The following is a chapter in “A Comprehensive Theory of EarthBound,” a series that aims to better understand the storytelling of Shigesato Itoi’s landmark video game. Find the full series here.

“That which you most need will be found where you least want to look.” [1]

It is hard not to see EarthBound through the eyes of your inner child. Its candy-rich, saturated color schemes, its vast sense of scale, the way it heroizes the act of picking up a baseball bat and heading out to make some friends; all these things near enough oblige that the gamer set down their mature jadedness and pick up a pair of childish lenses they may not have put on for some time. To bring a player so unilaterally into a world by virtue of robust characterization and distinctive design, as EarthBound does, is a mark of mastery.

The mastery of EarthBound’s characterization is fairly often remarked upon; as with many other games, its setting seems to be noted to a lesser extent. To practice the same neglect when considering this game would be a mistake, because Earthbound turns accomplishment in area design into narrative value; measured relative to the technical limitations of its platform and era, it may be one of the most remarkable wielders of space and scale in video gaming.

EarthBound’s transcendence of the typical heroic moral scope, discussed in our first chapter, is what sires the game’s pervasive sense of anything being possible within its bounds. It is through this absence of boundary, combined with EarthBound’s stylization of a childlike perspective, that the game obtains its considerable artistic license when it comes to spatial settings: in a child’s world, anything is possible, from the vastest desert to a city of black streets and living gas pumps. And a world in which anything is possible, or seems it, gives rise to a persistent, nagging sense of impending horror and displacement.

EarthBound’s transcendence of the typical heroic moral scope, discussed in our first chapter, is what sires the game’s pervasive sense of anything being possible within its bounds. It is through this absence of boundary, combined with EarthBound’s stylization of a childlike perspective, that the game obtains its considerable artistic license when it comes to spatial settings: in a child’s world, anything is possible, from the vastest desert to a city of black streets and living gas pumps. And a world in which anything is possible, or seems it, gives rise to a persistent, nagging sense of impending horror and displacement.

In showing us the world through Ness’ eyes, EarthBound brilliantly coaxes the affinities shared between wonder and terror into the light, and displays them to us wrapped in several unforgettably characteristic area settings.

“It Makes Perfect Sense in Moonside”

The marriage of the horrifying and the ordinary pervades EarthBound; if you’re still at Ness’ age (and if you really are, and you are reading this, then good on you!), this marriage is no strange thing. However, to most adults, the horrifying and the ordinary seem diametric opposites, two entities that are practically mutually exclusive. It’s something about childhood: when one doesn’t understand how the world around works, the fact of simply being in the world is scary.

We have seen in our analysis of the Peaceful Rest Valley a measure of how EarthBound can prime entire areas of gameplay for narrative impact, emulating childish terror spectacularly in that instance by making its environments just as unsettling as the enemies that stalk them. What is true for the Valley is perhaps even truer in Moonside.

Let’s set the scene. We have arrived in Fourside, Eagleland’s Manhattan, a burgh so grandiose that the dimensions of its backgrounds seem to loom beyond the perspectival limits of the camera; Ness and his friends no longer stroll at gentle diagonal inclines, or up and across as they have in the obliquely projected towns thus far visited. Everything now seems at a determined slant, everything dwarfed by our new surroundings. Youth’s wonder at scale, and the discomfort it feels of trying to entertain it all at once, is brilliantly evoked thus, and by nothing other than static design.

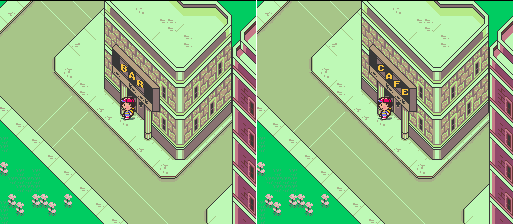

Notice the difference in the player’s viewing perspective in Onett (left) and Fourside (right).

