Once upon a time, video games were seen as a medium not to be taken seriously, a medium meant only to entertain and distract children. This isn’t entirely surprising, seeing as the company that arguably created the video game market as we know it today, Nintendo, exclusively produced toys before they released the NES.

Originally, Nintendo was a company that produced playing cards, like these.

Even today, this first impression persists in certain circles of those who have never touched a controller. Given this, it’s understandable that many developers will want to take games previously thought of as childish and make them more “mature” in an attempt to prove these people wrong and gain more respect. Unfortunately, we as gamers have learned from experience that this may be a more difficult task than many developers are prepared for.

Ahem.

There is a challenge faced by video games specifically when it comes to maturity. The medium presents a unique problem in this area because video games encourage audiences to impose their will upon the art. This being the case, it’s all the more likely that an observer may, if primed to expect immaturity, play a game in an immature way, ignoring any mature ideas that may be present. That said, other mediums have already dealt with an analogous problem; in books, for example, it is possible that symbolism may go over a reader’s head. Authors of books have developed methods to communicate to audiences that they should expect to see relative maturity in their stories, and video games that want to be taken seriously as mature storytelling can use the same methods.

What are those methods, then? And what do we even mean when we say that a story is “mature”? For the purposes of this article, we will define a mature story as a complex one: many different interrelated ideas and themes are present, with at least one of these being explored in depth. There are a number of different tools authors can use to explore a theme in depth, regardless of the medium; one of the most commonly used methods, and the one most relevant to this article, is the creation of well-rounded characters with clear motivations: characters who have multiple personality traits that come together to make them who they are, as opposed to one-dimensional characters whose personalities can be expressed with only a single description, with no nuance. As an observer, one easy way to spot a well-rounded character is by gauging your emotions: if you feel an emotional connection with the characters in a story, the odds are good that they have successfully been designed to be well-rounded. If fictional characters are well-rounded, then that means they are relatively similar to actual people; they may be so similar, in fact, that they can evoke empathy from audiences, just as if they were real people and not figments of an author’s imagination.

One would expect video games to have an advantage when it comes to telling mature stories: since video games are such a young artistic medium, surely they can take the best ideas from other mediums that paved the way, emulating their successes and learning from their mistakes. Why, then, do some video game series struggle with the transition to more serious storytelling, while others make it seem so effortless? In order to answer this question, I’ve considered three similar series (and ones that I happen to be quite fond of) and tried to discern the reasons for their mixed levels of success at trying to tell more mature stories. After examining the PS2 holy trinity of Jak & Daxter, Ratchet & Clank, and Sly Cooper, I have come to the conclusion that while the transition from relatively lightweight fare to more serious storytelling may appear spontaneous from a player’s perspective, it actually works best when this change plays out as if the developers had planned it from the beginning.

Some games are better suited for this kind of change, even if the developers didn’t necessarily plan to do it right away. Some game series feature characters who are well-rounded and well-established right from the start, making subsequent attempts at maturity easier to pull off. Others, however, are hampered in such attempts because their characters start off as too simplistic, and this puts the authors of the sequels in a terrible dilemma if they want to tell more mature stories. On the one hand, if they rewrite the characters so that they become more well-rounded, they run the risk of alienating audiences who have identified the characters’ simplicity as a fundamental aspect of their personalities; on the other hand, if they leave the characters as they are, they aren’t able to use the most effective tool writers have for telling mature stories.

Jak & Daxter: The Least Successful of the Three

Jak & Daxter was a series of action-platformers on the PS2 developed by Naughty Dog, the acclaimed studio responsible for Crash Bandicoot the generation before and Uncharted and The Last of Us the generation after. The first game in the series, Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy, was a sprightly, cartoonish, collect-a-thon platformer, with an inviting world populated by colorful characters, although they weren’t nearly as colorful as the color scheme used to bring this innocent-seeming world to life. The plot revolved around silent protagonist Jak trying to turn his best friend Daxter back into a human after he was comically transformed into a small, furry creature called an “ottsel” (a cross between an otter and a weasel).

Every time Jak and Daxter collect a Power Cell, the collectibles that drive the first game’s plot, they do a joyous little victory dance.

