Having read comics and played video games throughout my life, I have noticed that the two media rely on visual interaction in a similar way. Comics let the eye travel and let readers explore settings within the panels, giving readers a sense of direction and journey that words alone cannot. Artists and writers create most of the visual aspects of the story’s world, so the reader’s job is to traverse pages and discover the content between the pages. Video games take the exploration of comics a step further: once players figure out the main goals of the narrative, they can choose to follow the designed path, or stray off of it. The game does not confine a player like a comic confines its reader, who has to follow specific panels depicting specific places: players go where they want, even if it is the wrong way. Now, the more linear a game is, the less this is true, so this applies specifically for explorative video games: games where more than one path is available, games that give players little guidance on how to complete the game, and games where the choices a player makes determines the ending a player gets. The evolution from comics – panels with limited view with a set narrative – to games – moveable panels with a greater player interaction- follows a simple rule: the more a comic allows readers narrative exploration and deviates from limited visual framing, the more the medium becomes like a game, allowing player interaction and control over certain characters’ actions.

To see this transformation, we must first discuss print comics to understand both framing and interactive narration.

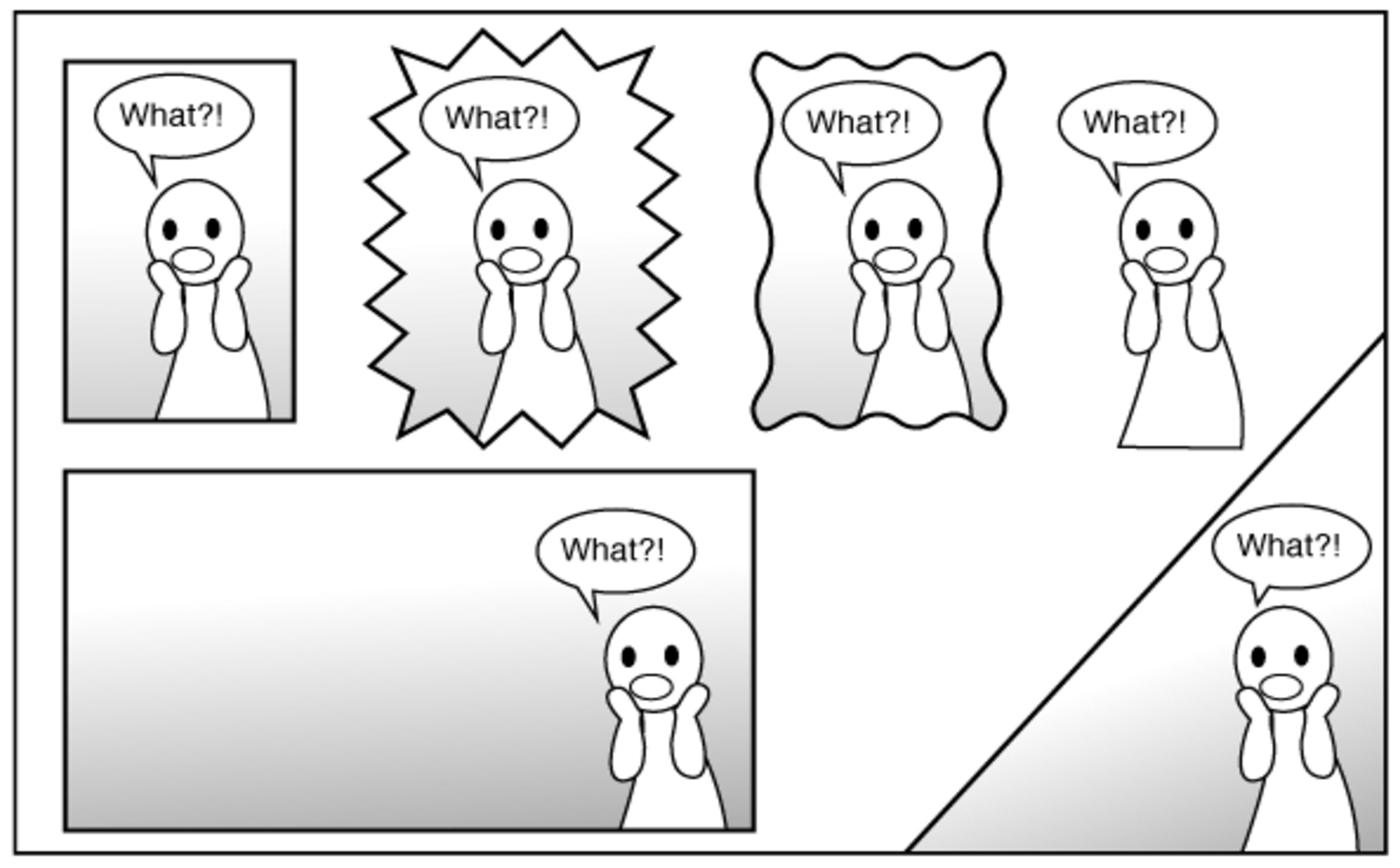

From Berntsson, Sara: “Create a Comic: How to Plan out and Layout your Comic.”

