The following is part of Now Loading, a series that renders verdicts on whether or not your favorite video games deserve a place in the canon of works that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. Read the series’ full mission statement here.

Compared to Sonic’s other beloved Genesis-era titles, Sonic CD is an oddity, to say the least. It can be completed within ninety minutes on a first attempt, without even trying to speedrun. Its bosses are easy, its stages are short, and its plot is a rudimentary affair constrained by having only four named characters. So, why exactly is Sonic CD such a richly atmospheric work and a fantastic example of worldbuilding?

I’m usually not one for cheesy metaphors, but sometimes they’re just what the situation calls for. This is one of those times, so bear with me while I explain (in a roundabout fashion) what makes Sonic CD so unusual.

The Best Swimming Pool

Imagine you see an ad for a new swimming pool—specifically, the world’s biggest swimming pool. There’s no picture in the ad, but your mind paints a picture of a pool stretching for miles. You can dog-paddle for hours without having to turn around. You absolutely can’t wait to go to the pool and see it for yourself.

When you actually get to the pool, you’re confused: the pool is average sized; if anything, it’s a little on the small side. The lifeguard insists the statement in the ad is true—the pool is hundreds of feet deep, so it is the world’s biggest pool. Any given lap, however, feels rather short.

At first, you consider simply leaving, but you decide to the give the pool a try, since you’re there already. At first, swimming seems as average as it’s ever been in any other pool. But eventually, you realize that having so much depth to work with lets you make every lap different; for example, you can kick off the wall and point downwards without having to worry about hitting the floor with your head.

At the end of the day, even though each lap isn’t extraordinary on its own, being able to use the depth to make each lap interesting is enough. You’re happy you came, and you plan to recommend the pool to your friends.

Sonic CD was the flagship title produced for the Sega CD, a device that mounted on a Genesis and allowed for the use of CD-based games. No longer were the worlds of Sega constrained to the memory limitations of a cartridge. The Sega CD promised better-looking, better-sounding, and overall better content than that the lowly Genesis could run on its own.

The Sega CD, mounted on the Sega Genesis.

Would this mean that all the major Sega franchises would have their best installments yet on compact discs? Unfortunately not: high price and a library stuffed with low-quality FMV games (Night Trap, anyone?) meant that the Sega CD would have a short and unsuccessful lifespan, relegating gems such as Hideo Kojima’s Snatcher to cult-classic status. Despite belonging to a beloved series at the height of that series’ prominence, Sonic CD also fell into relative obscurity until 2011, when the game was remade for modern consoles.

Sonic CD uses the expanded memory capacities of the CD format to their utmost, and the developers clearly poured staggering amounts of effort into developing assets and music for the game. Any one playthrough is simple, but the world hidden in the game is a fascinating one. Just like the pool in my metaphor, exhaustive effort went into making a game that is short and easy to play through, but which also hides a lot of depth when one is ready to dive in.

Story and Characters: Out of This World

Although it was released after Sonic 2 and before Sonic 3, Sonic CD tells a separate story with no ties to the “Death Egg Saga” of which 2 and 3 are a part. 2 and 3 are presented as Sonic exploring two new islands for the first time, while working to take down series’ villain, Eggman; CD takes things to a whole new level, however, by taking place on a new planet, providing a surreal and creative realm for Sonic to explore.

