The Hero of Time Project is an attempt to re-examine the narrative vacuum in the Legend of Zelda series between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, and to utilize the concept of fan fiction to logically fill in some of the gaps using information presented to us in existing lore.

The Hero of Time Project is an attempt to re-examine the narrative vacuum in the Legend of Zelda series between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, and to utilize the concept of fan fiction to logically fill in some of the gaps using information presented to us in existing lore.

Welcome back, our Legend-loving readers, to the Hero of Time Project, where we, the Know-It-All Brothers, are taking an analytical approach to telling the untold story of the final years in the life of Link, the Hero of Time.

If there’s one thing that can be said about the Legend of Zelda franchise, it is that its fanbase is among the most eager, rabid, excited, passionate fanbases of any out there (and we feel that we speak earnestly for the collective Zelda fanbase in saying that).

With a game series spanning over 30 years, selling nearly 100 million games,[1] it’s no surprise that the franchise has developed this sort of following. This level of dedication brings so many wonderful things, from fan art such as Damien Canderle’s rendition of an Old Man Link,[2] which played a large part in inspiring the Hero of Time Project; to (admittedly illegal) fanmade games and fanmade movies like Ember Labs’ collaboration with Theophany, relevantly titled Terrible Fate.

Another fan-made take on Link’s return to Hyrule after Majora’s Mask, Voyager of Time, by Brynna Giadrosich.

That being said, one of the biggest questions the developers face with each and every new game released is: how will the fans react to this? In writing Hero of Time, that has been one of our biggest concerns as well.

Telling a (Good) Story Using Fan Fiction

Fan fiction is a unique form of storytelling wherein canonical resources and information are lifted from a source material, and then used to construct a new story. Sometimes these new stories operate in parallel with the source material, and sometimes they operate entirely outside of it. The beauty of a fan-told story is that the fan writing it has the freedom to place it wherever he or she wants to in relation to the source material.

This, however, can be one of fan fiction’s greatest flaws as well.

A fan story may sometimes try to fill gaps in a series, but it may do it in ways that fans other than the author never cared about, explaining things these fans didn’t need explained, or serving as a self-insert wish-fulfillment story for the author alone. There are countless examples of fan-fiction storytelling like this, and most of them involve purpose-built mary sue[3] characters meant to represent the author achieving all of his or her own wildest (often sexual) fantasies.

One such example of fan-fiction which provides nothing but wish fulfillment: “Forbidden,” a “Harry Potter Has A Sister” fan fic, presented with pointedly honest commentary, at PoorlyWrittenFanfiction.

On the other hand, a well-written fan story can fill in thematic gaps that, when filled, allow the series as a whole to tell a more complete, more satisfying story. One such example of this is incredibly prevalent in our current media: Hollywood remakes.

Power Rangers, Total Recall, RoboCop, Godzilla, and the ever-controversial Ghostbusters were all remakes or “alternate universe” stories written by different authors than their original source material. The quality of these ranges critically from “dead-ass awful” to “better than the original” from person to person, but one could easily make the argument that this form of fan fiction typically strives to tell a great story, and to serve the source material by doing so.

To us, the most important qualifying factor of a great story, fan-made or otherwise, is the audience’s reaction: if the audience feels something, if their emotional response is triggered by a story, then that story has transcended words on a screen or ink on paper, and has become something deeper, something more profound. By affecting its audience, a story becomes a part of its audience. That became a mantra that we repeated over and over in our heads as we carefully blended pre-existing elements from Zelda lore along with new and inventive elements and characters—original content, or OC[4]—in order to create one cohesive story that is, hopefully, better than the new Power Rangers film.

The purpose of this project is to fill in some of the holes in the Zelda story while paying respect to both creators and consumers, and, most importantly, to tell a great Zelda story that the fans will love by treating our story like a genuine Zelda game in the way we constructed it.

This brings us to the question with which we began Hero of Time: how do you tell a great story that isn’t yours? How do you reconcile differences left by myriad writers over decades of game releases? How do you make changes and additions to a history that’s so well-loved by so many people without ruining the spirit of the source material?

