A couple months ago, I wrote an article about why I’m glad the Dark Souls series could never continue beyond Dark Souls III’s final DLC, The Ringed City. The reason, ultimately, was that the Dark Souls series, on my view, is a masterfully designed work of closed storytelling: the creation of a story where no aspect of the plot is left unresolved, and so there is nothing about the story to resolve in a later story. This contrasts with open storytelling: the creation of stories where aspects of the plot are left unresolved, such that these aspects of the plot can instead be resolved in a different story. I was especially grateful to Dark Souls in this regard because, as I see it, open storytelling is only becoming more and more prevalent and pernicious, both in video games and in storytelling media more generally: it’s a tactic to string people along by only giving them part of a complete story in any given game, novel, or movie, all while pretending to give them a complete story.

At the end of that article on Dark Souls, I remarked that the majority of games I personally analyze on With a Terrible Fate are cases of closed storytelling, the reason being that the tendency of closed stories to describe an entire, self-contained universe gels very naturally with my metaphysics-first approach to the analysis of video-game storytelling. As other examples of such storytelling, I mentioned:

I thought about mentioning Dishonored, too. It would have made sense to mention it: I’ve written about it extensively, and I first played it (upon its original launch date) at a formative time when I was just beginning to take the storytelling value of video games seriously. And, frankly, had I written this article about Dark Souls a year ago (in a world where the entire Dark Souls series had been released at that point), I would have included Dishonored on that list with Xenoblade, BioShock, and Bloodborne.

But Dishonored 2 was published in the past year, and it transformed my understanding of the first game—and not for the better.

Double the avatars promised double the value in Dishonored 2… I was led to believe.

I played Dishonored 2 eagerly as soon as it was released, but I haven’t written anything about it before now. That’s because, while I certainly enjoyed playing the game, something about it never sat quite right with me—but for the longest time, I couldn’t tell what it was.

Now, however, I think my analysis of Dark Souls has provided the groundwork to articulate what always troubled me about Dishonored 2. In a single sentence: Dishonored 2 turned the original Dishonored from a closed story into an open story.

The potential for a sequel to “undo” an originally closed story by making it open is something I didn’t at all address in my article on Dark Souls, but I think it’s one of the most pernicious dangers of open storytelling because it can infect a once-closed story with all the problems to which open storytelling is susceptible. So, I want to use this article as an opportunity to articulate this danger of “opening closed stories,” while also explaining why Dishonored 2 does deep storytelling violence to the original Dishonored.

I first outline why the original Dishonored was a rich and unusual case of closed storytelling. Then, I show how the story of Dishonored 2 reframes that story in such a way as to make it open rather than closed. Finally, I step back to consider the broader ramifications of the opening of closed stories, and what can be done about it.

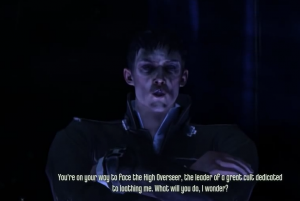

“What will you do, I wonder?”

It’s easy to suppose that Dishonored is a simple revenge story. Here are three reasons for thinking so:

- The plot centers on finding and getting even with various people who have conspired against and betrayed Corvo Attano, the Royal Protector and the player’s avatar.

- It’s impossible to show mercy to your enemies: you can either kill them or find non-lethal ways to dispose of them that are virtually all worse than mere execution (e.g., cutting out two brothers’ tongues and shipping them away to work in mines for the rest of their lives, rendering a socialite unconscious and letting her stalker spirit her away, never to be heard from again).

- The game’s tagline is literally “Revenge solves everything.”

Sure, you can get revenge for Corvo—that’s not the point, though.

No doubt, revenge looms large in Dishonored. But to suppose that this is all that the game is about—or, indeed, even what it’s centrally about—is to ignore the broader context in which Corvo’s revenge mission is situated.

Corvo’s story is observed constantly, not just by the player, but also by The Outsider: an otherworldly, god-like figure who exists beyond Corvo’s time and place in an ethereal, formless realm called “The Void.” The Outsider, looking to all who see him like an ordinary man in street clothes, has one goal: he wants to see people make interesting choices through a combination of intense motivation and intense power. To achieve this, he seeks out people with intense motivation—people like Corvo, who has been framed for murdering the Empress, whom he was duty-bound to protect and with whom he sired a child—and gives them intense power in the form of The Outsider’s Mark—a brand that links the bearer to The Void and gives them occult powers, like manipulation of time and possession of other living beings.

