Does every video game tell a story? More precisely, how does one determine whether or not a game is telling a story? At heart, video games are games, but with many venturing into the world of literature, it has become more difficult to separate the games from the stories.

Minimalism, the artistic technique of sparingly providing information, has only exacerbated this difficulty. A popular design philosophy, minimalism sees video games avoid explicitly presenting information, relying instead on the subtle exhibition of detail. The Witness is one such game, but its use of minimalism stands out from the rest due to how thoroughly the game applies the philosophy. The Witness employs minimalism in all aspects of its design from its gameplay to its story, and this design philosophy creates a major problem: the player cannot determine whether the game is telling a story.

We’ll begin by establishing how The Witness tells its story in a minimalist manner. From there, we’ll explore how this minimalism hinders the player’s ability to access the game’s story. Finally, we’ll investigate how other games succeed where The Witness fails in an attempt to propose a possible solution to the game’s storytelling flaws. By examining the faults in how The Witness implements minimalism, we can use the game as a case study to demonstrate how minimalism, when taken to an unreasonable degree, prevents a player from recognizing that a game is telling a story.

The Subtle Storytelling

Before we delve into the flaws in the storytelling of The Witness, we must first establish the story of the game and how the game presents it in minimalist ways. In The Witness, your player character is a playtester for a game currently in development. You find yourself on an island devoid of people to interact with. All non-player characters remain frozen in stone. As the playtester, you possess only one job: solve puzzles to ensure the game functions properly. Puzzles appear as panels with screens, and to solve them, you must follow a line from its start to its end.

This information serves as the set-up for the story of The Witness; however, said story deviates from what one typically defines as a “story.” As generally defined, a story sees a character or group of characters following a sequence of events that involves them facing a conflict of some sort, eventually leading to the communication of one or more themes. In contrast, the story of The Witness doesn’t involve your character facing any sort of “conflict” as typically conceived. Instead, the story of The Witness is about you, the player, interpreting the unknown world around you. The game creates opportunities for the player to develop their own interpretations of the information presented to them from within the game, be it through the puzzles, world, or hidden items. Through these opportunities, The Witness encourages the player to develop their own interpretations, their own worldview; this development serves as the story in The Witness. From the player’s perspective, though, this information isn’t apparent—the game doesn’t establish the development of interpretations as its story.

However, one could argue that the player’s journey as a playtester functions as the game’s story. The most significant piece of evidence in support of this interpretation is The Witness’s secret ending, where a video plays in which a man, presumably a developer, wakes up and walks around the development office. Representing the player character, the man seemingly is the playtester of the game. One might be tempted to use this ending to justify the argument that the playtester journey is the game’s story, but it makes little sense to base that argument on an optional, endgame secret. Secret endings in games can provide further information about the game’s story, but constructing a story around optional, endgame content is inappropriate. While this ending provides key information on the role of the player character, basing the entire story on this hidden ending seems illogical.

The room pictured above exists in the mountain, and it displays concept art for various areas around the island.

To reach this ending, the player must solve a puzzle using an electrified gate in the game’s starting area. However, if the player doesn’t find this secret, which they most likely won’t if they are a first-time player, they can only unlock it at the end of the game. In the game’s secret area—the caves, which are available only at the end—the player finds a drawing of the puzzle that deactivates the electrified gate, but the drawing shows a specific solution to the puzzle. If the player returns to the gate and enters the solution, then the gate reactivates, and they can complete the puzzle, leading them to the secret ending.

For a first-time player, finding this secret alone proves to be near impossible. First, they don’t know about the secret solution to the puzzle, so they won’t find it initially. Second, they need to complete the cave area, which contains some of the game’s more difficult puzzles, to find the proper puzzle solution. Third, the player needs to remember that the puzzle was in the game’s starting area, which they have had no reason to return to until now. Fourth and finally, they need to solve the puzzle to unlock the secret ending.

All of these actions ask far too much of a first-time player. They would most likely need to consult the internet to find this secret, more so to determine that it even exists. While the video in the game’s secret ending supports the interpretation of the playtester journey, the ending itself serves only as an extra secret to elaborate on the story of the game, so an argument that uses this secret ending to conclude that the playtester journey is The Witness’s story is not compelling.

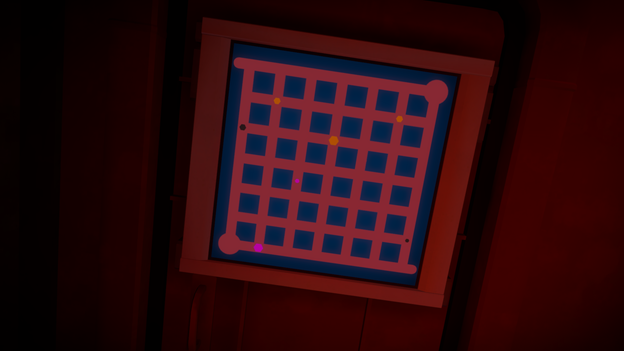

Since we’ve established the story of the game, let’s now examine the gameplay. As previously stated, puzzles in The Witness consist of drawing a line from one end of a panel to another. While that may sound simple, the game expands upon this concept by employing different rules that the player must satisfy in following the line—these rules range from separating black and white squares to outlining different shapes to pairing specific icons. The island that the player explores throughout the game contains eleven primary areas alongside a few optional areas, each manipulating the puzzle rules to produce unique gameplay experiences.

The above screenshot depicts the opening hallway of the game with the first panel puzzle.

Through both the story and gameplay information outlined above, The Witness introduces its players to the minimalism that pervades its every aspect, for the game never explicitly states any of the aforementioned details. Recognizing that you are playing the role of a playtester requires you to find secret details in the game: the secret ending, concept art of the game’s regions, miniature wooden models of the game’s buildings, and cassette tapes that replay conversations from the perspective of the fictional developers. Learning the puzzle rules demands that you, the player, infer them from a collection of simple examples designed to demonstrate the nuances of said rules. There is no text; there are no explanations; The Witness simply leaves the player to interpret the rules themself.

Here is one of the first sets of puzzles designed to teach the player the rules. In this case, the rule requires them to have all white tiles and all black tiles on opposite sides of the line.

This minimalism plays an integral role in the game’s story. The Witness is a game about ideas—ways of interpreting reality—and it emphasizes this definition of “ideas” in two primary forms: (1) by creating opportunities for interpretation via the puzzles and world and (2) by conveying various interpretations of reality from historical thinkers. In both instances, minimalism remains the method of presentation to allow for as much interpretation as possible. The ultimate goal of The Witness is to invite the player to generate their own interpretations of the real world—their own ideas—and to do so while providing as little outside influence as possible.

