The Hero of Time Project is an attempt to re-examine the narrative vacuum in the Legend of Zelda series between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, and to utilize the concept of fan fiction to logically fill in some of the gaps using information presented to us in existing lore.

Welcome back to the Hero of Time Project, where we, the Know-It-All Brothers, are analyzing what happened in the Zelda timeline between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, and taking a deeper look at the final chapter in the life of the Link known as the Hero of Time.

Characters in a wide-range of storytelling mediums will evolve over time in the context of their stories. It’s what makes Gandalf’s return and Frodo’s struggle so interesting to watch; it’s what makes King Arthur’s maturation and ascendence to royalty so impactful; it’s what makes Anakin’s betrayal so heart-wrenching. These are examples of a character’s spiritual journey, and they can make or break character development in a story.

Link’s spiritual journey and character evolution in The Legend of Zelda is an incredibly important part of the franchise, and we definitely wanted to take into account who he is and what that means for us writing the Hero of Time Project. With a character that operates as a silent protagonist, you might be wondering, “how does Link ever evolve as a character?” This was a question we had to consider at great length, and we inferred from the narratives of multiple canonized sources in order to arrive at the conclusions we’re employing in writing the Hero of Time Project.

In this article, we’re going to draw attention to Link’s spiritual journey in Ocarina and in Majora’s Mask, and argue exactly how this journey plays a huge part in shaping his character. From there, we’ll argue that Link’s spiritual journey also applies to the player directly, both in and out of the game. Finally, we’ll discuss how all of that comes into play in the story behind the Hero of Time Project.

The Origin Story of Link

When we first meet Link at the beginning of Ocarina of Time, he is an outcast in the Kokiri village. Unbeknownst to him, he is the only Hylian child among the Kokiri children, and thus, the only child without a fairy. We see that Link suffered quite a bit from feeling like an outsider based on the way the other Kokiri children, especially Mido, converse with him.

“Hey you! ‘Mr. No Fairy!’ What’s your business with the Great Deku Tree? Without a fairy, you’re not even a real man!” —Mido, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time

We also see it in the way The Great Deku Tree treats Link with a very special amount of care and attention: The Great Deku Tree knows that Link is different, and acknowledges it directly.[1] In all likelihood, despite his later heroism, Link probably felt incredibly insecure at the time—which is in total contrast to the Link we all know, the wielder of the Triforce of Courage, the Hero of Time.

Link meets Navi, his fairy, at the request of the Deku Tree, who is gravely ill. The Deku Tree informs Link (and, by extension, the player) that Link is responsible for cleansing the Deku Tree of his illness. Once Link does this, however, the Deku Tree informs him that he was already doomed before Link cleansed him. He delivers his final parting words to Link, and informs him that he will bring about great change, that fate has an awful lot in store for him, but that he must leave the forest to begin his journey.

This is the moment that, for Link, means opportunity; it means an escape, a chance to change. A lot of children, ourselves included, grow up waiting for a moment like this: waiting for the moment we find out that being an outsider was part of our destiny all along, that we were fated for something greater than ourselves. Opening on this moment, putting the player in control of a character at the onset of his awakening fate, gave that moment to a great deal of kids who might not have had it otherwise. This is where we make our initial connection to Link, and where we as players start our journey with our avatar. Link locates the Kokiri sword and uses it to vanquish the evil Gohma from inside the Deku Tree, catalyzing the rest of the events of Ocarina of Time.

The Great Deku Tree in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D.

Along his journey, he interacts with other tribes who dwell in Hyrule, both as an adult and as a child. Link travels to Castle Town to meet Zelda and other Hylians; he travels to Zora’s Domain to meet and help the Zoras (even going so far as to save their deity, Lord Jabu-Jabu), and vanquishes King Dodongo from inside Death Mountain, effectively saving the Gorons. During the course of these events, Link makes a huge impact on the realm of Hyrule. He interacts with races of people he never even knew existed, and learns a lot about the world and how it works. By extension, this is where the player is introduced to a great many of these people and places as well. In many ways, the purpose of the early sections of the story is to introduce the player and link to the world of Hyrule through Link’s adventures. It’s what makes the experience impactful, and relatable: both Link and the player are on a journey, discovering Hyrule for the first time.

At the end of Link’s journey, in the event that Link is successful and returns to his childhood,[2] Zelda informs him that she’s sending him back to “regain lost time […] where you are supposed to be… the way you are supposed to be…” So, Link returns to his childhood, but now with the knowledge of the future he helped to save, the knowledge of the people he spoke to, and the knowledge of the places he went.

