Dark Souls mastermind Hidetaka Miyazaki has been clear that, for him, Dark Souls III and its DLC marks the end of the series. In reality, though, you don’t need his confirmation to know this: the structure of the Dark Souls trilogy makes it virtually impossible that any Dark Souls IV could ever be added to the series in a logical and compelling way.

I’ve been missing the Dark Souls series a lot over the last few months. I’ve written before about the value of the games’ storytelling and its unusual ability to justify the existence of its DLC; few other series in recent memories have had such a marked impact on how people think about the artistic and storytelling potential of video games.

But I’ve come to believe that it’s a really good thing to miss Dark Souls and know that it’s not coming back: this is a symptom of the fact that the Dark Souls series told its story in a special and powerful way that’s becoming increasingly rare in video-game storytelling—and in storytelling more generally. In this article, I want to define this kind of storytelling, which I call closed storytelling, and contrast it with the less compelling open storytelling that is running rampant in video games today. Ultimately, I contend that closed storytelling is why it’s a good thing that Dark Souls could never continue as a series, though we’ll see that this is far from a death knell for the impact of the series on modern gaming.

Open Storytelling: The Problem of Inconclusiveness

“What happened next?”

If you’re telling a story well, your audience will always have this question on their mind: they’ll be invested in the story’s plot and want to know the whole story. But there’s a contaminant challenge that arises in crafting a story: how do you get people to stop asking “What happened next?” when your story reaches its conclusion?

A good story, you might think, concludes in such a way that the overall tension of the plot, development arcs of the various characters, and so on, have resolved, where a resolution entails that the person engaging the story is recognizes that its events all hang together in a cohesive way, and therefore isn’t left with a desire to know about whatever events came after the end of the story.

Intuitive as this seems, it’s actually bizarre that we expect stories to work this way: in general, after all, time always keeps moving forward, and there are always more events happening. So, in principle, there usually should be an answer to the question “What happened next?” at the end of a story. Storytellers, then, have the challenge of getting people to simply not care about what happens to their story’s characters after the story ends.

But of course, not everyone sees this as a problem to solve: many instead see it as an invitation to produce an endless lineage of sequels, constantly answering the question of “What happened next” in their stories. This is J.K. Rowling with the Harry Potter series and its spinoffs; this is the industry of serialized television storytelling; this is the Legend of Zelda series.

Writers who tell stories like this are engaged in what I call open storytelling: the creation of stories where aspects of the plot are left unresolved, such that these aspects of the plot can instead be resolved in a different story.

Open storytelling isn’t necessarily bad storytelling. As I said, in the majority of stories, it’s assumed that time and events exist both before the story’s chronological beginning and after its chronological end. So there are always ways to extend the scope of a story by telling another story in that same fictional world, even if the original story had a perfectly fine resolution at its conclusion.

The Legend of Zelda is an example of a series that uses open storytelling extremely effectively. Because most of its games follow the adventures of various incarnations of the same characters—principally the hero, Link, the princess, Zelda, and the villain, Ganondorf—at various points in history across multiple possible timelines, it is easy to endlessly expand the series by simply telling the same classic Zelda story of heroism at a new point in the overall Zelda timeline. This formula for storytelling links the various stories together by having each game’s world reflect the impact of events that happened in games that preceded it in the timeline, while the characters’ development and plot are (typically) fairly self-contained for each game. This is why it’s so easy for a newcomer to pick up and appreciate virtually any Zelda game, while a veteran can also play every single game and appreciate the series as a single work of art: the connections between the games, crucial though they are to understanding the overall arc of the Zelda universe, are inessential to understanding and appreciating any single Zelda story.

The many incarnations of Link across Zelda‘s open stories.

But there is an increasingly popular dark side to open storytelling: this dark side is what happens when games tell stories that fail to resolve certain elements that are centrally important to the story, with the promise of resolving these elements in a coming sequel. When storytellers do this, they effectively sell you an incomplete story: the promised resolution of themes, character, and plot that drives all storytelling isn’t delivered.

The Wachowski siblings’ Matrix trilogy is a vivid example of this. They wrote the second and third entries in the trilogy, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, as a single script, and then simply split it down the middle in order to make these two movies. The result is that both Reloaded and Revolutions are exactly what you’d expect: half of one complete story.

The second and third Matrix movies were literally a single script split into two “stories.”