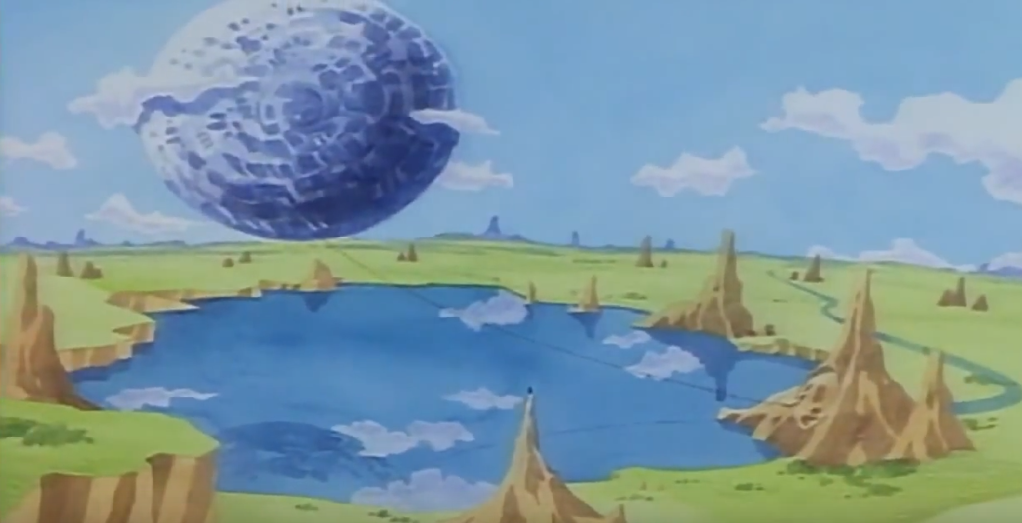

Majora’s Mask in reverse: Little Planet wants to break free from its chains and leave Earth.

Sonic’s world is occasionally visited by a miniature planet floating in the sky, dubbed “Little Planet,” rumored to cheat the laws of spacetime in strange ways. When Little Planet appears once again, Sonic races to a high vantage point to take in the view, but discovers the planet encased in metal and chained to the Earth by Eggman. Sonic races up the chain to learn the secrets of Little Planet, and to fend off Eggman’s odious influence all the while.

Sonic quickly discovers that Little Planet hosts seven mystical Time Stones, whose presence enables time travel. By hitting special icons and maintaining high speed for several seconds, Sonic can make like a modified DeLorean and jump into the past or future.

Eggman has established his influence in the past, which has made it the case that the past, present, and future belong to Eggman. Sonic must either travel back to the past on every part of the planet and set things right (requiring exploration), or instead assemble all of the Time Stones (requiring skill). If he accomplishes neither, then Eggman will use time travel to undo any of the good that Sonic has done.

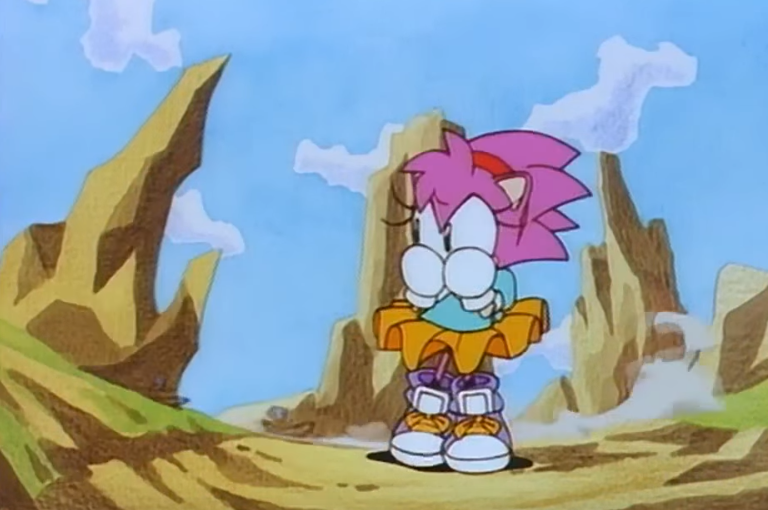

Along the way, Sonic meets his iconic doppelganger, Metal Sonic, and his romantic interest, Amy Rose, an obsessive fangirl whose advances Sonic does not reciprocate in the slightest.

Metal Sonic is a uniquely threatening villain because of the way his rivalry with Sonic plays out. He is Sonic’s rival in speed, rather than in combat; his boss battle is a race, rather than a fight. By taunting Sonic with the danger of being too slow to catch his metal doppelganger, Eggman is clearly out to take Sonic’s pride as well as his life.

Less stellar is the introduction of Amy Rose, who creates a reverse Mario/Peach dynamic. Sonic finds him desperately trying to outrun Amy; he saves her from kidnapping, but the literal instant that her safety is assured, he dashes off into the distance. The irony of this dynamic is more interesting in concept than in practice, unfortunately. Throughout the game, Amy Rose goes from stalker to kidnap victim to stalker, making strides neither for herself nor for female representation in the franchise.