From those cheery, fanciful beginnings, the series took a pretty drastic departure in style for its sequel, Jak II. The sense of whiplash occurs in mere minutes, as the main characters from the last game open a trans-dimensional portal, encounter monsters that are considerably more foreboding than anything the first game produced, and then find themselves in the military-controlled Haven City, with Jak being arrested and subjected to torturous experiments for two years at the hands of the city’s dictatorial ruler, Baron Praxis. The opening cutscene ends with Jak, formerly a silent protagonist, escaping from his imprisonment and saying, in an angry, gravelly voice, “I’m gonna kill Praxis!” It was as if the writers wanted to violently disabuse players of the notion that they were playing kid stuff.

In Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy, Jak’s love interest is Keira, an enthusiastic “girl next door” who makes her entrance by chirpily offering Jak and Daxter advice to help them on their way.

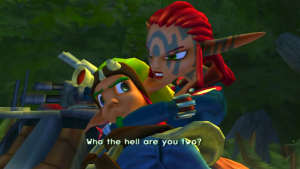

Jak’s second love interest, the lower-voiced, facially tattooed Ashelin, first appears in Jak II by holding a gun to Jak’s head.

This aggressive, unsubtle approach to maturity continued for the rest of the game. In addition to the simple punching and kicking featured in The Precursor Legacy, Jak II augmented Jak’s offensive move-set with several firearms; for several of the supporting characters, the default facial expression is a confrontational scowl; and the plot focuses on Jak and Daxter getting embroiled in a deadly war to defend Haven City from an invading army of monsters. This newfound grittiness was a far cry from the lighter, more innocent tone of The Precursor Legacy, and many of those who enjoyed the first game found the second one jarring, to say the least.

That said, this sudden change may have been justified, in a way. There wasn’t much of substance to expand on from the first game. None of the characters was well-rounded: as charming as they were at times, each of them had only a single personality trait, with some not even having that much development. None of the characters had clearly defined relationships with each other, with the possible exception of the antagonistic relationship between Daxter and his mentor, Samos the Green Sage. The plot was a simple good-vs.-evil story, and one that was rather decisively concluded at the end of the first game, at that. (There was some vague sequel bait in the game’s secret ending, but it didn’t foreshadow the attempted maturity or severe tonal shift in Jak II.)

The point is, it seems Naughty Dog decided they had to look elsewhere for their inspiration for Jak II. That’s all well and good. However, with Jak II’s mission-based game structure, gritty tone, and vehicle-stealing mechanic, it would seem that Naughty Dog made the very odd choice to use Grand Theft Auto as their inspiration. (I’m not sure the developers deliberately set out to copy from Rockstar Games, but the similarities can’t be ignored.) This meant that Jak II , as well as the similarly structured Jak 3, felt downright jarring when compared to the first game, but there was a more serious problem: these sequels were trying to make audiences feel for the characters without taking the time to develop them. They seemed to be aiming for simply having these emotional moments, thinking that this would in and of itself bestow maturity on their stories. They confused true maturity with a symptom of maturity. Actually, it wasn’t even that: they confused maturity with a result of a tool used to implement maturity.

Remember, well-rounded characters are just a way for stories to explore themes and ideas; it is the presence of these themes and ideas that defines a story’s maturity. What, then, are the themes explored by Jak II and Jak 3? As I write this, I’ll admit that despite owning these games and having played them several times, I’m having considerable difficulty stating any ideas the games explore. The closest thing I can think of is that perhaps they explore the theme of fatherhood, as Jak relies on a succession of older male authority figures throughout the series (Samos, Torn, Krew, Sig, and eventually Damas, who turns out to be his real father), but I think that’s a bit of a stretch. The Jak & Daxter sequels, in short, were attempting to be mature by aping features they misidentified as being the essence of maturity, while ignoring the fundamentals of significant themes and, more specifically, well-rounded characters.

There doesn’t appear to have been much attention devoted to character development in The Precursor Legacy, as I said. However, I think there was something else Naughty Dog could have done to move to more mature storytelling: concentrate on expanding or further exploring the first game’s world. Although the first game doesn’t have well-rounded characters, it does manage to provoke emotional reactions from players in another way: its world is so detailed that players may, at times, feel like they’re really there: exploring it, adventuring, and having fun. Maybe the sequel could have done what Silent Hill 2 did for Silent Hill: concentrated on the setting, replaced the cast of characters with more interesting ones, and told a different story that maintained the primary emotional draw of The Precursor Legacy… or, at least, they could have, if only they hadn’t named the series after its underdeveloped lead characters.

