Regulars of With a Terrible Fate know that, back in the spring of 2013, I undertook a project analyzing the various role-playing dynamics of well-known video games and theatrical pieces. I have been publishing pieces of this study over the past few months on this site, which is the first time they have been published online — I began with an analysis of “Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask” and “Six Characters in Search of an Author” (which you can read here) which I followed with an exploration of the similarities between “Dishonored” and “Macbeth” (which you can read in Parts 1, 2, and 3). Now, I am releasing the third installment of this old study, in which I argue that “Deus Ex” and “Flowers for Algernon” both give us unexpected insights into how we can become better versions of ourselves. My hope is this will be a timely moment for this work, in anticipation of the latest addition to the “Deus Ex” franchise: “Deus Ex: Mankind Divided.”

Note, again, that this older work is not altogether reflective of my current stances on video game theory. It also focuses much more heavily on the phenomenology of games — that is, what it is like to experience playing a particular game — whereas my current work is more focused on the architecture of games as aesthetic objects. Nevertheless, I hope readers will enjoy the piece. Stay tuned, too, for updated work on “Deus Ex” in the weeks to come. It is a series well-deserving of its many accolades.

Treatment IV

The Augmentative Role: Striving to be more than We Are

I had to know. The meaning of my total existence involves knowing the possibilities of my future as well as my past. Where I’m going as well as where I’ve been. Although we know the end of the maze holds death, I see now that the path I choose through the maze makes me what I am. – Charlie Gordon, “Flowers for Algernon”[1]

Synopses

- “Deus Ex: Human Revolution,” Square Enix

“Deus Ex: Human Revolution” poses a question hauntingly relevant in our modern society: ought humans to implement biotechnology to take control of their own evolutionary development? The game is set in a near-future world where biomedical corporations have taken the lead in the new market of human augmentation: the enhancement of humans by implanting technology which allows them to “unlock the hidden capacity of our DNA,” ranging anywhere from increased physical strength to enhanced social skills. The central conflict asks the question of how society will move forward with this newfound ability to “play God,” with “purist” organizations and extremist factions standing in opposition to biomedical companies and their patrons.

The player assumes the role of Adam Jensen, the head of security for Detroit-based leading biomedical corporation, Sarif Industries. On the eve of a planned meeting between the company and the U.N., at which the company planned to present their most recent findings and argue against the need for augmentation regulations, an unknown group attacked the company; their leading research team, headed by Dr. Megan Reed, was killed. Adam was brutalized in the attack, and was subsequently heavily augmented by David Sarif (the company CEO) so that he might survive. He then embarks on a mission across the city and globe to uncover the truth behind the attack, and finds a far greater conspiracy than he ever imagined. He learns that the attack was orchestrated by a number of high-powered cogs in a much larger machine: the Illuminati, seeking to exploit augmentation implants to exert control over all augmented people from the inside. They staged the scientists’ deaths and kidnaped them in order to develop a biochip that they could distribute under the pretense of a software update, thereby literally enabling mind control over vast populations. Hugh Darrow, the father of augmentation technology, having discovered this, broadcasts his own signal to the chips, inducing acute psychosis in all augs (i.e., ‘augmented people’) in an effort to “put the genie [of augmentation technology] back in the bottle” by making mankind privy to its dangers through example. Adam is left with the task of disarming the signal and deciding what message to broadcast around the world explaining what happened. He has the options of: blaming the signal on purist group “The Humanity Front”; blaming it on a biomedical error; telling them the truth of what happened; or destroying the entire broadcasting facility, letting the truth die with it.[2] In so doing, Jensen is made to choose the future trajectory of humanity in regards to its perception of augmentation. After a journey in each Jensen has seen every way augmentation has affected the world, the player is given the onus of choosing how mankind might best proceed.

- “Flowers for Algernon,” David Rogers, based on the novel of the same name by Daniel Keyes

“Flowers for Algernon” tells the story of Charlie Gordon, a mentally disabled thirty-two-year-old, whose teacher volunteers him for an experimental intelligence-amplifying operation, which enables him to learn and retain information at an exponentially higher rate. Charlie steps out of the shell of his disability and sees the world first as others see it, and eventually in a far more integrated, enlightened way than any of them can perceive it. Yet his emotional development is unable to keep pace with his intellectual development, as he is tormented by his past, the way he can now see how little respect he was given when he was mentally disabled, and his inability to relate to those of lesser intelligence than he.

Eventually, Charlie learns that there was a flaw in the original research (a flaw which, ironically, could not be perceived except by his enhanced intellect), and that he will eventually lose his intelligence until he is back where he began. In so learning, he is put in a position where he must live the entirety of his life as intelligently conceived in the space of a few short months of research – and learning to love. Charlie’s tragic story speaks to the question of who we truly are, who we might become, and how we change by virtue of the journey.

