Introduction: Why We Should Care about Modern Retellings of Myths

Most myths are told in a straightforward fashion: God 1 did this, and God 2 reacted to it by doing X. God 3 created Y, and Y is the reason that (for example) we have seasons. There is no interpersonal narrative, nor any real scope of how the character feels. All we have to judge a character on is their actions and outward emotions in their simplest forms (e.g., God did X, Goddess grew angry).

This kind of storytelling creates a blank space for the creative mind. With behaviors that are too plain—behaviors that have no explanation—the imagination wonders what was going on inside the characters’ minds as they conjured a curse or ventured out to do an impossible task. This blank space acts as a conduit to consciously create more to the mythological world than the content that is told, whether the additional content is created through analytical study or through fiction that elaborates on the myth.

The latter of these two options is interesting because, if an author decides to rewrite a myth as a work of fiction, they have to take a mythic character and start to reshape them: they must sculpt them as if they were a character of the author’s own creation. The underlying source story is still present, but authors must develop complex characters, answering the question of why the characters are the way they are in the myths.

This analysis only applies to short-form mythologies, or mythologies that don’t delve into the deeper meaning of the story or character values. This means that I am excluding epics, such as The Iliad, The Odyssey, Gilgamesh, Ramayana, etc. They present mythologies differently because of their different form.

A map of mythologies from around the world. Created by Simon E Davies.

On the one hand, authors have taken existing mythologies and changed them to create a different narrative experience while preserving the same underlying story. In most cases, the authors fill in the blank space of the mythology, adding introspective character development and narrative tension to the story. On the other hand, since no one truly “owns” a myth (in contrast to the kind of copyright that can help authors own their fiction today), many authors can take great liberties in adding their own features or changing the order of events completely. Mythologies almost invite the readers to do this with their blank-space storytelling.

The story of a myth is what many people believed long ago as truth, but in the present day, when other religions dominate the scenes, ancient mythologies are viewed more as fascinating storytelling for the imaginative mind. The characters and setting imagined in mythology might have existed in a different realm or time different from ours. That is what makes myths so exciting: if, in a parallel universe, ancient Egyptian mythology was actually real, how would humans behave? How would the gods behave, and would they act like their mortal counterparts? What would the relationship between gods and humans be like?

Mythology takes us to another creative plane, one governed by an initial, underspecified set of events, settings, and characters. This plane is close to the realm of fantasy, but the two differ with respect to how ancient and set-in-stone the mythos is. In mythology, certain gods have been around since the beginnings of Earth, while some mythological places actually exist on Earth and are still considered sacred to this day. In fantasy, there are a set of rules (at least in good fantasy: there must be rules, so that the fantastic does not seem undefined and out-of-control), but the author of the fantastical world determines these rules. Between Stan Lee’s Marvel Universe, Shigeru Miyamoto’s The Legend of Zelda, and J.R.R Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, each fantasy has its own set of rules. In mythology, on the other hand, if you want to write a story about Hinduism and its expansive universe, you must adhere to the initial rules written long ago—you cannot make up a god or a place and claim that since you wrote it in a Hindu mythos world, or that it is now part of Hindu mythology. You must be faithful to the source mythology if you want to dabble in its realm. When an author rewrites the mythology by adding extra storytelling elements, then the realms of fantasy and mythology meld together: old rules mix with new.

Amaterasu looking at the Celestial Brush God Yomigami, based on the East Asian Zodiac.

In this article, I look at two different works of fiction that focus on the same myth: Catherynne Valente’s novel, The Grass-Cutting Sword, and Clover Studio’s video game, Okami. I am going to compare the two—specifically, I use The Grass-Cutting Sword as a stepping stone to show how you can go beyond the narrative limits of an original mythology to make fantastic video games.

