The Hero of Time Project is an attempt to re-examine the narrative vacuum in the Legend of Zelda series between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, and to utilize the concept of fan fiction to logically fill in some of the gaps using information presented to us in existing lore.

The Hero of Time Project is an attempt to re-examine the narrative vacuum in the Legend of Zelda series between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess, and to utilize the concept of fan fiction to logically fill in some of the gaps using information presented to us in existing lore.

Ladies, gentlemen, and Sonic fans, welcome to the beginning of our series here on With a Terrible Fate: We are the Know-it-all Brothers, Jaron R. M. Johnson and CJ Thomas, and this is the Hero of Time Project. In our introductory article, we’re going to be taking a look at fan fiction. Specifically, we’re going to be showing fan fiction in a different light: one that shows how fan fiction can contribute to its source material, shows how fan fiction can be rigorous and analytical, and one that hopefully will lead us in the direction of being able to talk about fan fiction as more than just a thoughtless, mindless cacophony of shoddy, cobbled-together smut (not that there’s anything wrong with some good, old-fashioned smut).

Fan fiction is often viewed as a humorous and rarely-valuable form of masturbatory wish-fulfillment writing created for the sole purpose of exercising good grammatical writing practices and making characters with little-to-no romantic chemistry bone one another à la E. L. James’ 50 Shades of Grey, wherein a brooding vampire CEO makes visceral, poorly-written love to a brooding teenager secretary.

But what if we told you that fan fiction can be so much more than that?

In fact, what if we told you that, contrary to every experience you’ve ever had or heard of, fan fiction can (and already does, to an extent) exist to enrich the canon of the series in a way that is rigorous and analytical? That instead of having Sonic the Hedgehog, Crash Bandicoot, and your cool, edgy OC all comically blowing up the house of your school bully or kicking your step-dad in the nuts, you could see fan fiction fill in existing plot holes from previous stories in a contributory way that we, as players of games, watchers of movies and television, and readers of books, already do?

God’s gift to fankind.

Fan fiction that brings value to its source material is not without historical precedent, either. In the case of Star Trek, the first fanzine (fan-written magazine) for Star Trek, Spockanalia, was published during its second season in 1967, and contained many examples of fan fiction. This bolstered the fandom and interactions between fans and cast, which better allowed the show and its creators to understand what the fans wanted. This also set the precedent for modern-day fan fiction as we know it.

Cover of the first issue of Spockanalia, 1967.

In fact, the first issue of Spockanalia contained a letter from Leonard Nimoy himself, wishing good luck to the fans who were authoring it. Joan Marie Verba discusses this in her 1996 editorial, Boldly Writing. Nimoy’s letter represents one of the earliest examples of someone involved with the source material acknowledging and empowering fan fiction.

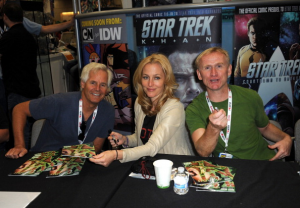

Several decades later, in the mid nineties, science fiction fans saw the release and subsequent mass adoration of one of the most critically acclaimed television shows in U.S. history, The X-Files. This television show brought about one of the earliest, if not the first, examples of a strong online presence of a collective of fans who were interacting with one another. The creator of the show, Chris Carter, saw this as a valuable tool, and leveraged the existence of this fanbase frequently throughout the show’s multi-decade run. Kumail Nanjiani has a podcast entitled The X-Files Files, in which he discusses the series episode-by-episode. In an episode featuring Dean Haglund (who played Langley, a member of The Lone Gunmen in the show), Haglund talks about how Carter would frequently take material from the heavily-used message boards online and then include it in the show.

Show creator Chris Carter, actress Gillian Anderson (Scully), and actor Dean Haglund (Richard Langly).

This is momentous in modern storytelling history because it’s one of the best examples of a fandom writing theories and fiction about a show, and then seeing that work included in the show itself. This is evidence for the argument that fan fiction can be so much more than the typical reputation that it gets–that it can be impactful and valuable to its source material if executed correctly.

