The following is part of Now Loading, a series that renders verdicts on whether or not your favorite video games deserve a place in the canon of works that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. Read the series’ full mission statement here.

At PAX East 2018, we asked the audience to help us decide whether Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door belongs in the video game canon—the group of video games that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. I can’t say I had a good answer going into and even coming out of the discussion, mainly because good points were raised on either side of the argument about this game.

Now, I’ve had some time to mull things over, and I’d love to share my thoughts with everyone…

A classic of our generation. Thanks, Nintendo.

LET’S-A GO

Somehow, I totally missed the boat on playing Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door back in the day. The first Paper Mario game I played was Super Paper Mario for the Wii, and I have a vivid memory of frustration with that game, largely thanks to my own gaming stupidity.

In Super Paper Mario, there is a segment where Mario has to pay off a debt. One way he can do so is by running on a glorified hamster wheel to generate electricity and slowly earn money; this method takes an extremely long time, unless the player snoops around and finds a stash of money to pay off their debt quickly. Being an amazing gamer, I tried to position a book on top of my Wii remote so that Mario would keep running forward and I could walk away from the game and come back later…

…which didn’t work.

The horror…the horror…

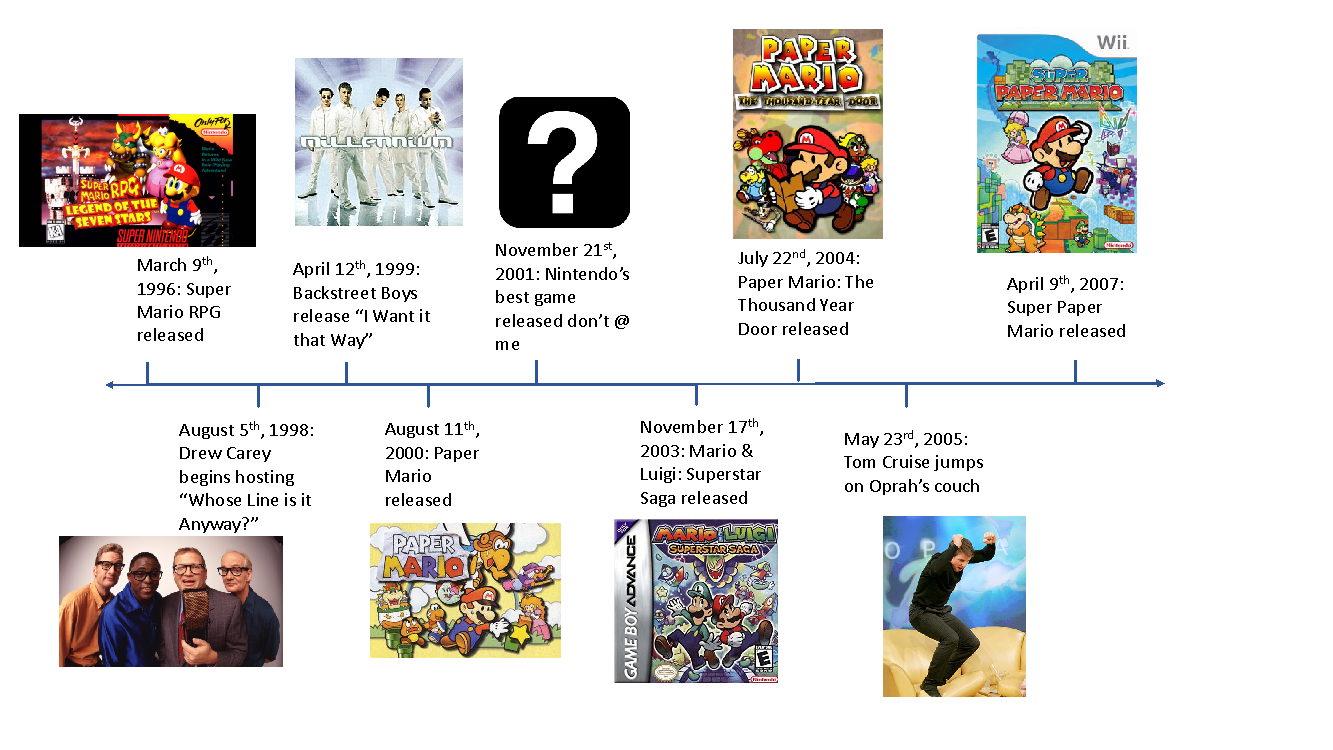

Upon throwing the game disc in frustration, I found, in its wake, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door. The second installment in the Paper Mario franchise, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door was released for the GameCube in 2004. Nintendo had begun working on Mario-inspired RPGs in the late 90s, releasing Super Mario RPG for the SNES in 1996, followed by the original Paper Mario title in 2000 for the Nintendo 64. These were quickly followed in 2003 by another RPG, this time for the Game Boy Advance: Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga.

Super Mario RPG and Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga showcased Nintendo bolstering 4th-wall-breaking comedy that put their well-known Nintendo characters into new situations and often forming new, unexpected relationships. Super Paper Mario expanded on this idea by forming a new kind of Mario title that was set up to look like a play, insinuating that all of the Nintendo characters are here to put on a show for the players.

All to say, there was a lot of buildup and experimentation in the RPG genre by Nintendo leading up to Thousand-Year Door. And Nintendo continued to work on this genre with future releases—like that disc I threw in frustration, Super Paper Mario for the Wii in 2007.

That’s a lot of paper and dates to keep track of, so I’ve made a timeline to help everyone:

