The following is part of Now Loading, a series that renders verdicts on whether or not your favorite video games deserve a place in the canon of works that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. Read the series’ full mission statement here.

There Was a Hole Here…Now It’s Back?

Ladies and gentlemen, orphans of all age and gender, hello and welcome to Now Loading…The Video Game Canon! The only weekly Internet column that takes a look at games from the past to determine whether they should be remembered in the future.

Well, it’s been a long journey through that town, Silent Hill, this past month and change. While we’ve had our emotional ups and downs with the series, it’s time to bring this retrospective to a close. And sure, we may not still be within the spooky month of October, but we are currently celebrating Guy Fawkes day on the Fifth of November, and what could be more frightening than a radical terrorist trying to blow up a government building in a violent display of anarchist rage?

What’s the connection between that and a video game series about people experiencing deep, painful trauma and then dealing with the sins of their past? Well, tenuous at best, Dear Reader, but a man can try, for God’s sake.

Before taking a look at the last game to be overseen by Team Silent, I would like to take you all back to late fall of 2004. I was but a young lad with a twinkle in his eye and a handful of cash in his pocket, and every now and again I would tie up my little shoes, hop on my little bike, and make my way into the town proper so that I could visit the Ol’ Hollywood Video and rent me a game for the weekend. Back then, the aisles of the video rental store looked like looming mountains of possibility, with all the many possible worlds of video games crying out to be played. “Rent me,” a Gamecube game would beg. “Take me home,” said an Xbox title. “We’re worried about you having imaginary conversations with video games and would recommend you spend more time developing interpersonal skills, using them to make friends, and maybe spend less time on the couch and more time experiencing the world around you in the prime of your childhood…” said the PlayStation games.

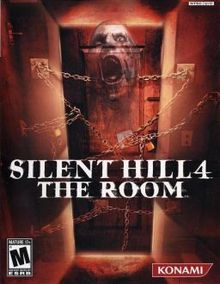

And though I was excited to walk through those aisles and pick out my weekend entertainment, there was always one part of the store that I would try my best to avoid. I was a skittish child, and I knew that if I turned a certain corner in that Hollywood Video, I would be plagued by what I saw for my entire bike ride back home. For you see, Dear Reader, amongst the happy, smiling box art of games like Super Mario Sunshine and Kingdom Hearts lurked a far more sinister face, literally attempting to break the confines of its own box to scream itself into its own hellish existence. That box art, Dear Reader, belonged to Silent Hill 4: The Room, and it is only because that box art scared me so much as a boy that I am now able to wax poetic for so long on the Silent Hill series. Because, like the series itself, the box art for the fourth game was so eerily off-putting and disturbing that it both scared me out of my wits and intrigued me beyond all sensible measure.

While I wasn’t old enough to rent the game from the Ol’ Hollywood Video, I luckily had some friends with rather unscrupulous parents who could be coaxed into renting it, and coax them we did. What followed was an all-night play session that resulted in my being interested in not only the Silent Hill series as a whole, but also in the horror genre quite generally. Without that terrifying face screaming out at me from the shelves of a video store, I would never have delved so deeply into the terrors that warp our minds; I would never have plumbed the depths of human sanity searching for answers to the very questions that would no doubt plunge any man, woman, or beast into the abyss, and certainly would never have devoted an entire month of Now Loading to examining and exalting a series that has laid the groundwork for all survival horror games that followed.

And so, with Silent Hill 4: The Room being not only my entry point into this series but also into horror in general, does it stand the test of time? Has this entire month been leading to my telling you about a game that is so important, so enriching, and so inherently interesting and well-made that it deserves to be remembered alongside the works of Shakespeare, Hemingway, and some funny third thing? Has this introduction finally gone on long enough and gotten to the point where I say that Silent Hill 4: The Room deserves to be in the Video Game Canon?

No.

That is a really scary cover, though.

