The following is part of Now Loading, a series that renders verdicts on whether or not your favorite video games deserve a place in the canon of works that have contributed to video-game storytelling in landmark ways. Read the series’ full mission statement here.

Can anyone clue me in as to why there are so few video games based in Greek tragedy?

I find it interesting that in the wide world of video-game storytelling, so few games immediately pop into my mind that use the tried-and-true structure of Greek tragedies to really tell a compelling story, in which the player feels as if it was she who was experiencing the consequences of her actions due to her own crippling hamartia.

Oedipius at Colonus, by Jean-Antoine-Théodore Giroust (1788), Dallas Museum of Art.

Greek tragedies are so simply constructed that it’s hard to come away from reading or watching one without feeling as if you were just as affected as the protagonist, so why aren’t there a slew of video games out there that use the interactive medium to its full extent and make people despair?

Take Antigone, for example, which is an excellent example of Greek tragedy in which the way right and wrong are arbitrated is based solely on the actions the characters take. To sum up the play, it is essentially one long drawn-out conversation between the titular Antigone and her uncle and acting king, Creon. A massive war had been waging for quite some time, and over the course of the battle, Antigone’s brothers Eteocles and Polynices both died.

Bummer on its own, but only further pushed into Bummerville when we realize that the two brothers were fighting on opposing sides, and Creon’s side won. Creon, then, declares that Eteocles be buried with the highest honors while Polyneices be left to rot in the battlefield. This is a big deal not only because it’s just a rude thing to do to your nephews, but also because it’s explained that, without a proper burial, Polyneices will not be allowed to enter the afterlife, and he will be forever shamed for his actions in death.

You know what actually happens in the play? Not much. There’s a lot of talking—specifically about the ethics of burials, what role an acting king should play when responding to an uprising, and just how awful Creon really is at ruling. The play is so brilliant that over, the course of their conversation, the audience shifts allegiance between Antigone and Creon based on the arguments that they are making, but ultimately we side with Antigone because she buries her brother and kills herself in protest.

Those two actions against her uncle and his twisted regime hold more weight than anything Creon can possibly say, and that is the true tragedy of Antigone: actions speak louder than words.

“Aaaaay, come on, Tiggy, leave the dead guy alone, eh?”

You see that action always trumps intent in proper Greek tragedy, and the moral at the end of the play is that we are only what we do, not what we think or say. After all, we know Oedipus grieves and feels immense guilt after realizing he slept with his own mother and killed his father, but he still did those things. Sorry, Oed: you’ve made your incestuous bed, and now you have to be blind in it.

This idea that we are only our actions—and that we are always responsible for those actions—seems like the perfect template for a beautifully-constructed video-game story. BioShock kind of touches on it towards the end, but then we, as the player, are given the means to circumvent the chiding and do what we want to do anyway. The actions we take that condemn us in BioShock are also the ones that ultimately grant us a “happy” ending, so there’s no real dice there.

I guess the kind of game I’m looking for is one that paints the avatar as a larger-than-life person with easily definable traits and weakness, with ambitions that can just as easily destroy their life as make things better for them. A game that follows the story of the downfall of this character, than puts that same character through a ringer of tough actions that have irreversible consequences. A game that, while seemingly ending on a high note, turns absolutely maddening when contrasted with the rest of the game and the flaws your character routinely shows.

I guess the kind of game I’m looking for is specifically God of War 2005.

God of War 2005 (to which I will henceforth be referring as simply God of War) was developed by Sony Computer Entertainment Santa Monica, with David Jaffe at the directorial and creative helm. Jaffe was the man behind the Twisted Metal series and also was unceremoniously placed as the creative figurehead/god-among-men in a particularly hilarious season of Sony’s The Tester.

This Jaffe’s a smart cookie, it turns out, and he set out to make God of War to be as visceral as possible, making the player feel as if she were a barbarian after hearing a bit of particularly upsetting news regarding her yurt. He claimed—quite rightly, as the game’s release would attest—that the game was a mixture of Devil May Cry’s fast-paced, high-action battles and Ico’s puzzle-solving. Whether it lived up to the latter is a point of contention amongst me, myself, and I, but when it comes to emulating the Devil May Cry style of combat, the game delivered time and time again.