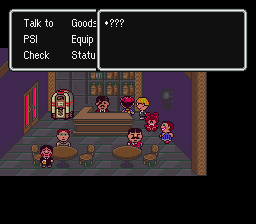

In Fourside, we are looking for the man named Geldegarde Monotoli, who for all his power in commerce and real-estate is the de facto economic king of Fourside, knowing he must be related to the disappearance of our dear kidnappable Paula. After an episode that exploits both the consumerist gleam and the lurking “Stranger Danger” native to a shopping mall, our two underage heroes, Ness and Jeff, go into the tycoon’s favorite “Café.” It is obvious from its speakeasy-type design and the pre-localization screenshots that this place is that most adult of environments: a bar.

The bar in Fourside, pre-localization (left) and post-localization (right).

We’ve been told by a “friend” of a conspiracy concerning Monotoli. Monotoli is, for all his high society, a thief of some caliber: a thug with a briefcase and considerable police protection. To find our kidnapped friend, we must check that place where surely no kid has ever ventured before: behind the counter.

What Ness and Jeff discover there is the entrance to Moonside. Moonside is much the same city, as far as a civil engineer would have it, as Fourside; but this one’s streets are black and its buildings are decked out in gaudy neon colors. Fire plugs, gas pumps, and even simulacra of the melting clock from Dali’s The Persistence of Memory roam around, awaiting an opportunity to attack our heroes; in one of EarthBound’s most justly famous comic touches, we might be stalked through the streets by roving Abstract Art.

What Ness and Jeff discover there is the entrance to Moonside. Moonside is much the same city, as far as a civil engineer would have it, as Fourside; but this one’s streets are black and its buildings are decked out in gaudy neon colors. Fire plugs, gas pumps, and even simulacra of the melting clock from Dali’s The Persistence of Memory roam around, awaiting an opportunity to attack our heroes; in one of EarthBound’s most justly famous comic touches, we might be stalked through the streets by roving Abstract Art.

It seems that EarthBound, a game that flatters the adult in young gamers as it revives the youth in older ones, cannot stop mining its value dichotomies for a minute. Moonside as a whole invokes the strangeness children can feel even for notionally orderly environments. The Abstract Art enemy parodies the distaste and equivalent displacement that the unordered strangeness of weird art inspires in adult consciousness. Such art invokes wonder as freely as terror—perhaps in the context of a controlled medium like art, ‘horror’ would be a better word.

It is perhaps for this reason, EarthBound suggests with a faint wink, why Abstract Art repulses many an adult mind: because it reminds us of a time when the whole world felt at once so wondrous and without limit, and so ontologically and teleologically uncertain.

It is perhaps for this reason, EarthBound suggests with a faint wink, why Abstract Art repulses many an adult mind: because it reminds us of a time when the whole world felt at once so wondrous and without limit, and so ontologically and teleologically uncertain.

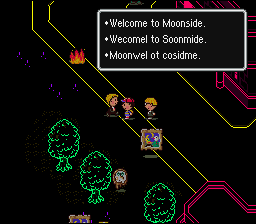

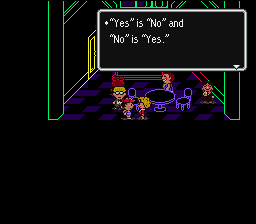

As for the citizens of Moonside? They are more deranged even than the de rigueur in EarthBound. Here, “‘Yes’ is ‘No’ and ‘No’ is ‘Yes’…”; characters will greet you with a cheery “Moonwel to Comeside!”; others will, un-self-consciously blessed with dominion over time and space, teleport us to other areas in this illusory city, but never out of it, with a cheery “Hello…and goodbye!”

We see so much in Moonside that makes us consider things that inspired wonder and/or fear in us as children:

- Fires that we are warned as children to keep away from at all times.

- The tantalizingly adult and difficult-looking gas pump.

- Adults that say things that you cannot understand.

The banal evil of Moonside is that it makes actual and colorful the very real childhood sensibility of not understanding the world.

We alluded briefly in the first installment of this series to the use of ‘pure space’ in the Dusty Dunes Desert to create a sense of the unremitting, of a world that was too huge and complex to ‘care’ about our hero and his quest. Moonside, more literally than the Desert or the Peaceful Rest Valley before it, demonstrates through its characterization and aesthetic presentation EarthBound’s masterly usage of pure space as a banal and disinterested evil, and as a carrier of narrative dread.