As we’ll see, Thousand-Year Door is game that takes a lot from its predecessors and isn’t afraid to wear its influences on its sleeve. It’s this mixture of many titles and ideas that helps to make this game truly unique and incredibly enjoyable. In many ways, Thousand-Year Door actively screams to the player that what they are playing is a video game, changing the player’s relationship with the medium, the fiction, and the characters. This game truly takes the meaning of ‘role’ in ‘role-playing games’ literally, and by doing so creates a well-constructed and engrossing narrative.

Story and Characters: Messing with the Mafia

The story begins with Princess Peach at the town of “Rogueport,” where she has sent a letter to Mario to come and help her find treasure using a map she has recently found. To no one’s surprise, Peach gets captured. However, to many people’s surprise, she is captured not by our favorite fire-breathing turtle but instead by a group known as the X-Nauts, led by Sir Grodus.

When Mario arrives at Rogueport and learns of Peach’s kidnapping, he sets out to find and save her. He also discovers that her treasure map contains the locations of the seven “Crystal Stars,” which can be used to open the “Thousand-Year Door” that is fabled to contain treasure. The X-Nauts are similarly after what lies behind this door, which leads to several encounters between them and Mario throughout the story.

And thus, you already have a slightly different take on the classic Mario trope: instead of rescuing a princess from a single-minded kidnapper, he’s rescuing her from a legion of thieves who are hunting for the same treasure that he is.

The story itself is set up like a book or a play, with specific chapters corresponding to a new land to which Mario travels in search of a Crystal Star, finding a litany of new teammates along the way. Some of the teammates Mario meets include Goombella, Koops, Yoshi Kid, Madame Flurrie, Admiral Bobbery, and Vivian. This setup to the story is similar to the chapters of the original Paper Mario, which harks back to the much older idea of making Mario games look like a play. That idea dates all the way back to Super Mario Bros. 3.

This story format flags to the player that what they are witnessing may simply be a performance, a theme uncommon in many RPGs and generally contained to the Paper Mario series at the time. Many other RPGs have the player move through different areas on a map with companions and engage in turn-based battles and stat-building; Paper Mario games also have these aspects, but, in Paper Mario games, the battles take place on a stage and the story is divided up like a storybook, like a game of make-believe.

Such a setup causes the player to think differently about their relationship with the game and the characters in a way that other RPGs and other single-player games do not. Paper Mario games cause the player to almost feel as if they were literally playing a role, or a part in a play, within a role-playing game—an aesthetic almost diametrically opposed to the “total immersion” philosophy of games like Skyrim that aim to make the player forget the line between fiction and reality.

The many colorful characters of Thousand-Year Door.

