The following is part of Now Loading, a series that renders verdicts on whether or not your favorite video games deserve a place in the canon of works that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. Read the series’ full mission statement here.

It Wouldn’t Be a Canon without an Arms Race

Welcome, dear readers, to the latest installment of Now Loading…The Video Game Canon! The only weekly Internet column that examines video games from the past to determine whether they should be left to rot in the collective cultural dust, or immortalized in the Game Hall of Fame!

This week, I’m taking over to provide Dan with some much needed R’n’R while I exhume the bullet-ridden, tread-marked corpse of Grand Theft Auto III to definitively decide whether it belongs in the video game canon. I know, I know – this might seem like an exercise in redundancy, what with GTAIII being one of the best-selling games of all time, the recipient of widespread critical acclaim, and generally agreed to be one of the most influential entries in a highly impactful franchise. Still, much has changed in the gaming landscape since Rockstar Games first brought their flagship series into the third dimension, and here at With a Terrible Fate, we tend to turn our noses at the so-called certainties of conventional wisdom.

Also, my friends and family are getting a little tired of my prattling on about the lasting cultural impact of GTA, and they thought it might be healthy for me to find another outlet.

It’s been almost two decades since GTAIII’s initial release on the PlayStation in 2001, and if you strain your ears and tilt your head just right, you can still hear the faint sounds of the last outraged cries dying off. Seriously: it might be hard to recall or conceive of in our current era, but there was a time when the biggest threat to the morality of America’s youth seemed to be a video game rather than the oval office. Although far from the first console title to depict graphic violence, GTAIII became a poster boy for “mature gaming,” focused as it was on providing players with a cornucopia of cavalier criminality to indulge in: sex, drugs, guns, and enough fast cars to fill a scrap yard.

Indeed, it’s impossible to overlook how foundational the gameplay is to the story, and to the subsequent controversy that stemmed from the game. Executive producer Dan Houser is on the record as saying that the mechanics and the story were developed concurrently, so as to complement one another.

But as sensational as the content of the main plot’s missions might be, the true culprit behind the infamy of GTAIII is the freedom belonging to the player and the mischief-making it allows for. There is no narrative requirement to procure the services of a prostitute and then killing her to get your money back; there is no pressing plotline that demands you blow up a bus with an RPG. Rockstar’s great supposed sin isn’t so much that they force the player into depraved criminality; rather, they built a world perfectly suited for depraved criminality, said “Have fun,” and then left the room.

One is just as capable of driving the speed limit, obeying stoplights, and living a leisurely life of legal taxi-driving and fire-fighting in GTAIII as they are of murderous rampage – it just so happens that the latter option is a lot more fun.

Story and Characters: A Good Old-Fashioned Gang War

In contrast to the neon nostalgia of Vice City’s pseudo-Scarface storyline, or even to the fantastical gangland epic of San Andreas, GTAIII’s plot is much more straightforward, even simplistic.

Set up from the outset as a tale of revenge, the game implements a pastiche of Scorcesean Mafioso narratives, hardboiled noir, and cheeky lampooning of pop culture (the latter of which would become an infamous staple of the series). As mentioned, the developers clearly meant for the mechanics and world to inform the narrative, rather than the other way around, with the stated goal of creating a “living, breathing 3D world.” Although I myself am a vocal proponent of form that reflects content, in this case the reversal makes sense: the main story of GTAIII is about the player interacting with and running amok inside of Liberty City.

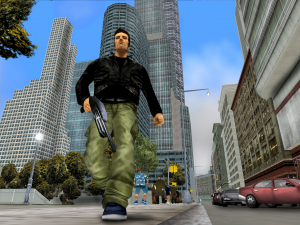

In keeping with this approach, our protagonist is Claude, a silent antihero who is more of a blank canvas upon which the player can project themselves than a fully developed character in his own right (think Zelda’s Link, but clad in cargo pants and a leather jacket). His name wasn’t even revealed until San Andreas, rendering him even more of an explicitly vacant avatar.

At the same time, the central plot of the game is one unique to Claude’s personal life: a quest for revenge against Catalina, the Bonnie to his Clyde, who shot him and left him for dead in the game’s opening cutscene. In this way, by making the broader narrative tied to its protagonist, the game can afford to leave the majority of his character undeveloped, relying instead on a clearly established motivation and a calm, quiet demeanor that works as an ideal counterpoint to the bombastic mayhem the player can wreak within the game’s world.

