Where the Water Tastes Like Wine (WTWTLW) paints a true picture of the United States during the Great Depression, with the hunger, the dust, the unemployment, the hippies, the talking wolves, and the wisecracking ghouls.

I stand by what I said.

The game is clearly a work of fiction. But it’s one that is deeply concerned with what is true, down to explicitly identifying 16 stories among its 250 as true. These 16 are distinguished from the rest both mechanically and narratively, but they face a certain irony: the game wants these stories to be true both within and outside of the context of the game, but it displays the real-life author of each of these 16 every time you encounter the person telling it. So, the stories pull between being fictional and being true. In doing so, they tell a powerful message of how America has always fallen short of its promises, and yet how, perhaps, that isn’t such a dismal statement after all.

So, sit a while by the fire with me as I tell you how WTWTLW uses its other 234 stories to set up a pattern that informs how we should interpret the main 16, and how that all relates to the history of the United States.

Game Overview

Before I delve too far into the meat of the Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, it’s worth explaining how it actually plays.

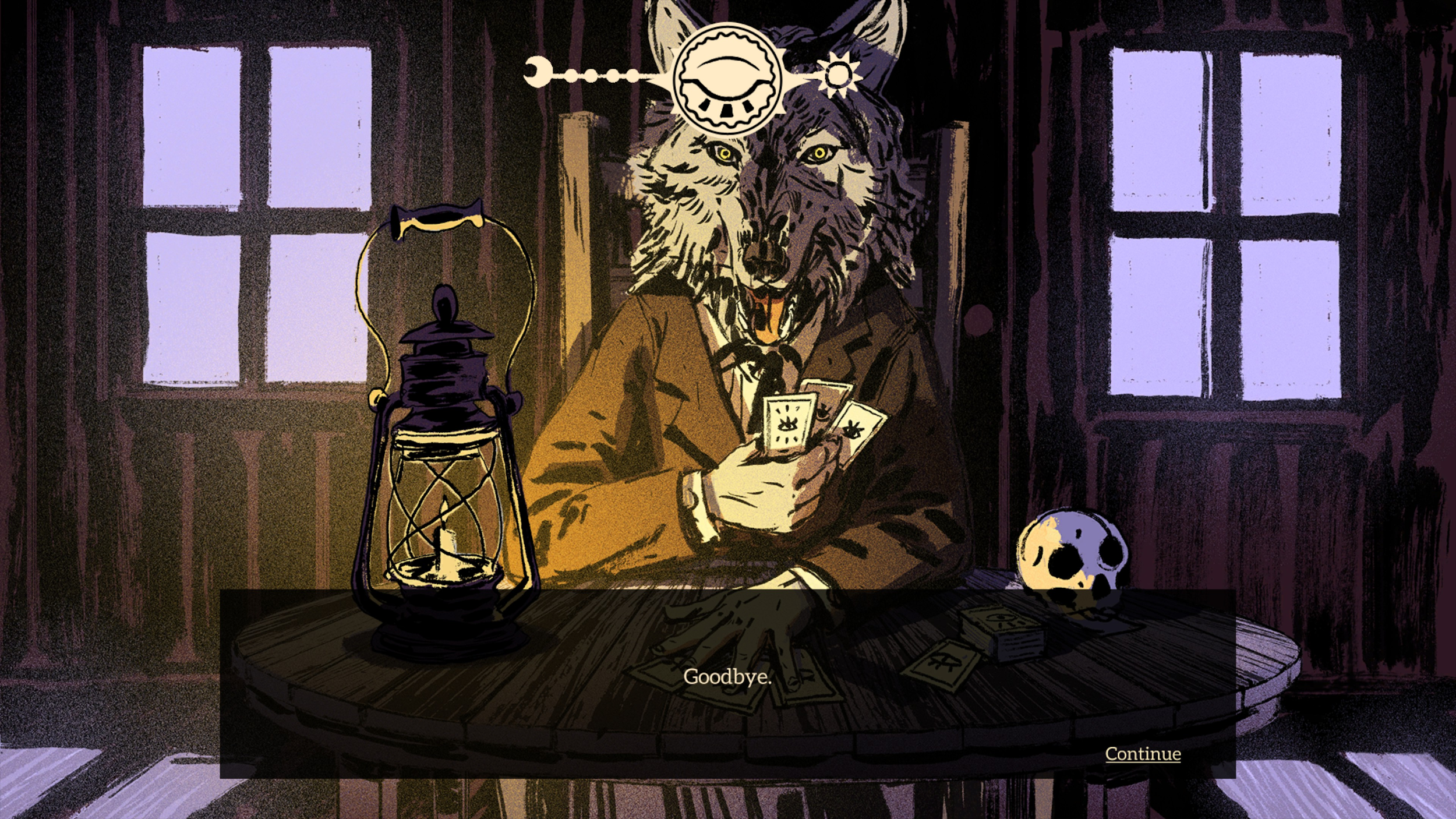

After a particularly high-stakes poker match, you, the player, surrendered your soul to a talking, suit-wearing wolf. This Dire Wolf (who is voiced by Sting) gave you a debt: to find and carry stories.

The goal of WTWTLW is to pay off this debt. The gameplay can be divided broadly into two phases: Wandering and Campfires.

During the Wandering phase, you are a skeleton roving a map of the continental U.S. (don’t worry, most people don’t realize you’re a skeleton). You can travel on foot, hitchhike, or catch a train.

Along the way, you need to manage health, rest, and money, all while finding various marked vignettes. These are very short stories about things that happen to you. Some are mundane (the gay couple in a lighthouse on Cape Cod who give you shelter from a storm), and some are surreal (the fish who was filleting a man).