This leaves Link in a very strange place: the people of Hyrule in this timeline don’t recognize him as the savior of Hyrule that he actually is. Being the quintessence of youthful altruism, he does not appear to be discouraged by this. Instead, he continues on his own journey.

Link in Majora’s Mask

When we see Link next, several months have passed since the events of Ocarina of Time. He has lost contact with an old friend, Navi,[3] and is searching for her. He somehow manages to wander into an alternate reality of sorts, only to have his ocarina stolen from him by Skull Kid, a misguided youth who came into possession of a very powerful and mysterious artifact known only as Majora’s Mask. Skull Kid transforms Link into a Deku Scrub and abandons him in the woods, leaving him to fend for himself. Link wanders into the basement of the Clock Tower, the centerpiece and namesake of Termina’s Clock Town, and is initially greeted by the Happy Mask Salesman: a creepy traveling merchant of sorts, who asks Link to retrieve his very powerful and mysterious artifact, stolen by some misguided youth (you know, come to think of it, we might have an idea of who took it).

Please go be creepy somewhere else.

Link accepts this task, finding himself once again intertwined in a world-ending plot set forth by a powerful, evil being. He follows a similar adventure to Ocarina of Time, traveling to places he’s never been and liberating people he’s never met from the evil influences of Majora’s Mask. He awakens the four giants, one from each realm of Termina, who, in return, assist Link in stopping Skull Kid from destroying the world.

The thing that separates the spiritual growth Link experiences in this game from the spiritual growth he experiences in Ocarina has a lot to do with the themes that come out of Majora’s Mask. In Majora’s, Link deals with a lot of darkened themes, with a lot of abstract surrealism, and with a lot of death and transformation. One of the major themes of the game are the three transforming masks (Goron Mask, Zora Mask, and Deku Mask[4]), each of which is inhabited by the spirit of a deceased member of the race.

The masks that transform Link into a Deku Scrub, Goron, and Zora, respectively.

To acquire these masks, Link must confront these spirits and attempt to ease their pain. Link must then don the masks and forms of the deceased, utilizing their talents to assist him in his quest, but also to tie up loose ends the deceased may have left, and to provide closure to the friends and loved ones of the deceased. One can only guess at what that must feel like to a child like Link, and what effects this would have on his development as a character as he grows.

Link’s Spiritual Journey

What we’re seeing here is the development of Link’s spiritual journey: the development of his character in relation to events in his life, and how that affects who he is at the core of his identity. Spiritual journeys are often backseat elements of character development, serving as a progress tracker of sorts in the ways that a person adjusts his or her perspectives on the world around them. In the context of a video game (similarly to a novel or film), the player/audience may be aware that a spiritual journey is happening without quite understanding the specific concept of what a spiritual journey is.

Some players of Ocarina and of Majora’s might have missed some of the key elements of Link’s spiritual journey, purely due to the way spiritual growth in video games often takes place behind the scenes or out of the player’s direct view, so to speak. Some of Link’s most impactful, character-defining moments were masked as checkpoints and progress markers in the context of the game. For example, where he retrieved the Triforce of Courage, where he met the Sages and learned of the Sacred Realm, and where he saved the world, twice; from an outside perspective, these may seem like just parts of the game. But, for Link in the Secondary World of Hyrule, these moments would have completely changed his life.

Because both Majora’s Mask and Ocarina of Time utilize time-travel as one of their central mechanics, Link ends each game in timelines where people have no knowledge of everything he did to save them. He’s forgotten by the worlds around him, and we, the players who do remember him, don’t see him again until over a century has passed.

The ruins of the Temple of Time in Twilight Princess make it clear just how long has passed since Ocarina of Time.

The next time we see him, the Hero of Time has taken on the gruesome form of the Hero’s Shade: a Stalfos-esque creature wearing ancient, gilded armor, missing his right eye, and communicating with Twilight Princess’ Link (the Hero of Light) through the Ghostly Ether—where we can see submerged elements of Faron Woods, Death Mountain, Hyrule Castle, Arbiter’s Grounds, and Snowpeak. This stark imagery is a far cry from the whimsical, youthful Link we saw in Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask.

On The Hero’s Shade

In many ways, the Hero’s Shade is one of the most significant iterations of Link in any Legend of Zelda game. Why? Because he is Link as we’ve never seen him before.

