The following is part of Now Loading, a series that renders verdicts on whether or not your favorite video games deserve a place in the canon of works that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. Read the series’ full mission statement here.

Running Verdict Simulator

>>>NOW LOADING...THE VIDEO GAME CANON

>>run ladiesandgentlemen.exe

>>VERDICT RENDER

>>PORTAL

>>LOAD MODULES [INTRODUCTION] + [STORY AND CHARACTERS] + [GAMEPLAY, VISUALS, AND MUSIC] + [IMPACT ON GAMING AND CULTURE] + [VERDICT]

VERDICT ERROR

VERDICT ERROR

>>CONFLICTING VERDICTS

>>run verdictsimulator.exe

>> VERDICT SIMULATION 0001

Well folks, I think this verdict is pretty cut and dry. I mean, look, we all love Portal and all the many memes it’s given us over the years, but when we look at it as more than the sum of its parts, it really doesn’t offer us much more than a well-constructed puzzle game with an interesting villain. Without GLaDOS, this game is a pretty bog-standard project picked out of obscurity by Valve. Although, when it comes to GLaDOS

>>VERDICT INCONCLUSIVE

>>VERDICT SIMULATION 0023

When looking at Portal subjectively, it’s easy to be taken in by its many charms. However, if we put on our trusty OBJECTIVE CAPS, we can see that Portal is really just a tight, well-constructed, B-grade puzzle game elevated to a solid B+ thanks to a compelling antagonist. GLaDOS is many things, but perhaps most importantly she is the driving force moving the player forward in her quest through Aperture Laboratories, and without her constant verbal prodding, the game almost feels like a tutorial, constantly teaching you how to use a mechanic without ever ramping up to a real story

>>VERDICT SIMULATION 0167

Okay, sure, Portal is a one-trick pony dangling the fun antagonist in front of the player like a proverbial carrot, but isn’t the fact that that one trick—i.e. the flawless game mechanic after which the game is named is so fun and tightly designed—reason enough to consider this game a triumph? A huge success?

>>VERDICT SIMULATION 2297

The game is just the portals and puzzles but it needed an antagonist so it didn’t feel like a long tutorial for a different game so they put in GLaDOS to make fun of you and push you onward but to hear her quips and laugh you need to progress so you learn the mechanics so you hear the quips so you play the game but what is the point what is the point

>>VERDICT SIMULATOR 4992

what is the game saying what is the theme of the game is it just a fun game can i even have fun anymore is there more is there is there is there more

>>VERDICT SIMULATOR 7681

Sure, between the tight game mechanics and the hilariously well-written antagonist GLaDOS, Portal has a lot to offer the player in terms of pure entertainment. But when it comes to presenting us with an interesting narrative, there’s a pretty shallow well from which to plumb. And besides, I’m not sure any of us really has the correct tools

>>VERDICT SIMULATOR 8309

What do we talk about when we talk about Portal? Sure, we talk about the cake being a lie, we talk about GLaDOS and how brilliantly her character is used in the game as an antagonizing force that propels the player forward throughout the labyrinth of puzzles and traps, and we talk about how satisfying it is to use nothing but our skill, wit, and the tools provided to us in the game to get to that catchy end-credits song. What we don’t talk about, however, is the interesting meta-commentary on video games and their design and production that the whole setup of Portal reflects. The game, at its core, is the story of a lone person being given a tool by an antagonist. That antagonist then teaches the lone person how to use the tool so well that the whole thing ultimately results in the lone person using that tool to dismantle the antagonist who taught them how to use it in the first place. In this way, it’s as if

>>VERDICT SIMULATOR 9109

cake is so goddamn hilarious

>>VERDICT SIMULATOR 9998

Is Portal the prelapsarian ideal of what a game is?

