Why is it that so many adaptations involving video games tend to fail?

Whether it’s a game becoming a film or vice versa, the term “adaptation” alone can send chills down any gamer’s spine, especially as adaptations have become increasingly profitable within the current cultural zeitgeist. In an age of remakes, reboots, retellings and the rest of the “re” rabble, adaptation provides a refreshing alternative to the practice of telling old stories in new ways—but only if it’s done right.

To better contextualize the position of video games within this phenomenon, the following essay will define what an adaptation is, offer a theory of what it means to successfully adapt one work into another medium, and specifically identify the challenges and opportunities unique to works being adapted into video games. The central example used to demonstrate a successful adaptation will be Rockstar Games’ 2005 adaptation of the 1979 cult classic film The Warriors, but several other titles from different mediums will also be discussed.

For our purposes, there are several key, interrelated definitions that must first be established. An adaptation is a story that was created with the goal of capturing the spirit of an existing story in a different storytelling medium. The spirit of a story is the constellation of storytelling elements that most directly determine its overall shape, feel, and tone, to the extent that the meaning of other elements of the story essentially refer to the story’s spirit. To call back to a previous essay of mine, the spirit of The Witcher 3 is the constellation of (1) Geralt’s growth as an individual, (2) the hard choices he must make, (3) the consequences of those choices, and (4) how he feels about those choices and consequences. The meaning of everything else in the game (the NPCs, the music, and even the gameplay) essentially refers to at least one of those four elements; e.g., the setting is only meaningful to the story insofar as it reflects Geralt’s inner nature, his growth, and his feelings about his choices.

With this in mind, we can establish that an adaptation is a successful adaptation only if it succeeds at its inherent goal: capturing the constellation of storytelling elements that most directly determine an existing story’s overall tone, but in the context of a different storytelling medium. If one element of a story’s spirit is unique to its storytelling medium (e.g., the novel format of The Lord of the Rings is essential to its meandering, dense descriptions and worldbuilding), then it can only be successfully adapted if that part of its spirit is replaced with a storytelling element that is unique to the adaptation’s new medium (e.g., the visceral immediacy of a visual medium like film allows Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy to compensate for the lack of textual detail with cinematography).

We can refer to this process as translation, because adaptation is as intricate a process as translating a text from one language into another. Adept adapters don’t rely on an impossible vision of exact replication: the artistry of adaptation lies in the ability to approximate, reshape, and recalibrate a story in order to faithfully represent its spirit within a new medium. Every art form is an entire language unto itself, replete with its own syntax, diction, and turns of phrase, and trying to literally replicate all of these things in a different art form is futile.

As the English writer Anthony Burgess once noted, “Translation is not a matter of words only: it is a matter of making intelligible a whole culture.” In our case, we can replace the word “culture” with “spirit,” as defined above.

Why Many Video Game Adaptations Fail

When it comes to the language of video games, adaptation is often considered a dirty word. To understand why, one need only look at the parade of ill-advised games based on movies that sought only to coast on the popularity of their source material – looking at you, E.T.

Perhaps even more disheartening are the films based upon video games: some fail due to their inferior versions of the source material’s central characters (Super Mario Bros.; Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time), others because they cut-and-paste the game’s world and characters into generic film formulas (Hitman: Agent 47; Warcraft), and a handful simply because they came slithering forth from the warped mind of Uwe Boll.

But the most common reason for a lack of quality in these types of adaptations is that they are simple cash-ins created over a very limited period of time. In the gaming world, a limited development cycle means that developers have less time to create a story with breadth, depth, and fully-realized characters.

But in trying to quantify this cloud of incompetence, there is one fundamental issue that often goes ignored: video games are inherently an interactive medium that requires audience participation to function, whereas film and television are more passive. Many adaptations fail to understand how substantial that component of agency is to any given story, character, or world – consequently, they fail to compensate for that loss, and the end result is weakened. In other words, the cardinal sin that many adaptors commit is failing to utilize the possibilities made available by one of the most defining characteristics of video games: agency.