Imagine for a moment all of the things you know about Link from seeing him as a child and a teenager: he’s energetic, he’s brave, he’s good to the core, and sometimes he could be considered more than a little naive. If those descriptors sound like the quintessential young fantasy hero, that’s because that’s who he is! The quintessential young fantasy hero is a character trope often used because it creates a young, somewhat blank character that the audience can easily identify with and project onto. Keep in mind the phrase ‘somewhat blank’, meaning that obviously the character isn’t completely without his traits. For instance, we can surmise that in order to do the incredible things that Link does, he would have to be very brave.

But Hero’s Shade represents many sides of Link’s character that were previously unexplored. Shade is physically imposing: in the game, Shade actually stands a good foot taller than Twilight Princess’ Link. Combined with Shade’s skeletal appearance, he’s scary, and deeply imposing. Shade is also a harsh teacher, choosing to test Link’s abilities with essentially live-combat exercises.

Link (Hero of Light) and Hero’s Shade clashing swords.

Who is this person? We hate to say it, but we simply don’t know. There’s no material to cover or reconcile the age difference between the young, exuberant child we knew, and the tall, dark creature that stands in front of us in Twilight Princess.

The Hero’s Shade is also significant because he has the capacity to evoke some pretty jarring themes in both the character of Link and in the way he’s clearly tied to Hyrule’s complex metaphysical side. The three virtues of the Triforce—courage, wisdom, and power—are one of the extra important and most frequently used themes. Shade, as the spirit of the Hero of Time, is still an avatar of courage; but he displays wisdom through his teachings, and he displays power through his presence and action. He may not be the literal bearer of the full Triforce, but he could be seen as a more metaphorical bearer of the values that the Triforce represents. These are not just fleeting side dishes on the platter that is the Hero’s Shade: they’re a big part of your experience with him in game. They also combine to show a great deal of growth on the part of the Hero of Time: not only is he representative of one piece of the Triforce, but now he also displays all three of them as prominent aspects of his character.

In many ways, Shade represents something even scarier to us, not just as gamers, but as people: change. If we were harsh, unpleasable critics, we might call Shade the metaphorical rotting corpse of Ocarina of Time. He’s a reminder that Ocarina of Time was released in 1998. At the time of our writing, that’s 19 years ago.

Promotional Art for Ocarina of Time’s initial release

He also potentially represents some good things, too. As the Hero of Time, Shade has really stepped up to the plate; it seems no matter how old Shade became, even to the point of death, time could not stop him from saving the day. That’s the Hero of Time we, all of us, grew up with.

In fact, let’s hold on to that last thought for a few paragraphs.

Who is the Hero of Time?

As young Link is an avatar of courage and youth, he is also a somewhat blank character. Not to say that his personality is completely non-existent, but, as stated above, he is the quintessential young fantasy hero. That caricature is a specially tailored type of hero designed to be ultra-relatable to the viewer/player. Think about, for a moment, characters such as Frodo, or Luke Skywalker, or Sir Arthur from Ghosts and Goblins… no one? Ok. But characters like these are built on the idea that their story is just beginning, and, being young and excitable, they become easily identified with by a good portion of the audience who are also young, and whose ‘story’ is also just beginning.

A Young Fantasy Hero meets his demise.

Link is also a silent protagonist, which is a somewhat recent character type that gained popularity with video games. The idea is that the character does not speak ever, or almost never. A character that does not speak, or emote, essentially has no personality. think about how Link, in any game, doesn’t really have an opinion on what he’s doing. What did Link say when the Deku Tree entrusted the fate of Hyrule to his hands? How did he feel when Skull Kid trapped him underground at the beginning of Majora’s Mask?

The problem is, of course, that the story wouldn’t work if the main character had literally no personality and never reacted to anything—and the human mind tends to agree. Not to say that Link has no personality, but it’s also not accurate to say his personality is whole, or would make a believable character when placed by itself. Link doesn’t possess a full-blown personality as much as he possesses a set of core ideas that make him up; the rest is a less strictly-defined set of traits where the player projects themselves onto Link. When confronted with this strange, and reality-bending scenario, your mind will superimpose pieces of your own identity onto the character to fill in the blanks. Link has no actual reaction, so your reaction becomes Link’s reaction. Your fears become his fears, your monsters become his monsters, and so on. In effect, the character, for the purposes of storytelling, is the audience and the audience is the character.

