The following is an entry in The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake, a series that analyzes how and why the remake of Final Fantasy VII is a landmark innovation in both Final Fantasy and video-game storytelling more broadly. Read the series’ mission statement here.

Since Final Fantasy X, the franchise’s storyteller’s have traded in tales about killing gods for tales about rewriting stories. With Final Fantasy VII Remake, they’ve revealed how to turn that storytelling formula into something players actually care about.[1]

(A friendly warning: spoilers are ahead for Final Fantasy VI, VII, X, XIII, XIII-2, XV, and VII Remake.)

At the climax of FFX, Auron famously proclaims to his comrades and the player, “Now! This is it! Now is the time to choose! Die and be free of pain, or live and fight your sorrow! Now is the time to shape your stories! Your fate is in your hands!” At the turning point of FFXV, Bahamut places the destined hero, Noctis, into stasis in order to give him time to reflect and come to terms with the destined conclusion of his story: self-sacrifice for the sake of the world. At the midway point in the Final Fantasy XIII trilogy, the player is tasked with resolving paradoxes in the story’s timeline in order to get events back on track and reconstitute the main protagonist.

Auron’s iconic speech at the end of Final Fantasy X has been synonymous with the credo of shaping one’s story in the way that only the player of a video game can.

No doubt, there are still gods to kill in these more recent Final Fantasy worlds, but the focus has increasingly been on the explicit relationship between the characters of these worlds coming to terms with the stories in which they’re either willingly or unwillingly playing a role. One compelling explanation for this shift in focus, I think, is that the Final Fantasy mode of storytelling is moving more towards the concept of what I’ll call relatability: the capacity of a story to inspire direct connections between its events and the events of its audience’s lives.

In this article, I want to convince you that Final Fantasy VII Remake is remarkable because it found a way to tell a relatable story about changing fate, succeeding where many other stories—including video games—failed. We’ll start by exploring why relatability is something we would value in stories at all; then, we’ll see why it’s really hard to tell a relatable story about the theme of challenging fate, even though this is one of the themes we’d most want to relate to. We’ll consider how previous Final Fantasy titles tried and failed to overcome this challenge using the concept of player interactivity, which will ultimately allow us to discover how the deft use of Whispers in Final Fantasy VII Remake tricks the player into bringing about a uniquely relatable story about changing fate—much to the player’s horror.

The Value of a Relatable Story

For the purposes of our analysis, a story is relatable to the extent that it is capable of inspiring direct connections between its events and the events of its audience’s lives.

To be sure, stories don’t need to be relatable in this technical sense to be compelling or worthwhile. There are many abstract concepts that stories can only allow us to contemplate through very unrelatable scenarios—like the entirety of Plato’s worldview, for example. This kind of metaphysical abstraction has little grounding in real-world events in the first place, and so there’s no need to try to represent it to audience members in a relatable way—indeed, to do so could be a fool’s errand.

Try architecting a relatable story about Plato’s complete metaphysics. Xenoblade Chronicles 2 is a masterpiece of storytelling, but “relatable” it is not.

But you might think that some concepts are better conveyed to audience members through relatable stories rather than unrelatable stories. In particular, if a story is trying to convey some message about an emotionally charged aspect of human experience, it’s reasonable to suppose that it will be more successful if it conveys that message in a way that naturally invites audience members to connect their real and relevant human experience to those human experiences represented in the fictional story, accessing whatever real emotions they felt about their pertinent real experiences.

To take a very contrived example, suppose that I’m trying to tell a story that conveys to its audience the message that theft is emotionally harmful. Here are two candidate scenarios that I could use to try to convey that message:

- Our protagonist has a memento from his deceased mother inexplicably stolen; the thief is never identified, the protagonist’s sense of self-worth unravels, and she gradually descends into a depressed madness.

- Our protagonist’s world contains a secret crystal that connects it to a parallel world; when a malicious interdimensional entity steals the crystal, the protagonist’s world begins to wither and die from being thrown out of balance.

Both of these scenarios could be fleshed out in various ways to become compelling, valuable stories on their own terms; however, all else being equal, the first of these two scenarios stands a better chance of conveying to its audience the message that theft is emotionally harmful. That’s grounded in the fact that Scenario 1 is more relatable than Scenario 2: an audience member can better connect events in their own lives (perhaps a time they inexplicably lost something with sentimental value and suspected that it had been stolen) with the events of Scenario 1 than they can with the more metaphysically inventive events of Scenario 2.[2] When an audience member is able to connect events in her own life with the events of a story, she is better able to access an emotion-laden message about those events (a message such as ‘theft is emotionally harmful’) by accessing the emotions that she felt or feels towards the events that really happened to her.

Put another way: when a story’s out to get something emotionally charged across to its audience, it can do it better through events with which the audience can easily sympathize.

Changing Fate: Relatable, Yet Unrelatable

In storytelling, the theme of challenging fate—recognizing the expected outcome of one’s life and struggling to change that outcome—presents a unique dilemma in relation to relatability—and it’s this dilemma that Final Fantasy VII Remake has resolved.

