Critical Review is a series in which With a Terrible Fate’s video game analysts critically evaluate the work of themselves and other analysts, with the goal of advancing our collective understanding of video-game storytelling.

How do you give a gamer control of an all-powerful god and still keep the game’s story interesting?

There’s a reason why so many games tell the story of a hero overcoming a god, and not the other way around. In games like Final Fantasy VII, Xenoblade Chronicles, and The Legend of Zelda, the player has to face the nearly impossible task of overcoming an enemy who has total authority over the universe and is therefore always five steps ahead of them.

When you’re up against a timeless usurper who shrouded the world in twilight and survived his own execution, there’ll be no shortage of dramatic tension in the story.

It’s much harder to build up any sense of dramatic tension when the player is in the driving seat of the omnipotent deity: if the god really is omnipotent, it’s hard to imagine how any foe could be a substantial enough threat to keep a video game’s story going for even a few hours, let alone sixty or eighty.

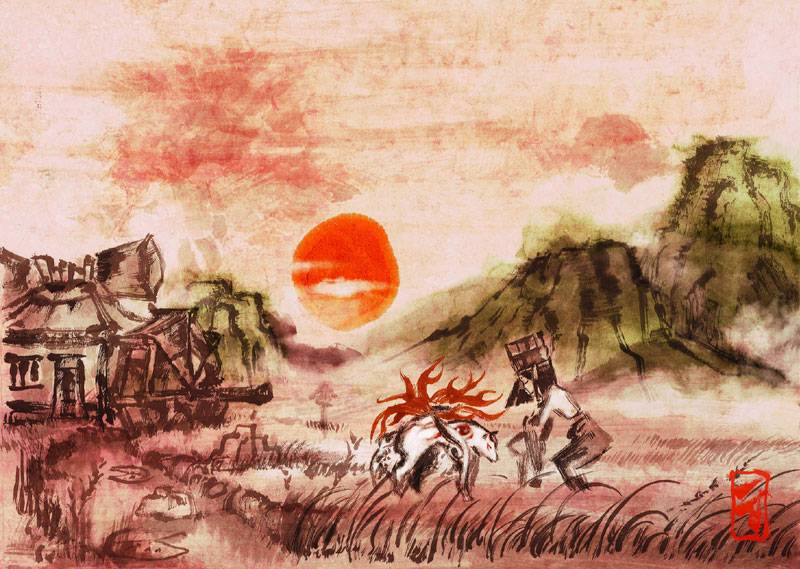

But that’s exactly what Okami succeeded in doing. It put players in the role of not merely a goddess, but also one of the most important goddesses in the Shinto tradition, Amaterasu. Laila Carter illustrated the gravity of this avatar’s identity in her most recent article about Okami, “How Okami Transformed the Meaning of Characters like Amaterasu”:

The player is the “best” goddess in the Japanese pantheon, and, despite all the other gods, the game designers deliberately made it so that Amaterasu specifically is the main avatar. Amaterasu re-draws the world with her calligraphy, Amaterasu restores the celestial brush gods, and Amaterasu drives away the evil and restores order. The brush gods refer to her as “Origin and mother to us all,” referencing how she is the mother-goddess and goddess of the entire cosmos.

Amaterasu is to goodness as Ganondorf is to evil: an absolute, boundless manifestation.

How does Okami manage to tell a rich and engaging story despite the divine authority of Amaterasu? I want to draw on Laila’s analysis to argue that it achieves this by telling a story that is actually about the player’s agency over the game’s world and events, rather than about good triumphing over evil.

To begin, I’ll show that the game involves the player herself in its story—not simply by giving them control of a divine wolf, but rather by allowing them to play the role of a goddess who is manifesting herself as a wolf. Then, I’ll draw on Laila’s analysis of the relationship between Okami and the Kojiki, a seminal Shinto text in Japan, to argue that Okami’s story is centrally concerned with the player imposing her will on the world of Nippon, rather than just “saving the world” from evil. Ultimately, we’ll see that Okami is a compelling example of a principle of storytelling that, while obvious, bears repeating in the modern landscape of storytelling: you don’t need the threat of a hero failing to keep your audience interested in your story.

