The following is an entry in The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake, a series that analyzes how and why the remake of Final Fantasy VII is a landmark innovation in both Final Fantasy and video-game storytelling more broadly. Read the series’ mission statement here.

Narrative innovation is achieved by turning the non-story into story.

The story of video-game-narrative innovation, in particular, is one of transforming mechanics originally developed either for gameplay or marketing purposes into new storytelling devices. This is what Hidetaka Miyazaki accomplished when he effectively led the charge in transforming DLC from a cash-grab into a medium capable of telling stories that would be impossible to tell any other way; this is something we’re gradually witnessing in the evolution of the trophy and achievement system in games.

Trophies began as a way of merely acknowledging players completing certain objectives within games—and a way for players to broadcast to their friends how much of any given game they’d completed.[1] Over time, they grew into sophisticated systems for inspiring, inviting, or nudging players to complete certain tasks.[2] Today, they’re morphing into sophisticated commentary that can radically change the meaning of a game’s story—and that’s where Final Fantasy VII Remake takes the stage.

I want to convince you that Final Fantasy VII Remake’s trophy system isn’t merely a design tactic for lengthening the time a player spends with the game, nor is it merely a way of motivating players to explore areas of the game they otherwise wouldn’t: in fact, Final Fantasy VII Remake’s trophy system offers a surprising interpretation of our relationship to the game’s key themes, changing our understanding of the game’s story and our role in it.

I’ll start by providing an example of how trophies can change the meaning of a game’s narrative and show how that kind of trophy system can function as an interpretive lens through which we can view the substance of a game’s story differently. Then, I’ll show how Final Fantasy VII Remake’s trophy system offers a challenging interpretation of our role in the storytelling of the game—an interpretation at which we would not arrive if we were to play the game without the presence of any trophies. Finally, I’ll consider some ways in which this kind of trophy-based storytelling could be cultivated further in subsequent entries in the Final Fantasy VII Remake series—and, indeed, in gaming more generally.

(Be advised that a spoiler warning is in effect for Final Fantasy VII Remake, Final Fantasy VII, Dark Souls, and Hollow Knight. The names of non-hidden trophies from Control, Code Vein, Final Fantasy XV, and Call of Cthulhu are also mentioned.)

Trophies as an Interpretive Lens

Over the last few years, trophies have been maturing from a ledger of tasks into a lens for interpreting a game’s story in a new way.

My favorite example of how trophies have matured comes from Matt McGill’s lecture at With a Terrible Fate’s PAX East 2020 panel, “Dark Souls of X: What Makes a Successful Souls Successor?”: in the course of comparing and contrasting Dark Souls with Hollow Knight, McGill invites the audience to consider how Hollow Knight does a great deal more storytelling with its trophies than the first Dark Souls did.

McGill points out that most Dark Souls trophies are merely descriptive in the sense that the trophy names and descriptions identify, in a fairly neutral way, a certain action that the player and/or avatar completed in the plot.[3] When you defeat Gravelord Nito or the Bed of Chaos, for instance, you’re awarded trophies that are aptly named “Defeat Gravelord Nito” or “Defeat Bed of Chaos,” respectively.

Dark Souls is groundbreaking in many regards, but it is not especially innovative in its repertoire of trophies.

McGill contrasts these descriptive trophies with what I’ll call interpretive trophies in Hollow Knight: trophies that change the meaning of an event(s) in a game’s plot to give the player a perspective on that event(s) that she may not have otherwise had.[4] The example that McGill uses is that of the “Respect” trophy in Hollow Knight, which the player earns by defeating the Mantis Lords, the arbiters of the remote Mantis Village, in a duel.

As the player earns this trophy, the bested Mantis Lords bow to the Knight (the player’s avatar), and the various gates throughout the Mantis Village open. The other mantises who inhabit the village, previously hostile to the Knight, now bow whenever the Knight approaches.

The Mantis Lords bow to the Knight after the Knight defeats them in combat.

McGill rightly observes that this “Respect” trophy colors the story of Hollow Knight more richly than the “Defeat the Soul Lords” trophies color the story of Dark Souls: to paraphrase him, the notion of earning respect inspires players to think more critically about who these Mantis Lords are, how they got in the positions that they did, and how this victory—one of earning respect—corresponds to the tasks that the Knight is expected to complete elsewhere in the game. In so coloring the game, the “Respect” trophy also functions as an interpretive trophy in the sense that it narrows the field of possible interpretations available to the player, leading them to see an otherwise vague event from a perspective specified by the name and description of the trophy.