This article aims to answer those exact questions. Here, we’ll begin by discussing what themes and foundations unify the Zelda games upon which Hero of Time is based. We’ll also explain how we approached the tedious prospect of adding original content to a well-loved fanbase (Spoiler Alert: Cold Steel probably does not make an appearance), touch on the storytelling mechanics of the series and how we’re employing them, and finally, we’ll explain how to evolve and develop the storytelling elements of a pre-existing franchise without completely ruining it for fans (DC Cinematic Team, we hope you’re reading this).

WHY ISN’T THIS WORKING?!

When we began thinking about how we could tell the Hero of Time story, we knew immediately that we had a big task in front of us. We had to figure out how to tell a really convincing and authentic Zelda story. In order to do that, we had to figure out what exactly it is that makes a Zelda game feel like a Zelda game. And in order to do that, we had to go back to the beginning. And not just the beginning of Zelda itself. We needed to take a look at the core genre of a Zelda game, analyzing it like the video-game DNA that it truly is.

Dawn of a New Era: The Origin of 3D Platformers

In the beginning, before anybody hated The Wind Waker, before anybody raced Dampé, and before anybody rage quit at the Water Temple’s puzzles, things were simpler. Reality was constructed of nothing but two dimensions and eight colors. It was a simpler time, a time of two-frame animations, of story-absent games, and of one, single button.

Then, on October 30, 1987, a gift was bestowed upon humanity by Hudson Soft: the TurboGrafx-16. This home video game console brought about a new era of gaming: the fourth generation, or simply, the 16-bit era. Suddenly, our color palette was doubled, brightening landscapes and adding more detail to characters than ever thought possible.

This led to a strong Console War—the collective title given to competition among game console developers—which bred innovation. This innovative era arguably reached its peak in 1996, at the onset of the 64-bit era, with a little game called Super Mario 64.

When Super Mario 64 released for the Nintendo 64 console, it completely changed the game (did you expect a pun-free article?). It showed other development teams just what the new 64-bit systems were capable of.

A small development team, Rare, took inspiration from this and built several of the Nintendo 64’s biggest 3D platformer games: Banjo Kazooie, Banjo Tooie, Donkey Kong 64, and Conker’s Bad Fur Day. These games, combined with the launch title Super Mario 64, marked the genesis of a new genre of video games, one which would encompass most future Zelda titles: The 3D Platformer.

“My favorite 3D platformer game is the one where the main character and his trusty partner who is always at his side both come from a forested area and have to do battle against their magical, green-skinned nemesis who’s taking over the world and turning it upside down! You know, the one where they travel all over the game world collecting tons of items, and then they end up doing battle in a huge tower at the end?” “Oh, you mean Ocarina of Time?” “Uhhhhhhh—”

3D Platforming had several core features that frequently played their parts in its games:

- The action of platforming: jumping from place to place, sometimes swinging on vines, sometimes flying through the air. One way or another, you were moving forwards, backwards, upwards, and downwards.

- Often, a characteristic of puzzle-solving, usually involving moving objects within the 3D space. Pushing blocks, pulling levers, activating buttons, swinging all manner of tools and items.

- The all-important adventure characteristic—the sense that you were on a journey, that you were exploring new lands. The feeling that you had a purpose in whatever world you were inhabiting, that you had the power to influence or elicit change: save the world, save your village, save the princess, overthrow the overlord of the overworld. Or maybe you just wanted to get all your bananas back.

All of these developments and innovations ultimately led Nintendo to push for a follow-up to their release of Super Mario 64: something that would be equally impressive, that would reignite faith in their first-party releases, and something that would, ideally, change the way people thought of gaming.

All of this led to the development of the game we all love and cherish, likely the game that brought you to this very article: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. And this game quickly became so much more than even Nintendo envisioned.

What makes a Zelda game a Zelda game?

At the point of our decision to push forward on writing Hero of Time as more than just a fun thought experiment, we knew that we were toying with those same 3D Platforming mechanics: the action-fueled movement, the puzzle-solving, and the difficult-to-describe “adventure” element. We turned to Ocarina of Time for a great deal of inspiration and guidance; we wanted to know precisely what made this game so fun, so enchanting, and such a great story.

