The following is an entry in The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake, a series that analyzes how and why the remake of Final Fantasy VII is a landmark innovation in both Final Fantasy and video-game storytelling more broadly. Read the series’ mission statement here.

At no point in Final Fantasy VII Remake can you stop and look up at the daytime sky.

Each of the 4 daytime segments of the game takes place underneath the massive plates of Midgar.[1] The only times when Cloud walks around the topside of Midgar (in Chapters 2, 4, and 16-18) are during nighttime. Otherwise, Aerith’s “steel sky” weighs down on the slums. Despite Midgar’s height, this still constantly feels oppressive; “Under the Rotting Pizza” is the name of one of the music disks in the game. As the stakes the party faces climb, the deepening night draws closer and closer, instilling a sense of dread around Shinra Corp’s activities. The daytime segments are lighter-hearted, but the darkness is never far off, always visible in the central pillars of Midgar.

This sense of dread is, however, far more deeply rooted than a day-night cycle. The game revolves around two moments of destruction: the disastrous explosion of Mako Reactor 1 and the collapse of the Sector 7 plate. Both take place in darkness, luridly illuminated by red flames. This hellish imagery in both is punctuated by NPCs claiming that the destruction feels like “the end of the world,” and even the unflappable Cloud is shaken by both.

I want to home in on that phrase “the end of the world.” Final Fantasy VII Remake is a game drenched in imagined and foreshadowed catastrophe. Sephiroth, following the characteristics of apocalyptic literature, guides Cloud and the player through the events of the rest of the original Final Fantasy VII, culminating in a singular, inevitable apocalypse. In the final act of the game, however, Aerith uses Buddhist ideas of enlightenment to reject the inevitability of Sephiroth’s end, setting up the primary thematic conflict that we’ll see in subsequent entries in the Remake series.

Before we get going, though: spoiler warning for both Final Fantasy VII Remake and the original Final Fantasy VII. Additionally, the ideas I discuss in this article are deeply tied to multiple religious traditions. These ideas are part of a cultural heritage that is being adapted into the fictional world of the game. The conflict I set up does not mirror any real-world conflict, nor does it condemn any real-world religions.

Apocalyptic Literature

In order to talk about the ways in which Final Fantasy VII Remake fits a very specific genre of literature, we’ll have to turn away from the game in order to introduce what I mean by “apocalyptic.” The obvious definition is that of a major destructive event, the end of the world, but that meaning actually was only introduced in the 19th century! Before then, the word “apocalypse” followed the Greek word: apokalyptein means “uncovering.” An elegant translation would be “revelation,” which is the name of what we now know as the most famous example of apocalyptic literature.