VERDICT ERROR

INCONCLUSIVE DATA

COLLABORATION RECOMMENDED

>>LOADING PAX SOUTH 2018 PANEL DISCUSSION

Dear Reader, allow me, if you will, to be real with you for a moment. Writing these articles isn’t always easy, and while I will typically go into one of these discussions already having a sense of whether or not the game in question belongs in the Video Game Canon, there’s always the odd game that comes along that has me wishing and washing all over the place. And as you can see from my verdict simulation program I shared with you above, I often waffle back and forth on a decision hundreds, if not thousands, of times before finally coming to my conclusion and presenting you all with my argument for whether or not a game should be inducted into the Canon. And the latest game in this list of undecideds is, I’m sorry to say, the fan-loved and critical darling, Portal.

I know, I know: I can practically hear the keys on your keyboard flying off and hitting the wall as you reign down your furious wrath upon me.

“HOW DARE YOU, SIR,” you begin politely, “EVEN BEGIN TO INTIMATE THAT THE FUN, HILARIOUS, FIRST-PERSON PUZZLE SHOOTER (WHICH HAPPENS TO ALSO BE A PIONEER IN THAT GENRE, BY THE WAY) THAT BROUGHT US SUCH INTERNET CORNERSTONES AS ‘THE CAKE IS A LIE’ AND ‘STILL ALIVE’ SHOULD NOT BE AN INSTANT ADDITION TO THE CANON?”

And you know what? I’m with you! I think that Portal is an incredibly well-constructed and—at times—brilliantly written game that has clearly had a huge impact on not only Internet culture but also gaming culture writ large.

All the same, there are still these little niggling doubts that persist in my mind when I come to the verdict on this game. It’s a good game, but is it a great game? Does it deserve to be remembered for all time due to its storytelling, design, and impact on the world?

Well, I can tell you, Dear Reader, that while I was sat alone in my darkened hovel thinking these things over, I just couldn’t bring myself to lean towards the affirmative. However, like I said, those doubts still persisted in my mind, so I packed up my loose collection of belongings, bought a plane ticket with my good buddy Aaron, and journeyed to San Antonio, Texas to ask the beautiful people at PAX South what they thought.

Dear Reader, I was not disappointed.

After our panel discussing Now Loading… The Video Game Canon! and the nature of canons more broadly, we asked the con-goers to collaborate with us on the very piece you’re now reading. The crowd’s answers, insights, and points only served to reaffirm for me that Now Loading is meant to be collaborative and communal, and that the only way any of us can truly understand the brilliance (or lack thereof) of a game is to hear various different perspectives and participate in argumentative discussion.

So, as you continue in your reading, know that many of these points were culled from our discussion with the PAX South 2018 audience. This article is brought to you as much by them as it is by me.

But enough waxing and waning, let’s talk about the game!

Portal, like many games that came before and after it, has a development history almost more interesting than the game itself. Way back in the distant past (2005), a small group of students headed by Kim Swift and Jeep Barnett at DigiPen Institute of Technology released their senior project game, Narbacular Drop, for free online. The game was a very clear precursor to what would eventually become Portal, boasting similar game mechanics and sporting a story about a girl trapped in a dungeon whose only means of escape was to solve puzzle after mind-bending puzzle.

Well, good ol’ Gabe Newell and the team over at Valve smelled what Narbacular Drop was cooking and wanted a piece of it. So, shortly after the release of their senior project, Swift, Barnett, and the rest of the Narbacular crew were taken in and put to work on Portal.

The interesting history doesn’t end there, however, as anyone tangentially familiar with Valve’s idiosyncrasies could guess. Though Newell and the rest of the Valve bigwigs were just as interested in Portal as they were in any other game they were developing, designers and producers alike worried that the game might be seen as “that weird puzzle game Valve tried that one time,” and they didn’t want to feel like they were giving the game any less than it was due.

Because of this, they decided that the game would be packaged in a collection called The Orange Box alongside Half-Life 2 and its episodic sequels, along with a little-known venture called Team Fortress 2. They were under the impression that Portal and Team Fortress 2 might gain some traction if they had a paired release with the cultural juggernaut that was Half-Life 2.