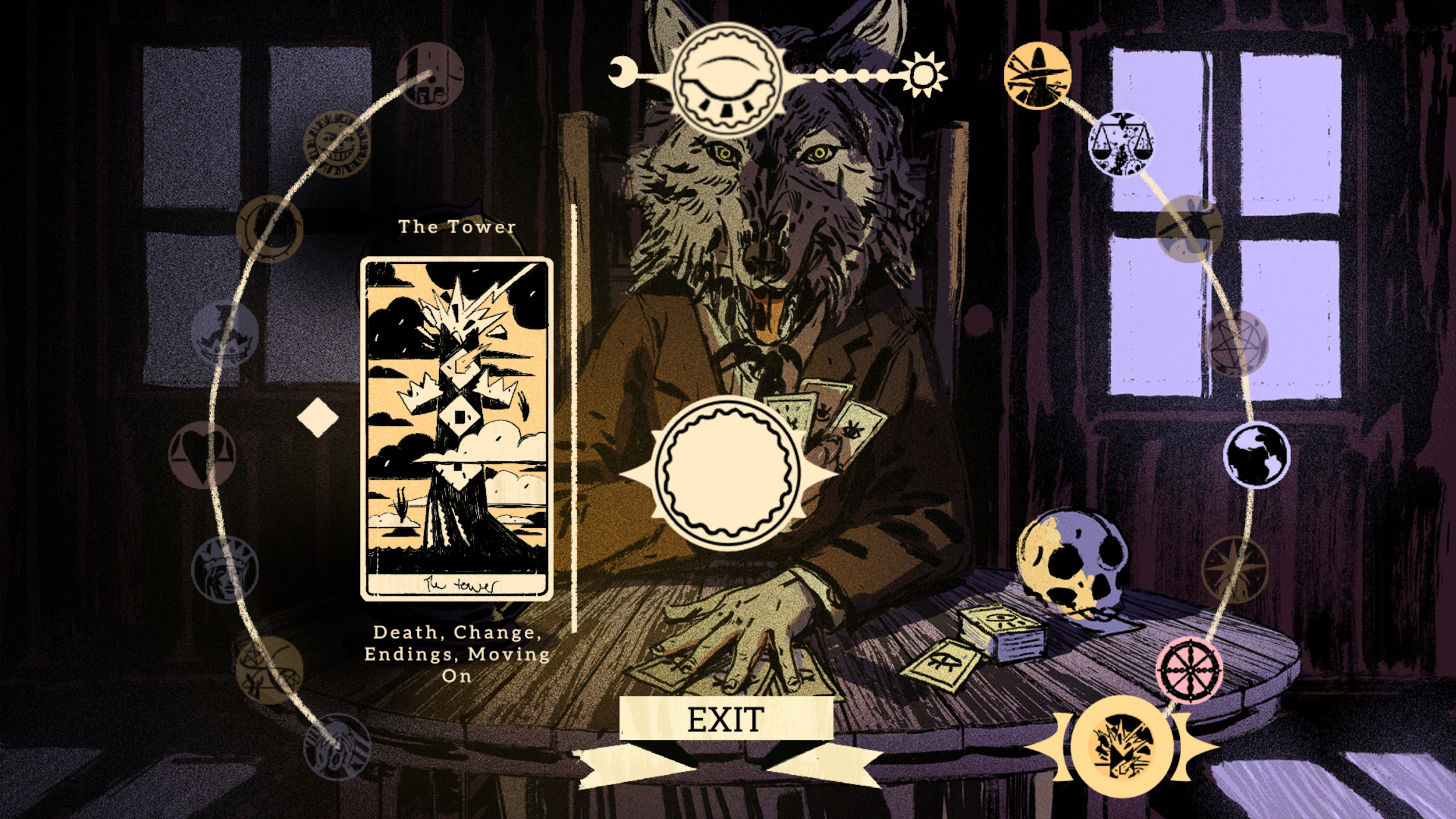

These stories are classified according to 16 themes represented by tarot cards, a framework for which the game offers no justification other than that the Dire Wolf really likes tarot. They range from tragic, to hopeful, to thrilling, to scary, to funny.

More importantly, as you progress through the game, these vignettes will grow. Tell them at a campfire, and you can run into them again later—however, you’ll find that they’ve been altered, usually to become more extravagant and unbelievable. These expanded versions replace the original story in your inventory and become more powerful[1] at the campfires.

The map of America. A campfire is visible in the distance.

At a Campfire, you’ll meet one of the 16 NPCs whose life stories I mentioned earlier as explicitly “true” (I’ll introduce you to them all in detail a bit later). They ask for a particular kind of vignette (tragic, hopeful, etc.) Comply, and in return, they’ll tell you part of their life story, focused on the tarot category of the vignette you told. These tales are then added to your collection, and they act as a kind of failsafe in later campfire visits: they will always fit the request of the asker.

Once you’ve finished a night (5 story requests), the NPC will move to a different campfire, and if they trust you enough, their story will progress.

Anyway, that’s enough time explaining the world my story takes place in. Let’s rewind to the very beginning: to that time I made a poker bet with a wolf.

A Trick of the Cards: The Dire Wolf

My day went south when I was playing poker up in Maine. It was just me and this other guy, and we were all in. I’d bet my word as collateral, since he had more money than I did, but I couldn’t lose! I had a Royal Flush, ace high. Best hand in the game.

Well, I don’t know if he cheated or what, but next thing I knew, he had my flush, my hand was replaced with some tarot cards, and my opponent revealed himself to be a suit-wearing wolf.

