The following is a chapter in “A Comprehensive Theory of EarthBound,” a series that aims to better understand the storytelling of Shigesato Itoi’s landmark video game. Find the full series here.

“A-wop-bam-aloom-bop-a-wop-bam-boom” [1]

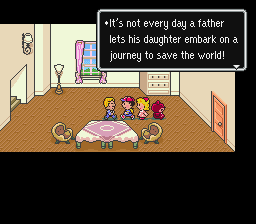

Do your best to enter into the mind of our dear Jeff, boy-wonder of Winters and the most gleefully weakness-rejecting of our heroes, and let his memory float upstream; only recently were we talking about the matrix of father-son relationships that add uncanny psychological credibility to the characterization of EarthBound. Alight gently at one stop that could never enjoy too much of our exegetic attention: that episode in which he and his father, Dr. Andonuts, meet each other again after all those years. Look at the exchange that transpires between them.

How does it make you feel?

Note those feelings, tally them even: a straining outrage at Andonuts’ charmingly befuddled paternal callousness; a briefly unbearable sense of the poignancy of Jeff’s silence; amusement, perhaps, at the stilted comic energy of the ‘exchange’; and, at last, crestfallenness. If you have direct emotional ties to the material, you may even experience something akin to grief.

This moment is a great many things at once, conflicting and combining into one memorable scene of dissonance in a relationship.

This particular moment of dissonance is achieved through writing, both directly through dialogue and indirectly through what EarthBound has established so far of its world–and through its own perspective on that world. Its conflict, both endogenously in content (Jeff vs. his Dad) and exogenously in aesthetic (weight of theme vs. childlike form and design), function as the base colors that blend together to make the distinctive palette of EarthBound.

Have you noticed that music can serve that very same narrative function?

The Harmony of the Good and the Dissonance of the Great

If EarthBound were a symphony, then it would be a symphony written in the Chromatic Scale of Life.

A perfectly good musician knows well the cornerstone of his job: he is the enemy of the “wrong note.” Dissonance so widely connotes a lack of harmony, a dismalness and discord, that its use stretches far beyond music. Oh, no; you’re playing in C Major? You’d better stay away from those black keys, my friend.

That goes for perfectly good musicians. Those musicians who are that much more than “perfectly good,” on the other hand, are masters of the chaos, friends of the dissonance. They may chance closer to the boundaries of the acceptable more often than is strictly advisable; and yet as you watch them do so, the disharmony you dread to anticipate never arrives–or, even if it does, it does not arrive as expected.

This is because, when wielded correctly, even notes that are dissonant can find a whole to which they belong. Where some see incompatibility, others see an unlikely connectedness. As the giant of jazz, Gil Evans, once said, “The only reason one chord could sound wrong is with the next chord. No such thing as a clinker.”

Q: Jazz great Gil Evans, or photo-realistic impression of a more elderly Jeff?

And like we said, EarthBound, even more so than a typical narrative, is all about that dissonance, that seemingly unsuitable juxtaposition of elements, which texturally and narratively brings EarthBound’s entire world to life, influencing our interactive enjoyment and experience of the game.

Music in Earthbound: Dissonance in Eight Notes

EarthBound’s musical personality is built on a compositional device known as accented-dissonance and, where possible, counterpoint. As these were the salad days of the SNES, one of the great leaps forward in console artistry, ’where possible’ is a meaningful modifier.

