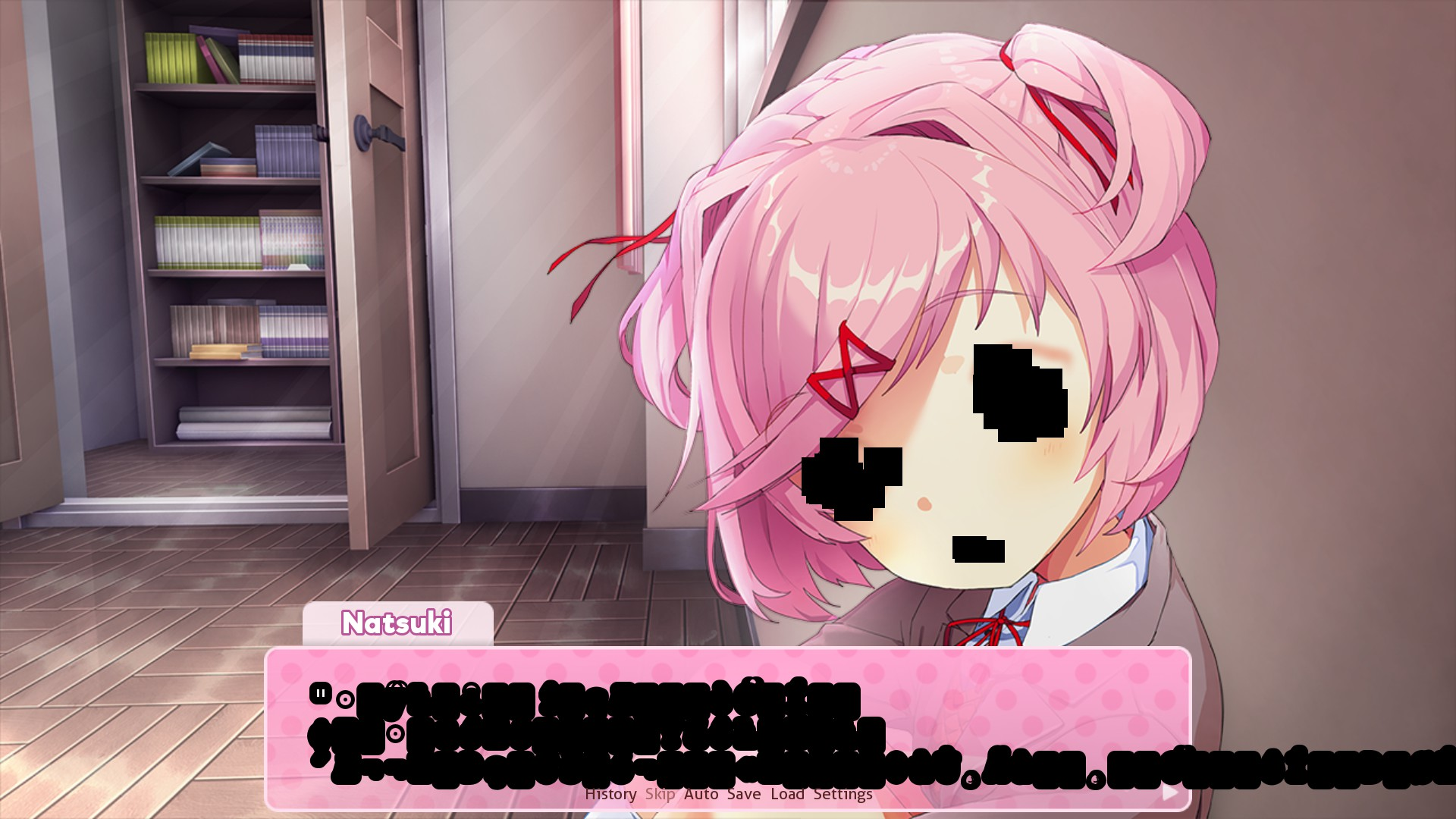

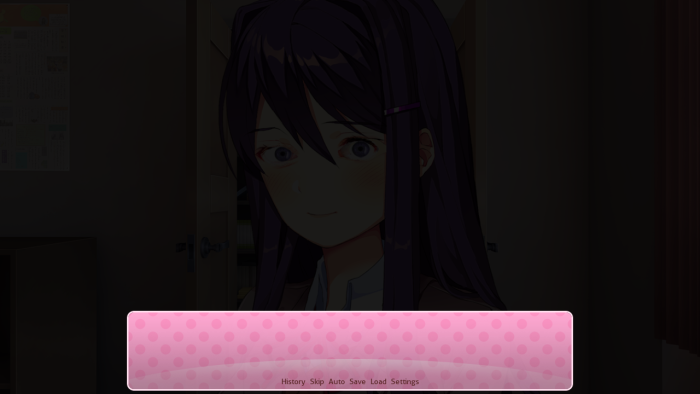

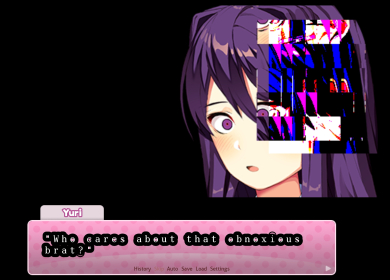

Take a moment to stare into Natsuki’s dark, glitched eyes.

What do you feel?

Maybe this picture sends shivers down your spine, or maybe it gives rise to a deep sense of unease. Either way, this is quite a horrifying visual from Team Salvato’s psychological horror masterpiece, Doki Doki Literature Club—a game that purports itself to be a lighthearted anime dating simulator, but that ends up leaving the majority of its players crying themselves to sleep at night, for fear of Monika taking over the world.

Doki Doki Literature Club has many of the ordinary elements of horror, but it is not your typical horror story. It is a profound, complex work of fiction that is only made possible by the special storytelling features of video games.

In this article, I argue that Doki Doki Literature Club (“DDLC”) creates a unique sense of psychological horror through four main mechanisms, all of which are peculiar to the gaming medium in some way. These mechanisms are:

- Subversion of player expectations

- Illusion of player choice

- Trapping the player within the game’s story

- Breaking the fourth wall between player and game

Join me as we consider each of these in turn in order to discover just how DDLC writes its way into our hearts—because it’s not in the way we’d first expect.

1. What you see is not what you get

The most obvious aspect of DDLC’s psychological horror is the way in which it subverts player expectations at almost every turn.