A Young Fantasy Hero meets his Demise.

The amazing and frankly beautiful thing is that you can become so wrapped up in this fusion of self and character that it’s almost like Link not only is reflected upon, but also reflects aspects of himself back onto the player. You begin to feel his energy, his curiosity. Every time you start up Ocarina of Time, Link is still young, and still innocent. As you are Link, who conquers evil, and saves the princess – so Link becomes for you an almost eternal representative of good, and heroism. As a result his image is forever planted onto the mind of the viewer. It is then you who feels young again, who feels maybe a little restored. It is you who gets to recapture your youth and childhood, your sense of innocence and adventure, and maybe even your sense of self.

Video games can be a strange and difficult means of escape, restoration, and change—in the same way that millions of people have found many of their own life lessons, and culture-changing moments in the pages of books or in the frames of movies. Link to us (as in all of us here on the outside) is an icon who has had a tangible effect on our culture. It’s changed how we view fantasy, gameplay, cyclical storytelling, and more than we have time to go into here. For the most diehard of fans, Link’s effect on our culture, on our personal lives, and on the fictional people of Hyrule is deeply profound.

It is in this way that Link is the constant conqueror, the hero who crosses not only time in the story, but he crosses time outside of the story—so that whenever you start up your N64, he is your Hero of Time.

What does that mean to us?

Maybe somewhere along the road we’re beginning to lose our connection to Link—after all, how long can you really stay totally identified to innocence, or to youthful energy? As we, the authors, continue to play, year after year, sometimes we catch ourselves starting up Ocarina in some desperate attempt to recapture a past that simply can’t be experienced again: our childhood is over, your childhood is over; and Link didn’t grow up with us—he stayed the same.

If we’re being honest with our readers and ourselves—and we feel that we have an obligation to do so—we don’t feel innocent anymore. We don’t feel that young naivety, that youthful energy, that willingness to somersault across Hyrule Field for hours on end, cutting grass for money and smashing pottery. It’s truly amazing, in a sad sort of way, that Link remains so untouched by the malaise of time. After nearly two decades of our lives, we can always boot up our cartridges and see Link wandering around Hyrule in a perpetual state of awe, still fueled by nothing more than courage and altruism in his quest to save the day again and again and again.

It’s heartbreaking that we can’t seem to recapture that connection we had with Link. And for those of us who related so much to Link in our childhood, it doesn’t just feel like a loss of innocence or an inability to recapture whimsy: it feels like a disconnection from our true selves. From who we were, not just as kids, but as people. It feels like realizing that a part of our identity has died, has been lost forever. Unrecoverable. You’ve return to the game and find you can no longer relate to Link in the same way, and that can be jarring because it shows your identity has changed with time.

But what happened when we turned off our Nintendo 64 for the last time? What happened to Link when we stopped playing the game, when we started growing up, our voices started to change, and we started (thinking about) talking to the opposite sex?

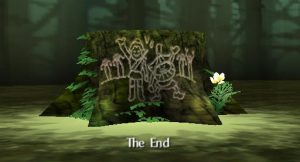

Where did Link go after Majora’s Mask ends?

The parting gift left for the Hero of Time, from Skull Kid.

He grows up. He becomes Adult Link, naturally, over the course of years. And then, naturally, he becomes Old Man Link. But if we’re to believe in the Secondary World that is Hyrule, and in the Secondary Belief that Link’s fate is tied indefinitely to the Triforce of Courage, then we have to believe that Link doesn’t ever change: that he will always be an avatar of good, an edifice of exuberance, and the icon of innocence and courageousness in the face of true evil. We have to believe that, ultimately, Old Man Link would be just as brave, just as courageous, and just as outright youthful in nature as he was when he was a child. That’s the nature of the quintessential young fantasy hero.

Even more incredible is that Young Link does these things because they are a part of his nature: he does good almost without thought. Old Link, by contrast, would have an entire lifetime of growing, both physical and mental, to choose to leave that nature behind if he wanted to. His dedication to goodness is all the more amazing—not because amazing comes naturally to him, but because he is amazing by act and deed. He can, for the first time, truly choose good in the fullest sense because he is a fully developed hum—well, Hylian being.

If we believe that Link remains true to himself throughout life, then we must believe that Link continues on other adventures; that he saves other lands, defeats other evils, and slashes other chickens. And if we believe that he continues living and growing, then we accept the possibility that the story might live and grow right alongside us—that, behind the scenes, between the games, the story of the Hero of Time continued onward. We’ve just never seen that side of him.