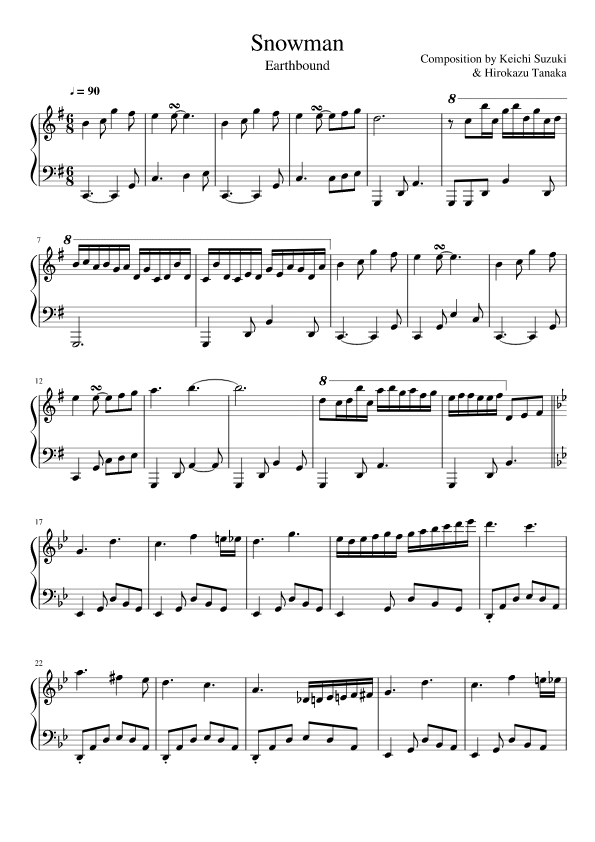

Hard though it may be to believe, EarthBound began development in 1990. Unlike before, the SNES audio chip meant that eight notes were playable simultaneously (each with its own audio track), allowing project composers Keiichi Suzuki and Hirokazu Tanaka to work as they would if they were composing freely for a real-life ensemble. This promised an unprecedented degree of freedom to their musical whims.

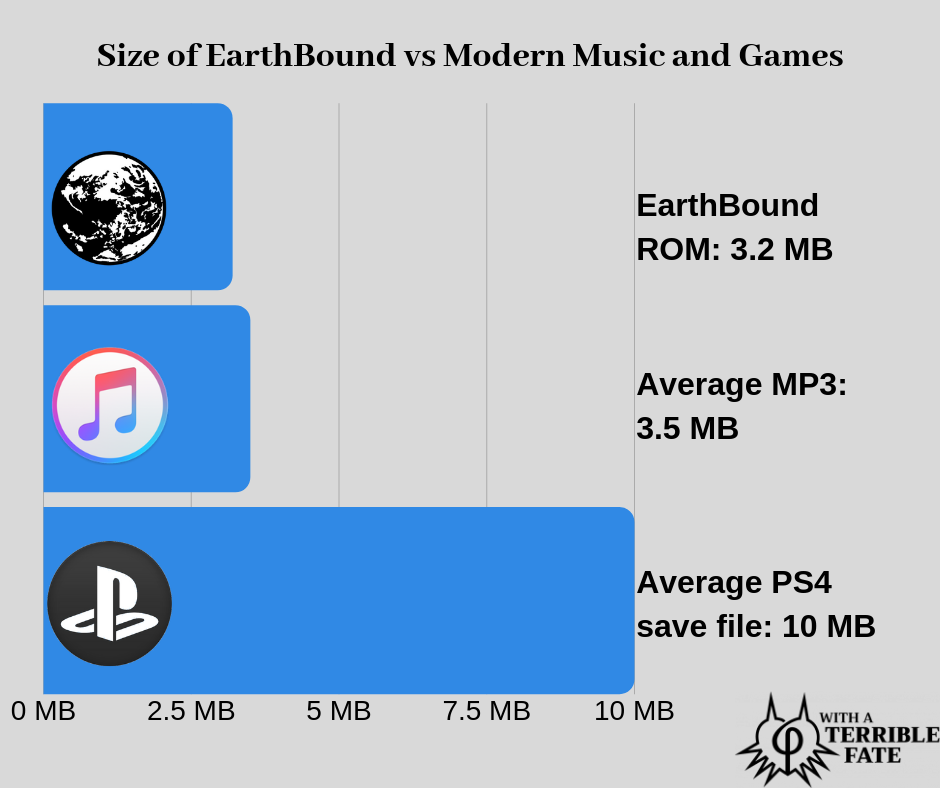

The caveat is that a typical SNES cartridge boasted a total space allowance less than that of a single 3 minute-long MP3 file today:

This explains why EarthBound, typically for the era, privileges smaller pieces; but only the drive and ambitions of these two composers can account for the way in which many pieces nonetheless feel as though they are agitating against their temporal confines, particularly “flagship” works such as the Snowman theme.