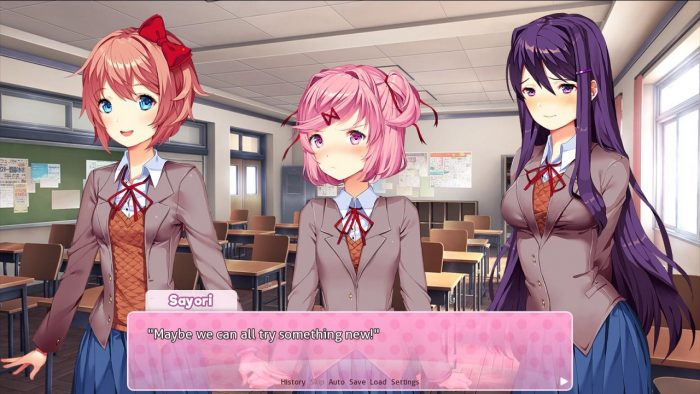

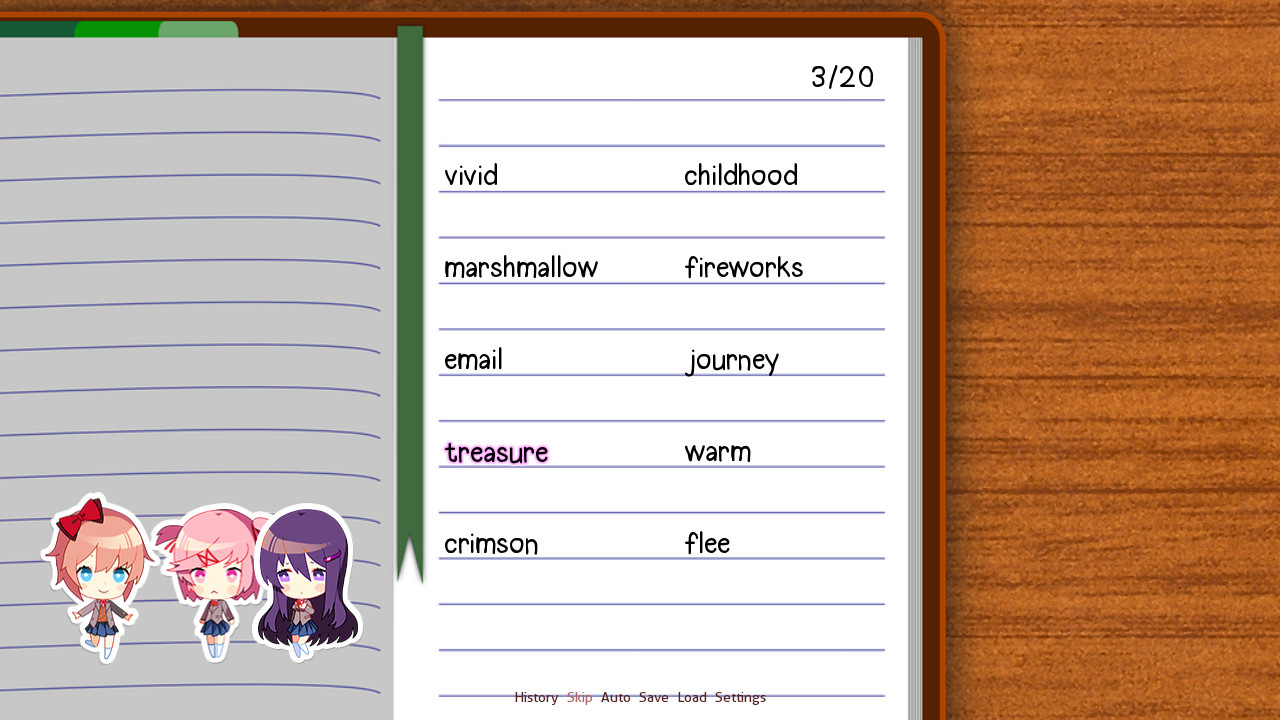

We start off with what looks like your typical anime dating simulator in Act 1, during which the player can romance Sayori, Natsuki, or Yuri, spending time with their love interest performing the standard dating-sim tropes like reading manga or eating chocolate together. The player also gets a chance to try their hand at DDLC’s poem-writing mini-game, in which they can pen a literary masterpiece to woo the girl of their dreams.

After becoming acquainted with the girls of the literature club, Sayori then confesses her feelings for the player, and they have the option to accept her confession or reject her. If they accept, a couple of unique lines of dialogue ensue, and the player receives a unique image of Sayori (shown below) as a sort of “reward.”

Again: so far, so typical for an anime dating simulator.

However, this is as close as DDLC ever gets to a typical dating simulator. No matter which choice the player makes regarding Sayori’s feelings towards the protagonist, she becomes increasingly melancholy and depressed throughout the first act, resulting in her untimely suicide by the end.

This is an incredible shock to the player: Sayori seems so carefree and innocent at first, only to perform a complete u-turn in terms of personality and demeanor, ultimately taking her own life. This dramatic turn of events is harrowing, to say the least. More to the point, though, it marks the beginning of the end for the player’s sanity.

Aside from the horrific content of this first act, what is so fundamentally shocking to the player about DDLC’s shift from dating simulator to psychological-horror visual novel is the fact that video games are not normally supposed to undergo this kind of dramatic change.