In Dishonored, The Outsider is presented as an otherwordly observer—much like the player.

What’s compelling about The Outsider is that he has no stake in the events of mortals: he doesn’t care what people do with his Mark, so long as they do interesting things worth watching, and he only abandons people (like the assassin Daud) when they become boring. In this way, The Outsider is in a position very closely akin to the player of Dishonored: the player picks up the controller of Dishonored and is presented with a fictional world where their avatar can make a variety of choices. The player, like The Outsider, has no deep, personal stake in the events of this world: since it’s all fictional, there are no real-world consequences for the player to face for Corvo’s actions, and the player can always simply turn the game off if she no longer finds it interesting. The player’s only directive is to have the one vested with the “power” of her influence—i.e. the avatar, Corvo—make interesting choices so that the story he tells is worthwhile, and this makes the player perfectly analogous to The Outsider.

This framing of Dishonored as a story designed to interest the player and The Outsider is the reason why it’s wrong to say the story of Dishonored is “about revenge”: at its core, Dishonored is just about the player playing with choices and their consequences in order to entertain herself and The Outsider. This explains why the game’s tutorial narration is so upfront in explicitly telling the player about the game’s choice system and the eventual consequences of making different kinds of choices. This isn’t just to teach the player how to play the game: it’s giving the player this information because the entire narrative of the game is about the player being knowledgeable of the choices available to her, choosing a particular choice, and seeing what happens.

This is why the game ends with The Outsider narrating the future consequences of Corvo’s choices, rather than merely ending with something like a final scene of Corvo coping with the consequences of his actions. Regardless of which particular ending the player and Corvo achieve, The Outsider concludes the game by emphasizing illustrating the impact of Corvo’s choices, tacitly affirming that Corvo succeeded at being interesting.

Reinforcing his ultimate goal of being entertained, The Outsider tells Corvo that he’s had “a lovely time” in the ending where Corvo allows Emily to die.

The fact that the game’s choice structure is explicated to the player also invites the player to replay the game and make different choices. And the game’s special kind of storytelling makes the player want to replay and make different choices: the story is built in such a way that virtually the entire meaning of the narrative is grounded in the player’s desire to simply play around with the game and see what happens.

What I mean by that is this: there are some games, like Mass Effect, where the player is aware from the beginning that she has license to make a wide variety of choices throughout the game, yet she still might not want to replay and make different choices. That’s because, in a game like Mass Effect, the player’s choices are defining a particular character (the avatar) with which other characters have relationships that evolve based on the player’s choices. Players may shrink from the option to replay Mass Effect and make different choices simply because their first choices led them to create a certain version of their avatar, Shepard, with which they came to associate themselves. We sympathize with fictional characters all the time, so it’s only natural that we wouldn’t want to replay the same game and turn a character with which we’ve come to identify as (for example) an honor-bound rule-follower into an unlikable rebel: to do so feels disingenuous to some players because it nullifies the relationships and personality their avatar developed during their first time through the game.

Once you’ve cultivated a certain kind of Shepard, it’s challenging to decide to replay the game.

But Dishonored isn’t like that, because Corvo is never really given a personality in the sense of having a free-standing set of dispositions, emotions, and beliefs with which the player can sympathize and engage. Corvo is represented in the game as a silent protagonist, and players always see the game’s world through his eyes, rather than seeing him from a third-person perspective. The peculiar consequence of this—especially in the context of The Outsider framing Corvo’s adventure—is that it’s very hard to see Corvo as a fully fleshed-out character. Instead, Corvo is more akin to a mere set of choices that the player makes. No character—not even Emily, Corvo’s daughter—has a deep interpersonal relationship with Corvo: they merely view the choices he’s made within the game favorably or negatively.

Even Corvo’s daughter only relates to him by reacting to his choices.

This might seem like a minor point to be emphasizing, but these features of Corvo’s relationships with other characters and the player have a marked difference on how the player engages with the game: because the player is simply seeing how the world and other characters react to Corvo’s choices, rather than constructing a robust character to which she and the game’s characters are intimately connected, it is remarkably easy for the player to identify with The Outsider’s curiosity and desire to see interesting stories play out based on Corvo’s choices. The player can spare every person in the game, then promptly start a new game and slaughter everyone instead. The dual pillars of (1) The Outsider—an in-game, curious-yet-disinterested analogue to the player—and (2) Corvo—a character that makes high-impact choices without ever developing interpersonal connections or personality—buttress Dishonored’s unusual status as a game whose narrative is actually about experimenting with a wide variety of choices for mere entertainment.