Think of 2002’s Enter the Matrix. Between the ultra-cinematic cutscenes, the motion-capture technology that allowed the real-life movements of Jada Pinkett-Smith to light up your TV screen, and the comically-explicit involvement of the Wachowskis in its development, it’s clear in retrospect as it was at the time that it was a game more interested in being an extension of a film franchise than a game in its own right. These things suggest a game made for a passive audience, not a player with agency. As a result, Enter the Matrix couldn’t escape its cinematic origins enough to ever properly establish itself as a new artistic entity.

But not all adaptations fall into this trap.

Enter The Warriors

When Rockstar Games first announced in the early 00’s that they’d begun developing a video-game adaptation of the cult classic film The Warriors, the general reaction was understandably mixed. On the one hand, many gamers had never even heard of the property. On the other, you had diehard Warriors fanatics who were either apprehensive about their beloved story being revived or irrepressibly excited about the potential of such a venture.

One thing that both the devotees and the uninitiated alike could agree upon was that with Rockstar in charge (albeit a Canadian division of the publisher), there was good reason to be confident in the end result. After releasing one of the most successful video games of all time in Grand Theft Auto III, the developer had racked up two more slam dunks with its sequels, Vice City and San Andreas. In the eyes of many, they could do no wrong, and so the announcement of yet another game focused on gang warfare made sense on a variety of levels.

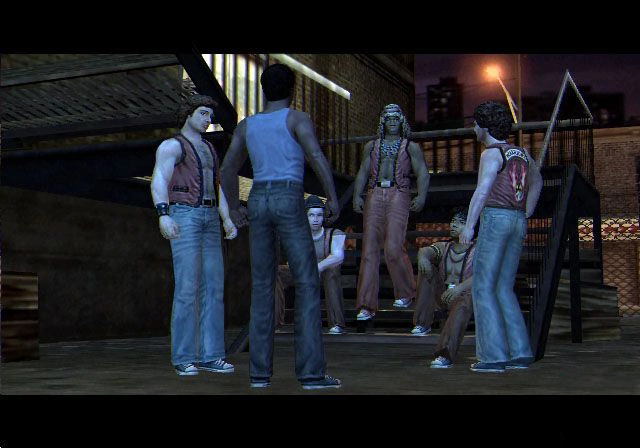

But when The Warriors video game (hereafter referred to as TW) finally hit stores in October of 2005, the finished product only resembled Grand Theft Auto in outward appearance. Sure, it featured a plot focused on an illicit underworld, a cast of criminals, and missions based on destructive mayhem and petty crime, but beyond these superficial similarities, TW differed from its predecessors in substantial ways. There was an entire gang of characters to play as rather than just one protagonist, a classic beat-‘em-up style of play dusted off from the arcade hits of old, and a unique visual aesthetic in keeping with the zany, vibrant source material.

Far from being a bare-minimum translation of the movie’s plot into video game form, TW built upon the mythos of the film with additional storylines and characterization, breathed life into the myriad of gangs only hinted at in the movie, and established its own distinct identity with its engaging, dynamic gameplay. That last point is the most crucial to this essay: although the additional worldbuilding is engaging, what makes TW a successful adaptation is that not only does it translate the film’s spirit effectively, but it also succeeds as a video game in its own right.

Before dissecting that, though, it would be prudent to examine the source material.

Understanding the Spirit of The Warriors Film

First, we must understand that The Warriors film is based upon a 1965 novel by Sol Yurick, which itself is based upon Xenophon’s Anabasis, one of the classics of Ancient Greece. Unfortunately, there isn’t space enough in this essay to assess the film as an adaptation of the novel, nor the novel as an adaptation of the classic. Rest assured, however, that Yurick’s book is only distantly and loosely based upon Anabasis, while Hill’s cartoonish film is mostly disconnected from the deeper themes of race, sexuality, violence, and crime that the novel explored with nuance. Right now, we’re interested only in the film as it relates to the video game.