Little did they know that the little-puzzle-game-that-could would turn out to be the sleeper hit of the collection.

Well, Dear Reader, I think you and I both have had enough preamble at this point. Without further ado, let’s take a look at the real meat of this game and put my waffling to an end. Let’s decide whether or not Portal belongs in the Video Game Canon!

Story and Characters: Are You Still There?

The literal story of Portal is one of the more straightforward ones that we have discussed in this series. Despite a few examples of an “inferred lore” (the Rat Man who hides in the testing facility’s walls, Aperture Science’s connection to Black Mesa and the events of the Half-Life series happening concurrent to Portal’s story, etc) there isn’t all that much to flesh out the story.

“I’m afraid that it’s time for some tests, Dave.”

You play as Chell, a silent protagonist who wakes up to find herself trapped in a pristine glass cell with only a radio as her companion. She is woken up by a disembodied robotic voice who tells her that “the tests” are about to begin, and would she kindly step through the portal and into the testing chambers.

Once the portals have been introduced as a concept to the player, she is shortly able to get her hands on the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device, or “portal gun” as it has become known, so that she can participate more fully in the tests and proceed through the examination chambers.

“Its safety is unprecedented!” —Deceased Former Test Subject

What follows is a sequence of rooms in which the player uses the portal gun to open two holes in space through which the player can travel at will, place boxes on buttons, redirect lasers to activate buttons, manipulate momentum to leap over huge pits of gross death liquid, and generally make her way through the Aperture Science testing facility. All the while, GLaDOS, the aforementioned disembodied robotic voice, mocks and humiliates your intelligence and ability, dangling promises of baked goods as a reward if you can find it in your feeble little head to pass all the tests.

When you finally make it to the end of the last “test,” GLaDOS informs you that you have successfully completed the gauntlet of challenges (good for you), and that you are done for the day. After a modest moment of congratulations, she puts you on a conveyor belt leading to your doom at the bottom of a fiery pit. Luckily for you, you still have the space-hopping device attached to your arm, and you’re able to escape into the bowels of Aperture Science.

As you travel through the maintenance tunnels and back rooms of the laboratory, you slowly come to realize that the only real way out of the complex is to destroy the A.I. who has been simultaneously mocking you and driving you forward in your quest. After ducking under pipes, running through tunnels, and using the portal gun to great effect, you eventually make it to GLaDOS’ operating room and dismantle her piece by manic piece until the entire complex blows up, freeing you from the manic tester’s grasp. At least, for now….

Ah, the sweet release of… Semi-urban Industrial Complexes.

As it is, the story is fairly lackluster and amounts to a person overcoming a tormentor. While that’s a tried and true story trope, Portal unfortunately doesn’t build much around it, and so it ultimately becomes the story of a prisoner escaping a prison. It’s compelling and has some exciting moments, but it’s hardly offering anything new to a tried-and-true favorite story.

Where the game shines is not in the retelling of a basic narrative, but rather in the relationship between the player and the antagonist, GLaDOS.

GLaD to meet you.

GLaDOS is that rare mix of charming, sardonic, sadistic, and evil that only the best villains have achieved. Without her constant poking and prodding of the player’s intelligence and ability, Portal would be little more than a prolonged tutorial explaining a particular game mechanic to be used in a much larger game. It is through her constant antagonism that the player actually feels enticed and driven to navigate her way through the various perils of Aperture Labs. What’s more, in giving the character the tools to progress (i.e. the portal gun and the circumstances in which to learn its functions), she is effectively the architect of her own demise.