Several things made Ocarina the unique storytelling game that it is. One of the things people remember most about the game are the numerous, complex dungeons that spanned the game’s world, each one filled with puzzles upon puzzles in three dimensions, each one built on a theme, and each one utilizing a major new mechanic, whether that be a boomerang, a new arrow type, or the incredibly handy hookshot.

“Wow, this is the coolest thing I’ve ever gotten from racing a creepy dead guy!”

One of the other facets that made Ocarina of Time a true development feat was the sheer size of the game, and particularly of Hyrule Field. In the original design phases, Miyamoto was designing the game based on the limits of the hardware. Due to the constraints of the memory available on the Nintendo 64 at the time, the original design of Ocarina had the entirety of the game taking place inside Ganon’s tower, with each of the “dungeons” being rooms that Link would navigate through.[5]

Thankfully, Miyamoto pushed his developers to push the hardware to its absolute maximum limit, and as a result, we were given the sprawling (and incredibly beautiful for its time) Hyrule Field as a central hub used to traverse the game’s various locations. This took what would have been a claustrophobic dungeon-crawler and transformed it into a massive explorable world full of creatures and locations that made the player feel like there would always be more to explore, and like there was an entire world of Zelda places and people out there.

Ocarina of Time really pushed 3D Platforming to its limits, including perspective-changing puzzles like this one from the Forest Temple.

After the huge critical success of this game, fans began to identify two primary aspects of Ocarina as being true characteristics of a Zelda game:

- Utilizing items acquired in each dungeon to complete that particular dungeon

- The sense of exploration and adventure that comes with journeying from place to place, uncovering new items and characters, and learning about Link’s role in Hyrule’s mythology.