- Role Playing in Psychotherapy, Raymond J. Corsini

In this slim volume, Corsini deftly outlines role-playing’s role as a pragmatic, aggressively effective tool in the psychotherapist’s arsenal. He describes its threefold usefulness for purposes of diagnosis, teaching, and training. Of particular interest to us are his theories of role playing’s use in ‘training’: he argues that a patient, directed by the psychoanalyst, can effectively change his behavior through role playing sessions – and, subsequently, can change his perception of himself (what Corsini refers to as the patient’s ‘self-concept’). This idea of self-transformation through an external enabler is similar to the dynamics of both Charlie and Adam’s growth; therefore, it is a useful template through which we can understand role-playing in both of these stories.

Introduction: “Without control, there’s no room for freedom”

A canonical philosophical question is whether free will exists. Do we, as humans, possess the capacity to genuinely choose? Or are our decisions, along with everything else ever to occur, predetermined by some metaphysical god? Or, is choice illusory by virtue of our behavior being conditioned by external stimuli and subsequent reward pathways? Complex, involved arguments exist for virtually every side of this debate, and we will not presume in this piece to offer any substantive framework for answering this question; rather, the question of free will serves as our jumping-off point for a central issue of this study: how do the measures one takes to define oneself relate to external influences?

B. F. Skinner believed that behavior was a function of external conditioning and reward, what he referred as ‘operant conditioning’. In his world, everyone’s behavior (or ‘will’) is a product of the feedback their actions yield from the environment upon which they are performed. Skinner’s world is not necessarily one of strict determinism – rather, environments establish behavioral patterns by greatly increasing the probability of individuals electing to act in certain ways that yield desirable results. Thus, the individual still acts “as he wishes” – the environment simply influences how he wishes to act.

A behaviorist paradigm such as Skinner’s is not far-removed from questions of role assumption, particularly where theater is concerned. Consider the director-actor relationship: the actor is responsible for bringing the reality of the play to life, and it is his choices and actions onstage which effect this; yet these choices are heavily informed by the vision and directions of the director. So the word of a theatrical play might be roughly generalized as ‘a distinct but not discrete reality with an onstage locus of choice (i.e., the actors) and offstage locus of control (i.e., the director)’. To continue the Skinnerian analogy, the director serves as the environment by which the actors onstage – and, consequently, the collective and personal realities of the play – are conditioned.[3]

By considering this dynamic, we are beginning to flesh out a fourth version of the meta-role: what we will call the augmentative role paradigm. It is this paradigm that provides a distinct mechanism for a change in self. When Adam reaches Hugh Darrow’s Arctic hideaway, ‘Panchaea’, he finds Humanity Front leader William Taggart holed up in a server room, hiding from the crazed augs. In trying to convince Adam to blame the catastrophe on biomedical corporations to compel strong industry oversight, Taggart warns Adam that, “without control, there’s no room for freedom – only anarchy.” The augmentative meta-role paradigm offers insight into people at their most dynamically transformative, but with a crucial caveat: this transformative capacity is externally potentiated.

“Hybrid life support”: a sketch of the evolutionary self

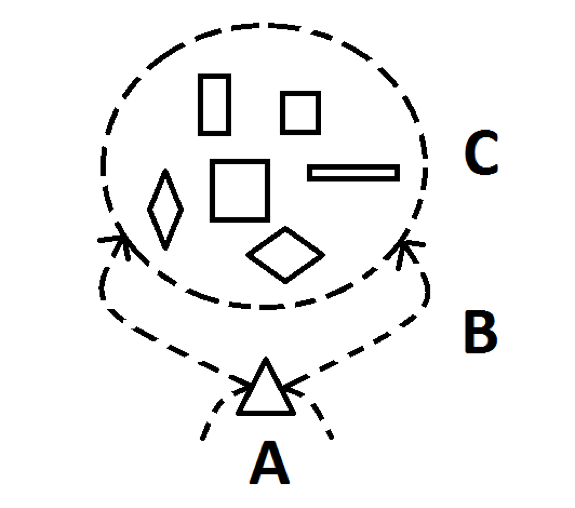

To better understand the augmentative paradigm at work, we will break it into a multi-component model, and assess the way in which the components work together to facilitate self-evolution. We can graphically represent the model as follows.

We can formally define the paradigm in this way: the augmentative meta-role paradigm describes the transformation of a base role (‘A’, the triangle) into the base role’s choice of any number of variant roles (‘C’, the set of possible shapes) by virtue of an internal evolution of A made possible by an external evolving agent (‘B’, the arrows transforming A into a member of set C). In our standard meta-role terminology, the base role is the primary role, and the variant role is the secondary role.