Both adapted stories tell the Japanese mythic story of the storm god Susano-o, the sun goddess Amaterasu—his sister—and the beastly snake monster Orochi who threatens to devour the maiden Kushinada. In The Grass-Cutting Sword, Catherynne Valente does not change the plot too much, but rather focuses on the mythological characters, giving them more rational personality that readers can understand and judge. Conversely, Okami presents the mythological characters in an entirely different frame, adding new characters, plot elements, and personal motivation for the protagonist, enemies, and you, the player. Both the novel and the video game take the blank space of the original myth and contrast new perspectives; however, The Grass-Cutting Sword shows the limitations of reimagining the myth as a novel, while Okami transforms the blank space into something beyond the myth.

Understanding the Source Myth

In order to understand how The Grass-Cutting Sword and Okami remake the mythic story to capture the audience, we must first be acquainted the original story given to us in the Kojiki.

Izanagi and Izanami on the Heavenly Floating Bridge at the beginning of creation.

In the original Kojiki myth, the first beings to exist were Izanagi and Izanami, the “parents” of the world. The two birthed many deities during their time together, and those deities then made the land of Japan. When Izanami gave birth to a fire spirit, she was badly burned and eventually died because of it. Saddened, Izanami decided to follow his wife to the Underworld. He found her in the dark, and she said she would gladly come back—as long as he did not look at her in the meantime. Izanagi waited a long time; then, at one point, he created a torches and saw the decaying form of Izanami. He fled, and Izanami chased after him in her disgrace. Izanagi escaped, and, to wash off the death from his body, cleaned himself in a river. From washing his left eye, he created the all-mother sun-goddess Amaterasu; from his left eye, he created the moon god Tsukuyomi; and, from his nose, the unpredictable storm god, Susano-o, was born.

Susano-o was exiled from his cloud home after Izanagi grew furious with his disruptive behavior and his desire to see his mother, Izanami. Before he left for exile, he visited his sister, Amaterasu, in Takamagahara (the celestial place where many of the gods resided). He then proceeded to run around destroying gardens and throwing his excrement around, typical for the destructive god. Amaterasu tried to ignore her brother’s havoc, but eventually got fed up when he dropped the piebald colt of heaven through a roof, killing it. Amaterasu was frightened by the sight and hid in a cave, casting heaven and earth into darkness. Many spirits had to persuade and somewhat trick her to get her out of the cave, while kicking Susano-o out to the earth.

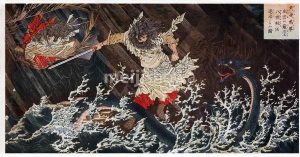

Depiction of Susano-o (center) fighting Orochi (left) and protecting Kushinada (right).

Finally exiled on earth, Susano-o saw chopsticks floating down a river and came across an old man, old woman, and a maiden, their daughter Kushinada crying. A terrible, eight-headed serpent, Orochi, had eaten the parents’ first seven daughters, and was now coming for the last one. Kushinada, the last daughter, had not been eaten yet, nor did she want to been eaten by the monster.

Susano-o agreed to slay Orochi if he could then marry Kushinada; everyone agreed to these terms. He then turned Kushinada into a comb and put her into his hair for protection. He then ordered the parents to prepare sake brewed “eight times over to make it strong” (26) and create an eight-door fence. They did so, and placed eight bowls of strong sake at each door.

Orochi appeared, and, placing its heads through all eight fences, drank itself into a stupor. Susano-o then killed the fowl beast, cutting off each head. He took a sword from corpse—the Kusanagi-no-tsurugi, or The Grassing-Cutting Sword—and wed Kushinada. There is no reference in any text that Susano-o actually travelled to Yomi to see his mother (Yasumaro, The Kojiki).

The Kojiki.

It is important to recognize the myth’s origin in The Kojiki because the ancient book is mixed with ideas that set up the Japanese government, cultural understanding, and spiritual beliefs. The text is the one we look at most frequently to understand Japanese culture and, in many cases, the political basis of Shinto religion (thanks to Dan Hughes for discussion here). That being said, I want to be clear that I am analyzing the myth solely for its storytelling and characters, not for its religious context. (This will be especially important when I analyze Amaterasu and Susano-o individually in Part 2 of this article.)