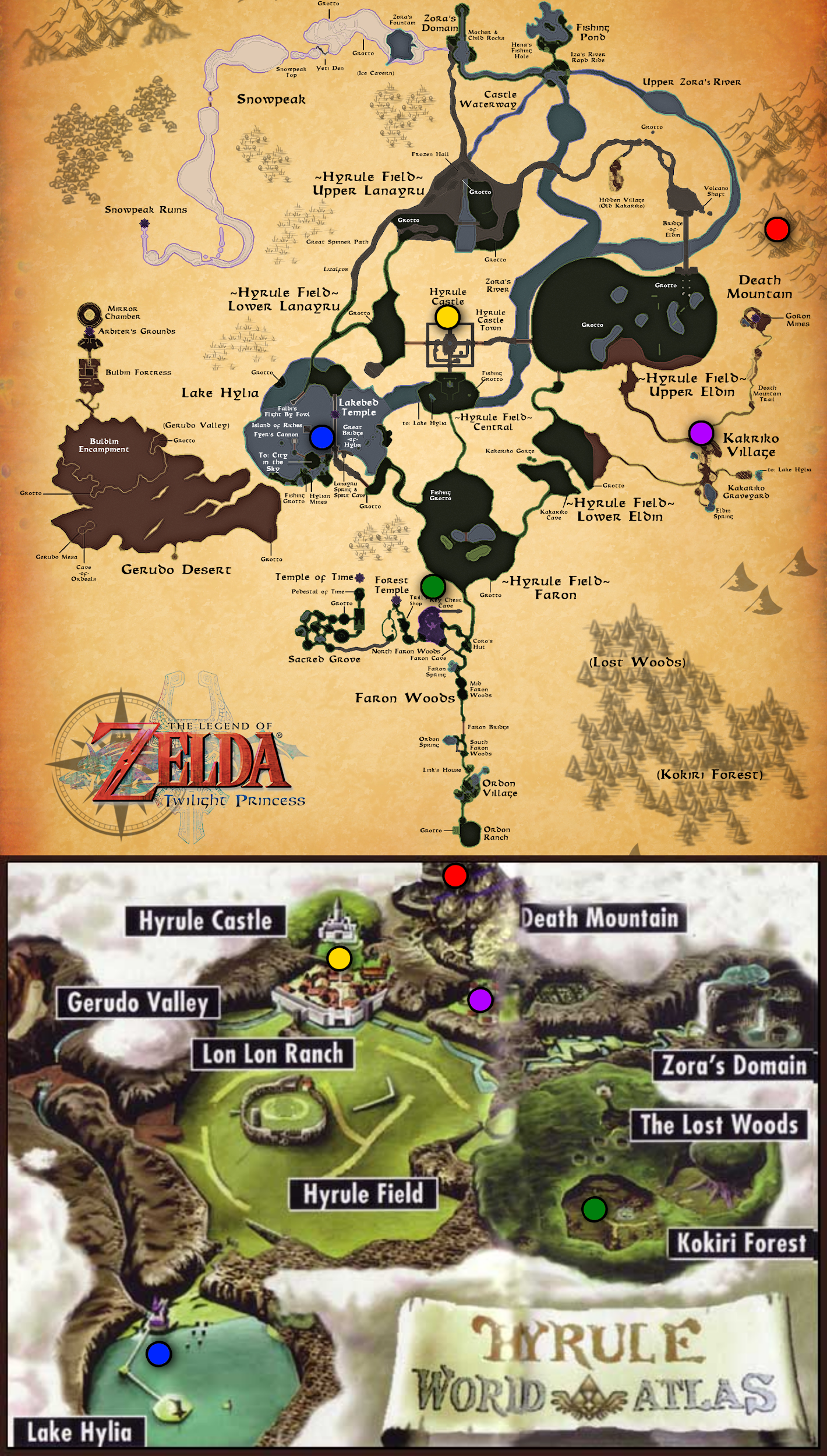

These characteristics would go on to play huge parts in the development of Majora’s Mask, which was developed with the Nintendo 64’s Expansion Pak in mind—an accessory to the Nintendo 64 that doubled the available RAM from 4MB to 8MB (still smaller than a single MP3 file by today’s standards). These characteristics were also cornerstones in the development of Twilight Princess, which saw a future version of Hyrule that was even more expansive than Ocarina thanks to the improved hardware of the Gamecube and Wii. And, of course, they went on to play a huge role in the way we wanted to write Hero of Time, both as a game and also as a story.

A comparison between Ocarina and Twilight Princess’ Hyrule overworlds. Note the similar geographic landmark layout. If one were to rotate the Ocarina map, the similar landmark locations become immediately apparent.

What makes Hero of Time a Zelda game?

When we started thinking about what a successor to these games would be, we knew that Hero of Time, though not an actual “game,” would need to have these same core gameplay characteristics: it would need to incorporate items, puzzles, and dungeon-beating, it would need to take place in a Zelda-styled world which harkened back to other Zelda locations, and it would need to convey a strong sense of adventure and exploration.

These tenets would be our primary way of making the story of this hypothetical game feel authentically Zelda. So, much like the development of Ocarina and other big-name Zelda titles, we started with the structure of the game before we began developing our story. We started taking aim at locations, characters, and items, and we wanted to re-examine Link himself. We re-tooled previous locations, re-developed some of the characters, and we had to decide how to shape our vision of Hyrule so that it felt thematically consistent with its predecessors.

Once our structure was done and once we had a good idea of some of the forms and themes that this story would utilize as its foundation, we moved on to constructing what we feel is an authentically Zelda story to go along with it.

The Temple of Time acts almost as a monumental, story-based testament to the core gameplay mechanic: time itself.

The big, core theme of Ocarina was definitely time: specifically, the comparison between old and new, and how these things can intermingle. This relationship would become our core theme as well, and it would be the primary way we told our story. So many of the Zelda games base their presence in the canon by their relationship to other games, their placement in the timeline being driven by the way major events in the series can be translated from game to game, and we wanted this story to be exactly the same. So, we had our focus. We had what we felt would be the very foundation of Hero of Time: the relationship between “old” and “new.”

Old and New

Old and New can rear their heads in many different ways when it comes to telling a story—particularly a story about time, and particularly particularly a fan-made story about time resting on the laurels of a few other stories about time that came a decade or two before it.

You have the old games and the new story contrasting with one another as a primary element: we knew that we wanted Hero of Time to be a different-but-similar story to Ocarina and Twilight Princess. We also knew that, one way or another, we were going to have to find a way to take the old and make it feel new—something the developers of Zelda titles are all-too familiar with.

