The following is an entry in “A Comprehensive Theory of Majora’s Mask,” a series that analyzed the storytelling of Majora’s Mask from the time its 3D remake was announced to the time the remake was released. Find the full series here.

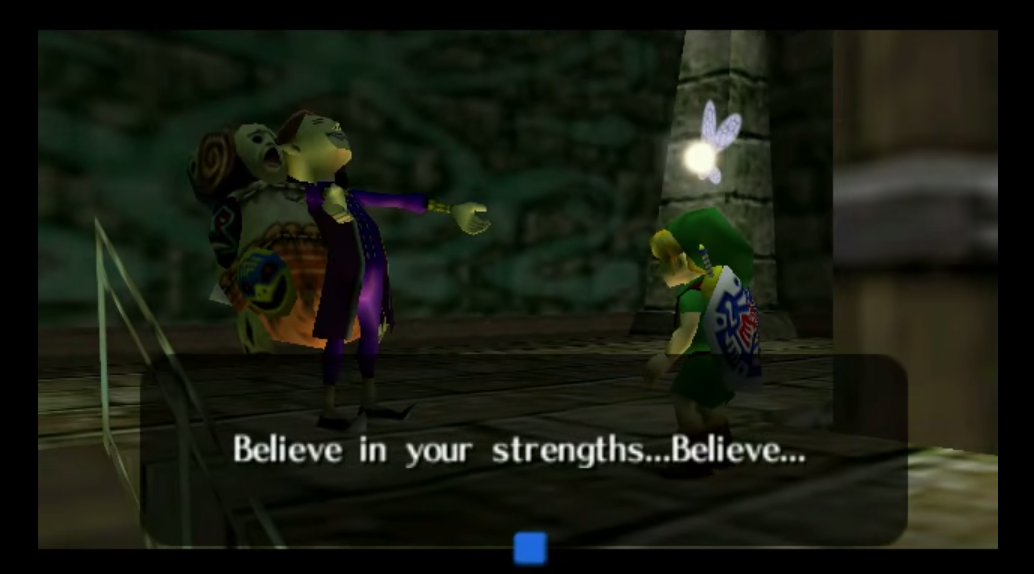

The most iconic line of “Majora’s Mask” is the very first line spoken to Link by the Happy Mask Salesman upon Link’s arrival in Termina: “You’ve met with a terrible fate, haven’t you?” To many, this line alone captures the essence of what it means to play “Majora”; here, the Salesman succinctly sums up Link’s sudden encounter with a dark parallel world. It’s one of the lines that leave a haunting impression on players long after the game has been put down. It’s also the namesake of my present analytic endeavor.

In today’s article, I offer the first in a series of analyses focusing on particular lines of dialogue within “Majora’s Mask.” I understand that, even for this project, such an enterprise might feel like over-analysis; however, I hope to convince readers to take a different perspective: after a lot of heavy, theoretical work, we have the background analysis to examine lines such as “You’ve met with a terrible fate, haven’t you?” in an illuminating way, with a new perspective unique to our overarching theses.

I have a confession to make to readers before proceeding: a significant portion of my theoretical approach over the past two months has been tacitly designed to provide the necessary machinery to examine this particular line of dialogue. This is because, as I will argue, the line does actually encompass a tremendous amount of what it means to enter into the world of “Majora’s Mask”; and, it may just provide insight to the world beyond the game. Before beginning analysis, I list the relevant theses I will be using, and where to find their first stipulation and defense.

1. The world of Termina become reality by virtue of Link encountering it. [Discourse on death in Termina]

2. There exists no substantive, metaphysical grounding for morality in Termina. [The metaethical thesis of “Majora’s Mask”]

3. There is an artificial perception of morality in Termina, focalized on Majora and catalyzed by the Happy Mask Salesman. [Argument for equating Majora with Termina’s concept of ‘evil’, analysis of the Happy Mask Salesman]

4. Link’s journey in Termina reflects inter-timeline soft determinism and intra-timeline agency, and intra-timeline agency is unique to Link. [Analysis of free will / determinism in Termina, revision of free will / determinism thesis]

5. The Happy Mask Salesman is ontologically responsible for Link’s agency within Termina, because he gives him the ability to heal his Deku form. [Analysis of Deku Link, analysis of the Happy Mask Salesman]

6. “Majora’s Mask” is framed by an unreliable narrator. [Third consequence of the theory of Garo as a marginalized race]

So much for background theses. This is the form that my line analyses will take. I will consider: the speaker of the line; the intended audience of the speaker’s words; the relationship between speaker and audience; and the content of the line itself. Lastly, I will synthesize these components to present an attempt at comprehensively explaining the line.

Regarding the speaker: I analyzed the Happy Mask Salesman last time, and argued that he functions as an entity that is metaphysically adjacent to Termina, and is responsible for Link’s agency, Termina’s fatalism, and Termina’s moral artifice. Not only is he generally crucial to the architecture of Termina, but he is also crucial to Link’s capacity to engage with Termina, both because of his teaching Link the Song of Healing and because of the motivational force of ascribed moral valence. We might say, then, that the analysis describes the Salesman as a speaker who both creates the problem of Termina — that is, the plot of the game — and prompts Link to solve it — and, to put it another way, motivates the player to play the game.