Examples like Star Trek and The X-Files highlight ways that creators of source material can get in touch and be in tune with the desires of their respective fanbases. They perfectly illustrate how an original story stands to benefit from other creators who are in love with the source material. For Chris Carter, the fanbase was largely what drove some of the major decisions of the show. His interaction and familiarity with his audience likely contributed to the major success of the series.

Different fans execute this kind of storytelling for different series in different ways. For fans of Star Trek, it was prose about the plight of characters. For fans of X-Files, it was theories about the mythos.

And, for us, it’s The Hero of Time Project: an analytical argument for an untold story that already exists in the Zelda series, operating under rules established by the creators of the franchise, serving to expand on known characters and events while filling in the blanks which were left by those who have written these stories.

In this series of articles, we plan to outline and tell a fan-written Legend of Zelda story that has been on our minds and hearts for some time now. What makes this story special is that we had originally intended it to be a game, and wrote it to be a game. Obviously, making that game into a real, Nintendo-licensed title isn’t feasible, but the story itself has great value to us—and we think its value to the series would speak for itself, so we believe it’s time to tell it.

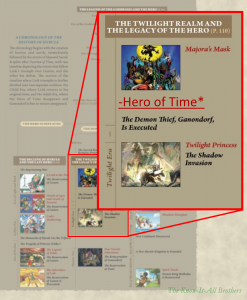

Our story will see a return to the Child Era, one of the three timelines established in the Hyrule Historia, long after the events of Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask, in the space between those two games and Twilight Princess. Our protagonist, then, will be the Hero of Time: the Link from Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask.

The Hero of Time story takes place between Majora’s Mask and Twilight Princess during the The Child Timeline.

The purpose of the Hero of Time Project is to tell our story in a way that makes clear how its themes, plot, and characters fit logically and necessarily into the rules of the series’ mythos. In this way, we hope not only to tell what we feel is an excellent story, but also to tell you:

- why it’s an important story

- what it contributes to the broader Zelda series

- what it contributes to fans of the series

- how the themes it incorporates interrelate, and make it the true missing piece of the Hero of Time’s journey.

We may even find ourselves creating a model by which to teach you, the reader, some of the related themes and rules of world-building that are integral to good storytelling.

Each of the first few articles in the Hero of Time Project will be an analysis of a particular aspect of the Legend of Zelda series—everything from establishing our story’s place in the timeline, to understanding some of the crucial elements that are part of every Zelda story, and even how the Legend of Zelda series relates to other works of literature and art—and then illustrate how our Hero of Time story aligns with these core elements of the franchise. This philosophical grounding is meant to help you, the reader, hopefully understand and enjoy the Zelda series more—and hopefully understand and enjoy our own story just as much.

When we had first started thinking about all of this, we were both beginning to get a little bored—and, frankly, worried—about the direction Zelda was taking. You can only tell the same story so many times before people lose interest in it. True, they may stay interested for decades, but how many years does this series have left? Breath of The Wild is proof that we can change the Zelda formula on a gameplay and storytelling scale without ruining the integrity of the original concept—and we believe there’s another story to be told just outside the norm of Zelda’s story structure, where storytelling meets gameplay, and the two of them meet the player.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

The Legend of Zelda is in a particularly good position to feature this kind of game because it is such a time-honored series—and, for many of us analysts at With a Terrible Fate, it is a series that’s very close to our hearts and our memories.

But what does the series really gain by inserting another story into an older and long-untouched story arc?

The answer to that is, put simply, “more than we could outline in one article.” To justify the existence of our idea and place its analytical value on display, our plan is to write out some of our ideas through the next few articles; and when the stage is set, you’re just going to have to hear the story.

We think you’ll want to hear it.

1 Comment

Jaron · October 12, 2017 at 8:23 pm

Always feel free to post questions below, and CJ and I will be happy to answer.