To see what I mean by this, imagine that you defeated the Mantis Lords and witnessed all the mantises bowing to the Knight without the addition of the “Respect” trophy. In that case, the mantises’ behavior could be explained a number of different ways:

- Maybe the Knight earned the mantises’ respect, which they’re demonstrating by bowing to him and allowing him access to their village.

- Maybe the Knight intimidated the mantises into a state of subservience, compelling them through force to submit to his will.

- Maybe the Knight exposed the mantises as cowards, shrinking in fear after he bested their leaders.

Without the trophy, the meaning of the mantises’ gestures and behavior after the defeat of the Mantis Lords would be vague in the sense that the player would not have grounds to determine which of the above possibilities was actually the case. With the trophy, players have a decisive interpretive clarity that they would otherwise have lacked: they know that they have earned the mantises’ respect.

By giving the player a new perspective on the story in which she’s participating, the “Respect” trophy of Hollow Knight is narratively significant in a way that the “Defeat the Soul Lords” trophies of Dark Souls are not. All the same, you might think that the Hollow Knight’s trophy doesn’t do all that much narratively, even though it does more than Dark Souls’ trophies. After all, it’s not providing the player with a totally new semiotics of the story’s events: it’s simply identifying one of the possible semiotics the player may have already been contemplating as “the correct one.” For a trophy system to really come into its own as a storytelling tool, you might think, the trophy system needs to give the player a perspective on the story that she never even would have considered as a live possibility without that trophy system.

That’s the exact achievement that Final Fantasy VII Remake unlocked—if you’ll pardon the pun.

How a Trophy Called “Master of Fate” Undermines Your Ability to Master Fate in Final Fantasy VII Remake

Final Fantasy VII Remake developed a system of interpretive trophies that redefines the player’s role in the series. It did so in a way that may have ramifications for future games in the series—and, indeed, for future video-game storytellers who take up the task of further innovating in trophy-based storytelling.

The key to the success of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s trophy-based storytelling is its platinum trophy, “Master of Fate,” which the trophy system exploits to subtly redefine the player’s understanding of what she can and cannot influence within the purview of the game’s world.

This platinum trophy—the trophy that marks the acquisition of all the other trophies in a given game—follows what’s become something of a convention for many platinum trophies: the trophy’s name also functions as a title for the player, identifying her as someone who has proven herself to truly embody some aspect of the game. For all its focus on descriptive trophies, Dark Souls is actually a very good example of this kind of platinum trophy: all of the Dark Souls games have “The Dark Soul” as the title of their respective platinum trophies, implying that the player who has earned all other trophies in the game’s world has proven herself to truly embody the Dark Soul, which, in the metaphysics of Dark Souls, constitutes the literal source of humanity in the universe.[5]

For trophy systems that adhere to this convention, the platinum trophy implies that the player is worthy of the title corresponding to the platinum trophy’s name by virtue of having completed all of the other tasks that have been related to unlockable trophies. Therefore, the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake is identified by its trophy system as being worthy of the title “Master of Fate” by virtue of having completed all of the other tasks that have been related to unlockable trophies in Final Fantasy VII Remake.

That’s pretty straightforward and unsurprising given how heavily the game leans on the theme of challenging fate. As the player defeats the Whispers, reiterates the game’s chapters to make different choices and unlock different character outfits, and plays the entire game again on a harder difficulty to push Cloud’s limits and overcome new challenges, it seems as though she’s really worthy of being called the master of fate: she overcomes obstacles that Cloud and his friends aren’t meant to overcome, and she achieves things that would only be possible by using multiple playthroughs of the game to transcend any single “fated” version of the plot.

Seen in this light, Final Fantasy VII Remake’s trophies don’t seem all that groundbreaking—in fact, for all I’ve said, the game’s platinum trophy seems like a descriptive trophy, no different than the “Defeat the Soul Lords” trophies of Dark Souls. The key to understanding how the game’s trophy system is radically interpretive actually lies in something not included in the trophy system at all: more specifically, Final Fantasy VII Remake’s trophy system commits an act of omission that redefines the scope of what the player is able to alter as a “Master of Fate.”