Storytelling: How a Novel Leads to a Game

It might seem strange that I am comparing a novel to a video game. They are two very different forms of fiction, and comparing how each transforms mythology might seem obtuse. However, that is exactly why I am comparing the two. A novel can only do so much with the original mythology. A video game, on the other hand, can expand and reinterpret the myth to a much greater extent. In fact, as I will argue, a video game must transform the myth in this way: it must take the myth’s blank space and do something unique with it, or else there would be no tension, no driving plot, and thus no game to play.

The Grass-Cutting Sword: Laying the Foundation for a More Intimate Myth

Catherynne Valente mostly keeps to the original myths of Susano-o and Amaterasu, the killing of Orochi, and of Izanagi and Izanami, but she presents them through specific points of view: those of Susano-o, Orochi, and Kushinada. Susano-o broods in resentment against his father and sister, yet mournfully desires his mother again (both in the non-sexual and the Oedipal way). He even launches a tirade against monks, retelling the story of Izanagi and Izanami in horror and anger.

In between these Susano-o chapters are chapters from the perspective of Orochi, who, in The Grass-Cutting Sword, is an amalgamate of a horrid beast and the seven maidens that it eats. With each Orochi-centric chapter, the narrative switches between the newly selected maiden and Orochi—denoted by different syntax for the voices of each maiden, and italics for Orochi—until they combine into one stream-of-conscious voice. Kushinada’s voice starts like this—like the rest of her sisters—but ends with her alone, symbolizing Susano-o killing Orochi, and thus her sisters, whom Orochi consumed.

The Grass-Cutting Sword, by Catherynne Valente.

These shifts in perspective paint the original myth in a darker and melancholy light, rather than as a heroic and redemptive battle. In general, myths are told in a third-person omniscient point-of-view, without personal feelings or inner thoughts. Rather than writing a more “exciting” or “action-filled” plot to retell the myth, Catherynne dives deeper into the characters of Susano-o, Orochi, and Kushinada, writing a story about interpersonal conflicts and desires. Now we, as readers, get to see a different meaning to the story: we get to the see the challenges Orochi faces, the bitterness Susano-o harbors, and the sorrow Kushinada develops.

The tension in the story comes from Susano-o and Orochi wanting to achieve their goals and facing the terrible obstacles that lie in their way. Susano-o’s problems lie mostly in his backstory: growing into issues of familial and self-directed hatred. Orochi, on the other hand, must deal with a disturbed idea of family and sisterhood, struggling to find a sense of belonging. Other subplots are added to the plot to create a deeper sense of character motivation to the story. Kushinada does not want to be rescued by Susano-o; instead, she wants to be eaten and stay with her sisters forever. Izagami is abusive and rapes Izanami, causing her to resent him forever. Contrary to the original myth, Susano-o actually does descend into the underworld to his mother in the end. All these details are the blank space of the myth, which Catherynne has shaped and given form, whether that be in the backstory, internal grief, or the characters’ desires.

Susano-o fighting Orochi, with Kushinada in the background.

This deeper involvement with the characters gives the reimagined myth a stronger hold on the readers: we are more invested in the success of Susano-o and Orochi, even though the two have very different and contrasting goals. Since the myth is written through the eyes of the actual characters, we care more, because we want the characters to solve their internal struggles and external obstacles. Original myths, for the most part, don’t facilitate reader investment to this extent, due to their lack of interpersonal narrative.

Imagine, then, if we take the complicated character perspectives of The Grass-Cutting Sword and put them into a video game. If writing a novel through a mythic character’s perspective can get an audience to care, then writing a myth into a video game will get the intended audience care even more, because of two gaming concepts.

- The player of a video game has a greater stake in the story and more to lose throughout the story (i.e. they can literally lose the game).

- The player is more directly emotionally invested his/her avatar and even the characters the avatar influences (assuming the game’s design is good).