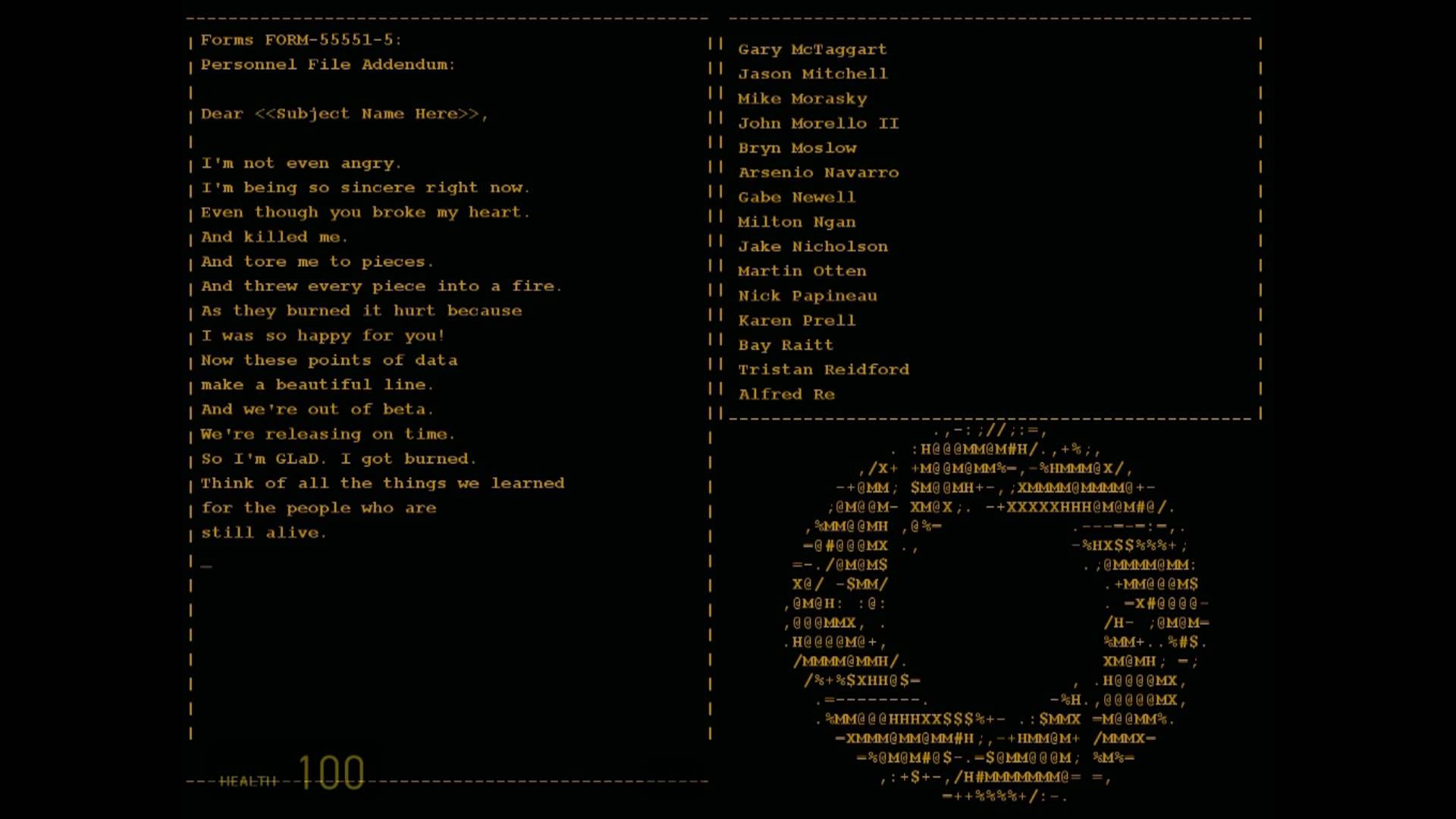

And yet, if we look at the lyrics of the end credits song, “Still Alive,” we realize that not only did we fail in our self-appointed objective (killing GLaDOS,) but that she actually sees the whole experience as a “huge success.” GLaDOS marks Chell’s run through the laboratories as a “triumph” because the ultimate “test” was teaching a person how to effectively use the portal gun. Sure, GLaDOS was attacked at the end of the game, but she was attacked using all the various things that Chell learned as she made her way through the labs with the gun; so, as far as GLaDOS is concerned, she won. She did her job, and ran a successful test of the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device.