Ideas Through Gameplay

To further examine how the game uses minimalism to present these ideas, this section explains how The Witness minimalistically conveys ideas through its gameplay. Creator of The Witness, Jonathan Blow, described the panel puzzles as such in a Time interview:

But there’s also a layer at which the puzzles are at least metaphorical and about understanding the world that we’re in…. They’re not just a thing you solve. There’s an idea behind each one, whether you consciously realize it or not.

In this quote, Blow reveals that he intends for each panel puzzle to reflect a way of understanding reality, defining said way of understanding as “an idea.” Evidenced by this information, every panel puzzle expresses an idea, an interpretation of reality.

Featured above is a statue of a man reaching for a goblet. His shadow makes it appear that he is holding some object.

Aspiring to this goal, Blow implements minimalism in an attempt to convey these ideas without any biased commentary. Later in the interview, he states, “That’s part of what makes the puzzles compelling, that the idea goes into your head a little bit.” Vaguely hinting at the larger goal of the panel puzzles, Blow explains that he aims to have the player think about these ideas. At no point does the game even allude to the panel puzzles as representative of interpretations of reality, and through this minimalism, The Witness asks the player to interpret each panel puzzle as they see fit.

Blow designed the panel puzzles with the goal of presenting an idea and having the player rationalize that idea. For example, the rule of separating black and white tiles may serve as an allegory for the segregation of society by race, or perhaps it may argue that two sides exist in every situation—one black and another white. By sparingly providing information through the panel puzzles, The Witness stimulates the player’s individual interpretation as a means of filling in the blanks, be it with the race allegory or something else. In this case, the game uses minimalism in an attempt to cause the player to develop their own interpretations of reality.

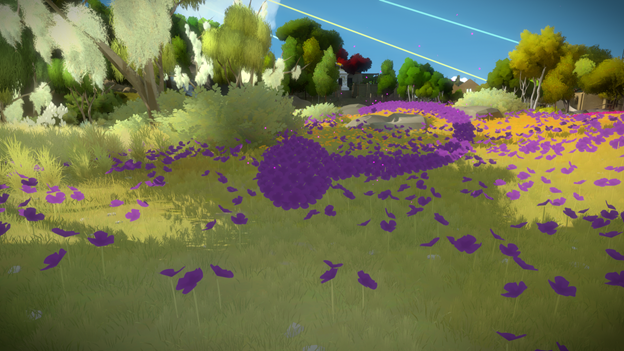

Alongside the panel puzzles, a second type of puzzle exists in The Witness: environmental puzzles. Like with the panel puzzles, the player must follow a line from start to end, but that line exists in the game’s world. The environmental puzzles remain completely hidden to the player, and to discover these puzzles, they must view the game’s world from a unique perspective, usually requiring proper orientation or noticing trends in colorization. Refraining from notifying the player of this unique game mechanic, The Witness instead goes radio silent.

Withholding this information from the player plays an important role, for the lack of knowledge about these puzzles results in the player having to discover them organically. Through this gameplay dynamic, The Witness once again employs minimalist storytelling. Since the puzzles hide within the environment, the player must closely analyze it, looking at the world from multiple perspectives until they uncover the proper one that reveals the environmental puzzle. Through the minimalist presentation of the environmental puzzles, The Witness subtly presents the idea of looking at reality from numerous perspectives.

This screenshot displays an environmental puzzle on the peak of the mountain. The river reflects the shape of the panel puzzle above it, and the player can solve it by clicking on the large circle.

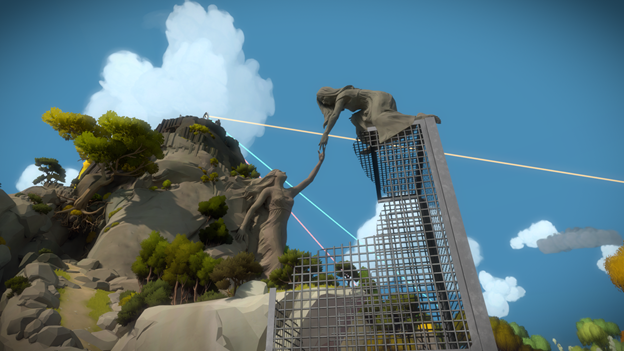

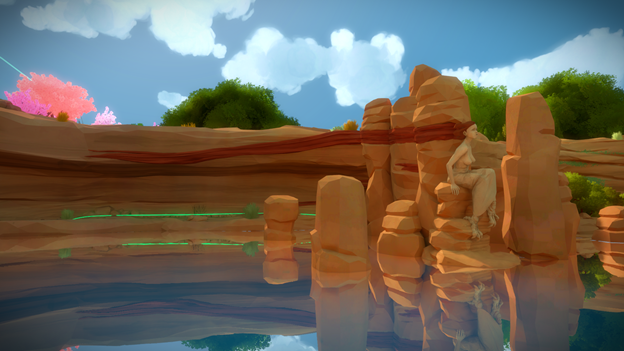

Beyond the environmental puzzles, numerous hidden images exist within the game’s world: a woman with incredibly long hair sitting on rocks, flowers in the glare on a piece of wood, the shadow of a woman hiding on a rock face, two women reaching for each other (this is the most famous example), and so many more. Like the environmental puzzles, The Witness never explicitly acknowledges that these images exist; instead, it asks the player to discover them of their own accord. To find them, the player must once again search the environment for the proper perspective that reveals the image. This instance of minimalist storytelling parallels that of the environmental puzzles as it enforces the idea of looking at the world in different ways.

Here is the hidden image of two women reaching for each other. One of the women is in the mountainside, and the other is in the swamp below the mountain. Proper positioning reveals this spectacle.

Ideas Through Tapes

Another instance of the minimalist presentation of ideas can be found in items hidden around the game’s world. Across the island of The Witness, the player may find cassette tapes strewn about. Each tape quotes a profound historical thinker, ranging from theoretical physicist Albert Einstein to theologian Nicholas of Cusa, and presents a way said thinker interpreted/interprets the world—one of their ideas. Not only do these tapes remain important to The Witness’s story: they also demonstrate one of the key ways it utilizes minimalism to tell that story.

As with the common trend, the game doesn’t tell the player that such tapes exist. It falls on the player to uncover these tapes and the ideas they hold. But when a tape plays, it provides only a vocal reading of the quote signed with the author’s name. The Witness does not comment on these quotes in any way; rather, it simply presents the quote and leaves the thinking to the player.