This is open storytelling at its worst: storytellers tear their story in two, or otherwise surgically remove crucial parts of the story, only to deliver that content in a “sequel.” But if a good, Zelda-like sequel is one that simply tells another full story that follows up on an original full story, it’s crucial to note that storytellers of this Wachowski kind aren’t even offering true sequels: they’re splitting one story into multiple installments and pretending that each installment is a complete story. But story requires a complete developmental trajectory for its characters, where people can see the story and recognize how its pieces fit together coherently with an internal logic that articulates a clear message. If a story has this kind of internal logic, where each of its elements serves its overall message in a coherent and essential way, then excising one of those elements will necessarily render the story incomplete. Thus we need to recognize “stories” like The Matrix Reloaded and Revolutions for what they are: a single story, masquerading as multiple stories.

One point of clarification before we continue: a story can be complete without definitively answering every question someone has about its plot, even if these questions are about central aspects of the plot. There is probably no way to be sure from watching Inception whether the main character, Cobb, is in a dream or the real world at the end of the movie, but that doesn’t make Inception an incomplete story: the story has still resolved, because this final ambiguity between dream and reality is one of the central themes that the story represents. Put differently: rather than promising that we’ll find out Cobb’s fate in “Inception 2,” the end of Inception promises that we’ll never know what Cobb’s fate truly is. Stories can be about this kind of ambiguity while still resolving perfectly well; the problem arises only when the story fails to have whatever kind of resolution its internal logic mandates.

The crucial ambiguity of the spinning top at the end of Inception doesn’t count as poor open storytelling.

In terms of the production of stories, it’s obvious why this bad kind of open storytelling is running rampant: it’s a very easy and effective money grab. Why would you only sell someone a single novel, or film, or video game, when you could sell them two instead? Open storytelling is a diabolically effective way to ensure that people will buy two instead of one: if you mislead people into thinking that you’re selling them a full story, and then they find at the end of that first “story” that the story is actually incomplete, they’ll feel as if they have to buy the second “story” just because of the time they’ve already invested: they need the resolution that they were denied in the first place.

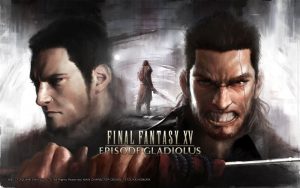

This is how you end up with epic games whose entire plots end with a literal “To be continued” screen, like Final Fantasy XIII-2. It’s how you end up with games that have had their innards ripped out and repackaged as DLC, like Final Fantasy XV , in which a character, Gladiolus, disappears without explanation, only to reappear later, also without explanation. Want to know where he was? Play the DLC.

Square Enix surgically extracted part of Final Fantasy XV‘s story and resold as a “supplemental” story.

For all the problems open storytelling already has generally, it’s qualitatively worse when applied to video games. Why is this so? As I argued at length in my article about why Final Fantasy VII doesn’t make sense as a multi-game remake, video games are special because they represent entire universes that the player can influence and alter. When games split their narrative across multiple games, this structure of causal influence is disrupted: the set of all choices that the player has made to change the world of the first game don’t transmit with perfect fidelity to the second game (this is true even of series like Mass Effect), and it also simply isn’t coherent to suppose that two games—each with their own story, their own world, and their own set of causal relations—can be causally interrelated in the direct and intimate way that would be required to stretch a single narrative across multiple games (something that I discuss much more granularly in the FFVII article I mentioned above).

So open storytelling isn’t just dangerous in virtue of giving developers an excuse to trick you into spending more money and buying more games in order to get a single, complete story: it’s also dangerous because it can render the unresolved stories of games incoherent by messing with the structure of how the player is able to causally influence the games’ worlds. But is there a viable alternative to open storytelling? You might be worried that there isn’t: after all, we’ve seen that open storytelling arises almost inevitably from the natural desire to ask “What happened next?”

Thankfully, there is an alternative—and that, as you might expect, is where Dark Souls comes in.

Stoking the Fire: Closed Storytelling and Dark Soul’s Cyclical Act of Creation

The radical alternative to open storytelling is closed storytelling: the creation of a story where no aspect of the plot is left unresolved, and so there is nothing about the story to resolve in a later story. Closed storytelling, unlikely though it may seem, makes it impossible to ask “What happened next?” once the story reaches its conclusion.