Seriously: imagine how much more controversy would have arisen had the protagonist of GTAIII been GTAV’s Trevor: a loudly maniacal, abrasive, and gleeful psychopath. Apologies for the pun, but this would have been overkill, and would have (rightfully) been viewed as transparently sensationalist—a tone-deaf cherry on top of a particularly violent sundae. After all, Trevor only works as a character specifically within the context of his own game: he is GTA’s id, all of its zaniest and most pathological urges rolled up into one bizarre, murderous cretin. He’s self-satire at its best, in the sense that Rockstar weaponized this otherwise-ridiculous caricature by pairing him with two other, more level-headed protagonists, creating a depth of character and story that is appropriate for GTAV, which, like its direct predecessor, IV, is more cinematic and concerned with narrative than previous entries.

But, to return to our main subject, GTAIII is very much too young and too new a title in the series’ timeline to be concerned with this level of self-reference and depth. The character of Claude provides some breathing room in a game that can be very busy, and ultimately helps build an atmosphere that is more invitational than reflexive.

The supporting cast of GTAIII, then, is there to break the silence and imbue some humanity into the main narrative. Featuring voice acting from cinematic luminaries like Michael Madsen and Kyle Machlachlan, the various pimps, drug dealers, dons, assassins, and businessmen who procure Claude’s services paint a gritty portrait of Liberty City’s seedy underbelly: a cutthroat criminal landscape marked by power, betrayal, and an unholy devotion to the almighty dollar. Characters like Salvatore Leone, the aged and scrupulous Don of the Leone Family, and Asuka Kasen, the cold, calculating, and somewhat sadomasochistic Yakuza higher-up punctuate the game’s narrative with personality, stitching together a dynamic humanity to populate the dark and dreary Liberty City.

At the same time, the warring factions that the player pivots to and from are thinly constructed, primarily defined by ethnicity and loosely based on real-world criminal organizations, from the Triad Chinese syndicate to the Rastafarian Uptown Yardies. In contrast to the outlandish gangs of GTA2 (which featured the likes of the Rednecks and the Hare Krishna), the criminal organizations of GTAIII were a step towards a more authentic portrayal of gang warfare, while at the same time being just two-dimensional enough to sidestep total realism. This balancing act between a true-to-life depiction of crime and a cartoonish display of violent illegality is mediated by the cynical, self-deprecating sense of humor that would become one of the series’ calling cards. Think of the mission “Blow Fish,” wherein Claude is tasked with blowing up a Triad-controlled fish factory via an explosives-rigged garbage truck. This type of tongue-in-cheek objective shares more in common with a pulpy crime comic than anything realistic, and thereby tempers the game with a liberal dose of silliness.

But any discussion of GTAIII’s characters would be remiss to not include Maria Latore, the woman first introduced as Salvatore’s trophy wife who soon becomes a quasi-love interest for Claude, alternately playing the starring role in escort and rescue missions, as well as pushing the narrative along by connecting the protagonist to new contacts and new jobs. Although portrayed as vain, immature, and impulsive (hardly demonstrative of a non-stereotypical female lead), Maria’s relationship with Claude creates some measure of consistency and investment in the storyline, beyond the driving sentiment of revenge. But any whiff of genuine romance is short-lived, as here, too, the lasting impression of the character is tongue-in-cheek: after the game’s final mission, which sees the protagonist succeed in his quest to exact vengeance against Catalina, an off-screen conversation between Claude and Maria is ended by a gunshot, insinuating murder, suicide, or worse.

Although one can interpret that ending as another unfortunate example of (insinuated or not) violence against women in a game that often depicts that subject, there are two major considerations to bear in mind in this regard.

The first is an essential component of any fair-minded analysis of art that engages with violence: depiction is not endorsement (an understanding that extends to every aspect of GTA’s amoral playground – more on that later).