Here’s how the dilemma comes about: on the one hand, the idea of being doomed to some fate that we want to defy is one of the most deeply human ideas. We feel as if we’re meant to be someone other than the person who we are; we feel as if we can see the trajectory of our future lives, and we struggle to change that trajectory. The ancient Greeks’ staggeringly sophisticated obsession with fate is the clearest proof of how deeply this theme is imprinted on our DNA.

The Greek tragedy of Oedipus Rex—a scene of which has been illustrated above by Francois Xavier Fabre—is one of the oldest and most widely known stories about a man struggling against fate.

On the other hand, though, it’s really hard to tell a story that relatably confronts the theme of challenging fate. The reason why, I think, is that it’s hard for us to believe that characters in relatable stories can really defy fate. If I see a film where a boy is being set up by his parents to become a basketball star and that boy ultimately breaks away from their expectations to become a scientist, my first response isn’t, “Oh, that boy challenged his fate”: my first response is, “Oh, that boy was able to overcome the odds in order to do what he was always meant to do.”

The challenge for storytellers here is that their stories, by definition, feature characters that progress through a predetermined series of events—namely, the series of events architected by the author. To make matters worse, since most stories aim for a satisfying sense of closure at their end (the feeling on the part of the audience that all the story’s events have resolved in the only way they possibly could have resolved), many audience members will feel that the outcome of a character’s plot in a successful story was the only outcome possible for that character. So, in many run-of-the-mill stories about relatable characters trying to change their lot in life, many audience members walk away with the sense that the character was meant to try to change its lot in life—after all, that’s the way its literal author designed the course of its story.

With that challenge in view, the natural strategy for many storytellers is to introduce some fantastical element—what I called a “metaphysically inventive” element in the last section’s thought experiment—into their story to make it clear within the ecosystem of the fiction they’ve created that a character is recognizing and resisting their preordained destiny.

- Ancient Greek storytellers did this by manifesting the concept of Fate itself, which characters usually end up failing to avoid.

- More recent avant-garde storytellers like Luigi Pirandello did this by telling stories about literal, self-aware characters that try to enact or revise their own stories.

- Many video-game storytellers—especially those behind JRPGs—did this by introducing gods or god-like entities that threaten the universe and therefore must be defeated by the story’s protagonist(s).

Final Fantasy VI’s court-jester-turned-nihilistic god, Kefka, is a classic example of a JRPG antagonist-god whose intended fate for the universe must be overturned by the story’s heroes.

These solutions have given birth to some of the most innovative and compelling stories of all time, but they throw relatability out the window by introducing metaphysical entities that exist outside the story’s audience’s realm of real experience. And so we arrive at what, in true JRPG fashion, I’ll call the dilemma of fate: for any given story about a character recognizing and challenging its fate, either that story is relatable and therefore fails to represent the character recognizing and challenging its fate, or that story represents its character recognizing and challenging its fate and is therefore not relatable.

The dilemma of fate might not seem like a big problem, but remember that the idea of challenging fate is deeply human and oftentimes very emotional when we meditate on it in our own lives—so it’s just the kind of theme that you’d hope master storytellers would spin tales about in a relatable way. Yet, unless we can find a way to escape the dilemma, that’s not possible.

As it happens with so many storytelling problems we encounter on With a Terrible Fate, video-game storytelling held the solution—but it wasn’t in the first place you’d think to look.

The Red Herring of Interactive Storytelling

Intentionally or unintentionally, it seems like the Final Fantasy franchise has quietly been trying to solve the dilemma of fate since 2001, only to discover that this dilemma could uniquely be diffused by a remake of the kind they just released. But to understand why that remake’s solution to the dilemma is a very natural one rather than something coming totally out of left field, we need to understand the previous attempt in video-game storytelling to diffuse the dilemma: making player interactivity an act of challenging fate.

As I highlighted at the start of the article, many of Final Fantasy’s flagship titles since X have concerned themselves with the question of what it is to write or rewrite a story. This focus has given rise to some of the highest regarded JRPGs in all time, most especially Final Fantasy X itself. The iconic opening line of X, I think, encapsulates why this focus may seem, at first glance, like a promising way to overcome the dilemma of fate:

“Listen to my story.”

Tidus at the outset of Final Fantasy X, marking the beginning of its story.

This line, which Tidus speaks to the player before the saga unfolds itself, is laden with irony precisely because it’s the opening line of a video game.[3] The player cannot simply sit back and listen passively to Tidus’ story: to borrow from Auron’s speech at the game’s climax, the story of the game is something that the player must “shape” by making decisions and actively guiding the protagonists on their way. By taking an active role in the creation of the game’s story, one might think, the player becomes more directly sympathetic to the actions of the protagonist and is therefore able to feel as though they really have changed fate along with Tidus and his friends when they stop the cycle of death, rebirth, and Sin that has plagued Spira for generations.

But alas: as is the case with most JRPG stories, things aren’t that easy.

While it’s all well and good to tell video-game stories about the nature of characters’ roles in a story, the structure of video games is actually more conducive to making players feel unable to challenge fate rather than better able to challenge it. That’s because the issue of authors architecting plots that tend towards closure, which we discussed in the previous section, hasn’t gone away in video games: it’s just hidden itself behind the curtain of interactivity.

