LAN Party (Let’s-Analyze-Now Party) is a monthly feature where we ask With a Terrible Fate’s analysts to answer a prompt about their personal experiences with gaming. Answer the prompt for yourself, and join the discussion!

Welcome to the inaugural issue of LAN Party, a new series designed to get With a Terrible Fate’s video game analysts sharing some of their formative gaming experiences that shaped their perspective on the storytelling medium. Each month, we prompt the analysts with a different, gaming-related question. Check out their answers, share your own answer with us, and let’s start some new conversations about our most memorable moments with video games.

This first prompt got analysts talking about the games and moments that led them to become video game analysts. The prompt was:

What was the first game that inspired you to think seriously about analyzing video-game storytelling? What was it about the game that so inspired you? Have you gone back and replayed it in the time since that initial epiphany? If so, what was that experience like?

Jaron R. M. Johnson (Video Game Analyst)

For me, as I imagine it is for many people, the first game that started the analytical wheelhouse on video games within my brain was The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. It was the first game that gave me a true sense of immersion, where I felt connected to the character I was controlling. I’ve always felt like an oddball, like I was somehow out of place, even among people to whom I’ve been connected my entire life. Putting myself in Link’s shoes couldn’t have been easier: a young, left-handed boy, who had a knack for adventure and an affinity for the color green? A child who discovered that the nature of his differences (for Link, the lack of a fairy) was actually the first step in finding his destiny? What more could I have ever wanted out of a video-game story?

I got lost in the worlds I was wandering through, and it felt exactly like that: like I was wandering through them. Not just that I was seeing them on the screen and making my character roll around them endlessly, but that somehow I was right there, in Hyrule Field, or The Temple of Time, or Jabu-Jabu’s Belly. That immersion was key in the way I allowed myself to get lost in the journey of Link. It should be of no surprise that this sparked my interest in storytelling, which is nothing short of analogous to me finding my own fairy.

I’ve gone back to play Ocarina countless times, and each subsequent time finds me feeling like I’m returning to a home. Familiar places I’ve traveled to. Familiar characters that recognize me, that boy in the green clothes. It is this sensation, in part, that led my brother and I to start examining this particular iteration of Link and his implied personal journey through life. You can read more about how we envision that in our Hero of Time Project.

Nathan Randall (Video Game Analyst)

I’d like to get even more specific than just which game first inspired me to think seriously about analyzing video-game storytelling, and talk about one particular moment that did it for me. Xenoblade Chronicles has a character death very early in its story—about six or seven hours, at most, into an eighty-hour game. The death of this character serves as the call-to-action for the protagonist of the game, as well as two of his comrades. The scene where the deliberation is made is a heartbreaker: the two best friends of the girl who died stand on her favorite hill and look out at a sunset over their very small city, blaming robots called Mechon for her death, and swearing to kill them all in response.

At the time, the protagonist’s goal seems fairly reasonable, and most players probably buy right into it and also desire to bring about the demise of the Mechon. But that feeling ends up being misguided, once the player learns about what the Mechon are and why they were created. In this way, large swaths of the game end up being about the gradual unraveling of naïveté, and seeing what the characters in the game consider to be pillars of the universe collapse. It’s a beautiful story, one that we here at With a Terrible Fate have written about on several occasions.

What amazes me about this game is how its construction fools not only the characters in the game, but likely also the player herself into believing that the world of the game works in a particular way. Even though the protagonist’s initial decision to kill all the Mechon is a naive, destructive, and unfortunate one, the player goes right along with him. The scene in which he makes the decision looks beautiful and meaningful, with a beautiful sunset and background string music. What the player misses, which becomes painfully obvious on a second playthrough, is that the sunset is equal parts beautiful and foreboding because the characters are about to be plunged into the dark of night. And the music is not just beautiful: it’s also tragic. It tells of a future full of pain. The scene is set up to trick the player into siding the with protagonist, even while warning the player that the protagonist’s decision is misguided.

The moment hit me in a big way in my senior year of high school, back when I was playing a lot of instruments and thinking really hard about the potential emotive power of music. To see a game use its music so potently as a storytelling mechanism astounded and inspired me. It clued me into the special potential video games have to tell stories that avail themselves of the unique features of many media—from music, to film, to choose-your-own adventure novels. If you’d like to explore the music of Xenoblade in more depth, you can check out my work on it here.

