The following is an entry in The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake, a series that analyzes how and why the remake of Final Fantasy VII is a landmark innovation in both Final Fantasy and video-game storytelling more broadly. Read the series’ mission statement here.

I live in fear that my schedule will outgrow my favorite video games.

As someone who plays video games the way that others read novels, I’ve gravitated over the years to the sagas of Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs), rightly known for rich worlds, intricate plots, and literary themes. The interactive storytelling of these games has largely formed the basis for With a Terrible Fate, offering a menagerie of narrative effects that aren’t at home in any other medium.

Yet as I’ve gotten older and my life has taken on more dimensions beyond gaming, I’ve found that these stories take materially longer to complete—and not in the same way that a novel can require commitment to finish. I’ve come to believe that the traditional structure of JRPG stories makes them qualitatively more onerous to complete than a comparable story in a novel or film. This creates the potential for a tragic kind of irony: as gamers grow older and hungrier for more sophisticated stories, many of the best stories in the medium seem to have too high a barrier to entry to merit experiencing.

In the face of the practical hurdles to regularly playing JRPGs, Final Fantasy VII Remake has proposed an alternative model for equally robust storytelling more easily accessible for adult gamers: a more succinct mode of storytelling that uses replay mechanics and a sense of real-time urgency to turn an incomplete plot into something thematically richer than games that are twice as long. I begin by identifying three aspects of traditional JRPG storytelling that make them challenging to engage with as gamers get older: length of plot, discontinuity of player action, and opacity of games’ optional content. Then, I show how the timeline, theming, and replay structure of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s story overcome these difficulties—including a new interpretation of the narrative value of the game’s postgame content, which I call “The Chadley Interpretation.” While the structure of Final Fantasy VII Remake may initially seem too esoteric to be easily replicable in other JRPGs, I ultimately argue that this alternative approach to JRPG storytelling is more accommodating than it appears, giving us reason to be excited for what comes next in INTERmission and beyond.

(Spoiler warning for Final Fantasy VII Remake, Final Fantasy VII, Final Fantasy X, Final Fantasy XIII-2, BioShock, Xenoblade Chronicles 2, Code Vein, Tales of Berseria, Tales of Vesperia, Dark Souls II, and The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask.)

Three Challenges for Traditional JRPG Storytelling

JRPGs tell some of the best stories in gaming, but the structure of those stories makes it hard for those with limited time to engage with them. Ultimately, these structural issues emanate from two factors: the density of events in JRPGs’ plots, and the dependency of those plots on the agency of players.

To be clear before we begin, I’m not arguing that there’s anything intrinsically faulty about typical JRPG stories. On the contrary: many of the stories I’ve found most remarkable in the medium of video games are this sort of JRPG, which is why, while I continue to regularly play such games, I find it disappointing that core elements of their storytelling make it less practically feasible to play them as life goes on, players grow up, and other obligations intercede. It’s in that spirit, therefore, that I offer Final Fantasy VII Remake as a case for a different storytelling model that should supplement, rather than supplant, the traditional JRPG model we’ll now consider.

JRPG Storytelling through Long Plots

No matter how you measure them, JRPGs are long.

Several years ago, video game analyst Peter Finn shared with me that he was frustrated with how long these games took to complete, saddened that he simply didn’t have enough time for them as he entered adulthood. Armed with my perspective on the literary value of games, I was quick to point out that adults make time for great, long novels, such as War and Peace; why, then, should avid readers of video games commit any less time to them?

It turns out that my intuitive comparison got the data completely wrong. On average, the great literature of JRPGs takes significantly longer to complete than the great literature of novels; the story of Persona 5, for instance, takes roughly two and a half times as long to experience as the story of War and Peace.[1]

A sampling of average time to read classic novels and classic JRPG stories; data collected from readinglength.com and howlongtobeat.com.

On average, the stories of JRPGs simply take longer to experience than the stories of novels, let alone the stories of films or plays, which only require a couple of hours. In part, this is because the activity of video games is intrinsically more time-intensive than comparatively passive media—a player needs to discover how to advance a video game’s plot and demonstrate a level of skill in order to advance it, whereas a novel merely requires reading the book’s words in order to access the plot—but it also points to the fact that traditional JRPGs add depth to their storytelling through complex, long plots.

The world map of Spira from Final Fantasy X, underscoring the breadth of societies, history, and global conflicts at play in many traditional JRPGs.

Whatever your favorite JRPG may be, chances are good that it features a large cast of characters involved in a wide range of protracted conflicts straddling multiple nations across an entire fictional world. This is what I mean by a complex, long plot: such a story features a number of simultaneous, interrelated series of events, and the shortest series of events that constitute a complete narrative arc for its main characters—and the expression of a complete theme for its audience (what I’ll call a game’s “minimal plot” below)— is relatively long.

