechRaptor.net says:

“Sadly, it’s nearly impossible to tell what this world of Eggman’s looks like because we get to see none of it. Aside from cutscenes at the resistance headquarters or stage backgrounds, practically nothing is known of the world before or after Eggman takes over. With no knowledge of the damage, there are no stakes to bring depth to the simple plot.”

Sonic Forces fails to capitalize on the storytelling opportunities of its strikingly grim premise. Most of these failures are simply underwhelming implementations of interesting ideas, and Sonic Forces’ avatar is no exception. The implementation of the avatar, however, goes beyond simply disappointing: the avatar represents a failed implementation of player-created protagonists, at least as far as storytelling goes. By looking to the opposite of what Forces does, we can begin to construct a picture of how player-created protagonists can and do make many video game worlds more compelling.

In so doing, we arrive at the main idea I intend to explore: although player-created avatars can make players feel more invested in stories, poorly executed integration of avatars can actually have the opposite effect. I believe this idea is best explored in three steps. First, I consider the storytelling challenges and idiosyncrasies that are inherent to player-created avatars. Secondly, I examine Sonic Forces to reveal why exactly it fails so badly in attempting to surmount these challenges. Finally, I propose ways that Sonic Forces could have better implemented its avatar, and what this implies for story-driven avatar creation more generally.

Backstory: Crucial Element of All Protagonists, Customizable or Not

The degree to which a player is able to customize avatars varies from game to game. From a storytelling perspective, I believe the most meaningful customization is the ability to create a backstory for an avatar.

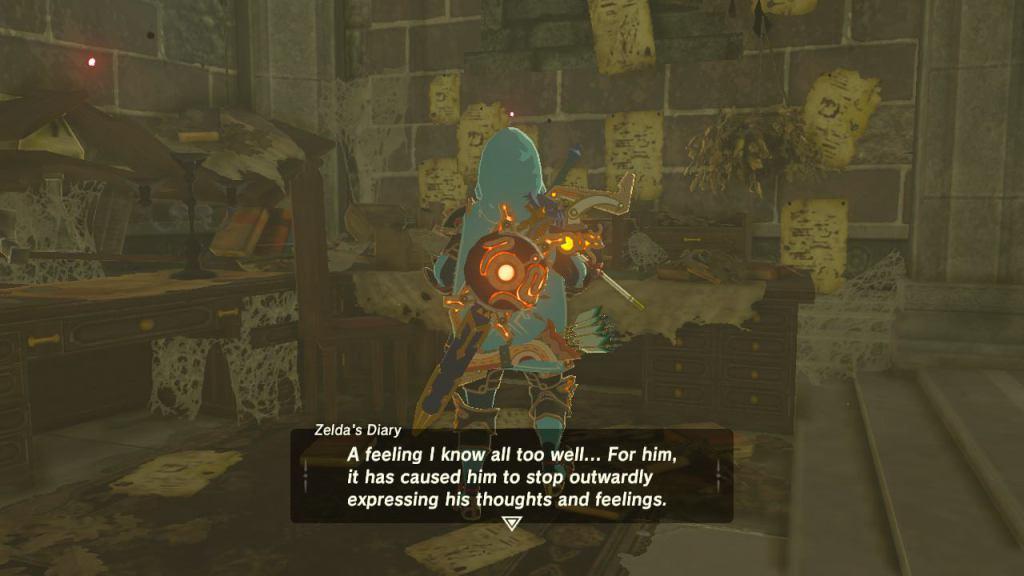

It should come as no surprise that storytelling is greatly facilitated by knowing the histories of the characters involved. A pre-established backstory enables striking forms of storytelling that are not otherwise possible. For example, the backstory of Link in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is pivotal to the game’s world, even if this backstory isn’t known to the player at first.

Without such an intricate and emotionally complex backstory for Link, Breath of the Wild’s overarching themes of history and ancestry would not be as well-integrated with the central narrative. Such themes of history need not be dramatic and grandiose; even in something like Super Mario Odyssey, knowing Mario’s past exploits in Donkey Kong enhances the significance of Mario visiting New Donk City and its mayor, Pauline.

