I’m unbelievably excited about the HD remake of Final Fantasy VII. What better way is there to honor one of the greatest games of all time than to give it the graphical content that it deserves? In the wake of its announcement I felt I should write something, so I decided to follow With a Terrible Fate‘s example of analyzing one particular moment of the game, and why it worked so well.

In the first disc of Final Fantasy VII, after Cloud gets out of Midgar, which he barely escaped with his life, he spends a night in a tavern with his team. Cloud’s goal that night is simple: convince his team that a man named Sephiroth is a danger to the world and must be stopped. In order to convince them, Cloud tells a story– a story of his first encounter with Sephiroth at Nibelheim. What’s interesting about this story is that the player takes control of Cloud’s actions during the story.

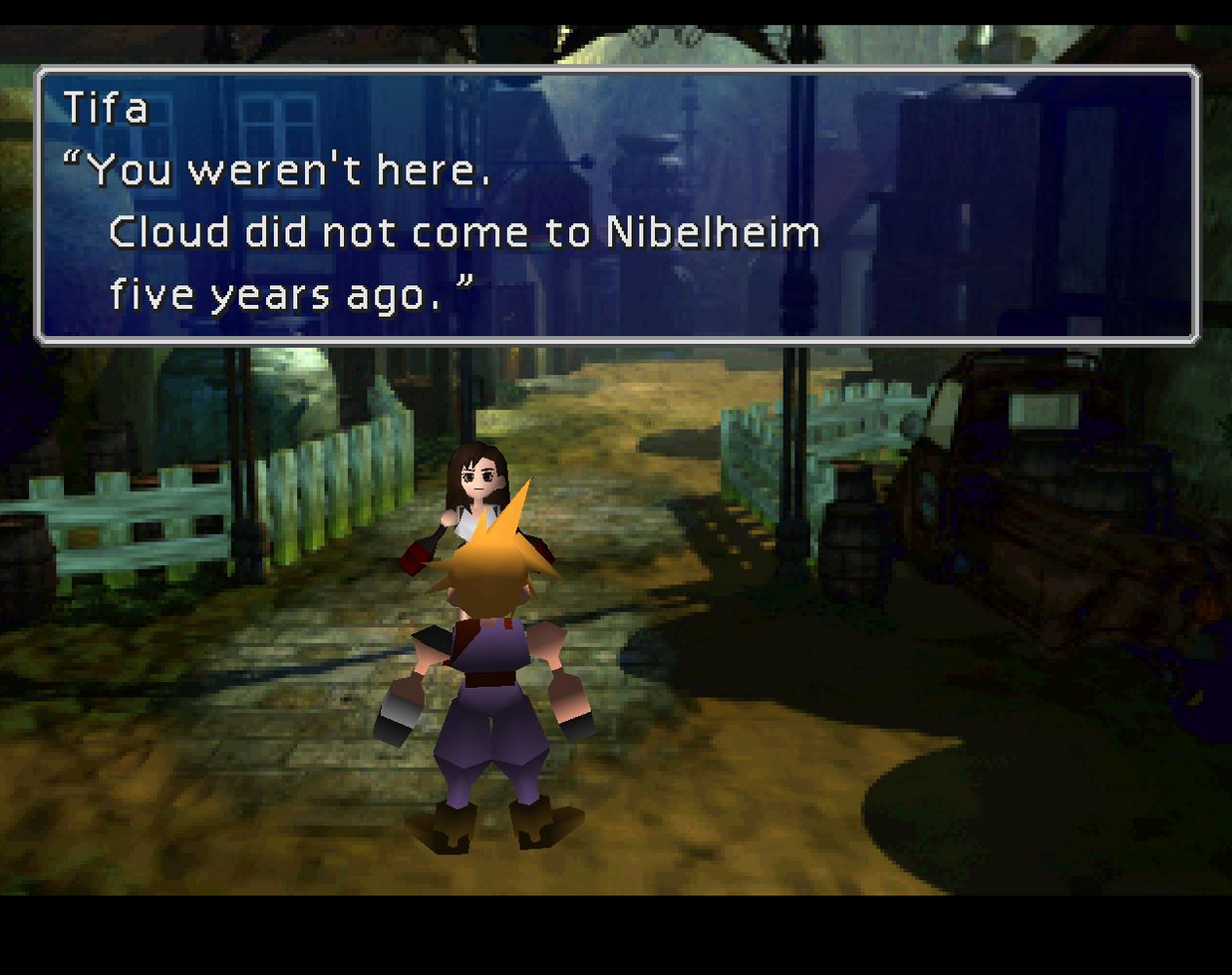

Cloud recalls being dispatched to Nibelheim with Sephiroth by SOLDIER, an elite branch of the Shinra army, to take care of some monster problems in the area. So in the sequence he and Sephiroth go to the town; Sephiroth begins to turn bad, so Cloud confronts him. What the player probably does not know at this point in the game, however, is that Cloud’s memories are actually misattributed. Cloud’s memories describe events that happened to a man named Zack, not to Cloud.

Final Fantasy VII is largely a story about the identity of Cloud, and the second of the game’s three discs features several moments where Cloud’s memories are proven false, fragmenting his sense of self. Cloud’s encounter with Sephiroth at Nibelheim is one of several of the memories proven to be flawed. The process of Cloud’s identity falling to pieces is difficult for the player to watch for two reasons: one, because the player participates in the construction of Cloud’s identity; and two, because the player shares some of Cloud’s flawed memories. The process of playing through the Cloud’s memory sequence at Nibelheim both leads to the player helping to construct Cloud’s identity and also to the player sharing the memories with Cloud. So now we must answer two questions: Why does playing through the memory sequence allow the player to form Cloud’s identity more than just watching it allows? And, why does the player share these memories with Cloud?

Let’s start with the second of those two questions. Within a memory, one of the essential parts is memory of action. By nature of Cloud being an avatar for the player, the player can sometimes determine Cloud’s actions. Thus, in the memory segment in question, since the player can determine some of Cloud’s actions in the past, the player is actively taking a role of action within the memory. The memories in the sequence also in part become the memories of the player, which the player assumes to be true within the work of fiction, since she was the one who acted in the scenario.