Now, it is true that there’s a lot of similarity between the original Paper Mario and Thousand-Year Door, down to the collection of seven star-based items, the different teammates Mario meets and their abilities, and the structures and lands encountered within different chapters. But, I don’t want to make this article a debate about which game is better – we are here to evaluate Thousand-Year Door.

It is definitely a valid criticism of Thousand-Year Door that it uses a lot of the same material and style that its predecessors used. However, where Thousand-Year Door succeeds is the degree to which it expands upon certain ideas of its predecessors, and that is where I would like to focus our attention.

Let’s start with the structure of the story. To the established structure of story chapters, Thousand-Year Door adds the element of intermissions, wherein the player can control Peach or Bowser. Peach deals with a computer system that is infatuated with her while she is in captivity, whereas Bowser just tries to make himself relevant again now that he’s been sidelined by Nintendo in favor of a new, fresh villain.

These intermissions expand upon the story and make it seem more like a play, with various scenes following different characters. In addition, similar to Super Mario RPG and unlike the original Paper Mario, Bowser acts as a caricature of himself that helps to reinforce this idea that the relationships between the characters may not be as high-stakes and that the characters may instead be acting within some play. Overall, these intermissions bolster the idea that everything is just a performance, and specifically a performance in which the player, by controlling Mario, is an active participant.

Bowser can’t catch a break.

Thousand-Year Door also features myriad examples of playful or quirky humor. One of my favorite segments of the game involves Mario getting involved with a criminal organization of Piantas (from Super Mario Sunshine), essentially a Pianta mafia. That in itself is great, but mix in a love story, Brooklyn accents, and a leader named “Don Pianta,” and we have ourselves a Nintendo version of The Godfather.

“Leave the gun, take the cannolis.”