We alluded briefly in the first installment of this series to the use of ‘pure space’ in the Dusty Dunes Desert to create a sense of the unremitting, of a world that was too huge and complex to ‘care’ about our hero and his quest. Moonside, more literally than the Desert or the Peaceful Rest Valley before it, demonstrates through its characterization and aesthetic presentation EarthBound’s masterly usage of pure space as a banal and disinterested evil, and as a carrier of narrative dread.

We eventually come learn that Moonside is wholly an illusion, a phantasmagoric safehouse for Monotoli’s dark secrets; and yet we see actualized within it the ‘evil’ wreaked upon children lost in the big city, with no conception how to escape—or, indeed, any conception that escape is possible.

Ness and Jeff enter this area voluntarily; there is no explanation then of why this place exists, who made it, if those who people it are real, and why its inversion of logic and sense are as they are. It is a beautifully designed outpost of the banal and evil because it exists beyond the heroic purpose.

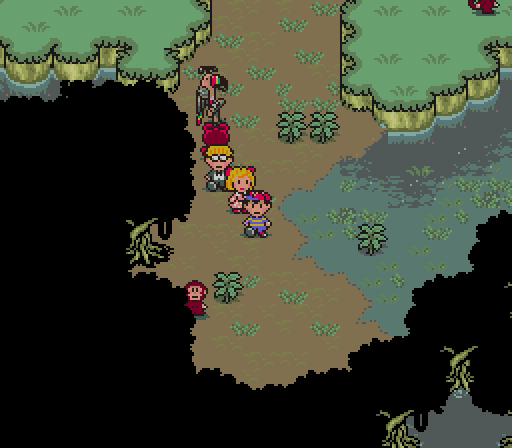

Into Deep Darkness

Deep Darkness, for all the grandeur of its name, seems perfunctory enough as a region, beyond acting as yet another means by which Itoi can flush the gamer full of that ‘distraught’ feeling; its poisonous bogs, the way that progress through them is so dreadfully slow, seem a cheap manner of invoking this sentiment in the gamer. Indeed, just as the Peaceful Rest Valley carried the essence of distraught frustration, Deep Darkness seems to carry the essence of a boredom that slowly develops into that hopeless distraught sensation. Though boredom seems perhaps the most intractable basis possible for a gaming exercise, this region of EarthBound manages to exploit this emotion by manipulating the intrinsic relationships between gaming space, time, and the feeling of progress that a gamer necessarily builds in the course of a one-player experience.

It is not the amount or arrangement of space in Deep Darkness that is remarkable, as it is in the Dusty Dunes Desert or in Moonside/Fourside or in Dalaam, but rather the manner in which we are able to pass through it: we move through this great swamp, into which our heroes sink to the crown, at a sluggish pace.

It is not the amount or arrangement of space in Deep Darkness that is remarkable, as it is in the Dusty Dunes Desert or in Moonside/Fourside or in Dalaam, but rather the manner in which we are able to pass through it: we move through this great swamp, into which our heroes sink to the crown, at a sluggish pace.

This place has none of the wonder of Moonside, nor does it have its frenetic uncertainties. Rather, Deep Darkness is a space designed specifically for the gamer’s encounter with pure boredom, not even enlivened by any great combat challenge. It is the sheer duration of our slog through Deep Darkness – and the small fact that, after a certain point is reached, the region is consumed in (wait for it) the deepest and most impenetrable darkness – that quickly ferments this mere boredom until it has turned into a by-now familiar hopelessness and, as in Moonside, helplessness.

Just as Moonside represents something about a child’s wondersome mistrust of scale, Deep Darkness purposes the relationship of space and time (i.e. the rate of movement) to demonstrate a child’s mistrust of time.

Just as Moonside represents something about a child’s wondersome mistrust of scale, Deep Darkness purposes the relationship of space and time (i.e. the rate of movement) to demonstrate a child’s mistrust of time.