In a game like Final Fantasy X, the player doesn’t have any say in designing the universe of possible events for Tidus and the gang—that’s the task of the game designers. It’s true that Tidus & co. wouldn’t reach the conclusion of challenging fate and “shaping their own story” without the input of the player, but all of that happens within the bounds of the narrative set out by the game’s designers. Therefore, even if it initially seems like player participation in the rewriting of a game’s story à la Final Fantasy X seems like a way out of the dilemma of fate, it really just puts us right back on the “relatable but not challenging fate” half of the dilemma.

On a certain interpretation, the narrative of Final Fantasy XIII-2 almost mocks the player for thinking that this kind of storytelling ever stood a chance of getting them out of this dilemma.[4] Its story purports to give the player the freedom to travel through alternate timelines and view a diversity of potential outcomes to the story, yet all of this “freedom” is directly in service of removing aberrations from the timeline in order to get the story back on its proper course—an irony that’s not lost on Caius Ballad, one of the most tragically sympathetic villains I’ve ever encountered, who literally wants to kill the goddess of time in order to prevent the player’s characters from making countless edits to the timeline and consequently killing his beloved seeress companion whose life shortens every time the future changes. The game practically screams at the player, on this reading, that to try to join with a game’s protagonists in challenging fate is to play right into the ultimate fate that the storytellers had in mind all along.

The dilemma of fate seemed to be standing strong, forcing even us gamers with sophisticated new forms of storytelling to choose between relatability and challenging fate. But Final Fantasy VII Remake found a way out of the dilemma—and all it took was a Whisper.

Final Fantasy VII Remake, Whispers, and the Trap of Undoing Your Own Expectations

The Whispers of Final Fantasy VII Remake resolved the dilemma of fate by tricking the player into challenging a fate of her own design.[5]

I want to begin explaining what that means by highlighting what I’ll recall for years as the moment that’s brought me the most terror I’ve ever experienced while playing a Final Fantasy game. I don’t mean ‘terror’ in the sense of a horror game that makes you anxious about something around a corner or even frightens you on a cosmic level: I mean the kind of awestruck terror you experience when the ground falls out from underneath you at the peak of a roller coaster’s first hill and you feel totally powerless, adrift.

After Cloud, Tifa, Barret, Aerith, and Red XIII challenge the arbiters of fate (we’ll return to them in a moment) and subsequently face off against Sephiroth, Cloud finds himself transported to “the edge of creation” with Sephiroth. As Cloud gets his bearings, Sephiroth takes Cloud’s hands, smiles, and quietly warns him:

“Careful now. That which lies ahead… does not yet exist.”

Sephiroth’s admonition induces terror because of how deftly it melds the realities of the fiction with the reality of the player, leaving the player totally adrift. At that moment, Cloud and Sephiroth are at the edge of their native universe and their future really is unclear because Cloud and his friends have defeated the Whispers that were safeguarding the “fated” future. But, of course, at this moment at the end of Final Fantasy VII Remake, Cloud and Sephiroth are also at the “edge of creation” in terms of being at the outer limits of the literal video game that was created—and, at this terrifying moment in the real history of gaming, that which lies ahead—the game that will presumably pick up where Final Fantasy VII Remake left off—does not yet exist.

On its own, this is an interesting but fairly trite observation. What makes this terrifying melding of fiction and reality so groundbreaking and salient is the relationship into which the player has fallen with the Whispers, much as one falls into the cleverest of traps. To understand how that relationship comes to fruition, we have to understand how the trap is set in the first place.

The Whispers functioning as a wall to impede Cloud and Tifa’s progress in the Sector 7 slums.

Initially, the “Whispers” function as an unusual way of turning the “invisible rails” of game design—things like the narratively inexplicable “invisible walls” that keep avatars bound within certain areas when noncompliant players try to move them outside the area of the current mission—into narratively relevant entities. In one of Cloud’s earliest encounters with them, the Whispers constitute this kind of wall in order to block him and Tifa from proceeding down a particular path in the Sector 7 slums. Much like invisible walls, and much like the name “Whisper” suggests, “you can’t even see them unless you make physical contact first” (Cloud’s words), further supporting their role as unseen guidance that only manifests if one attempts to go outside the intended narrative trajectory.

As the story nears its conclusion in Shinra HQ, however, the Whispers take on a much more active role—reviving Barret, for instance, after Sephiroth skewers him. Red XIII, who identified the Whispers as “arbiters of fate” in a recitation of knowledge he gained after Aerith touched him, explains to Barret that this intervention of the Whispers means “this death was not the one ordained for [him] by fate.”

With the help of a Whisper, Barret escapes his “erroneous” execution by Sephiroth.

Ultimately, once Cloud & co. escape Shinra HQ, they’re confronted by yet another wall of Whispers embedded with a portal, beyond which Sephiroth waits for Cloud. Aerith explains at this juncture that these agents of fate, the Whispers, are agents that can be defeated—and that, by defeating them, the gang can change fate and save the Planet from Sephiroth.