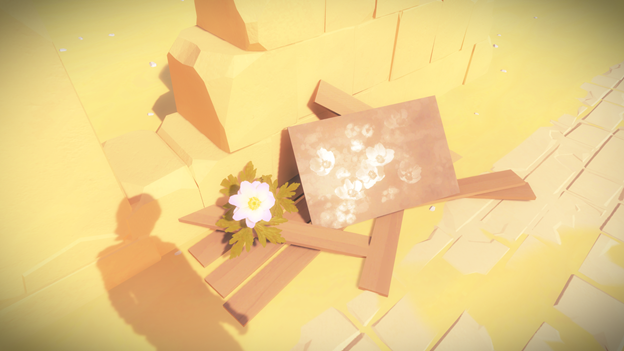

Tapes like the one featured above lie hidden across the island and contain quotes from profound features.

This case demonstrates minimalism to the extreme, for the game presents no information as to why each quote and the ideas it holds matter to the larger picture of the game’s story. Thus, The Witness shifts the responsibility of determining the significance of each quote onto the player. By placing this burden on the player, the game intends for them to evaluate the importance of each quote and its ideas as they see fit. Capitalizing on minimalist storytelling, this technique encourages the player to think for themself by providing as little information as possible to leave as much room for interpretation as possible.

Ideas Through Videos

Beyond the tapes, six secret videos exist in the game’s world, and they exercise minimalism in the same way. Like the tapes, each holds a special importance to understanding the story of The Witness as each conveys a unique way to interpret reality. To find these videos, the player must first find the hidden theater that allows them to view the videos; from there, they must solve six difficult puzzles on the island that unlock the corresponding videos. The videos once again display the minimalist storytelling that The Witness exudes at all points.

Once the player unlocks a video, they may return to the theater and watch it. The process almost exactly parallels that of the tapes, but with the addition of visuals. As the video plays, the player is introduced to the speaker’s specific worldview, and once it concludes, they leave with no information as to why it held any significance to The Witness’s story. Like with the tapes, the game elects to restrict the information given to the player, encouraging them to determine why these tapes matter to the overall story. In the same way that the tapes did, the videos use minimalist storytelling techniques to urge the player to contemplate the value of individual ideas for themself by presenting as little information as possible.

This picture depicts the theater where the player can watch the hidden videos.

A Lack of Context

Now that we’ve analyzed how The Witness uses minimalism to present its story, we must explain how said minimalism inhibits the player’s ability to recognize that a story exists. Remember: The Witness is a game of ideas. To convey these ideas, it applies minimalism in all aspects, be it gameplay, world, or presentation; through this minimalism, it hopes to encourage its players to think critically about the ideas they encounter and discern the importance of those ideas in the larger story. However, such extensive minimalism creates a situation where, in providing as little information about the story as possible, the game prevents the player from determining whether it even has one. The game fails to provide context for the inclusion of its various story elements, confusing the player about their purpose.

The Importance of Context

Understanding how The Witness errs requires that we first understand another key aspect of storytelling: context. The value of contextualization in minimalist storytelling cannot be understated.

Contextualization refers to the establishing information for the game’s story content. For instance, a game’s world heavily contextualizes its story through the development of the environments, the non-player characters, and the backstory of the world—these are collectively defined as world-building. Try imagining one of your favorite video-game stories occurring without the backdrop of its established world—seems a bit odd, doesn’t it? The characters and plot simply wouldn’t make much sense because the story’s world explains the traits and actions of the characters and the events of the plot.

Without this information, the player cannot discern why, where, or how the story occurs, so context is key. Allowing the player to view the story and its events as a product of the game’s world and characters, contextualization provides the reasons for the story to exist.

Game Design

With the importance of context explained, we can now consider how minimalism removes context from The Witness. Because of the extreme nature of its minimalist design philosophy, The Witness lacks context for its many story elements. Three major design choices—all of which reflect minimalist storytelling techniques in video games—compound upon one another to create a problem where the player can’t determine whether a story exists. Through the confluence of a non-linear structure, a non-verbal presentation, and a deliberate choice to make much of the story content optional, The Witness removes the context necessary for its story to be discernible by its player.

First, non-linearity prevents the player from understanding the purpose of certain story content. The island of The Witness grants the player freedom to explore its environments in any order they wish. (Some areas of the game require the player to have visited prior areas to learn new rules for the panel puzzles, but they generally serve as end-game challenges.) Not all areas must be completed to finish the game; once seven have been finished, the game allows the player access to the final area, where they can then complete the game. This non-linear structure embodies minimalist storytelling: it provides the player the freedom to explore the world, and thus the story, of their own accord without providing them much information on where they should proceed.

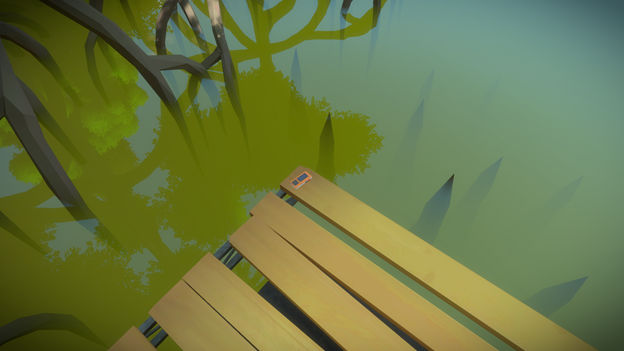

In another instance of hidden imagery, the flowers on this piece of wood only appear in the glare of the sun.

This design choice works against The Witness’s storytelling. Because the player can explore the world in roughly any order, they can encounter the game’s ideas in roughly any order as well; assuming they know the cassette tapes exist, the player may encounter them and their ideas in any number of different orders, which exacerbates an issue of inconsistent exposure to the game’s ideas. Since the player can proceed through the story as they wish, the game cannot control how they experience its ideas, be it through the tapes, puzzles, or videos. As a result, the tapes that the player does encounter appear out of place. From the player’s perspective, it’s as if there were no distinct reason for them to be where they are. Non-linearity removes the context for the tapes being in the world.

Second, non-verbal communication prevents the player from understanding the purpose of the game’s story content. In an interview with The Guardian, Jonathan Blow claims, “That’s the experiment of this game: just don’t use language at all.” Blow’s words here explain his intention of using non-verbal communication as a form of minimalist storytelling. On the positive side, this choice provides the player with much room to interpret the ideas that the game presents; on the negative side, it also creates an issue where the player doesn’t interact with the story in the way that the developers wanted them to.