Those requirements of a complete narrative arc and the expression of a complete theme are key to our understanding of why JRPG length can feel so onerous to many players. It’s essential to the concept of story that at least the main characters experience a sequence of events that collectively represents something of thematic value to the person engaging with that story; that’s what makes a story feel complete, and it’s what can make us feel a need to finish a story that leaves us, at its “conclusion,” with characters that haven’t yet experienced a full sequence of events expressing a theme (for instance, stories like Final Fantasy XIII-2 that end on a “To Be Continued” screen).[2]

This is why it can feel like such an investment to decide to engage with a long story: unless and until you get through the entire plot, you don’t get to experience a complete theme, meaning that you effectively need to commit to completing a marathon or else risk the perils of sunk costs on a plot you fail to finish experiencing. With each additional hour added to the length of a JRPG’s minimal plot, the binary threshold of required investment to derive narrative meaning from the story is raised. And, to say the obvious, there’s no guarantee that a story will be told well, meaning that players also risk investing one hundred hours or more in a JRPG’s story only to find that its conclusion doesn’t actually impart the thematic meaning they expected, in which case they might feel as though they wasted their time even if they did diligently play through the entire plot.

The Discontinuity of a JRPG Player’s Maxims

The case for JRPGs being inaccessible for adult players goes deeper than mere length, though. Even in the case of comparing a JRPG and novel of equal length, the interactivity of video games would make the JRPG, all else being equal, a more challenging kind of story for an audience to engage with over a long, intermittent period of time—as is the case for many of us who fit video-game stories into sporadic pockets of time that open up in our schedules.

Ideally, the interactivity of a JRPG isn’t the same as a reader interacting with a novel by turning a book’s pages, nor is it the same as mindlessly pressing the buttons of a controller in order to make an avatar execute certain actions. The player of a JRPG, and of a video-game story more generally, acts on maxims: rather than merely committing an action indifferently, this means that she chooses to commit certain actions based on certain reasons with the goal of bringing about certain ends. We recognize the goals of a game’s avatar, the stakes of the story, the nature of its world, and so on, and we subsequently decide to provide certain inputs in order to promote the ends that we desire.

This matters because many of the most innovative video-game stories essentially refer to, and make meaning out of, those maxims. To name just a few examples:

- The revelation in BioShock that the avatar (Jack) is a mind-controlled puppet, controlled by other characters, is jarring because it undermines the player’s assumption that the avatar was a tool for effectively implementing her own maxims.

- The player is able to cultivate her role as a metaphysical determinant of Xenoblade Chronicles 2’s world because the story makes meaning out of the player’s persistent choice to change the world as her capacity to do so increases.

- The pattern of decision-making cultivated in the player of Code Vein shapes the player into a vampiric presence in the story, mirroring the role of one of its main antagonists.

Because player agency is a key feature of what makes video-game storytelling special, the lion’s share of my analysis on With a Terrible Fate focuses on interpreting the narrative meaning conferred in this way upon sets of player maxims. That video games can tell stories in this way is groundbreaking, but it also presents a challenge to games that are played over a long period of time in short intervals.

The player who breaks up a fifty- or seventy-hour JRPG into play sessions of just a couple of hours at a time can find it challenging to keep track of her own maxims. It can be challenging enough to keep track of the many events in a JRPG’s plot, on account of which many modern JRPGs offer easy-to-access synopses of the story so far within their user interfaces: it’s a further, potentially more challenging task for players to keep track of the reasons on the basis of which they chose to undertake actions over the course of a JRPG’s story.

Many modern JRPGs attempt to mitigate the challenge of long playthroughs with easily accessible synopses of the plot from the beginning of the game up to the current moment in a player’s journey, as we see in the case of Tales of Berseria here—but these synopses typically can’t remind the player of the maxims according to which she’s acted throughout the game.

As I mentioned in my analysis of Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch, I spent a period of months away from that game before finally deciding to play through its latter two thirds. When this happens, even if you can reconstruct the early events of the time, it’s hard to authentically recall why you chose to act in the way you did, and so it can be hard to construct an accurate picture of the role the game’s story is attributing to its player. Over a long enough period of time away from a game, the player herself may find that she has grown or changed sufficiently that her latter choices in the game can’t even rightly be attributed to the same agent who played the earlier stages of the game.

This is a particularly thorny hurdle for the many JRPGs that, in my view, feature endings that are difficult to understand without a comprehensive analysis of the player’s role in the story.[3] In cases like Xenoblade Chronicles, NieR, or even Okami, a deeply impactful and narratively consonant ending can be rendered totally inscrutable without a firm grasp of the role the game has defined for the player, and that grasp can be difficult to achieve without sustained focus and reflection on one’s decision-making over the course of the entire story.