The second is that the ambiguous gunshot is directly in keeping with the bleak and biting brand of satire that is as important to the identity of GTAIII as any rampage or street race. Although the series never set out to make any substantial point about its subject matter, its relentless obsession with the worst aspects of human nature (depicted in an exclusively American context) can’t help but result in the most cutting kind of sociopolitical send-ups. Whether in the “fake news” marketing ploy of the Liberty Tree or the critique of bloodthirsty capitalism embodied by media mogul-cum-cannibal Donald Love, GTAIII communicates eerily prescient takes on violence, criminality, and pop culture – and particularly on the intersection of all three. In this way, the casual and consistent violence (gun violence, especially) is as vital to the storyline as any other character or narrative.

Thus, it’s only fitting that at the end of GTAIII, it’s the gunfire that has the last word.

Gameplay, Music, and Visuals: You Better Drive, Brother

If there’s a single element of GTAIII that hasn’t aged as well as others, it would have to be the gameplay. The driving controls feel clunkier and less intuitive than later entries in the series, making certain missions much more frustrating than they ought to be. The combat system fares even worse, with a notoriously spotty lock-on system that turns firefights into confusing, off-kilter chaos. The feel of using weaponry lacks a visceral punch: firing off a shotgun round or shooting an RPG doesn’t quite feel as weighty and satisfying as in the more sophisticated control schemes of latter-day GTA.

But it’s important to highlight the hindsight coloring these observations: as limp as the gameplay can sometimes be, it was foundational in defining the core mechanics of contemporary third-person shooters and action/adventure games alike, to the point of inspiring an unending litany of knock-offs that still persists to this day. Much like Super Mario 64, which created an entirely new type of platformer for a new generation of consoles, GTAIII brought a new type of game into the world, both structurally and stylistically.

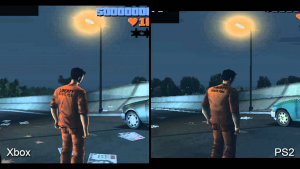

The graphics have aged as gracefully as any game published in 2001 can, and, in my opinion, the bleary, darker color palette of GTAIII exudes a kind of gritty urban charm not present in its sequels.

In the same vein, it’s time for some full disclosure: my formative experiences with this game came not from the original PlayStation 2 edition, but rather the Xbox port released as half of the Grand Theft Auto Double Pack (alongside Vice City) on October 31st, 2003. I vividly recall the fervor that took over my preteen mind when I discovered that these games (which were doubly unavailable to me, being both Sony exclusives and M-rated) took a large leap towards my grasp. As such, the Liberty City I descended into was in much higher definition, with a better draw distance and many, many more polygons – oh, the sweet, sweet polygons.

Anyway, it’s possible that my reevaluation of GTAIII’s graphics is impinged by this fact, but at the end of the day I think you’d be hard-pressed to find a game of that era that still holds its own in the visual department as adequately as GTAIII.

The music, however, has stood the test of time in the way that only the venerated musical selections of Rockstar Games can. Although featuring less big-name artists than later incarnations of the series (indeed, the six-LP, collector’s edition box set of a Grand Theft Auto soundtrack was still years away), the radio stations of GTAIII displayed an eclectic mix of a wide range of music, whether the dub and reggae of K-Jah, the hip-hop of Game FM, or (my personal favorite) the indelible classical compositions on Double Clef FM – because nothing suits bloodsoaked urban warfare like a little Verdi.

Of course, the star of the show is Chatterbox FM, the talk show dedicated to airing out the various, hilarious psychoses of Liberty City’s residents (not to mention those of its host, Lazlow Jones, a writer and producer of the series who would go on to become a recurring character). Here again, we can see the acerbic wit and absurdist humor of the game in full force as Lazlow struggles to contend with his call-in guests. While some conversations take the form of one-off skits (like the veteran of the “Australian-American War”), others give humorous insight into characters from the game’s main plot (as with Toni Cipriani’s motherly troubles) or parody pop culture of the era. An example of the latter is the caller representing C.R.A.P. (Citizens Raging Against Phones), whose vitriolic hatred for phones seems like it’d be just as relevant in 2017 as it was in 2001.

Taken all together, we can see in the radio stations of GTAIII the germ of what would become one of the series’ defining aspects, and a source of entertainment that could literally have you driving around Liberty City for hours doing absolutely nothing, just so you could see what tracks you hadn’t heard yet.