There are two distinct-but-similar mechanisms by which the augmentative meta-role paradigm is actuated in “Deus Ex” and “Algernon”: in the former, the mechanism is human augmentation; in the latter, it is intelligence enhancement through neurosurgery. Both are effected by an external party: Adam is mortally wounded and in no position to choose whether or not he wants to be augmented, so Sarif makes the decision for him; Charlie is not intelligent enough to actually understand the implications of what is going to happen to him through the operation, merely saying that he wants to be smart like everyone else so he won’t be lonely, and so the choice is largely left to his teacher and the scientists.[4] In both cases, the base role is enabled through the external evolving agent to develop in a multifarious way: Adam is given license to activate any of the implanted augmentations he desires to evolve himself however he sees fit; Charlie, having been given the enhanced capacity to learn, may absorb whatever information he likes and administer his newfound knowledge in whatever ways he sees fit – ultimately doing so in the tragic irony of scientifically proving that he will lose his newfound intellect. Given the similarity of these two cases, we will examine the finer points of the augmentative meta-role paradigm’s dynamics in the case of each subject, and then synthesize a more general conception of the ways in which the paradigm functions.

Deus ex machina: stealing fire from the gods

How would the gears in the modern political machine respond to the potentials of human-controlled evolution? Square Enix explores that question by presenting a debate set in the home of democratic discourse (The United States of America, Detroit), as well as on a global corporate scale. As one might expect, people’s opinions are immediately polarized between those who want to move forward in human development through augmentation – biomedical corporations and augs – and those who vehemently decry human augmentations as a crude distortion of the natural order of life – lobbying groups such as the Humanity Front, and extremist factions such as Purity First. Each side is represented by a leader who conveys their group’s opinion on humanity: David Sarif, Adam’s boss and head of Sarif Industries, is a progressive aug who is seeking to drive humanity forward with unrestricted human augmentation development; William Taggart, psychologist and de facto leader of the Humanity Front, is seeking to effect rigid restrictions on human augmentation through either U.N. oversight or under-the-table support of the Illuminati bid for more authoritarian control over augmentations; Zeke Sanders is an ex-marine who was augmented to replace an eye lost in war, but, after an incident of augmentation-induced psychosis, tore out his augmentation himself and founded militant anti-augmentation group Purity First as a more direct way of opposing the advancing wave of augmentation. In the midst of all this stands Adam Jensen, the effective interloper between opposing factions.

Adam’s mobility between augmentation factions is stark, and is the main vehicle that justifies the choice placed before him at the game’s end. Adam is the ultimate symbol of augmentation in several ways: he was born as part of a genetic engineering experiment, and it was his extremely resilient DNA which enabled the technology supporting human augmentation to be developed and brought into the mainstream; his own augmentation was chosen by Sarif in Adam’s time of dying. As Adam reiterates several times throughout the game, he “didn’t ask” to be augmented – in point of fact, one private investigator who spent time investigating Adam later tells him that Adam was effectively brought back to life by augmentation. He refers to Adam’s body as a “metal corpse,” calls him a “robot,” and says that Sarif “butchered [him]” by making him a “weapon.” Adam is an interloper by virtue of the fact that on the one hand, he is under the employ of a biomedical industry, yet on the other hand, as his pilot, Malik, says has “every reason to hate augmentations” because of the way in which they were forced upon him. Thus, he has reason to sit in either the pro-augmentation or anti-augmentation group. He may also move between moderate and extremist camps insofar as he is part of the “legitimate business” sector in serving as head of Sarif Industries security, but is also granted extreme leeway in how he goes about getting things done. He may just as easily kill a mob leader in cold blood and stage it to look like a suicide, or plant drugs in the leader’s apartment and let the proper authorities neutralize him.

It is interesting to note the ways in which the game’s avatar mechanics mirror these thematic elements. Drawing from the terms explored at the start of our third treatment, we can describe “Deus Ex” as a first-person, active-avatar game. We noted in our initial definition of these terms that such a setup is an exception to the trend of games being designed either as silent-avatar first-person or active-avatar third-person, and are now in a position to explore how such an exception uniquely defines Adam as an avatar.

Adam is a character compelled to face certain situations based upon external factors – his forced augmentation, his job, the genetic experimentation upon him, and so forth. Adam earns his name by being analogous to the first man: as that Adam was God’s experiment and the root of humanity, so too is our Adam an experiment, the heart of man’s exploration into a new, biomechanical identity. This experimental origin presents Adam with a unique matrix of choices made available to him by parties external to him, but for which choices the locus of control is internal. The actual game dynamics present a strikingly similar situation: Adam is a character with a degree of independence from the player – there are actual scripted, movie-like cutscenes in the game wherein Adam is seen acting from a third-person perspective – yet his path may be directed by the player through choices of directions to take in conversations with NPC’s, methods of completing assignments (e.g., the above-mentioned mob boss), and, of course, the ultimate decision as to how to end the game. In this way, the game recapitulates Adam’s own creation by providing players with certain dimensions of a character, which they may then direct along any path they choose. The methodology of the augmentative meta-role is thereby built into the very fabric of Adam’s reality.