Since the player doesn’t know the developer’s goal, they can easily overlook the purpose of certain gameplay or story elements. For example, the player never learns that the panel puzzles represent interpretations of reality. This lack of communication prevents the player from interacting with the game’s story and world as the developers intended since the game never implies those intentions; it also leaves the player to discover many of the game’s hidden mechanics—the tapes, videos, and environmental puzzles—on their own, as the game never states that these elements exist. Blow’s goal of telling a story non-verbally restricts the player’s ability to recognize The Witness’s story because the player can never understand what purpose certain aspects of the game serve. Because of this non-verbal communication, the context behind these story elements goes unexplained.

This screenshot shows another example of the environmental puzzles. To notice this one, the player must recognize the similar colors and the circular object.

Third, optional content makes the player wrongly infer that the story content isn’t actually necessary story content. In this regard, the most detrimental choice on the part of the developers was to hide aspects of the story in the environment because it easily allows the player to completely miss these story elements. Remaining wholly optional, the cassette tapes, the videos, the environmental puzzles, and the hidden images, all of which play an important part in presenting many of the game’s ideas, may never be discovered by the player because the developers deliberately obscured them in the environment. This form of minimalist storytelling ironically damaged the game’s theme of developing personal interpretations—the story of The Witness—by burying the parts of the game that emphasize it. Because the content is optional, the player reasons that it isn’t essential to the story, serving instead as additional and optional information, which defeats the purpose of their inclusion—the context of being key aspects of the game’s story.

Each of these design choices possesses issues of its own, but when placed together, they create a game that uses minimalist storytelling to the detriment of its own story. Because The Witness is non-linear, the player can encounter the game’s ideas in any order, and because the game uses non-verbal communication, they don’t know what they should do with these ideas. Because The Witness uses non-verbal communication, the player doesn’t know that its story is hidden in the environment, and because most of the game’s story is optional, they might never find important parts of it. The various minimalist design choices employed by The Witness detract from its ability to tell a story as they take minimalism to the point that the player doesn’t know if a story actually exists in the game. Each design choice contributes further to the lack of context for the story elements within the game.

The above screenshot demonstrates the game’s use of lighting to reveal the solutions to puzzles. In this case, the glare from the sun outlines the proper solution.

The Panel Puzzles

One aspect that illustrates the lack of context within the game stems from the panel puzzles. All story elements must possess context explaining the reason for their inclusion—in the case of the panel puzzles, that reason is to stimulate the development of personal interpretations by representing ideas. The game never informs the player of this intention so that they possess absolute freedom in their interpretations of each panel puzzle.

Through this minimalism, The Witness attempts to encourage its players to develop their own explanations of reality. While it tries to do so, The Witness ultimately fails to use the panel puzzles as a method of encouraging individual interpretation. The reason stems from the aforementioned use of minimalist storytelling, which removes all context for the panel puzzles embodying ideas.

Not telling the player the symbolic connotation behind each panel puzzle does provide them the most freedom in developing their personal interpretations; however, because the player doesn’t know that the puzzles represent larger ideas, they won’t consider them as such. The game’s tutorial establishes that in order to progress, the player must solve the panel puzzles; with that in mind, the player will progress through the game by proceeding from puzzle to puzzle to puzzle until they reach the game’s end. Since The Witness neither explicitly nor implicitly states that the panel puzzles carry some larger meaning, the player views them solely from the gameplay perspective—they are puzzles… and only puzzles. This minimalism removes all context to explain that the puzzles depict ideas.

Because the game refuses to even hint that the puzzles represent greater philosophical ideas, it removes any reason for such ideas to exist within the context of the panel puzzles. From the player’s perspective, the puzzles serve as the gameplay mechanic, not as a medium to convey the story, for they never receive any indication otherwise. In fact, were it not for the interviews with Jonathan Blow, few, if any, players would’ve entertained the concept of the panel puzzles as reflections of ideas. The extreme use of minimalism in this instance defeats the purpose of stimulating individual interpretation because the game never urges the player to consider the panel puzzles as a tool for it. There is no context that references that purpose because the minimalism removes that context.

This screenshot displays another environmental puzzle that can be found in the same room as the identical puzzle shown previously.

The Tapes and the Videos

Building on the idea that the game lacks context for its story content, the tapes and the videos, like the panel puzzles, demonstrate a lack of context to their inclusion, and both epitomize how the game uses minimalism to present ideas to the player. They remain hidden throughout the environment and quote/show historical thinkers expounding upon their interpretations of reality; the game doesn’t provide any information other than the quote/video in an effort to once again stimulate individual interpretation on the part of the player.

As a result of this extensive minimalism, numerous conflicting viewpoints appear among these cassette tapes and videos that go unexplained, illustrating the lack of context for their inclusion in the broader story. One notable contradiction appears among two cassette tapes that both comment on the accessibility of objective reality. In this case, one tape quotes Saint Augustine of Hippo stating the following:

[We] should hear not [God’s] word through the tongues of men, nor the voices of angels, nor the clouds’ thunder, nor any symbol, but the very Self which in these things we love, and go beyond ourselves to attain a flash of that eternal wisdom which abides above all things.

Augustine believes God to be the sole proprietor of truth. He views man, angel, thunder, or any item symbolic of God as a secondary medium—they don’t convey the words of God Himself and are thus inherently personal interpretations of His words. Therefore, he claims, by rejecting these mediums and listening to God directly, one can move past individual interpretations to see objective truth, the “eternal wisdom” he mentions. According to Augustine, one can understand objective reality, but only by turning towards God.

However, the game also presents a tape quoting Buddhist poet Yung-chia Ta-shih, who declares the following:

One reality, all-comprehensive, contains within itself all realities…. You cannot take hold of it, but equally you cannot get rid of it.

The “one reality, all-comprehensive” refers to objective reality, the complete truth of the world, and “all realities” refers to personal interpretations of reality. With this information, we see that Ta-shih believes objective reality combines all individual interpretations of it. Through this statement, he implies that all interpretations inherently display some aspects of objective reality. In this sense, he would agree with Augustine, who believes the secondary presentations of God (objective reality) reflect God Himself but that they don’t present the full, unadulterated picture of Him and His words.

Where the two disagree stems from their views on understanding the full picture. Augustine believes that one can grasp objective reality by turning directly towards God to attain his “eternal wisdom;” whereas, Ta-shih would disagree, claiming that one cannot reach objective reality at all.

Above is another example of the environmental puzzles. This one is especially hidden as it is camouflaged with the sand.