Impact on Gaming and Culture: Give Me Liberty

As I’ve intimated numerous times throughout this piece, the influence of GTAIII over gaming at large (and indeed pop culture in general) can’t really be understated. It was a top-seller for its system that began Grand Theft Auto’s reign as one of the most commercially and critically-successful gaming franchises ever, right up there with the Mario games, Halo, or Metal Gear Solid. Subsequent titles in the series continually revitalized and built upon the foundations that GTAIII had lain to take the series in new directions, whether in the zany, colorful open-world of San Andreas, the more mature and melancholic GTAIV, or GTAV’s current incarnation as the online-gaming powerhouse that GTAIII was originally intended to be.

In each iteration, GTA has only set itself further and further apart from the also-rans it spawned by leaning hard into its most unique and recognizable aspects: the skewering of American pop culture, the satirical tone, and the gameplay-first ethos that kept the formula from getting stale. Although it might seem difficult to disentangle GTAIII from the massive hype machine that it birthed, the fact is that (much like its sequels), when viewed in a vacuum, GTAIII is as entertaining a video game as it’s ever been.

Which brings us back to the nature of that entertainment itself. I won’t waste space discussing any sort of causal relationship between GTA and real-world crime – by this point, that particular horse has been flayed beyond recognition. What I can talk about is my personal relationship with these games.

Sometimes when I mention GTAIII as being one of my favorite games, or Grand Theft Auto as one of my favorite series, I get a questioning look from fellow gamers and the uninitiated alike – a raised eyebrow, or a deprecating chuckle.

“GTA? Riiiight.”

And I’ll readily admit that there’s much to find distasteful in these games, even outside of the crime: the often-juvenile sense of humor, the outrageous plots, a horde of thinly written characters, and the aforementioned casual attitude towards violence against women. But despite all of these things, GTA to me has earned its weighty legacy by virtue of its steadfast devotion to the concept of play.

I mentioned above that when I first played GTAIII, I was likely eleven or twelve, which technically made my playing the game something of a crime. More specifically, it made my parents quasi-criminals for allowing a Mature-rated game into the hands of their immature son. But they only did so conditionally: before my hands ever touched the controller, they both discussed the game with me at length.

What was the game about? Why did I want to play it? Of course, I probably tiptoed my way through this discussion by leaning hard on the “auto” side of things and away from the “grand theft” stuff, but even so, my parents only actually got me the game once they understood what they were allowing me to engage with. And they didn’t let up: my father would often show up unannounced in my room to see what exactly I was doing in Liberty City, and my mother would talk with me about the nature of fantasy vs. reality.

All of this to say that, although there are many gamers who first experienced these games as adults capable of making their own decisions, a great many like me were first exposed to them as preteens and adolescents, and my own initial experience was as mediated by authority figures as it could possibly have been.

With that context in mind, I would unequivocally state that GTAIII and the series proper, beyond being fun video games, were foundationally educational to me in terms of appreciating and understanding violence in art. The fact is that, beneath the superficial, visceral buzz of playing a third-person shooter, I absolutely derived emotional catharsis from playing GTAIII, and specifically from the violence therein.

I didn’t play sports and I was never an aggressive kid, but through video games like GTAIII I was able to exorcise the negative emotions and experiences of my life in a context that was safe, disconnected from consequence, and ultimately (and importantly) temporary. From Tarantino to Shakespeare, Hitchcock to Hemingway, art that depicts or grapples with violence has always been a method for humanity to observe and assess its worst impulses from a removed perspective. Of course, Rockstar Games might not be nearly as concerned with weighty meditations on the human condition as some of those other artists might be, but GTA also differs in the sense that its own art form explicitly requires player agency and input. GTA demands that its audience engages with its violence – it only exists on-screen if the player actively perpetrates it.

You, as the player, must be the one to drive, to punch, to shoot—but most importantly, to play.

And this is the gift of Grand Theft Auto that so many of its imitators failed to realize. It’s not about sheer spectacle or sensationalism or trying to one-up each violent act with another one more graphic or outrageous. It’s about neutralizing the danger and horror of violence and crime through the power of play. Any one of GTAIII’s many missions, if they were to occur in real-life, would be an inarguable tragedy. But the fact is that they don’t, and they aren’t, and that makes all the difference.