God of War was so bloody brilliant (and brilliantly bloody, as it happens) that the game was released to immediate accolades and instant critical and commercial success. There was also a lot of fun stuff associated with the game—like how there was a hotline you could call to have Kratos, the main character, yell at you for calling him while he’s gutting somebody.

Games used to be fun and weird, folks.

But the really tragic part of God of War’s release was that people were so wrapped up in the über-violent ultra-buff male fantasy and interesting ancient Greek setting that certain very important aspects of the story went criminally overlooked. Critics and reviewers of the time would say that God of War was a fast-paced, visually stunning gore-fest with a serviceable story about revenge—and that’s about where they left it. As far as I can tell, not one person talked about how gut-rippingly, brilliantly tragic God of War is, and I consider that an apocalyptic sin.

I suppose it’s to be expected that a game known for intense gore and ultra-violence would be overlooked with that all-seeing, all-knowing critical and analytical lens. So, strap up your blades, paint your face the color of ash, and let’s dive into what makes God of War one-of-a-kind.

Story and Characters: I AM JUST SO ANGRY ALWAYS

God of War is the tragic story of perturbed steroid given life: Kratos, a man who is solely defined by his unbridled rage and solely driven to somehow forget the terrible things he has done.

Like the true arrogant man I am, I referenced the Greek term “hamartia” earlier in passing, so allow me to rescind some arrogance, cry mea culpa, and explain what that means in the context of a Greek tragedy.

Hamartia is literally translated as “to miss the mark,” or “to err,” but is used when discussing Greek tragedy to refer to the “tragic flaw” or fatal character flaw by which the main character in a tragedy is defined. This tragic flaw is the driving force behind every decision a character makes, and the actions that ultimately lead him or her to his or her downfall.

In Kratos’ case, you don’t need to peer deeply into his blackened soul to understand that his tragic flaw is his burning rage which is the fire fueling his quest for revenge.

*Burning rage intensifies*

Before jumping into the plot, it’s prudent not to rush past Kratos as a character. Yes, the only knob on his personality switchboard is “anger,” and it’s cranked up to at least eleven even when he sleeps. But, while that is the most important thing to understand when analyzing his character and the story that unfolds around him, it’s just as important to look at his character design—that is, how he actually looks.

I’ve mentioned in past articles that a character having a memorable design can do wonders for a game, especially if it’s a mascot-based game like Crash Bandicoot. However, beyond marketability, character design can be an incredibly useful tool when it comes to getting the player to identify with the avatar.

Kratos is a big, hulking white and red monster of a Greek man, and so you’d think that it would take some doing before the player starts feeling like she is Kratos when playing the game. When it comes to priming then player to feel as if she were the avatar, having an overly-silly character design can be a deterrent. Take a look at something like Final Fantasy 0-Type, in which the characters which you are able to control look as if a Halloween store threw up all its unsold costumes onto an already cliched-looking anime character. It’s silly, and what’s more, it’s off-putting if someone is trying to identify with the character throughout the story.

What does this guy’s morning routine look like? So many detachable parts…

That line of reasoning may seem to point to Kratos not being identifiable, but I actually consider him to be the exception that proves the rule, here. Yes, he’s a hulking maniac with red body tattoos, but he’s still clearly a man. He’s pretty particular in his word choice, so you don’t feel like he’s thinking or saying too much in your stead, and while he’s a buff dude, he is by no means an impossible-looking human.

We see what he looked like in his pre-ashen-skin flashbacks, and he looks like someone we might see playing a tragic character on stage. He’s over-the-top and he has swords chain-grafted to his arms, but he’s not so other that the player doesn’t develop a connection with him as an avatar.

So there we have it: an angry murder machine with whom you are primed to identify from the outset. Let’s keep this train a-moving.

Our story begins with Kratos standing on the edge of the highest mountain in Greece; as he plunges himself into the Aegean sea below, the narrator lets us know that things would not be going the way Kratos had envisioned.