These two tapes, therefore, disagree: Augustine believes one can grasp objective reality and Ta-shih claims one cannot grasp it. Considering the game’s prior-established intention of encouraging players to think for themselves, this disagreement simply challenges the player to rationalize conflicting viewpoints, considering both ideas and determining what they believe to be correct. In this case, the game asks the player to answer the question: Can one comprehend objective reality? The disagreement itself means little on its own, but when analyzed in the context of the minimalist methods by which The Witness presents these tapes, it demonstrates an integral flaw in using said minimalism.

The key issue here stems from the fact that the game never outlines the intention of stimulating critical thinking with these hidden tapes. Were this intention at least implied to the player, then they would most likely consider this contradiction to be an exercise in critical thinking, but the fact remains that The Witness never informs the player of this intention. This very hands-off, minimalist approach to storytelling prevents the aforementioned exercise in critical thinking from occurring because as far as the player is concerned, they don’t know that they should be critically thinking about these opposing ideas; instead, these tapes present their opposing ideas without an inch of context for their existence within the game’s world and story.

From the player’s perspective, these tapes possess no established reason to exist, and considering the developers deliberately hid them in the environment, the player reasons that these tapes serve as an optional collectible, not as a key aspect of The Witness’s story, because they’re never told otherwise. The game provides no context to explain that they are story content. In the case of the tapes, the minimalist presentation removes all context for their existence in the game, thus defeating their purpose of promoting critical thinking.

In this screenshot, the shadow of a woman can be seen on a rock. A group of rocks and branches behind the player form the shadow.

Having analyzed the lack of context within the tapes, we can now turn to the game’s hidden videos and discover a very similar lack of context. For instance, in one video titled “Yesterday, Tomorrow, and You,” British scientific historian James Burke explains the following:

[The] reason why so many people may be thinking about throwing away those [reassuring crutches of opinion and ideology] is because, thanks to science and technology, they have begun to know that they don’t know so much.

Through these words, Burke expresses avid support of objective reality through science and technology, but understanding that conclusion requires some further context to the contents of the video. In the video, Burke discusses the power of knowledge to bring change into the world and argues that those with that knowledge today—scientists and technologists— pioneer humanity’s understanding of reality. He argues that scientific knowledge holds more value than forms of art since art reflects the artist’s worldview more than it reflects the world itself. To return to the quote, Burke explains that science has grown in popularity because people have realized that science can teach them more about reality than individual interpretation ever will.

Burke’s claims stand in stark contrast to those of spiritual teacher Rupert Spira, who in another video claims the following:

All that is ever known is a modulation of our own knowing presence, modulating itself in the form of thinking, sensing, and perceiving, and seeming to become a mind, a body, and a world…. In other words, we know ourself alone.

According to Spira, man can only understand that which he personally experiences. He argues that all thought and interpretation results from man’s personal perceptions of reality. Through this sentiment, Spira advocates for an individual interpretation of reality since, in his mind, objective reality cannot exist due to personal perception skewing it. For the remainder of the video, Spira expounds upon his own personal interpretation of reality and subjective concepts like awareness and love. The entire video reiterates this idea of individual interpretation of reality; whereas, Burke’s video emphasizes the objective scientific investigation of reality.

Like the example tapes, these videos express opposing viewpoints: Burke believes that one can comprehend objective reality through science while Spira argues that one cannot understand objective reality because one only knows oneself and their own experiences. Again, the contradiction itself doesn’t carry much significance when placed in the context of a critical-thinking exercise because then it serves to stimulate a rational analysis of both perspectives, urging the player to create their own perspective on the issue. But through The Witness’s use of minimalism, that intended exercise never happens because the player doesn’t know that it was the goal. Since The Witness does not provide a reason—context—for these videos to exist within the game’s world, the player questions their inclusion in the game rather than actively contrasting the two interpretations to reach their own conclusion.

If the game wants the player to critically evaluate these conflicting ideas, it must first outline the context for their inclusion so that the player understands what they should assess. Because the game never clarifies the intended effect, the player faces confusion over what they should do with these conflicting viewpoints, which negates the goal of promoting critical thought. The minimalist storytelling removes the context for including these conflicting ideas.

Another example of the environmental puzzles can be seen in the above screenshot. For this one, the player must position themselves in such a way that the flowers in this field align to form this shape.

These examples of conflicting cassette tapes and videos remain but two of many, many more contradictions found among the tapes and videos. One may accuse this analysis of cherry-picking examples to demonstrate these contradictions, but due to the sheer number of tapes, coupled with the remaining videos, one cannot possibly enumerate each and every one that exists within the game. Throughout the game, these contradictions run rampant, and due to The Witness’s excessive use of minimalism, the game never presents a reason to justify their inclusion, which only further confuses the player as to whether or not there is a story within the context of which such contradictions are meaningful.

A Comparison

Alongside The Witness, various other games have implemented storytelling through hidden items. For example, Dark Souls, a similarly minimalist game, engages in an analogous form of minimalist storytelling, and it has received immense praise for this kind of storytelling. Comparing the success seen in Dark Souls to the struggles seen in The Witness reveals the value in contextualizing a game’s story content.

The difference in success between the two games’ stories stems from the contextualization brought by Dark Souls’ world. In Dark Souls, much of the story exists in the item descriptions, requiring the player to actively search for the hidden story. As the player explores the world, they will find more and more items, be they weapons or consumables, whose descriptions further expand upon the game’s world and story. One such item description is that of the Tin Banishment Catalyst. Upon first glance, this item serves as a simple weapon for sorcery, but upon delving into its item description, the player uncovers a subtle detail about the game’s world. The item description reads as follows:

Above is the item description of the Tin Banishment Catalyst, which is the fourth item from the top.

From this item description, the player gleans a small additional piece of the world’s backstory. Demonstrating the profound effect of this seemingly insignificant detail, the player eventually travels to the fallen city of New Londo, where they see firsthand the flooding to which the item description refers. In fact, to proceed, the player must drain the water, which opens the pathway to the aforementioned Kings, whom the player must kill to continue.

By reading this item’s description, the player can understand why the city remains flooded, gaining a more comprehensive understanding of this area of the game’s world and its significance to the story. This method of minimalist storytelling has earned Dark Souls great praise within the gaming community, with many players actively digging into all item descriptions in an attempt to decipher the inner workings of the story.

Above are the dilapidated ruins of the city of New Londo, flooded to seal away the Four Kings, one of the game’s bosses.

The Witness is similar in the sense that the story is hidden throughout the world through the tapes, videos, and environmental puzzles, but it sees much less success in that endeavor. In Dark Souls, each item and its respective description receive contextualization from the world at large; they each have an explanation for their placement in the game’s world and contribute to the larger effort of world-building. As we see with the Tin Banishment Catalyst, the details in the item’s description provide extra backstory for New Londo and make the player’s interactions with the ruins more intriguing since they know that backstory.