To answer the first question — “Why does playing through the memory sequence allow the player to form Cloud’s identity more than just watching it allows?” — let’s take a look at Psychodynamics. Psychodynamic theory postulates that a person’s identity is directly linked to their interpretation of their past. In the process of remembering, a person reinterprets their memories. Memory is dynamic in the psychodynamic view: each time one remembers an event, their interpretation has the potential to change. When Cloud tells the story of his memory in Nibelheim, he is creating an interpretation at the same time. And since the player controls Cloud’s actions during the memory, she is part of the creation of his interpretation of events. The player participates in creating Cloud’s current interpretation of his past, and thus participates in part in the creation of Cloud’s identity.

Since the player both has a personal memory of certain events in Cloud’s past and also has helped shape his interpretation of those events, the player has a difficult time accepting challenges to Cloud’s identity and these memories as false within the fiction of the story. She helped create the memory and, by extension, Cloud’s identity. It makes sense then that when the player finds out that the Nibelheim memory sequence was misattributed, she resists that conclusion. Watching Cloud’s memories and identity fall to pieces ends up being an extremely difficult experience for the player in part because she played through some of the experiences that turn out to be misattributed. The connection between the player and Cloud’s identity becomes very strong by the end of disc one.

Square took advantage of a particular feature of video games to give their game more impact. That feature of video games is that playing a story, as opposed to just hearing a story, makes the player more naturally inclined to trust the sequence of events that unfolds before them, since she helped create them. There are of course cases where this is not true, in which the player is given ample reason not to believe the reality that is being presented to her (for examples of this, I point the reader to the “Batman: Arkham” series’ Scarecrow sections and “The Stanley Parable” Insanity Ending). But when it becomes clear that Cloud’s identity was manufactured from misplaced memories, the revelation takes on more impact because the player could control Cloud during his manufactured memories.