No, I’m afraid that, even though it’s not as bad as critics made it out to be, Silent Hill 4: The Room just never quite reaches the heights of the other entries into this series. In fact, it’s not just that it doesn’t live up to the other games: it actually falls flat in quite a few places, and its somewhat sloppy execution is indicative of how much Team Silent had begun to lost interest in the series. As I mentioned last week, Silent Hill 3 was released to favorable reviews from both critics and players, but it never quite shined as brightly as the first two entries in the series. And with the survival horror genre exploding with titles like Resident Evil 4 and later entries into the Fatal Frame series, Silent Hill was unfortunately finding itself in the “old hat” category.

The real shame about this, as I see it, is that while Silent Hill 4: The Room is not as well-made as its predecessors, it does offer some new, weird things to the series that unfortunately were too little and too late after the release of the third game. Silent Hill 3 was a direct sequel to the first game, and it seemed that any new entry into the series after that would just be more of the same. Players and critics alike had series fatigue with these games, and when the third game came around and gave the impression that Team Silent was becoming a one-trick pony, there wasn’t much interest to be drummed up for Silent Hill 4: The Room.

Unfortunately, the game just isn’t good enough to prove the critics wrong.

Story and Characters: Henry? Henry Townshend? Well hey, Walter Sullivan! How the Hell Are Ya?

If you’ve been following my work this month on the Silent Hill series, you will recall that the overarching theme of this series is that of the cycle of abuse, and how the abusers and abused alike perpetuate that cycle in a wheel of misery that never quite stops rolling no matter how many good people try to stop it. Silent Hill 1 and Silent Hill 3 both explore this concept through the abhorrent actions of a cult named “The Order,” whose modus operandi essentially revolves around making children suffer infinitely in an attempt to birth an eldritch demon god into the world so that even more suffering can plague our world—the most horrifying, literal representation of abuse possible. And while Silent Hill 2 takes an aspect of that cycle of abuse—namely, guilt—and masterfully explores it, that game manages to tell its own story that eschews the actions of the Cult entirely and instead focuses on the inherent weirdness of this town that acts as a sort of purgatorial space for sinners undergoing intense mental anguish.

Well, Silent Hill 4: The Room tries to follow in the second game’s footsteps by ignoring an aspect of the previous games and exploring something on its own.

Unfortunately, the thing that this Silent Hill game ignores is the town of Silent Hill.

Now please leave!

Now, don’t get me wrong: the town of Silent Hill and its history still play a major role in this game, but instead of the game taking place solely in Silent Hill, the titular “room” in which you’re trapped is actually located in a town called South Ashfield, which we learn over the course of the game is something like a half day’s drive from the town of Silent Hill.

The game still tries to provide the oppressive atmosphere and feeling that you are trapped by the town by having the main character, Henry Townshend, be confined to his apartment room for segments of the game, only to crawl through weird, claustrophobic, interdimensional tunnels to appear in various locations across the town of Silent Hill, but this feels so disjointed and poorly executed that you never really feel trapped in the confines of the town, like you did in the earlier games. This isn’t necessarily the worst thing in the world when it comes to the story that this game in particular is trying to tell, but, when examined against the other entries in the series, this choice to take you out of the town shows that Silent Hill 2 really was a fluke. It’s as if Team Silent were admitting that the idea of a purgatorial town isn’t nearly as interesting as a satanic cult hellbent on summoning a demon into the world.

Just another stumble after the misstep that was Silent Hill 3.

With the issue of the setting out of the way, we can move onto the truly bizzaro-bonkers story Silent Hill 4: The Room has to offer. As with my previous articles in this series, I’m going to break down the basic plot of the story, and then focus on the characters and what they represent. Unlike my previous articles in this series, I’m going to relish just how goddamned weird the story of this game is. So open up your apartment door and call it Mama, we’re diving straight in.