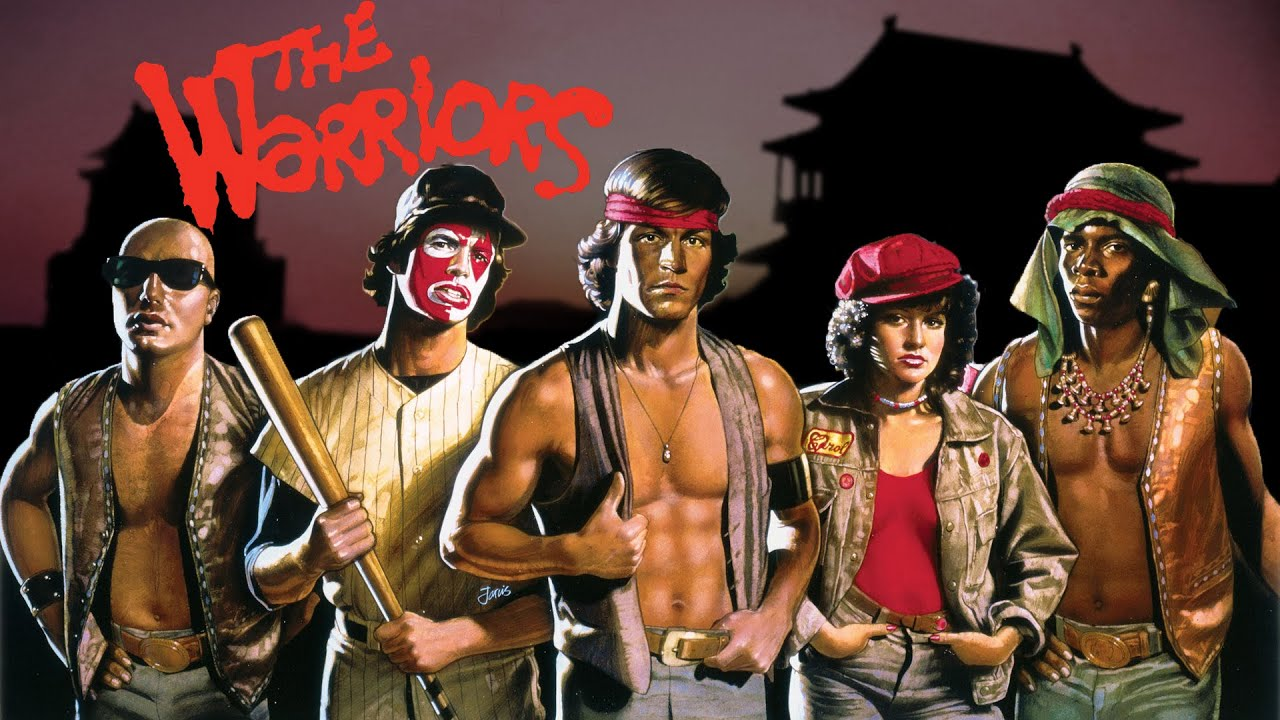

The Warriors become a cult classic primarily due to its unique visual aesthetic. Walter Hill portrayed a New York City populated by legions of colorful gangs, as multicolored in their fashion as they were multiethnic in composition. Skinheads, bikers, cholos, and other street toughs appeared alongside mimes, kung-fu warriors, and face-painted baseball fanatics: each crew had a look, and each look suggested an entire world and culture outside of the movie.

It’s precisely through utilizing that mystery and potential that The Warriors was able to construct a singular, engaging world without having the fill in all the blanks with dry details. What makes this approach especially effective is the setting: the enigmatic nature of the gangs is offset by the looming presence of New York City, one of the most well-established locations in cinematic history. Shot on-location, the cinematography allows the alleys, subways, parks, roadways, and tunnels of the city to provide a gritty contrast to the flamboyant gangs.