When you first start playing a game, you learn the rules and mechanics of the underlying game engine and then become accustomed to certain archetypes and tropes within the game world. If the game belongs to a pre-existing genre, then some of these rules and customs are inherited from previous works. In the case of DDLC, we have:

- the typical tsundere character, Natsuki, who is shy and often snarky at first, but then warms up to the player

- your standard, warm-hearted girl, Sayori

- Yuri, the much more elegant, refined love interest

Right from the get-go, everything about DDLC convinces the player that it does indeed conform to the dating-simulator genre, and that it will continue to do so in the future. After all, what would games be without their rules? The deterministic way in which players interact with a game is fundamental to a satisfying, enjoyable gaming experience.

For this reason, the way in which DDLC switches its core concepts so dramatically is a gross breach of trust between player and game. We, as players, almost feel betrayed by the architecture of the game itself, and this subversion of our expectations is enough to catalyze the onset of psychological unrest and fear.

It’s not just Yuri that’s terrifying!

No doubt, there are many horror games out there: but these games have their own rules, and veteran horror players know what rules to expect at the outset. DDLC violates its players by doing something much more eldritch: taking something thoroughly non-horrific (a dating simulator) and gradually unraveling the basic principles that make it inviting and comforting.

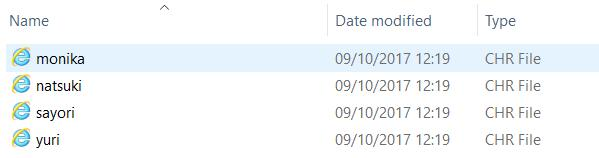

We witness this breaking of traditional game rules again in the third act, when the player is forced to delete Monika’s character file to escape her hour-long dialogue loop in the ruined classroom. Video-game stories are normally highly self-contained experiences: the player does not tamper with or even view the game’s files, rather experiences the interaction of the game code only at the very highest visual and interactive levels. By forcing us to actually deal with the game’s low-level features, our expectations are once again turned on their head, and we develop a sense of great unease as this very un-video-game-like behavior.

This would be akin to reading a novel and then, on one of the very last pages, being told to rip out the first 50 to uncover a secret ending. Such a turn of events would be highly shocking and probably quite disturbing for the unsuspecting reader, and this is precisely the response that DDLC elicits.

2. Did you really think you had a choice?

Yet DDLC goes even further beyond what a normal game would do by taking away the player’s choice—in the worst way possible.

Both Sayori’s suicide in Act 1 and Yuri’s tragic death at the end of Act 2 are unavoidable events: they occur no matter which poems the player writes, no matter which dialogue branches they choose to follow. Consider Sayori’s untimely demise: the first time the player sees what has happened, they will immediately think that they could have somehow prevented it. Since the game seemingly gives you a choice to either accept or reject Sayori’s confession of love, it would seem logical that the “other” choice—that tantalizing choice that you didn’t select during your first playthrough—would somehow help Sayori and save her from her awful fate.

Some players might go back and try the other option, only to realize the futility of their actions; others might continue, constantly burdened by the guilt of not saving Sayori. In either case, sadness and confusion arise. The illusion of choice lifts the player up and then brings them crashing down to the reality of DDLC: the player is not the one in control. This is a game, but not one that can merely be “played” like other conventional titles.

In Yuri’s case, the player is also given a choice to accept or reject her confession of love, and, just like Sayori, Yuri will die no matter which option they pick. But by this point, the game’s agenda is already clear, and so it doesn’t really come as a surprise when Yuri cannot be saved. This helplessness that the player feels feeds into the general atmosphere of despair in the game, creating a distinct kind of horror: the horror of losing control.

The very reason that DDLC is able to create such psychological pain is because it is a video game, and thus has an element of interactivity and choice. DDLC in book form just wouldn’t have the same impact because it couldn’t give the player the same kind of apparent freedom, only to snatch it away at the worst of moments.

3. Doki Doki Hostage Club

One of the interesting side effects of the player’s lost control is that they begin to feel trapped within the game’s story—a story that doesn’t seem to respect the ordinary boundary between game and reality.