A God, a Player, and an Avatar Walk into a Game

The player isn’t idly controlling an avatar in Okami: she’s playing the role of a goddess who’s manifested herself as an avatar. It might not be obvious why this difference matters, but it ends up involving the player in Okami’s story far more than the average video-game story involves its player.

In her article, Laila remarks that the avatar of Okami—the divine wolf whom the player controls—is an example of what she calls a blank avatar: such avatars “usually do not speak at all, and the player has great control over their responses to situations.” The avatar’s “blankness” allows the player “to believe that they can interact and shape the landscape of mythopoeic Japan through their own power; through the Amaterasu avatar, the player is able to stop the evil Orochi and transform Japan into a beautiful place.”

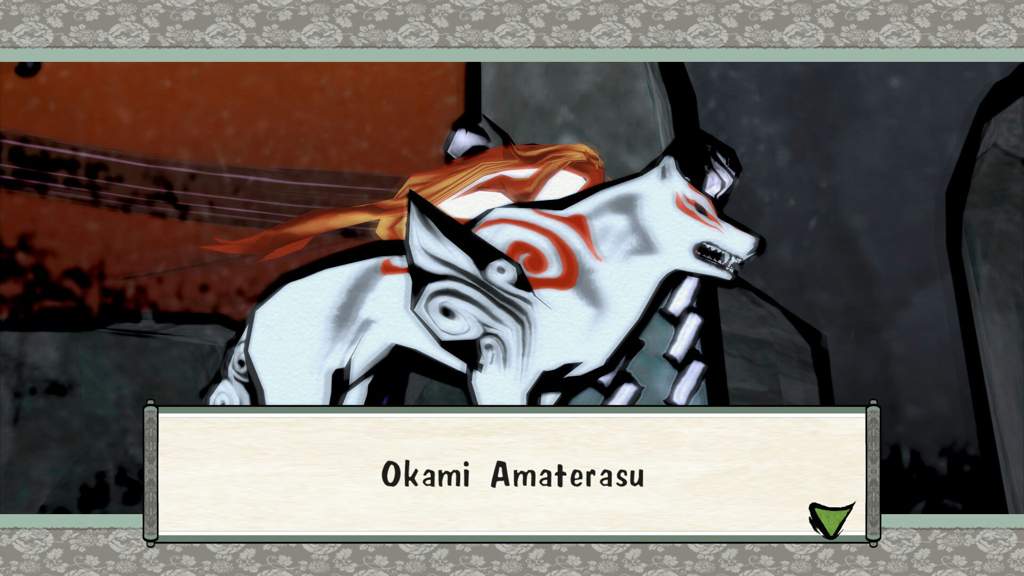

The avatar of Amaterasu—and the player—in Okami.

I agree with Laila that the nature of Okami’s wolven avatar empowers the player to impress her will on the game’s world of Nippon, but I want to suggest that Okami empowers the player in ways that other games with blank avatars don’t. The key to this is to recognize that the player’s wolven avatar in Okami is not Amaterasu: the wolven avatar is, in fact, the avatar of Amaterasu.

That last sentence is confusing because it, like Okami, trades on two distinct usages of the term ‘avatar’. Since thousands of years before video games were invented, the term ‘avatar’ has had a similar meaning in theology: the avatar of a god was the physical manifestation of a god in the world of mortals. Gods are understood in many traditions to be eternal and infinite: they aren’t bounded by time or space like the physical world is. So, when gods have reason to intervene in the affairs of the physical world, they do so using avatars: physical forms that exist within the constraints of the physical world and that act as agents of their god’s will.

In Hinduism, Vishnu is the standard example of a god with many avatars: according to Hindu tradition, he would use these avatars to empower goodness in the world and fight evil. (Source.)

Strictly speaking, the white wolf of Okami is not Amaterasu: the white wolf is Amaterasu’s avatar, the physical form she has created to banish darkness from Nippon.