A good example of doing this outside of the Zelda series is Tatooine, from Star Wars. Forgetting for a moment that the rest of The Phantom Menace is pretty… menacing… the scenes that take place on Tatooine are widely considered some of the best parts of the film (it’s like someone made a slightly better movie and sandwiched it inside a really bad movie). Tatooine was originally a setting used in both Episodes IV and VI, but is re-explored in Episode I.

Little known fact: the original title of this film was “Anakin the Menace,” and it was meant to be a science fiction parody of Hank Ketcham’s Dennis the Menace. Other little known fact: that’s not true, but it’s a better excuse for this giant flaming pile of [EDITOR HAS CLIPPED THIS CAPTION]

Reinventing a story’s setting has been the method that has made Legend of Zelda the iconic franchise it is today. Every new Zelda game has taken advantage of how much we love Hyrule by recreating it: a new engine, new puzzles, and a new story—elements that are drenched in the same tone and themes as its equivalent from the previous game, but now set in a world that we know is somehow different. One that fits thematically, but still stands as being unique in itself.

But in order to tell a story that sets itself apart as being unique, we have to introduce a different kind of old and new, which becomes especially troubling when navigating the waters of a well-loved franchise: new, original content.

In any franchise, a sequel should bring new material to the story. Games like Twilight Princess are excellent examples of both why the process benefits from reinventing old ideas, and why it also benefits the experience of the viewer to bring in completely new ideas. If a new story in a franchise isn’t doing something at least a tiny bit different, what is the point?

“You… you put earrings on a dog?” “It’s a wolf.” “Well, that’s–” “CREATIVE?!” “I mean… it’s something.”

Games often take advantage of this kind of thinking because games have very different, more practical needs when it comes to sequels. Game sequels have an expectation of expansion: not just expanding the story, but also expanding the game mechanics along the way. Usually, this involves creating new levels that take place in new settings. If the story takes the player back to an older setting, it behooves the developer to make that older setting feel as though it belongs in the newer story.

The struggle to writing new content is the how: how should it be written? The short answer is that there is no short answer to this question. Everything in writing is context-sensitive, which is why understanding the themes of the genre or series you’re writing for is important. The pitfalls of what does and doesn’t work in any particular series are many. Some ill-advised ideas can sound good on paper but be bad in practice (Like Tingle. Literally all of Tingle). This means that a lot of writing becomes an unfortunate exercise in trial and error. While introducing new settings or locations is usually an easier task, the true challenge is introducing new characters to an existing series.

Kakariko Blues

In order to illustrate the above point in practice, we’ll look at Kakariko village from both Ocarina and Twilight Princess. Remember that one of the major points of writing in new content to an old series is that “Everything must feel old and new,” and Kakariko is a solid example of what this can look like.

Micheal from Belated Media in his popular video, “WHAT IF STAR WARS EPISODE II WERE GOOD?”

In Ocarina of Time, Kakariko is virtually the only other Hylian village in Hyrule. It sits in the shadow of Death Mountain, a massive active volcano inhabited by the Gorons. It’s also near a river that leads to Zora’s Domain, another somewhat independent group of non-Hylians. Lastly, there’s a large graveyard in Kakariko, that is definitely haunted. And, unbeknownst to the residents, the simple town of Kakariko contains a dark temple underneath this graveyard. Kakariko is meant to feel like the edge of human civilization, the border between the Hylians of Castle Town and the non-Hylians that inhabit the other parts of the world.

Contrast Kakariko against Castle Town, which, after Link visits the castle itself, only truly serves as a place to resupply. There’s no danger in Castle Town—er, when Link is young—because this is where the people live. The world of Castle Town is commerce, communal living, and a generally joyous atmosphere. But Link is a hero; he doesn’t belong in a place with no danger. So you buy your stuff, play some minigames, chase down the dogs, and move on.

(There weren’t any good gifs of the dogs in Ocarina of Time, so have this gif of an over-excited dog from Twilight Princess instead.)