When watching a horror movie, you might have to view some particularly harrowing scenes to get through the story, but at no point are you forced to watch these parts—you could just skip forward or close your eyes for the bits you find uncomfortable. But DDLC laughs in the face of traditional media. By virtue of being a game, you must play to progress. This sounds like a basic idea, but the fundamental idea of playing the game to progress is what makes some parts of DDLC so utterly horrifying.

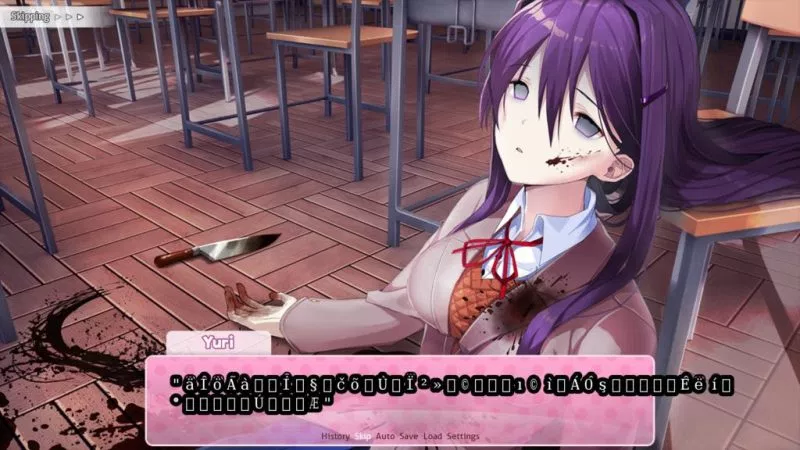

The most striking example of this is when Yuri stabs herself to death, after which the player is forced to sit and watch her body decay for an entire weekend, while her character spits out 1440 lines of meaningless dialogue. Even on the maximum fast-forward speed within the game, this process takes at least 5 minutes of real-world time—and, most likely, it will take longer as the player constantly waits to see what happens next.

There is no easy way to close one’s eyes at this scene or to just skip past it, as one could in a horror movie. The player is forced to sit there and click through every line of glitched characters, not knowing when it will come to an end. It is as if the game itself were aware of the player’s expectation of being able to willingly move past this scene: it seeks to spite the player by instead prolonging it to a sadistic extreme.

Notice, then, that DDLC isn’t just a horror game that disguises itself as a dating simulator: it’s a horror game that terrifies players by taking the ordinary conventions of a non-horror genre and makes those very same conventions horrifying. The still images of visual novels are typically serene and contemplative; here, that same convention of the still images forces the player to engage with a rotting corpse that becomes more horrifying the longer you look.

And you can’t look away.

4. There goes the fourth wall…

The final way in which DDLC effectively generates horror is by breaking the fourth wall with the player. Many famous games—such as Undertale—rely heavily on fourth-wall-breaking to dissolve the barrier between the real and virtual world, but DDLC’s use of this technique is almost beyond compare.