Taking personal conflict and making it interactive can make an audience feel like they slowly uncovering the bigger picture of the story: the greater myth that encompasses the narrative. Now, instead of reading text, given to them like in a novel, the player must instead trigger certain events and engage with specific characters in order to reveal the storyline, becoming personally involved with the development of the mythology itself.

Okami: Building a Mythic World that Centrally Involves the Audience

In Capcom’s Okami, Japanese mythology comes to life as the player explores the world of Nippon (Japan). Adapting a myth into a video game is tricky, because most myths by themselves do not work well in game format. Even if game creators added to the blank space—say, more enemies that hinder the gods or heroes, puzzles that take you from Plot Point A to Plot Point B, or side-quests that have nothing to do with the myth itself—the myth’s plot typically cannot sustain a full and complex game. This is because myths are too typically too plain—and, more importantly, too linear—to be adapted into a well-written story for a game.

Official artwork of Susano-o (left) and Amaterasu (right) fighting Orochi (center—and left, and right… just, everywhere).

Games must change many things in the original myth, or else the game would not be able to give the player any semblance of agency. In a video game, the gods cannot just wave their hands and will something into existence, because the players have to have something to do in the game. In order to create a story with player agency, what many game creators do is rewrite the myth completely. They keep certain components, like gods, their powers, enemies, places, or events; however, the order of events often changes, and entirely new story content that is essential to the game’s plot is added. Games also follow Valente in adding complexity to myths’ characters, sometimes completely altering or refreshing a mythic figure’s personality.

Before I can explain how Okami achieves all of this, we need to have the game’s plot in view.

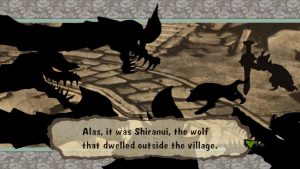

The recounting of the reimagined legend in Okami.

The game starts with a prologue: one hundred years ago, the hero Nagi and his white wolf companion, Shiranui, joined together to defeat the eight-headed serpent Orochi, saving Nagi’s love, Nami. With the last of Shiranui’s power, they sealed the daemon away in a cave.

One hundred years later, Nagi’s descendent Susano-o—a mortal man —finds the cave, and, declaring he does not believe in the legend, breaks the seal and frees Orochi from his prison. At the same time, the cherry-blossom spirit Sakuya calls forth Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun. She appears in the form of a white wolf, whom villagers believe to be the reincarnation of Shiranui, which is half-true: one hundred years earlier, Shiranui was the reincarnation of Amaterasu.

Amaterasu and the player speaking with Sakuya, guardian spirit of Nippon.

Once Amaterasu returns, she leaves on a quest to stop the beast Orochi and cleanse Nippon of evil. She is accompanied by the tiny sprite named Issun (who does all the talking, because Amaterasu is a wolf and therefore does not talk). The citizens Kamiki Village, where Susano-o resides and Amaterasu woke up, at once decide to confront Orochi. Kushinada, Susano-o’s love interest, makes the 8 Purification Sake needed to defeat Orochi.

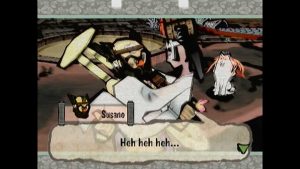

Amaterasu goes on several different quests to reach Orochi (each of which is not part of the initial myth) and then returns to Kamiki Village, only to find it in turmoil. Susano-o drank the 8 Purification sake and locked himself in his house, admitting that he was the one who released Orochi. Determined not to die, Kushinada takes it upon herself to defeat the monster, and tells Susano-o to summon the courage to do the same.

Amaterasu takes Kushinada to Orochi’s cave, and they face the beast. Before she is nearly defeated though, Susano-o comes to save the day—or at least, he thinks he is. Amaterasu still does all the work, but she does not let Susano-o know about this. In the end, they slay the beast, and Susano-o and Kushinada go back to the village happily in each other’s arms.

A scene of victory for both Susano-o and Kushinada, following the defeat of Orochi.