The consequence of this is that, within the story of Okami, the player isn’t supposed to imagine herself as playing the role of a wolf: rather, she’s supposed to imagine herself as Amaterasu, the goddess who exists outside of Nippon’s physical bounds, engaging with Nippon by manipulating an avatar that exists within Nippon.

The literal player of Okami, just like the goddess Amaterasu in its story, exists outside of the game’s world, manipulating it through the in-world proxy of a wolven avatar. This might not seem significant, but it ends up involving the player in Okami’s story in a compelling and unusual way. We can see this by contrasting Okami with a strikingly similar one: The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess.

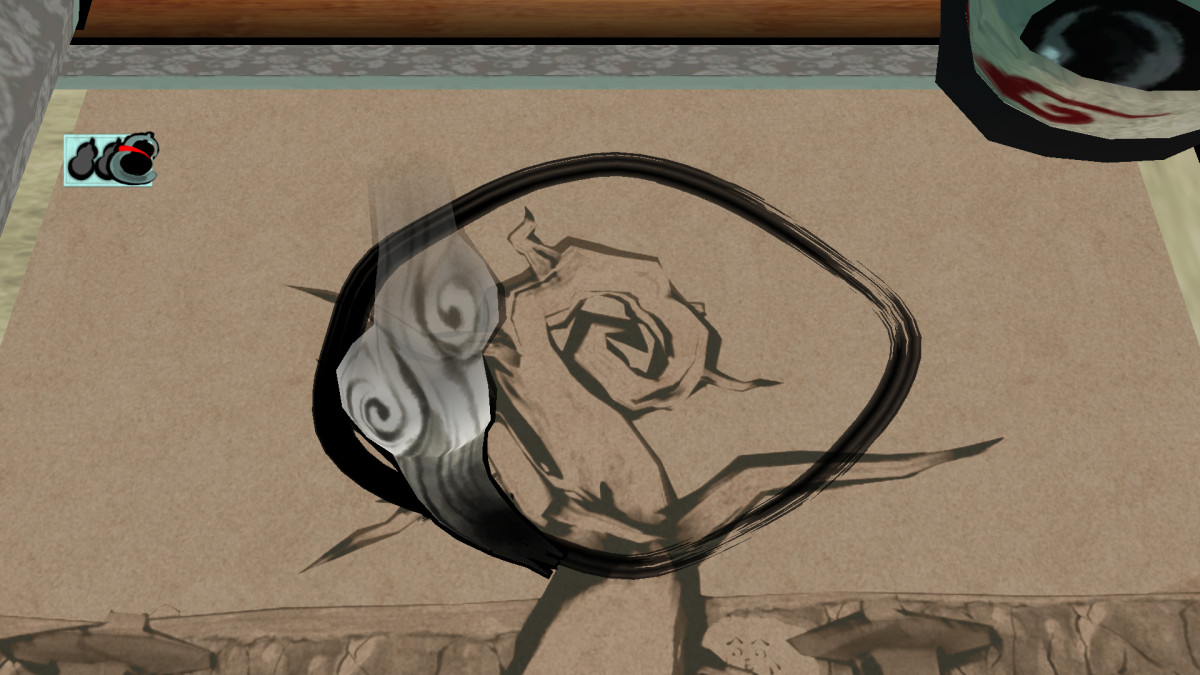

Okami provides its player with all the accouterments of the “origin and mother to us all.” You don’t just control a wolf: you also have control of the Celestial Brush, a divine calligraphy brush that allows you to bring about physical changes in Nippon merely by drawing on an image of the world—an especially visceral experience in the Wii version of the game, which uses the Wiimote and its motion controls as a way for the player to imitate the process of calligraphy.

Draw a circle around a withered tree with the Celestial Brush, and watch it bloom.

If you go into Okami supposing that the player is actually meant to imagine herself as the white wolf in the game, it’s hard to make sense of the Celestial Brush—are we meant to imagine that the very same white wolf that appears on our screen as we freeze time and begin painting has somehow taken up a brush and begun to paint on the world?