In Chapter 14 of the game, when Cloud, Tifa, and Barret spend the night at Elmyra’s house before setting off to Shinra HQ to rescue Aerith, Cloud wakes in the middle of the night and encounters one of three characters—Tifa, Barret, or Aerith—outside the house. The identity of the character which he encounters depends on the choices the player has made throughout the game: if she’s had Cloud make choices that favor Tifa, he’ll see Tifa; if she’s had Cloud make choices that favor Aerith, he’ll see Aerith; if she’s had Cloud make choices that don’t especially favor either of the girls, he’ll see Barret.

In a game that allows you to make choices that favor different characters and unlock different scenes with them, you might expect to have the ability to genuinely alter the relationships that characters have with one another. Indeed, in a game in which the player can be dubbed a literal “Master of Fate,” it seems like a foregone conclusion that she can mold these relationships to her will. Yet there’s no trophy even tangentially associated with the viewing of all three of these intimate scenes in Chapter 14, even though the game internally tracks how many of these scenes the player has seen.

In a game structured in the way that Final Fantasy VII Remake is, this omission demands an explanation. There’s a trophy associated with unlocking different dresses for three of the main characters, a variable in the game that is much less central to the story than variability in intimate character relationships; why, then, would the unlocking of these three scenes not at all factor into the player becoming a “Master of Fate”?

The answer to this question is simple, but it also reveals the surprising and unnerving interpretative nature of this trophy system: the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake cannot truly alter the relationships between its characters. The fact that the player’s accessing these scenes does not factor into their becoming a Master of Fate suggests that, though the player may be able to push characters beyond their limits and even literally reject the plot of the original game, the bonds between the people in this world transcend the player’s involvement.

The content of Chapter 14’s three possible “resolution scenes” (as they’re called) reinforces this perspective. Even though it seems as though the player has the option to mold Cloud’s relationships and bond more closely with a particular party member, Barret only talks about his relationships with other members of Avalanche in his resolution scene, and in Aerith’s scene, she specifically admonishes Cloud against falling in love with her, telling him that he can come and save her “if that’s what [he wants].” It’s only Tifa’s resolution scene that shows a clear, cultivated bond between Cloud and another character: as Tifa breaks down in reflection upon the destruction of Sector 7, she embraces Cloud in tears, and they share a tender moment with each other.

The player has the opportunity to view different scenes between Cloud and others, but that doesn’t imply that Cloud has established different relationships with those characters by virtue of the player’s choices—and indeed, the fact that Aerith and Barret treat Cloud with such distance suggests that Cloud’s closest relationship remains with Tifa regardless of which scene the player sees. These are characters that have transcended singular identities (in the case of Cloud and Zack), foretold apocalypses, and destined plotlines; their bonds, the game suggests, are beyond the influence of the player. Those bonds may ultimately constitute the one constant in the universe of Final Fantasy VII.

If you’re like me, you might have been confused when Final Fantasy VII Remake gave you a number of dialogue choices and similar relationship-building-choices for Cloud, only to discover that the single apparent upshot of those choices is an optional scene that’s not associated with a trophy and doesn’t imply that anything’s really changed in Cloud’s relationships. But the game’s trophy system—in particular, the conjunction of the name of its platinum trophy and the absence of a trophy for viewing the resolution scenes—plays on that confusion to give players a stark new understanding of their relationship to this game, this universe, and these characters. As the game’s story concludes, the player feels empowered, spurred onward as an agent that’s able to overcome fate itself, and the platinum trophy’s name reaffirms her self-evaluation. Yet, as she completes the task of exploring 100% of all the possibilities within this game, she finds that the bonds between these characters are the one thing that escapes the scope of her influence, despite the many hours she’s spent “controlling” the characters.[6], [7]

The player’s final act of completing her exertion of influence on the game and achieving the platinum trophy is accompanied by an unexpected demonstration of her limitations and subordination to the game’s main characters—an interpretive turn that leaves us with a new respect for the strength and immutability of their bonds. Final Fantasy VII Remake accomplishes this subversion of player perspective with only a trophy system, setting the standard for how trophies can be used as a mode of storytelling.

Toward Trophies as Intertext

Final Fantasy VII Remake has set the standard for trophies as storytelling, but there’s no reason to suppose that this is the final word in trophies’ narrative capabilities.