The first thing we need to understand with Silent Hill 4: The Room, is that, like the first game, the story we’re following isn’t actually that of the main characters. While we play as the nearly mute Henry Townshend, the story actually revolves around abandoned-orphan-turned-serial-killer Walter Sullivan and his crazy motives for all his wacko killings.

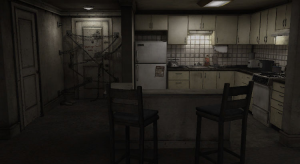

You see, when Walter Sullivan was just a baby, his parents just couldn’t stand him. They hated how he cried, hated how needy he was, and had a general disdain for him that is so cartoonishly evil that Saturday-morning-cartoon villains think it’s a little bit harsh. Their solution to the problem that was their infant child was to simply abandon him in their apartment, Room 302 of South Ashfield Heights apartment complex.

Home sweet home.

This infant abandonment would be tragic enough, but we pile on the sadness when we learn that, due to his abandonment, little baby Walter Sullivan was so traumatized and so intent on finding a mother figure that he assumed that the apartment itself had become his surrogate mother—or, at the very least, a second womb. He became so attached to the room that his entire raison d’etre and motive for committing brutal murders was to somehow return to the apartment, imbue it with some sort of motherly energy, and then live as apartment-mother and son for the rest of eternity.

You with me so far? Because things get weirder.

Enter our avatar and Sears-mannequin-granted-sentience, Henry Townshend. Henry has been living in Room 302 for a little while now, and while the utility costs are pretty low and he likes how close he is to the center of town, he just can’t get beyond the fact that he has been supernaturally locked in the room for the past five days and can’t seem to contact anyone to let him out. That is, of course, until a giant, supernatural portal opens up in his bathroom and, after crawling inside it, he finds himself in a subway station.

These portals open and close a number of times for Henry, and, each time he enters one, he finds himself in another location in Silent Hill, where he encounters a host of wacky characters whom Walter Sullivan kills, one after the other, in an attempt to fulfill an ancient rite known as the “21 Sacraments” to summon The Order’s evil demon god back into the world of the living.

Mondays, am I right, Henry?

You see, after Walter was found as a child living it up on his own in an apartment that he thought was his mother, he was taken to an orphanage called “Wish House” in the far off town of Silent Hill. Unfortunately for Walter, the orphanage was run by a sect of The Order that was tasked with essentially finding and raising children so that they could be lambs to the cult’s slaughter. Effectively, Wish House was trying to pump out more and more kids that could take over for Alessa from the first game in case anything should happen to her, which only adds to The Order’s sadistic need to torture and torment children, no matter what’s going on with the demon god situation.

While he was at Wish House, Walter Sullivan discovered the ritual of the 21 Sacraments, which is essentially a way to summon the demon god into this world without the whole “incubating a child with torture, fear, and hatred until she pops out the Anti-Christ” thing. The book in which the 21 Sacrament ritual is outlined is called “The Crimson Tome,” and refers to the birth of the unholy god into this world as “The Descent of the Holy Mother.”

Being a child, and desperately wanting to return to his apartment mom, young Walter sees this ritual as a way to go back to the way things were when he lived in Room 302. He does this by killing 21 people, each of whom corresponds to a different sacrament, and is stopped at the end of the game when Henry Townshend throws his Walter’s own umbilical cord at the monstrous demon god trying to re-emerge into our world.

The Silent Hill series is strange, but Silent Hill 4: The Room is Looney Tunes.

Looney, I tells ya.

The beautiful thing about these games, and especially this one, is that even if the story itself is pretty insane, the characters are always incredibly well-written and interesting.

Take Walter Sullivan, for example, who, despite coming off as a crazy weirdo with insane motives, is really just another victim of cold-hearted abuse. Silent Hill is really intent on exploring how abuse and cruelty change a person, and Walter is no exception. He’s left to die as a baby, ripped away from his perceived mother, and handed over to a group of insane cultists who, when they’re not torturing or killing children, are grooming them to go out into the world and kill people in rituals intended to bring about the end of days.