So we then skip back three weeks, which seems a rather reasonable amount of time in which an epic story took place, to see Kratos on his ship ripping the various heads off the mythical hydra at the behest of the god Poseidon. He finishes the monster off, beds some busty ladies, and the narrator comes back to let us know that, no matter the earthly pleasures in which Kratos partakes, he is still a cursed man who takes no joy in life.

Enraged, Kratos summons Athena for a little chat.

Athena, Goddess of Screwing People Over.

Kratos claims that he has been doing the gods’ bidding for the past ten years, and that it was about time they made good on the promise they had made to him all that time ago. You see, ten years prior to the start of the game, Kratos was an up-and-coming warrior in the Spartan army. He was as vicious as he was angry, and on one occasion when he was about to be killed by an opposing army’s warrior, he called out to Ares, the God of War, to smite his enemies in return for unending service to him.

Seeing an opportunity to manipulate a pretty strong guy, Ares agreed and wiped out the entire opposing army. In a contract signing of sorts, Ares bound the Blades of Chaos to Kratos’ arms, burning them into his flesh so that this man, driven by anger and bloodshed, would never be without his killing tools.

In the coming months, Kratos was at the beck and call of Ares who would send him to embark on battle after battle, fueling the machines of war with every barbarian slain at his feet. One such outing was to a town worshipping Athena, and, in the first of many instances of his hamartia coming up to bite him, Kratos unknowingly slaughtered his wife and child in his war-driven rage.

We then learn that not only had Ares sent Kratos to decimate this town, but that he had actually transported Kratos’ wife and child to the town so that he would slaughter them in his rage. Evidently thinking this would somehow release Kratos of his earthly ties and transform him into the perfect killing machine, Ares realized he had made a drastic miscalculation: Kratos instead renounced his piety to Ares and vowed revenge for his wife and child. The oracle of Athena’s temple bound the burnt flesh of Kratos’ victims to his skin, covering him in an ash that would never wash off, and earning him the title “Ghost of Sparta.”

I am not by any means a scholar of Greek literature, but I know enough to recognize the first instance of a man’s hamartia dooming him for the rest of the story. Blinded so thoroughly by rage and bloodlust, Kratos committed an act so heinous that only the worst of the worst tragic figures (looking at you, Heracles) woud perpetrate it. His actions, driven by his tragic flaw, sealed his fate as a man controlled by that flaw.

So, naturally, Kratos vows to move heaven and earth to make the non-stop memories of his terrible actions disappear from his mind. How will he do this? Well, he assumed being the gods’ personal errand boy might net him a favor after ten years.

No dice, I’m afraid.

“What can I say, Krates, you should have tried to be less of a horrid monster.”

Athena informs Kratos that Ares is waging war on her city, Athens, and that the only way to rid himself of his horrid memories is to kill the god of war himself. Kratos happily agrees to do this, out of a deep-seated sense of revenge. When he asks how a mortal can fell a god, Athena tells him that the only power to kill a god rests in Pandora’s box, which is currently chained to the back of the fallen Titan, Cronos. Kratos obliges and sets out for the Desert of Lost Souls to collect his ultimate weapon.

So here we have the entire tragedy set out before us: a man driven by rage and revenge is tasked with killing a god so that he can be rewarded with a clean slate, forgetting all the terrible things he’s ever done. And let us remember that Kratos is always the bad guy in this situation. Yes, Ares set in motion the brutal death of his wife and daughter, but without Kratos calling out to Ares in the first place because of his undying thirst for bloodshed, nothing of the sort would have ever happened.

That initial pact with Ares, in which Kratos agrees to continue indulging his hamartia, is what leads to the greatest tragic moment a character can endure: losing his family by his own hand. And yet, even with Athena sending him out on this mission, even with Ares putting his family in place to be killed, never forget that Kratos made his bed by engaging in ultra-violence.

With that said, the game tasks you with engaging in ultra-violence on your warpath to brutally murder a god. Are we seeing the brilliance here, yet? Let’s continue the wrap-up before we sink our teeth too deeply into the genius at play in this wonderful interactive story.