The first Jak & Daxter game pigeonholed the series in a way that its sequel rebelled against with every fiber of its being. Jak II bifurcated the series sharply between “light-hearted romp with a pair of pals” and “super-angsty, hardcore edginess.” Any hope of experiencing a gratifying, gradual ascent to more mature storytelling died before the gameplay of Jak II even began.

Ratchet & Clank: More Successful, But Still Fraught with Problems

In a way, it’s strange that Jak & Daxter took the sharp left turn it did, considering that another series, one that has an unusually close relationship to Jak & Daxter (that’s a discussion for another time), started out in a similarly unfortunate position, but managed to handle the transition more gracefully nevertheless.

The early Ratchet & Clank games didn’t have complex stories; much of the games’ creative focus went into gameplay and weapon design, as is exemplified by the cover art of the original PS2 game.

Ratchet & Clank is a series of kid-friendly 3D platformers/3rd-person shooters that started on the PS2, continued on the PS3, and still exists today with a reboot on the PS4 and a theatrically released movie. Like Jak & Daxter, the series started off as a comical, light-hearted romp through colorful environments, but eventually the games started showing signs of an attempt at greater maturity.

The Ratchet & Clank games on the PS2 were simplistic good-vs.-evil stories featuring a pair of buddies gallivanting across the galaxy and battling one-dimensional baddies. The series made a noticeable change to its M.O. with the Future trilogy on the PS3, with dense plots that involved (among other things) trans-dimensional teleportation, implied genocide, newly created backstory that was (presumably) designed to make players feel more emotionally connected to the characters, and the very unraveling of time itself.

Yes, truly, this is a character who’s ready to grapple with the near-extinction of his species.

However, as great as many fans and critics consider this game to be, its greatness came with a heavy cost. Unlike Naughty Dog, Ratchet & Clank developers Insomniac Games demonstrated that they recognized they would have to spend time transitioning to more complex storytelling, rather than starting it abruptly, in order to not have their new games feel like they belonged to a completely different series. It seems they also realized that, unfortunately, there wasn’t much to expand on from the original PS2 trilogy of the original Ratchet & Clank, Going Commando, and Up Your Arsenal. The character of Ratchet had very little personality in the original game, and he had even less personality in its two sequels. (I imagine this happened because someone at Insomniac realized that the character of Ratchet from the original game was a self-centered jerk.) Clank has always been an emotionless automaton, so he works as a foil to the more human Ratchet, but that doesn’t leave much room for character development. As a result of this, time needed to be spent adding the potential for maturity where there was none before, something that unfortunately took an entire game to accomplish.

Although it was well received at the time of its release, the series’s PS3 debut, Ratchet & Clank Future: Tools of Destruction, is in retrospect nothing more than setup for the emotional payoff of A Crack in Time, with little reason for players to enjoy it on its own terms. The game does have a plot of its own, but most of the significant events in the game were simply Ratchet and/or Clank discovering something that provided details about Ratchet’s past; very few of them related to the game’s purported plot revolving around a quest to dispatch its villain, Percival Tachyon. On that note: for a series that has produced such deliciously evil villains as Captain Qwark, Dr. Nefarious, Captain Slag, and Ultra Supreme Executive Chairman Drek, Percival Tachyon may be one of the least memorable villains the series has ever offered. Indeed, there was so little forward momentum in Tools of Destruction’s central plot that it was often easy to forget about Tachyon entirely. Much of Tools of Destruction is dedicated instead to explaining what happened to Ratchet’s species, the Lombaxes; why he’s the only one left; what happened to his father; and how Ratchet managed to survive. These concepts aren’t used to any kind of narrative effect until Ratchet meets Alister Azimuth, a long-lost fellow Lombax, in A Crack in Time. Going back to play just Tools of Destruction is like going back to the Harry Potter film series and only watching Deathly Hallows, Part 1: it’s not a full story in its own right, but rather an incomplete part of a greater whole, and one that becomes narratively useless to audiences once it’s done its job of establishing plot points for future reference.