Joke’s on you, nerd.

This idea that the whole game was itself a test speaks to the meta-narrative genius of not only the character GLaDOS, but also the game Portal as a whole. If we think of GLaDOS as a game designer, (and, in the world of the game, that’s what she literally is), the tests in Aperture Laboratories as her various different games, and Chell as the player engaging in said games, Portal becomes an analysis of how a game creator interacts with a player as the game is taking place. If we wanted to be really abstract, we could even argue that the whole of Portal is just Valve testing whether or not the concept of a game in which there is only one mechanic can hold a player’s interest for a number of hours.

The answer, it turns out, is “yes,” but only if you have the presence of an antagonistic creator pushing you along. GLaDOS, like Valve, recognizes that the only ingredient one really needs to run a successful test is a little bit of sarcastic negging. The difference between a game mechanic and a game is the drive to move forward, after all. I’m making a note here, Valve.

Huge success.

I CANNOT STOP LAUGHING AT THIS CAKE

Gameplay, Music, and Visuals: So Sleek, So Fine

I have already referred to the portal-making mechanic in the sections above, so I won’t belabor the gameplay point here any more than I need to. I will simply reiterate that Portal is centered on a very fun, very well-explored and well-explained system of shooting one portal on one surface and then another onto a different surface, and manipulating physics and momentum in order to solve a number of different types of puzzles.

As far as gameplay goes, I would be hard-pressed to find a game that explores a mechanic more fully or more deftly. And to clarify, when I say that there is only one mechanic in this game, I am not saying that there is only one thing that the player is able to do. The player is able to do a whole host of things with the portal gun, but the fact of the matter is that the portal gun is the one and only tool at the player’s disposal, and the game exhausts that one mechanic over the course of the game. Granted, it exhausts it brilliantly by teaching the player everything she needs to know about the portal gun, and then having her utilize those lessons as she progresses throughout the testing facility. In that way, Portal is the perfect example of a game wringing every ounce of potential out of its design concept.

As for the music, Portal’s soundtrack is comprised of a number of ambient, science-fictiony sounds, as well as ambient background music that sets the tone but does not necessarily stick in one’s ear. With the notable exception of “Still Alive,” the sardonically victorious song sung by GLaDOS over the end credits, most of the music is relegated to background noise and mood setting. Certainly not horrible, but not necessarily a game-changer in the world of video-game music.

To get a sense of the visuals, I would like you to participate in something of a thought experiment with me. Imagine if you will, Dear Reader, an alternate history in which Steve Jobs was more of an outwardly evil lunatic genius, and yet still had the sort of retro-future, all-white, sleek aesthetic when it came to design. Now, imagine that instead of Apple, he created a weird think-tank company, named it after part of a camera lens, and decided to funnel all his funding into warping space between two points with a projectile weapon instead of making a computer for the everyman.

If you aren’t picturing the testing facility at Aperture Laboratories, then my illustrative powers have failed me.

The white tiled floors and sleekly-designed testing facilities are perfect reflections of the cold, unfeeling world of Aperture and GLaDOS, and as you wend your way through the different chambers listening to your robotic nemesis insult you, you begin to realize that Aperture is a vision of the future trapped in the past. Though it may have been at the forefront at one point in time, years of cold and calculated rule under GLaDOS has turned it into nothing more than a stark white prison, slowly coming apart at the seams as the years go on and there is less and less real human input at the labs.