So, via a path of gore and blood, Kratos grabs Pandora’s Box, only to have it plucked away from him by Ares. Knowing just what exactly Kratos is planning with his godbox, Ares kills Kratos, sending him to the Underworld.

But, as we all know, unless you’re a disgraced warrior whom some despot refuses to bury, death doesn’t mean all that much in Greek myth. Kratos awakens in the land of the dead, determined now more than ever to rip the still-beating heart from Ares’ chest. More blood, more gore, more of the same ultra-violence as Kratos fights his way through the legions of the Underworld to escape back to the land of the living.

EVERYONE IS SO MAD IN THIS GAME ALL THE TIME

After emerging from the Underworld, Kratos locates Pandora’s Box and manages to open it before Ares can stop him, and he grows in size and power to rival that of a god. Ares, in a vain attempt to stop Kratos, rips the blades off his arms, and drains him of any magical energy that he may have picked up along his tour of ancient Greece.

Now that Kratos is disarmed, Ares attempts to play on his horrible memories, torturing him with the things he’s done and the lives he’s taken. And yet, it should shock no one that the Ghost of Sparta doesn’t need any fancy chain-blades or magic spells to utterly destroy the god he’s come to hate so much. Wielding a mythic weapon known as the Blade of the Gods, he kills Ares in one final act of revenge.

So, with the God of War slain by the Ghost of Sparta, we wait for that other Greek tragedy staple: our moment of catharsis. That precious moment in which the hero has accomplished what he set out to accomplish, and everything is right with the world. And we wait. And we wait. And we wait…

And Athena shows up, telling Kratos that while the gods have washed him of his sin, he will never truly forget the terrible things he did. No being, mortal or immortal, can erase the horrors from Kratos’ past. With his mission finished and no family to live for, we are back to the opening scene of the game: Kratos tossing himself off a cliff.

Yes, the area’s really called the “Suicide Bluffs.”

Kratos’ suicide after realizing he can never erase his past actions would be tragic enough, going by your run-of-the-mill Greek metric. I mean, after all, every single thing he’s done over the course of the game has been in the name of his rage and anger, the selfsame flaw that led him to suicide. Again, the gods had a strong hand in leading Kratos throughout his long and painful journey, but at no point did they force him to do anything he wasn’t already capable of doing.

He bartered with Ares. He killed his family. He chose to work for the gods, and he blindly followed Athena’s orders just like he had blindly followed Ares’ before her. Nothing learned, nothing changed—just more heartache ending with suicide as the final nail in the coffin. Tragic, right?

Wrong. Sad? Yes. Tragic? We have not yet begun to break.

Just as Kratos is about to plunge into the Aegean sea, Athena pulls him from his fall and tells him that, because of his work against Ares, the gods have seen fit to make him the new God of War—forever overseeing the same anger, rage, and bloodlust that brought him to the very precipice of Olympus.

As the game ends with Kratos atop his throne of gore, we realize that, far from a reward, Athena and the rest of the Greek gods have just sentenced Kratos to the worst punishment he could ever be forced to endure for all time. Not only will he never be able to forget all the horrors he has wrought, but he will also be forced to interact with men and women just like him: just as angry, enraged, and battlecrazed. His choices have led him down a terrible path, and the end of the road is a constant, aching reminder of the very thing he has been trying so hard to forget, and the very hamartia that led him here is now his godly title. He has become, in every way imaginable, the God of War.

That, my friends, is Greek tragedy.

Look on Him, Ye Mighty.

Gameplay, Music, and Visuals: A True Epic

A Greek tragedy of this magnitude deserves to be boisterous and over-the-top in every way possible, and when it comes to screaming bombast, God of War delivers in spades. To begin with, this game was late enough in the PS2’s life cycle that the visuals still hold up pretty well to this day. Despite being from 2005, nothing about the game seems shoddy or unpolished, and for a story being told on such a grand scope, it truly knocks it out of the park with visuals.

From the size of Cronos and his lumbering gait, to the frankly frightening harpies, all the way down to Kratos simply swinging his blades around, each and every frame of God of War reflects the deliberate thought put into it. The game is also one of the few good examples of an off-maligned type of gameplay: namely, quick-time-event (‘QTE’) button prompts.