Not pictured: Sonic (you can see the dust he’s kicked up running away from Amy).

Gameplay, Music, and Visuals: Deep Dive

Here lies the heart of Sonic CD, the fruit of the developers’ labor. Much of the richness of detail is easy to miss if one is hurrying by, but this richness is why the game should be played. The level assets and music tell a story all their own.

In most Sonic games (as in many other games), the villain plans to take over the world Since Sonic defeats Eggman every time, though, we rarely get to see what exactly it is that Eggman would do with a world under his control. Sonic CD uses its time-travel mechanic to show us what exactly would come to pass, by letting Sonic time-travel into a future where Eggman rules supreme (not dissimilar to the future imagined in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time).

For all of his elaborate schemes, Eggman doesn’t seem to be the best emperor ever to rule a planet. If Sonic visits “Bad Futures” while traversing levels, technology advances in the worst way possible. Lush greenery and bright colors give way to wilting husks, skies dark with thunderstorms, water turgid with pollution, and rusting machines. A once-upbeat city has become a dystopian hellscape, with an Eggman statue erected at its center; a mine once filled with quartz has been depleted and left to rot.

Through seeing these futures, the player realizes that Eggman is not just evil: he is evil and incapable of managing his empire. A future ruled by Eggman is not just a scourge that will pass—the planet is dismal, depleted, and dying.

Palmtree Panic, Bad Future.

If Sonic is able to destroy machines hidden by Eggman in the past, these “Bad Futures” become “Good Futures.” Futuristic technology still has a place in the “Good Future,” but it aims to help life thrive, rather than drain life away. Trees now have elaborate filtering machines to purify water; a hazardous factory has transformed into a toy factory; Eggman’s headquarters have been reclaimed by nature, becoming a habitat for all sorts of animals and plants.

More than just being easy on the eyes, the Good Futures clarify the Sonic franchise’s message regarding environmentalism. The recurring struggle between nature-loving Sonic and technology-obsessed Eggman have led some to interpret the Sonic franchise as staunchly anti-technology. Sonic CD shows this is not the case: technology plays an integral role in an ideal world, if handled with care and concern for the environment.

Palmtree Panic, Good Future.

The game’s music heightens the atmospheric contrast between Good and Bad futures. Past, Present, Good Future, and Bad Future eras all receive a remix of each level’s theme. An upbeat tune filled with determination in the Present might give way to an out-of-tune, downbeat version in a Bad Future, or transform into a peaceful ambient remix in a Good Future. (The game received a different soundtrack when released in America. Both the Japanese and American soundtracks have their fans and detractors, but given the Japanese soundtrack was more directly tied to the creation of the game, it’s the one I’ve chosen to spotlight here.)

It’s in this context that Sonic CD is easy to complete, if you’re willing to condemn each area of the planet to a Bad Future. Just rushing through is easy—after all, Eggman has no real need to kill you, since he can use time travel to undo whatever impact you’ve had on the Little Planet. Given the franchise with which Sonic CD is associated, players likely feel they have to go fast… which is precisely what Eggman wants.

Both paths to the game’s true ending require negotiating levels with care: stockpiling at least 50 Rings by the end of each level and completing challenging Special Stages, or finding robot manufacturing plants in the earliest era of each level. This involves diving into the labyrinthine design of each level, even though that labyrinth can be bypassed by those unconcerned with fixing the Bad Futures.

This is the genius of the game’s time-travel structure: rather than having to engage in difficult tasks because you have to, you do it because you want to save the world. You are constantly being shown the positive impact you have on the planet by witnessing Bad Futures turn into Good Futures.

The sheer scale of the game is astonishing. Every level has four completely different variants, each with unique graphics, music, and level layouts, that can be reached at will through time travel. It is infeasible that anyone will ever be able to see every part of every era in every level, but what matters is knowing that all the content is there. It gives the impression of a living world, and a world that is worth keeping alive.

Little Planet’s Present, Good Future, and Bad Futures—one planet, but three worlds.