The story arc of Sonic Forces’ avatar never aspires to explore these themes, so a comparison with Breath of the Wild or even Odyssey may seem unfair. My point is that Sonic Forces’ avatar could not invoke these themes in the same manner as Breath of the Wild, even Forces aspired to do so. By the time the player assumes control of Link at the Shrine of Resurrection, the story of Link and Hyrule has mostly unfolded beforehand, completely independent from the player’s intervention. This setup is not possible if the player has to clarify an avatar’s background—or at least, the story would need to accommodate many possible backstories, losing the core focus on Link seen in Breath of the Wild.

Backstory does not need to explicitly be spelled out to the player through flashbacks and the like. Many compelling avatars reflect their backstory through gameplay, without any time set aside for explicitly narrating the character’s backstory.

A stellar example of this kind of storytelling through gameplay takes place at the start of Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, when we find hero Nathan Drake dangling from a destroyed train on a Nepalese mountain cliff, without a shred of context. Although Drake is clearly exhausted, he is unphased by his situation, his movement up the cliff slow but sure-footed. In this introductory sequence, we are given a picture of Drake as a man made resourceful and world-weary by his range of experiences, yet still someone vulnerable enough to end up in peril.

Given Drake’s frequent wisecracking later in the game, seeing him in a calmer and more contemplative state makes him more relatable to the player. Since all of this is presented as a tutorial sequence, the player need not even be aware of the storytelling taking place. No backstory is stated, but its presence is still palpable.

I have turned to other games to provide context for discussion, but this article first and foremost concerns Sonic Forces. Let us recenter our focus on Forces.