Wait… who were you again?

Perhaps this use for Tools of Destruction as exposition would have been warranted if the Future trilogy had more clearly been distinct from the PS2 games, but there’s a great deal of content tying these newer games into the older ones. Supporting characters from the PS2 games return, including fan favorites like Captain Qwark, The Plumber, and Dr. Nefarious. References are made to the events of the previous games. Weapons available in the game are, in many cases, callbacks to weapons used in previous games. Because of the connections it makes to earlier games in the series, Tools of Destruction is clearly not the beginning of a wholly new series.

However, because Tools of Destruction makes Ratchet uses its abundance of new backstory to make Ratchet more well-rounded, it’s not an appropriate continuation of the old series, either. In the PS2 games, Ratchet and Clank weren’t particularly well-rounded, and while this did limit those games’ storytelling potential, it didn’t mean that changing courses mid-series was a good idea, either.

If multiple individual stories are to exist within the same series, there must be some thread connecting them that is present in all of them. Like Jak & Daxter, the Ratchet & Clank series is named after its two protagonists, so the obvious way to connect stories together in these series would be to make sure its characters were consistent across all such stories. That’s not to say consistent characters are strictly necessary for constructing series: going back to Silent Hill again, that’s a series that gets away with introducing a new protagonist in every installment because it’s made very clear that the focus, and the common element, is the setting rather than the characters. For series like Jak & Daxter and Ratchet & Clank, however, it is of particular importance that the characters remain consistent, and it is for this reason Tools of Destruction fails to properly continue its series. Ratchet and Clank were not well-rounded in their early games, but they had just enough personality to keep from being completely boring. In a way, the simplicity of the characters was a signature feature of the early Ratchet & Clank games, and this character-focused series had a responsibility to continue telling stories in a way that maintained this. Trying to make Ratchet more well-rounded at that point had the result of rather sharply distancing Tools of Destruction and its two sequels from the PS2 games.

In summation: the Ratchet & Clank series, while it does approach maturity more successfully than Jak & Daxter, has one glaring problem in that it, too, doesn’t work as a cohesive character piece. Tools of Destruction is emblematic of the point of separation between the earlier games and the later games, being neither the beginning of a new series nor a continuation of the series as it had been up until that point. It exists in a no man’s land in the middle and, unfortunately, leaves the series’s tonal consistency and overall continuity in a bit of a mess.

Sly Cooper: Increasingly Mature Video Game Storytelling Firing on All Cylinders

We’ve now seen two attempts at taking a series of video games aimed at children and making them more mature in their storytelling. One was an outright failure, with seemingly no attempt to make the transition feel natural at all. The other was more successful, but it still had to deal with the consequences of not adequately preparing for more mature storytelling early on. Now let’s take a look at a series that managed to become more mature in a way that felt natural and made some already excellent games even more enjoyable.

This cover art for Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus is very simple, much like the game’s plot; just going by this, one could be forgiven for mistaking its characters for mere cartoons.

Sly Cooper is a series I adore for a good many reasons: its voice acting, its dialogue, its gameplay, its visual design, and its music are all top-notch. Most importantly, however, I love its storytelling, including the seamless way in which it made the transition from simplistic storytelling in its first entry to more emotionally charged storytelling in later installments.

“Funny, but… here I am at the end, and suddenly, all I can think about is what a coward I’ve been towards Carmelita. I never took the next step…”

The first entry in the series, Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus, was a kid-friendly 3D platformer with stealth elements, featuring a likable cast of heroes infiltrating a succession of criminal hideouts overseen by comical, colorful villains. The plot was that old clichéd 3D platformer plot. You know the one: a dastardly villain has for some reason taken a bunch of MacGuffins and placed them in various areas that the hero(es) must explore in order to collect them all. In the case of this game specifically, that meant Sly had to infiltrate the hideouts of the members of a gang of criminals called The Fiendish Five in order to collect sections of the Thievius Raccoonus, a book written by his ancestors containing their accumulated wisdom and describing their innovative thieving techniques.