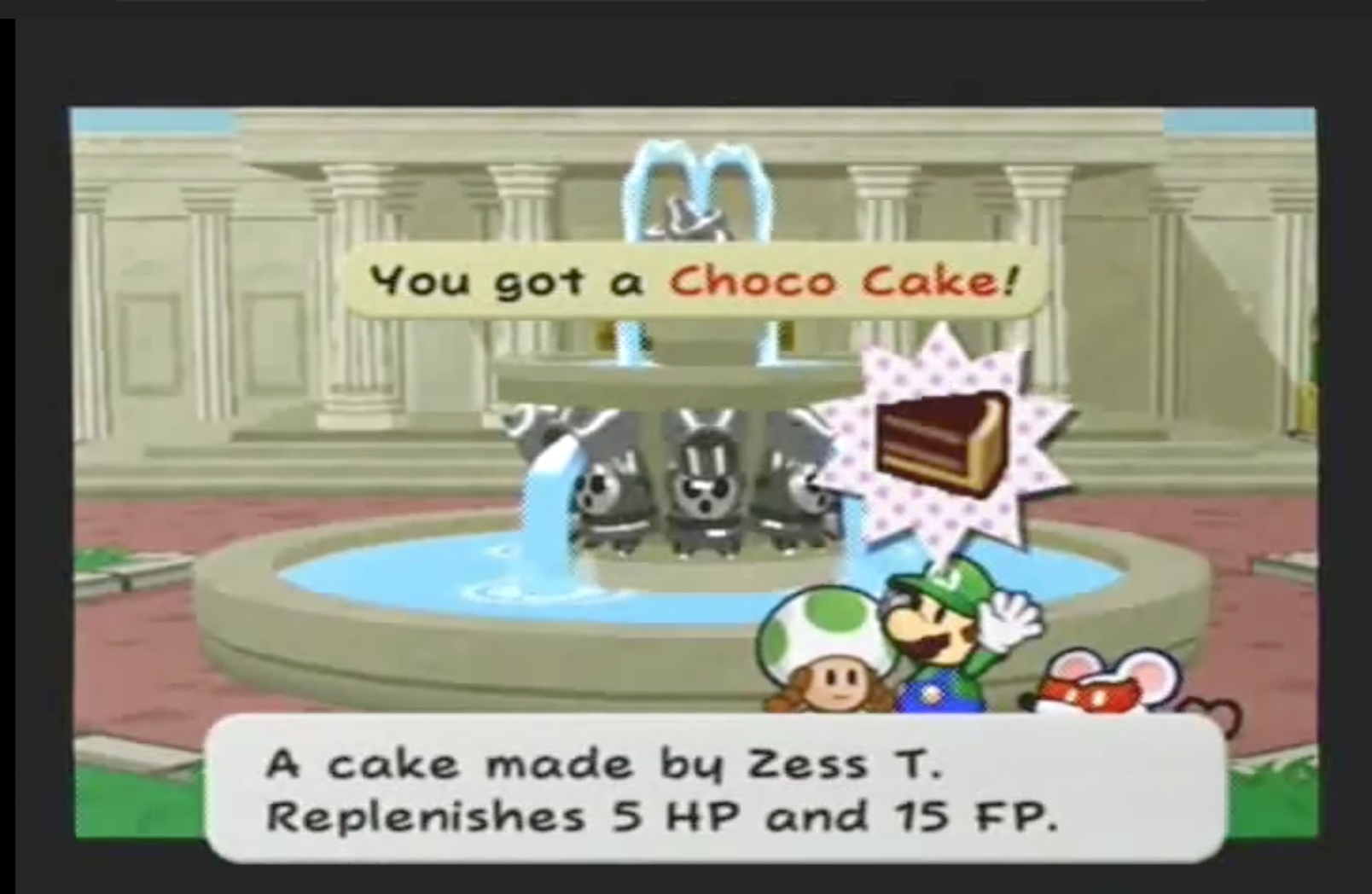

Another great moment of the game is when Mario can choose to help a character named “Toadia” who wants to meet Luigi. The player can approach Toadia as Mario, who has donned a Luigi costume, in order to fulfill her wish. When the real Luigi appears on the scene, Toadia screams, proclaims him to be a “filthy imposter,” and Luigi flees.

Even when Luigi is wanted, Mario gets the cake.

Luigi didn’t need it anyway.

This playful and quirky humor permeates Thousand-Year Door, and to me is often reminiscent of the weird humor in Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga. Superstar Saga is also another example of a Mario RPG that doesn’t place Bowser at the villain’s driving seat, poking fun at him instead. Thousand-Year Door, like its Nintendo RPG predecessors, is really focused on highlighting the comedic elements of the situation to give the player a funny, interesting experience. In Thousand-Year Door, this humor works in conjunction with an intermission-laden play to create a hilarious theatrical experience for the player to take part in.

Gameplay, Music, and Visuals: Rogueport’s Hair… it’s Full of Secrets

My favorite area in Thousand-Year Door has to be the hub world, Rogueport. As I already alluded to, it’s a town with a lot of personality and interesting characters to talk with, such as the Pianta mafia – there really is a surprising amount of gambling and crime happening, but I guess Nintendo flagged that to everyone pretty obviously with the name.

Rogueport is also a town full of secrets: secret entrances or exits to buildings, and, most importantly, the sewer system below Rogueport. This area is filled with pipes going everywhere and small puzzles to progressively solve over the course of the game; most of the extensions to different worlds come through pipes or secret passages found in this area. This, in addition to the Thousand-Year Door itself, give Rogueport an air of mystery.

The classic Mario underground.

In terms of gameplay, Thousand-Year Door does borrow a lot from its predecessor. In my mind, though, two things really help this game to stand out and make the experience of playing it more cohesive:

- A refined battle system, which the crowd at PAX helped me to really appreciate.

- Paper abilities.

One of the defining features of a Mario RPG game is the use of action commands, which the player can use, with the right timing, to enhance their attacks or counterattacks. This option adds a lot of depth and interactivity to the battle system, as well as challenge. In Paper Mario, this ability was not possible until later in the game, but in both Thousand-Year Door and Superstar Saga, this is present from the beginning.

Endless head-pounding.