But what choices in particular do Adam’s augmentations, for which he did not ask, allow him do make? The most direct answer is that they enable him to explore his development in far greater depth in whatever area of growth he wishes to pursue. As we have already noted, Sarif went above and beyond the call of duty in outfitting Adam with the latest augmentations after his attack: when he first visits a LIMB clinic, one of the sites set up to perform augmentation surgeries and services augs, he is informed that his implants were designed to activate naturally over time to avoid traumatic after-shock, but that Sarif also made arrangements for Adam to be able to “turn them on manually” over time as he sees fit via Praxis kits, tools available for purchase at clinics or discovery in various places around the world. This leaves it at the player’s discretion to activate and upgrade the augmentations most suitable to his own playing style. The choices of how to proceed is broad: there are cerebral augmentations such as enhanced hacking capabilities; physical augmentations increase such things as stamina for running and armor resilience for greater health; aesthetical augmentations are as wild as dermal armor which refracts light so as to make Adam invisible; and there are such miscellaneous augmentations as the “Icarus landing system,” which allows Adam to fall from any height and land safely, stunning adversaries on his way down. Of course, a player could hypothetically acquire enough Praxis kits to activate and fully upgrade all augmentations (a time-consuming and taxing undertaking), and they would in theory all activate naturally over time; nonetheless, the immediacy of Adam’s quest at hand necessitates a measure of personal choice, meaning that our theory of internally-localized developmental choice still holds. (We can easily see by virtue of a more general example how this logic holds: given enough time, a human could no doubt become a master in every field they could possibly pursue; however, within the confines of the human lifespan, this is infeasible, and so the human must make choices as to which developmental paths they wish to take.) Within this framework, the player is able to explore the game in unique ways based on his own inclinations: if he is aggressive, then he might augment Adam’s health and inventory for as much ammunition as possible and run headfirst into the fray; if he is predisposed towards stealth, he may make Adam invisible and render his footsteps silent even while sprinting, so as to easily slip fast the most heavily-guarded areas.

It is easy to see how such potential advancement gives Adam an enormous advantage over virtually everyone else (even those who are augmented, because they typically only have one or two augmentations due to how expensive they are, whereas Adam has the works – to the point, as previously mentioned, where the P.I. refers to him derisively as a “robot”); yet we can go further and see the sheer magnitude of this advantage by examining one particular augmentation, which we will see is somewhat analogous to Charlie’s situation in “Algernon.” The Computer Assisted Social Interaction Enhancer, or CASIE, is a social enhancement augmentation that allows Adam to chemically analyze people with whom he is conversing, and, at the right moment, release appropriate pheromones (alpha, beta, or omega pheromones) to persuade them to do what he wants. Such an augmentation can be used to extract information from targets, talk someone out of suicide, and convince people to pay him for missions upfront, among other things. With it, Adam is able to easily convince adept psychologist Taggart to give up the location of his aid when it becomes clear that the aid is implicated in the Illuminati conspiracy; with it, Adam is able to convince Darrow to give up the code to shut down Panchaea’s security system by pointing out the fact that the father of augmentation uses a cane – an indicator that he himself was incompatible with the technology, and is partly motivated by bitterness about that. In fact, the only people Adam cannot convince using this software are Malik, who may be similarly augmented, and a rogue private security operative named Zelazny, who was outfitted with similar high-functioning augmentations by the company for which he once worked, Belltower. If Adam tries to use this method to persuade him to turn himself in, Zelazny responds by telling him “It’s a cute little toy you have there, Jensen. But don’t waste your time. Your CASIE won’t work on me.” Malik calls him out on using his software in a similar way. It seems, then, that Adam is only matched in his ability through augmentation by those who are similarly augmented – a fact strongly supportive of the notion that the external augmentative forces exerted upon Adam have literally enabled him to evolve to a point where the rest of humanity is, in a certain way, less able than he is.

This is certainly a significant degree of change, but the game goes further to justify the title’s allusion to the notion of deus ex machina, literally a “god from the machine.” When Adam finds Darrow at Panchaea in the midst of all the chaos he has wrought, Darrow decries humanity by saying that “People believed we should steal fire from the gods and redesign human nature.” These words at first glance seem a bit strong for what we have considered; but Darrow, as the father of this technology, knows the extent of how far it can go, from whence he derives much of his Oppenheimer-esque regret for his own proverbial atom bomb. Darrow understands the depths of his technology’s implications because he has realized its potential in the depths of Panchaea: his fortress’s security system is the deus ex machina of human augmentation.