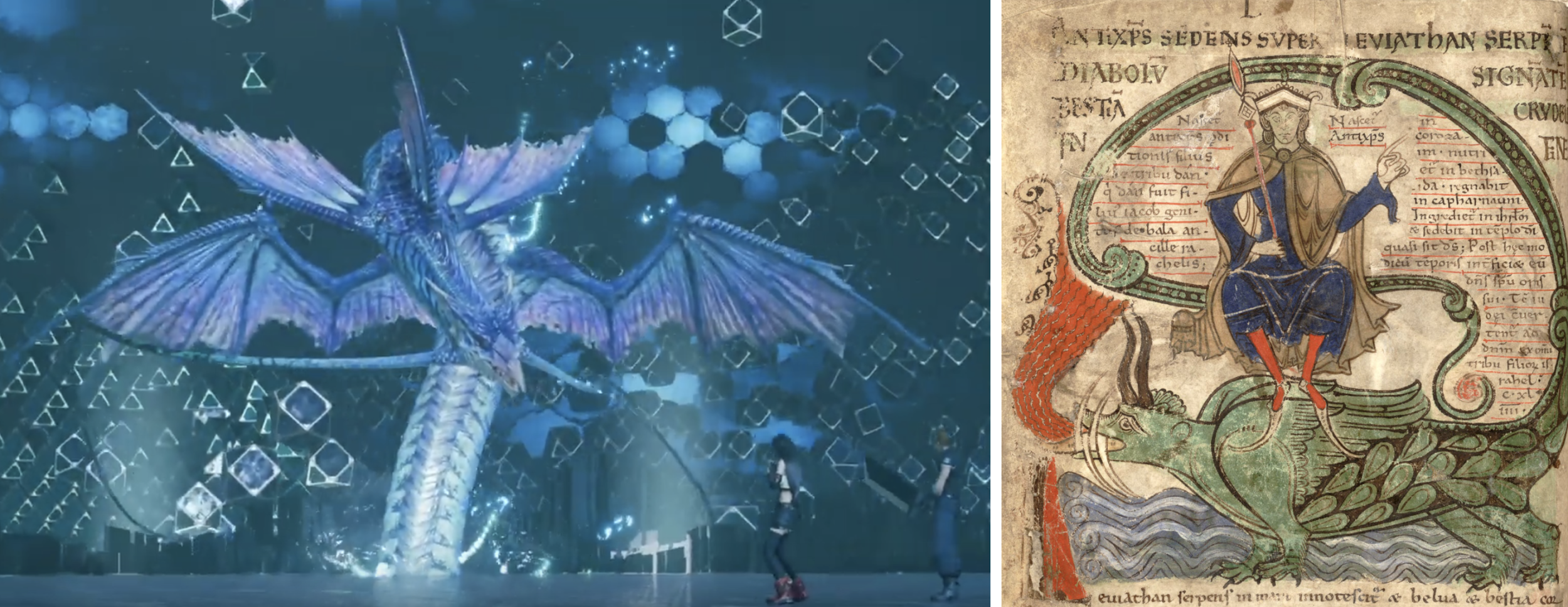

Scenes of Behemoth and the Draconic Stan from the Book of Revelation.

The final book of the Christian Bible is the Revelation, or Apocalypse, of St. John, telling of the day of Judgment and the second coming of Christ. This is framed as a vision granted to the apostle John by the angel Gabriel: a glimpse of the end of the world. In it, monsters and dragons appear, the world is consumed in several catastrophes, and then the divine crushes Satan forever and the promised heaven is revealed. The Book of Revelation is the quintessential example of apocalyptic literature, though it is hardly the only example of the genre: The Old Testament Book of Daniel contains apocalyptic visions in Chapters 7-12. This mode of storytelling was hugely popular in the early Christian world, but many of those stories (e.g., Enoch 3) were eventually dismissed as non-canon.

So, we have a few main characteristics of the apocalyptic genre:

- An angel or other divinely-linked entity grants the vision to the protagonist.

- Surrealist imagery, sometimes with fantastical beasts.

- Visions granted are of the end of the world and the aftermath.

Now, let’s return to Final Fantasy VII Remake and see how it possesses each of these characteristics. Sephiroth is our angel, summons are the fantastical beasts, and as for the visions… Well, there’s no shortage of visions to look at. But before turning to Sephiroth, let’s look at the apocalyptic nature of our summons.

Summoning Mythological Spirits

The summon list in Final Fantasy VII Remake is dramatically reduced from the original game, from 17 summons in Final Fantasy VII to a mere 6 in the remake. I argue that each of these in some way relates to the theme of destruction that the genre demands, and therefore can be read as support for the apocalyptic genre.

One stands head and shoulders above the rest as ultimately relevant: Fat Chocobo.

Truly a harbinger of the end times.

Okay, I’m mostly kidding. Fat Chocobo and Chocobo & Moogle can only be attributed to the necessities of the Final Fantasy franchise. The other four summons, however, all genuinely do have destructive connotations.

Ifrit: the term ifrit refers to a type of Arabic spirit, related to the category of jinn. Ideas of the ifrit vary dramatically based on region, but in rural Egypt, according to folklorist el-Sayad el-Aswad, an ifrit is the ghost of a person who was killed, and is tied to violent, destructive emotions. The ifrit and the rest of the soul will be reunited on the Day of Judgment.[2]

Shiva: Shiva is one of the three primary Hindu deities in the present day, alongside Brahma and Vishnu. While there is a lot of variation, many of the puranas describe Brahma as the creator of the world, Vishnu as its guardian, and Shiva as its destroyer.[3] (Side note: Shiva is male, not a magic ice lady, though he can merge with his wife into an androgynous deity).