But we believe that, if we could see that side of him, it would look a lot like this:

Damien Canderle’s conceptual illustration of Old Man Link, and the single image that kickstarted our desire to tell this story.

Grizzled by time, sure, but it’s easy to imagine this character kneeling down to a young child while donning a happy, grandfatherly facial expression, chuckling quietly to himself. It’s easy to look at him and wonder what sorts of adventures he’s been on, what he’s seen, and where he’s gone. But, most importantly, it’s easy to look at this character—with whom we’re so familiar, whom we’ve seen grow old and young again, don masks that changed his physical form, and play songs that stuck with us for years—and to feel something… familiar. And it becomes so much more evident when we take a step back and look at ourselves.

We’ve grown old.

This is actually one of the ultimate struggles for fans of the Zelda franchise. This is why so many fans are so divisive about their favorite Zelda game, and why everybody thinks that the best Zelda game ever released was the one that came out when they were a child. Because that’s when the story was most relatable to them.

The Definitive Zelda Argument, from Dorkly.

So, how do you make The Legend of Zelda relatable again? You bring the player closer to the avatar. You allow Link to grow up, just like the player did. You age the story. You age the world. You give the player something that they long for—a return to their innocence, to their strengths, and to their courage—and you give it to them in a way that works.

The Hero of Time Project

We’ve been trying to find that “way that works” for a long time, and it’s why, in our story Hero of Time, Link is old. Link is 76 years old, to be exact. By aging him this way, we allow players to return to a Hyrule both as themselves and as avatar. We use merged perspectives, where the player and avatar are both experiencing the world and events within it in ways that parallel the other. For Link, it is a return to the Hyrule in which he grew up. It’s a return to places he knows, people he knows, and reminders of the journey he once went on. And for the player, it’s exactly the same.

An online survey conducted in 2014[5] showed that, at the time, a staggering majority of fans were between the ages of 18-34. That means that, today, all of those fans are now over 20 years old—twice as old as Link was in Ocarina of Time, and far, far from the mindset of a prepubescent child (perhaps not as far as we’d like to think, but the point still stands). And because so many of our collective favorite things are now from an era gone by, we, too, feel so incredibly old.

You might wonder why we chose to make Hero of Time’s Link so much older than the fans of Ocarina of time. Some of it is an exaggeration keying into the subjective feelings we have of feeling and being old, and feelings we, as fans of a franchise older than us, feel when we see children so much younger than us going on those Zelda adventures (because, damn it, those aren’t our Zelda adventures). A lot of it also has to do with covering as much of the historical gap between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess as possible.

And, a lot of it has to do with where we’re taking the story. But you’ll have to wait for that part.

At the end of the day, Hero of Time presents a relatable, fresh-but-not-exactly-new Zelda story. It gives the player a chance to fulfill those desires of returning to their childhood. It fills in the gaps of missing information between some of the most impactful games in the series. And, it closes a chapter in the life of Link, making him not only the hero who travels through time, but also the hero who conquers it wholesale.

The Hero of…

Well, you get the idea.

[1] “It seems the time has come for the boy without a fairy to begin his journey… The youth whose destiny it is to lead Hyrule to the path of justice and truth…”

[2] Link leaves the Adult Era Timeline, traveling back and creating the Child Era Timeline: A complicated event we expanded on in our Missing Link article.

[3] “Link set off on his horse, Epona, who lived at Lon Lon Ranch. Months passed as he wandered in search of his companion, Navi, eventually losing himself in a mysterious forest.” (Hyrule Historia (Dark Horse Books), pg. 110.)

[4] The Deku Mask is implied to contain the spirit of the Deku Butler’s Son. We can see a petrified Deku Scrub in the opening tutorialized section of the game, and the Deku Butler provides this bit of dialogue when you speak to him while wearing the mask: “Actually, when I see you, I am reminded of my son who left home long ago… Somehow, I feel as if I am once again racing with my son… I am afraid I may have tried too hard to outrun you. As old as I am, I am still a fast competitor. Just like when I raced my son… Please forgive my rudeness.” —Deku Butler

[5] It also displays how the top three games that were the first Zelda game some fans had ever played were: Ocarina of Time at 40%, A Link to the Past at 14%, and the original The Legend of Zelda at 13%.