He’s an insane killer, yes, but he’s also the product of intense abuse.

We’ve discussed in previous entries that Silent Hill is very intent on exploring the dichotomy of the abused versus the abuser, and that culminates, somewhat lazily, in Walter Sullivan. After the first ten people he kills for the Sacrament ritual, Walter kills himself as the eleventh victim, and is then resurrected through evil magic so that he can keep killing and finish the ritual. During this resurrection, he is split into two versions of himself: The older Walter Sullivan, who is intent on killing and finishing the Sacraments, and a younger, more innocent Walter Sullivan, who just wants all this horror to come to an end. And while I personally think this is a lazy writing tool to represent someone who is of two minds, the game does add quite a bit of nuance to these two characters that first makes you wonder who is the abused and who is the abuser, and then makes you wonder if there’s any real difference between the two in regard to the cycle of abuse that has gone on for decades and generations.

Yes, let us go and be strange elsewhere.

Take the three male victims we see over the course of the game: Jasper Gein, Andrew DeSalvo, and Richard Braintree. All three of these men have some connection to Walter both old and young, and when we see them get killed, there is reason to believe that either version of Walter could have committed the act. Jasper Gein, though clearly suffering from PTSD after having seen Walter kill two of his best friends, is also obsessed with the town’s cult. He says time and time again that he can’t wait for the demon god to be brought back into the world, and while he’s screaming his praise for the God, we saw young Walter Sullivan silently judge him as he stares daggers into his soul. The next time we see Jasper, he’s been lit aflame and sacrificed to the god he so desperately wanted to see.

Whoops!

Likewise, we see Andrew DeSalvo, a fat and desperate looking man, pleading with the young Walter, babbling incoherently about “not knowing what he was doing” and “how they made him do it” as a dead-eyed young Walter looks at him with pure vitriol. We find out through various notes scattered throughout the game that DeSalvo was the one who took Walter from the apartment and beat him mercilessly every day in the Wish House orphanage. The next time we see this sniveling, monstrous coward is when he’s been brutally stabbed to death, lying in a pool of fetid water as he bleeds out.

Finally, and possibly most despicably, we have Richard Braintree. Richard was another tenant in the apartment building, and hated young Walter for hanging around Apartment 302. It is implied that Richard would go as far as beating young Walter for snooping around the apartment complex, and nearly killed him when Walter witnessed what he referred to as “Mr. Braintree skinning someone.” Whether this actually means Walter saw Braintree brutally murder and flay a man, or if the translation of “skin” from Japanese is actually referring to something more in line with beating someone to within an inch of their life, Braintree is an objectively bad man who no doubt left horrid scars on Walter, both physically and mentally. This manifests in the most gruesome scene of the game, wherein Braintree is strapped to a chair in his apartment and electrocuted as Young Walter simply looks out a window, feeling nothing.

Hey, pal, you got a little somethin’…

The two other victims we see are both female, and their murders (or attempted murder, as is the case with Eileen Galvin) are both far more brutal than their male counterparts’. The first woman to die is, coincidentally, the first person we meet in the game, Cynthia Velasquez. We find out over the course of the game that she was something of a flirt with Walter when he would take the subway, and when Walter tried to show some affection towards her she lashed out at him, calling him repulsive and ugly. And while we don’t actually see her get killed, she is brutally beaten and stabbed to a bloody pulp before shuffling off this mortal coil.

AAAAAAAAAAY, I DIE

Eileen Galvin is, with the possible exception of Henry, the only kind person in the entirety of Silent Hill 4: The Room. She is the twentieth sacrament, and is actually left alive because Walter chose her as the new vessel for his demon god mother to inhabit upon her return to this world. He beats her mercilessly, but still chooses her to be the one to live because she was kind to him once. Years and years ago, when Eileen was still a child, she saw a homeless Walter sitting on the steps of the subway station. Saddened by his lonely appearance, she walked over to him and offered him her doll, saying that he looked like he could use a friend more than she could.