On the other hand, if we analyze the player as playing the role of Amaterasu, her control over the white wolf and her control over the Celetial Brush dovetail into a natural and satisfying understanding of the player’s place in the story: she is acting on the world as a boundless god, and a boundless god is plausibly able to both:

- influence the physical world internally by creating and controlling a physical manifestation (i.e. an avatar) within that world

- influence the world externally by using her abilities (i.e. the Celestial Brush) to fundamentally alter the physical composition of that world

The character of Amaterasu—the goddess, not the wolf—provides a natural role for the player to occupy in the story: the character’s status as a divine being acting on the world of Nippon from outside of it mirrors the status of the literal player of the video game, making it easy for them to empathize with Amaterasu and thereby to become invested in her mission to purge Nippon of darkness.

The value of this kind of empathy between player and character becomes evident when you consider a game that lacks it—like Twilight Princess (a game that I love, by the way—so don’t take the following criticism as a denial of the game’s value). Twilight Princess also features a wolven protagonist: Link, our human (well, “Hylian”) avatar, is transformed early on into a wolf; and, as the game progresses, the player is able to shift between Link’s human and wolf forms.

A Tail of Two Wolves. (Game analysis: now with puns!)

It’s easy enough for the player to imagine herself as a humanoid avatar—someone with a familiar psychology, anatomy, and perspective on the world—but it’s harder to inhabit the perspective of a different kind of animal, like a wolf. Philosophers like Thomas Nagel have argued that it’s either incredibly difficult or simply impossible to imagine how other animals experience the world, and this is evident in games that feature non-human avatars.

Twilight Princess tries to close this experiential gap by giving the player “wolf senses” to show them how Wolk Link sees the world through smells. But visually representing scent trails as glowing lines in dark landscapes doesn’t do much to make the player feel like an actual wolf: if anything, it gives them a sense of how a human would interpret the way that a wolf experiences the world, which isn’t the same thing as directly adopting a wolf’s perspective.

So, there ends up being a disconnect between the role that the player is meant to inhabit in Twilight Princess and the perspective that they actually have on the game’s world:

- Link, the player’s avatar, transforms into a wolf and presumably experiences the world as a wolf does.

- The player, with no experiential knowledge of what it is like to be a wolf, ends up either imagining the wolf as some kind of four-legged human, or instead simply viewing and manipulating the wolf as an object.

Now, it may be that the player is meant to imagine themselves in some role other than that of the avatar in Twilight Princess—but, as Laila rightly points out, “blank avatars” like Link are typically meant to allow a video game’s player to “insert themselves into the story and feel as if they are more personally ‘becoming’ the avatar.” A non-human avatar, like Wolf Link, typically impedes this kind of empathy between player and avatar because of the gap in how different species experience the world.

Okami gracefully overcomes this problem of non-human avatars by allowing the player to inhabit the role of a god. There’s no a priori reason to suppose that a god manipulating a wolf would know any more about what it’s like to be a wolf than the player herself would—and so the player of Okami ends up occupying a role through which she can authentically and fully engage the game’s world.

And, more to the point, this relationship between god, player, and avatar is what empowers the game to establish a robust metaphor between the religious history of Japan and the fundamental nature of video-game storytelling.

“Hegemony” is a Fancy Word for What Gamers Do

It’s obvious that many video games—from God of War, to Darksiders, to Okami—take many cues from mythology and religion. What I love about Laila’s work on Okami is how thoroughly it demonstrates that, far beyond acting as mere inspiration, myth and religion often serve as a crucial base of background knowledge that allows us to see the stories of video games in radically new ways.

While Laila illustrates the above point in many different ways throughout her article, I want to zero in on just one way that Okami uses religion to tell a special kind of story that could only work as a video game: the extended metaphor between the story of Okami and the political function of the Kojiki.