In Twilight Princess, Kakariko returns, largely the same as it was before. Kakariko is still the edge of civilization in the area it inhabits. It’s also still surrounded by danger, including when you first walk into town and a group of Moblins and Bokoblins have taken over. However, the developers of Twilight Princess also added some new ideas into the mix. Kakariko is further away from Castle Town and the Lost Woods now, which is largely because the map of Hyrule is bigger in Twilight Princess, so the distance naturally scales up. The developers also supplemented the ‘edge of civilization’ theme by adding a wild-west theme to really hammer in the hardy, weathered survivalist feeling the town and its people should give off. Many of the Hylians appear in a quasi-western style, and a few of the town’s residents even appear as a kind of native people, strangely similar to Native American tribes such as the Hopi or the Shoshone.

There are only two things this here Cowboy loves more than life itself: the wild, wild west, and Señor Whiskers.

Again, one of the purposes of changes like these is to allow the viewer to ground themselves in something familiar, while still doing something new and different. If it wasn’t grounded in familiarity, it wouldn’t be Legend of Zelda, Star Wars, Halo, or whatever it’s actually supposed to be. At the same time it should feel new, that sense of newness creates a hunger and a motivation to see the story continue, or to explore, or to reach the next highest level—something that can ring true even if you’re fairly new to the series.

As a side note, none of this is to say that entirely new content is to be feared and shunned. But new content should still be carefully processed so that it feels naturally integrated with the older content. In short, whatever the new content is, it should make sense in the context of the established world, history, and themes.

A good example of this in Zelda is the addition of the Peak Province and Snowpeak Ruins in Twilight Princess. The Legend of Zelda had done snowy levels before, but Ocarina of Time did not have a snow region attached to its version of Hyrule; therefore, its inclusion in Twilight Princess was entirely new. Not many people really cared or spoke up about that change to the series; after all, adventure games had been taking players to a large variety of biomes for decades, and it only made sense from a gameplay perspective. Along with that, the new region was built with a tone and story in mind that was very naturally fitting to the game and the series at large.

Our Return to Hyrule

With a better understanding of both how stories are written, and how sequels are written, we can move on to understanding our own fan-made entry into the series by introducing you to some of the changes we’ve made. We hope that our changes, by adhering to the thematic guidelines we’ve set up, will illustrate what these themes and ideas look like in practice.

For a while now, we’ve alluded in very vague terms to the plot of Hero of Time. It’s not our intention to hold that over your heads as an audience as though we’ve found the holy grail itself—and you’re not getting any, muhahahahahaha. The truth is, we wanted a chance to explain our thought process, and to give you a glimpse into part of the journey we took several years ago when we first wrote down this story.

In the future, our plan is to actually present the story chapter by chapter, so that it can be displayed and finally enjoyed here on WaTF. Until then, what follows is a few pieces of the world we created, and of the story of Link’s last days.

In our story, Hero of Time, we wanted to create a Hyrule that was a little different from its many other iterations. In this story, we’re getting a chance to revisit a Hyrule that hasn’t been waiting hundreds of years for Link’s return—it has only been waiting a few decades. As we mentioned before, this new look at Hyrule would be a balancing act of old and new. For us, it meant adding new towns and locations in the story, but still allowing the plot to center on the familiar locations of Ocarina of Time.

In Hero of Time, some of our original content is based on some assumptions. The first of these is that the Child Era timeline sees a Hyrule that prospers in the wake of Ganon’s defeat. We’ve chosen to allow that prosperity to appear in the form of economic boom, and settlement expansion. Lon Lon Ranch would have been a convenient location for traders who wanted to do business in Castle Town, but couldn’t necessarily afford to stay there. This increase in visiting traders and eventually settling farmers leads to the creation of Lon Lon Town.

The ever-bustling Lon Lon Ranch. Population: 3 Hylians, 2 cows, Epona, 6-7 other horses, and some chickens.

We wanted Lon Lon Town to be a fairly central location to the plot because it’s a new town, but one that rests on an older story—namely, Link’s friendship with Malon in the past. Lon Lon Town also comes with the immediate mystery of, “Where is this town in Twilight Princess?” So, Link can spend a lot of time here, reconnecting with old friends, partying, shopping, and essentially building the beginnings of a proper home in Hyrule (somewhere that is homely, but isn’t quite the city of Castle Town). But these feelings of goodness and familiarity come with the foreboding idea that this town will have to somehow disappear in the next 30 years before Twilight Princess, since it’s absent from that game.