In The Witness, the tapes and videos exist devoid of any context—there is no expressed reason for either to be present in the game’s world and no explanation as to how they contribute to the larger story. In the Augustine vs. Ta-shih example, the player doesn’t know how either idea fits into the game’s story, so they wonder why these ideas matter. The player will find a cassette tape in The Witness and question why it was placed there and what significance its ideas hold to the larger story; whereas, in Dark Souls, the player will find an item, and, through its description, they will learn more of the world’s backstory and characters.

Because The Witness embraces minimalism to such a great extent, it removes all context for its story, causing it to fail where games like Dark Souls succeed in telling minimalist stories.

Some Opposing Interpretations

In contrast to this article’s argument that The Witness lacks context for its story content, other interpretations argue either that the game does provide said context or that it doesn’t need context, making it a cohesive experience. Some of these interpretations pose counterpoints to the argument currently being made; however, they fail to account for the consequences of the game’s use of extensive minimalism.

One such interpretation is that the whole of The Witness serves as a Gongshi, or a scholar’s rock, in the form of a video game. Gongshi are rocks that have naturally eroded to a point of heavy distortion. Chinese scholars use these rocks as a means to develop new philosophies by analyzing the philosophical implications of their various distortions as products of nature—by doing so, they seek to better understand the complexities of nature.

The picture shown above is an example of a Gongshi. Source: The School of Life.

With this information in mind, one can draw parallels between Gongshi and the structure and presentation of The Witness. For instance, the panel puzzles, environmental puzzles, and cassette tapes across the game’s world seem almost unnatural, a corollary to the distortions of the Gongshi, and considering Jonathan Blow’s goal of presenting ideas through the puzzles, tapes, and videos, one can easily reach the conclusion that, like the Gongshi, The Witness uses these odd inclusions to promote the development of new philosophies about reality.

On a surface level, this interpretation of the game seems very plausible; however, when analyzed in the context of the extreme minimalism that the game utilizes, the comparison to a Gonshi becomes a false analogy.

First, in a Gongshi, the information presented to the viewer remains constant: the rock will remain the same rock with the same distortions for all who look at it. The value of the Gongshi originates from the potential to interpret said uniform information in vastly different ways—two people will see the same hole but will rationalize it differently.

In contrast, the information shown to the player in The Witness will vary on a player-to-player basis. For instance, one player may experience only the panel puzzles, missing the environmental puzzles and the cassette tapes; a second player may find some of the tapes alongside the panel puzzles but never discover the environmental puzzles (this describes my initial playthrough of the game); a third player may uncover all three and avidly search to find every one. Each case sees the player leave with a different level of exposure to the ideas the game presents, which can produce vastly different interpretations like the Gongshi do. Unlike the Gongshi, these different interpretations originate not from individual thought but rather from differing levels of exposure to the ideas in the game. This issue results from the game’s implementation of extensive optional content, a particular minimalist design philosophy.

Second, a scholar dedicates the majority of their time with a Gongshi to interpreting its nuances, not gathering the information that it contains. However, in The Witness, since most of the game’s ideas remain in cassette tapes and videos hidden across the island, the majority of the player’s time with the game will be spent searching for those tapes and videos to gather the game’s story. Due to The Witness’s use of minimalism in this instance, the game diverts the player’s attention from deciphering the ideas it presents to continually searching for those ideas. In this way, it differs greatly from the presentational structure of a Gongshi.

As a product of its extensive use of minimalism, The Witness cannot function as a Gongshi equivalent because it doesn’t convey information in the same way that a Gongshi does.

Here is another perspective illusion where, from the right angle, markings on a group of rocks form a woman’s hair.

A second opposing interpretation of the game posits that The Witness seeks to emulate the process of encountering ideas in real life. Like in real life, in The Witness the player explores the world, encountering ideas randomly without much reason to explain why they encounter them. Thrusting the player into an unknown world without any explanations, the game parallels the human experience: being placed in a world you hardly understand and seeking to learn about it. To rationalize the mysteries of the world, humans turn to each other for guidance, and it may be that the game hopes that the player will consult other players, be it in real life or online. To return to the Time interview, Jonathan Blow himself comments on this interpretation of the game, stating, “There’s a metaphor for being a person in the real world just trying to understand ‘What is the truth about where we are?’” Based on his comments, Blow apparently intended for the game to simulate the real-life experience of trying to understand the world.

One could consider this interpretation to be eminently plausible. However, two flaws exist in it.

First, The Witness doesn’t provide enough context to justify such an interpretation. The player never faces any sort of hint that the game emulates a real-life experience of trying to understand the world. The player begins the game with the baseline assumption that The Witness is a video game, not a simulation of real life. Since no information within the game alludes to said simulation, the player will never alter that assumption. If the game had provided context that established that it intended to mimic real life, then the player’s experience would have differed greatly, but because the game doesn’t even imply so, the player won’t interact with the game as if it were a simulation of real life.

Second, reaching the conclusion that the game replicates real life requires the player to consult sources outside of the game. The most prominent piece of evidence in support of the interpretation comes from Blow’s comments in the Time interview, which one would have to actively look for. Someone who simply finishes the game and moves on wouldn’t reach the conclusion that it mimics real life because the only evidence supporting that interpretation originates from material outside of the game itself.

Based on both of these points, the interpretation that the game imitates the real-life experience of trying to understand the world does not hold water.

Above is another hidden image found in the game’s world. In this example, the branches of a dead tree align with a cloud in the background to form the illusion of a tree with white leaves.

A Possible Solution

Because The Witness utilizes conflicting minimalist design philosophies to tell its story, it ultimately fails in that endeavor. However, a possible redesign of The Witness could maintain the game’s minimalist goals while also telling the story in the way that it wanted.

The primary issue with the game’s story originates from the lack of context behind many of its included elements. Solving this problem requires one major change in the game’s philosophy: make almost everything mandatory. As it currently stands, the player can encounter the ideas present in the game in any order or may never encounter them at all, and either way, they don’t know what purpose these ideas serve. If the game followed a structure that exposed every player to the same ideas in roughly the same order while ensuring that they understand the purpose of those ideas, it would succeed in its goal of encouraging the player to think for themself.