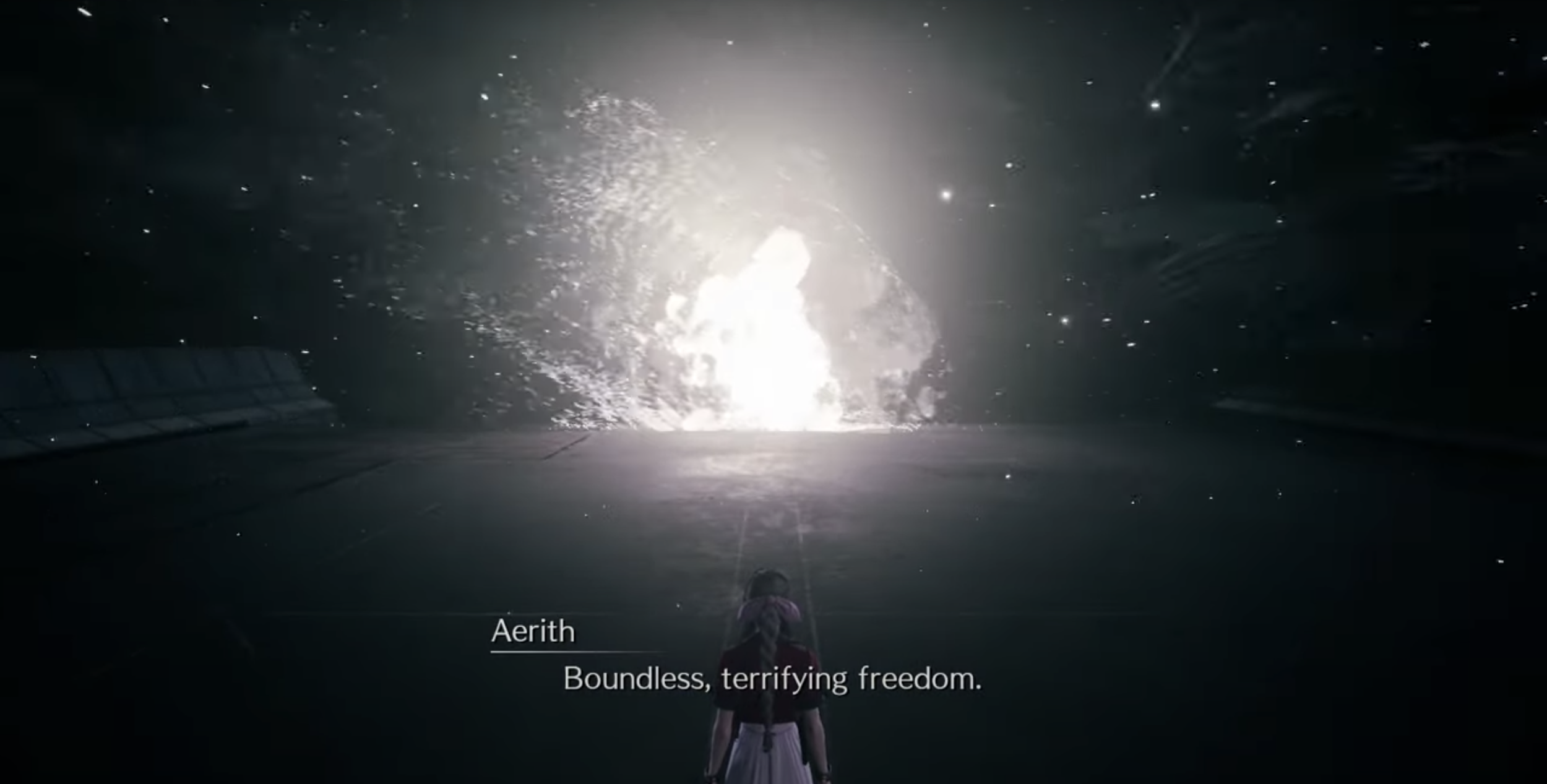

Aerith warns Cloud and the gang of what will happen if they really do manage to change fate.

So far, so status quo: for all I’ve said, we’ve got a literal manifestation of destiny that will allow Cloud and his friends to challenge fate at the cost of relatability. We’ve gone no apparent distance toward resolving the dilemma of fate.

The key is what happens once Cloud steps through the portal and the true nature of the Whispers is revealed.