The Opaque Storytelling Value of JRPGs’ Optional Content

So far, we’ve considered the challenges of experiencing a JRPG’s minimal plot under the time constraints of an adult gamer’s schedule; the equation gets even more complex when we factor in the events of a JRPG that a player may choose to enact but needn’t enact in order to complete the JRPG’s minimal plot. We often refer to some of these events as “sidequests,” but in our current analysis, we can be broader than that term usually implies, referring to anything from an optional boss to an optional collectible item to an optional quest with characters that don’t otherwise appear in a game’s plot.

Here’s the problem: as the diversity of optional content I just gestured at suggests, these sorts of events can sometimes have a tremendously significant impact on a game’s story, and they can sometimes have virtually no influence on the story. The original Final Fantasy VII is a prime example of the former, with two totally optional party members, Vincent and Yuffie (the latter of whom players of Remake are currently meeting in a remade Midgar for the first time!), who totally change the dynamics of the core group of protagonists, emanating out to impact the overall story (think of the impact of confronting Hojo with Vincent versus without him, for example). Yet other events in Final Fantasy VII are optional with little material story impact; discovering and exploring the Ancient Forest, for instance, allows the party to acquire a range of valuable items, but the acquisition of those items doesn’t significantly recontextualize any of the story beyond the events within that forest.[4]

Discovering Yuffie for the first time in Final Fantasy VII is a totally missable event—but making its narrative impact obvious ahead of time would undermine that very impact.

If I’m an adult playing a JRPG like Final Fantasy VII and I’m looking to play its story as efficiently as possible, then it stands to reason that I’ll aim to engage only with whatever optional content impacts its story—but merely by playing through the game, it can be virtually impossible to know ahead of time whether optional content will or won’t impact the story. Nor should it be possible to know this ahead of time: the stories of many video games, along with the roles they define for their players, depend on the player discovering certain aspects about the world organically (this is especially salient in the case of games with optional final bosses or endings that only transpire under certain conditions, like Tales of Vesperia or Dark Souls II: Scholar of the First Sin). So, I now find myself in a trilemma:

- either I have to play all of the game’s optional content at the risk of missing story-influencing events, in which case I add significantly to a game’s length and exacerbate the first problem we discussed

- or, I opt to avoid all of the game’s optional content, in which case I risk significant gaps in my understanding of the overall story

- or, I get information from an external source (e.g., a friend, a guide) about what optional content matters to the story and what doesn’t, undermining the narrative impact of stories that depend on the organic discovery of an optional event’s narrative impact

More fraught still is the tension this can introduce to the experience of playing a JRPG alongside someone else, as many of us may want to as we grow up and invite everyone from parents to partners to children into our love of gaming. If we watch a film with someone else, there’s a simple and dependable 1:1 correspondence between the content on the screen and the substance of the story we’re experiencing. In contrast, if we’re playing a JRPG with someone in order to share in the story, it runs the risk of creating undue stress to undertake a sidequest and not know whether it will end up making a difference to the story, making some players (me, at least!) anxious about potentially wasting the time of onlookers by adding story-inert playtime to an experience that can already be one hundred hours long.

Final Fantasy VII Remake’s Model for the Adult JRPG

The full remake of one segment of the plot of a classic JRPG that has spanned multiple media and spawned numerous spinoffs is hardly the venue where you’d expect to find a new model for succinct, adult-accessible video-game storytelling; against all odds, I want to suggest to you, that’s exactly what Final Fantasy VII Remake accomplished.

Where typical JRPGs deploy long plots and player agency in ways that create a high barrier to entry, Final Fantasy VII Remake’s seemingly disparate elements unite to show how JRPG stories can be equally rich by relying less on long, dense plots and more on modes of replay and supplementary engagement that allow players to delve further into a game’s story without requiring that they do so in order to get anything out of the game at all.

Player Urgency through a Well-Defined Timeline

It’s impossible for a video game to prevent a player’s life from getting in the way of her completing it in a timely manner, but Final Fantasy VII Remake shows that the way in which a video game’s story represents time can radically influence a player’s incentive to complete it in a timely manner.

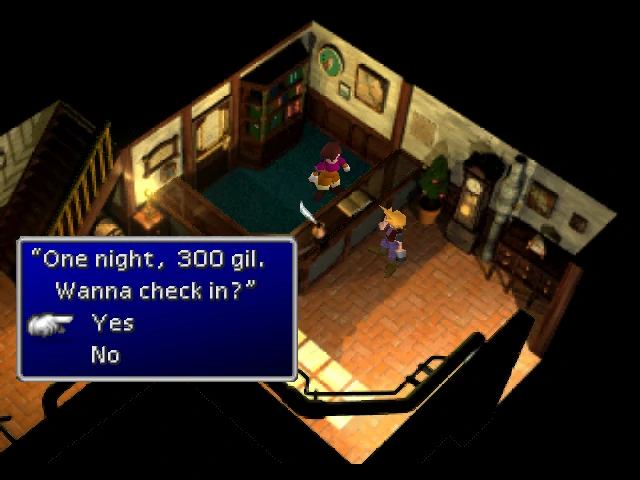

Kalm’s inn in Final Fantasy VII.