Deep Darkness’ scale is not so much its space; it is how that space seems hyper-extended by the amount of time required to cross it. Children fear great expanses of time; an adult replying to a request with “in a minute” or “maybe tomorrow” seems like a prison sentence. Only as adults do we eventually realize that all time passes anyway, and the future will, in time, arrive.

Nonetheless, there are points in Deep Darkness where we wonder if we shall have to endure the ‘pain’ of deathly slowness forever. The color palette of the area, so attenuated and sickly, suggests as much; we fear that this is an area too poisoned to host life, that we will not be able to move quickly enough, and that we will succumb.

Only the odd, rudely red-petalled flower blooming out of the slime suggests otherwise, and even still isolates us in our quandary; this may be EarthBound, but it seems extraordinarily unlikely that we would be able to consult local flora as to how best survive in our present environment. Thus, the deployment of space in Deep Darkness recalls us to a theme in EarthBound we visited earlier: that we are alone, we have only ourselves, there is nothing about our surroundings that will seek out our hand and hold it.

Only the odd, rudely red-petalled flower blooming out of the slime suggests otherwise, and even still isolates us in our quandary; this may be EarthBound, but it seems extraordinarily unlikely that we would be able to consult local flora as to how best survive in our present environment. Thus, the deployment of space in Deep Darkness recalls us to a theme in EarthBound we visited earlier: that we are alone, we have only ourselves, there is nothing about our surroundings that will seek out our hand and hold it.

A place like Moonside explodes our sense of wonder and terror, giving us maximum quantities of both; Deep Darkness does the inverse, retracting one and seeing how the other wilts along with it, using nothing but a simple design choice and a supremely effective movement gimmick to do it. In Deep Darkness, EarthBound does with emptiness what most games cannot achieve with the most lush and lavish of settings: it makes us confront the pain of our own boredom, of our feelings of being without, that come when there is little else to distract us.

“The Place of Emptiness”

Speaking of emptiness, we have barely spared a jot of ink thus far into our Theory for the fourth member of EarthBound’s heroic party: the princely martial artist, Poo. His space in the group has laid empty of mention or consideration until now.

It is entirely possible that the enigmatic figure of Poo may hold the answers to untold secrets in EarthBound; his is one of the work’s least penetrable personalities. Yet, when we first meet him, he journeys to a place, and undergoes an ordeal there, that epitomizes so much about the confrontations EarthBound as a whole would have us face. The ‘Mu training’ that Poo undergoes shows so much about the way the game employs both spatial and spiritual ‘emptiness’ as a thematic catalyst.

It is entirely possible that the enigmatic figure of Poo may hold the answers to untold secrets in EarthBound; his is one of the work’s least penetrable personalities. Yet, when we first meet him, he journeys to a place, and undergoes an ordeal there, that epitomizes so much about the confrontations EarthBound as a whole would have us face. The ‘Mu training’ that Poo undergoes shows so much about the way the game employs both spatial and spiritual ‘emptiness’ as a thematic catalyst.

Often, EarthBound gleefully preys upon our anxieties and feelings of uncertainty. In Poo’s chapter, the game uses space in order to interrogate where those feelings come from, and why.

After Ness and friends consume a little cake by the ocean in Summers, they undergo what is ostensibly a drug trip; we awaken in Dalaam, now in control of a young Eastern prince named Poo, whose countenance (and, it would appear, voice) bears a certain resemblance to Ness’ own. The implication by all counts is that Ness and Poo share something more ontologically intimate than a mere telepathic connection, though the game never really resolves it or elaborates very much upon it.

At any rate, Poo must set off, seemingly in the manner of all ascetic Eastern heroes, to complete his final rite of spiritual passage.

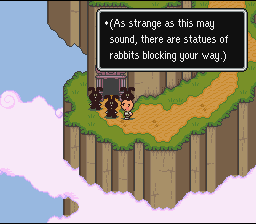

Before we get to the “place of emptiness” where Poo will undergo this trial, Dalaam presents to us the other face of EarthBound’s feel for settings: where other regions have invoked fear through claustrophobia, darkness or vastness, Dalaam is all gloriously winding steppes and pink clouds wandering deferentially beneath high mountain peaks. It really does feel like an American kid’s vision of the East come to life: all Zhangjiajiean floating mountains dotted with straw-roofed houses, whose tenants ponder philosophically to themselves. It is one of the most wondrous places in all of pre-3D gaming.