What is the ultimate formula for a system of control? Such a system much have the knowledge-set of a computer, handling copious amounts of data at once to the point of omnipresence, along with the versatility and creativity of response afforded by the human mind. This is what Darrow has achieved in his stronghold’s security system: when Adam reaches the broadcast center, he finds a room containing an enormous machine – the central hub of the security system. In the center of the room is a column connecting three stasis chrysalides to the machine. Within each pod is a heavily augmented girl bonded to the machine via a “hybrid life support” system. The battle begins when Zhao, a biomedical company’s CEO and the last known surviving Illuminati conspirator, desperately hooks herself up to the system in a bid for control over the broadcasting beacon and all the people receiving it. It is haunting to listen to what the girls are saying during this encounter: before Zhao connects herself, they make such exclamations as the following.

“Who am I?”

“I feel cold.”

“I don’t remember.”

“Oh God, please help me, I’m scared.”

Zhao connects herself, trying to assume a god-like role as the ultimate god-from-the-machine, and the girls respond.

“So much pain.”

*Visceral scream*

“Shut this thing off!”

[Yet soon, as the battle proceeds, their responses change in kind.]

“No! Protect mother! Stay away!”

“Why does he want to kill us?”

“Kill him.”

“No more pain! Please. Keep him away from us!”

“SHOW US THE LIGHT, MOTHER. WHERE IS THE LIGHT?”

“Vital signs… normal? No, this is not normal.”

To defeat the system, Adam must first kill the external, mechanical defense turrets, then open the pods, kill each of the girls in turn, and finally strike Zhao herself, elevated and bound by mechanical chords in a disturbingly Christ-like fashion to the system. But what is the nature of the system itself?

The girls provide the answer to this question. At no moment do they come off as malicious, vindictive, or sadistic – in fact, they radiate innocence, which is perhaps why Darrow comes off as guilty when warning Adam about the defense system that “thinks for itself,” and telling him how to shut it down. The girls seem afraid, having lost their identity in the overarching sentience of the machine. They directly express their desire for the machine to be shut off because of the pain it is causing them; yet a shift soon occurs when Zhao connects and they imprint upon her as their mother. This emotional dimension to the machine allows them to bond with Zhao in opposition to Adam, their aggressor. Yet Zhao proves inadequate as a mother figure, because she seeks to manipulate the machine for her own egoistic benefits, and has no desire to protect or foster its human element; thus the girls are not relieved of their suffering in any way, and helplessly ask their “mother” “where [the light is].” Thus, the very humanity which renders the machine a god also renders it imperfect: its mechanical aspect robs its human component of identity, and Zhao is unwilling to appease the human aspect because she is using the system as she would any other machine, seeing herself as the only human interface. When she is finally bested, she is literally incinerated by the energy of the system coursing through her body, proving her own being inadequate for the system. In this way, the methodology of augmentation taken to its extreme, wherein the difference between human and machine is inscrutable, is shown to be a truly terrifying force: the system is self-contained and terribly powerful in that it destroys Zhao, but also deeply pained and scared in its human sense of lacking identity. It craves fulfillment that cannot be humanly found because someone who could serve a human role, like Zhao, is insufficient because the system’s machine qualities interface with her before its human qualities ever can.

We see, too, in the story’s periphery, the plights of those less fortunate than Adam, whose bodies reject augmentation implants in a potentially lethal reaction, who are then forced to rely for the rest of their lives upon a drug called ‘neuropozyne’ to stave off rejection symptoms. In much the same way that drug addicts turn to crime and underground operations to get a fix, these people often deal for neuropozyne in the dark because of its price tag. We also saw the way in which Zeke Zanders violently rejected augmentation after his own induced psychosis, at which point he attempted “suicide by cop” before William Taggart talked him down. Considering this in conjunction with Darrow’s security system, we see the augmentative methodology presented in “Deus Ex” as bookended by two horrifying extremes: on one side, visceral rejection of augmentation, threatening the subject’s life and sanity; on the other, perfect fusion with the machine, destroying the subject’s humanity by irreparably handicapping their capacity to relate to their own human qualities, or the humanity of others. We must also not forget that even those augs who are happily in the middle of this spectrum were susceptible to the madness invoked by Darrow’s mind-controlling signal. Adam, then, appears to sit in the perfect balance of an augmentative paradigm which, under certain circumstances, can be wildly evolutionary, but, in many other circumstances, can destroy one’s very fabric of being from the inside out.

The Other Charlie: “I can’t help feeling that I’m not me”

If we could enhance the intellect of the mentally handicapped to genius levels, ought we to do so? This is the exposition at the heart of “Flowers for Algernon,” where a man not intelligent enough to understand the world around him is thrust headfirst into it by an operation designed to revolutionize I.Q.