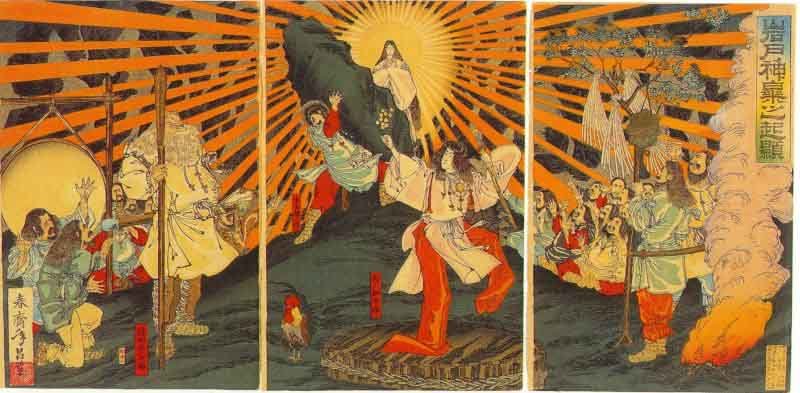

A classical image of Amaterasu emerging as the sun.

Laila points out (from a personal interview with Dan Hughes) that the myth of Amaterasu was more than just a myth in Japanese history: it was a linchpin in the Yamato clan’s strategy for securing political control of Japan.

The Kojiki is the source of Japanese mythology, heavily mixed with cultural control that established Japanese dynasty. Since Amaterasu is the best of the three gods that were born from Izanagi, the Japanese emperor was believed to be a direct descendant of hers—or so he said, in order to establish a dominant hierarchy in the Yamato clan. This mythology implied that, since other clans were not descendants of the most powerful deity, they did not deserve to rule Japan. The Emperor put the Kojiki together to prove the Yamato’s importance and status as the best among the rest of Japan, giving them the biggest excuse to rule Japan. This idea of Amaterasu’s divine lineage continued until the Emperor surrendered in World War 2.

This illustrates how the Kojiki was used to support hegemony: the enforced authority of one group (in this case, the Yamato) over others. If you’re trying to establish your own family as the Once and Final Kings of a country, propagating a text that directly connects you to the ultimate goddess seems like a good start.

Now, even if you’ve played Okami and appreciated its mythological inspiration, you might be indifferent to this anecdote about hegemony: it’s fair to suppose that, even if a myth informs a particular video game’s story, the politics surrounding the source myth won’t inform that game’s story. While that is a fair supposition, it’s a mistake in the case of Okami: we can combine the hegemonic function of the Kojiki with the player’s role as Amaterasu to understand Okami’s narrative in a new way that directly addresses what it means to experience the story through the medium of a video game.

To defend this claim, I want to zoom out of Laila’s analysis, which focuses on Okami’s reinterpretation of the Orochi myth, and instead focus on the bookends of the game’s story: the introductory sequence, and Amaterasu’s final confrontation against Yami.

The game frames its own story as an exploration of how people cope with myth and destiny. To see this, notice that the rise of Orochi and the shadows over Nippon is not due to some fluke occurrence, nor to some evil instigator: Orochi returns because of Susano-o, who removes his ancestor’s sword from its resting place out of a refusal to believe that the myth about his ancestor and a wolf defeating an eight-headed demon is true. Laila discusses this at length in her own work:

[Susano-o] wanted to disprove the legends: to show that there is no 8-headed monster actually sealed in a cave, and that no hero and wolf showed up and stopped the sacrifices. By proving that these legends are wrong, he believes, he can prove that he does not need to be a hero: “I was sick of hearing about how I’m a descendant of Nagi! I wanted to prove that it was all a lie by removing by removing the sword Tsukuyomi.”

Susano-o wanted to run away from an ancestral fate: he did not want to be destined to be a hero just because his ancestor was.

The entire conflict of Okami comes about because one character wants to abnegate his own heroic role in that conflict: Susano-o wants to be free to live his life free from the legacy of his ancestor, and thereby inadvertently thrusts himself into a story where he has to play the exact role of his ancestor.