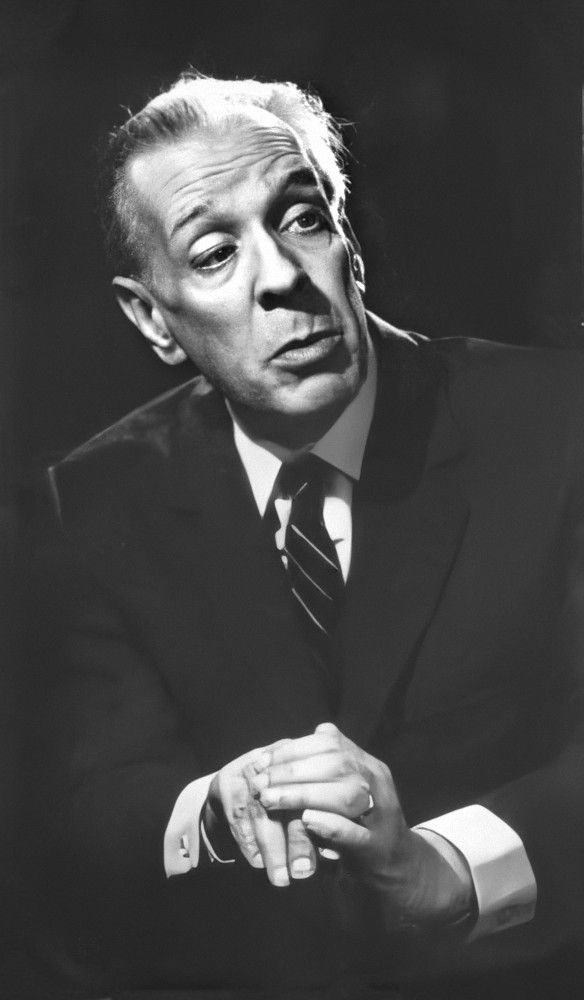

One example from literature—an example strikingly similar to Dark Souls—is Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “The Circular Ruins.” The story is about a man who arrives at ruins with the goal of dreaming a man into existence; he succeeds at this task, only to discover at the end of the story that someone else dreamed him into existence in the exact same way. In this way, the story succinctly describes a cyclical act of creation: one person dreams another into existence, and this continues ad infinitum. That is the total nature of the world that Borges has illustrated for us; it captures both past and future lives, from their inception through their maturity. If someone were to read this story and ask “What happened next?”, you would think that they must be confused—you’d probably assume that they had misunderstood some aspect of the story.

Closed storytelling isn’t something video games invented: Borges is solid proof of that.

Cyclical storytelling is a natural strategy for closed storytelling because it effectively turns time into a loop: in stories like “The Circular Ruins,” the same events unfold over and over again, which means that there’s no mystery prompting us to wonder about what might happen in the future of this world. It so happens that video games are also especially well-suited for cyclical storytelling, and Dark Souls is a master-class example of how this can liberate the medium from the perils of open storytelling.

First, a word of clarification about the aim and scope of my comments about Dark Souls. There are countless websites, wikis, blogs, forums, and subreddits dedicated to mapping out the lore (i.e. the events, world, and history) of Dark Souls’ three full-length games and six story-rich DLCs. I don’t presume to undertake the task of laying out anything like the encyclopedic knowledge that people on these sites have of every Dark-Souls-related tidbit; that kind of lore work has never been the goal of With a Terrible Fate. Instead, I just want to make two observations about how the series executes closed storytelling in an extremely effective way. The first observation is trivial and uncontroversial; the second is a much more controversial theory of my own design that I haven’t seen elsewhere, but that I believe has general explanatory power with regard to the metaphysics of Dark Souls’ world. So far as I can tell, nothing in the Dark Souls mythos outright denies the possibility of the following analysis, so take these as the terms of engagement as we move forward.

To begin with, let’s focus on just the first of the Dark Souls games. The first (and uncontroversial) observation is that, like “The Circular Ruins,” the progression of its world is built around cycles. The world began as a formless expanse ruled by Everlasting Dragons; then, the First Flame and four Lord Souls—the Soul of Death, the Soul of Life, the Soul of Light, and the Dark Soul—came into existence, creating disparity: fundamental contrasts between light and dark, life and death, and so on. From this basic origin story, a cycle of Ages of Fire and Ages of Darkness follows, based on whether the fire of the world fades or is rekindled over time. Gwyn, the original bearer of the Soul of Light, perpetuated the flame and the Age of Fire by kindling the First Flame with his own life. The player’s avatar in the first Dark Souls, the Chosen Undead, appears in Dark Souls’ world at the point when the fire is again fading; ultimately, the player and Chosen Undead must kill Gwyn, who remains bound to the First Flame, at which point they can either sacrifice themselves to rekindle the flame, or else let the flame fade and usher in an Age of Dark.