Beyond the mere amount of time needed to complete a JRPG and the density of events in minimal JRPG plots, I think that players experience JRPG plots as long because, in many cases, their stories take an ill-defined, long amount of time within the fiction. Entire wars and worldwide journeys transpire between the beginning and end of the game; what’s more, the length of plots can be indefinitely extended because many JRPGs feature inns where avatars and parties can recover health and abilities by sleeping overnight—a resting mechanic that the player can use as many times as she wants, adding as many days to the game’s plot as she desires. With a plot that can stretch on over any amount of time, there’s very little incentive for a player to be timely in completing it, even with archvillains nominally threatening the fate of the world.

In contrast, while the plot of Final Fantasy VII Remake doesn’t feature anything like a real-time clock, it takes place within a well-defined, six-day timeframe.

- Day 1: the game begins with the bombing of Mako Reactor 1 and Cloud visiting the Sector 7 Slums before retiring for the night

- Day 2: Cloud works in the Sector 7 Slums and travels with Jessie to the Plate in the evening to get a new blasting agent, doing battle with Roche along the way

- Day 3: Cloud & co. encounter the Whispers for the first time, infiltrate Mako Reactor 5, and confront the Airbuster after Shinra springs its trap on them, leading Cloud to fall off the Plate into the Sector 5 Church

- Day 4: Cloud wakes up in the Church, meets Aerith, works in the Sector 5 Slums, and sleeps at Aerith’s house, traveling through Wall Market, the sewers, and the Train Graveyard back to Sector 7 that night to see the Plate collapse and Aerith get captured by Shinra, ultimately returning to Aerith’s home that same night

- Day 5: Cloud & co. travel through the sewers with Leslie to find a way to reach the Plates, and they tie up loose ends helping people in the Slums before confronting Shinra at Shinra HQ, ultimately facing the Whispers and Sephiroth at Destiny’s Crossroads

- Day 6: the end of the game sees Cloud & co. leaving Midgar at the dawn of a new day

While Final Fantasy VII Remake retains the resting mechanic common to JRPGs, it only allows Cloud & co. to rest in this way on benches, a transient kind of recovery that doesn’t extend the game’s story into a new day.

Cloud resting on a bench, a decidedly more fleeting mode of rest than spending a night at an inn.

This fixed timeline has two effects that are relevant to the story’s accessibility for a busy player:

- It gives the player a sense that the story cannot be postponed. All else being equal, it is easier as a player to disengage and extend a game’s story over a long period of real-world time if the fiction itself licenses indefinite extension of a quest’s duration, as is the case in JRPGs with fictionally long campaigns and inn mechanics. When a story is confined to a countable, fixed series of days in a single location, it feels less permissible within the fiction for the player to defer completion of the story, incentivizing her, to the extent feasible, to exert her fictional agency in a single, sustained burst without long breaks.

- It provides clear context for the narrative value of optional content in the game’s minimal plot. Most of the optional content in Final Fantasy VII Remake is clearly identified as supplemental opportunities to help people in Midgar by performing odd jobs, a context that suggests to players that these sidequests will help to improve the game’s world and Cloud’s relationship with it without materially impacting the overall plot.[5] This context alone, though, isn’t enough to make certain that these sidequests won’t change the course of the story: as a contrastive case, think of Majora’s Mask’s Anju and Kafei sidequest, which starts off as an unassuming case of helping two people in a town but ends up occupying an entire three-day cycle of the game’s time-looped world; in order for a player to be confident that “odd job”-style optional content won’t inadvertently alter the course of a story, it’s critical that the player have reason to believe that a game’s plot is proceeding according to a schedule that can’t be interrupted or radically altered by such content. This isn’t the case in Majora’s Mask because the player understands that Link can play the Song of Time to reset the world’s schedule ad infinitum; in Final Fantasy VII Remake, on the other hand, the apparently clear, rigid, finite flow of time goes a long way toward indicating to players that these sidequests constitute content that they may safely opt out of without radically altering their understanding of the overall plot—and it indicates this while preserving the potential for the player to authentically discover these sidequests in a way undermined by guides that more explicitly list available sidequests and their ultimate outcomes.

Barret’s quiet, sincere expression of a desire to help the citizens of the slums sets the context for the optional content of the game available immediately before the gang’s final assault on Shinra.

This structuring of time in Final Fantasy VII Remake, therefore, mitigates two of the accessibility problems we identified with the traditional JRPG: the sense of urgency and obligation it instills in the player counterbalances the risk of discontinuity in a player’s maxims, and the contextualization of optional content within the plot’s fixed timetable makes the narrative impact (or lack thereof) of that optional content more transparent than opaque.