Leviathan: This entity appears in the Old Testament of the Hebrew Bible as a destructive force that takes the form of a sea monster. Leviathan appears a few times in the Old Testament: the Book of Job describes how powerful he is, with flaming breath and impenetrable scales, while the Book of Isaiah, Chapter 27, claims that he will be slain on the Day of Judgment, linking him to the beings described in the Book of Revelation.[4]

Bahamut: Bahamut appears in the 13th-century Arabic cosmographies as a part of a very abstract conception of the world. In this conception, compiled by Edward Lane from al-Qazwini and Yakut al-Hamawi (and others), Bahamut/Balmut is a giant whale that supports a bull that supports an angel that supports the world, which is about as Discworld as you could ask for. Bahamut drinks the water that falls off the world,[5] and when he is full, he will become agitated and start the Day of Judgment.[6]

Each of these four, then, is related directly to the end of the world, though some play a more active role than others. This is suggestive, but even more so is the absence of a staple series summon, the lightning spirit Ramuh. Ramuh, or Ráma, is one of the stereotypical princes-saving heroes in Indian mythology and an incarnation of Vishnu, the preserver of the world. Therefore, his presence would act counter to the destructive nature of the rest of the summons.

By providing this smorgasbord of apocalyptic monsters, the game fits that category of apocalyptic literature, emphasizing just how high Sephiroth intends to raise the stakes for the world.

One-Winged Angel

It is not an exaggeration to claim that Final Fantasy VII Remake is completely framed by Sephiroth’s presence: the very first strain of music in the entire game is the theme “One-Winged Angel” and he is the final boss of the whole game. However, his physical presence is almost non-existent! Mostly, he is there in drifting feathers, hallucinations, and visions, whispered voices into Cloud’s ear.

Sephiroth is, of course, an angelic figure by design. His single wing, though black instead of white, is the same shape as typical Renaissance angels, and his form in the original game looks much like a Seraph, one of the higher orders of angels.

Sephiroth, Final Fantasy VII.

Seraphim, Cefalu Cathedral, Sicily, 1300s.

It is fairly straightforward to interpret Sephiroth in this way, particularly in Final Fantasy VII Remake. It is not nearly as easy in the original Final Fantasy VII, where he is the source of fewer visions and his link to Cloud is left hidden until near the end of the game, long after Midgar is left behind.

Final Fantasy VII Remake establishes a link between Cloud’s visions and Sephiroth from the very first chapter: before the Scorpion Sentinel, Cloud is struck by a headache and green-tinged vision in which a single black feather falls. In Chapter 2, it is even more explicit: Sephiroth appears as the burning cityscapes of Midgar and Nibelheim fuse, in the longest vision in the game. When Cloud tries to attack him, Sephiroth and the flames vanish, at least until Aerith appears. These scenes establish that the visions are manifesting Sephiroth as he reveals new information of what is to come.

I here specify Sephiroth as the game’s apocalyptic herald rather than the Whispers, even though Red XIII identifies the Whispers as the arbiters of fate. However, in the final battle of the game, Sephiroth demonstrates an ability to, in some way, command Whispers, as he sends them to attack the party. They therefore can be interpreted as operating in a similar vein; their existence is tied to helping him succeed, and the few visions caused by the Whispers lead back to the apocalypse Sephiroth is working towards.

Visions of Apocalypse

Speaking of the visions, the contents of them, not just their framing, are often apocalyptic. The opening cutscene shows the wastelands around Midgar, the decay of the city, the wilting flowers, and the squalor of the slums—all in the first minute or so of the game. It is a dying world, even as green mako flames reflect in a child’s eyes.[7] This is Midgar as Sephiroth sees it, a place that deserves its apocalypse.

The revelations begin with Sephiroth’s appearance in Chapter 2. This is perhaps the most straightforwardly apocalyptic, with the scorching flames and Sephiroth’s talk of the planet dying. Even as he claims to be sad about it, he takes obvious delight in recalling Nibelheim’s burning and the slaughter of Cloud’s mother. He taunts Cloud to accept this fate, asking him to “run away. You have to leave. You have to live.” This sets the tone of inevitability: all Cloud can do is run if he hopes to survive what is coming.

Inevitability follows the two other significant visions of the first part of the game. When first arriving in the Sector 7 slums, Cloud is struck by a vision of a steel girder falling towards his head, which foreshadows the fate of the slums. The second takes place when Cloud learns Aerith’s name and that she has materia. He sees a vision of materia bouncing off the floor, which is part of her death in the original game. The first vision emphasizes that these are events that will happen; despite the team’s best efforts, Sector 7 is still destroyed. People who are familiar with the original game also know the inevitability of Aerith’s death. By revealing this vision earlier, Sephiroth makes a promise: the end of the world is coming, and there is nothing to be done. Aerith herself knows this; her resolution scene in Chapter 14 strongly implies that she, too, is aware that she will die, and aware of the consequences that will come from it.