Peter Finn (Video Game Analyst)

I think the first game I played that encouraged me to think about video game storytelling more analytically was Enslaved: Odyssey to the West. I respected its realistic dialogue, its focus on telling a classic tale, and the fact that the game took time to develop its characters in quieter moments. However, I couldn’t escape the nagging feeling that I wasn’t really invested in the events on the screen, and I wondered why I felt this way in spite of all the things the game did so well. Addressing this thought was the basis for my first personal blog post in years, and from this, I got into the habit of reviewing every new video game I played—something I did for months, until I joined With a Terrible Fate.

I haven’t gone back and replayed it yet, but I absolutely plan to someday. It’s got too many interesting qualities to ignore. Furthermore, I’ve toyed with the idea of doing a retrospective on the stories told by the developer Ninja Theory, and this would mean revisiting Enslaved: Odyssey to the West.

Aaron Suduiko (Founder, Chief Video Game Analyst)

While the first work I published on With a Terrible Fate focused on Majora’s Mask, my first inspiration to analyze video games came two years earlier in my senior year of high school. On a visit to GameStop, I stumbled upon a copy of the game Nier—a game where (as the back of its case promised) “Nothing is as it seems.” At the time, I was heavily involved in the study of both theater (playwriting, directing, and acting) and Buddhism, and so questions of identity (“What constitutes a self?” “What does it mean to play a role?”) were constantly on my mind. Once I picked up Nier and discovered that its entire plot revolved around questions of identity, I began to wonder what light video games could shed on this topic that had been dogging me. What did it mean for a player to “inhabit the role” of an avatar? How was that similar and dissimilar to an actor inhabiting the role of a character in a play?

Nier inspired me to spend my final semester of high school comparing the role-playing dynamics of video games with comparable dynamics in plays. I compared:

- Majora’s Mask and Six Characters in Search of an Author

- Dishonored and Macbeth

- Nier and The Man in the Iron Mask

- Deus Ex: Human Revolution and Flowers for Algernon

The more time I spent studying how video games created stories, the more strongly convinced I became that they had something unique to offer the art of storytelling—something we haven’t seen before, and that we still have yet to see elsewhere. And it’s no coincidence, I think, that this first work I did also involved Majora’s Mask—the identity-obsessed game that became the cornerstone upon which With a Terrible Fate was built.

CJ Thomas (Video Game Analyst)

While I’ve always had some fairly intense thoughts on video games in general, I think the game that really pushed the limits of my thinking was probably Mass Effect 3. Mass Effect, in my mind, had already been knee-deep in this incredible revival of the spirit of Star Trek with its well thought-out lore and its logically presented themes and decision-making; but the ending to Mass Effect 3 was so bad I found myself going out to find out why it was bad.

I found the typical responses—it needed more light shed on the events after; it needed the situation to be fleshed out—but none of those answers really satisfied me. Eventually I did find an amateur journalist who took the whole ending in a completely different light: he brought up H.P. Lovecraft, Star Trek, and tons of other things I just had no idea could have applied so heavily to the plot of Mass Effect. It was enough to change not just the way I think about the games I play, but also the way I play them to begin with.

Lately my big thought has been about stretching the limits of the relationship between you, the player, and the game. Hopefully, in my writing, I can flesh out what that stretch should look like, and maybe some day I’ll open someone else’s eyes to this thought, too.

Richard Nguyen (Video Game Analyst)

I did not come to appreciate the storytelling power of video games until much later in my life, even though I’ve been intimately engaged with the medium across a wide range genres and platforms since I was 4 years old. To me, the games I played and stories I experienced from them were always secondary in capability and depth to film, my other favorite art form.