The frame of a comic contains a scene or part of an action. It can be a small box with black outlining that isolates certain moments in time, or it can be an entire two-page spread. The frame can show either an entire landscape that stretches on for miles, or it can show the smallest tear falling from an eye. In either instance, the artist cannot fit an entire world within the limits to the frame, so it is up to the reader to create the rest of the world in their imagination.

For example, in the beginning of Fabien and Kerascoet Vehlmann’s Beautiful Darkness, the characters all escape a weird, oozing liquid that floods their home; small panels show fragments of action, of people, and of the environment. Throughout the dramatic scene, the frame zooms in on the action, showing little of the claustrophobic space from which the characters escape. Because of the limited frame, readers can only guess where the characters are, envisioning something akin to a cavern or tunnel. Turning the page reveals one page-sized panel depicting the decaying and leaking environment: a young, human girl’s corpse (Vehlmann, 6-8). Here, the panel opens up, and the artist finally welcomes the reader to examine the comic in a bit more depth, with the shocking image consuming the page. The artist allows readers to see the entire image of a child’s corpse and thus wonder what the characters were doing inside the body in the first place.

Fabien and Kerascoet Vehlmann’s Beautiful Darkness, p. 5-6.

For print comics, the frame’ s immovable structure hides certain details from the readers, creating narrative suspense – not knowing where the characters are or the nature of the decaying environment – and reveals specific scenes and action only when the artist wants the readers to see them. The narrative of the comic is set: no reader is going to change what characters do or how they reach their goals. The frame then is the device that allows readers to “explore” the story by guessing what lies beyond the frame, and by figuring out the secrets the artist does not want the readers to know quite yet. Readers can only know the truth and entire narrative, though, if the artist allows it. Framing is the artist’s choice of perspective within a border. How did the artist picture this scene with a limited scope, and why? Usually, the answer to “why” is because the artist wants to create narrative suspense, as seen in Beautiful Darkness. As Scott McCloud states in his book Understanding Comics, “comics can be maddeningly vague about what it shows us. By showing little or nothing of a given scene, and offering only clues to the reader, the artist can trigger any number of images in the reader’s imagination” (McCloud, 86). Readers piece together the images the artist gives us and create the actions that were not shown, the settings that were not detailed, and all the images that potentially make up the rest of the comic’s world. If the reader sees everything that happens in a scene at the very beginning, then the thrill of reading the story disappears. There is no mystery to sustain the reader’s curiosity, and the comic becomes dull. Framing subtly keeps the reader on edge, not showing every detail of situations and thus letting the reader’s imagination create everything else that extends far beyond the frame’s border.

McCloud, Understanding Comics, p. 68. Be sure to check out this book for comic theory. I’ll be using his arguments in my later pieces as well.

If framing allows readers to expand on a given world, interactive narration lets readers go one step further. Interactive narration is when the artist lets the readers discover the story of their own. The story itself is set, and the readers cannot change what happens or how events occur; however, readers can move panels around, finding certain paths in the story until it leads to the conclusion, the ending the artists wants you to see. Comics in a web-based format provide this kind of reader interaction. “Click and Drag,” by Randall Munroe of XKCD fame, seems like short strip comic, consisting only of four panels. At first, the fourth panel seems lackluster for a conclusion, only depicting a scene of some rocks and a tree. In reality, through, the fourth panel extends into a grand world, but the frame only shows a small part of it. The reader must use the mouse to literally “click and drag” the panel around to see the entire world, one much grander and fuller of life than expected. Readers may scroll to the corners of the world, to the airy heights, or to the depths below the surface to see the full extent of the characters’ world, with the sad and the funny and the wonderful all in one ginormous panel. The only way this sprawling comic could have worked is on the web: if the author printed out the giant panel and gave it to people, it would not have the same effect, for the comic would not give the reader any sense of journey. By seeing the entire picture, the reader becomes a god, seeing everything, and cannot travel across the landscape as a normal adventurer. In this way, the moveable frame becomes a telescope, allowing readers to see only a small image of the much bigger picture. In print comics, the frame can seem like a limited view because it hides the rest of the world from readers (and then they have to use their imagination to create the rest of the picture), but, in an interactive setting such as the web, the frame becomes a tool to start a journey. A frame that shows only a small segment of the world forces readers to explore the rest, to choose a direction in which they will go, and to choose how fast or slow they will “click and drag” through the entire landscape. Many other web-based comics use animation and user interaction to create vast landscapes and complex narratives, pulling the reader even deeper into their worlds. The interactive frames in such comics allow readers to choose their own path and explore a world that they must discover on their own, one drag at a time.