Gwyn, who was first to rekindle the First Flame, facing the Chosen Undead at the end of the first Dark Souls.

Like “The Circular Ruins,” this setup of Dark Souls’ world and evolution tells us all we need to know about its history, past and future: the world is defined by inevitable oscillations between light and dark, as its fire alternatively rekindles and fades over time. Notice that this doesn’t just render the question of “What comes next” moot: it also makes narrative meaning out of every time that the player decides to replay Dark Souls. At the end of every time through that first game, the player can choose to either rekindle the First Flame or let it fade; after this choice, regardless of which path the player chose, the game restarts, with the player again controlling the Chosen Undead on a path to either rekindle the First Flame or let it fade. This infinite cycle of playthroughs represents the fact that, in Dark Souls’ world, Ages of Fire and Ages of Dark can cycle, one after another, ad infinitum. The player can choose to rekindle the flame once, then decide on her next playthrough to let it fade, ushering in an Age of Dark instead. In this way, Dark Souls succeeds in establishing a world and story grounded in an endless cycle of death and rebirth—not just in the literal gameplay of constantly dying and respawning, but also in the metaphysical sense of the universe progressively oscillating between light and darkness.

When the first Dark Souls established this method of storytelling, it paved the way for sequels that avoided the worst perils of open storytelling. Like the Zelda series, Dark Souls II and Dark Souls III are, at first glance, simple variations on the themes of the first game, set in different eras of the world’s history. The cycle of light and dark continues ceaselessly, and the different games give us different perspectives on that cycle: Dark Souls II gives us the perspective of what it means to be a king in this kind of world, as the player’s avatar (the Bearer of the Curse) first encounters the aged King Vendrick and ultimately faces the choice to ascend the Throne of Want and rule the kingdom of Drangleic or not; Dark Souls III gives us a more cosmic perspective, charging the player with seeking out Lords of Cinder (those who previously rekindled the First Flame, but were too weak to survive the process) in order to use their power to rekindle the dying First Flame—or not, depending on the player’s choice. In this way, Dark Souls as a series is never driven by the question of “what happens next”: the game establishes a world that’s centrally defined by a ceaseless cycle, and then explores various characters who cope with the inevitability of that cycle in different ways.

The Throne of Want, which the player confronts at the end of Dark Souls II.

This cycle of light and dark is absolutely essential to Dark Souls’ world, and the various endings of the three games emphasize that. Aldia—the Scholar of the First Sin and King Vendrick’s older brother in Dark Souls 2—expresses this sentiment directly and succinctly to the player’s avatar: “Young Hollow,” he says, “there are but two paths. Inherit the order of this world, or destroy it.” This is a crucial feature of cyclical, closed storytelling: the world of the story is constructed such that either the world’s cycle will continue endlessly (meaning the audience knows what will happen next, in the grand scheme of things), or the world itself will be destroyed by the avatar, at which point the story will end because the world in which it was grounded has been annihilated.

We’ve already discussed the endless continuation of the cycle, which comes about in the Dark Souls when the player either rekindles the fire, lets the fire fade, or ascends to the throne in Dark Souls II; there are also, however, a few endings that fall into the world-destroying category. In Dark Souls II, the player can reject the Throne of Want, seeking a way to transcend the cycle of light and dark; in Dark Souls III, the player can steal the First Flame for herself, either acting alone or as the new leader of the Sable Church of Londor. In these endings, the player might be curious about what happens next, but whatever happens next couldn’t logically constitute another Dark Souls game: the universe’s light-and-dark cycles are a core, constitutive feature of the Dark Souls stories, permeating everything from the world’s basic structure to the arcs of characters forced to live with the reality of this cycle. One might tell a story about, for example, what happened after the Bearer of the Curse rejected the Throne of Want, but in the absence of Dark Souls’ basic, cyclical metaphysics, the story would be so estranged from the rest of the series that it couldn’t rightly be considered any sort of “sequel”: it would be a new story, complete with a new world.

Leaving the Throne of Want in Dark Souls II means leaving the universe and story of Dark Souls behind.