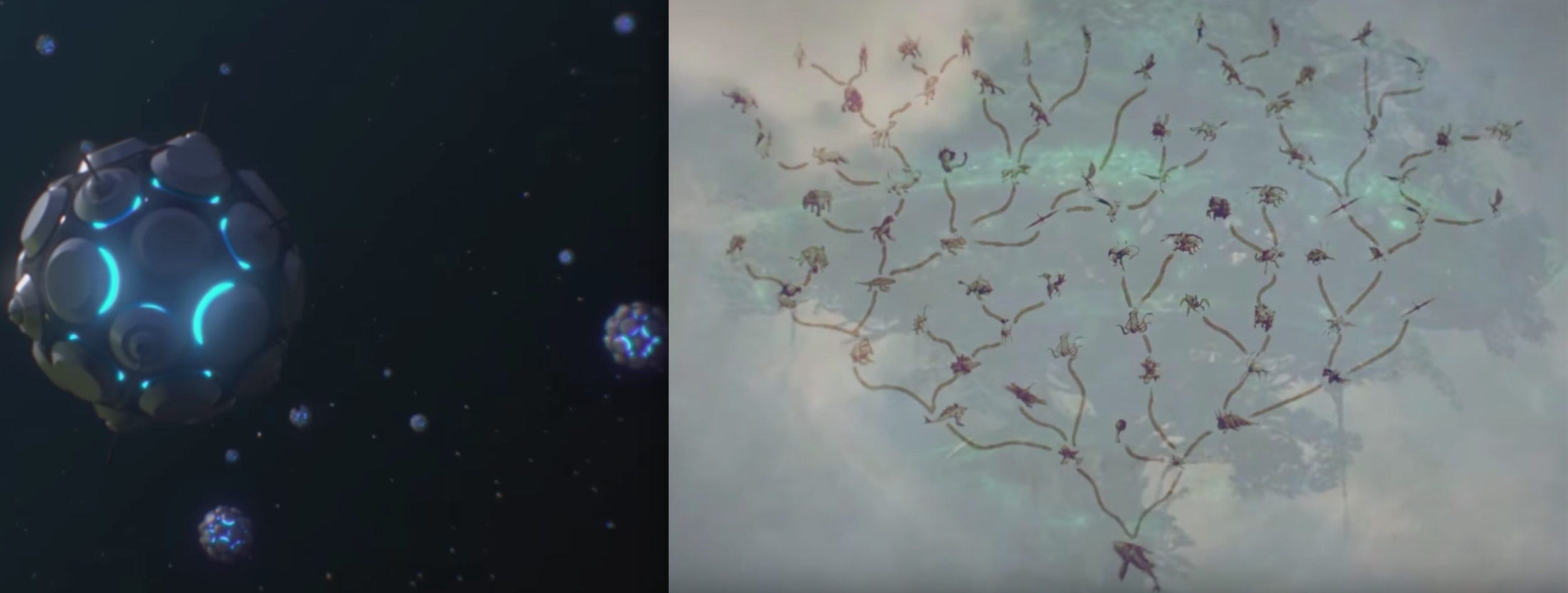

Midground, left to right: Whisper Viridi, Whisper Rubrum, and Whisper Croceo. Background: Whisper Harbinger.

When Cloud and his party step through the portal to chase after Sephiroth, they enter a kind of crumbling metaphysical realm in which they’re confronted by four Whisper amalgams: Whisper Viridi, Whisper Rubrum, Whisper Croceo (above: midground, left to right), and Whisper Harbinger (above: background). The enemy descriptions provided by using the “assess” skill on them informs us that these Whispers are no longer merely guiding the world towards a certain future: they are actively battling the party in order to ensure that future comes about. Viridi, Rubrum, and Croceo are described as “[entities] from a future timeline that [have] manifested in the present day,” fighting with their respective weapons “to protect the future that gave shape to [them]. Whisper Harbinger’s description, meanwhile, provides more color to the nature of Whispers as a collective:

“An accretion of Whispers, the so-called arbiters of fate. The creatures appear when someone tries to alter destiny’s course. They are connected to all the threads of time and space that shape the planet’s fate.”

In order to reach Sephiroth, Cloud and his friends must defeat Whisper Harbinger, the supermassive Whisper amalgam that seems to preside over this metaphysical realm, but they can’t reach him directly: instead, they must defeat Whispers Viridi, Rubrum, and Croceo in order to wound Whisper Harbinger vicariously; he falls once his three “champions” are finally defeated once and for all.

As Cloud and the team gain ground against the Whispers throughout the battle, they periodically see visions that the player will recognize as events from later on in the narrative of Final Fantasy VII; the first these visions is actually the very last scene in the original game, when Red XIII takes his progeny to see the ruins of Midgar years after the dust has settled from the game’s events. When Barret asks what this vision is, Red XIII—presumably again channeling the knowledge that Aerith imparted to him—identifies it as “a glimpse of tomorrow if we fail here today.”

Red XIII identifies visions from the future of the original Final Fantasy VII as visions of failure.

Red XIII’s analysis here is the turning point for understanding how this conflict between Cloud’s party and the Whispers overcomes the dilemma of fate—not to mention why Sephiroth’s observation that “that which lies ahead does not yet exist” evokes so much terror in the player. A player of Final Fantasy VII Remake who has played the original Final Fantasy VII recognizes that the future from which these Whispers hail—the future they’re fighting against Cloud and his friends in order to protect—is the future that the player herself brought about when she played Final Fantasy VII. Suddenly, the outcome that the player expected from the remake based on her experience of the original isn’t just no longer evitable: it’s also directly identified as the ending of failure, that which the player and her avatars are fighting to avoid in the remake.