I think that this theme of experimenting with choices for mere entertainment is what make Dishonored so satisfyingly simple in its storytelling. No matter how much you might try to apply deeper, more “poignant” themes to the game, the game will steadfastly resist you. For instance: at this juncture, you might concede that the game is all about choice, yet argue that this leads the player to deeply reflect on the value and consequences of their choices. But Dishonored isn’t Undertale, where characters explicitly remember what the player did, even across multiple playthroughs, and judge her for it. In fact, it’s telling that The Outsider is antithetical to that motif of judging players for their choices. For it’s evident in Dishonored that The Outsider exists beyond space and time as the game’s characters understand it, yet he doesn’t pause to reflect on choices that some earlier version of Corvo made in some previous playthrough of the game. His curiosity is fresh with every fresh playthrough of the game, further reinforcing that the player ought to simply have fun and make whatever choices, out of interest in what will happen rather than fear of what will happen.

The Outsider’s disinterested curiosity is best captured by his rhetorical question to Corvo: “What will you do, I wonder?”

So, what we have in Dishonored is an example of closed storytelling that’s driven by curiosity. A disinterested god, alongside a similarly disinterested player, has taken an interest in a particular scenario—the framing of the Empress’s Royal Protector for her murder—and wants to be entertained by seeing what consequences come from that scenario. He doesn’t care about the history of the world before the scenario, nor about what happens after the consequences of that scenario have played out: he only cares about the self-contained set of choices that Corvo makes in response to being framed, and wants to see the consequences of all Corvo’s possible choices, along with the player, to fully sate his curiosity. The game is simple, but not in a boring way: it’s simple because its most foundational narrative framing gives the player absolute permission to freely explore Corvo’s possible actions, without caring in any serious way about their consequences.

What He Did: No Wonder

When I first played Dishonored 2, I was troubled by an apparently disparate set of changes that had been made from the original.

- Now, Corvo had a voice

- Now, there was a “true ending” to Dishonored, from which the sequel’s story followed

- Now, The Outsider and The Void apparently had a history

I don’t think there’s any a priori reason why any one of these changes is damaging to a game’s storytelling. Games can still tell stories well when their avatar is first-person (i.e. the player sees the world through their eyes) and speaks to other characters (e.g., the new Deus Ex games); they can still tell good stories when their sequel elevates one possible ending into the status of the “official ending” leading to other games (e.g., NieR: Automata); they can quite obviously still tell good stories when they give characters back-stories.

But the closed/open storytelling paradigm explains why, for Dishonored, the conjunction of these changes was devastating to the series’ storytelling: the changes reframed the first game’s story as an open story, rather than a closed story.

Recall that the two pillars supporting Dishonored’s closed storytelling are The Outsider’s status as a disinterested figure outside of space and time, and Corvo’s status as an agent with choices but no personality. Dishonored 2 topples each of these pillars in turn.

Pillar 1: The Outsider. Whereas The Outsider was little more than a curious observer in Dishonored, Dishonored 2 furnishes him with a full backstory of how, once-human, he was ritualistically sacrificed to “merge” with The Void. Not only that, but Dishonored 2′s main villain—the witch Delilah, promoted from DLC antagonist to principal enemy in a main game—is revealed to have become “part of The Outsider” when the assassin Daud banished her to The Void (another possible ending—this time, in Dishonored’s DLC—transfigured into a “true ending”).

“This is where it happened…”

“This is where they killed the first Dishonored.“

Maybe you take this to be an interesting story; if I considered it on its own terms, I might find it interesting, too. The problem, however, isn’t in whether or not it’s interesting: it’s in the fact that it’s transformed The Outsider—a character who, in Dishonored, was a nondescript, extra-dimensional observer who simply liked to give mortals power and enjoy the choices they made—into someone with relationships and history in that world he was previously just observing. Because Dishonored 2 is presented as a direct sequel, contiguous with the world and events of Dishonored, this implies that The Outsider in Dishonored also had this kind of history in the world we thought he was just observing.