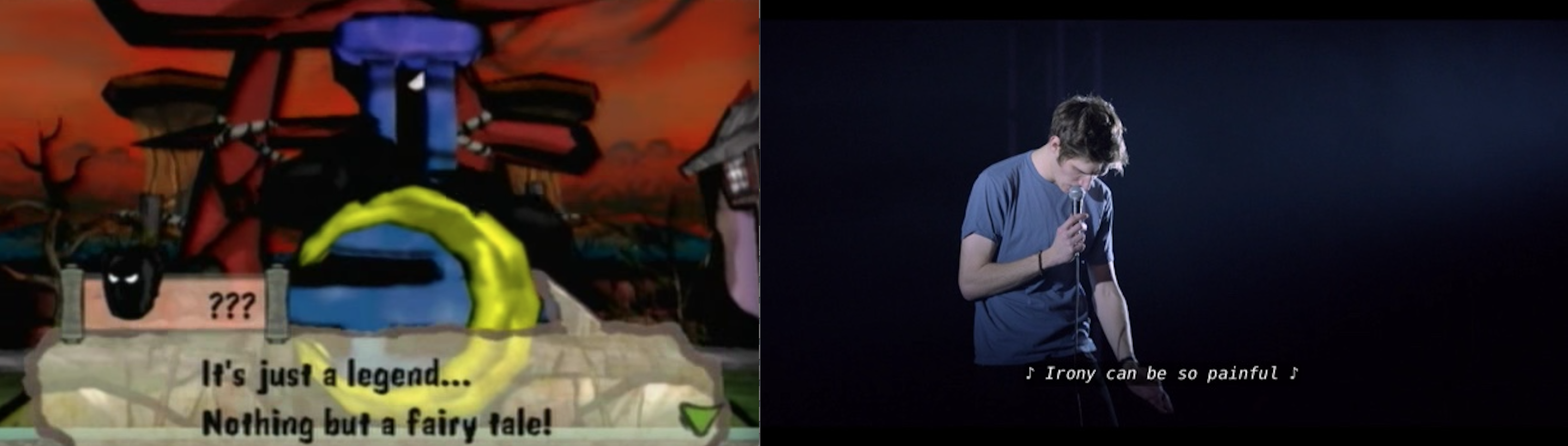

Susano-o rejects his heritage in the same breath as he incites history to repeat itself (left). (Thanks to Bo Burnham for doing my job for me (right).)

As the player progresses through the story in the role of Amaterasu, she’s not just pushing back the darkness of Orochi and Yami and saving Nippon: she’s also enacting and enforcing the myth of Amaterasu in a chaotic world that no longer believes in gods. Throughout Amaterasu’s journey, the player meets people who have given up on myth and salvation; and, by literally altering the world of the game via her avatar and the Celestial Brush, she reignites their belief in the gods by effectively retelling the ancient myth of Orochi, Nagi, and Shiranui. She finds towns and wilderness in chaos, and unites them under the sunlight and authority of the Amaterasu myth—not dissimilar to how the Yamato clan actually unified Japan by identifying themselves as descendants of “the most important god.”

This theme—the bringing of order to the game’s world through the reenactment of Amaterasu’s myth—culminates in the final confrontation against Yami. Yami is the literal antithesis of Amaterasu: while Amaterasu is the goddess of the sun and light, Yami is the physical manifestation of darkness. As we saw in the last section, the player of Okami occupies the role of Amaterasu; and thus you shouldn’t be surprised that Yami is also antithetical to the player and her quest.

Yami, the physical manifestation of darkness itself, is a fish in a fishbowl.

In the world of Okami, darkness, chaos, and nihilism are synonymous: Yami has drowned the world in darkness, which leaves society undone and leaves people estranged from their basic system of belief in the gods and sense of meaning in their lives. The bizarre form of Yami reinforces this triad of darkness, chaos, and nihilism: the ultimate antagonist in an epic saga of good-and-evil is a little fish in a fishbowl: flailing around in its limited environment, unable or unwilling to assign any meaning to its existence.

Yami doesn’t have the appearance of anything like a sentient Sephiroth, with complex motivations behind his apocalyptic actions: rather, Yami is an entity that has no understanding of what order and meaning even are, and this is what antagonizes him against Amaterasu, a divine entity that illuminates the world and invites order amongst its constituent peoples.