Keiichi Suzuki & Hirokazu Tanaka apologize for the tears they will wring from you…

Within these bounds, the sounds of EarthBound form an unprecedented work of scoring artistry. It features daring generic (salsa, dub-reggae) and compositional (sampling) tropes; these kind of genres and methods of constructing music had never before been heard in video-gaming.

Moreover, the richness of harmony afforded by the eight-note allowance dovetails with the performative breakthrough of vibrato-ready MIDI device. As a result, EarthBound has access to a plethora of harmony and to microtonal contour melodically; in the hands of composers as ambitious as Suzuki and Tanaka, games could now be enlivened by their musical settings more fully than ever before.

Judging by the color scheme of its pads, this MIDI keyboard is an EarthBound fan.

A Musical Dictionary

What does all this mean in the context of the game itself: how do these fantastic new elements find a communicable aspect? How does EarthBound turn its limited musical alphabet into a language as robust as actual text?

EarthBound’s dissonant realization of itself is founded in its relation of fact, or realism, to the entirely opposing factor of fancy; we can visualize this more easily if we think of fact and fancy as two opposing colors. We’ve spoken a great deal thus far of horror elements in Earthbound, how they are carried and realized in often ingeniously disguised packages; and while there are a number of instances throughout the game in which music is used to accentuate moments of terror and doubt, the music of EarthBound is more fundamentally allied to the other “side” of the game: its sense of fancy.

Earthbound delights in the amusements and esoteric flourishes of ordinary people; in setting and cast, it is filled with moments that note the splendid in the familiar, and the ways in which the familiar can be and is naturally subverted. In a game that invites imaginative sympathy for its characters, music— especially music of this quality—is a formidable ally. Through that aforementioned plethora of musical elements, each of which constitutes a unique color on an extremely broad tonal palette, we see the characters of the game invested with ineffable qualities that make them seem familiarly human. In fact, EarthBound makes a case for music being the most humanizing aspect of video-game design, that which adds the most “touchable” contour and identifiable shape to characters that might otherwise, left only to the magic of good writing, seem well-molded yet inanimate.

The music of EarthBound is a language unto itself. Let’s make like Pānini immerse ourselves in its tasty grammar now.

The Chromatic Scale of Life – Musical Character

character, n. – The distinctive nature of something

Musical Equivalent – Melody & harmony

We have spoken before of the many micro-conflicts, the “banal villainy,” and the conflict it provokes, latent in the universe of EarthBound; we have spoken likewise of the “aliveness” of this world, without ever considering really the way in which these two elements may be junctioned to one another.

So long as it is moderated, and its instances consciously selected within an overarching structure that performs the necessary mitigations and provides shape, conflict can be of exceedingly high value: it excites the mind, provides color, opens up lanes of insight, and ultimately brings balance. That which alone seems insensible can suddenly be illuminated as part of a whole; what by itself sounds like a “clinker” proves to be just the right chord.

Music demonstrates the value of conflict well. Let’s look at two composers: one who makes little use of harmonic conflict, and one who uses a great deal of it. The great German-British Baroque composer Handel, a master reconciler of music and dramatic flourish, could be described as the former. The German Baroque master Johann Sebastian Bach, and his incomparable flair for continuity and synthesis, can stand in as the latter type of musician.

Listen to the following pieces of music, the first by Handel, the second by Bach.