The crucial distinction between the evolutionary potentiation of Charlie and Adam is that whereas Adam, essentially dead, was not in a position to choose what became of him at all, Charlie was fully conscious, rendered naïve by virtue of his mental deficiency. As mentioned earlier, Charlie is aware and eager of the opportunity to become smarter through the surgery, but in an innocent way that does not grasp the implications of what would actually happen to him. Charlie clarifies this after the operation, when he is confused as to the lack of immediate change within him, and Dr. Strauss tries to explain to him how the operation worked.

Charlie: Am I smart?

Strauss: That’s not the way it works. It comes slowly and you have to work very hard to get smart.

Charlie: Then whut did I need the operation for?

Strauss: So that when you learn something, it sticks with you. Not the way it was before.

Charlie (disappointed): Oh. I thought I’d be smart right away so I could go back an’ show my frien’s at the bakery… an’ talk smart things with ‘em… like how the president makes dumb mistakes an’ all… If you’re smart, you have lotsa frien’s to talk to an’ you never get lonely by yourself all the time.[5]

Charlie, then, is in a position to “consent” to his evolutionary potentiation, but not from a competent mindset – such a mindset would only emerge after his intelligence was enhanced. The choice he made, therefore, while certainly a real one, could only be understood by him on an integrated level after he shifted (to use augmentative role terminology) from a state of base role to actuated role. After this brief state of enlightenment, he returns to his original state of intellect, and the integrated conception of his change again eludes him – we see that Charlie’s final progress report reflects this lack of understanding.

I did a dumb thing today. I fergot I wasn’ in Miss Kinnian’s class any more. So I went and sat in my old seat… an’ she looked at me funny… an’ I said, “Hello, Miss Kinnian. I’m ready fer the lesson on’y I lost the book we was usin’”… an’ Miss Kinnian… she start in to cry – isn’ that funny? – an’ ran out. Then I remember I was operationed an’ I got smart… an’ I said, Holy smoke, I pulled a real Charlie Gordon.[6]

In Charlie’s ultimate regression to his base role state, he forgets about the relationship he established with his teacher, Alice Kinnian, at his intellectual peak, reverting to his original submissive-student relationship to her. He reverts to his original simplified conception of how his intelligence-operation was meant to work, and his own conception of himself as mentally challenged, for which his cruel coworkers termed doing something stupid “pulling a Charlie Gordon.”[7] The case of Charlie Gordon illustrates an important point: one undergoing the evolutionary process of the augmentative role paradigm cannot comprehensively conceive of the evolutionary path connecting base role to variant role, unless one is currently operating as a variant role. This point was not as apparent in “Deus Ex” because Adam never “regressed” from being augmented, but we could presume it to be equally true – after all, it would have been virtually impossible for Adam to have conceived of such abilities as the CASIE without having first experienced it, thereby being in a state of variant role.

Such an isolation of understanding between base role and variant role suggests a stark stratification of self – one at which we have already hinted by means of our evolution-based terminology, but which “Algernon” explicates in even greater detail. The further Charlie evolves, and the closer he draws to his inevitable return to his mentally impaired state, the more he is haunted by the image of himself as a teenager, whom he calls “the other Charlie.”[8] This ‘other Charlie’ appears before Charlie as the psychical representation of who he once was, brought into more dramatic relief by Charlie’s increasing memory of his traumatic childhood experiences, growing up with a family who dealt terribly with his condition. In the throes of his increasing emotional instability, he explains this situation in vivid detail to Alice. The scene begins by his landlady coming to check in on him, mentioning how she saw him the previous night fumbling outside his apartment, behaving “like he was a little boy,” which we recognize as his reenactment of his childhood. Alice, upon hearing this, asks if this is why Charlie called her after ignoring her for a long time.

Charlie: I called because I wanted to see you. I didn’t remember… that. But I’m not surprised. He wants to get out. The other Charlie wants to get out.

Alice: Don’t talk like that.

Charlie: It’s true. He’s watching me. Ever since that night at the concert. That’s why I couldn’t see you. I was afraid of seeing him.

Alice: That isn’t real, Charlie. You’ve built it up in your mind.

Charlie: I can’t help feeling I’m not me. I’ve usurped his place and locked him out… the way they locked me out of the bakery. What I mean is, that Charlie exists in the past, but the past is real… so he exists… It’s Charlie, the little boy who’s afraid of women because of things his mother did to him, that comes between us.[9]

The separation of Charlie across two forms underscores the incompatibility of the base role (Charlie pre-operation and post-regression) with the variant role (Charlie post-operation, pre-regression). The difference between the two is not one of circumstance, but rather one of fundamental quality.