Changes came with the game’s sequel, Sly 2: Band of Thieves. It wasn’t considerably different in tone from the first game, but developers Sucker Punch did a great deal to differentiate Sly 2’s storytelling from that of its predecessor. For one thing, although the story structure was largely unchanged overall, the way in which each individual chapter played out was entirely different. Instead of simply completing a collection of linear platforming challenges and minigames, many of which had little context within the story, Sly 2’s chapters each play out as miniature heists, with each chunk of gameplay serving as one bit of preparation that would be integral in executing the heist in the final mission within that chapter. Also, Sly 2 wasn’t as repetitive, formulaic, and predictable as Sly 1: at times, plans would change, things would go awry, and villains would (gasp!) escape… if only until the following chapter.

However, the most significant change, in my opinion, was that Sly 2 featured cutscenes and exchanges of dialogue that used the characters’ emotions to further the story. This is important in establishing maturity for two reasons.

- Using the characters’ emotions in the story can function as an indicator of how well-rounded the characters are: if audiences respond to such moments with empathy, then that means the characters are so well-rounded that they seem similar enough to real human beings to provoke real emotional reactions for people who don’t even really exist.

- When audiences do feel connected to the characters, using the characters’ emotions is an effective tool for exploring mature themes and ideas; the human mind is largely driven by emotion, so using an emotional connection to communicate themes and ideas is an effective way of getting audiences to understand these themes and ideas at a fundamental level.

Jak & Daxter and Ratchet & Clank also used their character’s emotions to try to further their stories, but these moments feel odd and out of place in those series, while they feel right at home in Sly Cooper, despite the first games of all three series not having any such moments. Why is that?

Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus uses strikingly drawn cutscenes, usually narrated by Sly, to provide its important exposition. This one in particular details how Sly met future colleagues Murray and Bentley at an orphanage as children.

This puts Sly Cooper head and shoulders above its peers in how well prepared it was to tell mature stories. What do we know about the characters in Ratchet & Clank? By the end of that game, we know that Ratchet is rather self-centered, that Ratchet had never left his home planet before the beginning of the game, that Clank is a calmly logical robot, that Ratchet used to idolize Captain Qwark until his betrayal, and that Ratchet and Clank have become friends over the course of their first adventure. By the end of Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy, we know even less than that: we know that Jak and Daxter are friends, that they don’t have much respect for the rules, that Daxter is a smartass, and that Jak has a crush on Samos’s daughter, Keira.

In Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus, we learn that Sly, Bentley, and Murray have been very close friends ever since they grew up together in the same orphanage; that they’ve been working as a team stealing things since their childhoods; that Sly is more carefree and confident than nervous planner Bentley; that Sly is descended from a long line of master thieves; that he was about to inherit his family’s account of their storied history and thieving techniques, the Thievius Raccoonus, when a gang of criminals stole the book and killed his parents, providing Sly’s motivation for this game; and, finally, that Sly has a playfully amorous relationship with Carmelita Fox, an agent of the law who’s determined to put him behind bars — and we learn all of this before the end of the prologue! Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus establishes more in its opening than Ratchet & Clank and Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy do in the entirety of their stories! Although the first Sly Cooper game didn’t directly present any moments designed to make gamers feel for its characters, its diligent approach to character exposition meant there was a sturdy foundation upon which sequels could do precisely that.

“It was all so strange. The focus of all our schemes had been stolen from us. Our Clockwerk parts were gone. Looking around the inside of the battery, I knew we all felt it: failure. I was twitchy and ready for action, any action. Bentley tried to make some sense of the situation by drawing up meaningless plans. But Murray, Murray took it the worst. He just sat there, sobbing, while the team van floated away over the horizon. That van was his life. I knew I’d have to find a way to make it up to him.”

That’s not all Sly 1 did, however: in addition to ensuring its characters were well-rounded, it also established the beginnings of themes and ideas that could easily be expanded on it sequels. For example, consider that at no point in Sly 1 is the Cooper Gang in real danger of failing their mission. They face challenges and have setbacks, to be sure, and individual members are in peril at times, but the team as a whole is essentially unstoppable. This, along with Sly’s consistently high confidence level, communicates to players that the Cooper Gang is exceptionally competent. This image is then upturned to great effect near the end of Sly 2 when, after having lost everything they spent the entire game working for, Sly, Bentley, and Murray have no option but to wait to be transported to the final boss’s lair. This is the first time we see them at their lowest, utterly powerless as they are shuffled along toward a disaster they were trying to prevent. There is nothing they can do but wallow in their own failure, and Sly’s narration in this scene makes it achingly clear that this is not something they’re accustomed to, and that none of them are taking it well. It’s absolutely heartbreaking.