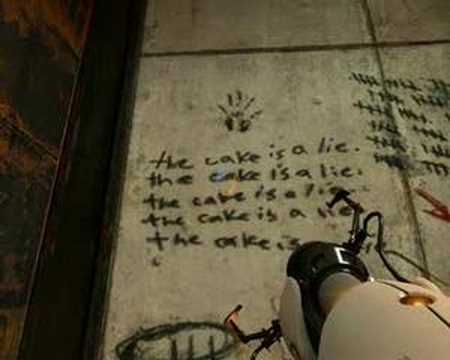

Then, as you move past the facade that only testers are meant to see, you realize that the rest of the complex is falling apart at the seams, unable to hold onto whatever vision there may have been all those years ago. It’s still cold, but the professional, white tile turns to concrete and rebar, and the scribbled writing on the walls shows that the prison you are trapped in is crumbling just as much as the minds of those who trapped you there in the first place.

Nothing like two colors in a color palette to make you slip into corporate madness.

So, while the music may not be spectacular, the bleak, deteriorated, and ultimately decrepit world of Aperture Laboratories, combined with the flawlessly executed portal gun gameplay mechanic, makes for an interactive experience that stays with the player long after GLaDOS breathes her last.

Impact on Video Gaming and Culture: I’ve Heard I Shouldn’t Trust Them Cakes, Bro

I would not be doing my due diligence as an Internet denizen without at least mentioning the memification of nearly every aspect of this game, so I will do so here very quickly and then move on to the juicier bits.

Portal had a lot of things going for it, not least of which that it was arguably the first of its kind. There wasn’t much of a first-person puzzle shooter before it, least of which one that was so tightly designed with such a distinctly witty sense of humor. Because of this, things like “Still Alive” and the infamous “The cake is a lie” (a hidden message denoting that GLaDOS’ intentions weren’t quite what they seemed) spread widely across the Internet as game culture in-jokes to the point where, if anyone mentioned the infamous baked goods line, it indicated that they were at least tangentially familiar with the game it came from and gaming culture more broadly.

“Thanks for playing, lab-rat scum!”

The memes and in-jokes were so ubiquitous, in fact, that it elevated the most unknown title on a collection of Valve games to one of the most recognizable video game titles of all time. It must be said that the power of memetic jokes and their dissemination on the Internet cannot be underestimated when it comes to popularizing a game.

Now then, with memes out of the way, let’s talk about The Orange Box and its powerful legacy.

PLEASE, THE JOKES, I CANNOT HANDLE THESE JOKES

Up until the release of The Orange Box, if a game were stuck on a collection of other games, it usually meant that it was a presumed flop fated to exist solely as a demo in one of the lesser-read issues of PlayStation Magazine. In fact, this stigma against game collections worried a number of Valve designers and producers to the point that they were fully prepared for Portal to be the black sheep of their bibliography and never be thought of by developers or players after its initial release.

However, because the other games on The Orange Box happened to be a number of entries in what is widely considered the best and most innovative first-person shooter series, players and critics were much more willing to give Portal the chance that it deserved. This not only led to Portal’s success, but also paved the road for a great many smaller independent games that might never have gotten their moment in the spotlight otherwise.

In fact, it could be argued that the success of The Orange Box, specifically that of Portal, precipitated the incredible success of another Valve venture known as Steam. Steam, the platform on which most of us buy and play our games, is a veritable breeding ground for smaller, independent video games that deserve just as much attention as their AAA counterparts. And, by being placed in similar categories with similar search results as those AAA games, smaller games bubble to the top of the list and get that very attention they need to thrive.

In that way, the Steam charts and recommended lists do for small games today what The Orange Box did for Portal all those years ago: they give great games a much-needed platform.

Needless to say, between the memes, its own merits, and its impact on the way in which smaller, independently-developed games were perceived by the general public, Portal had an important and largely positive impact on video games and gaming culture, the effects of which will be visible for years and years to come.

However, before we move on, I would like to mention one more nebulous point of influence that Portal and its sequel Portal 2 have had on how we think about video-game storytelling. One thing that I learned above anything else at our panel discussion at PAX South 2018 was that when people hear “Portal,” what they conjure in their mind is a conflation of both the original game and its sequel. I like to think that this is because the second game is so good (and in some ways better than the original) that it retroactively skews people’s memory and analysis of the first game.