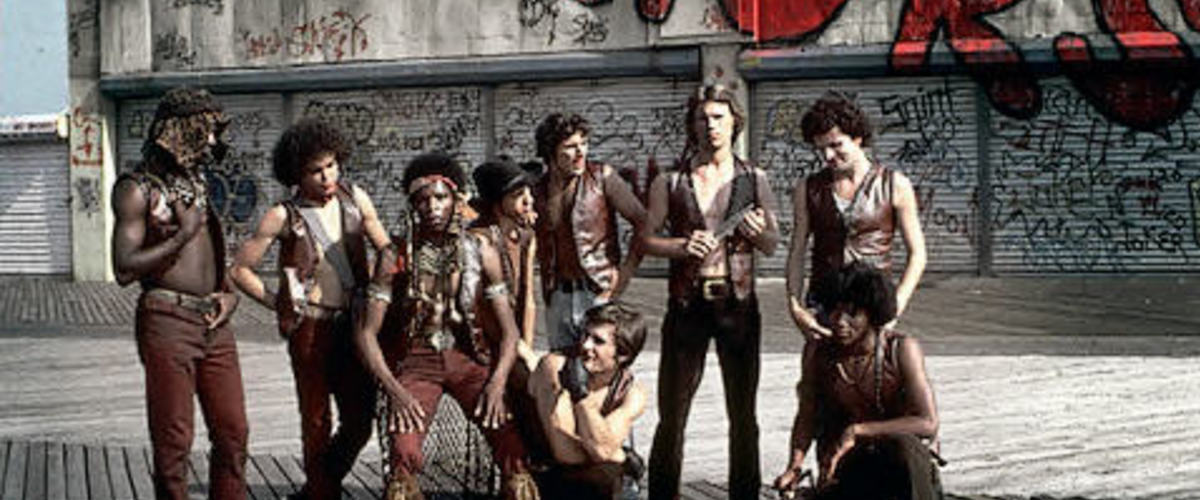

But if the visual dynamic of The Warriors is its standout feature, other key aspects have contributed to its longstanding relevance. The core cast stitched together a charisma and charm befitting the us-against-the-world story of their characters, even when their individual acting chops weren’t quite up to snuff. From stoic leader Swan to gangly street artist Rembrandt, amiable Vermin, and even the aggressive, tough-talking (if alarmingly misogynist) Ajax, the youthful crew came off as believable and sympathetic, a ragtag collection of castoffs suddenly and wrongfully forced to fend off every gang in town. Equally compelling is the character of Mercy, a wayward young woman who attaches herself to the group as much out of boredom as a desire to escape her circumstances.

Together, these characters are emblematic of the film’s spirit of hopeful perseverance, fighting and fleeing their way back to Coney Island even as they are pursued by legions of berserk boppers. In the end, and after losing some of their brethren to rival gangs or the cops, the Warriors successfully clear their name and walk off into the proverbial (and literal) sunset.

To return to our definition from our introduction, I’d posit that the spirit of The Warriors is the constellation created when (1) the colorful aesthetic and (2) the gritty, realistic New York setting combine with (3) the charismatic cast of characters to tell (4) the thematic tale of bold, willful resistance in the face of impossible odds.

The next part of this article will examine how the developer approached translating each of the four elements of The Warriors’ into a video game format. Through what methods did Rockstar manifest these elements in their story,, and if they couldn’t, in what ways did they compensate for those losses? Additionally, did Rockstar fully utilize the medium of video games into which they were adapting The Warrors? If so, how?

(1) The Armies of the Night

As mentioned above, a huge strength of The Warriors as a movie is the way it utilizes the power of mystery and suggestion. Its expansive world of flamboyant gangs is made richer and broader by the viewer only receiving bits and pieces of that world: a few shots of one gang here, a fight scene there. One of the most immediate challenges facing TW, therefore, was the same problem faced by many prequels and sequels: if a character or a group was effective precisely because we don’t know all that much about them, then how can a story entirely about filling in those blanks be successful?