GTAIII takes the ugliest realities of our modern world, takes them out of reality, defangs them, renders them silly, and blows them out of proportion, until they exist in an entirely new context – a context not at all dissimilar to a playground. Rather than suppress these concepts and pretend they don’t exist, GTAIII highlights each of them and allows the player to engage with them in a way and in a world that allows for a much more nuanced understanding of violence than most detractors would ever give the game credit for.

Again, I’m not trying to make a case that GTAIII or any of its successors make as powerful or poignant a point that, say, a Goodfellas or a Sopranos might make about the nature of crime and human nature. But it’s absolutely integral to our understanding of its legacy that we recognize how much GTAIII accomplished by bringing video games into a much more mature and complex arena of critical thought and analysis. “Mature gaming” doesn’t just mean nudity or blood: it means games that broach subject matter that is relevant to adults, and that allow them to engage with that subject matter through the mode of play.

Although GTAIII absolutely has its fair share of shallow, mindless entertainment, its structure and gameplay paved the way for games to contend with crime and violence on a much deeper and thought-provoking level. This, I think, is as important a part of its lasting cultural influence as anything else.

BONUS LEVEL: Satire, Bloody Satire

At the time of GTAIII’s release, satire as a comedic and artistic mode of expression was beginning to be utilized more and more frequently in the medium of video games. By that point, gaming had been around long enough, was popular enough, and had accumulated enough diversity of content for developers to begin subverting traditional narratives, styles, and tones to explore and criticize the nature of their art form, as well as other aspects of the culture at large. However, then and now, I think that GTA is one of the few series to effectively satirize the nature (and celebration) of violence in pop culture — both within its own context of video games, and beyond.

What’s especially fascinating is the progression of this satire, and how slowly but surely it evolves to being not just a facet of GTA’s style and tone, but also one of its most central characteristics. Not to extrapolate too much, but I don’t think that it’s too far off-the-mark to hypothesize that GTA’s growing infatuation with satirizing pop culture directly reflects the series’ own rising infamy and place in public discussions of morality. In the wake of GTAIII’s controversies, Vice City seemed to turn the microscope back on its forebears by being more overt in borrowing from its cinematic influences, most notably Scarface. Through liberal doses of fun 80’s nostalgia and the symbolic legitimization from casting the Goodfella himself, Ray Liotta, to voice its protagonist, Vice City suggested that, if there’s a place in the pop culture canon for Scorsese and De Palma, then there’s room for violent video games, too.

But satire really took center stage when GTAIV, arguably the darkest and most cynical title in the series to date, rolled around. Following the many tribulations of recent immigrant Niko Bellic, GTAIV painted a portrait of Liberty City far more treacherous than what we see in GTAIII, where the protagonist is the one most frequently betrayed, the mythic American opportunity is almost always bought in blood, and where, no matter what, the endgame sees at least one central character dead due to the direct choice of the player. In contrast to the more cartoonish realm of GTAIII, Nico’s story depicts a culture obsessed with violence and crime as a cyclical dead end, where every success brings a greater loss, and every death begets more killing. In turn, the player is forced to reexamine their own relationship to the game, and their own role as a consumer of violent entertainment.

Although GTAV would further the series’ satirical streak with a topical take on the superficialities of entertainment culture in the social media age, for my money, it is GTAIV that digs the deepest towards the nature of violence in American popular culture and gets the most mileage out of its use of satire.

VERDICT: Well, You’ve Probably Figured It Out By Now

Well, I guess for my first go-round at this canon business I ended up just making a full-throated defense for a game that probably didn’t need a full-throated defense to begin with. But let the record show here and anywhere else that Grand Theft Auto III is now and forever an indisputable video-game classic. Featuring a compelling neo-noir narrative packed with memorable characters and vibrant gangs, GTAIII brought a whole new style of third-person shooter into existence with its deeply detailed open-world, extensive collection of vehicles and weapons, and liberal doses of murderous mayhem. But the true staying power of the game comes from its sardonic and topical sense of humor combined with its radical approach to depictions of violence in video games. It truly brought about a new era in video gaming, and would go on to be referenced, awarded, cloned, and discussed innumerable times in the years following its release.

With all that in mind, I hereby sentence GTAIII to life in the video game canon, with zero chance of parole.