So the first pillar of Dishonored’s closed storytelling has fallen: given the information provided about The Outsider in Dishonored 2, it’s no longer the case in Dishonored that a disinterested observer is merely curious about what will happen in a world separate from his own. Instead, The Outsider is a character like any other, with a history that extends to both before and after the events of Dishonored.

Pillar 2: Corvo. With the simple addition of speech, Corvo has also been transformed. He talks to himself, he has conversations with other characters—put simply, he now has a personality that evolves based on the choices that the player makes. He wrestles with his options, he rationalizes his choices—and, because the game follows up on a specific ending of Dishonored (an ending in which he successfully saved Emily), he’s a character with a specific history based on only some of the possible choices available to the player in Dishonored.

Corvo showing off his full-fledged character with Emily.

Because Corvo has now been fleshed out into a robust character, we can’t see him as a mere conduit for player choices anymore: he’s become more like Shepard, a character for which the player shapes an identity throughout the game. And some of that identity has already been established at the start of Dishonored 2: his close relationship with Emily. This means that, in the narrative of Dishonored, not all choices available to the player have equal narrative meaning: some lead to the “established narrative” of Dishonored 2, and others don’t. Even if you don’t want to identify the former set of endings as endings that are somehow more valuable in virtue of leading to the game’s sequel, it’s clear that there now are two distinct kinds of ending to the first game’s narrative, differentiated by their place in the overall series. So we can no longer say that the story of Dishonored is a story about making whatever choices you like, merely for your entertainment—now, there’s an additional kind of meaning to the outcomes of the game.

And so the second pillar falls. Dishonored 2’s representation of Corvo, The Outsider, and the history of their world has recast Dishonored as a single episode in a continuous, singular history, rather than a self-contained exploration of choice and curiosity. What was once a closed story has thus become open, simply in virtue of its sequel elaborating on its characters and world in a way that directly nullifies the features of the original story that made it closed.

Maybe you’ll object at this point that this was inevitable as soon as the developers decided to make a Dishonored 2: after all, any kind of game that follows up on the story of Dishonored will have to choose some particular ending to follow up on, and it’s quite natural to want to elaborate on the histories of your main characters, such as Corvo and The Outsider.

It certainly wasn’t inevitable, though. Consider the following kind of sequel as a counterexample: The Outsider fixes his attention on a character that is completely unrelated to the people and events of Dishonored, gives them his Mark, and watches to see what they’ll do. This game, like Dishonored, could easily focus merely on making choices for one’s own entertainment, without having any bearing on the events of meaning of Dishonored. There’s no requirement that a sequel to a story follow up on the plot of the original: this game would be a “rightful sequel” to Dishonored in virtue of featuring the same framework of The Outsider being curious about an interesting character, and it could feature the same choice mechanics to boot. Think of a series like Silent Hill, the entries in which are unified mostly by a single location (Silent Hill); or think of Black Mirror, where episodes are unified by a single theme (unsettling technological phenomena). There are many ways to continue a story without merely extending the chain of events that constitute the original story’s plot; if the developers had focused on instead extending Dishonored’s central theme of making choices for one’s entertainment, they could have preserved the closed storytelling that so artfully tied that first game together.

Silent Hill is a series strung together by continuity of place, much more so than continuity of events.

Instead, they infected the original game with the kind of open storytelling that baits people into buying more and more game content because they weren’t given a full story in the first place. They weren’t especially subtle about this, either: an audio recording that you can find in the game has Billie Lurk explicitly asking, “Where is Daud?”

You won’t find the answer in the game—but you’ll surely find it in the franchise to come.

Final Thoughts: The Villainy of Retconning

What can this tragedy of Dishonored 2 teach us about storytelling more generally, and how can we prevent it? I think the most pressing lessons are the dangers of retconning, and the need to treat authorial intent skeptically as a result.

“Retconning” is short for “retroactive continuity,” and is typically used to describe a kind of authorial parlor trick: an author will write a later part of the series to retroactively alter an earlier part of the series, in order to seem justified in telling a story that would otherwise contradict the continuity of their series. For example, the TV show Dallas famously killed off a character, Bobby Ewing, one season, and then, in the following season, made it the case that this death was actually just a dream, allowing them to “revive” the character in the show. This is the standard example of retconning.

The legendary Dallas retcon: waking up from a season-long bad dream.