The vision of Sector 7’s collapse is crucial to this reading of the game. There is a lack of visions in the middle hours of the game, from entering Wall Market up until the plate’s collapse. Cloud, Aerith, and Tifa are very much engrossed in the enormity of their task, trying to resist fate. Once they learn about Shinra’s plot from Don Corneo, the next hours offer a mad dash through the sewers and the train graveyard to prevent what was fated from coming to pass. They fail.

This offers a test, a small revealed cataclysm. Since this really is the end of the world for the inhabitants of the destroyed slums, it also serves as a testament to the truth of the visions. Even if Sephiroth comes and goes like smoke, the visions themselves are things that will yet happen. This is the emotionally lowest point of the game; the game made Cloud and the player care about Sector 7, even though it showed what was coming. That is a crushing blow, and one that the game dwells in; the emotional suffering of this apocalypse is no whisper. At this point, there is no alternative, and the game will twist that knife one more time.

As we reach the climax of the game, Sephiroth’s first plans come to fruition, and he has his peak apocalyptic moment. Sephiroth hijacks the Shinra propaganda video to show the devastation of Meteor, Aerith’s death again, and the destruction of Midgar. This is the ultimate moment of revelation: a fully pre-rendered cutscene shows the planet blowing up.

One other scene seems to be a foreshadowed vision of the original game. In Chapter 15, at the top of the Sector 7 ruins, Cloud, Tifa, and Barret overlook the destroyed sector and mourn its loss. This is a scene of steel devastation, framed in the red gold of sunset. In posing and overlook, it is a near-perfect mirror of the post-credits scene of the original game, which shows Red XIII and his descendants overlooking Midgar. However, instead of being from the planet’s view, where green returned to the city, the red and grey color palette shows the tragedy inherent in it. The human cost of this cataclysm is unthinkable, and yet it will happen.

The lead-up to that post-credits scene of the original Final Fantasy VII is revealed in a vision conferred by the Whisper Harbinger during that penultimate boss fight, and Red XIII calls it “a vision of what will happen if we fail here today.” At this point, the party has chosen to sidestep the apocalypse, for reasons I explain later in this article, but Red XIII makes it clear that these events are fated to happen; the imagery and visions present in the game are portents of the future.

The overlook of Sector 7 in Final Fantasy VII Remake.

The Advent Children version of the post-credits scene from the original Final Fantasy VII.

I have one final piece of evidence for classifying Final Fantasy VII Remake as apocalyptic literature. The very logo of the game shows Meteor, the incoming disaster. Meteor is a reference to medieval apocalypticism as well! The appearance of individual meteors or comets (i.e. those not in meteor showers like the Perseids) was perceived as a bad omen, presaging disasters.[8] Modernity has only strengthened this association, with the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs being the premier image of destruction. Therefore, even the central conflict of the Final Fantasy VII franchise is directly tied to apocalyptic imagery within the apocalyptic tradition.

Dread and New Hope

At this point, it is hopefully clear that Final Fantasy VII Remake presents a vision, revealed by Sephiroth, of the end of the world. The Whispers (including the Harbinger, whose very name means a herald, usually of catastrophe) are tied to Sephiroth, and are mostly working towards the same apocalypse he is. Sephiroth seems to have control of the situation through to the very final moments of the game. Even as the party “defeats” him, in a gameplay sense, he finds room to taunt Cloud once more, standing at the edge of creation. He is, it seems, inevitable.

The sense all this apocalyptic imagery gives is one of oppressive dread. Just as the sun is hidden, so too is hope, beneath the crushing weight of Midgar, the suffering it inflicts on the planet and on its people. The characters all feel it; all three versions of the secret scene outside of Aerith’s house in Chapter 14 dwell on this suffering in some way; Tifa mourns the flower Cloud gave her, Barret imagines the struggles his surviving companions in Avalanche will have, and Aerith mourns the inevitability of death. And, because the game embodies apocalyptic literature so thoroughly, the player is brought into that inevitability and horror too.

Hope is in very short supply after Sector 7 falls. Sephiroth neglects to ever reveal what the world might look like after his apocalypse. All that exists ends with Meteor, it seems, and it is impossible to conceive of anything beyond the immediate goal of rescuing Aerith from Hojo. Even after that, destruction awaits.