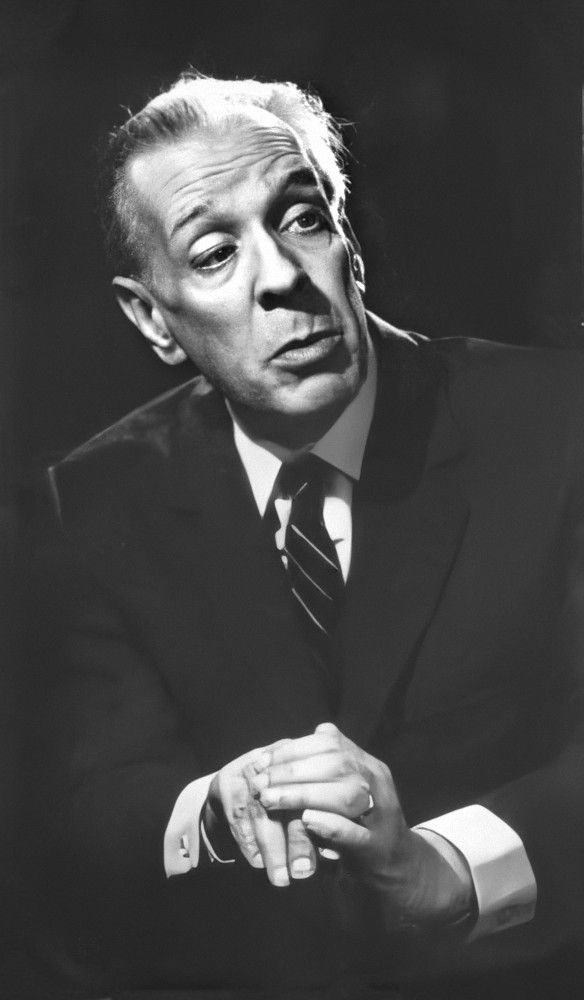

As Remake built on the innovations of games like Hollow Knight, so too could future games develop even more sophisticated systems of meaning-making through trophies. As a model, consider one of storyteller Jorge Luis Borges’ favorite short-story formats: in stories like “The Approach to Al-Mu’Tasim,” “A Survey of the Works of Herbert Quain,” and “Three Versions of Judas,” Borges takes the approach of writing a fictional review or scholarly article about an equally fictional work of body of works. For example, the “Survey of the Works of Herbert Quain” is a fictional essay surveying the fictional works of a fictional, deceased author, Herbert Quain. While these works are classic examples of experimental fiction, they also propose a compelling framework for what trophy systems could become: a form of intertext within a single work of fiction.

Jorge Luis Borges in 1967.

“Intertext” is a term that literary theorists use when two distinct texts are in dialogue with one another and thereby establish a relationship and literary commentary that spans beyond the reaches of the text itself—think, for instance, of the relationship between something like Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, and James Joyce’s magnum opus, Ulysses, which is “in conversation” with The Odyssey by virtue of both its form and content. Intertextual relationships can allow readers to contemplate ideas like the relationships between multiple authors and multiple fictional worlds, which stretches our understanding of literature beyond our typical mode of engaging with fictions. Borges helped to innovate in the literary world by bringing that same kind of intertextual exercise to a single work of fiction, allowing readers the rich and complex experience of simultaneously engaging with a fictional story and a fictional commentary on that story.

We may be witnessing the birth of this same kind of single-work intertext in the case of video-game storytelling. Much like the analytical footnotes in Borge’s fictional reviews, trophies have the potential to function as miniature injections of commentary and interpretation on the content of a video game’s story as it evolves. As we’ve seen, even something as relatively simple as the omission of a key event from a trophy system can lead players to radically reinterpret a game’s story and their place in it. Consider what could be achieved if every single trophy in a game were deliberately designed with that same kind of interpretive function in mind.

Final Fantasy VII Remake has set down the gauntlet of trophy-based storytelling. It’s up to future games—and indeed, maybe even future Final Fantasy titles—to pick it up.