Retconning, I think, is typically an invalid type of storytelling that supposes authors have the authority, at any point in telling a story, to “rewrite” early portions of the story through dei ex machina. If it’s not coherent with the rest of Dallas’ fictional world that Bobby Ewing’s death was simply a dream—where “coherence” is the extent to which a story’s characters, events, and other constituents related to each other with a plausible sort of fiction-internal logic—then the authors making it the case that it was a dream just introduces incoherence into the fictional world. Even the authors of a story are at the mercy of their fiction’s coherence, but retconning typically ignores coherence and simply asks audiences to let the authors cheat in their storytelling, with the promise that a better story will subsequently follow as a result of this cheating.

Dishonored 2, however, shows us that there is a type of legitimate, non-cheating, and insidious kind of retconning available to authors: they can write sequels that change the overall framing of the previous story’s events, rather than changing the events themselves. Dishonored as an open story is just as coherent as Dishonored as a closed story: all that’s really changed is that the story is now framed as part of a larger, unified storyline, rather than as a self-contained exploration of choice. As far as I can tell, this just isn’t illegitimate in the way that the Dallas example is: although the structure of Dishonored, taken on its own, presents experimentation with choice for entertainment as its primary, unifying theme, there’s nothing incoherent about using a sequel to instead highlight different themes and aspects of the characters in the first game. Dallas, on the other hand, actually rewrote events in its story through retconning: events best understood as actual were erased and replaced with corresponding dream-events. Dallas challenged its internal logic by so radically modifying the basic events constituting its plot, but Dishonored 2 just changed how players were meant to understand the narrative of Dishonored, internal logic and all.

We should be extremely worried about this kind of retconning, though, because it legitimizes the use of a sequel to retcon a closed story into an open story, as is the case with Dishonored. Why is this so dangerous? I’ve already said that open storytelling is great for baiting players into buying more games, because it promises them a full story but only gives them part of one. With this new retconning possibility on the table, something even more dangerous comes into focus: it seems that developers can give players a closed story—like Dishonored—that they can fall in love with and appreciate fully in virtue of that closed storytelling. Then, with players sold on the value of that game, the developers can make a sequel—like Dishonored 2—that retcons the first game into an open story, one part of a potentially infinite series. And just like that, the developers have performed a bait-and-switch that have gotten players hooked on a franchise of open storytelling.

Pictured: Umbrella Corporation.

Yikes, that’s depressing. What can we do?

I don’t have a great answer, but I have a suggestion. We’re tempted and pressured to think that authors of a story have full license over determining what’s true in the world of that story, even after they’ve published it and sent it off into the world. We listen to what they say about characters’ backstories on Twitter; we scour interviews, hoping they’ll drop secrets about the story’s world that weren’t revealed before; we play sequels to find out what happens next in the original story.

But we needn’t give authors this kind of full license. Once a story like Dishonored is completed and sent off into the world, it exists as a free-standing narrative object. The developers can say what they had in mind about The Outsider’s backstory, but that backstory doesn’t thereby become part of Dishonored’s story any more than your own personal speculation about The Outsider’s backstory is part of Dishonored’s story. The same principle, I think, applies to sequels that are released for stories, although it’s a bit harder to subscribe to the principle in that case. When developers release a sequel to a game, they’re telling a new story: they might see the new story as the one, true extension of the original game’s story, but that doesn’t make it the case that the first game is now just the first part of a larger story that extends to another game. The story of Dishonored remains a free-standing narrative object even in the wake of Dishonored 2, and we are only obligated to reframe it as an open story if we are analyzing it in the context of Dishonored 2.

If a story is open from the get-go—especially if it ends with “To Be Continued,” or some equivalent—then it’s less plausible that this principle would be used, but that’s only because you wouldn’t want to analyze the story on its own terms: it’s represented through-and-through as Part I of a larger story, and so it would probably be fruitless to ignore its sequel when you’re analyzing it. But when you’re considering a closed story like Dishonored that was subsequently given a sequel, you have a plausible, theoretically defensible choice: you can analyze it as a story on its own terms, or as part of the broader series.

So Dishonored 2 teaches us that developers have an insidious storytelling sleight-of-hand up their sleeves, allowing them to change closed stories into open stories. But it shows us that, as consumers of stories, we have a choice, even if it’s challenging to abide by it: we can politely decline the option to integrate the story’s sequel into our understanding of the original.