Before we get to the “place of emptiness” where Poo will undergo this trial, Dalaam presents to us the other face of EarthBound’s feel for settings: where other regions have invoked fear through claustrophobia, darkness or vastness, Dalaam is all gloriously winding steppes and pink clouds wandering deferentially beneath high mountain peaks. It really does feel like an American kid’s vision of the East come to life: all Zhangjiajiean floating mountains dotted with straw-roofed houses, whose tenants ponder philosophically to themselves. It is one of the most wondrous places in all of pre-3D gaming.

Yet, by the time we have gotten where we are going, that familiar sense of dreaded scale has returned. Far from the affable mountainfolk and charming scenery of Dalaam, Poo must now climb high onto a rocky outcrop, where the height of the mountains and the thinness of the air suddenly feel real and disquieting. Like in the Dusty Dunes Desert, there are few—if any—signs of life here, and none whatsoever of civilization.

The “place of emptiness” in Dalaam is a spatial parallel of the state of mu, of being without, that Poo is expected to attain there. Unlike other vast regions of EarthBound that use their spatial mystery and scale to swamp us then with tangible and ultimately life-affirming challenge, we are left purely alone on this outcrop, totally without.

The “place of emptiness” in Dalaam is a spatial parallel of the state of mu, of being without, that Poo is expected to attain there. Unlike other vast regions of EarthBound that use their spatial mystery and scale to swamp us then with tangible and ultimately life-affirming challenge, we are left purely alone on this outcrop, totally without.

But the thing about this state of mu is that it is intended, in Buddhist thinking at least, to be a positive sense of being without; when Poo’s body is taken from him during the training, he, like we, are left without our overriding sense of selfhood. We become something like indivisible from the landscape around us.

In a way, Poo’s disembodiment mirrors our own: in switching on a console and firing up a game, we are willing ourselves towards a certain disembodiment, accepting an invitation to become the living spirit in the machine. During the single-player experience at least, we are within ourselves and with ourselves only.

This can sire wonder, or else terror.

“…where you least want to look”

It is the ‘place of emptiness’ that demonstrates the ways in which setting, place, and space are used by EarthBound for the game’s attempted defeat of dualistic truth. We have explored already how simple moral dichotomies are challenged by EarthBound’s esoteric moral spectrum, and will explore them further in future chapters; we have explored how the lack of moral definition and heroic significance can create the sensation of fear and even despondency in a player, first through narrative and now through space. Reconciling the two, the picture we have is of these characters, both good and bad, that are not so much separated by moral camp as much as they are indivisible from the greater sum of the land and from one another. They are so close that they disallow the discrete and distinct dualistic premises of good-vs.-evil to gain and hold traction.

The likes of Moonside and Deep Darkness are ‘scary’, especially through our child-again eyes, because it seems like we cannot escape them. EarthBound argues that you can’t: it suggests that you can only overcome their challenges by going deeper into their respective hearts of darkness until, as the spirit of Mu says to Poo, “[they] take your mind.”

Perhaps if we succeed, as Poo does, we will emerge from the emptiness as Poo does, as Ness and the rest do: stronger. We come out of it with renewed appreciations: perhaps loneliness, a moment of returning to nothing, an embrace of incomprehension, can be good. We may be obliged to go where we least desire, to a place of infinite terror, a state of being without; but from thence comes the wonder and the strength we most desire.

[1] Carl Jung, Alchemical Studies. R.F.C. Hull (Trans.). The collected works of C.G. Jung (Vol. 13). Bollingen Series XX. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Continue Reading

- A Comprehensive Theory of EarthBound series navigation: < “A Guide to Nihilism in EarthBound“ | “Better the Devil You Notice: The Enemies of EarthBound” >