- Because Final Fantasy VII Remake is currently a PS4 exclusive, I’ll be using the term “trophy” throughout the game in order to reflect PlayStation’s achievement nomenclature, but the substance of what I’m saying could be just as readily applied to achievement systems like the Xbox’s as well. The one exception is the discussion of platinum trophies, which don’t currently have an analogue on the XBox achievement system. ↑

- Peter Finn has the definitive analysis of trophy-based systems as motivational tools. ↑

- There’s an interesting and currently under-theorized question of the identity of the agent completing the actions referenced by achievement: When I, the player, earn the “Staggering Start” trophy in Final Fantasy VII Remake (awarded for “[staggering] an enemy”), is the trophy marking the occasion of the player staggering an enemy or the occasion of Cloud, the avatar, staggering an enemy? (Or, if you subscribe to my theory of player-avatar relations, you have yet a third option: Is the trophy marking the occasion of the fictional player making it the case that Cloud, the avatar, staggered an enemy?) As we develop a more robust understanding of how trophies factor into the overall ecosystem of video-game storytelling, it will be vitally important to answer this question—but, at this earlier stage in our investigation, we can set it to the side. ↑

- You might worry that the difference between descriptive and interpretive trophies is a difference in degree rather than a difference in kind because of the following argument: “Individual players have differing perspectives on video-game stories and all descriptions, no matter how apparently neutral, offer a perspective and interpretation of their referent. Even ‘Defeat Gravelord Nito’, for instance, casts a certain interpretive light on the battle with Gravelord Nito: the concept of ‘defeat’ implies a kind of competition between two competent parties—distinct from, for instance, the concept of merely killing Gravelord Nito. Therefore, descriptive trophies are really just subtler cases of interpretive trophies.” I don’t think that this argument would decisively undermine anything I have to say here, but it would make the innovations that I’m describing in trophy-based storytelling less substantively distinctive from those trophy systems that came before.

But I don’t think that this argument holds water upon closer examination. The reason lies in what Wayne C. Booth called “implied authors” and “implied readers.” The basic idea beyond these concepts is that, given any text (where a text is the complete substance of a storytelling object, like all the words of a novel or all the audiovisual content of a film), an audience member can infer a conceptual author that would have created this text in that particular way in order to espouse particular views—an implied author—regardless of whether that conceptual entity aligns with what the actual, flesh-and-blood author intended when he or she created the text.* In just the same way, audience members can infer from the form and content of the text a conceptual reader that approaches the text with certain attitudes and expectations: stories are written with certain audiences in mind and therefore play off of the expectations and assumptions that pertain to that particular audience. In the case of video-game stories, this conceptual “reader” is the particular kind of gamer that the video-game story implies will be engaging with it: a gamer with particular expectations and assumptions about the game. Because the “text” of the video-game story implies that its player will have certain expectations and assumptions, a “descriptive trophy” is technically “descriptive” exactly in the sense that it coheres with, endorses, or reflects the implied player’s expectations of the event(s) to which that trophy refers. Contrariwise, an “interpretive trophy” is technically “interpretive” exactly in the sense that it diverges from, challenges, or otherwise subverts the implied player’s expectations of the event(s) to which that trophy refers.

Therefore, the difference between descriptive trophies and interpretive trophies is a difference in kind, not a difference in degree—the key in recognizing this is just to analyze them on the level of the implied player, which has fixed attitudes and expectations with respect to a given video-game story, rather than the literal player, who is free to have whatever attitudes and expectations she pleases.

*The classic example that shows why there must be this kind of semantic construct of the implied author above and beyond the literal author of a text is a text that is just “too good” at being ironic. Imagine that I’m a Democrat trying to show how ridiculous I believe Republican values to be by writing a text that parodies that views: the text argues in favor of the most extremist Republican views possible in order to show readers how ludicrous and unworthy of endorsement such politics are. However, if the text argues too well in favor of these extremist views, people might mistakenly believe that the text was written by someone who seriously endorsed those views. In that case, we observe a clear distinction between the text’s literal author, a Democrat, and the text’s implied author, a Republican extremist that readers would infer wrote the text. Such an implied author always conceptually exists in texts—the attitudes and intentions of these conceptual entities just align better or worse with those of the literal author depending on the text in question. ↑ - There are many other games with platinum trophies that follow this formula and make it appropriate to call this formatting of the platinum trophy a convention. Here are just a few more from recent additions to my own gaming library: “Director of the FBC [Federal Bureau of Control]” in Control; “The World Wanderer” in Final Fantasy XV; “Professor of Arkham University” in Call of Cthulhu; “Revenant Preeminent” in Code Vein. I encourage you to consult your own library and see how many games you’ve played adhere to this convention. ↑

- “Controlling,” in scare quotes, because I don’t subscribe to the view that players of video games actually control the characters in the video game in the way that gamers and analysts typically suppose. I articulate my preferred theory here. ↑