That is, until I played Journey in my junior year of high school, which impacted me so deeply that it forced me to reassess my perspective on video-game storytelling. Here was a game that was so different from anything I had played before, but that was still so undeniably interactive and engaging. You toil and toil, platforming and traversing through a barren desert with the help of an anonymous player, until you reach the mountaintop that was nothing but a speck at the very beginning of the game. Its ending reveals a larger metaphor of the journey humans embark on—not only in the process of a video game, but also in life itself. Its depiction of only nearing the very end, but never quite reaching it, as my character and my friend’s froze to death, left a momentary feeling of emptiness and disappointment in me. Were my efforts futile?! Could I have somehow played the game better? What was even the point of it all? And then it struck me. The meaning was contained in the title itself. My real enjoyment of the game came not from reaching the destination, but rather from the journey itself. Here I was, so driven by reaching this presumed goal that I did not realize that the reward was in the beautiful sights and human moments I encountered along the way. The epilogue’s portrayal of a beautiful afterlife in the clouds was a nice touch, but felt more like an obligatory means to appease players who may have needed more closure. The game ends only to begin again, from the very beginning. The game gives the player no trophies, gold medals, or other substantial recognition of completion. It merely starts again from square one. And yet, knowing that there was no real happy ending to this story, I began my second playthrough immediately, excited to see once again the beautiful moments I encountered before my inevitable death.

From that point on, I more closely examined the player-avatar relationship in the games I played, and found that there can be substantial meaning imbued in the choices a player makes and how that affects the not only the video game’s story, but also the player themselves. That fundamental feature of video games—the continual demand on the player continually make decisions—is something that I realized no other medium can achieve. In Journey’s case, it was my decision to continue to play this abstraction of life, even though I knew it would only lead to death, that made me realize that it is the journey, not the destination, that truly matters.

Chris Anhorn (Video Game Analyst)

For me, the first time I really started engaging with video games on a more intellectual, analytical level, rather than seeing them just as a fun and engaging way to pass the time, was probably with Knights of the Old Republic II. I’m not sure why I started playing that one before the original—honestly, I don’t think I was even aware that the first one existed, beyond the fact that this one was explicitly titled as a sequel. Ostensibly I was interested in the game because it was Star Wars, and at that point (I was eleven or twelve), anything Star Wars was good to me. But the nature of that game, unfinished and buggy as it was, was incredibly poignant and fascinating to me. Its philosophical explorations of morality, war, apathy, and nihilism (among other things) really hooked me in a way that I did not experience from other forms of media I was consuming that featured similar themes (bear in mind that this was right smack-dab in the middle of my Vonnegut years). In that way, I think that it was my first experience with video games where I understood the storytelling possibilities distinct to the medium: I spent so much time wandering through the Ebon Hawk and listening to Kreia’s (superbly voice-acted) diatribes that the background music is imbedded in my brain.

Although I started countless playthroughs of differing moral alignments, invariably I always came back to an evil one. There was something about the atmosphere, tone, and aesthetic of this game that always drove me to malice, misanthropy, and isolation. I always left it feeling a little sad.

I did unearth my ancient, embattled, old Xbox a couple years back to give this one another playthrough, and it certainly holds up. If only we got a proper sequel…

Dan Hughes (Video Game Analyst)

There were a lot of moments playing games as a kid when I knew that what I was experiencing was amazing; these moments definitely had an impact on me, but I was only able to really verbalize it later in high school. The class I designed in high school took those games I had played as a kid and put them in an analytical light, with one of my goals being understanding those childlike moments of wonder and explaining why they had that effect on me. I dove into what it meant to be heroic in Ocarina of Time, why the schmaltz of friendship in Kingdom Hearts is a brilliant example of theming, and the undeniably tragic look at depression, loneliness, and mental anguish explored in Silent Hill 2. And while I could, have, and will, wax philosophic about those games, there was really only one game from my childhood that presented me with a profound lesson whose meaning and profundity I was able to grasp as an eight-year-old: Pokémon Silver Version.

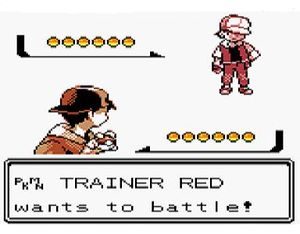

I was a huge fan of Pokémon, just like the rest of the planet, and when Silver Version was released, I played it until I literally wore the battery of the cartridge out and had to buy a new one. I plan on going into greater depth with the Pokémon series in my Now Loading series (see, for example, my article on Pokémon Red Version), but I’ll just say that, even as a wee bab, once I’d beaten the Elite Four and was able to travel back to the Kanto region, my mind was blown to discover that things had actually changed, and that it seemed like my actions from the first game had really affected the wonderful world of Pokémon. Now of course, it wasn’t my actions specifically that had affected the world, but the implication that the previous game and your had existed in this world blew my tiny socks off. Imagine my surprise, then, when I discovered the true final boss of the game—the biggest, baddest, and strongest trainer—is actually Red: your avatar from the previous game, Pokémon Red Version.