Force Farce: The Flaws of Sonic Forces’ Character Customization

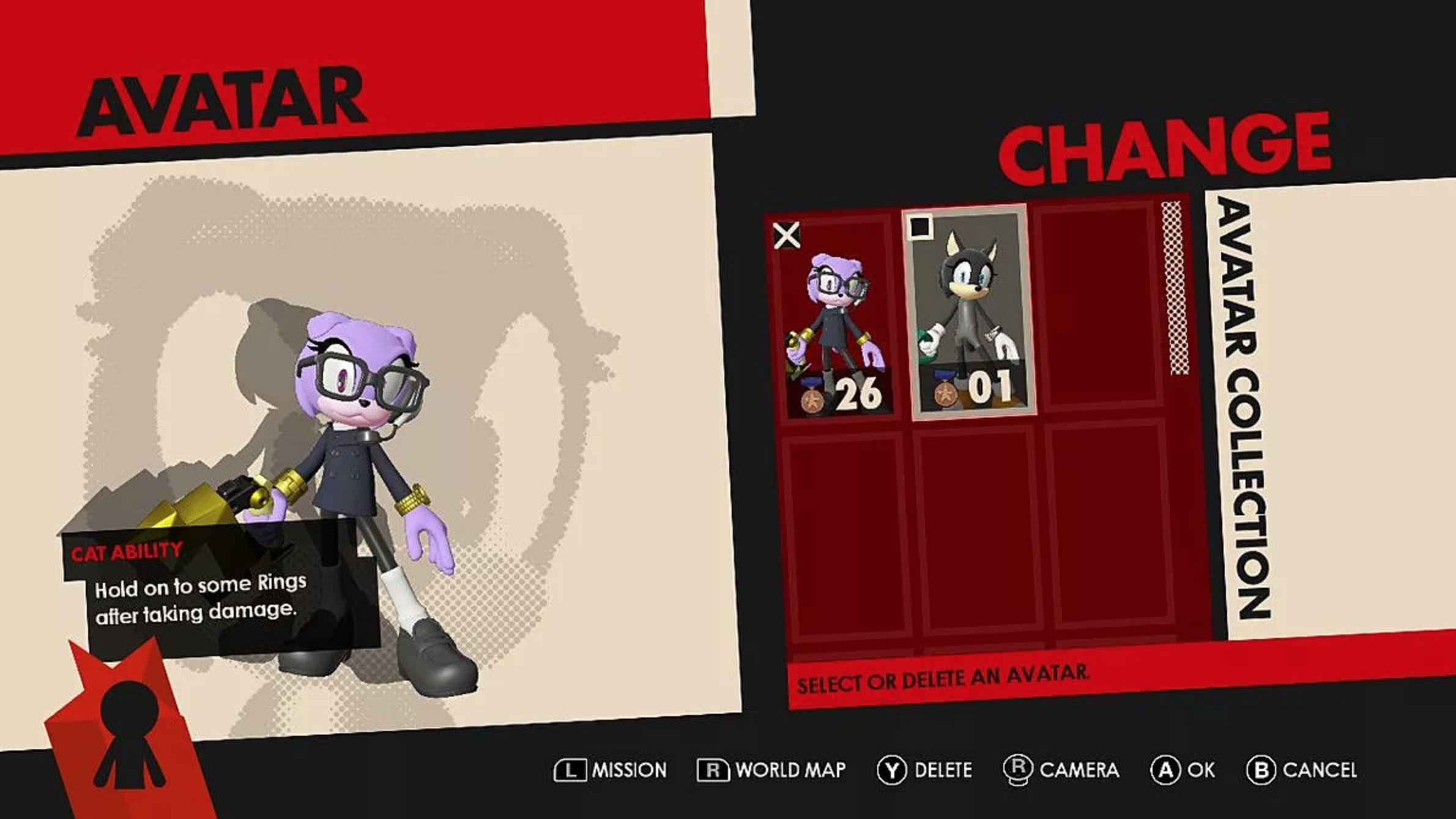

The developers of Sonic Team have repeatedly stated that they had one major intention when introducing the avatar into Sonic Forces. According to franchise showrunner Takashi Iizuka, speaking to Nintendoeverything.com:

“When we were thinking about the concept of Sonic Forces, we received a lot of fan letters and messages from fans where they wanted to create their own characters. So we listened to that and wanted to make their dreams come true. So that’s one of the reasons why we created the custom character system.”

This motivation helps to explain the complete lack of backstory (or backstory customization) granted to Sonic Forces’ avatar. There is no way that the game could account for the multiplicity of backstories, personalities, and aspirations that fans have given their original characters over the years.

Rather than finding a creative way to address this limitation, though, Sonic Forces simply bypasses backstory altogether.

The avatar’s backstory is minimal: their friends were killed by the villainous Infinite, and the avatar eventually volunteers for Sonic’s resistance army to move past this traumatic event. The avatar never speaks, which prevents the avatar from violating the player’s intended personality for the avatar.

Yet, silent protagonists in video games can remain silent while still having something interesting to say, paradoxical as that might seem. Zelda’s diary in Breath of the Wild reveals that the always-nonverbal Link can in fact speak, but chooses not to do so in order to avoid violating others’ expectations of him. As Zelda’s personal diary attests, “With so much at stake, and so many eyes upon him, [Link] feels it necessary to stay strong and to silently bear any burden […] Everyone has struggles that go unseen by the world.”

This statement applies just as well to the avatar of Sonic Forces as it does to Link, and yet nothing is made of the avatar’s silence. By the end of Sonic Forces, Sonic and the avatar are (literally) fast friends, but the avatar has never spoken a word to Sonic. Establishing what Sonic sees in the avatar is left as an exercise for the viewer’s imagination.

Even the one attribute unambiguously associated with Forces’ avatar, bravery, is told to the player again and again, rather than being shown to them naturally. Let me explain why I find this dissatisfying as a storytelling technique.

The avatar’s involvement on missions is treated as an act of extreme courage by the leaders of Sonic’s Resistance. Despite this, many other Resistance members are understood to be taking equally dangerous missions in parallel with the avatar’s—the player just doesn’t see these missions. When other members of the Sonic cast risk life and limb, this is nothing more than routine; yet, for doing the same thing, the avatar is called courageous.

Objectively speaking, then, everyone should be labeled as brave, and the avatar receiving a disproportionate amount of praise doesn’t ring true in the context of Sonic Forces’ story. Even at game’s end, when the avatar leaves the now-obsolete Resistance, the player has little reason to wish the avatar well in the future, since there is no indication of how the avatar will spend his or her time in the future.