This one moment of kindness might have been the only touch of warmth Walter ever received, and so he chose her to be the vessel into which his kind, loving mother would be reborn.

There are other pictures of her, but why would I not use this one?

We come to know Walter Sullivan through his victims, and come to realize that, like many characters in the series before him, Walter is a victim of intense emotional and physical abuse. Unlike those other characters, however, Walter has no qualms about redirecting that abuse outwards towards the world, and will hurt anyone he has to in order to ensure he gets what he wants. He may be sympathetic, but he’s still an evil man hell-bent on violently killing people. That, I think, is where Silent Hill 4: The Room misses the mark.

What the game makes up for in a bonkers story, it suffers in terms of its theming. The theme, once again, is the cycle of abuse, and at this point in Now Loading, we have explored that theme to death. There might have been something poignant to say about the two Walters having both abuser and abused tendencies, but, like my Guy Fawkes reference in the introduction, the connection between those two characters and the exploration of the subtle nuances of abuse is tenuous at best. Walter Sullivan, while an interesting character, just isn’t interesting enough to be a vehicle by which we continue to explore the themes of abuse.

And, regardless, by the time we’ve reached the fourth game enough is enough with abuse already—let’s look into something else.

And before you make the clever argument that perhaps that’s the point, that even the series itself is engaging in some sort of weird version of abuse towards its players, tell your story walking. I see no positive evidence that says the game is that clever or pretentious. That all being said, we’ve covered the bare plot and taken a look at the characters, so I think it’s time to move on.

Gameplay, Visuals, and

Oh! And Henry Townshend, the avatar, is also there. He’s pretty bland, but we’ll talk about him later.

Gameplay, Visuals, and Music: But Wait! There’s Less!

When it comes to the gameplay, visuals, and music in Silent Hill 4: The Room, there’s not much to say that I haven’t already said in previous articles. Essentially, take everything I said about these aspects of the previous games, and then turn down the quality on each by, like, two notches. The game looks a bit worse visually than the third game, and the music feels kind of samey, but it’s still an incredibly striking game from both those perspectives. It does seem like Team Silent was given either less of a budget or far less time to put this game together, though, because after the masterful visuals of Silent Hill 3, there are a few graphical inconsistencies that make this game seem like it came out before the third game.

That’s not really something you want in a sequel, especially after the last one looked so amazing.

There’s one change to the gameplay that, while frustrating, actually adds quite a bit to the survival horror element of the game. There are far fewer ranged weapons in this game, and so you have to run up to the monsters a lot more frequently and risk getting hurt. On top of that, when you want to grab something from your inventory, the game doesn’t actually pause for you. You have to get the items in real time, so there’s a sense of urgency that makes each fight a lot more frightening: you never know if you’ll have enough time to grab a healing item or switch weapons before the monster kills you. It’s a small touch that was fairly ill-received by most players, but, in my opinion, it adds another layer of fear to the combat.

Akira Yamaoka is the composer again, and, again, the music is wonderful. However, where this game fails miserably is in the general sound design. Every single sound, whether it be the opening of a door, the grunts and cries that monsters make, footsteps, animal sounds, you name it, is a stock sound. The sounds in this game seem so generic that I frankly wouldn’t be surprised if the sound designers said, “Forget foley, we’re just going to stocksounds.net. Who cares about ambience, I want that door to creak like every goddamn door you’ve ever heard in a movie.”

This is so glaring an issue that I kept waiting for the Wilhelm scream to pop up in a boss fight.

Impact on Video Gaming and Culture: Good Night, Sweet Prince

Sadly, there’s not much to say here. I mentioned in the last article that Silent Hill 3 marked the beginning of a stagnation period from which the series would never recover, and Silent Hill 4: The Room was the final nail in the quality coffin. This was the last game that Team Silent would work on, and, while Akira Yamaoka would go on to compose the soundtracks for future installments in the series, the games would never have the same feel that these original four did.