Representing a Complete Theme with an Incomplete Plot

The way in which Final Fantasy VII Remake treats time goes a great distance toward making JRPG stories more accessible to adult players, but it leaves the apparently least soluble problem untouched: how do you make the long plots of JRPGs more digestible without simply making them shorter—and, therefore, less sophisticated?

This may be Final Fantasy VII Remake’s greatest and trickiest achievement when it comes to JRPG accessibility: it’s a case study in how a plot that is not only short but also incomplete can bring about unique thematic meaning as rich as the themes in any JRPG with a longer plot. It achieves this through two means: (1) making one of its core themes essentially refer to the incompleteness of its plot, and (2) presenting a replay experience that adds more sophistication to that same theme, making more narrative meaning available to players willing to spend more time with the game without requiring that players spend that long with the game in order to derive any thematic meaning whatsoever from it.

The way in which Final Fantasy VII Remake represents a complete theme through an incomplete plot was the primary focus of my article “Final Fantasy VII Remake is Completely Incomplete,” from a few months ago. There, I argued that the precise sequence of the remake’s final act—(1) the player’s confrontation with Whisper Harbinger, representing the annihilation of her own expectations for the plot, followed by (2) the party’s confrontation with Sephiroth, with his premature defeat unexpectedly negating his antagonistic status, followed by (3) the non-interactive battle between Cloud and Sephiroth at the Edge of Creation, liberating Cloud and Sephiroth from the concept of story and the influence of the player—collectively tells an alarmingly thoroughgoing story about the theme of radical freedom, according to which the characters of Final Fantasy VII Remake are able to liberate themselves, with the help of the player, from being characters in a story at all.[6]

The manner in which Final Fantasy VII Remake’s finale undoes traditional frameworks of meaning around its characters grants them the exact kind of freedom that Aerith foretells at Destiny’s Crossroads. This freedom is boundless in that the characters, after the events of the final confrontation against Sephiroth, are able to act outside the construct of a plot. This freedom is terrifying in the sense that it puts those characters—characters from one of the most teleological, fate-driven worlds in modern storytelling—in the position of acting on their own maxims, an ability which, by definition, puts their intentions beyond the realm of that which the player of Remake can know at Remake’s conclusion.

This is an old trick of many masterful storytellers: to tell a great story within a certain constraint, make the story about that constraint. That’s allowed Hidetaka Miyazaki to tell compelling stories in Dark Souls and Bloodborne DLC whose themes reflect the perverse nature of wanting games to tell complete stories yet also wanting extensions of those stories; it’s allowed Italo Calvino to write novellas like If on a winter’s night a traveler…, meditating on the limitations of authorial intent in a medium that inherently separates a work’s interpretation from its creator. To tell a thematically meaningful JRPG with a comparatively short plot, Final Fantasy VII Remake tells us, simply tell one whose core theme essentially depends on the brevity of that plot.

One of the remarkable opportunities for this mode of JRPG storytelling is that, if the follow-up Final Fantasy VII Remake games (and DLC, including INTERmission!) succeed in telling stories that (1) are similarly thematically compelling on their own terms and (2) integrate with one another to convey further-reaching, equally coherent themes, then the series will have shown us how JRPGs, when broken down into bite-sized segments, can tell short, accessible stories while also representing much longer, traditional plots over the entirety of the series. We’ll have to wait for the rest of the games before we can render a verdict on that front; as it stands, we can only say so far that Final Fantasy VII Remake tells a thematically compelling, succinct, self-contained JRPG story while also setting up a plethora of interesting places for the plot to go thereafter.

Thematic Layering and “The Chadley Interpretation” of Final Fantasy VII Remake

We can grant that Final Fantasy VII Remake tells a thematically complete story with an interrupted plot—we can even grant that it may ultimately additionally serve as one puzzle piece in a thematically consonant, longer series of games with one continuous plot—and we can still worry that this game, on its own terms, pales in storytelling value to other JRPGs because it doesn’t have the same density of plot with which to represent especially elaborate and nuanced themes.

I think the theme of radical freedom I’ve outlined here and in my previous analysis is plenty compelling on its own terms, but this is still a reasonable concern—and it turns out that it points to yet another way in which Final Fantasy VII Remake offers a more accessible mode of narrative depth than the traditional JRPG: rather than expressing a core theme over one, long plot, it provides progressively richer layers to its core theme through the act of replaying the plot. Analyzing the game in this way opens the path to a new interpretation I’ll call The Chadley Interpretation, viewing Final Fantasy VII Remake as a vehicle for using player agency to free the story’s characters not just from the story, but also from their own limitations.

The game tutorial’s description of Hard Mode, a new difficulty level available after completing the plot once.