The Dire Wolf (that’s his name) is kind of an enigma. He is certainly invested in the U.S., but he exists outside of it, spatially and temporally. You meet him at the beginning of the game, at the end, and any time you die in between. Still, within the confines of your quest, he is the ultimate authority. Here’s what he told me at the beginning of the game (even before he turned me into a low-poly skeleton). This is the cost of my ill-advised bet in blood, according to him:

You see, this land is built on stories. It’s one big story, this country, woven of many small ones. Few of the small ones are strictly true, and the big story is mostly a lie. All the stories and songs and myths and legends start somewhere… with a seed. As they’re told and re-told and passed around, they grow and change to become the stories we know. To pay your debt to me, you’ll be carrying stories. Finding the seeds, first, and then spreading them. Telling them onwards so they can begin gaining strength. This is no light task – stories are heavy. Most of the stories you’ll find will be small seeds. They might be true, but they’ll grow wild and unbelievable with the telling. The more important stories are the true ones – the ones people will tell you about their own lives. Those often get lost in the weaves of the big story. The more true stories you can find and tell, the more you can weave that truth into the big story. Tarnish it a bit, perhaps, but isn’t a dingy and battered truth better than a shining lie?

He sets up a three-way trichotomy, between “small seeds,” which I’ve been calling vignettes, “true ones,” which I’m calling tales, and “the big story,” which is the entire history of the U.S.A. The relationship between these three classes of stories is as follows:

- The big story is made up of a combination of vignettes and tales.

- The tales are more important the vignettes.