It’s a bummer, really, to see a development team you respect go their separate ways and move on to other things, and yet, with the Silent Hill series, it seemed inevitable after the release of the third game. There were already rumblings that the fourth installment would be the last game that Team Silent worked on, and after it was released to a fairly unanimously poor response, it was no wonder that there wasn’t going to be a Silent Hill 5: Birdemic.

Like so many great development teams, Team Silent was comprised of a bunch of rejects from Konami, and when they made the first Silent Hill, they all went into its release assuming it would be the last game they would ever get to work on for the company. Imagine their surprise when, after resigning themselves to failure, their game went on to massive acclaim and helped set the stage for an entire genre. The sequels after the second game were disappointing, sure, but Team Silent was a rare group of creators who were able to make something they truly believed in, and tell one of the weirdest, most haunting, and most influential video-game stories ever to hit a CRT screen. For that, I am nothing but grateful.

Here’s looking at you, Silent Hill!

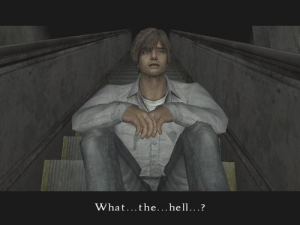

BONUS LEVEL: Oh, Henry

This is both the shortest Bonus Level I will ever write (besides, you know, that other one) and the funniest non-character I will ever have to examine.

Henry Townshend is bland. Oh boy, is he bland. He barely says anything in the game, has the most tepid, neutral reactions to horrific, nightmarish things, and brings shame to the other Silent Hill protagonists. And yet, there is something interesting to say about him!

Just before the final boss fight, it is revealed that Henry is actually the 21st Sacrament that Walter needs before his apartment mom can come back into existence. We find out that Henry represents the “Receiver of Wisdom” Sacrament, and, as such, acts as the witness to the whole story so that the god’s evil can be passed down to generation after generation, and so forth. And while it’s not as interesting as certain other Bonus Levels I’ve written for this series, I do like the idea that the game itself is calling out the avatar for being the player’s window into this story and its world.

And not only that: by writing this series and telling you all about Silent Hill as a whole, I’m also kind of proving the game’s point by passing on the story of this series to new people, thus perpetuating the cycle that keeps popping up all over these games.

Henry Townshend, Mister Bland himself, actually serves as a great storykeeper for the past four games, and, by association, so too does the player. This is by no means a new thing in video games, but, by calling the player out as the “Receiver of Wisdom,” it wraps the whole series up with a nice little bow that essentially says that, by experiencing all four stories that this series has to offer, we, as players and human beings, have grown a little wiser. Hopefully, we will be able to break these horrible cycles, should we ever actually come into contact with them.

So well done, Henry, you corn chip. I doff my cap to you, sir.

VERDICT: Two for Two

While I respect Silent Hill 4: The Room for telling a more wild and out-there story than Silent Hill 3, it just doesn’t live up to the standards that the first two games set for the series. There’s a reason why this was the last game in what many fans consider to be the only four “real” games in the series, and between its bonkers plot, lackluster sound and visual design, and botched exploration of the series’ primary theme, I cannot in good conscience admit this into the Canon, even though it played a large role in my love of survival horror games and the horror genre in general.

Perhaps next October, we can take a look at the other Silent Hill games, but, for now, I would like to salute Team Silent and the brilliant work they did on this series. There were some peaks and valleys, but I’ll be damned if their peaks didn’t provide some of the most introspective and amazing experiences in gaming.

Cheers, Team Silent, and thank you for these stories.

1 Comment

Fitzgerald · October 9, 2020 at 5:45 pm

Thanks for this im a Silent Hill series fan and i really enjoyed reading this.