I think that this is one of the central reasons why Dark Souls is such compelling and satisfying storytelling: the game’s stories never point towards the future, inviting idle speculation about what might happen to the characters down the line. The universe’s basic, cyclical nature decisively settles the matter of what will happen in the future of the world: the fire will wax and wane, just as Undead are cursed to wax and wane through life and death. Characters trapped in this world will find various ways to exist in this cycle, maybe influencing the ebb and flow of light and dark in one way or another; or else, they will find a way to escape the world—at which point, they also escape the story. This is a radical departure from the philosophy of open storytelling: whereas open stories tend to leave people guessing about what might happen after the story’s conclusion, the structure of closed stories keep people laser-focused on the contents of the story itself—that’s because, in closed storytelling, there’s just no way to look beyond the story and its world. Aldia echoes this very sentiment if the player decides to reject the Throne of Want: “There is no path,” he declares. “Beyond the scope of light, beyond the reach of Dark…what could possibly await us?”

Light and dark—lit and unlit bonfires—are an inescapable part of Dark Souls‘ universe.

What I’ve said up until now explains why Dark Souls doesn’t fall prey to the traps of open storytelling, but it doesn’t explain why there could never be a Dark Souls IV. After all, for all I’ve said, Dark Souls could continually add new games that explore different characters at different points in the world’s cycles of light and dark, similar to our discussion of how the Zelda series can tell endless variations of the same story at a variety of points along its timeline.

But I think there really can’t be a Dark Souls IV, and that’s because of the second, much more controversial observation I want to make: I think that the three Dark Souls games and their DLCs constitute a complete and closed system, one that couldn’t be expanded on by another game. To see this, we need to consider the nature of Humanity in the series, and how it dovetails with the act of creating a world.

One of the many wild things about Dark Souls is that the series turns the concept of humanity into both a game mechanic and a meaningful element of its world’s metaphysics. When the four Lord Souls appeared at the start of Dark Souls’ universe, a Furtive Pygmy claimed the Dark Soul—a small, dim soul, seemingly underwhelming when compared to the other three Lord Souls. He used the Dark Soul to create the race of humans, each of whom contains a small fragment of the Dark Soul—a fragment known as their Humanity, their essence that fuels them and links them to the dark. Humanity is what tethers cursed Undead—like the player’s avatars—to their human existence, preventing them from becoming “Hollow,” decrepit and devoid of free will.

The Furtive Pygmy holding the Dark Soul.

The Dark Soul has another functionality, however, as players learn in Ashes of Ariandel, the final DLC in the series: it can be used to create a world. Painters in the Dark Souls universe are able to paint entire worlds, two of which—the Painted World of Ariamis and the Painted World of Ariandel—can be visited by the player and her avatar across the course of the series. In Ashes of Ariandel, the player encounters a new painter who is tasked with painting a new world to replace the rotting Painted World of Ariandel in which she lives. To do this, she needs the Dark Soul itself to use as pigment. Ultimately, the player and her avatar travel to the Ringed City—a place at the ends of the earth where Gwyn sent the pygmies and the first humans—and find Slave Knight Gael, the painter’s uncle, who drank the dried blood of the original pygmy lords in order to absorb the Dark Soul, which mingles with his blood. After they kill Gael, the player and avatar receive his blood, in which the Dark Soul itself manifests. They give it to the painter to use as pigment; she asks for the avatar’s name, because she wants to name the painting after him (or, if the player refuses to provide her avatar’s name, the painter simply names the world “Ash”).

The painter in the Painted World of Ariandel, working on her painting.

I want to convince you that the world of Dark Souls and the Painted World of Ariandel are locked in the act of mutually creating one another—or, put differently, the world that the unnamed painter paints with the Dark Soul is the very world that the player has encountered across the Dark Souls trilogy, from Lordran, to Drangleic, to Lothric. Unintuitive though this may seem, I think that it sheds light on several nagging loose ends in the Dark Souls universe, and it also makes metaphysical meaning out of something that’s obviously important in the series: the players who struggle through these games together.

First, notice that there are two centrally important aspects of the Dark Souls universe that, so far as I can tell, are typically taken to be inexplicable.

- How the universe began in the first place.

- Why the Dark Soul behaves in ways that are fundamentally different from the other three Lord Souls.

Consider first the universe’s origins. The “canonical” understanding of the Age of Everlasting Dragons—the first Age in the universe of Dark Souls—is that, in the beginning, everything was simply formless, ruled by Everlasting Dragons, and then the First Flame inexplicably manifested, leading to conceptual disparity and the four Lord Souls.