I remember immediately thinking how this character was amazing for having beaten all the odds and continued forward until there were no other challengers before him—with training, I thought, I might become the strongest, too. After all, I thought, if my avatar from the last game came this far, surely I can go even further. Beating Red in Pokémon Silver Version was the first time I can remember a game presenting me with a theme, challenging my understanding of said theme, and then reinforcing the central message of the series through my own actions. You can always keep moving forward and getting stronger, even when you think you’ve reached your ultimate limit.

Pretty cool stuff, Pokémon.

Laila Carter (Video Game Analyst)

For me, it was Darksiders II. Most of the games I had played before that were all on Nintendo consoles, and Darksiders II was my first game on Xbox 360. I got it initially because you play as the incarnation of Death, which is pretty sick, but now I play it over and over again because of its world-building, story branches, and gameplay. The gameplay is fluid and smooth, the story takes you to several fabulously constructed worlds and landscapes, and the puzzle-solving exercises my brain (I make it a point to forget how I beat games so that I can play them again).

What made me really think about storytelling, however, was that Darksiders II reminded me of The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess. TP was the first game I ever fell in love with, replaying it a thousand times and never getting bored. However, I never really thought about analyzing the story at the time. Then, after playing Darksiders II, I could not stop comparing the two and seeing how one handles story differently than the other, as well as character development, interactions, gameplay, dungeons, world-building, and suspense. Though the structure of each game is fairly similar to the other (large world divided into dungeons with story progression), the games are vastly different. And yet I love them both equally, because they both give me the feeling of true exploration of a world I’ve never seen, and wanting to become a better hero/fighter than I initially was.

Kent Vainio (Video Game Analyst)

For me it was definitely Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc, a visual-novel game produced by Spike Chunsoft. The game revolves around a group of high-schoolers who are trapped inside their school, with the only way to escape being to kill another member of the group and then be acquitted in a class trial afterwards. You play as Makoto Naegi, the Ultimate Lucky Student, and help him to solve the murders that occur in each chapter of the story. Danganronpa employs a mixture of highly complex themes in its story, questioning both the morality of the main protagonist and the game’s titular antagonist, the black and white bear Monokuma, as well as the moral rectitude of acting unlawfully in a situation of survival. Throughout the game’s 20-hour story, the player is confronted with many difficult situations in which there is no clear moral high ground, and is thus forced to reconsider how they view humanity in various different contexts.

The game also creates a very strong feeling of being trapped within its world. And by this I mean that the players feels psychologically and empathically involved in the game world to such an extent that, after playing, one finds oneself still ruminating over what happened in previous playthroughs and worrying about events to come, such as which characters will die next. Although the game takes the form of a visual novel, which means that player interactivity is limited to certain sections of the plot, it still manages to create this sense of immersion through the parts of the game that the player can influence. Investigating murders with one’s fellow classmates and then gathering up all the evidence to successfully prosecute the culprit during a trial is immensely engaging and really makes the player feel involved in a living, breathing game world. The game’s bold, comic-book-like art style and almost childish music also contribute to the highly unsettling atmosphere of the visual novel: by casting the morally ambiguous events of the story in a highly simplistic light, they both make the player feel constantly mocked and also further reinforce the terrifying, murderous intent of Monokuma, who views the entire killing game as a form of fun entertainment, rather than as a harrowing fight for survival against all odds.

It is in this light that Danganronpa made me think more seriously about analyzing video-game storytelling. It taught me how effectively video games can immerse their players in their stories and make them question their values and presumptions about the world, something that I decided was highly exciting and worth sharing with others on a site like this one! I have not yet replayed Trigger Happy Havoc; however, I have played Danganronpa: Goodbye Despair, the second game in the series, and am currently playing the third one, Danganronpa V3: Killing Harmony, which was just recently released. Both the second and the third game continue where the first one left off, not only in terms of their engaging stories but also in regard to the highly thought-provoking moral questions that they raise. Danganronpa is a truly fascinating series, one that I highly recommend to any video-game fans out there!

What stories first led you to recognize the storytelling potential of video games? Let us know in the comments!

And tune in on October 31st for a LAN Party Halloween special: our analysts’ scariest moments in gaming.