And who, exactly, is the audience of the Salesman’s words? The obvious answer is ‘Link’, but I think that what I just said above should give us pause: as we have discussed before, Link is less of a substantive character and more of an avatar that directly links the player to the universe of the game. Combine this with the Salesman’s position adjacent to the general domain of Termina, and I think we can plausibly interpret him as speaking both to Link and the player. I will flesh out a defense of this more in a moment, when I consider the line’s content.

As for the relationship between the Salesman and Link, it is worth noting that this is the line that directly establishes that relationship in “Majora.” It is this line that stops Link from exiting the Clock Tower into Clock Town, and prompts him instead to encounter the Salesman, who frames Link’s quest as a mission to reclaim a stolen mask, and to return to “normal.” In keeping with the theory of the Salesman as ontologically crucial to our conception of Termina, it’s not at all clear what would happen if Link were to exit the Clock Tower without encountering the Salesman; more to the point, it isn’t apparent that Link could enter Termina without encountering the Salesman. Analyzing the line’s content will explain what I mean.

“You’ve met with a terrible fate, haven’t you?”

Let’s suppose, to begin with, that the referent of ‘you’ is Link, ignoring the player. We are equipped with an explanation of what it means for Link to ‘meet with’ something in Termina: I argued in the examination of Mikau that Termina is brought into reality by Link encountering it [1]. Using this argument, we can gloss the meaning of ‘meeting’ as ‘creating through encountering’.

Turning to the subject, ‘a terrible fate’, we can understand it by parsing it in two parts: ‘fatalism’ and ‘terribleness’, which [4], [2], and [3] allow us to explain. I have defined ‘fate’ as the softly determined set of timelines constituting a given playthrough of “Majora,” within which timelines each particular Link possesses agency. ‘Terrible’, which I read as a moral term, is an instance (actually, the first instance) of the Happy Mask Salesman ascribing morality to a universe in which morality does not fundamentally obtain. Combining the terms, then, we find the concept of an artificial, negative moral gloss to the framework of a deterministic set of timelines, which Link is about to encounter.

Of course, the presumed referent of ‘a terrible fate’ is Link’s transformation into a Deku Scrub; is it plausible to expand the notion of ‘fate’ in this case to the timeline set? I think it is, because I see the transformation and timeline set as inseparable: it is the transformation of Link that leads him to learn the Song of Healing from the Salesman, thereby endowing him with meaningful agency within Termina, and also allowing him to proceed through the timeline set [5]. But of course, that ‘terrible fate’ comes hand-in-hand with intra-timeline agency, and Link’s ability to meaningfully alter the number of form of three-day cycles. Inseparable from the fate of Termina is Link’s capacity to act willfully.

This is what brings us to the end of the line, ‘haven’t you?’, which changes the tenor of the line from a statement to a question. In this phrase, the Happy Mask Salesman cedes his position of metaphysical authority by admitting uncertainty; even if the question is rhetorical, the tenor is fundamentally more tentative than if he were to say, for example, ‘You’ve met with a terrible fate, I see.’ That the phrase accompanies a statement that coherently reinforces the metaphysical and metaethical structure of Termina suggests that this may also be the first instance of narrative dissonance and unreliability in the game [6]. Moreover, the admission of fallibility from a figure that is architecturally crucial to our concept of Termina suggests that the narrative is aware of its own dissonance.

Synthesize these points, and we can gloss the Salesman saying “You’ve met with a terrible fate, haven’t you?” as follows: a metaphysical arbiter of Termina is fallibly claiming to the link between player and game universe (‘Link’) that he has brought a morally negative set of softly determined timelines into being by encountering it. But there is a seeming paradox here: how can an architectural fixture of a universe coherently inform someone that they have created that universe by encountering it?

The most compelling reason I find on this interpretation for believing that the Salesman is speaking to both Link and the player is that this relationship resolves the seeming paradox. The Salesman may narratologically justify and substantiate the limited agency of Link, but it is the player who is ultimately responsible for imparting that agency to Link. This is what makes the line, in my mind, so significant: beyond encapsulating the aesthetic dynamics of “Majora’s Mask,” it can be read as an argument for the nature of video games as a medium. The player turns on a game and is informed by the game that, in turning it on and engaging it, they have brought a universe to life; yet the persistence of the universe in contingent upon the player’s choice to continue playing the game. The game establishes a coherent universe, and yet the most basic authority of that universe must be ceded to the player. From that jumping-off point of narratological fallibility, other, more complex forms of narratological dissonance, such as the artifice of morality and the genocide of the Garo, may be posited, adding unique aesthetic elements to the game which cannot be achieved in other media. This is why I have chosen to make this line the namesake of my work on this blog: it is the open front door of gaming as a medium, inviting the player to create a work of art by mere virtue of experiencing it.

Continue Reading

- A Comprehensive Theory of Majora’s Mask series navigation: < “Dawn of a New Year, and the curious case of the Happy Mask Salesman in Termina” | “’He was lonely’: the pathos of Skull Kid” >