- There are vastly more vignettes (~235) than there are tales (16).

- The quantity of vignettes tends to obscure the value of the tales.

One tidbit is particularly interesting: the Dire Wolf regards the tales as true stories, while the vignettes have a much looser relation to the truth, growing and expanding. Within the context of the game, this makes perfect sense. The tales do not undergo the same development from firsthand experience to folk legend as the vignettes all do, and therefore they can be called true.

However, I’ve found that the relationship between WTWTLW and its truth is somewhat more complicated than even the Dire Wolf thinks it is. The game tends to blur the boundary between player and avatar, and, by extension, the boundary between the world of the game and the real world.

For example, the final stage of one vignette is just “The legend of Casey Jones.” Nothing in the game would possibly allow the character to know that Casey Jones really was a railroader who died trying to stop his passenger train from running into a freight train in 1900, much less that he was turned into a folk ballad.[2]

A second instance of this blurred relationship between player and avatar is the Dire Wolf himself. As I said, he (and, by extension as his debtor, you) appears to be outside of the flow of time and space to which the rest of the game is subject. As a result, he operates in a way more akin to the player themselves: coming in and out of the world at convenience, controlling its flow as a result. (In this way, the Dire Wolf is strikingly similar to The Outsider in Dishonored.)

There is a third, much stronger blending of the line between the player and the avatar which occurs in the final meeting between you and the Dire Wolf—but the details of this meeting would be spoilers, which, out of courtesy, I won’t share. Just because you’re sitting here with me, doesn’t mean I have to give up all my secrets!

Because of the blurring of the boundary between the game world and our reality, it is reasonable to extend the Dire Wolf’s claims of truthfulness beyond the game as well—especially since the Dire Wolf himself straddles the gap between those worlds. The tales, then, are not only meant to be “true” in the way that stories can be in any fictional world, but they’re meant to be “true” in the player’s reality as well.

In that case, it is highly peculiar that these tales, which list their real-world author at the start of every meeting with the NPC in question, are called “true.”

Quinn’s life isn’t even the work of a single person! As much of a tearjerker as his tale is, it feels weird to call a story like this “true.”

I had to ponder this for a while, but the Dire Wolf’s claim that the vignettes start off true and then become wild sparked an idea: perhaps the vignettes were more closely related to the tales than is first suggested. Maybe, just maybe, the vignettes and the tales work under the same rules, and just started from different sources. If that were true, well, those rules would be nothing less than the pattern of the largest American story! And if I know that … well, that should let me find the truth of this whole adventure I got conned into.

That idea proved to be right. Let me explain.

From Life to Legend… or The Other Way Around.

Once the next morning came and the Dire Wolf sent me on my merry way, I quickly started to meet other people. I only get robbed a couple of times (and shot at once), but let me tell you, the amount of things that can happen in a couple of hours is truly staggering.

All of these encounters make up the vignettes. Vignettes are the most common type of story that I (and any other player) came across during the game. These are sometimes normal, sometimes outrageous, but some of them show a trend that is crucial to understanding the truth about WTWTLW.

The most important feature of the vignettes is that they expand and are altered over time. Each vignette has 3 versions. As an example: the story of the couple in the lighthouse becomes the story of the lighthouse where lovers can find solace, which becomes the story of the lighthouse which will only light in the presence of true love.

A scene from one of the vignettes. I believe this was the time a couple of ghosts threatened to kill a symphony orchestra for being just terrible. It was really funny; I’ll tell you about it some other time.

The final stage of the vignettes is often the most interesting. You know how I mentioned Casey Jones just a moment ago? Well, Pecos Bill, Paul Bunyan, and Ichabod Crane (or at least the Headless Horseman) all make appearances in the game, too. Each of these figures appears in the vignettes, with their own 3-stage progression. But, of the three versions, we players outside the game know the last, most extravagant one best, and the game knows this.

For Ichabod Crane, the third and final version of the vignette is called “The legend of Ichabod Crane and Sleepy Hollow,” referring to Washington Irving’s short story. I ran into a German man with an injured neck and a face hidden by his hat and cloak, and that man became the Headless Horseman. Poor Ichabod never appeared until the final iteration of the vignette when I experienced it! As a result, the story seems to have completely lost the only character the player would recognize! The story with named characters and a title that doesn’t immediately reflect the player’s experience within the game’s world (i.e. the third version of the vignette) warrants the most explanation, but is given the least. Even the middle version of this story at least said that the Headless Hussar haunted a town!