The answer is to lean hard into filling those blanks, and thereby turn a supposed weakness into a strength.

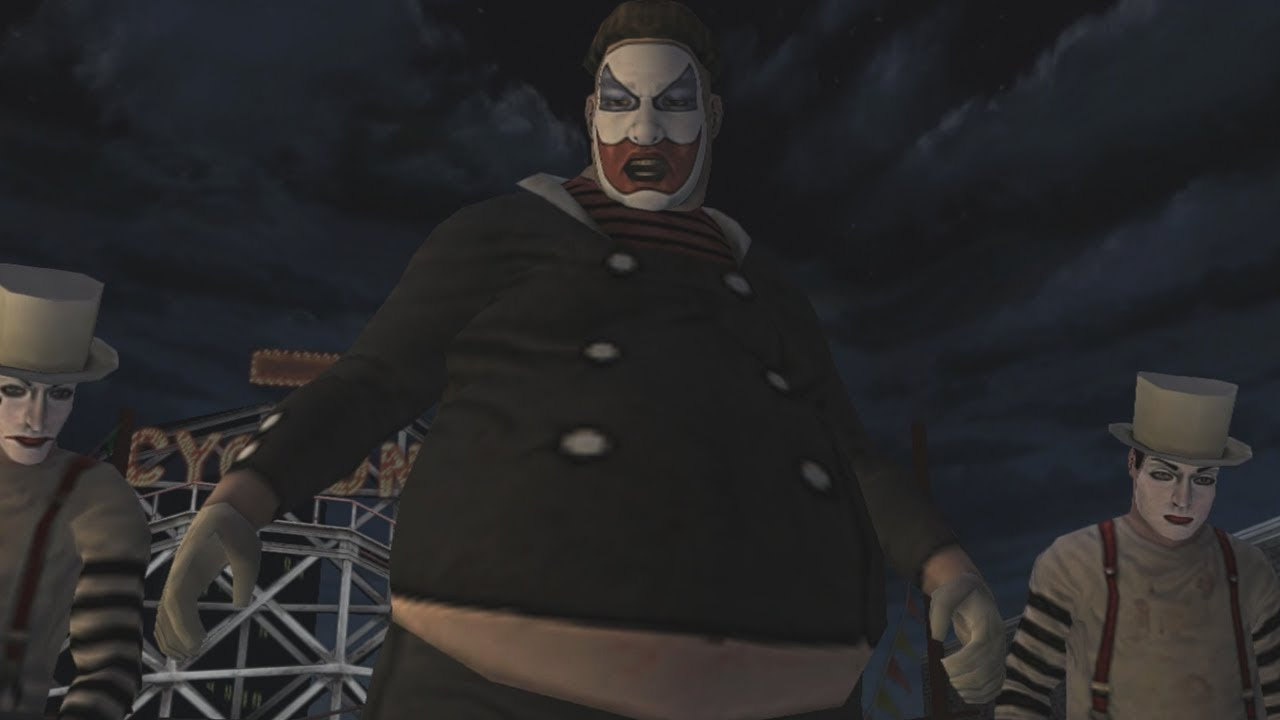

In this case, almost every gang mentioned or referenced in The Warriors gets their own mission or subplot in TW. The Turnbull ACs are rounded out from being stereotypical skinheads to being a rowdy gang of punk-rock-loving, violent toughs. The Hi-Hats, who appear for just a few seconds in the film, get not one but two lengthy missions elaborating on their look, their culture, and their stuttering, Shakespearean leader, Chatterbox.

It’s not only this willingness to expand on the characters and the world that contribute to the TW’s success as an adaptation, but also the substance and originality that these expansions contain. It’s one thing to present a series of reference points and visual cues so that informed players can say, “Oh, look, it’s the mime guys from the movie.” It’s another to create intricate missions about and surrounding those mime guys, to the point where some of the most fun and exciting content in TW exists within those missions, whether it’s the adrenaline-inducing graffiti competition of the gang’s first mission, or the kitschy spookiness of their second, which takes place in an abandoned haunted house. Far from being simple fan service, TW plays down what it lost from its source material by playing up what it can uniquely do as an adaptation.