Furthermore, the battle system in Thousand-Year Door adds an extra layer in the form of audience interactions. In previous games, battle-encounter scenery looked like a play, but in Thousand-Year Door the player can now interact with the scenery and audience. For example, parts of the scenery may fall on opponents, or Mario can do ‘stylish moves’ to get the crowd cheering and build up his meter for using his special abilities. These details may not seem hugely significant, but, to me, they really help to flesh out the idea that Thousand-Year Door is a play or a storybook. In fact, with this interactivity in mind, this game doesn’t just imply that it’s a play: it shouts that it’s a play at the top of its lungs!

This setup naturally raises a crucial question: is the player is part of the game’s audience, or is the player something else entirely? Perhaps the player is the one orchestrating the play, unknowingly reenacting an adventure Mario already had to an intrigued audience. Battle system details such as these really help to add to the depth of the story and the player’s firsthand experience of the game, and they can even lead to more general questions about the relationship between video-game stories and interactive books. Are video games themselves just interactive books or movies? Is Thousand-Year Door just an interactive book?

Thousand-Year Door truly raises the question of what it means to play a role in a role-playing game. Many RPGs can feel just like any other single player games, with the mere addition of turn-based battles. Thousand-Year Door sets itself up as a comedic performance with an audience closely watching each intense moment and even affecting the fighting itself. The player both witnesses and takes part in the unfolding of this story and plays a role, or some acting position, within it. Such a format is a unique take on the RPG genre, and one that can perhaps cause the player to interact more intimately in what they see as a literal performance that they are helping to orchestrate.

Note the large audience at the bottom.

Thus, Thousand-Year Door clearly expands upon previous ideas in order to create a unique gaming experience.

Impact on Video Gaming and Culture: This Game Needs a List of References

As we saw at the outset, Thousand-Year Door has many predecessors and successors. One of these is Super Paper Mario, which expands upon the ideas of the series even further by allowing Mario to flip between 2D and 3D.

Thousand-Year Door contains myriads of references:

- Collecting Shine sprites (Super Mario Sunshine)

- Visiting the town “Petalburg” and collecting sun and moon stones (Pokémon Ruby/Sapphire)

- Luigi occasionally carries his famous vacuum (Luigi’s Mansion)

- Princess Peach sings a familiar song from Super Mario 64 during one of her intermissions

- And the list

- Goes on

- And on

Someone find me an Eevee.

Clearly, the game itself took a lot from those around it, while also tying everything together into a cohesive story that gives a lot back to its audience. Taking disparate elements from other games and combining them to make something new and wholly more interesting: that’s what these RPG games are about. By referencing all of these games, Thousand-Year Door is not only calling out itself as a video game performance but also humorously pointing out, and often poking fun at, other games.

BONUS LEVEL: The Nintendo Complex

One of my favorite points raised during our PAX East discussion was whether or not we would hold Thousand-Year Door in as high esteem if the game had not been from Nintendo. Are we biased to just be excited by seeing Nintendo do something new or give us a game with variations on past games? Would the answer change to whether Thousand-Year Door is part of the video game canon if it were not a Nintendo game—if it were simply Paper Man: The Thousand-Year Door?

I would say no.

Regardless of Thousand-Year Door being a Nintendo game, all of our previous investigation still holds from a general standpoint. Thousand-Year Door takes a lot of influence from past games and utilizes it to tell an even better story with more engaging gameplay and characters. More importantly, the game actively discusses the idea of role-playing in a satirical way. For a game to do so, it doesn’t need to have roots in a well-established game franchise; the most important elements of this game came more so from the story’s structure, the battle system, and the humorous dialogue. The Mario-centric identities of the characters aren’t as relevant.

One could imagine taking the storytelling elements and battle system from this game and slapping on a new set of characters with the same level of humor, and the result would be a similarly rich and RPG-challenging story. The fact that Thousand-Year Door also includes our favorite Nintendo characters is just a great bonus to make gamers’ nostalgic mouths water.

VERDICT: An Explosive Welcome

Thousand-Year Door is a fantastic game that takes full advantage of its resources. And, in doing so, creates an engaging and nuanced experience for its gamers. Let me end with a quote from everyone’s favorite character, Flavio:

And yet…why is it that a man whose life is unchained must always long for more, ah? What is missing from my life?

The video game canon, obviously.

Welcome, Thousand-Year Door, to the video game canon!