It’s almost as if we see Portal as a blue portal and Portal 2 as an orange portal: two logically inseparable halves of a single journey.

Valve is no stranger to episodic storytelling, as we see with Half-Life and its serialized sequels, and so it’s no wonder that both Portal and Portal 2 are often seen as two separate episodes in the show that is “Portal.” I don’t want to dwell on this point too heavily here, as I will certainly be discussing it when I inevitably consider Portal 2 for admission into the Canon, but this episodic view of video-game stories has some interesting implications regarding whether or not we should look at whole series when we think about inducting games into the canon.

Again, I will not belabor this point in this article because it is ultimately about the first Portal, but as I end this section I invite you to contemplate what you really think about when you think about “Portal.” I think you’ll find the answer is more complicated than you initially think, and I hope you’ll join me in the future when we delve more deeply into this question.

Next time, baby.

BONUS LEVEL: Cry, Bloody Companion!

Dear Reader, I know that you are keen-minded, and so I should think you have noticed that I have, up to this point, completely neglected to talk about the weighted companion cube.

Well, I should hope that you know I wouldn’t leave our hefty-hearted buddy out of the conversation, especially because it was a brilliant way for the designers to both teach the player an important component of the final boss fight and demonstrate how easy it is for humans to attach themselves to anything that seems remotely friendly.

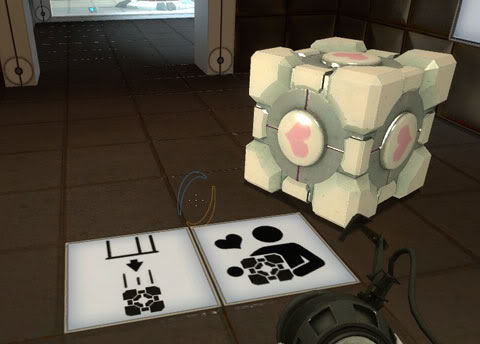

Towards the end of the game, once the player reaches Test Chamber 17, GLaDOS informs the player that, in order to get to the end of this particular test, she will need to carry the weighted companion cube throughout the entire room. It functions just like any number of boxes that you’ve encountered in your quest through the testing facility, but it is decorated with pink hearts on each of its sides, and GLaDOS tells you that it is perhaps the most loyal thing that you will encounter in the Aperture’s putrid bowels.

Though you are only with the cube for a short time, you do develop a personal relationship with it. First, it is the only thing you have seen in the bleak, white wasteland of the facility that has any semblance of warmth to it. Then, when you are told specifically by the antagonizing voice that has been constantly prodding you the whole time, that this thing implicitly loves you? Fuggeddaboutit, that thing is family from that moment onward.

Instructions AND recommendations!