After completing the plot of Final Fantasy VII Remake once, Hard Mode is unlocked along with Chapter Selection. Together, these two modalities offer:

- Twice as much experience and three times as many ability points from battle, making it radically easier to make Cloud and the gang stronger, in exchange for restrictions on item usage and health restoration

- The ability to play the game’s chapters in any order at will, making different choices that cascade to subsequent chapters

- New challenges in the Combat Simulator, allowing the player to defeat new virtual opponents and reach the conclusion of Chadley’s storyline

The player seeking to collect all the trophies from the game needs to complete a variety of tasks only available through these modalities, such as the completion of all chapters in Hard Mode, the completion of all Combat Simulator challenges, and the acquisition of all dresses for Cloud, Tifa, and Aerith in Wall Market, only possible by making different choices through multiple replays of certain chapters in the game.

Superficially, this seems like a fairly standard way for a modern video game to offer its player a further, optional challenge upon completing its story; the game’s tutorial section, shown above, even emphasizes that “the story remains the same” when the player revisits various chapters through Chapter Selection. However, this description belies the subtle way in which these further challenges add new, even more empowering and narratively rich dimensions to the game’s central theme of radical freedom—and the cipher to understanding these new dimensions is a revelation, only available in Hard Mode, about the unassuming side character, Shinra “intern” Chadley.

Initially, Chadley represents himself as a lowly intern who wants to use Cloud for field research to create new materia for use in subterfuge against Shinra. Eventually, he gives Cloud & co. access to a Combat Simulator that allows them to do battle against virtual representations of soldiers, machines, and mythical creatures approximated from historical data (e.g., Shiva, Ifrit, Bahamut).

In the minimal plot of Final Fantasy VII Remake, my above remarks about the game’s optional content hold true for Chadley’s tasks: Cloud can elect to help him with his research and gain powerful materia in the process, but this research doesn’t materially alter the substance of the story. In Hard Mode, however, should the player challenge the new Combat Simulator gauntlets and conquer them all, Chadley reveals his true identity and consequently provides a richer way to understand the game’s core themes.

It turns out that Chadley is not a human but rather “a cyborg created to serve as Hojo’s assistant,” with superhuman knowledge but no agency beyond the will of Hojo. Chadley was able to use Cloud—whom he describes as “a subject with infinite potential”—to continue obeying his research directives while simultaneously learning, through Cloud’s combat data, how to upgrade himself to become independent of Hojo.

That sounds familiar: Chadley, a character bound to the will of another, was able to undergo a carefully orchestrated process to liberate himself of that bondage, not unlike the freedom I argued Cloud, Sephiroth, and others achieve through the carefully orchestrated finale of the plot. At first, then, his character seems like a compelling microcosm of the plot’s initial focus on radical freedom. I think Chadley’s real narrative value goes further, though: in a reveal only accessible within the context of Hard Mode, he illustrates another layer of the game’s theme of radical freedom, showing players how their replaying the game adds unique richness to the overall story.

Chadley describes Cloud’s final victory, which empowers Chadley’s own liberation, as Cloud having “managed to fully tap into the potential once locked within [him],” potential that Chadley has called “infinite.” This evokes the constant Final Fantasy VII motif of Limit Breaks: those actions that allow characters to exceed the logical bounds of their own abilities in order to achieve exceptional feats (feats, for instance, like defeating Sephiroth with the Omnislash Limit Break in the original Final Fantasy VII). Of course, the notion of characters becoming free from their own story also fits with the notion of surpassing one’s limitations—but Chadley’s remarks are most valuable in drawing parallels between Cloud’s journey with the Combat Simulator and the player’s journey in Hard Mode and Chapter Selection.

Cloud deploying the Ascension Limit Break inside the Combat Simulator of Final Fantasy VII Remake.

The player who chooses to revisit the game through Hard Mode and Chapter Selection after completing the plot gains the ability to break through the limits of the plot across multiple dimensions:

- She can move in and out of chapters at will in any order, collecting items and making progress that persists despite it not happening in the “proper order” of the plot’s logic

- Like someone manipulating a Combat Simulator, she can raise the difficulty level of Cloud and the gang’s encounters in order to give them more experience—experience that literally surpasses the highest level of ability the plot is able to attribute to them, for all experience earned beyond Level 50

- She can explore more possible versions of the plot than one possibly could in a single journey through the world, accessing different outfits for the climax of the Wall Market subplot, different resolution scenes between Cloud and other party members, and so on

All of this happens on the path to the player completing everything possible in Final Fantasy VII Remake and unlocking the “Master of Fate” platinum trophy: a trophy that, I’ve argued, represents not only the player’s ability to alter the expected outcomes of the game’s plot but also the player’s inability to alter the essential aspects and relationships of characters in the story. By achieving everything possible in the game, she doesn’t unlock some “secret ending” or otherwise gain access to some new events beyond the conclusion of the game’s minimal plot: instead, she empowers the characters to reach their full potential, beyond the limits of what is possible for them within any single instance of the game’s plot. This presents a novel way to interpret not only Final Fantasy VII Remake’s core theme of freedom, but also how that theme evolves as the player pushes herself beyond the limits of a single playthrough:

The Chadley Interpretation: a single, minimal playthrough of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s plot represents the theme of an audience recognizing the limitations of characters trapped within a story and freeing them from that story; a complete playthrough of Final Fantasy VII Remake, including Hard Mode, adds to that theme the audience recognizing the intrinsic value of the characters trapped within a story and using the audience’s own privileged position to reach beyond the story’s limits and empower the characters to be more within the story than the story itself initially allowed them to be.