Games often use these to cut corners so that the game looks more cinematic than it actually is. And while they are an integral part of God of War’s gameplay, they never feel overbearing, boring, or unfair in the way that most QTE button prompts tend to be. They’re used primarily to end combos, which results in a nice little death animation that still makes the player feel as if they were the one performing the action.

Titans have every reason to be grumpy, in my opinion.

When Jaffe claimed that the gameplay would have the combat style of Devil May Cry, he wasn’t exaggerating. The game feels very familiar to anyone who has played that series, and is an easy thing to pick up for those players who haven’t. Overall, the control you have in different combat scenarios makes you identify even more with Kratos, because the actions you are executing are so visceral, and combos landing on ancient Greek monsters feel like they actually have weight behind them.

Everything in the game—from abilities you pick up, to the puzzles you solve as you progress, to just hacking and slashing your way through Ancient Greece—makes you feel as if you were Kratos. For better or worse.

There’s not much more to say about the visuals that I haven’t already touched on when discussing gameplay, but it’s important to note that every single boss fight manages to feel intimate and gigantic at the same time. From the very first boss, the Hydra, you are able to get a sense of what the scales of fights are going to look like as you progress through the story. By simply putting him in contrast with the other deities and monsters you fight throughout the game, you get yet another palpable idea regarding just how strong and larger-than-life your avatar is.

Rage is a powerful tool. You can always count on it to destroy monsters in one way or another.

Who put this picture of Kratos here right after I said that rage always destroys monsters in one way or another? Who did that? What? It was me? During editing? Got it.

Let me end by gushing about the music in this game. The score is as epic and sweeping as the story, complete with a haunting chorus (another staple of Greek tragedy, by the by) that follows Kratos on his journey. Nothing in this game feels small or quiet, and the constant scream-singing of the chorus as you slice your way through monster and man alike is something to behold.

What’s more, the sound design does everything in its power to make you really experience every bone crunch, every blood spurt, and every death rattle as one of Kratos’ blades rend some poor sod’s flesh. The sounds and songs of God of War do just as much to make the player identify with the protagonist as anything else. The sights, the sounds, and the very feeling of tearing your way through enemies are all fine-tuned to make sure you are experiencing the viscera in real time.

Impact on Video Gaming and Culture: Rage Sells, Kid

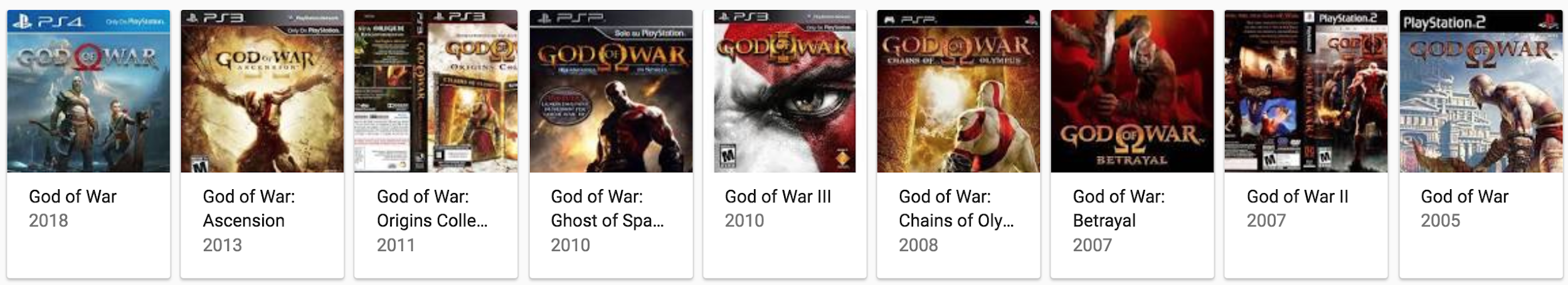

God of War certainly set the bar a little higher not only for games like it, but for all games in general. The combined power of a new, instantly recognizable mascot for Sony and a brilliantly constructed game behind him spelled nothing but success for what would inevitably be a franchise.