Consider the following hypothetical redesign: The Witness is a linear game. It occurs on the same island, but instead of allowing the player to explore, it progresses them through the island’s regions in a specific order. Beginning with a tutorial region, the game presents the player with an introductory example of a panel puzzle, an environmental puzzle, and a cassette tape. That cassette tape contains a quote that in some subtle way or another tells the player to consider the implications of the game’s content in terms of the larger picture of reality. After being exposed to the major philosophical content of the game, the player proceeds to the next region. In each region, the player completes panel puzzles, but along the way, they find cassette tapes deliberately placed before them and environmental puzzles hidden in, what else, the environment. These cassette tapes contain the same quotes from historical thinkers as in the normal game. At the end of certain regions, the player is rewarded with one of the videos, which remain the same as in the normal game. Continuing from region to region, the player eventually reaches the end of the game, which remains the same as in the normal game since the plot of being a playtester also remains.

The above panel puzzle is what many fans of the game consider to be the most difficult puzzle.

This redesign of The Witness would, in theory, solve all issues that result from its excessive minimalism. By being a linear game, the developers could ensure that all players experience the same content, mirroring the Gongshi. Through the use of a controlled tutorial area, the game can display to the player all major content within it—the panel puzzles, environmental puzzles, and cassette tapes—and imply their larger storytelling purpose of presenting ideas by using the example cassette tape. Deliberately exposing the player to the cassette tapes and videos as they progress through the game will guarantee that they encounter the ideas as the developers want them to and (hopefully) develop their own interpretations of said ideas. Maintaining the game’s core minimalism, this scenario would still be non-verbal and leave much room for interpretation, but unlike before, it would parallel a Gongshi by providing the exact same content to each player. Now, instead of focusing on searching for the ideas, the game would emphasize the interpretation of said ideas, and it would retain its minimalist storytelling techniques.

Successful Minimalism vs. Unsuccessful Minimalism

As evidenced by the issues with The Witness, minimalism in video game stories runs the great risk of causing the player to question if the game even tells a story. In The Witness’s case, using three heavily minimalist design philosophies in conjunction with one another created such a scenario. But where The Witness fails, other games succeed, and by comparing these games and their successes and failures in using minimalist storytelling techniques, we can further appreciate how context plays an important role in telling a minimalist story.

Dark Souls

Dark Souls’ use of minimalism has already been addressed in this analysis, but much of value can still be learned from its success in telling a minimalist story. The story in Dark Souls avoids directly presenting information to the players: the dialogue is vague, and numerous aspects of the story, including the backstories of the bosses, non-player characters, and world, require delving deeper into the game’s content to understand. Normally, this excessive minimalism would pose an issue for the story, but Dark Souls assuages this issue through its brilliant use of item descriptions.

From Dark Souls 3, this item description explains one of the game’s healing items, known as Embers. The player character in the game is one of the “Unkindled,” an undead being, and consuming one of these items grants them humanity until they die again.

Although the player can infer the details of the story by following the main storyline, each item description provides more information about the backstory of the game’s world, characters, and events, and the game contextualizes this information through its excellent use of world design. Every item feels as if it were meticulously placed in the world so that it corresponds with the events and characters around it. Leaving the contents of the main story vague, the game encourages its players to investigate the world further to uncover more details about the story. Through this indirect storytelling mechanism, Dark Souls employs minimalism to great success.

The Witness attempts a similar form of minimalism with its use of the cassette tapes, but as explained, these tapes exist devoid of any contextual purpose within the game’s world. They present ideas that the game intends the player to contemplate, but due to a lack of communication, the player is instead left confused as to why these tapes even exist. Various aspects of the game’s story appear to lack significance from the player’s perspective as a result of its excessive minimalism. In this way, The Witness fails at minimalist storytelling; whereas, Dark Souls succeeds.

Shadow of the Colossus

Shadow of the Colossus (SOTC) avoids explicitly telling its story. Very little dialogue exists in the game, and it only serves to establish the basic goal of the protagonist, Wander. Although the game lacks textual storytelling, it more than makes up for it by employing both visual and auditory storytelling. As Wander travels across the forbidden land, he fights sixteen colossi to revive his dead lover, Mono. During these larger-than-life battles, the music sounds intense and action-packed to reflect Wander’s battle to save her; however, each time he defeats a colossal beast, the music becomes melancholic rather than triumphant. The colossi were completely passive creatures, and Wander proceeds to murder each and every one for his own selfish goals. The depressing music that plays as a colossi falls to the ground serves to emphasize the evil nature of Wander’s actions. These few examples represent but a few of the methods in which SOTC uses music to tell its story in a minimalist way.

The beast seen above is the first colossus that the player will encounter in the game. It is entirely passive, wandering aimlessly until the player decides to attack it. Swatting the player away like a fly, it never becomes overly aggressive.

Additionally, as Wander murders more and more colossi, the player will notice a visual change in his character: his skin becomes sullied, his eyes darken, and he develops horns. This progressive change forces the player to question the morality of Wander’s actions since it appears that he is literally becoming a demon as a result of them.

Another example of visual storytelling stems from the presentation of the colossi. As mentioned, the colossi are passive creatures—they simply wander the world without purpose. But a creature is not lifeless, and SOTC uses this fact to characterize the colossi. In the most notable instance, when fighting a small, bull-like colossus, Wander must scare it away with fire, which makes the beast visually recoil in fear. This detail remains very subtle, but it serves to demonstrate that the colossi are living beings and that Wander’s actions are certainly questionable. The game never explicitly acknowledges these visual details, but they remain placed directly before the player, who will most certainly notice them. Using minimalism in this way, SOTC conveys its story through music and visuals instead of traditional text.

These minimalist techniques succeed in the context of SOTC’s story. From the start of their journey, the player understands that Wander desperately wants to save Mono to the point where he breaks the law to do so. They understand that he must kill each colossus to save her. This contextualization causes the game’s minimalism to excel fantastically as each subtle detail gradually leads the player to see Wander as the real villain of the story.

This picture shows Wander pushing the bull-like colossus towards the edge of its battle arena by scaring it using fire. It falls off the edge, knocking its armor off to expose a weak point.

In contrast, The Witness fails to use either auditory or visual storytelling to its advantage. As the game has no soundtrack, it drops the ball on auditory storytelling. When it comes to visual storytelling, The Witness attempts to convey its ideas through visuals, but it once again struggles due to its extreme minimalism. The environmental puzzles and optical illusions serve as fine examples of visual storytelling through their emphasis on viewing the world from different perspectives, but the player may never encounter these examples since the game never acknowledges their existence. Due to the game’s determination to be as non-verbal as possible, it restricts the player’s ability to encounter the story. In this way, The Witness fails; whereas, Shadow of the Colossus succeeds.