As another example, family honor is a recurring theme throughout the Sly Cooper series, and the first game establishes it well. Sly’s backstory involves him seeing his parents murdered in front of him. He’s on a mission to retrieve the pages of a book written by his ancestors. With every recovered section of the Thievius Raccoonus, Sly learns a new move/technique, weaving this theme into the gameplay itself. All of this is capitalized on in future games. Sly 3: Honor Among Thieves ends with Sly entering his family’s vault of treasures, using techniques invented by various ancestors of his to progress deeper into the vault, and learning a new technique invented by his father in order to defeat that game’s final boss. The entire premise of Sly Cooper: Thieves in Time sees the Cooper Gang traveling to various points in history and meeting a handful of Sly’s ancestors.

Those are just two examples of the many ways in which Sly Cooper uses setup and payoff to tell its stories and communicate its ideas, but the series is so rich with character that I found many others. (Maybe I could delve into Sly Cooper’s depths of plot in a later article…) Most, if not all, of these developments were set up in earlier games in the series than the payoff, ensuring that every such event never felt out-of-place with the rest of the series. None of the games that did go for the emotional jugular felt too dissimilar from prior games because nearly every emotional moment could be traced back to those prior games, including several in the very first, less emotionally mature, game. Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus takes time to establish its characters, their backgrounds, their motivations, and their relationships to one another.

Conclusion

In a discussion about Jak 3, YouTuber SuperButterBuns summed up her opinion on the game by saying, “[T]he Jak series is very close to people’s hearts and childhood, and watching a game grow up with you is always interesting to witness.” Although I don’t agree with her tacit implication that this phenomenon applies to Jak & Daxter specifically all that well, I can certainly appreciate that seeing a beloved video game series from your childhood start to show more depth and maturity as you start craving such things would be very gratifying. Not only that, but it could help video games, like comic books and animation before them, shake off the stigma of being a disposable children’s medium by subverting people’s expectations.

Video games have already been attempting this for some time now, as exemplified by the PS2 3D platformer holy trinity. The Jak & Daxter series made the mistake of doing it too abruptly. Although the sequels weren’t entirely disconnected from the original game, it became very clear to gamers right at the start of Jak II that the series would be going in a different direction, effectively hitting the reset button and prompting many fans of the series to consider Jak II to be the proper start of the series, ignoring the first game altogether. Ratchet & Clank was better about making its newfound maturity more apropos, but because its characters weren’t well-rounded early on, the series had to sacrifice its PS3 debut in order to set up the emotional depth of later entries, leaving a dead zone of relatively little important plot development in the middle of the series. Sly Cooper is a prime example of maturing into emotional storytelling well. It didn’t throw everything away and start from scratch, like Jak & Daxter did, and its practice of thoroughly setting up its characters early allowed sequels to expand on its characters expediently, unlike Ratchet & Clank.

These examples illustrate that making a series more mature means more than simply grafting mature elements on a series originally made for children. In order to properly make a video game series more mature, one needs to ensure that its new, more mature elements can be reasonably traced back to earlier games in order for the transition to feel natural and not come across as forced, and it’s best to do this early in order to avoid problems. A certain degree of retrospection is required in order to truly elevate earlier entries in a series, and using the trusted storytelling tool of well-rounded characters early on can make this retrospection more amenable to exploring themes and ideas in order to obtain true narrative maturity.

2 Comments

Josh · March 12, 2018 at 3:53 am

Peter I just want you to know that this is an exceptional article. I stumbled upon this after looking up gameplay for sly Cooper and the thievius raccoonus and literally stopped playing the game and read this article the whole way through and I agree with all of your points and totally appreciate this article as it articulates perfectly the themes and maturity journeys each of these games made. Great read!!

Peter Finn · March 17, 2018 at 6:27 pm

Whoa, thanks, man! That means a lot to me!

Which of the three series is your favorite?