Not only are the player’s expectations of the plot of Final Fantasy VII Remake challenged by the remake’s endgame: when the trap of the Whispers is sprung, it seems an awful lot like the player is actually being made to fight against herself and what her expectations for the game were. Here’s what I mean by that:

A decent amount of discussion amongst Remake fans has already been dedicated to speculation about the identities of Whispers Viridi, Rubrum, and Croceo—and indeed, their variety of combat styles, corresponding to those of various characters from across the series, naturally invites that kind of speculation. However, I’m personally more interested in contemplating the nature and identity of Whisper Harbinger. That immense, unreachable entity that presides over the battle, so enigmatic (another word used to describe the Whispers) that it almost seems beyond the ken of Cloud and his friends. That accretion of the spatiotemporal threads that shape the thread of the Planet, unable to speak directly with the Planet’s inhabitants yet pulling the strings that determine their overall trajectory. That agent who only does battle and can only be fought by proxy through the medium of his party of three warriors, whom he appears to control in some non-specified way.

Doesn’t Whisper Harbinger seem quite a bit like you, the player of Final Fantasy VII?

Like Whisper Harbinger, the player of a video game presides over its world while (in most cases, and certainly in the case of Final Fantasy VII) remaining unreachable, beyond the ken of its inhabitants. Like Whisper Harbinger, the player of a video game guides its world’s trajectory from a distance. Like Whisper Harbinger, the player of a video game only does battle and can be fought by proxy through the medium of an avatar or a party, whom she appears to control in some non-specified way.[6] And, like Whisper Harbinger, the player of Final Fantasy VII has a stake in Cloud and Midgar’s story going a certain way: namely, we expect it to conform to the narrative of Final Fantasy VII since we played that game, brought its outcomes about, and saw that, within the universe of that game, things couldn’t have turned out any other way (i.e. there were no “multiple endings” for us to access, altering the fate of the world).

So, in the epic climax of a story that we thought we knew very well, the Whispers that we once thought to merely be interesting narrative manifestations of a game’s “invisible rails” are revealed to be perfect metaphors for our own expectations of and stake in the way the story went the first time: without consciously reflecting on it before our confrontation with Whisper Harbinger, that version of ourselves that played and knew Final Fantasy VII was guiding us along the expected path of the game’s story. Then, upon this final confrontation, the game challenges us to metaphorically defeat those expectations and create a Final Fantasy VII world in which things could be otherwise than they were in the original game.[7]

This challenge for the player to defeat her own expectations is an exceedingly clever way of dissolving the dilemma of fate. Remember, the dilemma told us that a story about challenging fate would either (1) be relatable but not actually manage to represent the theme of challenging fate (because the audience would still feel that events were “meant to turn out” the way they did in the narrative) or (2) represent the theme of challenging fate but not be relatable (because the accurate representation of challenging fate would introduce “metaphysically inventive” concepts too far beyond the pale of the audience’s experience). Final Fantasy VII Remake has managed to tell a relatable story about challenging fate by making the player’s own experiences the content of the “metaphysically inventive” concept it introduced in order to represent the theme of challenging fate.

Merely fighting against abstract entities that protect fate is a deeply unrelatable conceit (the final battle in XIII-2, against three incarnations of Bahamut in an abstract space, comes to mind), but Final Fantasy VII Remake made its abstract guardian of fate a player-analogous agent that is protecting experiences that the player actually had: namely, the experiences of the original Final Fantasy VII. The player can find both credibility and relatability in this challenge to fate because she herself was responsible for enacting the narrative of Final Fantasy VII the first time around; now, the remake is explicitly challenging her to imagine that that narrative could have been different—and, in fact, by having her defeat the version of herself that effected the original narrative, it’s telling her that the narrative will be different.

“Boundless, Terrifying Freedom”

This analysis of the Whisper Harbinger and the unique way in which Final Fantasy VII Remake tricks the player into abnegating her own expectations of the future plot are the reasons that there is so much terror behind Sephiroth’s claim that “that which lies ahead does not yet exist.” With the plot the player knew—the plot that she enacted in the original game—explicitly challenged and done away with, it’s not simply that the remake’s story is “To Be Continued,” nor is it simply that the next game literally hasn’t been created yet: in a very real, narratively meaningful way, the player does not know what will happen in the follow-up to the remake, despite the fact that the remake itself was predicated on the idea of reiterating the story of Final Fantasy VII.

That leaves the player feeling truly adrift, as Cloud does on the edge of creation. It creates a distinctive kind of suspense that one rarely sees in any mode of storytelling: the suspense that comes from knowing what story was expected to be told and suddenly discovering that virtually any story except the expected story is going to be told.

This is what Aerith is talking about, I think, when she warns the party that “boundless, terrifying freedom” lies on the other side of the portal to the Whispers and Sephiroth. It’s a satisfying yet terrifying instance of content mirroring form: in the original Final Fantasy VII, Cloud and the gang’s departure from Midgar marks the moment when the world opens up to them and they have more freedom in their adventure; now, as the party walks away from Midgar, they’re walking away from the one story that the player expected to be told. What remains is boundless, terrifying freedom: the freedom to imagine that things could have been otherwise.