Of course, while making connections back to Ocarina of Time is all well and good, that wasn’t the only direction we could go. Another context-sensitive pitfall is the appearance of practically worshipping Ocarina of Time. If too much emphasis is placed on Ocarina of Time, focus might be lost on other connections to Twilight Princess, as well as compromising the story’s more original content. You always want to show the story love, but you should also strive to create a story that stands on its feet: something old, but new. For that reason, among others, we also wanted to include connections to Twilight Princess, including a recently settled version of Ordon; this helps to connect the story to Twilight Princess, being only about 115 years after Ocarina of Time, and therefore about 30-40 years after Hero of Time.

Changing the Legacy

Among the most exciting aspects of writing a new chapter of an old story is the creation of new characters. In the beginning of writing Hero of Time, the biggest pitfall we identified was our own resistance to change in Legend of Zelda, an issue we knew we shared with other fans of the series. The most potentially controversial decision was to include the creation of a royal family.

The decision to write these characters in is probably one of the strangest and riskiest choices, for a number of reasons.

- Taking a well loved character and introducing a family member is always risky because it can either appear as self insertion (depending on whether that character is the main character), or simply that those kinds of characters depend too heavily on the presence of the main character to be relevant to the plot.

- Additionally, giving Zelda children has never really been done before, and opens a whole new can of worms. Now we’ve introduced intimacy into the series in a way it hasn’t been seen—and a lot of questions can be raised over things like Zelda’s unprecedented marriage, and who she’s married to (because, spoilers: it’s not Link).

But our choice to create a royal family does flow from a line of logic based on the series itself, and from real medieval history.

A commonly known fact of medieval life was that power, politics, and family went hand-in-hand. Princesses and princes were commonly married into the royal families of other nations in order to secure an alliance, often opening the door for those two nations to become one over time. Alternatively, one could marry into a noble house inside the country, fostering loyalty between a royal family and their noble vassals; however, this was typically in either politically isolated countries, or it was the fate of 2nd and 3rd children in the family.[6] It was extremely important for a marriage of any kind to have political importance, and it would not be until the renaissance that women ever ruled by themselves (See Elizabeth I,[7] Catherine The Great,[8] Christina of Sweden[9]).

Christina, Queen of Sweden. Ruled Sweden from 1632 to 1654.

However, the world of Zelda is a fantasy world; therefore, history informs the writing, but does not dominate it. Firstly, in order for the Hylian royal family to marry anyone, there must be either nobles who control the various regions of Hyrule, or there must be other kingdoms in the world Hyrule inhabits.

There is evidence that other Hylian/human kingdoms might exist; hints gathered from older sources such as the Legend of Zelda cartoon that featured a prince from a nearby kingdom, or from games like Majora’s Mask that takes place in an entire other realm, albeit one that exists in another reality. Legend of Zelda’s history with other kingdoms tends to be that those kingdoms usually belong to other races: the Zora have their own king; The Realm of Twilight from Twilight Princess also had its own royalty; and the Gerudo supposedly gain a king every hundred years or so. What these various themes add up to is not a canonical confirmation of other human/Hylian kingdoms, but rather a thematic precedent to reintroduce the concept as a useful background theme.

Simply put, there are other kingdoms, and in the years since Ganon’s fall, Hyrule now has to deal with them again.

Look at that MAGNIFICENT mullet.

From here, the story of Zelda’s family is fairly straightforward: we know that if there is a Zelda in Twilight Princess, then the Zelda of Ocarina of Time had some sort of family. Her family in our story is the result of a political marriage to a prince from an unnamed neighboring kingdom. Of the two, Zelda is the more powerful monarch, and when her father passes on, she becomes the primary ruler of Hyrule, Queen Zelda, with her husband as King.

Although, with the extended number of years following Ocarina of Time, men do live shorter lives, particularly in medieval times when men were commonly relegated to the jobs of hunting and warfare. Eventually, Zelda’s husband dies (whether of natural causes or violence remains unknown). Zelda continues to rule as Queen, but as her two children grow older, they also begin to assist in rulership of the kingdom.