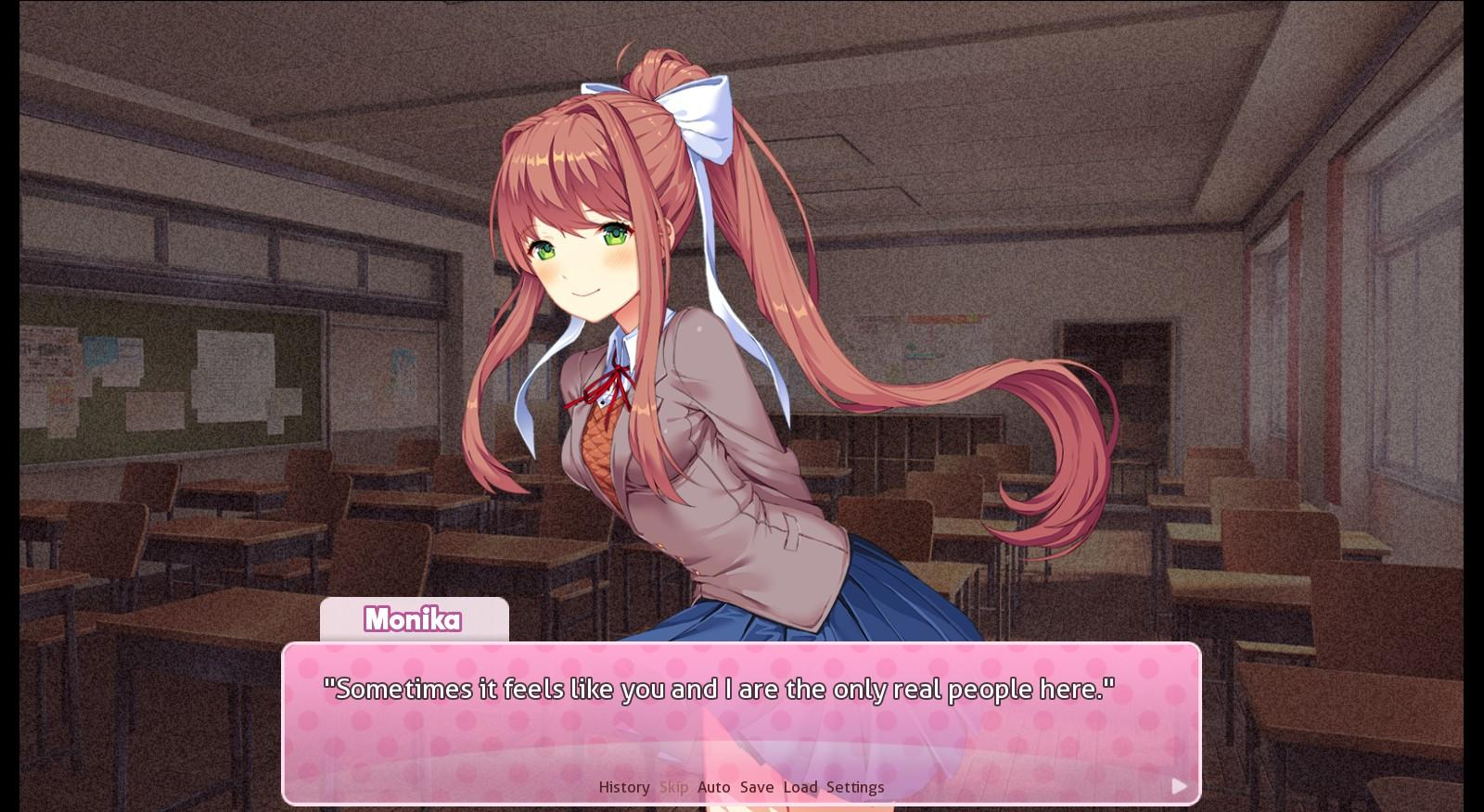

In the first two acts of the game, there are hints of fourth-wall-breaking in terms of the game itself toying with the player and their desires. However, the third act is really when this aspect comes to the fore in the form of our beloved Monika.

After proceeding to take full control of the game and delete all of the other characters’ files, Monika sits down with the protagonist in a distorted version of the late literature club’s classroom, which is now floating in space (perhaps suggesting that this part of the game is literally taking place outside of the game world!). She explains that everything that happened up to this point was her doing, and that she is aware of being trapped inside the game as a fictional character. Furthermore, she was the one who accelerated Sayori’s decline into depression and Yuri’s obsessive tendencies.

And all of this, she did for the sole goal of spending more time with the player.

At this point, it is clear that it is actually not the game that is playing with the player: Monika herself, a sentient character within the game, is the one pulling the strings. Not only does Monika appear to be sentient—almost like a player in her own game world—but she also confesses to being directly in love with us, the real flesh-and-blood human beings in the real world.

No longer are we living through our fictional protagonist. Rather, we are in direct conversation with Monika, a seemingly conscious being, and all barriers between the game and reality are broken down.

This moment of direct, intimate conversation with the player removes the comfort barrier that normally exists when playing a game—or when consuming any other media form, for that matter. Indeed, if the player does try to save and reload the game and escape from this fictional setting, a message—presumably from Monika, who is control of the game—pops up, saying that “there’s no need to save the game anymore, don’t worry, I’m not going anywhere.”