The time has come to consider Sonic Forces as it might have been, rather than Sonic Forces as it turned out in real life. Levying criticism against the game is only constructive insofar as it points to a way forward. By bringing together everything discussed thus far, with an emphasis on backstory, I believe I can begin to envision a better way forward for Sonic Forces and its avatar.

How to Improve Sonic Forces, and Lessons for Future Games

As we saw in the case of Breath of the Wild, fixed backstories allow developers to populate game worlds with nuance and meaning specific to that backstory. When character-creation mechanics are introduced for an avatar, that avatar’s backstory cannot be fully known before the player launches the game. Sonic Forces does nothing to push against this limitation, providing only minimal framing for the events taking place.

So, how can future games do better? How can an avatar explore their history meaningfully, either explicitly or through gameplay?

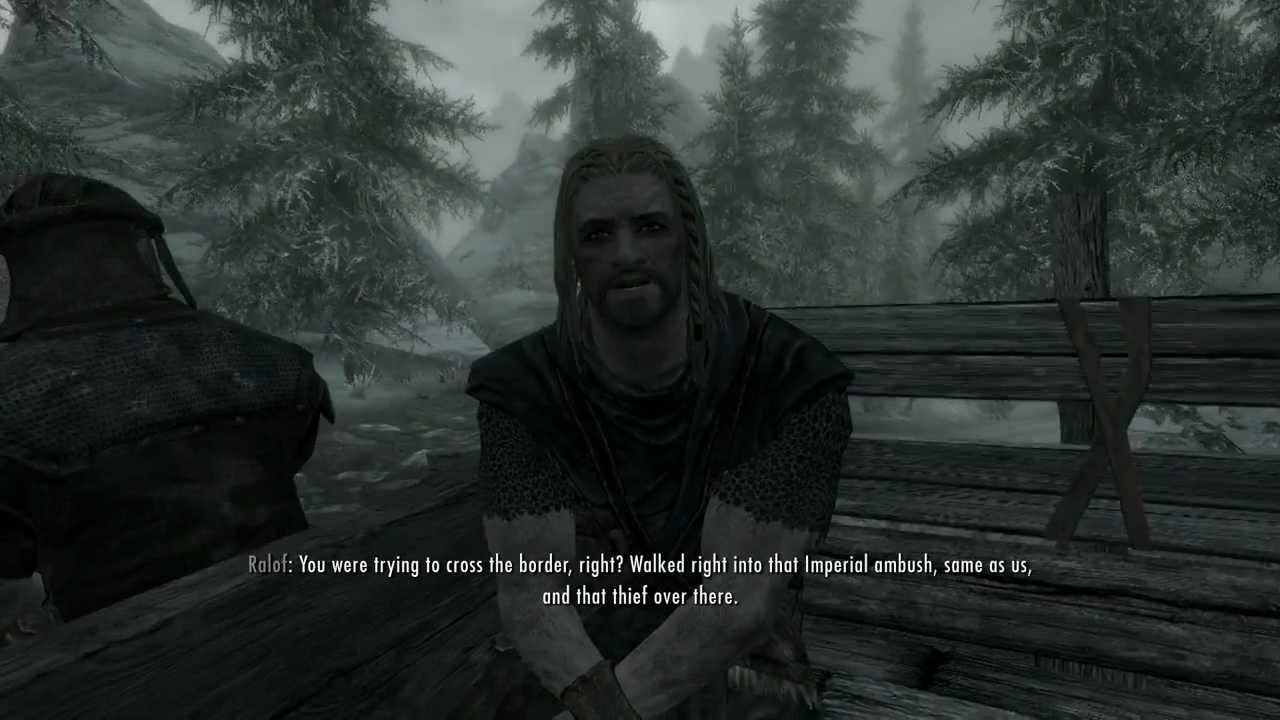

Defining an avatar’s experiences following the start of the game—which is to say, the events of their quest-—is the most straightforward task, but a crucial one regardless. The avatar must be able to make choices of some kind, such that two avatars can make two entirely different sets of choices. This is fundamental to the lives of the avatars at the heart of Skyrim and similar games. The importance of this design is that no two custom avatars can be swapped for each other, without thereby changing the story.