It’s the player’s recognition of the characters’ capacity for freedom and identity that empowers the player to use her enhanced “postgame” agency to make them more powerful, with more robust relationships, than was conceivable in the initial plot. This further ties the notion of character liberation, too, to the concept of intrinsic value that I argued at the end of my last analysis is essential to the broader Final Fantasy VII corpus.

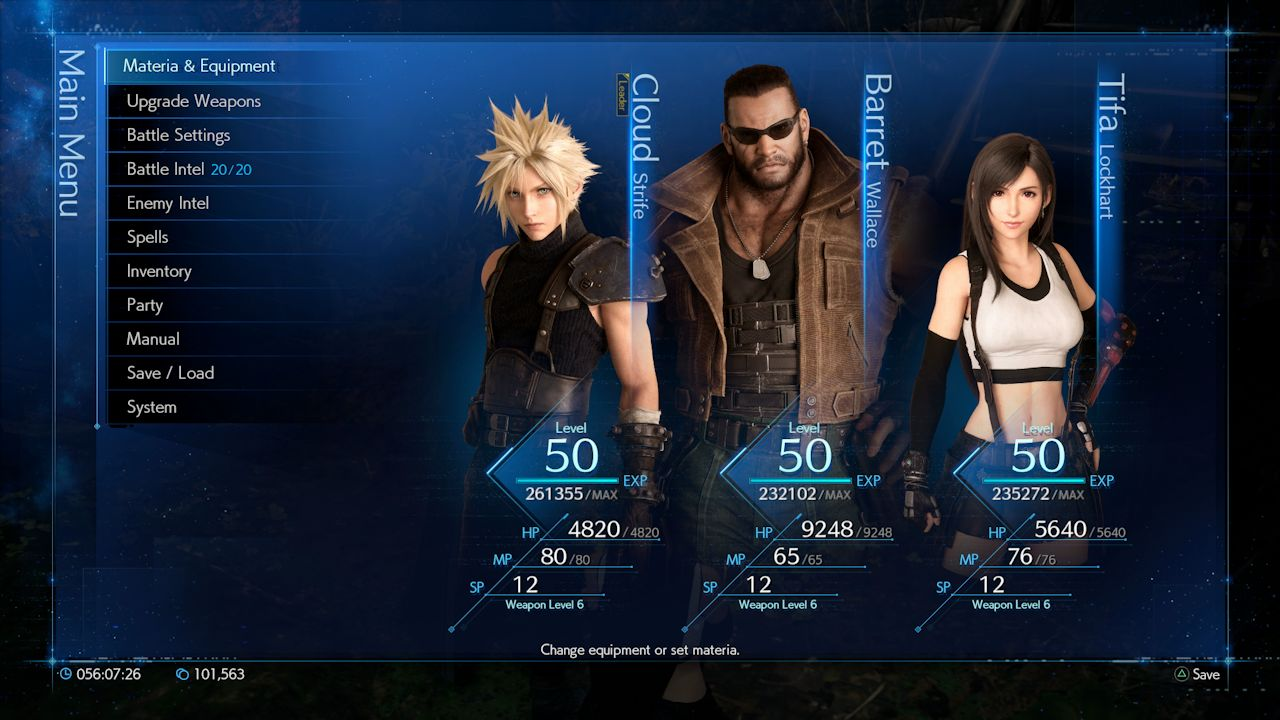

Cloud, Barret, and Tifa: still gaining experience despite having reached the story’s preconceived limit of their possible level.

Stepping back, we can see that The Chadley Interpretation shows us something surprising about Final Fantasy VII Remake’s storytelling that we can extend to JRPG storytelling more broadly: the dynamics of the JRPG’s postgame, or the actions available to a player after completing its minimal complete plot, can enrich the plot’s core themes by adding a further interpretive layer to those themes, without thereby making the game’s minimal plot feel like an unfinished or worthless story.

That’s a big deal because it allows JRPGs to have incredibly sophisticated storytelling themes without introducing an enormous plot as a binary threshold for accessing those themes at all. If you’re an adult gamer with limited time and you play through the credits of Final Fantasy VII Remake once and then put it down, you get a full, great story with compelling themes—and you don’t need to commit 80 hours of your life to the game in the process. Yet if you want to go deeper and get even more value out of the story, you can replay that same plot with new abilities, learn the truth about Chadley, and, in the process, learn something new and richer about the events from which you already derived value on your first playthrough.