Final Fantasy VII is an especially terrifying story for which to do this kind of imagining because of the key moments in the story that seemed—and, up until now, really were—totally unavoidable for better or worse. What if Sephiroth hadn’t cast Meteor? What if Sephiroth hadn’t killed Aerith? Without the concept of inevitable, unavoidable events as anchors for the story, the player truly doesn’t know what to expect. As Aerith and Sephiroth, both of whom seem to be aware of the fated plot and the potential to change it in Remake, demonstrate, diversions from the original story could make things much better or much worse: maybe Sephiroth could be stopped earlier, and maybe even Aerith could be saved—or, maybe Holy would never be freed to mitigate Meteor at all. Maybe Holy would never even be cast.

Presumably, the follow-up to Final Fantasy VII Remake will resolve some of these myriad questions—but that makes this current moment for contemplating and appreciating Remake on its own terms even better. There’s something narratively unusual and distinctly compelling about the story of what happens when someone who brought about a certain fate is unwittingly led by the very characters whose lives she changed to erase that fate in favor of radical freedom. One regard in which I think this remake will stand the test of time on its own terms is the way in which it lays bare our expectations for the retelling of a story and forces us to think critically about why we had those expectations. Were you disappointed when you were forced in Remake to disavow the plot you brought about in the original Final Fantasy VII? If so, why? Were you really looking forward to the death of Aerith and Meteorfall—or, had you unwittingly prioritized the value of your own actions as a callous arbiter of fate over the actual wellbeing of the characters whose fate you determined?

I don’t have the answers to these questions, and they’re pressing issues that I myself am wrestling with. But the fact that Final Fantasy VII Remake developed such a novel and relatable way for us to ask ourselves these questions as active participants in video-game storytelling is remarkable, and I think we’ll see many gamers and video games themselves striving to find the answers in the years to come.

In the meanwhile, adrift with this boundless, terrifying freedom we may have never wanted, we have reason to deeply empathize with Aerith’s final reflection as she looks back on the finite world of Midgar, knowing that the story from here on out can go any way except the way we expected:

“I miss it. The steel sky.”

- Spoiler warnings are in effect for Final Fantasy VI, Final Fantasy VII, Final Fantasy X, Final Fantasy XIII, Final Fantasy XIII-2, Final Fantasy XV, Final Fantasy VII Remake, and Xenoblade Chronicles 2. ↑

- It should go without saying that I love metaphysically inventive stories: I’ve spent years analyzing games like Majora’s Mask, Nier, and Xenoblade Chronicles, all of which are some of my favorite stories and all of which are very “metaphysically inventive.” But no one mode of storytelling can do it all, and these kinds of video games—in particular, the sort of Platonist JRPG of the form I analyzed at the very end of my work on Xenoblade Chronicles 2—simply don’t have a structure conducive to relatability. ↑

- Of course there are many other reasons on account of which this opening line is rich with meaning—as is the case with any deft opening line to any coherent story. The act of “listening” to a Final Fantasy story was novel in Final Fantasy X, the first Final Fantasy title with voice acting; many also consider the line to be misleading since the story of Final Fantasy X may be argued to ultimately “belong” more to Yuna than to Tidus. This is just the tip of the iceberg, but it’s an iceberg that’s beside the point in this article. ↑

- I’m almost certain that this was not intentional on the part of the creators: this reading is meant as a critique of how the narrative unwittingly undermined the destiny-defying theme it was trying to espouse. ↑

- In this analysis, I’m assuming that the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake antecedently played Final Fantasy VII. There’s a pressing and interesting question of how the value and narrative experience of Remake differs for the player who never played Final Fantasy VII, but it’s a question for another time. ↑

- Though, I’ve personally specified the mechanics of this apparent control that players have over avatars in some depth using my own preferred theory elsewhere. ↑

- A couple of parentheticals are worth noting here.First, as I’m implying with my use of “metaphor” verbiage, I’m not claiming that the literal, flesh-and-blood game developers decided to literally make Whisper Harbinger represent the player of Final Fantasy VII. I virtually never do analysis of that form: I’m interested in the interpretations of video-game stories that best allow for a coherent understanding of those stories, regardless of whether game developers literally recognized and aimed to actualize those interpretations. To that end, I believe that this interpretation of Whisper Harbinger as the player of Final Fantasy VII is conducive to an understanding of how the game casts its challenge against fate as a challenge that the player must level against herself and her own expectations based on the experiences she’s already had in the original version of this world.In a similar vein, I’m not taking a stand on the “identities” of Harbingers Viridi, Rubrum, and Croceo because I don’t think we have enough information to make that determination and I think their exact identities are beside the thematic point I’m analyzing in this article. To illustrate, here are two (probably) mutually incompatible possibilities for their identities that thematically cohere with my analysis of Whisper Harbinger as a manifestation of the player of FInal Fantasy VII: they could be avatars / party members that the player of Final Fantasy VII controlled in order to bring about the outcome of that original game (e.g., Tifa, Cloud, and Barret, respectively); or, they could be the player’s will made manifest in physical form—not anyone in particular, but rather puppet-like manifestations of the player’s agency over the “threads of time and space that shape the planet’s fate.” ↑

Continue Reading

- The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake series navigation: < “What’s in an Opening? A Tale of Two Title Scenes″ | “The Language of Trophies in Final Fantasy VII Remake” >

5 Comments

Scott Sheppard · May 12, 2020 at 6:03 pm

Gash dang it Aaron! I’ve been a fan of everything you’ve ever written, but this one was extremely on point. I haven’t played the remake, and to be honest am only middlingly interested in doing so, but played the original to death. So it’s a testament to your well articulated thoughts that I felt the terror of the unknown just by reading this article.