Both of these compositions are stately slow dances, sarabandes, in 6/8 time. Handel’s work creates drama of its own, but it does so via musical movement in which all the parts are mostly respectful of the principles of key and harmony; were it an RPG, it would be one of exceedingly high quality, but decidedly within the genre’s tradition. I’m fluttering my eyelashes at you, Final Fantasy I.

Listen to the Bach and you may feel the dual effects of a dichotomy that it contains. Within its exterior parts, the bass and the soprano, it establishes a very secure and stable harmonic basis, that which equates roughly to a sense of “niceness,” of affirmative harmony of sound. But look at those internals, the alto and the tenor parts, and you find a whirlwind of chromatics: notes outside of the key. The Bach piece demonstrates the vigor and uniqueness that can be expropriated from conflict, if a masterful enough conductor is in control.

EarthBound’s world operates by the same principle of making conflicting elements coexist, and that goes for its music too. Take, for instance, one of EarthBound’s most delectable and teasingly short pieces, listed on the soundtrack as “I Believe in You,” a piece I have always read as a musical shorthand for the character of Paula. Listen to that extraordinary opening in the harmonic major scale, harmonized so confoundingly it hardly seems to have a tone center—just as Paula herself is of an origin so obscured that calling it muddied would seem too decisive.

Then comes the piece’s response section; being so anchored to E Major, this B section tells us about the character of the music we heard before, and more about the character to which it is attached. The E doesn’t waver as squalls of passing notes wind around it, wavering briefly through a diminished seventh back to that tonic; and so neither does Paula’s essential nature ever threaten to waiver when confronted with the privations of EarthBound’s universe.

Such chaos, such weird wonder and wonderful weirdness: all barely contained, but contained nonetheless, the initial disorder made to seem whole and purposeful. Not only are these conflicting elements made to seem of a piece, but they are also made to tell a story—in this case, a story about Paula, about the hardiness of belief in the face of the uncaring world in which EarthBound’s tale is told, and about the great challenges frequently posed to it. This story reflected in the very structure of the piece: the initial confounding passage, and the way that the response ruthlessly ties it into a harmonic scheme that gives it meaning, a story to tell.

And boy oh boy, do the unconventional musics of EarthBound have stories to tell.

Color and uniqueness of character life in EarthBound is vocalized as much through weird music as it is through writing. Take, for instance, the curious case of Apple Kid. His dedicated theme (which, it’s true, surfaces elsewhere in the game) is one of the most comical: both melody and bassline anarchically muddling their way between major and minor tonalities, while EarthBound’s ubiquitous (and soon to be discussed) alien glissando moans drunkenly in the background. It’s musical slapstick: the aural equivalent of a messy bedroom, a strangely physical little snippet of music that clomps and beavers around like a kid’s imagination, its lack of harmonic respect symbolizing the animated multipotentiality of resolution found in all children.

In short, you remember it once you hear it, and you know Apple Kid better after hearing it. How?

Well, the characters of EarthBound are recognizable through its scriptwriting—even though this is not gaming’s equivalent of Raising Arizona, where characters are permitted incessantly quixotic turns of speech that alienate them from (and so define them against) regular life. But their spirits are given voice by the incidental music, allowing their speech to remain, though distinct, in the quotidian: it allows their spirits to fly through unmitigated dimensions of fancy, while the characters themselves are anchored in the banal.

The marriage of music and dialog amounts to a rich characterization in which neither element is too obstreperous. There is just enough chromatism, enough controlled chaos, to make the final package colorful.

Alien Air – Musical Setting

character, n. – The distinctive nature of something

Musical Equivalent – Ambience

In any medium that makes active use of space, ambient sound is the great unheralded sculptor. Deliberately “formed” music, as heard on a soundtrack, often serves a more overt narrative purpose. Ambience, a circumstantial and often arrhythmic music, is in many ways every bit as apt to convey significant information about location and the way a space is to be experienced by a player.