We can see this methodology put to work a second time in the case of the next element that constitutes The Warriors’ spirit.

(2) Big Apples to Small Oranges

How can one replace the one-of-a-kind setting of New York City? In The Warriors, you can almost smell the subway cars, or feel the paint dripping from the graffiti. Hill made extensive use of on-site shooting, so much so that NYC feels almost a character in itself, as it so frequently does in movies set there. This is one area where video games have not been able to keep up: only a handful of games have delivered anything close to an authentic New York City (most recently, that certain Spider-game).

Given the technological limitations of the time, Rockstar knew that they couldn’t hope to deliver an NYC that looked true-to-life. So, why not go the opposite direction and emphasize the unreality of the world? Instead of spending all your resources on graphics so that players can stare at a better-rendered alleyway, why not make them engage with that alleyway for reasons beyond the visual? Instead of trying to make a game that looks like it’s set in New York, why not make a game that plays well in New York?

Why not beat-’em-up?

Characterized by side-scrolling stories featuring unending waves of enemies to be punched, kicked, and smacked into submission, beat-‘em-ups were a natural extension of the traditional fighting games that dominated arcades of the classic gaming era, reaching their zenith in the one-two punch of arcade classics Double Dragon and Final Fight (released in 1987 and 1989, respectively). The ‘89 cult favorite River City Ransom also received substantial acclaim for helping grow the genre by introducing elements borrowed from role-playing games. However, the following decade was less kind to beat-‘em-ups, as the onset of console gaming led to a plethora of new genres unbound by the constrictions of an arcade format. Still, the success of certain titles (like Sega’s Streets of Rage series) helped the genre endure through the ‘90s.

It’s worth noting that throughout this period, titles like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Batman Returns demonstrated the genre’s unique fit with cartoonish, comic-book aesthetics: the super-powered protagonists and colorful enemies inherent to these franchises made them ideal candidates to utilize the genre’s formula. With this in mind, The Warriors and beat-‘em-ups were a match made in brawler heaven.

For starters, the genre gave Rockstar a means of adapting the film without being too derivative of their back catalog, while simultaneously tipping the proverbial hat to the medium of video games and its rich history. But as I’ve alluded to, this choice of genre is also an excellent way to compensate for the lack of the real-world NYC inherent to The Warriors. Whether in tenement houses, subway bathrooms, Soho art galleries, or Chinatown markets, TW opts to deliver a breadth of NYC locations that might not look the prettiest, but are ludicrously well-suited to the game’s brawler mechanics. Breakable environments, an extensive range of objects and items to use as weapons in a street fight, or even just the pedestrians who wander about ripe for mugging: all of these things point to how Rockstar was able to benefit from their unique setting without being hamstrung by its lack of realism.

In other words, rather than reshaping their game in order to better represent NYC, the developer reshaped NYC to better represent their game. It’s this mode of thought that is usually indicative of a successful adaptation.

(3) Questions of Character

How can a video game released more than thirty years after-the-fact recreate the onscreen chemistry of a movie’s central cast?

The answer is multifaceted. For one thing, by employing the talents of James Remar to voice his infamous character Ajax, Rockstar created a direct link between the movie and the game that helped bridge the distance. But while many video-game adaptations would stop there, the developers behind TW astutely realized that they had to bring more to the table on a character level in order to compensate for the loss of, say, Michael Beck’s steely-eyed stoicism, or Marcelino Sánchez’s youthful naivety. And, in the Flashback Missions of TW, they did.