Even in reality, where the player is supposed to have absolute control over the game, they are beholden to Monika’s whims. One might even go as far as to say that the player has become like a video-game character, subject to the whims of a real player, who, in this case, takes the form of Monika. In essence, the roles of player and NPC have been reversed. In this way, DDLC doesn’t simply break down the fourth wall: it quite precisely picks it up and sets it back down in the reverse direction, with the player inside of the game’s economy and Monica as the external agent acting upon it.

Part of the pleasure of enjoying horror movies, books, and games involves being dissociated from the situation at hand.

- The monsters only exist behind a TV screen.

- Not scary ghost will jump out of the pages of a book and haunt you.

- The game’s monster won’t hunt you, no matter how doggedly it hunts your avatar.

The viewer can take solace in the fact that they exist in the real world, safe from the horrors of their current entertainment, and this gap between real and fictional leads to security and enjoyment.

DDLC takes away this most fundamental security from the player by drawing them into the game world and placing them in a position of powerlessness. It is a game filled with horror, but it’s also a game that refuses to let you sit back and enjoy the horror—even for a single moment. This idea of direct, transparent communication with the player is something that comes up in other psychological horror games, such as the Zero Escape series, which I have written on previously.

This profound perversion of the boundary between real and fictional persists through Act 4. If the player restores Monika’s character file after starting a new game, she will say, “please stop playing with my heart. I don’t want to come back”, and her character file will then be deleted. Monika is a like a real person: she is wounded by our rejection of her love, to the point that she literally prevents us from interacting with her further. This is what causes us to feel awful for rejecting her, and for being slaves to our self-centered desires to date one of the other characters aside from Monika.

Yet even this perspective is subverted, as the player does not actually have the option of dating Monika during the game. Looking at this from the angle of the player-as-NPC, this is like the virtual player (put in the role of an NPC) not having the choice to date Monika (the “real” player), and then being criticized for rejecting her, even though we couldn’t get to know her at all. In this situation, although we feel bad for Monika, she also seems incredibly superficial and callous because she is expecting us to love her despite not being able to interact with her during the game.

And that sense of being deeply misused, with no safety or power to make things otherwise, is exactly what DDLC wants to make us, the true players, feel like.

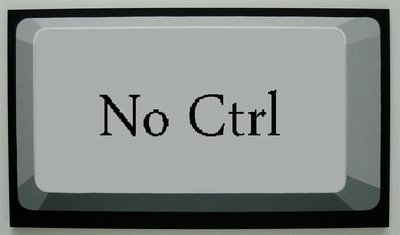

A summary of the game’s attitude towards its players.

What Doki Doki writes into our hearts

All of the heartbreaking and mind-bending of DDLC are not for nothing. The game has a message to convey to its players, one that perhaps could only be effectively communicated through its interactive structure.

Ultimately, this game is a comment on the dating-simulator genre as a whole, and on the players who indulge in superficial, callous behavior by partaking in such experiences. Just as the player’s freedom of choice is stripped away from them, fictional characters in these games have no freedom of their own. DDLC forces us to consider the plight of such virtual humans in parallel with our own, harrowing experiences at the hands of Monika.

By leading us to believe that the game is a standard dating-simulator experience and then providing us exactly the opposite, Doki Doki illuminates our shallow and greedy expectations for what this type of game is.

Perhaps the real horror of the game, the one that we don’t want to admit to ourselves, is how it acts as a mirror onto our gaming practices and our self-concept as gamers. In essence, we are just like Monika when playing other games of this type: tyrannical, uncompromising, fictional overlords who will stop at nothing to get exactly what we want, even if it means the destruction of everything around them.

We start DDLC unaware of what we are, and then, through a lengthy process of slow realization, we finally come to understand that what is truly horrifying is not Monika, but rather us: the players, and our approach to games. Upon realizing this, we might decide to change our attitudes, we which be the most truly “meta” success of Doki Doki Literature Club: changing people’s lives in the real world through their experience with a video game.