As it did in so many other regards, EarthBound blazed a trail with the richness and insistence of its ambient noise design. We find ourselves in familiar territory: while Suzuki and Tanaka’s aforementioned expansiveness of tone palette enables more found noises—percussion that sounds like it’s being malleted out of drywall or crunched from gravel, or tunelets purposed from radio static—to be actively integrated into musical settings, pure ambient sound is responsible particularly for setting up EarthBound’s pervasive sense of unreality and unease.

The first in-play “music” we hear in EarthBound is striking in how evocative it proves to be even when handling such an economical ingredients list: in the peace of the night, we are awoken to the dull, discordant portamenti of low-hovering alien spacecraft, accompanied only by the sound of crickets. With the establishment of such a simple ambience, EarthBound’s unique sense of perversion is immediately and eerily established.

These alien ambient sounds, with their inhuman lack of regard for the pitiful human need for harmony, pervade thereafter. Just as Giygas’ unearthly presence is said to distort the perfectly banal and familiar into the aggressive and bizarre, these sounds seem to make an abomination of the poor crickets: their sounds, which should strike us as natural, suddenly become the uneven, workhouse metronome of a dominant extraterrestrial threat, as surely there as they are invisible (much like the crickets themselves).

It seems fine musicians can not only make the unnatural seem right: they can also make the natural seem frighteningly uncanny.

This sonic trope pervades throughout EarthBound. Let despair once again fill your heart as we revisit the “Peaceful Rest Valley” to look at its theme. Your attention is soon led to that horribly flatted fifth that follows the decaying tonic E on the bass, but listen to that waterfall sound effect in the background. Can you feel the merest flicker of a sense of well-being it ignites at first? And then how the water then comes to embody a coursing danger as it is reflected in the music’s unhesitating forward movement and ossified harmony? Pay attention to how, between the two towers of most torturous glissandi in the whole soundtrack, the water, at last, suddenly sounds like it is rising above your head. Notice how the music has become a shorthand for your narrative experience of the valley.

Notice, more broadly, how fundamental those deployments of ambient sound—in synchrony with formal music, or by itself—have been in dictating your emotional reaction while gaming, how thoroughly they have illuminated the terror, wonder, and confusion of EarthBound’s inimitable feeling for space.

It is difficult for a 16-bit game to surefootedly evince horror and fear; shrewd deployment of ambient sound is one way in which EarthBound achieves the effects it is famous for.

Sampling – Music as Allusion

allusion, n. – An expression designed to call something to mind without mentioning it explicitly

Musical Equivalent – Sampling

The seamless incorporation of sampled musical material, and the economy with which short motifs of sampled material are brandished, affirm everything consistently exalted about EarthBound and its artistry. Take, for instance, the theme to “The Cliff That Time Forgot,” sampled from the first three notes of The Beatles’ 1967 recording of “All You Need is Love,” where the notes were themselves a sort of “sample” from the main theme of “La Marseillaise.”

For one, the piece is a thoroughly ingenious extension of EarthBound’s perennial Beatles fixation, whose allusions obscure and more obscure still lend homely charm to the game’s foundational layers of cuteness.

And yet, at the Cliff That Time Forgot, the sample is handled in a way that is extraordinarily transformative, harmonized essentially with the deafening, unnatural silence between each modulated blast of the trumpet line. In a stretch of the game in which play is increasingly indebted to the Horn of Life inventory item, here we have an approximation of, and so an allusion to, the Horn’s own sound: triumphal, sublime—in a sense that is neither joyful nor despairing, completely above human emotional concern—and, in that lack of harmony/rhythm and comfort in silence, disdainful of any context that might give a regular person clues as to its celestial meaning.

All of this, harvested from a mere three sampled notes.

Finally, it comes to serve as a sort of fanfare for Ness and friends’ most stunning act of heroism at the cliff’s edge, one more or less unsurpassed in its noble willingness to sacrifice in video-gaming. Might I be struck down if I spoil it for you.