The game reshapes the original myth of Susano-o, Amaterasu, Kushinada, and Orochi completely. The main plot—Susano-o saving Kushinada from Orochi—has not changed, but everything else has. Just to name a few key points:

- Susano-o is not a god, so the original myth’s plot of him being kicked out of heaven is gone

- Kushinada does not have seven other sisters, but instead is an expert sake brewer

- Amaterasu is very much involved in the defeat of Orochi and saving Nippon (and is also a wolf)

Not only have the backstories and roles of the mythic figures transformed, but the relationship of the Susano-o/Orochi myth to other Japanese myths has transformed as well.

When you are familiar with both the original myth and the reinvented Okami myth, you immediately compare the two and, hopefully, notice how much more human the Okami story is than the original. It focuses on Susano-o, Kushinada, and Amaterasu overcoming mortal fear in the face of overreaching evil (Something we will see even more vividly in the second part of this article). Because of this, the tale in Okami is pseudo-mythopoeic: it borrows heavily from original tale, but it nonetheless creates a separate world entirely. The source of tension is reworked to make the player interested, and yet the narrative is set in a place and time that provides the same wonder as the original mythology. Since the Susano-o/Orochi tale only comprises about ⅓ of the game, the rest of the story follows the same mythic endeavor: it derives its tales from ancient myths, but reworks them into something the player can enjoy, explore, and undertake.

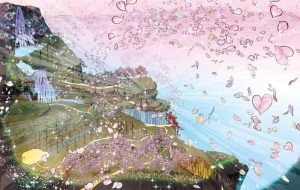

The landscape of Kusa Village.

The tension in the story derives from Amaterasu trying to acquire power to become the goddess that she once was, from her aiding the (mis)endeavors of Susano-o trying to be the hero that his ancestor was, and from her supporting Kushinada’s bravery and willingness to change the story herself. Therefore, Okami is an interactive narrative where the tension constantly spurs Amaterasu—and thus the player—forward, and also reveals a vast world to transverse and explore from the player’s own perspective, at her own pace. The tension appears in changes of landscape—from beautiful skies and fields to darkness covering the land (with literally cursed zones), from changes in music, and from dramatic changes in plot points, full of twists and impending doom. The reimagined story of Susano-o, Orochi, Kushinada, and Amaterasu keeps the player on her toes and eager for more.

As I said before, it is difficult to take a myth and make it into a game without boring the player. It is much easier to (a) write a novel to focus on character development more than the plot, like The Grass-Cutting Sword, or (b) take mythic characters and create new story altogether. For example, the God of War series uses the ancient gods and heroes from classical Greek mythology, but not the actual stories themselves. The mythic tales are only reminders of what heroes and gods did in the past: in the game, the new, present heroes must use that knowledge to save the world from an entirely new plot that’s never been seen before.

God of War is a game where you kill off many (if not all) the gods and heroes of the Greek pantheon.

Okami escapes the danger of being boring by making drastic changes to characters and plot points, but manages to do this while still telling an engaging and coherent version of the Susano-o and Orochi myth—not an entirely new story, like God of War.

Also, taking mythic characters, landscapes, and beasts and putting them in different time and space is one thing; using the characters and story within the same mythic time and space is another, because it is hard to rewrite a pre-existing myth for the current age and not drastically change core aspects that make the myth unique. When trying to determine the differences between myth, legend, and folktale, William Bascom argued that myth exists in the “remote past”—mythic time—and in a “different world; other or earlier”—mythic space (Bascom, 5). As another example, the Percy Jackson series is set in a different time and space compared to the original myths from which it draws inspiration: the young heroes run around in present-day (or at least in the late 2000s to early 2010s) and in various parts of America (for example, Olympus is now at the top of the Empire State Building, instead of on Mt. Olympus). So, just with this information alone, it’s clear the Percy Jackson series is not a retelling of the original Greek myths.

This point might seem a bit obvious, you can use the same logic to analyze other, less clear-cut mythic works of fiction, and see if they are mythic spin-offs or true retellings. It is much more difficult to pull off the latter, but Okami does so successfully, despite major characters and plot points being altered.