Impact on Video Gaming and Culture: A Gem Held to Light

For nearly twenty years, Sonic CD remained a fairly obscure game, receiving a few suboptimal ports (most notably the Sonic Gems Collection for Gamecube and PS2 in 2005). The game developed a stellar reputation, and although few had played it, many were intrigued.

This changed in 2011 when the game was rebuilt from the ground up to run on modern consoles and was released across PC, handheld, and console devices. This release received high praise, largely due to the optimization of the game.

Since then, however, opinion on the game has been divided. Many claim that it is overrated, encouraging others to distinguish unique gameplay from enjoyable gameplay. Regardless, Sega has accepted Sonic CD into the “canon” of classic Sonic games, revisiting its ideas and content in games like Sonic Generations, Sonic 4: Episode 2, and, most recently, Sonic Mania.

My two cents: Sonic CD places a heavy emphasis on exploration in the context of levels that are not conducive to wandering. From a gameplay perspective, many of the levels feel like uncomfortable compromises between Sonic’s trademark roller-coaster setpieces and segments lifted out of a Metroidvania-type game.

As I’ve said throughout this piece, having to work for a payoff is important to the experience of Sonic CD, but this does not fix muddled level design. It is probably telling that 2D Sonic games since Sonic CD have largely steered clear of exploration in favor of speed, with a handful of questionable exceptions (e.g., Sonic Advance 3).

BONUS LEVEL: A Job Poorly/Well Done

The final act of each area takes place in the future. This means that, at the end of each area, you will be forced to see just what impact you’ve had on it. The subtle storytelling potential of this structure is utilized to its maximum in the game’s final level, “Metallic Madness Zone 3.”

As is to be expected, this level has two variants: a Good Future and a Bad Future. Each evokes strong emotions. The Good Future has clear blue skies; greenery uses Eggman’s machinery as a makeshift trellis; and slow, happy music tells you that your battle is won. Just one last confrontation, and the day is yours.

On the other hand, in the Bad Future, everything is rusty, and (at least in the Japanese soundtrack) the music actively mocks you for your bad performance! A synthesized voice announces, “YOU CAN’T DO ANYTHING, SO DON’T EVEN TRY. GET SOME HELP. DON’T DO WHAT SONIC DOES. SONIC, DEAD OR ALIVE, IS MINE!” You get the sense that you’ve really gone astray, and that, if you defeat the final boss, you’ve won the battle while losing the war.

Sure, Eggman is laughing in both timelines, but he’s only justified in the Bad Future.

VERDICT: On Compact Disc, A Compact Discovery

Mechanistically, Sonic CD can’t hold up against Sonic 2 or Sonic Mania, the latter of which remakes some of Sonic CD’s levels with better-flowing level design. Were we building a canon of level design, Sonic CD’s chances of admission would be slim. But we’re building a storytelling canon, and in that regard, Sonic CD outshines Sonic’s other classic games (and his modern ones, but that’s a different story).

The Sonic franchise is often mocked for a “press right to win” approach to gameplay, where simply holding right and occasionally jumping will quickly deposit Sonic at level’s end. Played today, Sonic CD is both an acknowledgment and deconstruction of that critique. Sonic can breeze past the sights and sounds of Little Planet with practically no effort, and, indeed, new players will likely do just that (compounded by the game’s unfortunate lack of explanation for its time-travel mechanic). But Eggman’s plan hinges on just that: Sonic’s effort will by default be minimal, and his minimal impact can be undone with time travel.

To save the world, Sonic and the player will both have to do things they don’t have to do to complete the game—and they’ll do these things because they should be done. In so doing, Sonic graduates from an impatient woodland mammal to a hero who can truthfully say that he saved a planet.

The obscurity of Sonic CD likely hindered its ability to be directly influential on contemporary video games. Regardless, it is still remarkable for preceding such games as Ocarina of Time in exploring the storytelling potential of time travel, and exploring the same world in different eras. For this reason, I do believe that Sonic CD should take its place in our canon.

Welcome, Sonic CD; it’s good to have you here.

Skylar Cohen will be featured as a panelist in “Which Games Belong in the Video Game Canon?”, one of three panels With a Terrible Fate is offering at PAX East 2018. Don’t miss this chance to learn more about the series and join us in a live discussion about whether an audience-selected game belongs in the canon!