Beyond circular, ironic allusion to another recognizable, banal object (in this case, the lore of the Beatles), the sampling, via the way it is treated, takes on a more direct power of allusion by referring to the innermost feelings of our characters, together with the reality of their situation, and deepening our impressions of them.

And this is true as a whole of music as an attendant feature of video-gaming. We cannot see music; it cannot demonstrate things literally. So instead, it can be utilized to prize the unspoken, the unspeakable, the subtle, and the concealed from the overt developments in action seen and dialogue entertained. Sampling, fundamentally a feature of postmodern art, has the power to deepen the emotive value that is derived thereby; by appealing via allusion not only to what is held within the depths of the story we are witness to, but also to the broader memory and cultural toolkit of the player themselves.

“Snowman” – Musical Narrative

narrative, n. – a spoken or written account of connected events

Musical Equivalent – Composition

Language, musical or otherwise, is all much of a muchness without application. Having now gotten an idea of EarthBound’s musical language, let’s take a moment to make a consideration of how they coalesce; and what more popular subject for case study could there be than “Snowman”?

One of EarthBound’s great tantalizing mysteries is this piece of music that welcomes us as we visit Jeff in his Winters boardings for the first time. It comes to us in defiance of unlikelihood, much like Jeff himself does: here, among all the thrillingly brief, artfully truncated pieces that appear across the work, lies a piece of genuine formal development, fitted with proper accompaniment, and an interesting structure, replete with a self-consciously dramatic modulation to the tonic minor.

As we are seeking here to view the dialogic interactions between various musical/narrative elements, to isolate the conflicts latent within them, and analyze how their values are derived thereby, let’s look at how some of the elements we’ve thus far considered interact within the body of this humble “Snowman.”

Musical Character – Melody/Harmony

“Snowman” has the touch of accented-dissonance-in-tight-spots we’ve seen Suzuki and Tanaka exhibit plentifully here, there, and elsewhere—note the way in which that opening B note strikes dissonantly against the #11 of the harmony, then resolves back to the tonic. The V/I approach to harmony adds gentler hues of color to offset those accented dissonances; but these are not the pastel colors of childhood: rather, they are the real, yearning colors of loss. Its pursuit of joy, not its possession of it, is represented in the way its harmony strives through the Lydian mode, not sufficiently carefree to bask in joyful majorness, or in gleefully dissonant, mix-and-match harmonic silliness as do “Onett” and “Apple Kid” respectively. This is an adult piece, one that heralds the arrival appropriately of a child forced to mature before his time.

Then comes the B-section; a shift to the tonic minor that is sophisticated in affect, a rephrasing of the original melody so distinct that it could barely even be called related, an arpeggiated Eb major 7 that has a wonderfully tidal rise-and-fall, and then a resolution that fairly leaves you hanging, with no cadence or even a real suggestion of one; what we thought would prove the piece’s resolution was in fact just a long crescendo leading to nowhere. Out of all the energy and unexpected turns stoking our listener’s tension, building seemingly to a head, we are left without catharsis, without anywhere to go. We can only recirculate to the beginning and experience that same vital-but-desolate A section once again.

Musical Setting – Ambience

Not much stays still in “Snowman,” and yet the piece’s ambience is difficult to mistake. The dryness of the flute voicing the main melody sounds as though it were primed by frigid tundra air, just as the natural reverberations of those sleigh bells in the background seem muffled by the close attentions of the woods of Winters. The presence of such blank space is as well-utilized an aspect of the design in this music as it was in the level designs of the Dry Dry Desert and Deep Darkness, isolating the richer musical elements in a spare and bleak surrounding.