Alternatives to Apocalypse

At this point, the careful reader may have noticed that some parts of Final Fantasy 7 Remake don’t quite fit with this conception of the game as apocalyptic literature. The most prominent inconsistency lies with the Lifestream, which implies a form of reincarnation that cannot be squared away with a single moment of judgment. And you would be right! Final Fantasy VII Remake cares deeply about the rejection of the inevitable—the rejection of the Whispers’ lived destruction—and that holds true here as well. Careful analysis of these inconsistencies, down to revisiting the very structure of Midgar itself, reveals an entirely different worldview that is incompatible with and superior to Sephiroth’s end of the world. In order to discuss this alternative, though, we need to turn away from early Christianity to Buddhism, specifically the concepts of samsara and dharma.

Samsara and dharma are two extremely difficult terms to translate out of Sanskrit, but they are core ideas of Buddhist philosophy.[9] Samsara is the easier of the two: it is the cycle of death and rebirth, the endless reincarnation from which enlightenment allows us to escape. In the Buddhist tradition, life is, by definition, suffering, and all living beings are forced to endure this emotion-filled, sorrowful existence.

Dharma, however, is extremely difficult to translate. It refers to several things, but most importantly, it is the rules by which you can live a good life. There are eight broad strictures, from good acts to good mindfulness. Explaining them all here would be irrelevant, but it is crucial to understanding the path to enlightenment. The ultimate goal of dharma is the cessation of desire, at which point the true reality can be perceived and Nirvana attained.

So, what does this have to do with Final Fantasy VII Remake? Well, take a look at the design of Midgar. It consists of a circle, divided into eight, with a central tower. This design (segmented circle with central piece) is associated with the visual iconography of both samsara and dharma, though dharma offers the closer parallel.

Samsara

Dharma

Midgar

This is a clear visual parallel to dharma, but the wheel of samsara only contains six sections! This, however, is no obstacle; Midgar is composed of two circles stacked. Sectors 6 and 7 are destroyed by the end of the game on the upper layer, but the game goes to great lengths to show Sector 7 being rebuilt. Therefore, the top circle contains 6 inhabited circles and the bottom contains 8, suggesting samsara weighing on dharma. This visual similarity offers grounds for further consideration of whether Midgar can be viewed as a metaphor for each of these concepts, and, if so, how to interpret the game in light of them.

Reincarnation, the core of the circle of samsara, is present in Final Fantasy VII Remake in the form of the Lifestream, from which mako energy is taken. The Lifestream is an entity to which all people “return to” when they die (and therefore were taken from when they were born). Even though they are born into the surveillance of Shinra and all the suffering that I outlined earlier, they die and are born yet again. The Lifestream is the core of the planet in Final Fantasy VII, and therefore, in this adaptation, samsara can be interpreted as the world. While individuals can be trapped outside of the Lifestream, like Jessie’s father, this is not a good thing; a person will not reach their full potential cut off from the source in this way.

Interestingly, Midgar’s very name reinforces this interpretation. The name ‘Midgar’ is a corrupt spelling of the Old Norse ‘Miðgarðr’, which is to say the human world of Norse mythology. Midgar, therefore, can be understood to be an exemplar of the cycles of birth, suffering, and death that make up the world.

The very center of this metaphorical wheel of samsara, then, is Shinra tower. This is entirely appropriate: people are trapped in samsara because of their desires, and nobody in the game desires more than the Shinra executives. They desire power with which to escape and found a new, better version of Midgar. However, ironically, their desire to achieve enlightenment, to reach the Promised Land, is the very thing keeping them trapped in the cycle.

Dharma can be seen in the way characters act. Throughout the game, NPCs can be heard complaining about the inconveniences that the plot (and life in general) inflicts upon them. One character never complains, though: Aerith. She is unerringly positive about the world around her, and that outlook shows. Everyone in Sector 5 likes Aerith, and she seems to even get along decently with the Turks!

We don’t see Aerith enough to demonstrate that she follows all eight parts of dharma in FF7R, regrettably—though it is likely—but if dharma as a whole is generously interpreted as “living a good life,” then it definitely applies to her. In fact, it seems that most people in Midgar at least try to stick to the path! Apart from the cartoonishly evil elite, in Shinra Corp and Wall Market, most people are decent folk! They aren’t perfect, but then again, they aren’t Ancients, like Aerith is.