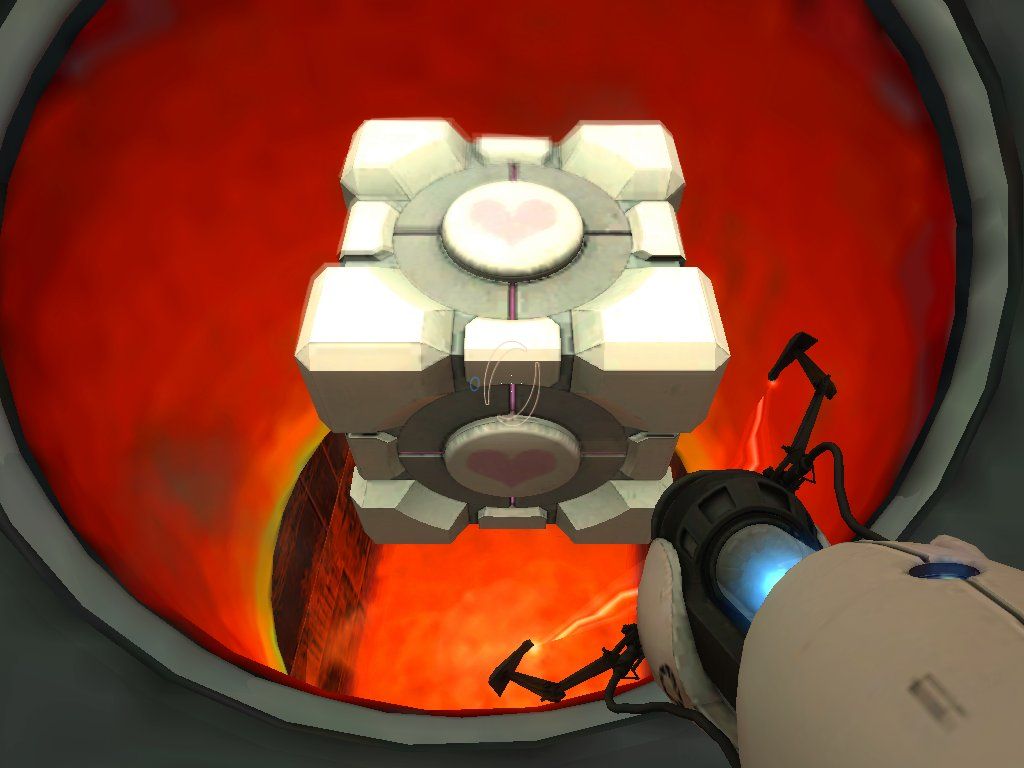

In doing this, GLaDOS (and Valve, meta-narratively) is dangling a piece of comfort and happiness in front of you—only to violently, heartbreakingly take it away from you when she tells you that, unfortunately, you cannot take the companion cube with you past Test Chamber 17. What’s more, you cannot simply leave your new friend behind: you must open an incinerator and burn it to a crisp. You must take the one thing that you have been powerfully conditioned to unconditionally love, and forcefully cremate it.

But here’s the thing, Dear Reader: you sure as hell remember that companion cube. You remember everything about it. You remember its shape, its hearts, and, most importantly, you remember the method of its demise.

“Et tu, Chell?”

Now, cut to the final boss fight with GLaDOS. Piece-by-piece you dismantle her, knocking her various personality cores off her main body. You grab them—but, what to do with them? Well, wouldn’t you know it, there’s an incinerator in the corner of the room, and what do you know, the personality cores are roughly the same heft and size as the companion cube, and what’s this, GLaDOS, the character whose whole goal it has been to see you complete her many tests and prove that the portal gun and its use can be adequately taught in any situation, reminds you of the companion cube and what you did to it.

GLaDOS, and Valve, have expertly crafted every single moment of the test to teach you how to beat it. By showing you that Aperture Laboratories technologies can be brutally, callously incinerated, they’ve ensured that you know how to destroy GLaDOS and successfully complete the test.

“What have I become? My sweetest cube?”

Have some cake.

VERDICT: Thank you, PAX South 2018

>>VERDICT SIMULATOR 9999

It’s been a long ride getting here, folks, but I think it’s fairly obvious that through our discussion with the beautiful people at PAX South 2018, I was able to see a game I was largely unsure about in a new light, and realize just how important Portal, the little-game-that-could, really is. Between its flawless execution of its game mechanic, the meta-narrative inherent to GLaDOS and the way games are designed and played, and the unbelievable impact it had on video-game stories and the industry writ large, Portal is perhaps one of the most important games of the last fifteen years. Full disclosure, Dear Reader: before we went to PAX South 2018 and discussed this game and its many merits with a large group of gamers, I was fully ready to deny Portal entrance into the Video Game Canon. However, because of the collaborative discussion we had, I completely changed my mind and was able to think about this game in incredibly new and interesting ways. The Video Game Canon is meant to be a communal effort, and that has never been made more apparent to us than after our panel at PAX South. Cheers to you, PAX, and cheers to Portal, the newest entry in the Video Game Canon!