- Notice that this kind of narrative effect is only possible because of the gap that exists between “completing the game” in the sense of earning all the game’s trophies and “completing the game” in the sense of doing everything possible in the game, including those things that aren’t represented by trophies. Some in trophy-hunting communities complain that this gap undermines the value of a platinum trophy (because the trophy doesn’t accurately represent “doing everything” in the game), but this distinction, like so many other formal distinctions in storytelling media, is exactly the kind of thing that allows for further innovation in storytelling to happen. Thanks to Dan Hughes for this observation. ↑

Continue Reading

- The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake series navigation: < “How Final Fantasy VII Remake’s Whispers Changed Fate—and Storytelling″ | “Apocalypse Soon? Final Fantasy VII Remake as Apocalyptic Literature” >

4 Comments

Allomancer · May 16, 2020 at 2:26 am

Very good analysis, but why do you think that Aerith treat Cloud with distance? She’s flirting with him for all the game, and even in the dream she’s warm with him. I think she’s telling him to leave her to the Shinra Building becouse she thinks she belong there. Or maybe, it’s because she feels the tragedy.

“such distance suggests that Cloud’s closest relationship remains with Tifa regardless of which scene the player sees”

I think this go against the concept of love triangle, pushing the player into a “canon” or “official” relationship: to me, this is the opposite of the will of the authors.

Aaron Suduiko · May 18, 2020 at 2:19 pm

Hey, Allomancer! Thanks so much for reading, and I’m glad you enjoyed the article. I hope you get the chance to check out the other articles in the series, along with our analyses of other games!

You raise a fair point. By way of an answer, let me offer an alternative way of looking at the puzzle you’re talking about that aligns with my commentary in the article.

Instead of seeing Cloud’s relationships with Tifa and Aerith as a love triangle that the player should be able to control and yet is unable to control, consider the idea that Aerith may just be a generally friendly, loving, and open person. We witness her being generous of spirit with many different people throughout the game, and it may be the case that she’s just being outgoing and friendly toward Cloud, too—maybe she simply recognizes how walled off he is and wants to help him open up.

(Another possible explanation, which I’ll be vague about in order to avoid unnecessary spoilers, is that Cloud reminds Aerith of her first love. That could also explain why she seems to experience, as you say, “warmness” toward Cloud despite not wanting to actually be with him, romantically speaking.)

If we go along with this interpretation, it might be that Cloud was never really in a love triangle: the player just believed that he was. We see dialogue options and two main female characters, and we’re primed to expect the opportunity to choose between them. That would end up reinforcing the analysis I’ve offered of the trophy system: even though we expect to be able to influence these relationships, they’re ultimately outside the player’s realm of influence.

Thanks again for checking out my work! Hope you keep in touch.

Amir · April 30, 2022 at 7:44 pm

Wait, you also did the last two chapters on Hard first? and then came back to finish the previous ones?

I did that to test myself; to see if I can beat those chapters on Hard which seemed hardest and longest to me.

Also, while you’ve talked about the narrative aspects of how trophies have affected the experience, I want to add that in terms of the gameplay experience, the trophies were also very transformative. Hard Mode requires the player to devise completely new ways for defeating the same foes.

Beating the game on Hard Mode was surprisingly so much more fun than the Normal difficulty. Trying to exploit enemy weaknesses while managing MP made each fight very engaging. On the other hand, boss fights were another kind of beast which required using specific builds. Coming up with the builds and developing Materia also proved to me that this game is as deep, if not more, as the original game.

Thanks for the read. Actually thanks for every Final Fantasy article you guys have done.

Aaron Suduiko · May 2, 2022 at 4:42 pm

Hey, Amir! Thanks so much for reading, and I’m so happy that you’ve found our readings of Final Fantasy valuable; between you and me, they’re some of my personal favorites!

I actually don’t think, to the best of my recollection, that I started Hard Mode with the last two chapters, although that fascinating choice speaks well of you as the kind of player I have in mind in this article and my overall reading of the game: one who wants to step beyond the confines of traditional storytelling to see how far he can push himself as a player and the characters as intrinsically valuable entities.

You make a great point about the gameplay sophistication of Hard Mode. My own two cents here are that that sophistication is intimately related to how the game gets its players to think more deeply about its story: as you devise new strategies and perspectives on the actual mode of making process through the game, you’re naturally invited to similarly cultivate new lenses for viewing the story in entirely different dimensions.

Thanks again for reading! I hope that you keep in touch and get the opportunity to check out some of our other work as well.