Beyond Charlie’s personal turmoil, he provides us with insight into the the augmentative meta-role paradigm’s dynamics in his world: his “life’s work” is a scientific paper on exactly this, which he names the “Algernon-Gordon Effect,” after himself and the mouse, Algernon, who was part of the same experiment and who serves as Charlie’s mirror image throughout his developmental journey. The hypothesis of the paper is as follows: “artificially induced intelligence deteriorates at a rate of time directly proportional to the quantity of the increase.”[10] This hypothesis explains why mice whose intelligence was simply made average through experimentation maintained that intellect throughout their lifespan, whereas Charlie and Algernon had no such hope.[11] The report itself is never explicated, but we may posit several ideas as to how this hypothesis comes to be. Perhaps the most likely explanation is the fact that such artificially induced intelligence actually impairs the subject by virtue of its not being accompanied with comparable emotional growth. Strauss explains this situation to Charlie in therapy when Charlie intimates to him that he no longer finds any joy in working at the bakery, which was his job prior to the operation.

Charlie: …why don’t I enjoy working there anymore, Doctor?

Strauss: Why? You tell me.

Charlie: … They ignore me… No, it’s more. Joe, Frank, they’re… hostile to me. I thought they’d be happy for me [about my intelligence]. They’re supposed to be my friends. It takes the pleasure out of all of this. Why?

Strauss: The more intelligent you become, the more problems you’ll have.

Charlie: Why didn’t you tell me that before the operation?

Strauss: Would you have understood? (Charlie doesn’t answer.) Your intellectual growth is going to outstrip your emotional growth, so, there will be problems. That’s why I’m here.[12]

Such raw intellect without the social skill to handle it with others or emotional skill to handle it within himself marks Charlie as a pariah in the bakery, renders any real human relationship viciously difficult, and leads him to be haunted by “the other Charlie” seeking his body’s return to him. Contrary to the image of Adam as one who can only be enhanced through augmentation, Charlie’s evolution also seems to serve as his Achilles’ heel by rendering his unenhanced dimensions inadequate to his new life.

Another possible explanation for the Algernon-Gordon effect is the sheer influx of information assimilated as a result of operation. The operation only makes Charlie “smart” insofar as it allows him to retain all the information with which he is presented. This is exemplified by one instance in which he read War and Peace in a single night.[13] Such an enhanced capacity suggests an almost inevitable overload: particularly given the inequity of overall development, as described above, it seems highly unlikely that a partly-enhanced subject would be able to sustain so dramatic a transformation permanently.

“Algernon,” we see, also defines an evolutionary capacity within certain bounds, though these bounds are somewhat different from those defined in “Deus Ex.” Whereas “Deus Ex” defined augmentative success as a spetrum of human-machine relationship between total rejection and total fusion, “Algernon” defines it as successful within moderation: that any true qualitative evolution, in the absence evolving the subject holistically, is fated to decay over time. Thus, while both suggest augmentative moderation as the key to success, the former suggests it within a framework of the base role’s level of association with the evolving agent (i.e., the human/machine relationship), whereas the latter suggests it within a framework of level of difference between the base role and resultant variant role. The overarching theme seems to be that the augmentative paradigm is most effective when moderate changes are made between the base role and variant role – so, to return to our graphical representation of the paradigm, a moderate change, such as changing a triangle into a quadrilateral, would be the most viable sort of augmentation.

Synthesis: Pragmatic Evolution

Considering the somewhat bleak admonitions of our subjects in this treatment, it might be refreshing to step back for a moment and immerse ourselves instead in a positive, realistic application of this very role-playing paradigm: the implementation of role playing in psychotherapy.

In his book on the subject, Corsini advocates for the therapist’s use of role-playing in a myriad of circumstances: in individual therapy or group therapy, for the purpose of either diagnosing the patient, teaching the patient by allowing them to observe a role-played scenario, or training the patient to alter behavior and self-perception through role-playing exercises. Corsini has useful insights on all of these means of therapeutically employing role-playing, but we will only examining its use in individual therapy for the purpose of training; we limit ourselves to this lens because, as we shall see, this particular use of role-playing perfectly mirrors our established augmentative framework, while shedding new light on some of its finer points.

Corsini defines role-playing in a psychotherapeutic training context as “a process of making inner gains, in insight and empathy, generalizations and motivations, self-confidence and peace of soul, and all of the usual subjective states of ‘mind,’ through peripheral, i.e., actional processes.”[14] The understanding is that there is a two-way street between one’s behavior and one’s self-concept, Corsini’s term for the “kind of superordinate conception of self which enable the individual to function harmoniously and predictably.”[15] He sees role-playing as an ideal psychotherapeutic tool because “the therapist and assistants can manipulate the situation to create a peak type of experience in which considerable emotionalism will be displayed. This ‘breaking of the log jam’ is invariably followed by insights and usually by feelings of comfort and behavioral changes.”[16] He supports his methodology by such examples as a small boy (‘George’) in a delinquent school, constantly beaten up, who was given a safe space in psychotherapeutic role-playing group to act intimidating and have everyone else be terrified of him. He began raining (pretend) blows upon them, and afterwards – outside of therapy – was more self-assertive to the point where he was no longer beaten up.[17] “[George’s] assumption in therapy of a role,” writes, Corsini, “though it only lasted ten minutes, that was contradictory to his self-concept, must have so shaken his self-concept that it changed into the notion: I don’t have to be afraid of others. It didn’t matter that what actually occurred in the therapy room was only play-acting. It was a veridical experience for George who grasped a new concept of himself, and changed the structure of all his thinking and behaving as a result of this one concept.”[18]