The hegemonic coups de gras in Amaterasu’s battle against Yami is the vivid cutscene in which Issun, the traveling artist and Amaterasu’s companion, uses his art to show everyone whom Amaterasu and the player helped that the white wolf was actually the avatar of a goddess, compelling them to believe in Amaterasu again and offer their prayers to her. Amaterasu is ultimately empowered to defeat Yami because everyone in the world comes to believe in her and the divine system of order that she represents, which consequently nullifies the orderlessness that Yami represents.

What does this have to do with the player and the nature of video-game storytelling? The battle between Yami and Amaterasu is a metaphor for what the player is doing as she progresses through the story of Okami—or, for that matter, through the stories of most video games. Video-game stories sit in the middle of a paradox: on the one hand, these stories must present worlds and characters that seem capable of evolving in many different ways over time: much like the real world, the worlds of games—if they’re represented well—seem like environments with people who all have their own desires, whose futures could proceed in any number of ways. Yet because a video game’s story centers on the actions of one character—namely, the avatar—all of the events and characters of the game’s world must ultimately bend to the actions of the avatar.

In this fundamental way, the actions of a video game’s player are hegemonic: they determine the course of events in the video game’s world, and they determine the fates of the characters in that world. They subordinate everyone else in the game’s world to the avatar. Okami is about that hegemony—a hegemony that, as Laila observes, perfectly mirrors the way in which the Yamato used the Kojiki for political gain.

The player of Okami enters a world that has thoroughly rejected the story she intends to tell: the very need for the player to save Nippon originated from the actions of a character (Susano-o) that was trying to deny that narrative of a god saving the world. The actions of the player—who is acting in the role of Amaterasu—proves the truth of that rejected story by example. This leads quite inevitably to the story’s conclusion: by the time the player reaches Yami, the game’s world is no longer a hospitable host for Yami because the player’s actions have imposed the exact kind of meaning and value on the world that the incarnation of darkness denies.

You don’t need to read Laila’s article and understand the hegemonic history of the Kojiki in order to appreciate the story of Okami. When you are familiar with this hegemony, though, a new way of reading the game opens up to you: in addition to thinking about the story of Okami itself, you can also now think about what it means for you, the player, to be telling this story—to be imposing this story on the world of the game.

Less Suspense and More Greek Tragedy

Okami puts you in the driver’s seat of the Mother Goddess and progenitor of all. There’s no question in this story of whether or not you will ultimately succeed in your quest to save the world. It’s a foregone conclusion that you will prevail. I think that this is a feature of storytelling we need right now: put simply, we need to return to Greece.

We live in an age where stories in all storytelling media jockey for our continued attention by teasing us with suspense-laden twists:

- Will the hero succeed in the end?

- Are the villain’s motives really as bad as we think they are?

- What’s the big, secret explanation for what’s really happening on that island?

There are a time and a place for suspense, and I don’t intend to deny suspense’s value here. But when suspense becomes a story’s central focus, it introduces a special kind of handicap for its audience: audience members end up getting caught up in trying to anticipate the story’s twist, and they don’t have enough remaining bandwidth to actually interpret the meaning of the events that are happening in the story’s real time. In this model of storytelling, consuming stories becomes more of an elaborate betting game than an interpretive exercise.

There’s a different, ancient model for storytelling. It’s the model that’s typical of ancient Greek theater, and it’s the model we see at work in Okami: characters all have unavoidable fates, and the audience knows what these fates are. This kind of story, then, is not interesting because we don’t know what will happen next: it is interesting because the audience has the job of unraveling the meaning of those inevitable events, and of how the characters react to them.