Randall Munroe’s “Click and Drag.” Dragging the final panel with one’s cursor reveals the enormity of the world.

In both print and interactive comics, the frame usually depicts a 2D realm of images; a giant leap in the comic medium occurs when panels start moving in 3D space and the reader can control where the frame goes in such a space. This interactive framing happens in most Point-and-Click games. For example, in Hood: Episode 3, a game by the creator Hyptosis, the player starts inside a village, facing some of the locals. You can either talk to them or click the arrows leading deeper into the woods. Each click of the arrow takes you to a new scene, a new landscape, a new frame – the artist’s choice of perspective for a scene. Each jump to a frame indicates a player’s movement to the next area, making the game play like a succession of comic panels. Because the frames are part of an interactive medium, artists draw each scene with detailed environments, hiding clues in garbage piles or kitchen cabinets for the player to pillage. Some things can be picked up, such as shovel, and others objects indicate a riddle you must solve. At one point in the game, you find a tree with weird, moveable markings. It is a puzzle, and you know you must solve it in order to progress; but (presumably) you have no idea how to do this, so it is up to you to go back and find the answer, which you will discover by talking to a creature living in the woods (Hyptosis). In most Point-and-Click games, each time you click the arrows that move you to the next area, you discover a new frame to explore like interactive comics. But unlike the latter, the story does not continue unless the player acts: the game does not automatically give the next set of panels, nor is there only one way for a player to read the story. Players can get stuck in one panel, become lost in the world, or head in the wrong direction.

Hyptosis’ Hood: Episode 3.

Usually, Point-and-Click games follow one character, the main character whom the player controls, as he or she travels through a world and embarks on a grand quest. Most Point-and-Click games (as the name implies) relies on the player scanning the environment and clicking for any object, person, or path that could be useful, such as a hidden door, a bottle to carry the special water needed to grow a beanstalk, or a code carved into the tree that stands in the left corner of the screen. Point-and-Click games are all about searching for clues in order to progress; the games are essentially one giant puzzle that players have to solve, piecing together certain items and connecting plot points in order to complete the adventure. Some games function like Hood, where the player sees the world in first person, but in other games the player can see the character in third person. The transition of environments is always the same, though: players move from scene to scene exactly as they do in comics – with a frame by frame jump of perspective. The difference between comics and Point-and-Click games is that, in the latter, the player determines which frames to travel to. Point-and-Click games, then, are movable comic panels that the player visit several times and choose to be in; players discover the narrative and the adventure at their own pace.

While comics have a set narrative that readers cannot alter in any way, games allow players to roam around the environment and make the character act, if they choose to do so. Players can change certain elements of the story, such as what the player had when they arrived at a specific point in the game, or whether the character completed a side mission (a part of the game not relevant to the main plot). Some games even forgo most of the interactive landscape and focus on the interactive storytelling, leaving all of the main character’s choices – dialogue, quick decisions, moral obligations – in players’ hands (see A Wolf Among Us or The Walking Dead, both by Telltale Games – and both were originally comics). Some games, like side scrollers, coincide closer with comics because there is only one way to go: left to right. Other games, like open world games, greatly deviate from comics by providing a seemingly endless amount of paths to take. In the same sense, some comics start to act like games when they provide multiple ways for the story to end, giving readers paths of panels. These types of comics can also allow players to complete certain tasks that a character must do, such as spinning a cog wheel by spinning the mouse. Showing how comics can gradually convert into video games and vice versa shows how much one medium can transform into another and how the two mediums feed off of each other in terms of narrative, landscape, and reader/player interaction.

Daniel Goodbrey, “Never Shoot the Chronopaths” (check it out here). In the interactive comic, you are given three paths, or “strips,” to read, but all three converge into a jumbled impact toward the end. Afterwards, the paths branch out again; so, you have to read the comic more than once.

In future articles, I plan to analyze specific video games in their relation to comics, touching upon ideas such as framing, narrative interaction, and game design (how a player interacts and completes the story) in relation to visual design (how the player or reader sees the story) in both comics and game. I will compare video games to other interactive comics (or even print comics) to demonstrate the profound relationship the two mediums have and why it is important to cherish both. I will examine other Point-and-Click games (Deponia, Machinarium, Fran Bow), RPGs with turn-based combat (Undertale), Telltale Games’ franchises as, and, ultimately, longer console games (Okami, Batman Arkham Asylum).