From Final Fantasy VII Remake to JRPG Storytelling Remake

Final Fantasy VII Remake’s orchestration of narrative time, form-conscious theming, and thematic layering through replay dynamics presents a different mode of JRPG storytelling that overcomes what I see as the most pressing barriers to continued adult engagement in the medium. It’s fair, though, to raise the question of just how much this form of storytelling can be generalized. Final Fantasy VII Remake’s minimal plot is relatively succinct, but it also depends on a player’s familiarity and engagement with a whole other JRPG, Final Fantasy VII; its themes make compelling meaning out of its particular dynamics, but isn’t the idea of liberating characters from their story relatively niche and challenging to replicate in other stories?

These are real challenges to the idea of Final Fantasy VII Remake as a model for future JRPGs, but I don’t think they’re insurmountable challenges. At an abstract level, the key thematic dependency of Remake on the original Final Fantasy VII is just the concept of the player’s role in having enacted and thereby become invested in a plot that is supposed to go a certain way, which they are then made to negate. Plenty of stories begin by recounting legends, lore, or myths that are subsequently challenged; it’s not especially esoteric to imagine a range of JRPG stories that begin in this way with an interactive kind of prophecy, getting the player attached to that prophecy so that her ultimate undermining of it is a real rebellion against and defeat of her own expectations, desires, and narrative authority.

Similarly, while I’ve argued in the past that characters rebelling against their own story isn’t actually all that niche or challenging to relate to, nothing in the more abstract storytelling model of Final Fantasy VII Remake depends on that particular theme in order to function. Remember, the key role of that theme in our analysis here was as a way of making thematic meaning out of a short, abbreviated plot. Plenty of themes can conceivably occupy that role: just imagine a JRPG telling a story about transient dream worlds, ending in a haphazard way in order to represent the theme that whatever meaning we attach to our experiences is fleeting; or, imagine a JRPG interrupting a king’s ascension to the throne at the conclusion of an abbreviated hero’s journey to show the intractability of heroic mindsets. These are toy examples, of course, but they quickly broaden the scope of stories we can imagine fitting into Final Fantasy VII Remake’s model.

This needn’t become the default model for JRPG storytelling, and it needn’t even necessarily become as common as the traditional model. As an adult gamer, though, I feel myself taking the time to do an increasing amount of research about the value of a JRPG before taking the plunge to play it, and I’m genuinely thrilled at the prospect of an alternative that allows me to experience stories that are just as rich with less of a sense of investment in the decision to play them. And, as an avid appreciator of Final Fantasy, this has only made me further amazed at the radical puzzle-box of a game that is Final Fantasy VII Remake.

Here’s hoping they keep up this kind of narrative innovation in INTERmission and beyond.

- Data on average reading times for The Brothers Karamazov, Infinite Jest, and War and Peace sourced from readinglength.com with an assumed reading speed of 250 words per minute. Average time to complete the “main story” of Tales of the Abyss, and Xenoblade Chronicles, and Persona 5 sourced from howlongtobeat.com from user polls. ↑

- What grounds the notion of “the expression of thematic value”? We can rely on our intuitive notion of narrative themes for our current purposes, but I favor Velleman’s model of an emotional cadence for a more foundational explanation: on this view, complete stories represent a complete, natural sequence of emotions organized from a state of arousal to a state of resolution (e.g., from curiosity, to excitement, to suspicion, to fear, to uncertainty). (See J. D. Velleman’s “Narrative Explanation” in The Philosophical Review, 112(1), pp. 1-25.) ↑

- And, to be clear, this role of the player is not identical with the character that is the avatar, so keeping track of the avatar’s character development is not enough. I distinguish between the fictional roles of player and avatar in my “The Role of the Player in Video-Game Fictions.” ↑

- Strictly speaking, of course, events in the main story will change if, for instance, Vincent confronts Sephiroth with the Supershot ST (a weapon acquired in the Ancient Forest) rather than another weapon; the point is that such a change doesn’t materially impact the thematic content or other modes of storytelling impact the game has on its player. ↑

- Here, I’m setting aside the optional content that is not a part of the game’s minimal plot, particularly the battle simulation mission sequence that can only be completed by playing the game more than once, which I analyze below. ↑

- I’m not claiming that radical freedom is the only theme that’s essential to the storytelling of Final Fantasy VII Remake, but it’s one that I find especially salient and especially illuminating with regard to the meaning of the ending and the unique narrative value of replaying the game, as I discuss below. ↑

CONTINUE READING

- The Legacy of Final Fantasy VII Remake series navigation: < “Why Final Fantasy VII Remake’s Church is so Memorable (and How to Analyze It)” |