This isn’t much of an explanation for how the universe began—it isn’t even as clean as something like the Big Bang. Suppose you understand the Big Bang in the following (extremely reductive) way: at first, there was nothing; then, there was an inexplicable explosion that expanded outwards and became the entire universe. We might still be dissatisfied with the idea that that first explosion was inexplicable, but presumably, any chain of explanation has to bottom out somewhere; so, maybe we could live with the Big Bang being the point at which that happens. But even if we want to compare the appearance of the First Flame to something like the Big Bang, that wouldn’t explain the presence of dragons in an unformed world that didn’t even yet have the basic concepts of light, dark, life, and death. The explanation of Dark Soul‘s creation myth is, in other words, extremely underspecified by the games.

And we can’t throw up our hands and claim that it simply doesn’t matter how the universe’s origins are explained, either, because Dark Souls as a series is extremely invested in explanations of precisely how things came into being. The Painted Worlds are key examples of the game explaining the origins of entire worlds; beyond that, a huge amount of the game’s story is devoted to explaining how its world came to be as it is. To illustrate, here are some selections of the many things whose origins the game explains.

- Demons (born from the Bed of Chaos after the Witch of Izalith tried to duplicate the First Flame using her Lord Soul, the Soul of Life)

- Black Knights (Gwyn’s Silver Knights, who were scorched from fighting with the Demons)

- Sorceries (developed by Seath the Scaleless)

- The Abyss (manifested by Manus, Father of the Abyss, losing control of his Humanity)

- Lords of Cinder (entities who perpetuated the First Flame but were too weak to survive the process)

- Nashandra (a shard of Manus’ shattered soul)

…and so on. So I think it’s fair to say that the origins of Dark Soul’s universe remain unexplained, and that the context of the overall series makes this the kind of thing that warrants explanation.

Now, to the second point, consider the nature of the Dark Soul. Because each of the four Lord Souls embodies a different concept (light, dark, life, and death), it’s to be expected that they each have different properties. But the Dark Soul doesn’t just have different properties from the other souls: it behaves in fundamentally different ways, suggesting that it is essentially different from the other three Lord Souls in some way. Case in point here is the fact that the Dark Soul can be broken into fragments that all retain the powers of the original Dark Soul, meaning that each human, by virtue of containing a fragment of the Dark Soul (their personal Humanity), can grow in power by cultivating their Humanity with emotions and will power. This contrasts sharply with the other Lord Souls, which lose power when split into pieces. Gwyn, for instance, split his Soul of Light into pieces, bestowing them upon Seath the Scaleless and the Four Kings, but neither of these fragments was as powerful as the complete Soul of Light.

If the four Lord Souls really were the same kind of thing, all emerging as four conceptually balanced entities from the First Flame, then we’d expect them all to have the same essence: in other words, they would behave in the same fundamental ways, even though they each have different specific powers (more technically, they should all have the same primary qualities even though they have different secondary qualities). But that isn’t the case: the original Dark Soul can effectively copy itself by fragmenting, something that the other three Lord Souls can’t do. Like the origin of the universe, this demands an explanation, and we don’t yet have one.

My proposed analysis explains both of these two key phenomena. To give this analysis a name, let’s call it mutual-creation theory: the view that the universe of Dark Souls was created by the unnamed painter in the Painted World of Ariandel using the pigment of the Dark Soul, and that the Painted World of Ariandel was created by a painter in the Dark Souls universe. On this view, the Dark Soul isn’t just another of four Lord Souls, each emerging ex nihilo with the First Flame; instead, the Dark Soul is the basic, constitutive element of the entire universe, the literal pigment with which the world of Dark Souls is painted.

Mutual-creation theory explains the origin of the Dark Souls’ universe: the world was initially formless because the painter began the painting without the use of the Dark Soul pigment (we can see at the end of the Ashes of Ariandel DLC, and the early stages of the Ringed City DLC, that she has started the painting despite not yet having the pigment). Because the Dark Soul pigment is what allowed her to give the world form, this pre-pigment version of the painting, populated by things like Everlasting Dragons, was effectively without form. Then, once she was given the Dark Soul pigment, she was able to give the world form, introducing light, dark, life, and death, all using the pigment of the Dark Soul.

The metaphysical primacy of the Dark Soul in mutual-creation theory’s view of the Dark Souls universe explains why the Dark Soul is qualitatively different and stronger the other Lord Souls: every fragment of the Dark Soul contains the power of the original Dark Soul because every fragment taps into the fabric of the universe—the pigment of the painting—whereas the same isn’t true of the Soul of Light, Soul of Death, or Soul of Life. But of course, this explanation invites the following question: why should it be that the fabric of the universe is the Dark Soul, as opposed to any of the other three Lord Souls (or something else entirely)?