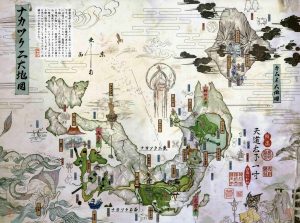

The official artwork of the map of Nippon in Okami, detailing all the places Amaterasu visits.

The time and space of the original myth is still present in Okami: it is set in ancient Japan, and it exists in an “other” Nippon: a world where monsters and gods are real, and where people’s problems can be solved or worsened by a variety of spirits who share the same space as them. The original myth is set in this same time and space: back in Japan’s distant past, under the influence of gods and spirits. The lush landscape—Mt. Fuji in the background and the cherry blossom trees blooming; the Japanese traditions and culture, such as temples, weapons, calligraphy, and food that you find for health; and the legendary creatures, like the nine-tailed fox, cat friends, moon fish, and spider queens—all contribute to giving the retelling of the myth a visually rich atmosphere. It makes the player both believe that mythic Japan could have definitely looked like Okami, and want to venture into the rest of Japan to see the country for all its mythic beauty.

Unlike The Grass-Cutting Sword, the Japanese mythology presented in Okami differs because it provides an explorative and interactive landscape: a colorful, 3-D, and highly stylized arena for player, with visual scenery that allows the player to vividly imagine themselves within this new Nippon. This is a mythical world that is represented much more robustly than in either the Kojiki or in The Grass-Cutting Sword.

Amaterasu in Shinshu field.

Conclusion: The Value of Enacting a Myth

Both The Grass-Cutting Sword and Okami develop the ancient story of the Susano-o and Orochi myth into enticing narratives, yet the latter metamorphoses into a more emotionally engaging and representationally rich piece of mythic fiction. The Grass-Cutting Sword, then, can be seen as a stepping stone for Okami in terms of storytelling: the plot of the novel contains two narrow yet intense perspectives of Japan, delving inside the characters’ minds through text, yet the plot of the game encompasses a much wider view of Japan, and allows the player to actually traverse it.

The players of Okami move beyond The Grass-Cutting Sword’s techniques of monologues, personal backstories, internal struggles, stream of consciousness: instead, they enact the action, characters, and divine will within the myth—prompting dialogue, defeating enemies that block thwart characters, and carrying others on Amaterasu’s back to their destination. The player cares about Amaterasu and wants to restore the fallen gods (not to mention gain cool powers), refuses to let Susano-o bumble around like an idiot instead of doing the right thing, and feels for Kushinada when Orochi chooses her to be his next victim. Instead of reading the characters’ minds to piece together the plot, Okami takes the next step and allows players to experience the plot by personally motivating the characters to continue forward throughout the plot. The creators of the Okami designed new possibilities in the blank space of the mythology, but ultimately, it is the player who makes the myth actually happen.

Official artwork of Shinshu field, revived.

Works Cited

Bascom, William. “The Forms of Folklore: Prose Narratives.” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 78, No. 307 (Jan. – Mar. 1965). American Folklore Society. pp.3-20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/538099

Frye, Northop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Atheneum: Princeton University Press, 1966. Print.

Hughes, Dan. Personal Interview. 30 August 2017.

Kamiya, Hideki. Clover Studio. Okami. Capcom, 2006. Nintendo Wii.

Valente, Catherynne. The Grass-Cutting Sword. Prime Books: Canada. 2006. Print.

Yasumaro, O No. An Account of Ancient Matters: The Kojiki. Trans. Gustav Heldt. Columbia University Press: New York. 2014. Print.

Continue Reading

- Navigate this feature: | Part 2: “How Okami Transformed the Meaning of Characters like Amaterasu” >

- This article has been Critically Reviewed: read “Okami’s Lessons on Religion, Video Games, and Storytelling”

1 Comment

Aiden · February 2, 2018 at 3:46 pm

Heya. Haven’t read the article yet but was just wondering: should I immerse myself in Japanese mythology prior to playing the game or is it better to learn about it through the game?