And franchise they did.

Here we come to one of my many gripes with the way in which good storytelling is often at odds with good business sense. Let me show you why.

Let’s put on our hypothetical hats and say that you, Dear Reader, are David Jaffe, and I am some big-wigged Sony executive coming to congratulate you on the insane success of your latest little game thing, God of War. Naturally, you’re excited that this story that you’ve put a lot of effort and time into is getting you praise from the public and your bosses, so you greet me warmly and shake me firmly by the hand.

You notice, however, that your hand (a hand that has crafted a brilliant masterpiece) is leagues warmer than my hand, almost as if my palm is some sort of heat void. You further notice that I have a long, rather intense looking dagger concealed in my coat sleeve. Feeling the joy escape the room, you try to sidle towards the door, but my grip is too strong, and I only let you leave when you agree to do a sequel to the game that is making me so much money.

“But I ended it so perfectly,” you say, handsome lip trembling.

“Yes,” I whisper with ten-thousand damned voices, “And now you will start anew.”

Like the Oracle at Delphi, you see brief glimpses into your future with sequel after sequel followed by prequel after prequel, the mystique and majesty slowly falling off your beloved story like the the bloom off infinite roses, and, although you see a glimmer of hope in the far-off future coming from your pal Cory Barlog, the years ahead are arduous and frightening, with many, many dollars lining the pathway.

Conflicted, your hand falls from mine, and what was a dagger just moments ago becomes a thin fountain pen, which I place in your hand.

“Anyway, yeah, so good job, babe, I’m just gonna sign you on for another and then we can discuss your role in future installments, ’kay? Thanks, kid, great job, Giddy Warrior’s really doin’ well!”

And so, like Kratos on his throne, you crawl back to your office chair and wonder in horror at the years to come. But hey, man, you made a great first game.

At least, that’s what I heard happened.

Protracted sigh.

BONUS LEVEL: You Monster

Remember all that stuff I mentioned in the introduction about why there’s not a perfect game about Greek tragedy? About how the fact that Greek tragedy is defined by our flawed actions setting us on the path to their own destruction? Well, God of War is the perfect example of someone taking all the tropes of Greek tragedy and melding them perfectly into an interactive experience that truly makes the player feel as though she has undergone a tragedy herself.

Not only are you primed from the very start to identify with Kratos, but time and time again you reaffirm your identification with this tragically flawed man by continuing to hack and slash your way through man, beast, and god alike. Every single tragic event that befalls the protagonist of a Greek story is the consequence of their own decisions, and they are then defined by those decisions at the end of the story regardless of how they felt or thought while taking those actions. Just as Kratos dives deep into the well of his hamartia with each swing of his blades, so too does the player indulge in their rage and bloodlust by moving the story forward.

In just the same way as we identify with Link from Ocarina of Time in a way that makes us feel like a hero, so too are we meant to feel like the victim of true Greek tragedy by indulging in God of War.

The epic sights, the giant boss fights, the visceral sounds, and the very feeling of tearing people limb from limb make us indulge in not only Kratos’ flaw, but ours as well. And what do we have to show for it at the end? Not catharsis, but a scenario in which the good outcome was suicide, and the catastrophically bad outcome was that we fell victim to the tragedy set out for us, leaving the game secure in the knowledge that, just like Kratos, it was our own actions that made this happen.

And maybe the thoughts you had while playing the game regarding how cool it was to utterly destroy people is just what Kratos might have felt—even when he tore through the flesh of his own family.

Just a thought.

VERDICT: Godlike

I think it’s fairly apparent at this point that God of War joins its brethren in the pantheon of the Video Game Canon. Sure, a few elements that were products of the time might decrease your overall enjoyment of the game by a bit, and the sequels leave a bit to be desired in my opinion, but that’s for another day, anyway.

As it stands, God of War is the perfect example of a brilliant team of developers coming together to adapt the very idea of a Greek tragedy, and, in the process, they not only told an impactful, excellent story on its own, but they were also able to make the player experience the very tragedy that befell the protagonist.

Welcome, God of War. Your throne is waiting.