Interspersed between the main plotline of TW, there are four individual Flashback Missions, lettered A, B, C and D. Each exists outside of the central story and takes place at a specific point in the past when a central member of the Warriors first became inducted into the gang. While these missions are fun and involving from a gameplay perspective, they are tangential to the main plot. Their value, then, is how they function to add depth of character to the story as a whole.

Whether it’s how Cleon and Vermin initially rebelled against their former gang to create the Warriors from scratch, or how Fox successfully completed a covert operation to earn his stripes, these Flashback Missions add layers of complexity to TW’s central characters that a mere combination of voice acting and polygons couldn’t accomplish. In this way, we again see how TW makes up for its lack of screen acting’s immediate humanity by utilizing a characteristic of video games (i.e. side missions) to create depth of character.

Nor is this approach isn’t restricted to matters of character: and can also be applied to the plot itself.

(4) What it Means to Come Out and Play

I’ve already established the beat-‘em-up formula that dominates TW—a formula reinvigorated by a dense urban setting optimized for brawling. Each level takes players on a semi-linear path through an NYC neighborhood, its breakable environment full of boxes, bottles, and bricks to bash over cops and gangsters alike. But the game makes an effort to diversify its beat-’em-up style by incorporating different types of play to elaborate upon its foundational premise of gang warfare. Tagging over other gangs’ logos with spraypaint, breaking into cars to steal tape decks, even wild chases that involve button-tapping to avoid gangs or police: all of these things create a diversity of experience that helps impress upon the player the kind of lawless chaos intrinsic to the spirit of The Warriors.

Taking these ideas further still is the Warriors’ warehouse hangout (which serves as a hub in the game’s world) and the semi-open-world Coney Island outside of its doors, where players can engage in a variety of minigames and exercises to increase their strength and agility for main missions, unlock cool items and characters for multiplayer mode, and otherwise engage with the world the Warriors inhabit outside of the confines of the game’s central plot. In all of these aspects, we can see how TW again implements the methodology of aggressively-filling-in-the-blanks—only, this time, we’re learning more about our protagonists rather than rival gangs: how do they actually operate as a street gang? What is it they do around Coney Island? How do they earn their money—or, more importantly, their reputation? To these questions and many others, TW once more offers satisfying answers to questions posed implicitly by the film using modes of play unique to the medium of video games.

But to understand how TW successfully conveys the thematic heart of its source material, we must look to the game’s story mode.

Rather than simply presenting an interactive retelling of the movie’s exact plot, the game’s narrative begins a full two months prior to the events of the film. Structurally, this is enticing for players already familiar with the movie because it invites the question, “How do we get from here to there?” In that way, a certain depth of narrative is inherently promised by the game’s structure—but more pertinent to this article is the necessary interactivity that this structure entails.

By playing the game, the player is actively contributing to the chain of events leading to the film, thus actualizing the events of the film by playing through those of the game. In other words, through an innovative narrative structure, TW again emphasizes a defining characteristic of its new medium: agency. This principle carries through in the actual events of the story mode, as well: at the game’s outset, the Warriors are a minor-league gang, extremely low on the totem pole of New York City criminality. Then, as the player completes more missions, the Warriors grow in size, influence, and repute, eventually becoming big enough to earn an invite to the meetup in Van Cortlandt Park where the film’s inciting incident takes place.

Again, the implication here is clear: it’s the responsibility of the player to help the Warriors of the game become the Warriors of the film.

Found in Translation

All in all, TW is a near-perfect adaptation. Already faced with the difficulty inherent in bringing a decades-old cult classic film into the modern day as a video game, the developers at Rockstar smartly understood that they had to emphasize the merits of the medium in order to make up for losing the defining characteristics of film. Whether in its expansion and deepening of the original story, its attention to character detail, its exaltation of the beat-‘em-up genre as a way of altering the role of setting, or, perhaps most importantly, its constant underscoring of the interactivity of video games, TW successfully translates the core spirit of The Warriors while managing to stake out its own individuality, as a game and as a work of art.

In the face of all of that, only one question remains: Can you dig it?