Your unique perspective – that the player is just as important to the storytelling as the plot itself – is one that I have yet been able to see workout your guidance. But that guidance has made some of my favorite games far deeper than I ever could make them myself.

Aaron Suduiko · May 13, 2020 at 11:44 pm

Oh, you—your kind words are more than I deserve!

I’m so glad you enjoyed the article, man. If nothing else, then I hope this little article series of ours can nudge you toward more than “middling interest” in playing Remake! I’d love to hear what you think of it. For my part, there’s more than one reason why I felt compelled to start writing again the moment I put it down.

Cheers to you and yours, Scott. Hope you’re staying well in these crazy times.

Miguel Garcia · May 15, 2020 at 5:14 pm

Greetings! I stumbled unto your site after it popped up in my suggestions while scrolling through my Google feed late last night. Am I glad I clicked on the link! I’ve read the “Tale of two openings” piece, listened to the Podcast episode and just finished absorbing this magnificent, thought provoking piece of writing within the past couple of hours, it’s proven to be the panacea I’ve desperately been needing. Ever since completing FF7 Remake a little over two weeks ago, I’ve been scouring the Internet and voraciously devouring any and all articles, videos, podcast, and roundtable discussions related to this game. My head has been swimming with thoughts and theories about its themes and the implications of those final closing moments. It’s truly been an emotionally charged couple of weeks since release, with fans like myself and newcomers seemingly falling into several categories, with emotions ranging from anger, disbelief, and confusion to excitement, intrigue, and elation with the way things shook out for Cloud & Co. I’m firmly in the intrigued and excited camp when it comes to the undoubtedly bold narrative decisions the mad scribes over at Square Enix decided to go with for Remake, it couldn’t have been an easy decision but they opted to step through the portal of uncertainty and I think that’s just gravy! FF7 Remake would not have sparked the kind of impassioned discussions and thought-tickling deep-dive examinations on the effectiveness of the mediums capacity to convey metaphysical narrative themes in a way that feels relatable as you so brilliantly wrote about if it had just been a 1:1 remake. I’ve seen detractors of the Destiny twist just waiving the effort of as just “Nomura Kingdom Hearts nonsense” without really taking the time to entertain the more nuanced themes at play. But hey, that’s ok because there are those out there – like you guys – that don’t shy away from wanting to see what’s on the other side. I am curious to know if your view of the Harbinger being a kind of reflection of the player has evolved or changed in any way as I think its been confirmed that the three whispers you fight are actually supposed to be Yazoo, Loz, and Kadaj not Cloud, Tifa, and Barret.

Aaron Suduiko · May 18, 2020 at 2:06 pm

Hey Miguel, thank you so much for your kind and thoughtful comments! I’m delighted that you discovered us and enjoyed the work you found; I hope you get the chance to check out our work on other games, too!

It’s funny that you mention the “Nomura Kingdom Hearts nonsense” complaint because we’re actually planning to discuss Nomura as an auteur on our very next podcast episode… stay tuned 😉

I hadn’t heard that the identities of Whispers Viridi, Rubrum, and Croceo had been confirmed, but that honestly doesn’t change much in terms of my view of Whisper Harbinger (just one interesting nuance, which I’ll mention below). There are two reasons for this, both of which I discuss in Endnote #7 in the article.

First, I hardly ever take into account what the authors of a story consider to be the “official interpretation” of their story. In my view, stories are best analyzed as “objects unto themselves”: what matters is how we understand what that storytelling object actually manages to do, not what the author meant to do with it. Of course, that doesn’t mean there’s no value to be gained in discussing what a game’s creators meant to be conveying through their game—that’s just not the kind of analysis that I personally do.

Second, I think that my interpretation of Whisper Harbinger still makes sense if the other named Whispers are Yazoo, Loz, and Kadaj—you can think of Yazoo, Loz, and Kadaj as extensions of the Whisper Harbinger’s will.

Here’s one interesting way that the nuances of my view might change in this instance: We typically think of “extensions of a player’s will” as avatars in games, and Yazoo, Loz, and Kadaj obviously were not originally avatars—indeed, they weren’t even in a video game when we first saw them. So there might be something interesting to say about how the corrupted desires of the player of Final Fantasy VII are warping the universe in such a way that their will is manifesting through fragments of Sephiroth himself. In my mind, that would just further underscore the sentiment that there’s something perverse about clinging to the plot of the first game and refusing to allow things to be otherwise, making it all the more triumphant when the player of Final Fantasy VII Remake bests the Whispers in the end.

Thanks again for reading! Hope you keep in touch.

Thomas Cortado · August 17, 2020 at 5:06 am

Un énorme merci pour cette si belle analyse. Curiously, the ending if FF7R remembers me the ending of Twin Peaks the Return…