An even more remarkable facet of “Snowman”’s ambience are those timid, even supplicatory synthesizer parts that respond to the principle phrases of the A section, dusting the wake of each one with arpeggiated passing chords, going through more or less every chord sensibly available to the melody at that point. The way they symmetrically unspool, the way their timbres of voicing are without almost any weight whatsoever, the way their annular motion makes the piece feel like it is rotating in place like a snowglobe, surely makes us feel that, as we listen, snow is tunefully falling at our feet.

Musical Allusion – Sampling

Though we do not enjoy any instances of direct sampling or melodic interpolation during “Snowman”—its sororal relation, “Winters White,” features a dewy-eyed interpolation of “Deck the Halls with Bells of Holly” at the tail end of its melodic arc—the piece is still fit to burst with those allusive elements.

The piece unfolds to the jingling of sleigh bells. They play an obvious role, their oddly stilted and unaccented rhythm laying an unmistakable feeling of wintry lethargy, and yet there is a deeper suggestion to them as well. To childhood, snow and winter are little more than the grotto in which Santa Claus dwells, the first snowfall the beginning of a protracted and seemingly never-ending countdown to Christmas Day.

For many of us, that countdown may be our first real experience of prolonged yearning and the melancholy of separation. If we consider “Snowman” as Jeff’s calling card, we may infer that melancholy of separation as deriving from a rather more personal source. Yet again, by allusion we have been led to a pair of deeper associations within this work of gaming: one association is directly our own (Christmas and sleigh bells in a Northern-hemispherical winter), while the other belongs pointedly to one of its characters.

Its bittersweetness must come from the bittersweetness of a longing that never ends, of a Snowman never given environmental cause to melt.

What’s in a Song?

“Snowman” is perhaps the fullest and most self-consciously compositional minute of music in EarthBound. And it comes from absolutely nowhere.

There is something to suggest the frustrated artistry of Suzuki and Tanaka in the piece: a feeling that, for all their liberation from the five basic waveforms afforded by the soundchip of the original NES, their being availed to a comparative menagerie of tones and synthesized timbres, their wish to fully actualize the fulsome spectrum of EarthBound’s personality in music is held back by the SNES’ limits on time. Had they the space to flesh out their arrangements and fit them to scale, we might’ve been allowed a particularly juicy section on musical structure and scale in this article.

And yet, in this game about children, those for whom time seems always to dilate even as it hurries on it way as usual, this enforced brevity seems thematically apropos.

But nevermind the thematic value of its brevity; “Snowman” tells us, with a candor that Jeff (understandably, and truly to his character) does not match, exactly what of Jeff we need to know before he embarks, before he has that heartbreakingly un-dramatic reunion with his father. It tells us of a melancholy that permeates a spirit too young to rightfully host it. It suggests to us a realm of unfettered, Nöelistic naivete that is just out of reach to the character for which the music speaks. It suggests the momentum of his thoughts, and, in its non-cadencing, the open-ended apprehension of his future.

In short, the music teases out the conflicts of Jeff’s pure existence, not merely decorating them with its own well-incorporated instances of harmonic and rhythmic dissonance, but actively embodying them, allowing us in not merely to Jeff’s expressible thoughts but also into the body of his experience.

To hear the #11s and V/I chords is not merely to hear music as it would appear in an unspoiled nature of perfect order. It is to be allowed into the mind of a character that, much like a real individual, must generally contend with both the joy and the sadness of their story at once. EarthBound, among all gaming narratives, is one of the most unvarnished and without vanity when it comes to confronting this emotional aspect of reality; it is this that gives the game the haunting energy that has made it famous.

“Snowman,” through its tightly packed facets, tells us more about Jeff than we might otherwise get to know, and stands to epitomize the narrative value of artfully composed music made to accompany a video-game narrative.

[1] Little Richard, “Tutti Frutti.”

Continue Reading

- A Comprehensive Theory of EarthBound series navigation: < “How EarthBound Brought Fatherhood to Gaming” | “‘If You Change Your Mind’: Shapeshifters of EarthBound” >