Context Matters

We’ve seen how The Witness uses minimalism to convey its story, how that minimalism prevents the player from determining that a story exists, and how other games, in contrast, implement minimalism to great success. The determining factor here is context. A lack of context inhibits the players of The Witness from concluding that the game tells a story. Its various story elements—the panel puzzles, the cassette tapes, the environmental puzzles, the videos—don’t possess an established reason to exist within the game’s world or convey its story; as such, the player cannot reason that the game tells a story. Extensive minimalism created this lack of context.

From The Witness, we see how integral a role context plays in telling a story, especially a minimalist one, in a video game. Had The Witness provided the information to explain why its story elements exist within the game’s world, the player could have rationalized that the game had a story. Context holds incredible importance to games as a storytelling medium because the idea of considering video games as a means to convey a profound and unique story has only recently appeared. To most people, gamers or not, video games are just that: games, first and foremost. This reality means that video games must clarify that they are telling a story because otherwise, they’re just games. Providing the necessary context allows a game to indicate that it is telling a story and should therefore be treated in the same way as literature or art. If developers like Jonathan Blow want their games to be seen as profound stories, they must present the information—the context—to reveal that intention.

5 Comments

John · May 28, 2019 at 5:55 pm

I really enjoyed the article. There’s a lot to be unpacked with The Witness.

The Gongshi section was particularly interesting to me. I learned a lot there. It did make me wonder something too. Given that the content of The Witness isn’t random, wouldn’t that be enough justification to back up the interpretation of the game as a Gongshi? A person viewing a Gongshi might focus on the cracks on its surface, while another might focus on the color of the stone. Everything is present on the rock, but a person doesn’t have to engage with all of it in order to interpret it. Effectively, the parts that the person don’t talk about, don’t exist as a part of the interpretation. However, they’re still there, much like how the missed content in a game is still there.

Thanks again for the article!

Caymus Ducharme · June 18, 2019 at 9:21 pm

Hi, John!

Thanks for reading the article and sharing your thoughts. You pose a very interesting question about a perspective that I never thought of initially. The point you bring up seems to be a relevant counterpoint. The viewer of a Gongshi may very well decide not to analyze all aspects of it, and The Witness allows for a similar choice. However, I would like to point out that subtle differences exist with this comparison.

In a Gongshi, everything is present on the rock, as you say, and in The Witness, all of the content is present in the game. The difference arises because with the Gongshi, all the content is laid bare for the viewer to analyze, whether they choose to analyze every piece or not. Conversely, in The Witness, much of the content is deliberately hidden from the player, requiring them to actively seek it out. As I believe I mentioned in the article, The Witness places more emphasis on searching for the content, rather than analyzing it; whereas, a Gongshi is the exact opposite, focusing more on the analysis and interpretation.

The major factor here is choice. In a Gongshi, the viewer can choose not to interact with specific aspects of the rock while still having equal access to those other aspects, but in The Witness, if a player doesn’t interact with some of the content, it’s probably because they never found it. I must acknowledge, though, that choice still plays a factor in The Witness: a player may choose to search for every piece of content possible, or they may choose to ignore all of it. But the fact remains that because the content is hidden, the player doesn’t possess complete control over which content they can choose to analyze since they might never find some of it. For example, my initial interpretation of The Witness didn’t involve the environmental puzzles, but that wasn’t because I choose to ignore them; it was because I never found them.

As I mentioned in the article, each viewer of the Gongshi will see the same rock; however, in The Witness, each player may see a different rock, depending on what content they find. Based on this difference, I don’t believe The Witness accurately functions as a Gongshi.

Once again, thank you for reading the article, and I appreciate you sharing your thoughts.

Ryan · December 2, 2019 at 10:17 pm

Hi, Caymus,

This is an amazingly rich analysis of a game that absorbed and frustrated me in equal measure when I played it initially in 2016 (and when I’ve returned to it a number of times since), so thanks for that! At some point, I hope to teach a class in Writing about Gaming, and this would be an ideal example of a kind of scholarly/intellectual game analysis I suspect my students might not realize exists.

I still have a lot to think about, but I’d be interested in what you might think the game might have lost by being much more linear. It’s almost hard to imagine a version of The Witness that requires each player to go through every piece in almost the same order (since so much of the aim of the design seems to be to allow players to explore the game in the order they see fit).

In a sense, I’m not sure that the focus of the game is actually providing a story, though as you discuss, none of the other models for what it might be doing fit easily either. For that reason, I sometimes think we might need new models for what art games are doing other than preexisting artistic mediums (such as narrative). I imagine you might have thought/written about this at some point.

That said, the main elements that have always struck me the most about the game ate the following:

-the contrast between its incredibly inviting, almost candy-colored beauty and its often punishing difficulty;

-the way in which, for me at least, many of the puzzle types, while challenging, feel like work/drudgery rather than absorbing games (the entire desert area, much of the autumn forest);

-the lack of even momentary satisfaction or reward for solving most puzzles (since most simply activate the next puzzle); and

-despite all the frustrating elements, sheer wonder at the intricacy of the island’s design, given the environmental puzzles and structural elements (while I far prefer The Talos Principle as a puzzle gaming and story experience, The Witness is in a whole other league in terms of visual design).

Liam · June 20, 2022 at 1:41 am

I thought a lot of the interpretation came quite naturally, without needing signposting. I wasn’t looking at black and white as about racism or anything that literal, but the game seemed puzzles seemed to encourage one way of thinking, then force you to see past that to get to the next stage. It reminds me of the game Go at times, where a sort of daoist thinking is encouraged, when is something the figure, and when is it background? when are you walling a shape in, when are you keeping it out?

Having the freedom to roam allows you to observe your own meta learning. When is it useful to try to brute fore a hard puzzle? when should you go back to an easier one to check that you haven’t made an erroneous assumption? The videos and Audio all tied in well for me, as they were about ways and perspectives on knowing and seeking meaning. The game to me feels like it is an invitation to explore yourself and the way you grapple with the unknown. Forcing it into a linear story would ruin it for me.

Vladimir · April 20, 2023 at 12:07 pm

Thank you for the study! I think this review is a bit harsh on minimalism. I don’t see a lot of examples to back up its claims.

You also base your claims on interpretations that are not necessarily correct. The quotes within the game

“[We] should hear not [God’s] word through the tongues of men, nor the voices of angels, nor the clouds’ thunder, nor any symbol, but the very Self which in these things we love, and go beyond ourselves to attain a flash of that eternal wisdom which abides above all things.”

and the quote

“One reality, all-comprehensive, contains within itself all realities…. You cannot take hold of it, but equally you cannot get rid of it.”

complement each other, and so effectively help the player communicate ideas. You mention that both are a contradiction of each other, which are not.