I think that the primacy of the Dark Soul in the universe’s metaphysics brings the player of Dark Souls into the story in a way that both renders the overall mutual-creation interpretation of the games coherent and makes the player’s experience with the games distinctly meaningful. As I mentioned above, the Humanity of individuals in Dark Souls is quite literally derived from the Dark Soul: each human’s Humanity is their shard of the Dark Soul. According to mutual-creation theory, Humanity derives from the Dark Soul because the Dark Soul and its fragments are conduits for the player’s real humanity.

Why is this so? Well, what we have in Dark Souls, according to mutual-creation theory, is something like a perpetual-motion machine: the painter is creating the universe of Dark Souls even though the very painting in which she exists was created by someone in that universe. Presumably, you need some kind of external force to catalyze this kind of perpetual cycle of creation between the Painted World and Dark Souls’ universe. This external force, I think, is the player actually playing the games.

That might seem like a trite point, but I think it’s actually to the immense credit of Dark Souls that it takes something potentially trite and instead makes it robustly, metaphysically meaningful within the fiction of the game. The game has a metaphysically foundational mechanism for introducing Humanity itself into the world: the Dark Soul. And Humanity, within the universe of the game, is explicitly manipulable by the exact forces you’d expect to impact one’s humanity in the real world: emotions and will power. So I think that this analysis of the series marries its video-game form with its story’s content in a new and illuminating way: the player isn’t just moving the story forward by playing the game, as is the case in any video game—they are also thereby, within the game’s fiction, creating the world of the game, by using their humanity to catalyze the reaction of the Dark Souls universe and Painted World of Ariandel creating one another, through the mediating force of the Dark Soul. The entire universe of Dark Souls, then, is inert until the player engages with the game, and it is the player’s struggle with the game—their emotions and will power as they struggle through the game—that fuels the Dark Soul, perpetuating the mutual-creation reaction.

The two words that best represent the “struggle” I’m taking about.

Before I continue, let me make three comments above the general plausibility of mutual-creation theory.

- Should it count against the theory that the notion of one world creating the very same world that creating it is incoherent? Yes, but that consideration shouldn’t be treated as a decisive consideration that defeats the theory. Plenty of what we see in works of fiction is incoherent, while still making for a compelling story. Most—if not all—time travel stories are incoherent, because you can’t make sense of causal histories in a coherent way when time travel is involved. And on that note, it’s worth keeping in mind that Dark Souls already involves time travel: the Chosen Undead travels back in time to the kingdom of Oolacile in the DLC of the original Dark Souls. So while it should definitely count against the theory that it introduces more incoherency into our understanding of Dark Souls, it’s not as if the story was perfectly coherent in the first place. Moreover, the charge of incoherency against mutual-creation theory isn’t as severe as it would be if the theory claimed that two worlds created each other ex nihilo: the entire creation process is catalyzed by the player, an agent who exists independently of the reaction, which at least gives us some kind of independent grip on what caused these two worlds to come into being (even though, technically, what we have is an explanation of what caused the worlds to create each other—which is why we haven’t altogether explained away the charge of incoherency).

- Should we worry about the idea that someone who exists within a painted world—i.e. the painter—is able to create the “real” world that exists outside of that painting? I don’t think so; according to mutual-creation theory, the Dark Souls universe and the Painted World of Ariandel are both painted worlds, painted from the pigment of the Dark Soul. This means they’re ontologically on a par, and so this potential worry is no real worry at all. And even though we initially assume the Dark Souls universe isn’t painted, that’s not a consideration that should count against the theory: there’s nothing especially “painting-like” that distinguishes the visual features of the Painted World of Ariandel from the Dark Souls universe at large, and so it seems at least possible that both of them could be painted worlds.

- Should we dismiss this theory because it isn’t explicitly confirmed by in-game content or Dark Souls creator Hidetaka Miyazaki? No. As I said above, my project here is not to catalogue and adjudicate the explicit, “canonical” events of the Dark Souls series. What I’m doing—as I always do in my work on With a Terrible Fate—is to put the entirety of a game’s story and world in view, and develop an analysis that allows us to understand the entire ecosystem of that fiction in the most illuminating way possible. Such a view had better cohere with the game’s content, but it’s under no obligation to be explicitly confirmed by the game or its creator. But what I’m doing also isn’t simply idle “speculation”: mutual-creation theory is an example of a systematic, analytically rigorous approach to what every gamer does all the time, whether they want to or not: gathering all of a game’s content in their mind and developing a view that allows them to make as much sense out of that game as possible.