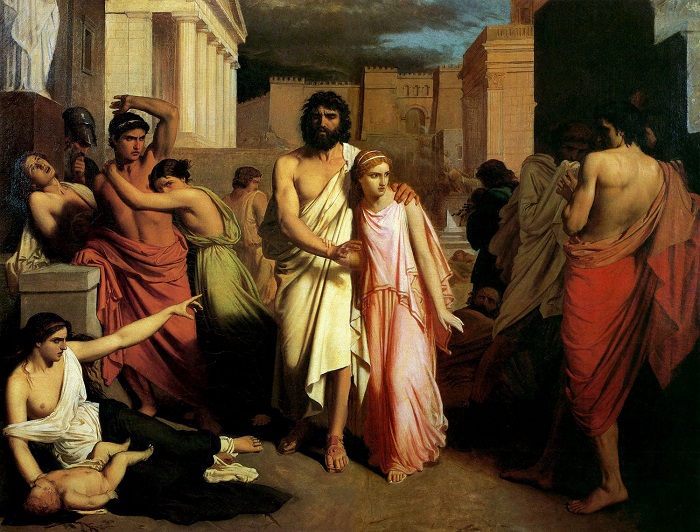

Oedipus and his daughter, Antigone, from the Oedipus cycle.

Jean Anouilh features a choral speech on this exact topic in his adaptation of Antigone, one of the plays in the Oedipus cycle; he refers to the suspense-driven model as “melodrama,” and contrasts it with the fate driven model of “tragedy.” I return to this speech often, and I think it’s worth sharing in its entirety here:

The spring is wound up tight. It will uncoil of itself. That is what is so convenient in tragedy. The least little turn of the wrist will do the job. Anything will set it going: a glance at a girl who happens to be lifting her arms to her hair as you go by; a feeling when you wake up on a fine morning that you’d like a little respect paid to you today, as if it were as easy to order as a second cup of coffee; one question too many, idly thrown out over friendly drink — and the tragedy is on.

The rest is automatic. You don’t need to lift a finger. The machine is in perfect order; it has been oiled ever since time began, and it runs without friction. Death, treason, and sorrow are on the march; and they move in the wake of storm, of tears, of stillness. Every kind of stillness. The hush when the executioner’s ax goes up at the end of the last act. The unbreathable silence when, at the beginning of the play, the two lovers, their hearts bared, their bodies naked, stand for the first time face to face in the darkened room, afraid to stir. The silence inside you when the roaring crowd acclaims the winner — so that you think of a film without a sound track, mouths agape and no sound coming out of them, a clamor that is no more than a picture; and you, the victor, already vanquished, alone in the desert of your silence. That is tragedy.

Tragedy is clean, it is firm, restful, it is flawless. It has nothing to do with melodrama — with wicked villains, persecuted maidens, avengers, gleams of hope, and eleventh-hour repentances. Death, in a melodrama, is really horrible because it is never inevitable. The dear old father might so easily have been saved; the honest young man might so easily have brought in the police five minutes earlier.

In a tragedy, nothing is in doubt and everyone’s destiny is known. That makes for tranquility. He who kills is as innocent as he who gets killed; it’s all a matter of what part you are playing.Tragedy is restful; and the reason is that hope, that foul, deceitful thing, has no part in it. There isn’t any hope. You’re trapped. The whole sky has fallen on you, and all you can do about it is to shout.

Now, don’t mistake me: I said “shout”: I did not say groan, whimper, complain. That, you cannot do. But you can shout aloud; you can get all those things said that you never thought you’d be able to say — or never even knew you had it in you to say. And you don’t say these things because it will do any good to say them: you know better than that. You say them for their own sake; you say them because you learn a lot from them.

In melodrama, you argue and struggle in the hope of escape. That is vulgar; it’s practical. But in tragedy, where there is no temptation to try to escape, argument is gratuitous: it’s kingly.

Despite being neither Greek nor tragic, Okami is like a Greek tragedy in this way. There is never any question of whether the player will succeed, and it is the absence of any such question that empowers us to instead think about what it means for us, as players, to be imposing our will and our myth on the unsuspecting, chaotic world of Nippon and Yami. It’s what empowers us to recognize the plot as a byproduct of our own hegemony, and to ask ourselves whether that hegemony is a good thing, a bad thing, or morally neutral.

This game taught me to expect more from “mythologically inspired” games. It’s easy to throw a few gods into a game as bosses, or to design a level based on a particular circle of hell. It’s a far taller order to tell a story that forces the player to reflect on what it means to create a myth, and—even beyond that—to make oneself a part of that myth.

We should demand that level of sophistication from mythic video-game storytelling.