Aerith recognizes how good most people in Midgar—and, indeed, the whole world—are. While crossing the rooftops, she tells Cloud. “People hate the steel sky, the slums… but I don’t. How could I? All that passion, all those dreams, flowing and blending together into something greater.” This line is important! Aerith does not suffer underneath samsara, unlike most others. Instead, that “steel sky” motivates Aerith, encouraging her to live a good life, and to raise others in the slums to do the same. Her love for the slums shows how they can embody dharma, and the very human experience of trying to live according to it.

By serving as this positive role model to everyone she meets, Aerith is filling the role of a bodhisattva, an enlightened human who endures samsara to guide others to salvation. This takes passive forms, by letting Cloud do some of the side quests in Chapter 8, but also more active forms, as immediately before the Whisper Harbinger fight. The Whispers cry out, and Aerith says:

What you heard just now was the voices of the planet. Those born into this world. Who lived and who died. Who returned. They’re howling in pain.

She blames this on Sephiroth; his singular apocalypse causes suffering, and he does not care. The “salvation” that he promises is a threat, not an act of preservation. Aerith, existing in a state of enlightenment, recognizes the abrupt cessation of human life as bad for the world, preferring the gradual path of all things towards enlightenment.

And so we return to the idea of revelation, and of the end of the world. Unlike in the Christian tradition, there really is no conception of an “end” in the Buddhist tradition. Samsara endures, and individuals, such as the Buddha, can manage to escape that cycle, a goal for all people. Eventually, then, perhaps, the world would end when all beings have escaped, but that is not a topic dwelt upon. In terms of Final Fantasy VII Remake, this implies that there is no apocalypse. The world simply continues, until whatever state of being that was promised in the Scriptures of the Ancients is reached.

The End… of the article.

Final Fantasy 7 Remake, I have argued, references two real-world religious traditions in its generic and visual design. On the one hand is Christian apocalyptic literature, representing the point of view of Sephiroth, and on the other is the Buddhist tradition of reincarnation and eventual escape. These two are not entirely exclusive, to be clear: the dread of the apocalypse is part of samsara, as it causes suffering and attachment. However, the ultimate visions are opposed: one perceives a singular calamitous ending, while the other foresees a continuation, a never-ending cycle.

Aerith naturally stands as an alternative to Sephiroth, then; both are guides along incompatible visions of the future. However, much like Sephiroth, Aerith is not necessarily reliable. When we first meet her, in Chapter 2, she claims to not know what the Whispers are, despite later explaining exactly what they are. The game implies that she lied to Cloud from the very beginning, if only because he is not ready.[10] Sephiroth further induces doubt: when Aerith accuses him of being wrong, his response is enigmatic: “Those who look with clouded eyes see nothing but shadows.”

The player and Cloud alike are trapped between these two viewpoints. While the final act of Final Fantasy VII Remake presents Aerith’s conception of reality in detail, much of the rest of the game sets up the inevitability of the visions. Until the very end, the characters have to endure against the dread and horror of what is coming. Suffering, samsara, Midgar itself looms over the city, attempting to crush hope. Cloud has to choose between his two guides. Luckily, it’s not much of a choice.

Despite Sephiroth’s attempts to introduce doubt, the game constantly tips its hand in the very clothes they wear. Sephiroth is associated with black, while Aerith is white, associations of evil and good, respectively. This appears obvious—of course the main villain is associated with evil! But, this means that at every appearance he is an inversion of an angel, which undermines his claims to apocalyptic authority. Aerith, in contrast, maintains the imagery of a glowing, guiding light, making it very clear which conception of reality is true.

Ultimately, Sephiroth reveals too much. His apocalypse does not cause the end of evil and the salvation of the good: it causes only him and Cloud to endure. Ultimately, his visions are of a perfectly selfish ending; at the end of the game, he states “All born are bound to her. Should this world be unmade, so too shall her children.” However, at the edge of creation he claims that “I… will not end.” These two, in conjunction, indicate that he seeks to shatter his chains to the planet. The suffering of the world will be obliterated and reforged so that he will endure.

The trappings of apocalyptic literature in Final Fantasy VII Remake, in the end, topple at the final step. The Day of Judgment, though repeatedly promised, has no salvation to speak of. The souls of the planet shall howl in torment forever, rather than the good being raised to the promised land. And so, despite his power, Sephiroth, too, is simply trapped in the same suffering as everyone else. He knows that there is a beyond, but not how to reach it, and so his visions assume that the only way to escape samsara, the rot of Midgar, is to destroy it all in fire. Aerith shows that is clearly not the case, and so any appeal of Sephiroth’s visions collapses, proving that everything about him is wrong.