In Sonic Forces, when the game is completed for the first time, the player gains the ability to swap out avatar designs at will. There is no justification for this in-universe (e.g., plastic surgery, à la Fallout 4). No matter what your character wears, does, or is, absolutely nothing changes in the world of Sonic Forces. In this instance at least, being able to swap out avatar designs strips any particular avatar design of its uniqueness and importance to the story.

Accounting for the avatar’s experiences prior to the start of the game is more difficult: how can a game world play off the nuances of the hero’s backstory when said backstory cannot be solidified beforehand?

A basic solution would involve side quests becoming available only if the avatar has a backstory with specific elements chosen by the player. I remember being disappointed during Skyrim’s Dawnguard DLC, when the Dragonborn is asked about the relationship between themselves and their parents. I hoped this might result in the Dragonborn being able to engage with their past in various ways, but the topic was quickly jettisoned indefinitely. Likewise, the only xenophobic remarks directed at my Dragonborn, an orc, came from generic guards: despite the Stormcloaks’ ethnic purity being a major motivation for the civil war, the Stormcloaks never once remarked on my avatar’s body or background.

So, what could Sonic Forces change within its story to better differentiate between avatars?

This could be something as simple as offering a choice of a “safe” or a “risky” path through a level: the avatar’s choice of route reflects on their personality, albeit in a very basic fashion. In regard to in-game dialogue, the avatar should at least have the ability to express one of several personalities, standard in many modern games with avatars.

In regard to the avatar’s backstory, the player might be asked to specify one of several backgrounds for the character, resulting in minor gameplay and dialogue differences. For example, if Sonic Forces’ avatar were established as a street urchin prior to Eggman’s cataclysmic takeover, perhaps the avatar could take hidden shortcuts in specific city levels, based on their experience navigating the city. Additionally, just one or two lines of contextual dialogue from bystanders (e.g., “You lived here, right? I imagine this must be difficult to fathom…”) would go a long way towards making one avatar different from any other.

Although Sonic Forces is in more dire need of improved storytelling techniques compared to many other games with customizable avatars, all games should aspire to improve their storytelling where they can. I will therefore conclude by exploring the larger takeaways that are broadly applicable to video-game storytelling, beyond just Sonic Forces.

One-Character Limit: Looking to the Future

Few things enhance the gaming experience more than feeling an intense connection to the world on the screen. This feeling of immersion can arise from a world that exists independently of the player’s interaction (as with Breath of the Wild), filled with a history and secrets for the player to uncover. But this feeling can also emerge from the act of creating a game’s protagonist: by being personally responsible for something in the game world, the game is no longer a pre-existing object for the player to explore; it is now irrevocably the player’s own.

Or, at least, it should be the player’s own. The worlds of games like Skyrim are heavily impacted by the kinds of actions the avatar takes, so one cannot simply borrow a friend’s save file and expect the world to remain unchanged. Sonic Forces allows for any possible avatar to be completely interchangeable with any other, such that the player’s choices for the avatar make no difference in the game world. This upholds the developers’ goal of letting fans import their pre-existing characters, but it essentially presupposes the player has already crafted an elaborate fan fiction for the avatar. For players who do not have such self-produced, ancillary materials at the ready, Sonic Forces’ avatar is inexplicable in the overall logic of the story.

This need not be the case, to be sure. Even a few small steps to distinguish one avatar from another would be helpful in terms of advancing the storytelling. Sonic Forces ultimately ends on an optimistic note, with the heroes facing the arduous task of rebuilding a liberated world—and, in some sense, I see this ending as being analogous to the perils of customizable avatars in storytelling. No matter what history might burden the technique of customizable avatars, nothing about avatar customization is inherently opposed to good storytelling in games. With diligence, game developers can learn from errors of the past to create a brighter future for interactive storytelling. But that redemption will take much introspection about the roles that avatars can and should play.

1 Comment

LoSzeged · September 16, 2018 at 10:30 pm

Totally agree with you on these points mate. Ya pulled at my dreams when you started talking about differentiating character backgrounds and having the odd sidemark of ‘you used to live here..’ and the vivid world depictions I could see.

Hurts that the Sonic games probably won’t ever be as good as we can imagine..

nice article.