In Hero of Time, Zelda’s two children are Princess Marigold and Prince Robert. Without giving specific ages, Marigold is the eldest, and has a child of her own: Princess Zelda II. Like her mother, Marigold is a widow, and next in line to the throne should Queen Zelda pass away. Marigold is like Zelda in many ways: she’s wise, patient, cheerful, and suited to her status as princess.

Prince Robert, by contrast, is the image of his father. Robert is a little more militaristic, serious, and deeply protective of his family. His role at court is to act as General for the army, and as a result, he is constantly thinking about the dangers that threaten Hyrule.

Our hope is that with these small additions in the legacy of Zelda, we can begin to tell a truly different and interesting story without sacrificing the themes and conventions that made Legend of Zelda the great story that it is today.

While that’s all we’re going to reveal in this installment, we hope these characters help you better understand how we approached creating new, original content, and we hope it builds your anticipation to hear Hero of Time in full as we begin the second half of this series: a narrative of the plot of Hero of Time, with selective analysis highlighting some of the notable elements of the story.

Where We’ve Been and What Lies Ahead

Throughout the many articles we’ve written so far, we’ve tried to establish the many important themes and facets of Hero of Time: themes such as the importance of player/character connection, the possibility of growing the series up to match older fans, and the importance of creating narrative and canonical coherence.

In the future—the future being the very next article we publish—we’re going to begin telling the story of Hero of Time in earnest, one chapter at a time. That isn’t to say that the analytical work we’ve begun will stop, of course. We’ll continue to address important themes, dramatic highlights, and other purposefully made character and setting choices; but we’ll do so alongside our narrative so that you, the reader, can see these ideas in practice (and so that we, the writers, can finally tell a story very close to our hearts).

We look forward to seeing you next time, as we begin the second phase the Hero of Time Project.

Jaron and CJ will be discussing this article series in “Can Fan Fiction Teach Us About the Official Zelda Timeline?”, one of three panels With a Terrible Fate is offering at PAX East 2018. Don’t miss this chance to learn more about the series and join us in a conversation about Zelda and fan fiction!

Endnotes

- Source: http://www.vgchartz.com ↑

- http://www.maddamart.com/blog/?page_id=2 ↑

- An idealized and seemingly perfect fictional character. Often, this character is recognized as an author insert or wish fulfillment. They can usually perform better at tasks than should be possible given the amount of training or experience. In some contexts the name is reserved only for women, but more often the name is used for both genders. A male can also be referred to as a Marty Stu or Gary Stu, but Mary Sue is used more commonly. Source ↑

- Original Content (OC), in the context of fan fiction, often refers to content that does not outright exist in the source material, but is added as a means of telling the fan-fiction story. An (awful) example of this would be Cold Steel the Hedgehog. ↑

- “Iwata Asks” http://iwataasks.nintendo.com/interviews/#/3ds/zelda-ocarina-of-time/4/0 (Note: this is an example of the above-mentioned non-canon information that we still take into consideration. It’s not a part of the canon of the series, but it definitely played a part in our design for HoT.) ↑

- European Feudalism: Mcdougall, Sara. “The Making of Marriage in Medieval France.” Journal of Family History, Vol.38(2), 2013, pp 103-121 ↑

- Queen Elizabeth I of England ↑

- Catherine the Great of Russia ↑

- Queen Christina of Sweden ↑

1 Comment

Greg Kramer · November 3, 2019 at 2:49 am

First, i loved the article.

There is a simple answer to “what makes a Zelda game a Zelda game…”

The person who plays the game and experiences the wonder and excitement…they know what the game is. A proper Zelda game gives that to the player. There are gamers who won’t get it, but they usually love FPS. This is different. A proper Zelda game makes you come back. There is no exact mechanic for it. There is no dungeon that explains it. It is that sense that you are embarking on something so new, yet familiar(at least since ALTTP), that you allow yourself to fully immerse. And even better, if you are new to it all…you are able to experience it the first time. This has been built over time (pun intended) and couldn’t be what it is, if for not the bigger picture.

Long live the Zelda franchise. I have been able to play them with my own children now. They have the same twinkle in their eyes…this is unique and special. That is what makes a Zelda game a Zelda game. The enthusiasm of my 4 yr old can attest to that.