And so, the battle against the Whisper Harbinger, while the Whispers swirl and howl like souls at Judgment, offers a resolution against the dread of the game. When Aerith asks them to, at the very edge of Midgar, the party makes a choice to step forward from under the shadow of the city and reject their fate, and so may be defiant against all reason. And indeed, it is a full rejection, as Aaron Suduiko has argued on the site. My reading of the Whispers and his exist in tandem; regardless of what the Whispers are, they promise Meteor. And so, defeating them and a version of Sephiroth, the party steps out into the open sunlight for the very first time, escaping the cycle of suffering Midgar stands for.

And yet, the party looks back as they do so. Each of them is still tied to the city in some way. Aerith with the steel sky of dharma and her mother, Barret and Tifa with Marlene, Biggs, and the hope of a new bar, and Cloud with his enemies, Shinra. They look back at their old reality, perceiving it for the first time as it really is, without the subconscious dread Sephiroth has imposed on them. And so, stepping away actually lets them perceive dharma, the proper order of reality, and hold it close to them as they continue their journey.

Choosing to embody these Buddhist philosophical ideas inevitably means a rejection of the Christian-inspired fated ending. This is, in my opinion, the primary metaphysical conflict that we will witness in the rest of the Remake series: the clash of two incompatible views about the end and purpose of the world. By defeating the Whispers, the party evaded the inevitability of Sephiroth’s revealed visions. Sephiroth admits as such; after defeating him in battle, Cloud starts to have another vision, but Sephiroth himself stops it, saying “that which lies ahead… does not yet exist.” He does not have any more visions of apocalypse to show, beyond the end of Creation that he and Cloud stand upon.

At the end of Final Fantasy 7 Remake, the state of the world is a paradox. Sephiroth and Aerith offer mutually incompatible understandings of reality, and both of them, at various points throughout the game, are proven to be right. Sephiroth is revealed to be deranged, desperate to free himself by sacrificing the world, while Aerith offers a life-affirming path forward. However, choosing Aerith’s paradigm does not eliminate the potential of destruction, only its inevitability; the tension and ambiguity are left hanging to be resolved in future games.

Rejecting fate is not the same as averting it. Even free of the dread that made Sephiroth’s visions appear to be perfect foreshadowing, Sephiroth was proven right once before. Jenova’s arrival destroyed the Ancients, and Sephiroth still thinks the planet will die while he endures. He may still be right; he is still out there. Rain falls on Midgar.

- These daytime segments occur in Chapter 3 (night is Jessie’s mission), Chapter 5 (night falls while they’re on the underplate, Chapter 8 (Wall Market, plate collapse, and rescuing Wedge is all one night), and Chapter 14 and 15 (night falls as Cloud, Barret, and Tifa reach Shinra tower). ↑

- El-Saya el-Aswad, Religion and Folk Cosmology: Scenarios of the Visible and Invisible in Rural Egypt, 2002, pp. 103-104. ↑

- Jan Gonda, “The Hindu Trinity.” Anthropos 63/64 (1964), 212-226. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40457085. ↑

- Leviathan is not mentioned by name in the book of Revelation, but later commentaries, including one by Thomas Aquinas, link Leviathan to the thing. ↑

- This doesn’t mean that they actually thought the world was flat; this is symbolic. ↑

- Lane, Edward William. Arabian society in the Middle ages: Studies from the Thousand and One Nights. London: Chatto & Windus (1883). ↑

- For a more detailed account of the opening sequence of the game, check out Dan Hughes’ article on this very site! ↑

- Olson, Roberta. “…And They Saw Stars: Renaissance Representations of Comets and Pretelescopic Astronomy.” Art Journal 44, no. 3 (2014), 216-224. ↑

- Special thanks to Dan Hughes and Aaron Suduiko for their assistance with interpreting this section. ↑

- This is actually consistent with the behavior of a bodhisattva. They teach according to a principle known as upaya, or “expedient means,” which means that they do not need to stay strictly to what is true, if so doing guides the pupil towards enlightenment properly. ↑

Continue Reading

- The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake series navigation: < “The Language of Trophies in Final Fantasy VII Remake″ | “The Drawing Board: The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake, Article Postmortem #1” >

1 Comment

Skylar · February 22, 2021 at 7:08 pm

WOW!

This article was extremely helpful in writing my essay on this exact very subject for my speculative fiction class.

So thank you!