Similarly, the true story of Pecos Bill within the game’s fiction is that you saw him ride into a tornado, then later met him with a nervous horse and a (pet?) rattlesnake. That’s all. But the in-game summaries of the vignette’s third level don’t tell you what happened when Pecos Bill rode a tornado across America (he created Death Valley, if you’re curious).

There’s really one reasonable explanation for why the most expanded versions of so many vignettes are given the shortest summary: the oldest versions of the stories (i.e. the ones that were produced first in our world)… are the most outlandish. On some level, this is so obvious as to be absurd: yes, Washington Irving wrote The Legend of Sleepy Hollow before 2017. But, remember: the game consistently blurs the line between the fiction of the game and the outside world. This matters, because it means the explanation “it’s just part of the game’s fiction that the most outlandish vignettes are the youngest” doesn’t quite ring true.

Instead, occupying the same blurred space as so much of this game, the mundane versions of the vignettes seem to be a kind of back-formation: an artificial construction of the mundane from the outlandish. So, to lay out the Sleepy Hollow vignettes fully: The tale of the headless German in the mid-Atlantic -> The Headless Hussar who haunted the town of Sleepy Hollow -> The legend of Ichabod Crane and Sleepy Hollow. The last of these three vignettes has all the of elements we are familiar with from Irving’s book, and the earlier vignettes intentionally pare the plot down to one ambiguous meeting on the roads of Virginia.

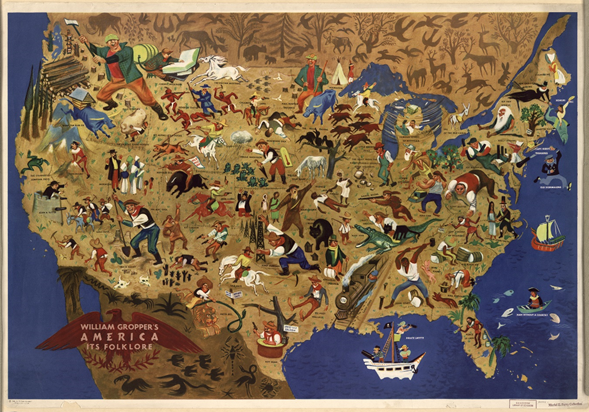

A map of American folk stories, by William Gropper.

This mechanism of back-formation is supported by the game, since the “lived” vignettes—the ones about things that your avatar actually experiences—are a mixed bag. Some of them are perfectly believable, but the one about the 3-headed grackle who was constantly hungry? Or the talking raven who tried to peck my eyes out as a joke? Not so much. In those cases, the expanded vignettes are so outlandish that it’s impossible to make the lived vignettes truly “mundane.” The player’s avatar still experiences all of them, but the mix of the natural and the preternatural in the lived vignettes is evidence that these versions were written after the third versions, which are more universally outlandish.[3]

An interesting side-effect of how these vignettes were written is that the game disincentivizes the truth when it comes to these stories. The lived vignettes are mechanically the weakest: they progress the stories of the NPCs quantifiably less than the more outlandish versions do (trust me, find the upgraded stories. You’ll want those for the later parts of the game). On the other hand, the actual folk stories are false both in the player’s memory and in the Dire Wolf’s estimation, resulting in no more regard for the truth of the story from that angle.

Now, I could continue about these for much longer, but the vignettes aren’t my focus. I applied this thought process from the vignettes to the tales, in order to see if it explained how the tales were counted as true (spoilers: it worked). Here’s what I learned.

The Answer To The Ultimate Question of Life, the Game, and Tales

Now we come to the crux of my whole story: What about these “true” stories (at least, true if you trust the Dire Wolf)? Well, it turns out they are themselves back-formed stories, just like the lived vignettes. But, instead of folk stories, they’re historical tales distilled and condensed into a single person’s life.