We have here a situation wherein a person’s actual conception of self is changed through an artificial-yet-veridical role-playing environment, orchestrated by a therapist serving as a “director,”[19] with the intent of making inner gains through actions which can generalize to overall observations of self. If there is any doubt remaining as to whether or not the augmentative paradigm is at work, we need only consider the therapist who directs the role playing: as Corsini says, “on the one hand [the patient] generally admires and trusts the therapist, and tends to get in a dependent relationship to various degrees; but on the other hand he resents the manipulation that the therapist engages in.”[20] This is the exact description we would expect of an external evolutionary agent, who must guide the developmental process of his subject in a way the subject cannot understand until he has evolved – the subject naturally trusts the agent’s judgment, because it is that capacity of the agent to change the subject for the better for which the subject first approached the agent for therapy; yet resentment must also linger to a degree based on the fact that the methods employed by the agents necessarily go “over the subject’s head” to some degree. We saw this resentment present in the cases of Adam and Charlie as well.

Corsini’s examples suggest that role-playing as training in psychotherapy can truly do patients good by shaking the foundation of their self-concept and liberating them from old patterns of behavior – changing their understanding of “self,” that is, in a shockingly abrupt manner. Such change, of course, cannot occur in such a way that a single session of role-playing therapy would be sufficient. Corsini gives a fitting example of this in the patient who had difficulty communicating with friends, strangers, and authority figures in situations of trivia, conflict, or where he wants something. This problem was confronted by role-playing all nine combinations of person with whom he is interacting and type of conversation being had.[21] Such a comprehensive ironing-out of every facet of behavior in order to evolve one’s self-concept seems to be in direct response to the issues of incomplete evolution by augmentation raised in “Algernon.” The issue of the base role’s relationship to the evolving agent is not directly addressed, but is opaquely resolved in the considerations of the immediacy of change effected by this role-playing device. Thus, it seems less likely that the subject would develop either a particularly dependent or adverse relationship to the tool itself, because the length of time needed for it to be effective can be as small as a handful of minutes. This, of course, does not negate the fact that role-playing will be more useful in some situations than others; nonetheless, it provides a positive, pragmatic context for consideration of how the augmentative meta-role paradigm might be beneficially implemented.

It is clear in light of this that the augmentative role paradigm can empower a subject by allowing them to determine their own self-concept. Though the paradigm is effected by an external body, that external body in this case serves only to empower the subject to change and evolve himself as he wishes. One might say that therapists are able to mold their patients as they see fit; but, ethically speaking, they may only work to change the patients in the way that the patients wish to see themselves change. So it was with Adam and Sarif, and so did it glaringly fail to be with Charlie. The augmentative meta-role paradigm, misused, can undoubtedly throw its subject into a state of internal disarray, which is why the onus on the evolving agent to enable the base role’s growth into variation in a balanced manner is so great; yet, properly implemented, this may be the most progressive meta-role paradigm yet conceived. As Sarif asks Adam pointedly before the final confrontation at Panchaea, “Would you have been able to do any of the things you did without augmentations?”

[1] “Flowers for Algernon,” Act II.

[2] The four endings vary slightly depending upon whether the player has played through making virtuous choices, malicious choices, or neutral choices; but this variance is much more subtle than that of “Dishonored,” and the primary distinction of endings is the breakdown of four choices enumerated here.

[3] We cannot ignore that the audience’s responses also serve to condition the actors – something considered in Appendix B. For now, as we are concerned with the initial formation of the reality, we are necessarily operating within a pre-audience production context, and therefore will not consider them.

[4] “Algernon,” Act I.

[5] Ibid, Act I.

[6] Ibid, Act II.

[7] Ibid, Act I.

[8] Ibid, Act II.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, Act I.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Role Playing in Psychotherapy, p. 91.

[15] Ibid, p. 21.

[16] Ibid, p. 102-103.

[17] Ibid, p. 22-24.

[18] Ibid, p. 24-25.

[19] Ibid, p. 41. Corsini’s treatment of the psychotherapist as a director draws a direct, completely appropriate parallel to the stage.

[20] Ibid, p. 92-93.

[21] Ibid, p. 95-102.