So I think that, ultimately, mutual-creation theory is much more plausible than it may initially seem. It also makes precise one of the most mesmerizing features of the Dark Souls franchise: the fact that players’ experience in playing Dark Souls tightly mirrors their avatars’ experience. Both player and avatar are fated to fail again and again while struggling through Dark Souls, and it is only through will power and dominion over their emotions that they can eventually prevail; mutual-creation theory takes this observation to the metaphysical level by claiming that the player’s will power and emotions are actually what create and perpetuate the universes of Dark Souls and the Painted World of Ariandel. This is made even more poignant by the painter deciding to name the universe of Dark Souls after the avatar, whom the player named: in so doing, she is effectively acknowledging the responsibility of the player for the creation of that universe.

Mutual-creation theory should also make clear why there couldn’t be a compelling Dark Souls IV: Dark Souls III—specifically, its final DLC, in which the painter paints the universe of Dark Souls—is a perfect metaphysical bookend to the series. The story concludes with the creation of the very universe that the player first encountered in the original Dark Souls. To try to move beyond that—to ask “what comes next?” when you’ve just been shown the completion of the creation cycle at the heart of Dark Souls—is to ignore the most foundational structure of the game’s world. The trilogy and its DLC represent an effective closed circuit of a world creating the world that created it, which is the most absolute denial of open storytelling that I can imagine. That’s why Dark Souls never would have been able to continue in a compelling way even if Miyazaki had wanted it to continue; and the deep sense of completeness that comes from the series describing a totally cyclical universe is why it’s a good thing that it can never continue.

Final Notes

It’s worth noting that Dark Souls isn’t the only game that exploits closed storytelling to great effect. Briefly, here are four other central cases.

- Majora’s Mask drops Link into Termina, a world that cycles through countless loops of the three days leading up to its apocalypse, much like the movie Groundhog Day. I’ve argued before that Link can never really escape this time loop: Termina is just an infinite chain of three-day timelines leading up to the apocalypse, a paragon of closed storytelling.

- Xenoblade Chronicles ends with the literal destruction of the game’s universe and the creation of a new one, thereby ensuring that any further story (including its upcoming sequel) will not be a direct extension of its own story. This world-ending conclusion is a classic way to execute closed storytelling, especially in JRPGs.

- BioShock Infinite describes the quantum collapse of an entire universe, using physics to explicitly reinforce that whatever “happens next” in the story is entirely random. That’s yet a third way of executing closed storytelling: making the future irrelevant by making it random, virtually the opposite of making the future perfectly predictable like Dark Souls‘ cyclical universe does.

- Bloodborne uses the same cyclical structure as Dark Souls’ universe, except it traps the player within a cyclical, endless dream, rather than in an endless progression from dark to light and back again.

I could go on, but the point here is that many of the video games I analyze on With a Terrible Fate are examples of closed storytelling. I don’t think this is mere coincidence: I’ve always seen the metaphysics of game worlds as central to understanding games’ stories, and games that specify their worlds’ metaphysics tend to tell a story about that entire world. That’s exactly the kind of story that’s a prime candidate for closed storytelling, and I think it’s also some of the most interesting kind of video-game storytelling because games whose worlds have a clearly defined metaphysical structure tend to thereby also specify particular relationships between their player, their avatar, and their world. As I’ve emphasized many times before, these relationships are where all the action happens in the special storytelling of video games.

And lastly: should we not approach closed storytelling like Dark Souls’ with at least a touch of melancholy, knowing that such great stories cannot continue indefinitely? I don’t think there’s any need for melancholy, because even though Dark Souls won’t ever have another sequel, it has “sequels” of another sort. Closed-storytelling games like Dark Souls can live on by inspiring the structure of other games with different stories. Dark Souls is a great example of this because it spawned Bloodborne, a game that uses the same closed storytelling with a cyclical world, but does so while telling a totally different story, invoking different themes, and linking the player to that world in a radically different way. More recently, Nioh has picked up the torch to tackle that same kind of Dark-Souls-esque storytelling in feudal, magical-realist Japan. This kind of structural inspiration can give us the best of both worlds: games get all the benefits of closed storytelling, while still being perpetuated over time through new stories that invoke the same specific kind of closed storytelling.

Bloodborne, one of the many heirs to the Dark Souls storytelling mantle.

So I do miss Dark Souls, and I’m sure I always will. But it’s finished, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.