At this point, I should probably introduce you to the 16 NPCs I told you about earlier. Well, here they are:

There’s not a lot at first that stands out as unifying this group, which is, I think, intentional. They’re from all over the place. Different races, creeds, economic statuses, and physical locations. They weren’t even all alive at the same time! Dehaaya and Shaw are probably the oldest, since Shaw remembered being a slave and Dehaaya was a child during the Long March of 1864. Meanwhile, Rose is from the post-Vietnam era, in the 1970s.

Now, I met all of these fine folk all during my time in the game, several times, and in no particular order. I met Quinn first, but Dupree’s tale was the first I completed. They are all scattered around the map at the same time, at least from my view. Time certainly passes for them, sometimes years, but it worked differently for me. The Dire Wolf told me that I view time differently because I work for him, and Rose mentioned sensing something similar.

But, remember, WTWTLW doesn’t prioritize true events within the context of the game. Even without a mystical justification, compared to a fish filleting men, it really isn’t hard to just accept that two people a century apart could exist in the same place.

Ray. He’s a cowboy traveling around the American West from the late ‘30s and early ‘40s. He isn’t such a big fan of the government, which he talked to me about pretty often.

But even apart from the atemporality of these people, we aren’t any closer to making their biographies true. They’re still fictional stories, something that is occasionally really strongly emphasized (for example, by showing the author of the tale each time you visit one of our 16 friends).

Well, here’s a different explanation for how these tales achieve “truth”: we already know the game back-forms folk stories into vignettes; it turns out that the same is true of these tales. After all, if these stories are to have any claim to truth, they have to come from somewhere, and that “somewhere” is true history.

Dehaaya, Franklin, and Mason are telling in this regard. Their stories touch on specific moments in American history: the Long March, the unionization of the Pullman Porters, and the Bonus Army of 1932. The correlation between these historical moments and the stories within the game indicates that WTWTLW does, in fact, back-form narrative histories into tales. This offers some insight into what makes the tales themselves “true.”

The tales in the game are “true” not because the details in them actually happened (though they are often completely plausible). Rather, they are true because they incorporate historical fact from the perspective of the people who were impacted the most. They are written around the known experiences (recorded in ink and paper, or by mouths and minds) of the people who aren’t represented in textbooks (at least, not in the ones from when I was in school).

From this perspective, we can now see what unifies the 16 NPCs: their disadvantaged status in history. Hearing their stories, I saw how similar they all were. They suffered under an oppressive system, but they kept hoping and struggling to various ends. That tragedy and endurance draws a thread through the entire premise of the game. As you suffer and laugh and witness horror and hope in the game, you hear the same from everyone else, backed by the historical record.

That pain and joy is the backbone of the American tall tale.

This is the genius of WTWTLW: The historical grounding, and therefore the truth surrounding the game and its stories, is only visible because of its ahistoricity. Without the vignettes hinting to the back-formation process used by the game, and without the Dire Wolf conflating the world of the game and the larger world, it would be impossible to extrapolate the tales within the game to the larger American experience. But, since the game did include these things, the themes of the game echo out into our own lives and memories.

Ending

Well, Reader, now my story has almost ended. But, the Dire Wolf left me with one more question: All those people I met, they were searching for something, and so was I. He asked me if I found what I was looking for. And I don’t know that I did. I certainly found something, playing that game, and something valuable at that.

But, my road stretches long before me, and the morning is near.

Special thanks to Johnneman Nordhagen and Dim Bulb Games for providing the copy of the game used for this analysis.

- I here use “more powerful” in a strictly mechanical sense. The hidden thresholds required to advance the 16 tales increases with each chapter in those stories. Higher level vignettes, however, add more progress to these hidden progress meters than lower level ones. I discuss the narrative implications of this down below. ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casey_Jones. The information there largely comes from the now-archived Casey Jones Museum website. One of the versions of the ballad can be heard here. ↑

- Again, it’s worth mentioning that this is referring to the actual writing process for the game, and therefore to something in our world. ↑

1 Comment

Felix Weingardt · February 24, 2022 at 5:35 pm

I for my part never cared that much about the bigger tale.

Its the small stories that are important since they interact with the people on a more personal level. The way the player moves from one story to the next very much like a ghost his own involvement in the story more that of a witness than an actor. On the matter of truth it is my opinion that all stories in WTWTLW are true. They may not be a historical fact but they are still true. Even the big tale of America as a whole is true.When something influences people and become part of their perception of reality then such a thing becomes true.